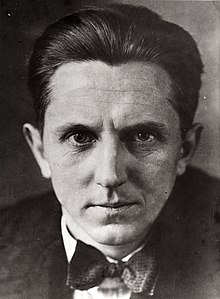

Erwin Piscator

Erwin Friedrich Max Piscator (born December 17, 1893 in Ulm , today part of Greifenstein ; † March 30, 1966 in Starnberg ) was a German theater director , director and theater pedagogue .

Piscator was an influential avant-garde of the Weimar Republic who converted the theater into a 'political tribunal' while expanding the technical possibilities on the stage . With the help of complex arrangements of film documents, image projections, moving tapes and elevators, he commented on the theatrical events and expanded the stage into an epic panorama.

The political theater developed at the Piscator theaters of the Weimar Republic achieved a broad response, but prompted contemporaries to make very contradicting assessments in view of the director's demarcation from the stage aesthetics of pure artistic beauty. Piscator's productions also had an impact on the theater theory of Bertolt Brecht , who borrowed from Piscator with his epic theater .

After many years of emigration to the Soviet Union, France and the United States, Piscator again hit the nerve of the times in the 1950s and 1960s with the staging of contemporary pieces on the Nazi past. In doing so, he initiated a phase of memory and documentary theater that led to broad social debates on questions of historical politics .

Life

Youth and World War I (1893–1918)

Piscator came from a Calvinist merchant family from Central Hesse. His parents Carl Piscator and Antonie Karoline Katharina Piscator (née Laparose), based in Marburg from 1899 , were co-owners of a textile manufacturer. Erwin Piscator's ancestors included the theologian and Bible translator Johannes Piscator , who had Latinized his family name Fischer around 1600 .

The experience of a guest performance by the Giessen City Theater in Marburg made the young Piscator decide to seek entry into the theater subject instead of the predetermined commercial career. After attending school at the Philippinum grammar school and at the municipal high school in Marburg, Piscator completed an acting training at the Otto König Theater School in Munich in autumn 1913 . After changing drama school, Piscator's new teacher Carl Graumann attested that the young drama student had a strong talent. At the same time, Piscator attended courses in art history, philosophy and German studies at the University of Munich , among others with Artur Kutscher , one of the founders of theater studies . In the 1914/15 season, Piscator also volunteered at the Royal Court and National Theater , a stage aesthetically linked to the tradition of the 19th century.

Piscator experienced the First World War , among other things, in the trench warfare in West Flanders . In the spring of 1915 he was assigned to an infantry unit on the Ypres front as a “Landsturm compulsory” and suffered severe wounds after a few months. The experience of the war shaped the pacifist and socialist convictions of Piscator, who at that time “did not feel the breath of this 'great time' in the least” ”. The disturbing poems which he published during the war years in Franz Pfemfert's literary and political weekly " Die Aktion " testify to Piscator's anti-militarist stance . From the autumn of 1917 Piscator took part in a front theater that showed a repertoire of popular entertainment pieces and whose direction he was given six months later.

Early theater work and time at the Volksbühne (1918–1927)

After the end of the war, Piscator continued his studies at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin and joined the Berlin group of Dadaism around the painters and graphic artists George Grosz and John Heartfield . After the November Revolution he joined the KPD . A first own theater project in Königsberg , in which Piscator revived nothing but “forgotten old theater exercises”, including “the transformation in the open scene and the visible Schnürboden”, failed after a few months. In Königsberg, Piscator met his first wife, the six years younger Upper Silesian actress Hildegard Jurczyk , who appeared at the New Playhouse. Erwin Piscator and Hildegard Jurczyk married in October 1919. After the failure of his first own stage in Königsberg, Piscator went back to Berlin and founded the “Proletarian Theater” there in autumn 1920.

In a staging of Alfons Paquet's play Fahnen at the Volksbühne Berlin in May 1924, Piscator made extensive use of projections and subtitles on screens and thus - as in earlier productions - anticipated central stylistic devices of " epic theater ". Paquet also called his play a “dramatic novel”, not conforming to the genre. In connection with this Piscator production, Alfred Döblin commented in the Leipziger Tageblatt that the author of the play was "epic, not lyrically inflamed" and that the form of the novel drama influenced by Paquet could again become the "top soil of the drama". In the debate that arose a few years later about the authorship of the term and the methodology of epic theater, Döblin's observations of 1924 played an important role.

Following the successful flag production, Piscator was permanently committed to the Volksbühne on Bülowplatz as senior director in 1924 . The Volksbühne Berlin was a visitor organization with a large number of members, whose aim was to give Berlin workers access to civic education under the guiding principle “The art of the people”. The declared intention of the Volksbühne artistic director and Piscator discoverer Fritz Holl , who was only recently introduced into his office, was to pave the way for "young drama that reflected the movements of the time". In addition to his new role as head director at the Volksbühne, Piscator staged satirical evenings, choruses and political reviews on behalf of the KPD, in which he first tried out the use of cinematic means.

A guest production that Piscator carried out at the Prussian State Theater in 1926 under the direction of Leopold Jessner , Friedrich Schiller's play Die Räuber, caused a considerable stir . Against the pathetic exaggeration of Schiller's poetry, which has been increasingly cultivated on German stages since the March Revolution of 1848 , Piscator set a radical review and updating of his original. In front of a simultaneous multi-storey stage, the gang's internal opponent of the count's son Karl Moor, Moritz Spiegelberg, in a Trotsky mask, was staged as a “Bolshevik intellectual revolutionary”. The "Schiller villain" Spiegelberg "advanced to become a hero who does not allow himself to be seduced by personal feelings or ambition."

Although various classic productions of the Weimar Republic, such as Erich Ziegel's Hamburg Robber production from 1921, had updated elements such as robbers in contemporary costumes and militarily organized robbers, the response to the rapid Piscator production clearly exceeded previous controversies both in sharpness and in the contradiction in assessments . While the Austrian journalist and satirist Karl Kraus wanted to ironically refer to Schiller's drama as "Piscator dramas" from now on, the debate in the German feuilletons was through exaggeration and suggestive terms such as "Klassikerschlaf" ( Bernhard Diebold ) or "Klassikertod" ( Herbert Ihering ) embossed.

