Kurt Tucholsky

Kurt Tucholsky (born January 9, 1890 in Berlin , † December 21, 1935 in Gothenburg ) was a German journalist and writer . He also wrote under the pseudonyms Kaspar Hauser , Peter Panter , Theobald Tiger and Ignaz Wrobel .

Tucholsky is one of the most important publicists of the Weimar Republic . As a politically committed journalist and temporarily co-editor of the weekly newspaper Die Weltbühne , he proved to be a social critic in the tradition of Heinrich Heine . At the same time he was a satirist , cabaret writer, songwriter, novelist, poet and critic (literature, film, music). He saw himself as a left-wing democrat, socialist, pacifist and anti-militarist and warned against the strengthening of the political right - especially in politics, the military and the judiciary - and against the threat posed by National Socialism .

Life

Childhood, youth, studies

Kurt Tucholsky's parents' house is at Lübecker Strasse 13 in Berlin-Moabit . He spent his early childhood in Szczecin , where his father had been transferred for professional reasons. The Jewish bank clerk Alex Tucholsky (1855–1905) had married his cousin Doris Tucholski (1861–1943) in 1887, with whom he had three children: Kurt, their eldest son, and Fritz and Ellen. In 1899 the family returned to Berlin.

While Tucholsky's relationship with his mother was clouded throughout his life, he loved and adored his father very much. Alex Tucholsky died in 1905. Doris Tucholski was deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp in May 1943 and murdered there.

The father had left his wife and children a considerable fortune that enabled Kurt to study free from financial worries. Kurt Tucholsky started school in the French grammar school in Berlin in 1899 . In 1903 he moved to the Königliche Wilhelms-Gymnasium , which he left in 1907 to prepare for the Abitur with a private teacher. After graduating from high school for external students in 1909, he began to study law in Berlin in October of the same year, the second semester of which he completed in the spring of 1910 at the University of Geneva .

Tucholsky's main interest was in literature, even during his studies. So he traveled to Prague with his friend, the draftsman Kurt Szafranski , in September 1911 to surprise the writer and Kafka friend Max Brod , whom he admired, with a visit and a miniature landscape he made himself. After meeting Tucholsky, Franz Kafka wrote about him in his diary on September 30, 1911:

“... a completely uniform person of 21 years. From the moderate and strong swing of the walking stick, which raises the shoulder youthfully, to the deliberate enjoyment and disregard of his own writing. Want to become a defender ... "

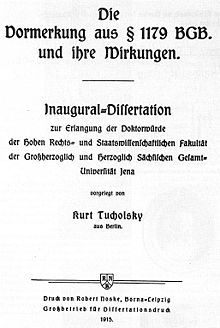

However, there was no legal career. Since Tucholsky was already very involved in journalism towards the end of his studies, he decided not to take the first state examination in law in 1913. This was tantamount to giving up a possible career as a lawyer. In order to obtain a degree anyway, he asked the University of Jena for admission to the doctorate for Dr. iur. His dissertation on mortgage law , submitted in January 1914, was initially rejected, but then accepted after several revisions. It bears the title "The reservation from § 1179 BGB and its effects". Tucholsky defended it on November 19, 1914 and passed it cum laude . After printing and delivery of the deposit copies , the doctoral certificate was handed over to him on May 12, 1915.

First successes as a writer

Tucholsky had already written his first journalistic work during his time as a schoolboy. In 1907 the satirical weekly magazine Ulk printed the short text Märchen , in which the 17-year-old made fun of Kaiser Wilhelm II's taste for art . During his studies he intensified his journalistic activities, including for the social democratic party organ Vorwärts . He campaigned for the SPD in 1911.

With Rheinsberg: A picture book for lovers ( Rheinsberg for short ), Tucholsky published a story in 1912 in which he took on a tone that was unusually fresh, playful and erotic for the time, and which made him known to a larger audience for the first time. In this book he processed a weekend together with Else Weil in August 1911. To promote sales of the book, Tucholsky and Szafranski, who had illustrated the story, opened a “book bar” on Berlin's Kurfürstendamm : everyone who bought a book could get there Poured a schnapps as an encore. However, the student gulp was discontinued after a few weeks.

A commitment that Tucholsky began in early 1913 became more long-term. On January 9, 1913, his first article appeared in the left-wing liberal theater magazine Die Schaubühne , the weekly newspaper of the publicist Siegfried Jacobsohn , renamed Die Weltbühne in 1918 , who remained Tucholsky's mentor and friend until his death. Tucholsky described the close relationship with him in 1933 in a résumé he wrote himself for the naturalization application in Sweden: “ The editor of the paper, Siegfried Jacobsohn, who died in 1926, Tucholsky owes everything he became. “In each issue of the Schaubühne , two to three articles, reviews or satires by Tucholsky usually appeared.

Soldier in the First World War

The beginning of the journalistic career was interrupted by the First World War. From August 1914 to October 1916 only one article by Tucholsky appeared. In contrast to many other writers and poets, he was not infected by the patriotic hurray mood at the beginning of the war. After receiving his doctorate in early 1915, he was drafted on April 10 of the same year and sent to the Eastern Front in Poland. There he first experienced trench warfare and served as a reinforcement soldier , then as a company clerk. From November 1916 on he brought out the field newspaper Der Flieger . In the administration of the artillery flying school in Alt-Autz in Courland (today Auce , Latvia ) he met his future second wife, Mary Gerold . Tucholsky saw the posts as clerk and field newspaper editor as a good opportunity to bypass a duty in the trenches. Looking back, he wrote:

“I avoided the war for three and a half years wherever I could. [...] I used many means to avoid getting shot and to avoid shooting - not even the worst means. But I would have used all of them, all without exception, if I had been forced: I would have spurned no bribery, no other criminal act. Many did the same. "

Some of these means were not without a certain comedy, as can be seen from a letter to Mary Gerold:

“One day I was given an old heavy rifle for the march. A rifle? And in the war? Never, I thought to myself. And leaned it against a hut. And went away. That was even noticed in our club at the time. I don't know how I ranked it - but somehow it worked. And it worked without a rifle ... "

During the war, Tucholsky made a close, lifelong friendship with Erich Danehl and Hans Fritsch . He later immortalized both as "Karlchen" and "Jakopp" in the travelogues Das Wirtshaus im Spessart and the monument at the Deutsches Eck , in the novel Schloss Gripsholm and in other texts.

The lawyer Danehl helped Tucholsky in 1918 to be assigned to Romania as deputy sergeant and field police commissioner. There, in Turnu Severin , he was baptized Protestant in the summer of 1918. He had resigned from the Jewish community on July 1, 1914.

Although Tucholsky had participated in a competition for the 9th War Loan in August 1918 , he returned from the war in autumn 1918 as a staunch anti-militarist and pacifist.

Battle for the Republic

In December 1918, Tucholsky took over the editor-in-chief of " Ulk ", which he held until April 1920. Ulk was the weekly satirical supplement to the liberal Berliner Tageblatt published by Rudolf Mosse .

