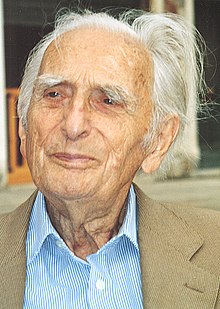

Erich Kuby

Erich Kuby , pseudonym Alexander Parlach (born June 28, 1910 in Baden-Baden , † September 10, 2005 in Venice ) was a German journalist and publicist .

Life

The early years

Kuby's father had bought an estate in West Prussia in 1901 , which he had to give up after only a year. He then moved to Munich and met his wife Dora Susskind there. Son Erich was born in Baden-Baden in 1910.

In 1913 the family moved to the Upper Bavarian Alpine foothills , where the father again took over a farm. There the child grew up, while the father as a reserve officer in the First World War served. After the end of the war, the family moved to Weilheim , where Kuby attended high school. Due to the long absence, his father seemed like "a rather strange gentleman",

"[...] from whom I learned that we had not lost the war, which I no longer believed, but rather began early on to develop into the black sheep of the family, a son who showed little interest than his father After moving to the next district town - where he bought and ran a much smaller farm - built a paramilitary organization at the local level, called the Resident Guard, whose teams held shooting festivals in the nearby 'shooting range', which were actually target practice, and one day his father even walked up and down with Ludendorff in our orchard, shortly before the Hitler putsch in November 1923 [...] "

Kuby received violin lessons in Munich . At school he was politically influenced by a critical Jewish teacher. He obtained his Abitur as an external student in Munich. He studied economics in Erlangen and Hamburg . He completed his studies in 1933 with a diploma. During the semester break he worked as a shipyard worker at Blohm & Voss in Hamburg.

In 1933 he followed his Jewish friend Ruth by bike and emigrated to Yugoslavia . From there, however, he returned to Germany on his own after a few months, because he supposedly wanted to analyze the “process of decay” in the country from close by, but from an inner distance.

After moving from Munich to Berlin, he worked in the picture archive of the Scherl publishing house . In 1938 he married the sculptor Edith Schumacher, the daughter of the Berlin economist Hermann Schumacher . The marriage had five children. His wife's sister was married to Werner Heisenberg . They were "nothing but patriots," as the title of the 1996 family story is. During the Second World War , Kuby served in the Wehrmacht in France and on the Eastern Front . In 1941, Kuby was sentenced to prison by a military court in Russia for an alleged security offense and demoted from corporal to ordinary soldier. He recorded daily life in the war and the stressful events in writing and also made a large number of drawings. After the end of the war he was only briefly in US captivity until June 1945. He later published his experiences in the war in the works Demidoff - or von der Inveruldlichkeit des Menschen (1947), Nur noch Rauchende Trümmer (1959) and Mein Krieg (1975) and published them many years later as a complete edition (published in 2000).

Journalistic career

After the end of the Second World War, Kuby first built up his destroyed parental home in Weilheim. The American military authority ICD ( Information Control Division ) in Munich then recruited him as a consultant. Kuby was commissioned by the American military administration to issue newspaper licenses for trustworthy personalities. Since January 1946 he was involved in the founding of the magazine Der Ruf , whose editor-in-chief he took over after Alfred Andersch and Hans Werner Richter were fired in 1947. Kuby did not fare any better in this role either, and he had to resign after a year. However, he stuck to his journalistic career because he did not set up his own publishing house. In the years that followed, Heinrich Böll ( Heinrich Böll ) worked as an editor for the Süddeutsche Zeitung . He then worked as a freelancer for Spiegel , Stern and Frankfurter Hefte , among others . In his articles he took a left-liberal position and was an important voice against German rearmament and plans for nuclear armament .

Kuby was considered one of the most important chroniclers in the Federal Republic of Germany. He was involved in the student movement in the mid-1960s. In the summer semester of 1965, the Kuby case made headlines nationwide when he was banned from speaking by the then rector of the Free University of Berlin . Seven years earlier, Kuby had been critical of the name “Free University” and was therefore not allowed to accept the AStA's invitation to a panel discussion, which then led to massive counter-protests from the student body.

In 1965 Kuby wrote the six-part series “The Russians in Berlin 1945” for Spiegel magazine and then expanded the sources known at the time, which were also accessible in Eastern Europe, to create a volume of the same name.

In 1983 and 1987, respectively, he carried out detailed critical analyzes for the magazines Stern and Spiegel . With his war diary Mein Krieg. In 1975, Kuby presented an interior view of the Wehrmacht with records from 2129 days , which, however, was not a sales success in the first edition.

Radio plays and scripts

In addition to his journalistic work, he adapted socially critical material for radio and television. A radio play about what, in his opinion, was senseless defense of the fortress of Brest by the Wehrmacht , brought him a lawsuit for insult by the responsible general Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke . Kuby had witnessed the destruction of Brest in 1944 as a soldier. The suit was dismissed in 1959.

Kuby became famous for his work on the screenplay for the film Das Mädchen Rosemarie , which he used as a template for his novel Rosemarie in 1958 . The German miracle's dearest child served. The unexplained murder of the Frankfurt noble prostitute Rosemarie Nitribitt formed the framework for a drama that outlined the time of the economic miracle as characterized by double standards. Kuby's fictional portrayal captured the zeitgeist of the time so realistically that his hypothetical version of the background to the murder was largely adopted by the public. Even small dramaturgical details, such as Nitribitt's allegedly red sports convertible, the legendary Mercedes-Benz 190 SL , can be found in many representations today as assertions of fact. The so-called Nitribitt Roadster actually existed, but in the reporting at the time it was described as black.