In 1927, after a decline in membership at the Volksbühne due to inflation and due to fears on the part of the Volksbühne board that Piscator's work would endanger the non-partisan orientation of the visitor organization, a rift broke out. Decisive for the scandal was a contemporary references auslotende production of Ehm Welk's drama thunderstorm over Gottland in which the famous actor Heinrich George the Claus Störtebecker played. The board accused Piscator of having subjected the play to a tendentious-political reinterpretation and a provocative portrayal of “social revolution”.

The Piscator stages (1927–1931)

After this scandal, Piscator opened his own theater in 1927, the Piscator stage , in a 1,100-seat theater building on Nollendorfplatz . In his application for the stage license, he claimed a group of “16 individual actors, 1 dramaturge, 8 technical and 5 commercial employees” as staffing. Piscator was able to win over the Berlin industrialist Ludwig Katzenellenbogen to finance the undertaking .

Piscator's staging of contemporary plays and novel adaptations such as Ernst Toller's Oops, we're alive! (1927) or The Adventures of the Good Soldier Schwejk according to Jaroslav Hašek (1928) impressed the audience with their elaborate stage equipment, which was trained on constructivist principles. They established Piscator's reputation as an unprecedented stage aesthetic innovator and earned him the recognition of 'the only capable playwright besides me' by Bertolt Brecht .

Piscator's first directorial work on his own stage, Ernst Toller's Oops, we're alive! about a former revolutionary from 1918 who, after his release from eight years of imprisonment, breaks with the pragmatic changes in attitudes of former comrades-in-arms, showed Piscator's virtuoso design of the stage action through complex media arrangements in 1927. The film, sound and scenery effects of the production included a four-story stage for the numerous short scenes in the offices of the ministries or the various hotel rooms of the third act. Film scenes or illustrations were projected onto a screen in the middle of the stage. The first act began with a documentary film about the world historical events of the years that the main character spent in prison. A title song by Walter Mehring set to music by Edmund Meisel gave an ironic commentary on the plot. The theater critic Herbert Ihering judged: "A phenomenal technical imagination has created miracles."

According to Piscator, the use of complex technical elements such as film and image projections, moving tapes, metal constructions or elevators happened with a dramaturgical, not illusionistic intention. Piscator's daring arrangements and his stage technical means should support political and economic analyzes in the sense of the proclaimed party-taking, "political theater".

Bertolt Brecht , Egon Erwin Kisch , Leo Lania , Moshe Lifshits , Heinrich Mann , Walter Mehring and Erich Mühsam belonged to the extensive dramaturgical collective of the Piscator stage . George Grosz , John Heartfield and László Moholy-Nagy worked as set designers on the Piscator stage , Curt Oertel and Svend Noldan as film producers and fitters and Edmund Meisel and Franz Osborn as musicians . Hanns Eisler wrote his first incidental music in 1928 for Piscator. Many well-known actors appeared on the Piscator stage: Sybille Binder , Tilla Durieux , Ernst Deutsch , Paul Graetz , Alexander Granach , Max Pallenberg , Paul Wegener , Hans Heinrich von Twardowski and others.

In view of the extraordinarily elaborate and costly productions, however, a bankruptcy petition by the Berlin tax authorities forced the temporary closure of the Piscator stage as early as 1928. Two reopenings in the two following years did not lead to the long-term consolidation that had been hoped for. In the year of the Great Depression, 1929, Piscator's programmatic work Daspolitische Theater was published , which vividly reviewed the more important productions of the theater director and unfolded his view of the theater as a decisive means "in the beginning process of intellectual revolution". The first of numerous translations was a translation into Spanish (El teatro político) in 1930 , into Japanese (Sayoku Gekij) in 1931 and into Ukrainian (Politytschnyj teatr) in 1932 .

Projects abroad, emigration and return (1931–1962)

After liquidity problems, Piscator went to the Soviet Union in 1931 and produced his only feature and sound film Der Aufstand der Fischer (1934) based on a novella by Anna Seghers in the Arctic port city of Murmansk and on the Ukrainian Black Sea coast near Odessa . The film deals with the resistance of striking sailors to the inhumane working conditions on the ships of the shipowner Bredel. One of the key scenes of the film is the funeral of the strike leader Kedennek, who was killed by the military who rushed to the scene, which ends in a fiasco. The funeral of Kedennek becomes a beacon, and an uprising by coastal fishermen across the region begins. Piscator caused a stir by using a moving camera, which Sergej Eisenstein criticized and rejected.

But Piscator was spied on by the Soviet secret police GPU from the start . German communists who lived in exile in Moscow also denounced him as "politically unreliable".

During a theater conference in Moscow in 1935, which was chaired by Piscator as chairman of an international theater association, the British theater reformer Edward Gordon Craig conveyed to him in the Hotel Metropol advances from Propaganda Minister Goebbels to return to Berlin and to resume his work there. In 1936 the director, sobered by his experience of Stalinism, emigrated to France from the Soviet Union after denunciations as a Trotskyist and an apparently xenophobic attack .

After the beginning of the Spanish Civil War , in 1936, at the invitation of the democratically elected republican government in Catalonia, he called for the defense of democracy and the fight against the putschists. Referring to his experience as director of a front-line theater during the First World War, he called for the arts to contribute to the defense of democratic culture in Catalonia and Spain, “bringing works of the small form to the front” and “satirical groups” . However, Piscator itself did not carry out its own productions on site.