He also worked regularly for the Weltbühne again. In order not to let the left-democratic weekly newspaper appear too “Tucholsky-heavy”, he had already acquired three pseudonyms in 1913, which he retained until the end of his journalistic work: Ignaz Wrobel , Theobald Tiger and Peter Panter . Since Theobald Tiger was temporarily reserved for the joke , poems appeared on the Weltbühne in December 1918 for the first time under a fourth pseudonym, Kaspar Hauser . Very rarely, a total of only five times, he published texts under the names Paulus Bünzly, Theobald Körner and Old Shatterhand , although the attribution of the latter pseudonym is controversial in research. In retrospect, Tucholsky explained the origin of his pseudonyms:

“The alliterating siblings are the children of a legal tutor from Berlin. [...] The people on whom he demonstrated the civil code and the seizure orders and the code of criminal procedure were not called A and B, not: heir and not testator. Their names were Benno Büffel and Theobald Tiger; Peter Panter and Isidor Iltis and Leopold Löwe and so through the whole alphabet. […]

Wrobel - that was the name of our arithmetic book; and because the name Ignaz struck me as particularly ugly, scruffy and utterly abhorrent, I committed this little act of self-destruction and thus baptized a part of my being.

Kaspar Hauser does not need to be introduced. "

The many pseudonyms had become necessary because there was hardly a rubric to which Tucholsky had nothing to contribute: from political editorials and court reports to glosses and satires to poems and book reviews. He also composed texts, songs and couplets for cabaret - for example for the Schall und Rauch stage - and for singers like Claire Waldoff and Trude Hesterberg . In October 1919, Tucholsky's collection of poems, Fromme Gesänge, was published .

In the immediate interwar period , Tucholsky's engagement occurred which he regretted in retrospect: his very well-paid work for the Pieron propaganda magazine from July 1920 to April 1921 . On behalf of the Reich government, the magazine was supposed to create anti-Polish sentiment before the referendum on the final German-Polish border in Upper Silesia . The demagoguery and agitation of Pieron , strongly criticized by other newspapers , ultimately resulted in Tucholsky no longer being allowed to write for papers of the USPD . In June 1922, a USPD arbitration commission acquitted him of the charge of having worked against the party's efforts. However, Tucholsky later judged his behavior:

"At that time, large funds were pumped into the corrupt national body from both sides as later into the Ruhr - I myself had my hands in this vat, I shouldn't have done it, and I regret what I did."

As a political author, Tucholsky had already started the anti-militarist article series Militaria on the Weltbühne in January 1919 , an attack on the Wilhelmine spirit of the officers, which he saw further brutalized by the war and which lived on in the republic. His own attitude as a soldier during the war should not have differed significantly from that which he criticized the German officer corps so sharply. Biographers therefore see the “Militaria” articles as “a kind of public self-analysis” ( Hepp ). The first article in the series states, among other things:

“We have to eat up what a degenerate militarism has gotten us into.

Only by completely turning away from this shameful epoch can we regain order. It is not Spartacus; Neither is the officer who saw his own people as a means to an end - what will it be in the end?

The upright German. "

Tucholsky also vehemently denounced the numerous political murders that shook the Weimar Republic in the first few years. Attacks were repeatedly carried out on left-wing, pacifist or liberal politicians and publicists, for example on Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg , Walther Rathenau , Matthias Erzberger , Philipp Scheidemann and Maximilian Harden . As a trial observer in proceedings against radical right-wing murderers , he found that the judges generally shared the monarchist and nationalist views of the accused and sympathized with them. In his 1922 article in the Harden Trial , he wrote:

“The German political murder of the past four years is schematic and tightly organized. [...] Everything is clear from the start: Incitement by unknown donors, the deed (always from behind), sloppy investigations, lazy excuses, a few phrases, pathetic pince-nez, mild punishments, reprieve, perks - “Carry on!” [...]

That is not bad justice. This is not a flawed justice system. This is not justice at all. [...] The Balkans and South America will forbid a comparison with this Germany. "

Tucholsky also did not spare criticism of democratic politicians who, in his opinion, were too lenient with their opponents. After the murder of Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau in 1922, he made an appeal to the self-respect of the republic in a poem:

"Get up once! Hit it with your fist!

Don't go back to sleep after a fortnight!

Out with your monarchist judge,

with officers - and with the lights that live

on you and that sabotage you and

smear swastikas on your houses.

[…]

Four years of murder - that is enough, God knows.

You are now standing before your last breath.

Show what you are Judge yourself.

Die or Fight. There is no third. "

Tucholsky therefore did not stop at his journalistic activities, but was also directly involved in politics. In October 1919, for example, he was involved in the founding of the Peace League for those who participated in the war and was involved in the USPD. Membership in a party never stopped Tucholsky from criticizing its members. For example, he judged Rudolf Hilferding's performance as editor-in-chief of the USPD newspaper Freiheit :

"Dr. Rudolf Hilferding was sent to the editorial office of Freedom from the Reich Association for Combating Social Democracy. He managed to run down the dangerous paper in two years to such an extent that both a paper and a danger can no longer be spoken of. "

He went particularly hard with the SPD , whose leadership he accused of failure, even betrayal of its own supporters during the November Revolution. He wrote about Friedrich Ebert in the Harden trial in 1922 :

"And above everything is this president, who threw his convictions behind him the moment he was able to realize them."

In the high phase of inflation Tucholsky was forced to postpone his journalistic work in favor of business. But not only financial reasons should have played a role for this step. In the autumn of 1922 he suffered from severe depression, doubted the sense of the letter and is said to have even attempted suicide for the first time. On March 1, 1923, he finally joined the Berlin bank Bett, Simon & Co. , where he worked as the private secretary of the senior boss Hugo Simon . But on February 15, 1924, he signed another employee contract with Siegfried Jacobsohn . As a correspondent for the Weltbühne and the respected Vossische Zeitung , he went to Paris in the spring of 1924.

In 1924, there were also great changes in Tucholsky's personal life. In February 1924 he divorced the doctor Else Weil , whom he had married in May 1920. On August 30, 1924, he finally married Mary Gerold , with whom he had been in correspondence since he had been detached from Alt-Autz. When they met again in Berlin in the spring of 1920, the two had discovered that they had become estranged from each other. In 1926 Kurt and Mary Tucholsky moved into a house in the Paris suburb of Le Vésinet . However, it should also be shown in Paris that they could not stand each other for a long time.

Between France and Germany

Like his role model Heinrich Heine , Tucholsky lived most of the time abroad after moving to Paris and only returned to Germany sporadically. The distance, however, sharpened his ability to perceive the affairs of Germany and the Germans. He continued to participate in the political debates at home through the world stage . In addition, like Heine in the 19th century, he tried to promote mutual understanding between Germans and French. ( A book on the Pyrenees , published in 1927, caused völkisch circles to refer to him as a “French favorite” and “non-German”). Tucholsky, who was accepted into the Masonic Lodge Zur Morgenröte in Berlin - part of the Masonic Association of the Rising Sun - on March 24, 1924 , visited lodges in Paris and in June 1925 became a member of the two lodges L'Effort and Les Zélés Philanthropes in Paris (Grand Orient de France).

In 1926, Tucholsky was elected to the board of the Revolutionary Pacifists group founded by Kurt Hiller .

When Siegfried Jacobsohn died in December 1926, Kurt Tucholsky immediately declared himself ready to take over the management of the Weltbühne . Since he did not like the work as the "headline editor" and he would have had to return to Berlin permanently, he soon handed the sheet over to his colleague Carl von Ossietzky . As a co-editor, he always made sure that unorthodox contributions were also published, such as B. Kurt Hiller delivered.

In 1927 and 1928 his essayistic travelogue Ein Pyreneesbuch , the text collection Mit 5 PS (which meant his name and the four pseudonyms) and the smile of the Mona Lisa were published . With the literary figures of Mr. Wendriner and Lottchen , he described typical Berlin characters of his time.