During the years of deprivation of emigration, there was another important meeting that led to a second marriage in 1937. Piscator's first marriage to actress Hildegard Jurczyk, which had existed since 1919, was dissolved by mutual agreement in Berlin around 1930. In Salzburg , Piscator, who came from the Soviet Union, met the educated and wealthy dancer Maria Ley from Max Reinhardt . Ley had written a dissertation on Victor Hugo at the Sorbonne in 1934 . “Only recently had she lost her husband Franz Deutsch, son of one of the directors of the Berlin AEG , and now she and Piscator wanted to get married. Brecht was supposed to be one of the best man. From the beginning of 1937, when he moved to her house in Neuilly , until his return to Germany in 1951, she was a loyal partner to Piscator in all of his endeavors. ”In France, in 1938, Piscator developed an elaborate stage adaptation of Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy's historical novel War and Peace , which he hoped to accommodate in London's West End and on New York's Broadway with the support of US theater producer Gilbert Miller .

After he emigrated to the United States a few months before the start of World War II , these plans came to nothing. Instead, between 1940 and 1951, Piscator was the founder and director of a drama school, the Dramatic Workshop at the New School for Social Research in New York (it was replaced by the New School in 1949). The “New School” provided employment opportunities for numerous prominent refugees from Europe during the Second World War. In 1947/48 the Dramatic Workshop with almost a thousand students, about a third of whom were taking full-time courses, had reached the limit of capacity. The workshop staff included Stella Adler , Herbert Berghof , Lee Strasberg , Kurt Pinthus , Hans José Rehfisch , Carl Zuckmayer , Hanns Eisler , Erich Leinsdorf and Jascha Horenstein . Piscator's US students at the workshop included Beatrice Arthur , Harry Belafonte , Marlon Brando , Tony Curtis , Jack Garfein , Judith Malina , Walter Matthau , Rod Steiger , Elaine Stritch, and playwright Tennessee Williams .

Following extensive preliminary investigations by the FBI into a deportation process against Piscator, the emigrant received a summons from the Committee on Un-American Activities at the height of the McCarthy era in 1951 . Under the impression of aggressive press reports, which had defamed the Dramatic Workshop as an organization of communist "fellow travelers" , and the summons from the committee, Piscator suddenly returned to Germany.

After an absence of more than twenty years from Germany, he was initially forced to work as a guest director on numerous stages in the Federal Republic and other Western European countries. Plans to found a theater academy in cooperation with the rector of the University of Frankfurt Max Horkheimer were unsuccessful in 1953. A first step towards a comeback was the acceptance of Piscator's stage version of Lev Tolstoy's War and Peace at the Schillertheater in West Berlin in 1955 , a production with an unprecedented success with the public, but with a devastating press response.

In the 1950s Piscator received several honors, including the Goethe plaque from the State of Hesse in 1953 . On the occasion of his 65th birthday, he was awarded the Federal Cross of Merit in 1958 .

Artistic director at the Freie Volksbühne (1962–1966)

In 1962 Piscator came to the Freie Volksbühne in West Berlin as artistic director , which he led as successor to Günter Skopnik until his death. In 1963 they moved from the theater on Kurfürstendamm , which had been used as a performance venue until then, to the Freie Volksbühne's own theater .

Piscator's central concern in his late stagings was the confrontation with the “general desire to forget” and the deficit German culture of remembrance in view of the Holocaust .

This program orientation was effectively reflected in his productions of the world premieres of Rolf Hochhuth's "Christian tragedy" Der Stellvertreter (world premiere on February 20, 1963) and Peter Weiss ' minimalist play on the Auschwitz trial The Investigation (Ring world premiere on October 19, 1965) . With widely divergent documentary approaches, both theater texts raised the political-moral question of responsibility, guilt and awareness of injustice of the individual in the dictatorship and led to wide-ranging historical - political disputes throughout Germany and internationally .

Piscator's third directorial work at the Freie Volksbühne, Rolf Hochhuth's The Deputy , became a sensational stage event. The theater critic Henning Rischbieter summed up: The deputy shows the ability of the theater to “produce direct political effects. Contrary to all (justified) aesthetic objections, it triggered an excited discussion through its questioning and the passionate accusation that the author uttered through its main character, influenced the reform movement within the Catholic Church and made contemporary historiography to deal with a previously neglected, even taboo Subject required: How did the Catholic Church and its then head, Pope Pius XII. , behave towards the National Socialist mass murder of European Jews? "

A whole year passed between the first contact with the text, which Piscator had in the spring of 1962, and the staging. Piscator's staging, carefully prepared in advance, meant that the feared scandal - at least in Berlin - did not materialize. Internationally, Der Stellvertreter nevertheless provoked “passionate journalistic disputes, public mass demonstrations, parliamentary debates, foreign policy upsets and diplomatic interventions.” The director of the Berlin premiere cut the text by half, reduced the number of actors to half and the storylines of the thematically complex one Works entirely on Pope Pius XII. and his behavior in relation to the Holocaust focused. The Berlin commentators praised the play as one of the most important and exciting events in German-language theater in recent years.

For the “Auschwitz Oratorio” The Investigation of Peter Weiss, Piscator agreed with the Suhrkamp-Theaterverlag a ring premiere on October 19, 1965, in which fourteen West and East German theaters and the Royal Shakespeare Company in London took part. The play dealt with the first Frankfurt Auschwitz trial from 1963 to 1965 using the means of documentary theater. In the West Berlin production, which was the focus of nationwide attention and for which the Italian composer Luigi Nono had created stage music, Piscator let the audience look at the process and the accused from the perspective of the survivors. Following the Ring premiere, the play initially found its way into the repertoire of theaters in Amsterdam, Moscow, New York, Prague, Stockholm and Warsaw from 1965 to 1967.

With his last production, Piscator could not build on the successes of the premiere of the previous years. The revolt of the officers, based on a novel by Hans Hellmut Kirst , premiered on March 2, 1966, but the author had not mastered his material dramaturgically. The actors Ernst Deutsch and Wolfgang Neuss had left rehearsals prematurely, and the press reacted with devastating reactions. Piscator was still ill during the rehearsals and then went to a sanatorium on Lake Starnberg to relax . After an emergency operation on his inflammatory gall bladder , Piscator died on March 30, 1966 in Starnberg.

Piscator's grave of honor is located in the Zehlendorf forest cemetery in Dept. XX-W-688/690.

Theatrical significance

Program and impulses

Numerous technical innovations on the stage go back to Piscator's theater practice in the Weimar Republic since 1925, including the extensive use of commenting image and text projections, the recording of film documents as a "living backdrop" on gauze veils or screens, and the use of elaborate scaffolding structures ( simultaneous stages in combination with a revolving stage, Treadmills, escalators or elevator bridges), which Piscator had implemented by his experimental stage architect Traugott Müller . Müller's maxim: "I've been working on getting rid of the stage design for years."

With the development of the political revue , Piscator exercised significant influence on the political mass theater of the Weimar Republic. By organizing his texts according to the principle of maximum contrasts and unexpected arrangements, he achieved sharp political-satirical effects and anticipated the forms of commentary in epic theater. He distinguished himself from the epic theater of Brecht by his directorial approach that integrates the viewer into the scene. With Piscator, the shock and the activation of the audience should go hand in hand:

- For lack of imagination, most people do not even experience their own life, let alone their world. Otherwise reading a single newspaper would have to be enough to upset humanity. So stronger resources are needed. One of them is the theater.

In 1927, together with Walter Gropius , the founder of the avant-garde art school Bauhaus , Piscator designed the project of a “ total theater”, the abolition of the spatial separation between actors and actresses , in order to be able to constructively realize his immersive theater concept that challenges the audience to actively participate in the stage action Spectators and the replacement of the depth and peep box stage was the order of the day. In view of the unsuccessful search for a potent financial sponsor for the monumental total theater project, the intended direct identity of stage and audience remained an unfinished theater vision of Piscator. Through his work as a director on small New York repertoire stages founded especially for the Dramatic Workshop (Studio Theater, President Theater, Rooftop Theater) and as a theater pedagogue in US exile, Piscator later influenced the "rise and recognition of ' Off-Broadway '" and the American experimental theater (such as the Living Theater ), founded by his student and assistant Judith Malina , who also published The Piscator Notebook about the work during this period.

Piscator was directed against traditional notions of the hermetic and unchangeable work of art itself. In his stagings, the normative autonomous stage aesthetics that had shaped the staging practice of German theaters at the beginning of the 20th century were overcome. Piscator's theater conception was attempted to fit into the larger frame of reference of an anti-idealistic material aesthetic. The theater and literary scholar Werner Mittenzwei described their followers as pioneers of a profound change in the function of art in contrast to the autonomous aesthetics of pure artistic beauty. The “material aesthetes” of the late Weimar Republic understood older artistic materials as changeable material that could be adapted to current challenges. They reworked conventional templates with the intention of working towards a fundamental reshaping of social structures, or they worked out anew. They aimed for new forms of reception and wanted to activate the viewer and upgrade them as co-producers. The societal informative value of the work of art should have priority over its purely aesthetic experience value.

The programmatic of material aesthetics was also reflected in Piscator's practice of staging novels (by Jaroslav Hašek , Theodore Dreiser , Theodor Plievier , Robert Penn Warren and others) and historical material. Piscator's stage version of Lev Tolstoy's historical novel War and Peace , which has been revised several times , has been translated into several languages since 1955 and performed in 16 countries. In the Federal Republic of Germany, Piscator's interventionist theater experienced a late second bloom. He became an initiator and source of inspiration with the staging of world premieres, which were characterized by a commitment to coming to terms with the Nazi past (Hochhuth, Weiss) and criticism of nuclear armament ( Heinar Kipphardts In der Fall J. Robert Oppenheimer , 1964) for the memory and documentary theater .

Influences and fellow campaigners

The time of the Weimar Republic was one of the most creative and experimental epochs in German history. Piscator moved in an environment characterized by the search for new theater approaches, the amalgamation of different forms of art and perception ( synaesthesia ) and lively artistic-political debates. Piscator's punctual correspondences with regard to individual aspects such as the political intention to have an effect, the extensive use of the stage machinery or the target audience existed with the theater approaches of various German-speaking colleagues.

The Austrian theater entrepreneur Max Reinhardt , who played the Great Playhouse in Berlin with 5000 seats and was considered the antipode of Piscators, impressed a mass audience with similar spacious arrangements in front of a panoramic horizon and with the extensive use of the stage machinery, with play on an arena stage and a huge revolving stage . The former stage expressionist Leopold Jessner was also considered to be a representative of an, albeit more moderate, “political theater” of the Weimar Republic. As director of the Prussian State Theater, Jessner emerged with productions such as Schiller's Wilhelm Tell , in which he made a reductionist stage stage the background of a passionate symbolic commitment to the young republic. Smaller stages like Karlheinz Martins “Tribüne” wanted to open up new cultural spheres to a proletarian audience in the wake of Expressionism - similar to the first stages of the early Piscator.

In many cases, there were similarities between Piscator and Russian theater and film directors with regard to the use of film on the stage and photographic montage at Eisenstein , the Segment Globus stage at Meyerhold, or the confrontation between actor and puppet at Mayakovsky (as well as the British Edward Gordon Craig). An on-site encounter with the work of the Soviet theater avant-garde in connection with Piscator's first trip to the Soviet Union did not take place until September 1930. The ideas laid out in the work of colleagues were often found in condensed form at Piscator, either by developing them at the same time or by integrating and repurposing them as external inspiration in his theater concept.

The direct contributions of numerous employees to his productions are more demonstrable than the indirect influences of other avant-garde theater practitioners of his time on Piscator. In keeping with Piscator's understanding of staging as a collective work process, the productions on the Piscator stage were the result of a politically-aesthetically motivated community effort under the direction of the director as primus inter pares . The dramaturge was already replaced by a larger one on the Piscator stage "Dramaturgical collective": "A whole team of writers should oversee the literary program and examine the individual texts of the plays."