At the same time he remained a critical observer of the conditions in Germany. In April 1927, for example, in the three-part article German judges in the Weltbühne , he denounced what he saw as the reactionary judiciary of the Weimar Republic. In Tucholsky's opinion, a second, this time successful, revolution was necessary to bring about a fundamental change in the undemocratic situation. He wrote:

“Is there no resistance? There is only one great, effective, and serious class struggle : the anti-democratic, derisive, and consciously unjust class struggle for the idea of justice . ... There is only one thing to clean up a bureaucracy. That one word that I don't want to put here because it has lost its shudder for those in power. This word means: upheaval. General cleaning. Clean up. Ventilation."

In 1928, he argued in a very similar way in the article November Revolution , a review of ten years of the republic: “ The German revolution is still pending. “Tucholsky temporarily approached the KPD and published class-struggle propaganda poems in the party- affiliated AIZ Das Gedicht Asyl für Homeless! ends with the memorable verse:

“Charities, human, are nothing but steam.

Get your rights in the class struggle -! "

During his time abroad, too, Tucholsky had to deal with political opponents who felt offended or attacked by his statements. Because of the poem Gesang der English choirboys , a process of blasphemy was initiated against him in 1928 .

In the same year Kurt and Mary Tucholsky finally separated - the divorce took place in 1933. Tucholsky had already met Lisa Matthias in 1927 , with whom he spent a vacation in Sweden in 1929. This stay inspired him to write the short novel Schloß Gripsholm , published by Rowohlt Verlag in 1931 , in which the youthful lightheartedness and lightness of Rheinsberg once again echoed.

The contrast to the socially critical work Deutschland, Deutschland über alles , published in 1929 together with the graphic artist John Heartfield , could hardly be greater. In it Tucholsky manages the feat of combining the sharpest attacks on everything he hates about Germany of his time with a declaration of love for the country. In the last chapter of the book, under the heading Heimat, it says:

“Now we have said no on 225 pages, no out of pity and no out of love, no out of hate and no out of passion - and now we want to say yes too. Yes -: to the landscape and the country of Germany. The country in which we were born and whose language we speak. [...]

And now I want to tell you something: It is not true that those who call themselves 'national' and are nothing but bourgeois-militaristic have leased this country and its language for themselves. Neither the government representative in a frock coat, nor the senior teacher, nor the ladies and gentlemen in steel helmets are Germany alone. We're still there too. [...]

Germany is a divided country. We are part of him. And in all opposites stands - unshakable, without a flag, without an organ grinder, without sentimentality and without a drawn sword - the silent love for our homeland. "

Trials against the Weltbühne and Ossietzky

In March 1929 , the Weltbühne published an article by the journalist Walter Kreiser entitled “Windy news from German aviation”, which dealt, among other things, with the prohibited aeronautical armament of the Reichswehr . On the basis of this publication, since August 1929 the Oberreichsanwalt investigated Kreiser and Carl von Ossietzky for treason and the betrayal of military secrets. Although the article merely reproduced facts that were already known, Ossietzky was sentenced to 18 months imprisonment for espionage in the 1931 Weltbühne trial .

Ossietzky was also sued for the famous Tucholsky sentence “ Soldiers are murderers ”, but was acquitted in July 1932 because the court did not see the sentence as a disparagement of the Reichswehr. Tucholsky himself had not been charged because he lived abroad. He had considered coming to Germany for this trial, as Ossietzky was already in prison for the aviation article, but in the end the situation seemed too risky to him. He feared falling into the hands of the National Socialists. However, it was clear to him that his absence would not make a good impression. “ To the outside world , a remnant of earth remains embarrassing to carry. There is something about desertion, abroad, abandoning comrade Oss in prison, ”he wrote to Mary Gerold, who“… drew his attention so nicely that the Nazis' life was in danger. ”A few days before his death he wrote again that he had regretted the decision made in the summer of 1932:

“But in the case of Oss I didn't come once, I failed at the time, it was a mixture of laziness, cowardice, disgust, contempt - and I should have come anyway. I know all that it wouldn't have helped, that we both would certainly have been condemned, that I might have fallen into the clutches of these animals - but there remains a trace of guilt. "

Journalistic silence and exile

Since the investigations and the trials against Ossietzky, Kurt Tucholsky saw the possibilities for critical journalism in Germany severely limited. In 1929 he moved permanently to Sweden. He rented the villa “Nedsjölund” in Hindås near Gothenburg . It hit him deeply when it became clear to him during this time that all of his warnings had gone unheeded and that his advocacy for the republic, for democracy and human rights apparently had no effect. As a clear-eyed observer of German politics, he recognized the dangers looming with Hitler . "You are preparing for the journey to the Third Reich, " he wrote years before the transfer of power , and he had no illusions as to where Hitler's chancellorship would lead the country. Erich Kästner testified to this in retrospect in 1946, when he described the writer as a “fat little Berliner” who “wanted to stop a catastrophe with the typewriter”.

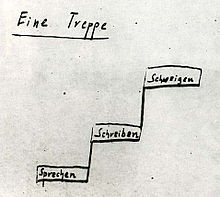

From 1931 on, Tucholsky became increasingly silent as a journalist. The end of his relationship with Lisa Matthias, the sudden death of his close friend Hans Fritsch and a chronic respiratory and nasal ailment that required five operations had heightened his mood of resignation. Tucholsky's last major contribution appeared on the Weltbühne on November 8, 1932 . It was just snippets , as he called his aphorisms. On January 17, 1933, he reported to the Weltbühne again with a small note from Basel. He visibly lacked the strength for larger literary forms. Although he submitted an exposé for a novel to Rowohlt Verlag , political developments in Germany prevented its realization. In 1933 the National Socialists banned the world stage , burned Tucholsky's books and deprived him of his German citizenship .

His letters, which have been published since the early 1960s, provide information about Tucholsky's last years and his thoughts on developments in Germany and Europe. They were addressed to friends such as Walter Hasenclever or to his last lover, the Zurich doctor Hedwig Müller, whom he called "Nuuna". He also enclosed loose diary sheets with the letters to Nuuna, which are now known as Q diaries . In it and in the letters, Tucholsky occasionally referred to himself as a "stopped German" and "stopped poet". He wrote to Hasenclever on April 11, 1933:

“I don't need to tell you that our world ceased to exist in Germany. And therefore:

I will not shut up until then. You don't whistle against an ocean. "

Nor did he succumb to the illusion of many exiles that Hitler's dictatorship would soon collapse. With a realistic eye, he found that the majority of Germans were coming to terms with the dictatorship and that even abroad accepted Hitler's rule. He expected a war within a few years.

Tucholsky strictly refused to participate in the emerging exile press. On the one hand, he did not see himself as an emigrant, since he had left Germany in 1924, and was considering applying for Swedish citizenship. In a moving letter to Mary Gerold, he described his deeper reasons why he no longer dealt with Germany publicly:

“I didn't publish a line about what happened there - not at all requests. It is none of my business. It's not cowardice - that's what it takes to write in these cheese sheets! But I'm au-dessus de la mêlée, it's none of my business. I'm done with it. "

Inwardly, however, he was not finished with everything, and he did take part in developments in Germany and Europe. In order to stand by the imprisoned Ossietzky, he also thought of going public again. Shortly before his death, he planned to settle accounts in a sharp article with the Norwegian poet Knut Hamsun, whom he once admired . Hamsun had openly spoken out in favor of the Hitler regime and attacked Carl von Ossietzky, who was incarcerated in the Esterwegen concentration camp without being able to defend himself . Behind the scenes, Tucholsky also supported the awarding of the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize to the imprisoned friend. In fact, Ossietzky received the award the following year retrospectively for 1935. However, Kurt Tucholsky did not live to see the success of his efforts.