The collective headed by Felix Gasbarra and Leo Lania included Walter Mehring, Bertolt Brecht, Erich Mühsam, Moshe Lifshits, Franz Jung and Alfred Wolfenstein as employees . Alfred Döblin, Kurt Tucholsky , Johannes R. Becher and the film critic Béla Balázs were brought in on a case-by-case basis. In addition to the group of dramaturgical experts, changing set designers, costume designers, choreographers, composers and actors contributed to the success of the Piscator stage. In extreme cases, it was possible that a single person spent himself in changing functions as author, dramaturge, reader and leading actor (as happened in the case of Theodor Plievier with Des Kaisers Kulis in 1930 at the Lessing Theater). The fruitfulness of the collaborative mode of production was still evident in Piscator's late works, in which the close cooperation with authors such as Rolf Hochhuth or Peter Weiss , stage sets such as Hans-Ulrich Schmückle or composers such as Boris Blacher and Luigi Nono occasionally took on forms that were as intense as in the twenties Years.

Cultural activities and reminiscences

As a theater-maker for whom aesthetic form and political aspirations basically coincided, Piscator also undertook numerous initiatives in the field of cultural promotion and theater education throughout his life (member of the writers' association " Gruppe 1925 ", co-founder of the "Volksverband für Filmkunst", establishment of the "studio" at the Piscator stage, conception of a "German State Theater" in Engels etc.). He was co-initiator and president of the German Academy of Performing Arts founded in Hamburg in 1956 , President of the Berlin State Association of the German Stage Association , member of the Performing Arts department of the Academy of Arts Berlin (West), corresponding member of the German Academy of Arts Berlin (East) and since 1959 member of the PEN Center of the Federal Republic .

At the suggestion of his second wife Maria Ley , the "Erwin Piscator Award" has been given annually in New York since 1986 to prominent theater and film-makers as well as other artists (so far to Giorgio Strehler , Robert Wilson and Peter Zadek, among others ). The organizer is the non-profit organization "Elysium - Between Two Continents". In addition to the German-American Acting Prize, venues in several countries are a reminder of Piscator's importance for European theater, including the Marburg City Hall, which opened in 1969 as the "Erwin-Piscator-Haus", and the Teatro Erwin Piscator, founded in 1972 in the southern Italian city of Catania , a sculpture inaugurated in 1980 by the Scottish sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi north of central London as well as several memorial plaques in Berlin, among others. On the occasion of the 100th birthday in 1993, a state road in Piscator's birthplace Ulm (Greifenstein) was named after the director. A memorial was erected there in the 50th year of his death.

The archive of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin (since 1966/1971) and the Southern Illinois University Carbondale (since 1971) keep extensive documents on Piscator's life and work . The whereabouts of the originals of the extensive Piscator diaries from the 1950s and 1960s is still unclear.

Productions

- 1924: Alfons Paquet , flags ( Volksbühne Berlin , May 26, 1924)

- 1924: Revue Roter Rummel (Berlin Halls, November 22, 1924)

- 1925: In spite of all that! Historical revue ( Großes Schauspielhaus Berlin, July 12, 1925)

- 1926: Alfons Paquet, storm surge (Volksbühne, February 20, 1926)

- 1926: Friedrich Schiller , The Robbers ( Prussian State Theater Berlin , September 11, 1926)

- 1927: Ehm Welk , thunderstorm over Gottland (Volksbühne, March 23, 1927)

- 1927: Ernst Toller , oops, we're alive! ( Piscator stage Berlin, September 3, 1927)

- 1927: Alexei Nikolajewitsch Tolstoy and Pavel Schtschegolew, Rasputin, the Romanovs, the war and the people who rose up against them (Piscator stage, November 12, 1927)

- 1928: Max Brod and Hans Reimann , The Adventures of the Good Soldier Schwejk (Piscator stage, 23 January 1928)

- 1928: Leo Lania, Konjektiven (Piscator stage in the Lessing Theater (Berlin) , April 8, 1928)

- 1929: Walter Mehring , The Merchant of Berlin (Second Piscator Stage, September 6, 1929)

- 1952: Gotthold Ephraim Lessing , Nathan the Wise ( Schauspielhaus Marburg , May 14, 1952)

- 1954: Arthur Miller , witch hunt ( Nationaltheater Mannheim , September 20, 1954)

- 1955: Lev Tolstoy , War and Peace ( Schillertheater Berlin, March 20, 1955)

- 1957: Friedrich Schiller, The Robbers (Nationaltheater Mannheim, January 13, 1957)

- 1962: Bertolt Brecht , Refugee Talks ( Münchner Kammerspiele , world premiere, February 15, 1962)

- 1962: Gerhart Hauptmann , Atriden-Tetralogie ( Theater am Kurfürstendamm , October 7, 1962, shortened adaptation by Erwin Piscator)

- 1963: Rolf Hochhuth , The Deputy (Theater am Kurfürstendamm, February 20, 1963)

- 1963: Romain Rolland Robespierre ( Freie Volksbühne Berlin , May 1, 1963, stage adaptation by Erwin Piscator and Felix Gasbarra)

- 1964: Heinar Kipphardt , In the case of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Freie Volksbühne Berlin, October 11, 1964)

- 1965: Peter Weiss , The Investigation (Freie Volksbühne Berlin, October 19, 1965)

Film, television, radio play

Feature and television films

- The uprising of the fishermen after Anna Seghers (USSR: Meschrabpom 1934).

- In the gear train according to Jean-Paul Sartre ( HR , 1956)

Radio plays

- Returning from Ilse Langner ( NWDR , 1953)

- Gas by Georg Kaiser ( HR , 1958)

- Göttingen cantata by Günther Weisenborn ( SDR , 1958)

- Rolf Hochhuth's deputy (HR, 1963)

TV documentaries about Piscator

- A man named Pis . Screenplay & Director: Rosa von Praunheim . 1991.

- Portrait of the famous theater director Erwin Piscator . Screenplay: Ulf Kalkreuth. ORB, Potsdam 1993.