In his last letter to the writer Arnold Zweig, who emigrated to Palestine , on December 15, 1935, he primarily dealt critically with the lack of resistance by German Jews to the Nazi regime. In it, he resignedly took stock of his political commitment in and for Germany:

“It's bitter to see. I have known since 1929 - I went on a lecture tour and saw “our people” face to face, in front of the podium, opponents and supporters, and then I understood it, and from then on I became more and more quiet. My life is too precious for me to stand under an apple tree and ask it to produce pears. I do not anymore. I have nothing more to do with this country, whose language I speak as little as possible. May it perish - may it conquer Russia - I'm done with it. "

death

From October 14 to November 4, 1935, Tucholsky was in inpatient treatment because of constant stomach problems. Since that hospital stay, he has not been able to sleep without barbiturates . On the evening of December 20, 1935, he overdosed on Veronal sleeping pills at his home in Hindås . The next day he was found lying in a coma and taken to Sahlgrensche Hospital in Gothenburg . Kurt Tucholsky died there on the evening of December 21st. For a long time it was considered certain that Tucholsky wanted to commit suicide - a thesis that, however, was questioned by Tucholsky's biographer Michael Hepp in 1993. Hepp found evidence of an accidental overdose of the drug, i.e. unintentional suicide.

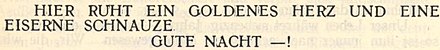

Kurt Tucholsky's ashes were buried under an oak tree near Gripsholm Castle in Mariefred, Sweden , in the summer of 1936 . The grave slab with the inscription “Everything transient is just a parable” from Goethe's Faust II was only placed on the grave after the end of the Second World War. Tucholsky himself had proposed the following funeral motto for himself in the satire Requiem in 1923 :

Reception and individual aspects

Tucholsky was one of the most sought-after and best-paid journalists of the Weimar Republic. In the 25 years of his activity he published more than 3,000 articles in almost 100 publications, most of them, around 1,600, in the weekly magazine Die Weltbühne . During his lifetime, seven anthologies with shorter texts and poems were published, some of which achieved dozens of editions. Some of Tucholsky's works and statements polarize to this day, as evidenced by the disputes over his sentence “ Soldiers are murderers ” up to the recent past. His criticism of politics, society, the military, justice and literature, but also of parts of German Jewry, repeatedly provoked opposition.

The Kurt Tucholsky Literature Museum , which documents his life and work in detail, is located in Rheinsberg Castle . A large part of Tucholsky's estate is in the German Literature Archive in Marbach . Pieces of it can be seen in the permanent exhibition in the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach am Neckar .

The political writer

Tucholsky's role as a political journalist has always been controversial. He outlined his self-image as a liberal , left-wing intellectual in the programmatic text “We Negatives”, in which as early as March 1919 he had to take a stand on the allegations that the young republic was not viewed positively enough. His conclusion at the time was:

“We cannot say yes to a people who, even today, are in a constitution which, if the war had happened to end happily, would have led to fears of the worst. We cannot say yes to a country that is obsessed with collectivities and where the corporation is far above the individual. "

Tucholsky was increasingly critical of the Weimar Republic. In his eyes, the November Revolution had brought no real progress:

“How did you baptize that? Revolution? That wasn't one. "

The same demons reigned in schools, universities, administrations and courts, and the German responsibility for the First World War was still denied. Instead of pursuing a real peace policy, the next war is secretly being prepared. From all these conditions he drew the conclusion in the spring of 1928:

“We consider nation-state war to be a crime, and we fight it where we can, when we can, by whatever means we can. We are traitors. But we are betraying a state that we deny in favor of a country that we love, for peace and for our real fatherland: Europe. "

Despite this disappointment, Tucholsky had not ceased to attack the declared enemies of the republic and democracy in the military, justice and administration, in the old monarchist-minded elites and in the new, anti-democratic nationalist movements . At times Tucholsky, who had been a member of the USPD from 1920 to 1922, also approached the KPD, although as a bourgeois writer he always kept his distance from the communist party functionaries.

In view of his uncompromising attitude towards the National Socialists, it was also logical that Tucholsky found his name on the First Expatriation List of the German Reich in 1933 and that his works were banned after 1933. At the book burnings by students in Berlin and other cities on May 10th, he and Ossietzky were explicitly named: “Against impudence and presumption, for respect and reverence for the immortal German national spirit! Devouring, Flame, and the writings of Tucholsky and Ossietzky! " Tucholsky commented appropriate messages only indifferent, as in a letter to Walter Hasenclever of 17 May 1933

“In Frankfurt they dragged our books on an ox cart to the place of execution. Like a traditional costume club of senior teachers. But now to the more serious. ... "

In the post-war period, however, there were also voices in the Federal Republic that left literary figures such as Tucholsky and Bertolt Brecht were partly to blame for the failure of the Weimar Republic. With their merciless criticism, magazines like Weltbühne ultimately played into the hands of the National Socialists, was the tenor of the allegations. One of the best-known representatives of this view was the historian Golo Mann . He wrote in 1958:

“The clairvoyant malice with which Kurt Tucholsky mocked the republic, all its lameness and falsehood, reminded from a distance of Heinrich Heine. There was a bit in him of the great poet's wit and hatred, but unfortunately little of his love. Radical literature was able to criticize, mock, unmask, and thereby acquired a slight superiority that did not yet prove the solidity of its own character. She was used to her craft from the time of the emperor and continued it under the republic, which also had no shortage of targets for her scorn. What was the use? "

His colleague Heinrich August Winkler thinks that the preferred target of Tucholsky's ridicule was the social democracy with its necessary compromises:

“In effect, the fight that Tucholsky and his friends waged against social democracy was a fight against parliamentary democracy. In this respect the intellectuals of the circle around the 'world stage' were much closer to the anti-parliamentarians of the 'conservative revolution' than either side was aware of. "

Tucholsky himself always saw his criticism as constructive: In his eyes, the failure of Weimar had nothing to do with the fact that authors like him had too much, but with the fact that they achieved too little effect. In May 1931 he wrote to the publicist Franz Hammer :

“What I sometimes worry about is the impact of my work. Does she have one? (I don't mean success; it leaves me cold.) But it sometimes seems so terribly ineffective to me: you write and work - and what happens in real life in the administration? Can you get these evil, tormented, agonizing inverted institutional women away? Are the sadists leaving? Will the bureaucrats be fired [...]? Sometimes that depresses me. "

A passage from the letter to Hasenclever of May 17, 1933 already quoted reads like an anticipated response to the critics of the post-war period:

“I'm slowly going megalomaniac - when I read how I ruined Germany. But for twenty years the same thing has always pained me: that I couldn't get a policeman off his post either. "

Tucholsky and the labor movement

Tucholsky saw himself as a left-wing intellectual who stood up for the labor movement. He was involved in the SPD before the First World War, but since the November Revolution of 1918 he increasingly distanced himself from this party, whose leadership he accused of betraying its base. At that time , the party chairman Friedrich Ebert had concluded a secret agreement with General Wilhelm Groener , the chief of the Supreme Army Command , to suppress the revolution, which in the eyes of the SPD party leadership threatened to escalate. Ebert had promised Groener that the military, judiciary and administrative structures from the German Empire would also be preserved in the republic.