- The revolutionary - Erwin Piscator on the world stage . Director: Barbara Frankenstein, Rainer KG Ott . SFB, Berlin 1988.

- Weltbühne Berlin - the twenties . Screenplay: Irmgard vz Mühlen. Chronos, Berlin 1991 (short original recording by Piscator 1927).

literature

Fonts

- Erwin Piscator: Letters. Volume 1: Berlin - Moscow 1909–1936 . Edited by Peter Diezel. B&S Siebenhaar, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-936962-14-6 .

- Erwin Piscator: Letters. Volume 2: Paris, New York 1936–1951. Edited by Peter Diezel. B&S Siebenhaar, Berlin 2009.

- Volume 2.1: Paris 1936–1938 / 39. ISBN 978-3-936962-57-4 .

- Volume 2.2: New York 1939-1945. ISBN 978-3-936962-58-1 .

- Volume 2.3: New York 1945–1951. ISBN 978-3-936962-70-3 .

- Erwin Piscator: Letters. Volume 3 edited by Peter Diezel. B&S Siebenhaar, Berlin 2011.

- Volume 3.1: Federal Republic of Germany, 1951–1954. ISBN 978-3-936962-83-3 .

- Volume 3.2: Federal Republic of Germany, 1955–1959. ISBN 978-3-936962-84-0 .

- Volume 3.3: Federal Republic of Germany, 1960–1966. ISBN 978-3-936962-85-7 .

- Erwin Piscator: The Political Theater . Revised by Felix Gasbarra, with a foreword by Wolfgang Drews. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1963, DNB 453784836 . (Original edition: Adalbert Schultz, Berlin 1929, DNB 575381558 )

- Erwin Piscator: theater, film, politics. Selected writings . Edited by Ludwig Hoffmann. Henschel, Berlin 1980, DNB 800345460 .

- Erwin Piscator: Zeittheater. The political theater and other writings. 1915-1966. Selected and edited by Manfred Brauneck and Peter Stertz. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1986, ISBN 3-499-55429-1 .

- War and peace . Based on the novel by Leo Tolstoy, retold and edited for the stage by Alfred Neumann , Erwin Piscator and Guntram Prüfer. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1955, DNB 453564526 .

Secondary literature

- Ullrich Amlung (Ed.): "Life - is always a beginning!" Erwin Piscator 1893–1966. The director of political theater . Jonas, Marburg 1993, ISBN 3-89445-162-9 .

- Knut Boeser, Renata Vatková (Eds.): Erwin Piscator . A working biography in 2 volumes (= Series German Past , Volume 11). Frölich and Kaufmann / Edition Hentrich, Berlin 1986.

- Volume 1: Berlin 1916-1931. ISBN 3-88725-215-2

- Volume 2: Moscow-Paris-New York-Berlin 1931–1966. ISBN 3-88725-229-2 .

- Franz-Josef Deiters : "'the theater [...] placed at the service of the revolutionary movement'. Erwin Piscator's model of an agitation and propaganda theater". In: Franz-Josef Deiters: Secularization of the Stage? On the mediology of the modern theater. Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag, 2019. ISBN 978-3-503-18813-0 , pp. 103-131.

- Heinrich Goertz : Erwin Piscator in self-testimonies and image documents. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1974, ISBN 978-3-499-50221-7 (previously: ISBN 3-499-50221-6 )

- Hermann Haarmann : Erwin Piscator and the fate of the Berlin dramaturgy. Supplements to a chapter of German theater history . Wilhelm Fink, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-7705-2685-6 .

- Peter Jung: Erwin Piscator. The political theater. A comment . Nora, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-86557-105-2 .

- Judith Malina : The Piscator Notebook . Routledge Chapman & Hall, London 2012, ISBN 978-0-415-60073-6 .

- Klaus Wannemacher: Erwin Piscators Theater against Silence: political theater between the fronts of the Cold War (1951–1966) (= Theatron , Volume 42), Niemeyer, Tübingen 2004, ISBN 978-3-484-66042-7 (dissertation University of Heidelberg 2002, VIII, 287 pages, illustrations; under the title Piscator and the unresolved past ).

- Klaus Wannemacher: Meeting the amnesia of the audience. Post-war theater as an incubator of the "coming to terms" discourse. In: Stephan A. Glienke, Volker Paulmann and Joachim Perels (eds.): Success story Federal Republic? Post-war society in the long shadow of National Socialism. Wallstein, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8353-0249-5 , pp. 263-291.

- Carl ways: Piscator, Erwin Friedrich Max. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 20, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-428-00201-6 , pp. 478-480 ( digitized version ).

- John Willett : Erwin Piscator. The opening of the political age on the theater . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-518-10924-3 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Erwin Piscator in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Erwin Piscator in the German Digital Library

- Search for Erwin Piscator in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Kornelia Papp / Janca Imwolde: Erwin Piscator. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- erwin-piscator.de , website about Piscator including the "Annotated Erwin Piscator Bibliography" with over 1300 title entries

- Erwin-Piscator-Center in the archive of the Academy of Arts, Berlin

- Erwin Piscator Papers from the Morris Library, Southern Illinois University , inventory overview

- Film sequences of the Piscator productions 1927–29 (filmportal.de)

- Elysium Between Two Continents , founder of the Erwin Piscator Award

- Erwin Piscator on arts in exile

Individual evidence

- ↑ Martina Thöne: Between Utopia and Reality. The dramatic work of Alfons Paquet. Peter Lang, Frankfurt a. M. u. a. 2005, p. 318.

- ↑ Heinrich Goertz: Erwin Piscator in personal testimonials and image documents. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1974, ISBN 3-499-50221-6 , p. 140. - In contrast, Walther Baumann: The Herborner and the Strasbourg fishermen. Piscator. In: Bulletin of the Herborn History Association, 26th year (April 1978), No. 2, pp. 23-30.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Grell: Erwin Piscator 1893-1966. Stations in his life - key words on work and effect . In: “Life - is always a beginning!” Erwin Piscator 1893–1966. The director of political theater . Edited by Ullrich Amlung in collaboration with the Akademie der Künste, Berlin. Jonas, Marburg 1993, p. 13.