Tucholsky was a member of the USPD between 1920 and 1922 . After this left-wing Social Democratic party split again in 1922 and rejoined the SPD with a large number of its remaining supporters, Tucholsky was also a member of the SPD for a short time. The sources are unclear about the duration of this membership. Towards the end of the 1920s he got closer to the KPD, but made it a point not to be a communist. Overall, he insisted on an independent stand against all workers' parties, apart from party discipline.

The fact that he did not regard the world stage as a dogmatic preaching organ but as a forum for discussion for the entire left earned him the following criticism from the communist magazine Die Front in 1929 :

“The tragedy of Germany is not least the pitiful half-measure of its 'left' intellectuals, who reigned over the parties because 'it is not made easy for one of the ranks' (to speak with Kurt Tucholsky). These people failed brilliantly in 1918, they still fail today. "

Tucholsky replied in his article "The Role of the Intellectual in the Party":

“The intellectual writes behind the ears:

He is only authorized to enter the leadership of a workers 'party under two conditions: if he has sociological knowledge and if he makes and has made political sacrifices for the workers' cause. [...]

The party writes behind its ears:

Almost every intellectual who comes to it is a runaway citizen. A certain mistrust is in place. But this mistrust must not exceed any measure. [...]

Only one thing matters: to work for the common cause. "

After the Second World War, attempts were made in the GDR - unlike in the Federal Republic - to include Tucholsky in their own tradition. In doing so, however, the fact that he had strongly rejected the KPD's course , which he held responsible for the fragmentation of the left and the victory of the National Socialists, was suppressed. In a letter to the journalist Heinz Pol , shortly after Hitler came to power on April 7, 1933, when boycott measures against Germany were being discussed across Europe:

“It also seems important to me: Russia's attitude towards Germany. If I were a communist: I spat on this party. Is that a way of leaving people in the ink because you need the German loans? "

In a letter to the same addressee on April 20, 1933, it says:

“The KPD did stupid things in Germany from start to finish, they didn't understand their people on the street, they just didn't have the masses behind them. And how did Moscow behave when it went wrong? […] And then the Russians don't even have the courage to learn from their defeat - because it is their defeat? After bitter experiences, they too will one day see that there is nothing with:

the absolute totality of state rule;

with one-sided vulgar materialism;

with the cheeky audacity to knock the whole world over a skirting board that doesn't even fit Moscow. "

The literary critic and poet

As a literary critic , Kurt Tucholsky was one of the most influential German publicists of his time. In his permanent, multi-page column "On the bedside table", which appeared in the Weltbühne , he often discussed half a dozen books at once. In total, he reviewed more than 500 literary works. Tucholsky saw it as the "first endeavor" of his book review , "not to play the literary pope". His political views regularly flowed into his literary reviews: "Like no other, Kurt Tucholsky embodies the politically committed type of left-wing intellectual reviewer."

One of his achievements in this area is to have been one of the first to draw attention to the work of Franz Kafka . As early as 1913, he described Kafka's prose in his first book publication, Consideration , as “made deeply and with the most sensitive fingers” ; In his review , he described the fragment of the novel The Trial as "the scariest and most powerful book in recent years".

On the other hand, he was critical of James Joyce's Ulysses : “Whole parts of 'Ulysses' are simply boring.” But he also wrote about individual passages: “This is probably more than literature - in any case, it is the very best” and finally made a comparison with “ Liebig's meat extract . You can't eat it. But many more soups will be prepared with it. "

As a poet of chansons and couplets, Tucholsky contributed to opening up these genres for the German language world. "The effort it takes to wrest a chanson from the German language - and now even one for the lecture - is inversely proportional to the validity of these things," he complained in the text, "Shaken off his sleeve". As a lyricist, however, he saw himself only as a “talent”, in contrast to the “man of the century” Heinrich Heine . The poem “Mother's Hands”, which appeared in the AIZ in 1929 , is a typical example of his “ practical poetry” , as Tucholsky described this poetic trend, of which Erich Kästner was the main representative , in an article of the same name. The Tucholsky repertoire in school reading books includes poems such as “Augen in der Großstadt”, which was set to music by artists as diverse as Udo Lindenberg , Jasmin Tabatabai , Das Ideal and Die Perlen .

Tucholsky and Judaism

Tucholsky's attitude to Judaism is also viewed as controversial .

The Jewish scientist Gershom Scholem described him as one of the "most gifted and repulsive Jewish anti-Semites". The basis for this judgment was, among other things, the "Wendriner" stories, which, in Scholem's view, depicted the Jewish bourgeoisie in "most merciless nude photos". On the other hand, it was argued that Tucholsky in the figure of "Herr Wendriner" does not expose the Jews, but the bourgeois. His aim was to denounce the senseless mentality of a section of the conservative Jewish bourgeoisie, which in his opinion would accept even the greatest humiliations from a nationalist environment as long as it could go about its business.

The back of a photograph from around 1908 from the Kaufhaus des Westens studio in Berlin was dedicated to the Tucholsky portrayed on it: “Outside Jewish and ingenious / inside a little immoral / never alone, always à deux: - / the neveu! - K. "

Wolfgang Benz considers Tucholsky's sentence “and that is the ghetto: that one accepts the ghetto” as the key to understanding Tucholsky's aversion and resentment towards the German Jews: Tucholsky said the increasing discrimination and disenfranchisement of Jews in Germany was his own defeat and injury understood, which he tried to soften by distancing himself and therefore accused the Jews in Germany of supposed passivity, an attitude of adjustment and a lack of willingness to demonstrate counter-reactions. Such reserved judgments against German Jewry were made early on in Tucholsky's career. In his farewell letter to his brother Fritz, he even claims that centuries of life in the ghetto are not an “explanation” or a “cause” but “a symptom”.

From the point of view of the conservatives and right-wing extremists - including the German national Jews - Tucholsky portrayed the almost perfect enemy image of the “corrosive, Jewish writer”. The fact that Tucholsky left Judaism in 1914 and was baptized as a Protestant played no role for these critics . The argument that is still put forward against Jews today that they themselves provoked anti-Semitism with their statements has already been used against Tucholsky. In his literary history of the German people in 1941 , Josef Nadler expressed the hatred of the National Socialists for the deceased in the clearest possible way: "No people on earth has ever been so reviled in their own language as the German by Tucholsky."

Astonishingly, Tucholsky devoted his last long letter to the situation of German Jewry. To Arnold Zweig , who emigrated to Palestine , he wrote: “It is not true that the Germans are Jewish. The German Jews are banned . "

Tucholsky and the women

Ever since Lisa Matthias ' autobiography Ich war Tucholsky's Lottchen was published , the Tucholsky researchers have had enough material to speculate extensively about Tucholsky's relationship with women . In her memoirs, Matthias described Tucholsky as an erotomaniac incapable of relationships , who had cheated on her, herself a lover, with several women at the same time. The publication of the memoirs was perceived as a scandal in 1962 because, in the opinion of literary critics , Matthias had made Tucholsky's sexuality too much an issue. The fact that she described Tucholsky "in even less than underpants" ( Walther Karsch ) is not true, however. Tucholsky's first wife, Else Weil, also confirmed that he hadn't been very strict about loyalty. From her the sentence has been passed down: "When I had to step over the ladies to get into my bed, I got a divorce." Tucholsky's second wife Mary Gerold , on the other hand, never commented on her husband's private life.