- ^ Letter from Erwin Piscator to Antonie and Carl Piscator, April 24, 1914, In: Erwin Piscator. The letters. Volume 1: Berlin - Moscow (1909–1936). Edited by Peter Diezel. Bostelmann and Siebenhaar, Berlin 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Artur Kutscher: The theater professor. A life for the science of the theater. Ehrenwirth, Munich 1960, p. 83.

- ^ Letter from Erwin Piscator to Antonie and Carl Piscator, 16.II.1917, in: Erwin Piscator. The letters. Volume 1. Edited by Peter Diezel. Berlin 2005, p. 74.

- ↑ See the reprint in: Erwin Piscator. Time theater. "The political theater" and other writings from 1915–1966 . Selected and edited by Manfred Brauneck and Peter Stertz. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986, pp. 449-454.

- ^ Wolfgang Petzet: Theater. The Münchner Kammerspiele 1911–1972 . Munich 1973, p. 136f.

- ↑ Paquet was involved in the 18th century genre of the "dramatic novel" (dialogue novel) and Lion Feuchtwanger's drama Thomas Wendt. A dramatic novel (1919) oriented.

- ^ Alfred Döblin in: Leipziger Tagblatt, No. 145, June 11, 1924, quoted from: Erwin Piscator: Das Politische Theater . Adalbert Schultz, Berlin 1929, p. 58. See Peter Jung: Erwin Piscator. The political theater. A comment. Nora, Berlin 2007, p. 116 f.

- ↑ Peter Jung: Erwin Piscator. The political theater. A comment. Berlin 2007, p. 109.

- ↑ Peter Jung: Erwin Piscator. The political theater. A comment. Berlin 2007, p. 162.

- ↑ Peter Jung: Erwin Piscator. The political theater. A comment. Berlin 2007, p. 165.

- ^ Karl Kraus: Accountability report . In: Die Fackel , Heft 795–799, pp. 1–51. Quoted from: Karl Kraus: Before the Walpurgis Night . Volk und Welt, Berlin 1971, p. 355.

- ↑ See Herbert Ihering: Reinhardt, Jessner, Piscator or Klassikertod? Ernst Rowohlt, Berlin 1929. - Cf. Erwin Piscator: Das Politische Theater . Adalbert Schultz, Berlin 1929, pp. 85-91.

- ↑ Piscator later staged Schiller's play Die Räuber twice more (Nationaltheater Mannheim, January 13, 1957 and Städtische Bühnen Essen, February 24, 1959)

- ↑ Peter Jung: Erwin Piscator. The political theater. A comment. Berlin 2007, pp. 203f.

- ↑ Bertolt Brecht. Writings 2. 1933–1942 . Berlin and Weimar, Frankfurt 1993 (Bertolt Brecht. Works. Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt editions. Vol. 22.2). P. 763.

- ↑ Herbert Ihering: “Oops, we're alive!” Piscator stage . In: Berliner Börsen-Courier, No. 414, September 5, 1927, quoted from: Herbert Ihering. Theater in action. Reviews from three decades. 1919-1931 . Edith Krull and Hugo Fetting. Argon, Berlin 1987, pp. 282-285, here p. 284.

- ↑ John Willett: Erwin Piscator. The opening of the political age on the theater . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 1982, pp. 69-73, here: p. 70.

- ↑ On the concept of "political theater" see: Peter Langemeyer: "Politisches Theater": attempt to define an unexplained term - following Erwin Piscator's theory of political theater . In: Aspects of political theater and drama from Calderón to Georg Seidel: Franco-German perspectives . Edited by Horst Turk and Jean-Marie Valentin in conjunction with Peter Langemeyer. Bern, Berlin a. a. 1996, pp. 9-46.

- ^ Letter from Erwin Piscator to Lasar M. Kaganowitsch , December 15, 1932, in: Erwin Piscator. The letters. Volume 1. Edited by Peter Diezel. Berlin 2005, p. 246.

- ↑ In more detail: Jeanpaul Goergen: Wosstanije rybakow ("Uprising of the Fishermen"). USSR, 1934. A film by Erwin Piscator. A documentation . Berlin 1993; Hermann Haarmann (Ed.): Erwin Piscator on the Black Sea. Letters, memories, photos . Bostelmann & Siebenhaar, Berlin 2002; Rainhard May, Hendrik Jackson (ed.): Films for the Popular Front. Erwin Piscator, Gustav von Wangenheim, Friedrich Wolf - anti-fascist filmmakers in exile in the Soviet Union . Berlin 2001.

- ↑ Klaus Gleber: theater and public. Production and reception conditions of political theater using the example of Piscator 1920–1966. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1979, pp. 302, 539.

- ↑ Erwin Piscator's theater work in Russia in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , August 22, 2018, p. 12.

- ↑ During a New Year's Eve party in the early morning hours of January 1, 1936 in the Moscow Hotel Metropol, Piscator was knocked down by several Russian guests after a dispute. Piscator then complained of "such riots against foreigners", since witnesses to the incident had testified that "these foreigners are not needed at all". See Julia I. Annenkowa's letters to Wilhelm Pieck , September 8, 1936, and Erwin Piscator to Genrich G. Jagoda , January 4, 1936. In: Peter Diezel (Ed.): Erwin Piscator. The letters. Volume 1. B&S Siebenhaar, Berlin 2005, p. 409 f. and p. 466.

- ↑ Erwin Piscator. Theater, film, politics . Selected Writings. Edited by Ludwig Hoffmann. Henschel, Berlin 1980, pp. 163–168, here: p. 164.

- ↑ John Willett: Erwin Piscator. The opening of the political age on the theater . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 1982, p. 102; See also the two volumes: Maria Ley-Piscator: The dance in the mirror. My life with Erwin Piscator . Reinbek 1993; Erwin Piscator. Letters from Germany. 1951-66. To Maria Ley-Piscator . Edited by Henry Marx, with collaboration from Richard Weber. Prometh, Cologne 1983.