Biographers usually blame his bad relationship with his mother for the failure of Tucholsky's two marriages, under whose rule he suffered after his father's untimely death. Tucholsky and his two siblings unanimously described them as the tyrannical type of "single housemealers ". This made it impossible for the "erotically slightly irritated woman man" ( Raddatz ) to endure the closeness of a woman in the long term. Shortly before his death, when he was still in a relationship with Hedwig Müller and Gertrude Meyer, Tucholsky again confessed to his second wife, Mary Gerold, whom he made his sole heir. In his farewell letter to her he wrote about himself: “Has held a lump of gold in his hand and has bent down for arithmetic pennies; did not understand and did stupid things, did not betray, but cheated, and did not understand. "

Gerhard Zwerenz advocates the thesis in his biography that Tucholsky was not able to “accept intellectual abilities in women without masculinizing women at the same time”. As evidence for this, he cites statements such as: "Frankfurt has produced two great men: Goethe and Gussy Holl ", or the fact that he usually addressed Mary Gerold as "He" in his letters. Ultimately, subsequent psychological considerations of this kind always remain speculation. What is certain is that Tucholsky propagated an image of women that was progressive for the time in his stories on Rheinsberg and Gripsholm Castle . He also supported the work of the feminist Helene Stöcker with articles in the sexual reform magazine Die Neue Generation .

Positively portrayed female figures in his works, such as Claire, the Princess and Billie, are independent characters who live out their sexuality according to their own ideas and who do not submit to moral concepts that have not been outdated . This also applies to the figure of the flighty Lottie. Tucholsky expressed his aversion to asexual intellectuals in reform dress in the figure of Lissy Aachner in Rheinsberg . The malicious director of the children's home in Gripsholm Castle , on the other hand, corresponds more to the type that Tucholsky might have seen in his mother Doris.

See also

- Kurt Tucholsky Society with the Kurt Tucholsky Prize (Germany)

- Tucholsky Prize (Sweden) , awarded by the Swedish section of the PEN

- The Trench , Chanson (1926)

factories

- Rheinsberg: A picture book for lovers . Pictures by Kurt Szafranski . Axel Juncker Verlag, Berlin 1912. Current edition: Anaconda, Cologne 2010, ISBN 978-3-86647-498-7 . Audio book: radio play with Kurt Böwe et al., Der Audio Verlag , 2001, ISBN 3-89813-158-0 ; read by Anna Thalbach , Argon Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-86610-746-5 .

- The time saver. Grotesques by Ignaz Wrobel. Reuss & Pollack, Berlin 1914. Facsimile: Edited by Annemarie Stoltenberg , Verlag am Galgenberg, Hamburg 1988, ISBN 3-925387-13-7 .

- The reservation from § 1179 BGB and its effects. Dissertation, University of Jena 1915. New edition: Verlag consassis, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-937416-60-1 .

- Pious chants. By Theobald Tiger with a preface by Ignaz Wrobel. Felix Lehmann Verlag, Charlottenburg 1919 (= Selected Works. Volume 1) - 4th edition. Verlag Berlin, Berlin 1979, DNB 790199203 .

- Daydreams at Prussian chimneys. By Peter Panter, with pictures by Alfons Wölfe . Felix Lehmann Verlag, Charlottenburg 1920. New edition: WFB Verlagsgruppe, Bad Schwartau 2009, ISBN 978-3-86672-300-9 .

- Tamerlane. From the revue We stand wrong by Carl Rössler . Lyrics by Theobald Tiger. Music by Rudolph Nelson . Drei Masken Verlag, Berlin / Munich / Vienna 1922.

- as Peter Panter: A Book of the Pyrenees . Verlag Die Schmiede, Berlin 1927. Current edition: Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-458-34993-8 .

- With 5 hp. Rowohlt Verlag, Berlin 1928. Current edition: 1985, ISBN 3-499-10131-9 .

- Germany Germany above everything. A picture book by Kurt Tucholsky and many photographers. Assembled by John Heartfield . Universum Bücherei für alle , Berlin 1929. Current edition: Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1996, ISBN 3-499-14611-8 .

- The Mona Lisa's smile. [1928] Rowohlt, Berlin 1929; 5th edition: Verlag Volk und Welt 1985.

- Learn to laugh without crying. Rowohlt Verlag, Berlin 1931. Reproduction true to the original: Olms Verlag, Hildesheim et al. 2008, ISBN 978-3-487-13618-9 or in Marixverlag, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3-7374-0980-3 ; Audio book: read by Jürgen von der Lippe , Bell-Musik, Aichtal 2008, ISBN 978-3-940994-01-1 .

- Gripsholm Castle . Rowohlt Verlag, Berlin 1931. Current edition: Greifenverlag, Rudolstadt / Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-86939-239-4 .

- Walter Hasenclever , Kurt Tucholsky: Christopher Columbus or The Discovery of America. Comedy in one foreplay and six pictures. By Walter Hasenclever and Peter Panter (1932). Ms. Neuer Bühnenverlag, Zurich 1935 / Das Arsenal, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-921810-72-8 .

- Berlin! Berlin! There is no sky over this city. Berlinica, Berlin 2017 (current edition), ISBN 978-3-96026-023-3 .

Work editions

- Complete edition. Texts and letters . Edited by Antje Bonitz, Dirk Grathoff, Michael Hepp, Gerhard Kraiker. 22 volumes. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1996 ff., ISBN 3-498-06530-0 ff.

- Collected Works . Volumes 1-3, 1907-1932. Edited by Mary Gerold-Tucholsky and Fritz J. Raddatz. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1960.

- Collected works in 10 volumes . Edited by Mary Gerold-Tucholsky and Fritz J. Raddatz. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1975, ISBN 3-499-29011-1 .

- German pace. Collected Works. Supplementary volume 1 . Edited by Mary Gerold-Tucholsky and J. Raddatz. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1985, ISBN 3-498-06483-5 .

- Republic against its will. Collected Works. Supplementary volume 2 . Edited by Fritz J. Raddatz. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1989, ISBN 3-498-06497-5 .

- Selected works in six volumes . Edited by Roland Links , Volk und Welt , Berlin 1969–1973.

- Kurt Tucholsky - Works - Letters - Materials , Third, unchanged edition, Directmedia • Berlin 2007, Digital Library 15, CD-ROM, setup, editing: Mathias Bertram , editorial assistance: Martin Mertens, Sylvia Zirden, Copyright 1998/2007 Directmedia Publishing GmbH , Berlin, ISBN 978-3-89853-415-4 .

Notes, letters and diaries

- Selected letters 1913–1935. Edited by Mary Gerold-Tucholsky and Fritz J. Raddatz. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1962.

- Letters to a Catholic. 1929-1931. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1969, 1970, ISBN 3-498-06463-0 .

- Letters from the silence. 1932-1935. Letters to Nuuna. Edited by Mary Gerold-Tucholsky and Gustav Huonker. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1977, 1990, ISBN 3-499-15410-2 .

- The Q diaries. 1934-1935. Edited by Mary Gerold-Tucholsky and Gustav Huonker. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1978, 1985, ISBN 3-499-15604-0 .

- Our unlived life. Letters to Mary. Edited by Fritz J. Raddatz. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1982, 1990, ISBN 3-499-12752-0 .

- I can't write without lying. Letters 1913 to 1935. Edited by Fritz J. Raddatz. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1989, ISBN 3-498-06496-7 .

- Sudelbuch . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1993, ISBN 3-498-06506-8 .

Film adaptations (selection)

Some films were made after his death based on Tucholsky's works. The most well-known are:

- 1963: Gripsholm Castle , by Kurt Hoffmann based on a script by Herbert Reinecker , with Walter Giller and Nadja Tiller , among others .

- 1967: Rheinsberg , by Kurt Hoffmann based on the script by Herbert Reinecker , with Cornelia Froboess and Christian Wolff .

- 1969: Christopher Columbus or The Discovery of America with Karl-Michael Vogler , Hans Clarin and Hannelore Elsner .

- 2000: Gripsholm , to Gripsholm Castle , by Xavier Koller , with Heike Makatsch , Ulrich Noethen .

documentary

- The roaring twenties - Berlin and Tucholsky. Documentary with game scenes and archive footage, Germany, 2015, 52:00 min., Script and director: Christoph Weinert, production: C-Films, NDR , arte , series: Die wilden Zwanziger , first broadcast: January 11, 2015 on SRF 1 , summary from ARD , online video , with Bruno Cathomas as Tucholsky.

Radio plays and sound carriers (selection)

- 1964: Gripsholm Castle , adaptation: Horst Ulrich Wendler, director: Hans Knötzsch , with Fred Düren , Ursula Karusseit , Angelica Domröse and others, radio of the GDR

- 1973: Gripsholm Castle - a summer story , adaptation: Horst Ulrich Wendler, music: Wolfgang Bayer, director: Hanns Anselm Perten , with Ralph Borgwardt, Ursula Figelius, Hans Rohde, Tina van Santen, long-playing record, Litera 860 067, VEB Deutsche Schallplatten Berlin GDR , as an audio book by BMG Wort 2001, ISBN 3-89830-137-0 .

- 1982: Lottchen is rehabilitated , Lottchen confesses 1 lover , Lottchen regrets , Lottchen visits a tragic film , short radio play series: Adaptation: Matthias Thalheim, Director: Achim Scholz, with Jutta Wachowiak , Klaus Piontek , Broadcasting Company of the GDR.

- 1985: Rheinsberg , arrangement: Matthias Thalheim, music: Thomas Natschinski , direction: Barbara Plensat , with Kurt Böwe , Ulrike Krumbiegel , Gunter Schoß , Dagmar Manzel and others, radio of the GDR; The Audio Verlag 2001, ISBN 3-89813-158-0 , reprint 2012, ISBN 978-3-86231-157-6 .

- 1985: You gave me wrong birth , biographical radio play by Irene Knoll, director: Wolfgang Schonendorf , Rundfunk der DDR

- 1990: All power goes out , success , afterlife , holes in the cheese , short radio play series, director: Christian Gebert, hr

- 1992: Christoph Columbus or The Discovery of America , directed by Gottfried von Eine with Kurt Ackermann , Maud Ackermann , Matthias Fuchs , Gert Haucke , Ben Becker , Hans Paetsch , Ilja Richter and others, Radio Bremen

- 1992: Christoph Columbus or The Discovery of America , arrangement: Heidemarie Böwe , music: Mario Peters , direction: Walter Niklaus with Eberhard Esche , Annekathrin Bürger , Hans-Joachim Hegewald , Otto Mellies , Martin Seifert , Rolf Hoppe and others, MDR

- 2014: Yes, Das Möchste , speaker: Katharina Thalbach , Audiobuch Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 2014, ISBN 978-3-89964-782-2 .

- 2014: Gripsholm Castle , speaker: Manfred Zapatka , Argon Verlag, Munich 2014, 4 CDs + MP3 version, 4 hours 31 minutes, ISBN 978-3-8398-9193-3 .

Radio broadcasts

- Two paths, one goal: Kurt Tucholsky and Carl von Ossietzky 1932 - 1935. Radio feature , BR Germany, 1985, 56 min., Manuscript: Elke Suhr, speakers: Wolf-Dietrich Berg , Hans-Helge Ott, production: Radio Bremen , Original broadcast: December 20, 1985, data set from Oldenburg University Library .

- Kurt Tucholsky - Learn to laugh without crying. Radio-Feature, Germany, 2014, 22:04 min., Manuscript: Brigitte Kohn, editor: radioWissen , production: Bayern 2 , first broadcast: April 29, 2014, audio file , manuscript and article .

Representation of Tucholsky in the visual arts (selection)

- Emil Stumpp: Kurt Tucholsky (chalk lithograph, 1929)

Literature (selection)

- Irmgard Ackermann (Ed.): Tucholsky today. Review and outlook . Iudicium, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-89129-091-8 , (with appreciations from Christoph Hein , Gert Heidenreich , Günter Kunert , Walter Jens and Eberhard Lämmert on the occasion of Tucholsky's 100th birthday).

- Klaus Bellin: It was like glass between us: the story of Mary and Kurt Tucholsky. Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86650-039-6 ; New edition, flap brochure, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-942476-19-5 .

- Helga Bemmann: I joined my club. Kurt Tucholsky as a chanson and song poet . Lied der Zeit Musikverlag, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-7332-0037-3 .

- Helga Bemmann: Kurt Tucholsky. A picture of life . Verlag der Nation, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-373-00393-8 ; Ullstein, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-548-35375-4 .

- Antje Bonitz, Thomas Wirtz: Kurt Tucholsky. A directory of his writings. Volume 1-3. (= German Literature Archive: Directories, Reports, Information , Volume 15). Marbach am Neckar 1991.

- Sabrina Ebitsch: The greatest experts in power. Concepts of power in Franz Kafka and Kurt Tucholsky . Tectum, Marburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-8288-2813-1 , ( dissertation from the University of Munich 2011, 310 pages), table of contents.

- Michael Hepp: Kurt Tucholsky. Biographical Approaches . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1993, 1999, ISBN 3-498-06495-9 .

- Michael Hepp: Kurt Tucholsky . Rowohlt Monographie, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1998, 2002, ISBN 3-499-50612-2 , (paperback with a short version of the above biography).

- Rolf Hosfeld : Tucholsky. A German life . Siedler, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-88680-974-5 .

- William John King: Kurt Tucholsky as a Political Publicist. A political biography. (= European University Papers , Series 1, German Language and Literature , Volume 579). Lang, Frankfurt am Main / Bern 1983, ISBN 3-8204-7166-9 , online file , registration required.

- Dieter Mayer: Kurt Tucholsky - Joseph Roth - Walter Mehring . Contributions to politics and culture between the world wars . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 978-3-631-60893-7 , online file , registration required.

- Fritz J. Raddatz : Tucholsky. A pseudonym . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1989, 1993, ISBN 3-499-13371-7 .

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki : Kurt Tucholsky - The nervous connoisseur. In: The Lawyers of Literature. dtv, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-423-12185-8 , pp. 217-226.

- Günther Rüther : We negatives. Kurt Tucholsky and the Weimar Republic . Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2018, ISBN 978-3-7374-1101-1 .

- Regina Scheer : Kurt Tucholsky. "It was a bit loud". Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938485-57-6 .

- Renke Siems: The Authorship of the Publicist. Writing and silence processes in the texts of Kurt Tucholsky . Synchron, Heidelberg 2004, ISBN 3-935025-34-3 , dissertation by Carl v. Ossietzky University of Oldenburg , online file.

- Richard von Soldenhoff (ed.): Kurt Tucholsky - 1890–1935. A picture of life . Quadriga, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-88679-138-6 .