- ↑ Alexander Stephan : In the sights of the FBI. German writers in exile in the files of the American secret services . Stuttgart / Weimar 1995, p. 373.

- ↑ Klaus Gleber: theater and public. Frankfurt am Main 1979, p. 371.

- ↑ Erwin Piscator. A working biography in 2 volumes. Volume 2: Moscow - Paris - New York - Berlin . Edited by Knut Boeser, Renata Vatková. Edition Hentrich, Berlin 1986, p. 198.

- ^ Foreword by Erwin Piscator. In: Rolf Hochhuth: The Deputy . Reinbek 1963, p. 8.

- ↑ Henning Rischbieter (ed.): Through the iron curtain. Theater in divided Germany from 1945 to 1990 . Edited in collaboration with the Akademie der Künste. Propylaea, Berlin 1999, p. 139.

- ↑ Peter Reichel: Invented memory. World War I and the murder of Jews in film and theater . Carl Hanser, Munich / Vienna 2004, pp. 217–227, here p. 222.

- ↑ To this more detailed Matthias Kontarsky: Trauma Auschwitz. On the processing of what cannot be processed at Peter Weiss, Luigi Nono and Paul Dessau . Pfau, Saarbrücken 2002; Matteo Nanni: Auschwitz - Adorno and Nono. Philosophical and music-analytical investigations . Rombach, Freiburg 2004.

- ↑ Jochen Vogt: Peter Weiss . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1987, p. 95 (Rowohlt's monographs, 376).

- ↑ Heinrich Goertz: Erwin Piscator in personal testimonials and image documents. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1974, ISBN 3-499-50221-6 , p. 132 f.

- ↑ Piscator had already developed the plans for the development of new forms of theater “with the participation of the cinema” and new lighting effects as early as 1920. See Erwin Piscator's letter to George Grosz, May 1920, In: Thomas Tode: We blow up the peep box stage! Erwin Piscator and the film. In: Michael Schwaiger (ed.): Bertolt Brecht and Erwin Piscator. Experimental theater in Berlin in the 1920s . Christian Brandstätter, Vienna 2004, p. 13; Erwin Piscator. The letters. Volume 1. Edited by Peter Diezel. Berlin 2005, p. 123.

- ↑ The program of the Piscator stage. Number 1, September 1927. Oops, we're alive! by Ernst Toller . Edited by the Piscator stage. Berlin 1927, p. 16.

- ↑ The program of the Piscator stage. Number 1, September 1927. Oops, we're alive! by Ernst Toller . Edited by the Piscator stage. Berlin 1927, p. 5.

- ↑ In more detail: Beate Elisabeth Tharandt: Walter Gropius' Totaltheater revisited: a phenomenological study of the theater of the future . Southern Illinois University, Carbondale 1991. Stefan Woll: The total theater. A project by Walter Gropius and Erwin Piscator . Berlin 1984.

- ↑ John Willett: Erwin Piscator. The opening of the political age on the theater . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 1982, p. 122 f.

- ^ Judith Malina: The Piscator Notebook . Routledge Chapman & Hall, London 2012

- ↑ Werner Mittenzwei: Brecht and the fate of material aesthetics . In: Dialog 75. Positions and tendencies . Berlin 1975, pp. 9-44, here: pp. 19 f .; The same in: Who was Brecht. Change and development of views about Brecht in the mirror of meaning and form . Edited and introduced by Werner Mittenzwei. Berlin 1977, pp. 695-730.

- ↑ War and Peace . Based on the novel by Leo Tolstoy, retold and edited for the stage by Alfred Neumann, Erwin Piscator and Guntram Prüfer. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1955 (= Czech: Vojna a mír: Hra o 3 dějstvích . Dilia, Prague 1959. - English: War and peace . Macgibbon & Kee, London 1963. - Turkish: Savaş ve Barış . Yankı, Istanbul 1971 u. Ö .)

- ↑ Erwin Piscator: Letters. Volume 1: Berlin. Moscow 1909–1936 . Edited by Peter Diezel. B&S Siebenhaar, Berlin 2005, p. 189.

- ↑ Klaus Gleber: theater and public. Production and reception conditions of political theater using the example of Piscator 1920–1966 . Frankfurt am Main 1979, p. 266 f.

- ↑ John Willett: Erwin Piscator. The opening of the political age on the theater . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 1982, p. 35.

- ↑ Michael Lahr (Ed.): The Erwin Piscator Award / Der Erwin Piscator Prize. Elysium - between two continents, Munich 2013

- ^ Piscator - The Making of Eduardo Paolozzi's Euston Square Sculpture . Director: Murray Grigor. Everallin, Inverkeithing 1984 [documentary]

- ^ Willi Würz, Otto Schäfer: Ulm. Chronicle of a village . Vereinsring Ulm, Greifenstein 1996, p. 42

- ↑ Gert Heiland: He taught Marlon Brando to play . In: Wetzlarer Neue Zeitung , July 6, 2016

- ↑ More complete lists of Piscator's productions between 1920 and 1966 can be found in: John Willett: Erwin Piscator. The opening of the political age on the theater . Frankfurt am Main 1982, pp. 221-255. - Erwin Piscator. A working biography in 2 volumes. Vol. 2 . Edited by Knut Boeser, Renata Vatková. Berlin 1986, pp. 304-310.

- ↑ There is also the radio play Der Gouverneur und seine Männer based on Robert Penn Warren's novel All the King's Men in a stage adaptation by Erwin Piscator, which the SDR produced in 1959 under the direction of Karl Eberts.

- ↑ The deputy HR's audio play version from 1963 was also published as an audio book (Munich: der hörverlag 2003).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Piscator, Erwin |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Piscator, Erwin Friedrich Max (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German theater director, director and acting teacher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 17, 1893 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Greifenstein -Ulm, Hesse |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 30, 1966 |

| Place of death | Starnberg |