- Gerhard Zwerenz : Kurt Tucholsky. Biography of a good German . Bertelsmann, Munich 1979; Goldmann, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-442-06885-1 .

Web links

Works by Kurt Tucholsky

- Literature by and about Kurt Tucholsky in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Kurt Tucholsky in the German Digital Library

- Inventory of: Kurt Tucholsky. In: German Literature Archive Marbach

- Kurt Tucholsky Archive in the Archive of the Academy of Arts, Berlin

- Works by Kurt Tucholsky at Zeno.org .

- Works by Kurt Tucholsky in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Kurt Tucholsky in the Internet Archive

- Works by and about Kurt Tucholsky at Open Library

- Works by Kurt Tucholsky at textlog.de

- Handwritten Vita Tucholsky 1934

- Free audio books with poems and texts by Tucholsky

- Sudelblog.de - The weblog about Kurt Tucholsky

About Kurt Tucholsky

- Kurt Tucholsky Society - biography, bibliography and texts

- Xlibris: life and work of Kurt Tucholsky - biography, interpretations, short contents, bibliography

- CV, collection of his works, background information. In: Kurt-Tucholsky.info

- Sonja Kock, Janca Imwolde: Kurt Tucholsky. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Kurt Tucholsky in: Who's Who

- Collection of links to Tucholsky texts In: tucholsky.org

- Kurt Tucholsky (Italian) at ti.ch/can/oltreconfiniti (accessed on: August 3, 2016.)

- Link collection ( memento from April 27, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) of the University Library of the Free University of Berlin

items

- Christoph Schottes: Tucholsky and Ossietzky after 1933. (PDF; source ), ISBN 3-8142-0587-1 .

- Erich Kuby : No Tucholsky today , 1989, ISBN 3-446-15043-9 , (Tucholsky reception in post-war Germany)

- Herbert Riehl-Heyse : “You can't shoot that deep”. In: SZ , May 17, 2010, SZ series: Great journalists

Exhibitions

- Kurt Tucholsky Literature Museum in Rheinsberg Castle

- 70th anniversary of Kurt Tucholsky's death. In: Bundesarchiv , 2005, virtual exhibition of manuscripts

- Catalog of an exhibition with many original documents. In: Kurt Tucholsky Society , 2005/06, (PDF; 4 MB)

- Kurt Tucholsky: Never again war! Messages of Pacifism , 2013, Internet exhibition on his 123rd birthday.

Radio broadcasts

- Brigitte Kohn: Kurt Tucholsky - Learn to laugh without crying. In: radioWissen , Bayern 2 from April 29, 2014, 10:04 min.

- Monika Buschey : January 9th, 1890 - birthday of the writer Kurt Tucholsky. In: WDR ZeitZeichen from January 9, 2015, 14:47 min.

- Kurt Tucholsky Podcast. Weekly audio pieces of texts that were published 100 years ago (since 1919).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Conversation with Peter Böthig in Mitteldeutsche Zeitung , December 20, 2005: Interview «Tucholsky had wanted his death» viewed October 20, 2020.

- ^ Klaus-Peter Schulz : Kurt Tucholsky with self-testimonies and photo documents. rororo, Reinbek 1992, especially pp. 64-74.

- ^ Great find in the historical library of the Thuringian Higher Regional Court - Kurt Tucholsky's doctoral thesis. ( Memento from June 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ). In: Thuringian Higher Regional Court , Media Information No. 05/2011.

- ↑ Helmut Herbst: Profiled. To the Marbach Tucholsky exhibition. In: Karl H. Pressler (Ed.): From the Antiquariat. Volume 8, 1990 (= Börsenblatt für den Deutschen Buchhandel - Frankfurter Ausgabe. No. 70, August 31, 1990), pp. A 334 - A 340, here: p. A 336.

- ↑ Kurt Tucholsky's personal vita for the application for naturalization in order to obtain Swedish citizenship, Hindås, 22.1.34 in: textlog.de .

- ↑ What is meant is the exercise book on arithmetic and algebra by the Rostock high school teacher Eduard Wrobel .

- ↑ Helmut Herbst: Profiled. To the Marbach Tucholsky exhibition. In: Karl H. Pressler (Ed.): From the Antiquariat. Volume 8, 1990 (= Börsenblatt für den Deutschen Buchhandel - Frankfurter Ausgabe. No. 70, August 31, 1990), pp. A 334 - A 340, here: p. A 336.

- ↑ Helmut Herbst: Profiled. To the Marbach Tucholsky exhibition. In: Karl H. Pressler (Ed.): From the Antiquariat. Volume 8, 1990 (= Börsenblatt für den Deutschen Buchhandel - Frankfurter Ausgabe. No. 70, August 31, 1990), pp. A 334 - A 340, here: p. A 336.

- ↑ Eric Saunier: Encyclopédie de la Franc-Maçonnerie. In: Humanität, ISSN 0721-8990 , 1985, No. 7, p. 8ff .; 2000, pp. 867f.

- ↑ Kurt Tucholsky, Our unlived life. Letters to Mary , Reinbek 1982, p. 537.

- ↑ Erich Kästner : Kurt Tucholsky, Carl v. Ossietzky, 'Weltbühne'. In: Die Weltbühne , June 4, 1946, p. 22.

- ↑ Michael Hepp: Kurt Tucholsky. Biographical Approaches. 1993, pp. 369–374 and 567. Similar: Rolf Hosfeld: Tucholsky - Ein deutsches Leben. 2012, p. 271, there also a reference to the missing farewell letter.

- ↑ Ignaz Wrobel: Requiem. In: Die Weltbühne , June 21, 1923, p. 732.

- ^ German Literature Archive Marbach : Information about the holdings of the DLA on Kurt Tucholsky's estate. In: dla-marbach.de , accessed on February 3, 2020.

- ^ Theobald Tiger: Eight years ago. In: Die Weltbühne, November 16, 1926, p. 789.

- ↑ Peter Panter: The sorted out. In: The world stage. January 13, 1931, p. 59.

- ↑ Oliver Pfohlmann: literary criticism in the Weimar Republic. In: Thomas Anz , Rainer Baasner (Hrsg.): Literary criticism. History - theory - practice. 5th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 114.

- ↑ Peter Panter: The trial. In: The world stage. March 9, 1926, p. 383.

- ↑ Peter Panter: Ulysses. In: The world stage. November 22, 1927, p. 793.

- ↑ Speech by Gershom Scholem at the fifth plenary session of the World Jewish Congress, in: Deutsche und Juden . Frankfurt am Main 1967, p. 39.

- ↑ Helmut Herbst: Profiled. To the Marbach Tucholsky exhibition. In: Karl H. Pressler (Ed.): From the Antiquariat. Volume 8, 1990 (= Börsenblatt für den Deutschen Buchhandel - Frankfurter Ausgabe. No. 70, August 31, 1990), pp. A 334 - A 340, here: p. A 335.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz : Kurt Tucholsky In: ders. (Ed.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus . Vol. 8 (supplements and register), 2015, p. 134 ff.

- ↑ Emil Stumpp : Over my heads . Ed .: Kurt Schwaen . Buchverlag der Morgen , Berlin, 1983, p. 14, 210

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tucholsky, Kurt |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hauser, Kaspar (pseudonym); Panter, Peter (pseudonym); Tiger, Theobald (pseudonym); Wrobel, Ignaz (pseudonym) |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | German journalist and writer |

| BIRTH DATE | January 9, 1890 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Berlin |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 21, 1935 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Gothenburg |