Last years

Kuby spent most of the last 25 years of his life in Venice , from where he continued to participate in current political debates in Germany. Until 2003, the “Homme de lettres” wrote the column “Der Zeitungsleser” regularly for the weekly newspaper Freitag . Erich Kuby died at the age of 95 and is buried on the cemetery island of San Michele in Venice.

family

Erich Kuby was married twice. The children Thomas, Gabriele , Clemens and Benedikt come from his first marriage with Edith Schumacher (1910–2001) - daughter of Hermann Schumacher (professor, privy councilor and economist) . The last three named are also active as a journalist. Then he was married to the literary scholar , author and journalist Susanna Böhme-Kuby (* 1947), with whom he had their son Daniel. The conservative Catholic activist Sophia Kuby , formerly spokeswoman for the media network “Generation Benedikt”, is a granddaughter (daughter of Gabriele).

Awards

For his life's work as a journalist, Kuby was awarded the Journalism Prize of the City of Munich in 1992 . The laudation was given by Wolfgang R. Langenbucher . Posthumously , Kuby was awarded the Kurt Tucholsky Prize in 2005. Heinrich Senfft gave the laudation .

Filmography (selection)

- 1959: The man who sold himself

Works (selection)

- (1947): Demidoff or of the inviolability of people , by Erich Kuby under the pseudonym Alexander Parlach, Paul List Verlag, Munich 1947

- (1956): The End of Terror: Documents of Downfall January to May 1945 , Süddeutscher Verlag, Munich 1956

- (1957): That is the German fatherland - 70 million in two waiting rooms. Stuttgart: Scherz & Goverts, 485 pp.

- (1958): Rosemarie. The dearest child of the German miracle. Stuttgart: Goverts, 306 pages, reprint: Rotbuch Verlag, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86789-119-6

- (1959): Only smoking debris left. The end of the Brest fortress. Diary of the soldier Erich Kuby; with text of the audio image, pleading by the public prosecutor, justification of the judgment. Hamburg: Rowohlt, 198 pp.

- (1962): Im Fibag-Wahn or His friend the Minister. Hamburg: Rowohlt, 127 pp.

- (1963): Franz Josef Strauss : A Type of Our Time. [Employees]: Eugen Kogon , Otto von Loewenstern, Jürgen Seifert. Vienna: Desch, 380 pp.

- (1963): Richard Wagner & Co. on the 150th birthday of the master. Hamburg: Nannen, 155 pp.

- (1965): The Russians in Berlin 1945. Scherz Verlag, Munich Bern Vienna 1965

- (1968): Prague and the Left. Hamburg: Konkret-Verlag, 154 S., Ill.

- (1975): My War. Records from 2129 days. Nymphenburger, Munich, ISBN 3-485-00250-X . Several new editions, most recently as a paperback structure 1999 ISBN 3-7466-1588-7 . Review by Florian Felix Weyh in the “Büchermarkt” of Deutschlandfunk , April 20, 1999, [1] .

- (1982): Treason in German. How the Third Reich ruined Italy. [Trans. from d. Ital. u. Engl .: Susanna Böhme]. Hamburg: Hoffmann and Campe, 575 pp. ISBN 3-455-08754-X

- (1983): The Stern Case and the Consequences. Hamburg: Konkret Literatur Verlag, 207 pp. ISBN 3-922144-33-0 and Berlin: Volk und Welt, 206 pp.

- (1986): When Poland was German: 1939–1945. Ismaning near Munich: Hueber, 341 pp.

- (1987): The mirror in the mirror. The German news magazine ; critically analyzed by Erich Kuby. Munich: Heyne, 176 pp. ISBN 3-453-00037-4

- (1989): My angry fatherland. Munich: Hanser, 560 pp., Linen, ISBN 3-446-15043-9 .

- (1990): The Price of Unity. A German Europe shapes its face. Hamburg: Konkret Literatur Verlag, 112 pp. ISBN 3-922144-99-3

- (1990): Germany: from indebted division to undeserved unity. Rastatt: Moewig, 398 pp.

- (1991): German Perspectives. Unfriendly side notes. Hamburg: Konkret Literatur, 160 pp. ISBN 3-89458-105-0

- (1996): The Newspaper Reader. In weekly steps through the political landscape 1993–1995. Hamburg: Konkret Literatur, 160 pp. ISBN 3-89458-145-X

- (1996): Lots of patriots. A German family story. Munich: Hanser, b. ISBN 3-446-15918-5

- (2010): Erich Kuby on the 100th recordings 1939–1945. Hamburg: hyperzine verlag, catalog for the traveling exhibition of drawings and watercolors, curated by Susanne Böhme-Kuby and Benedikt Kuby, 100 pp. ISBN 978-3-938218-16-7

- (2020): Rosemarie. The dearest child of the German miracle . With an essay by Jürgen Kaube . Schöffling & Co., Frankfurt am Main 2020, ISBN 978-3-89561-028-8

Quote

- Publishers sip their champagne from journalists' brains.

Web links

- Literature by and about Erich Kuby in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Erich Kuby in the German Digital Library

- Erich Kuby in the Bavarian literature portal (project of the Bavarian State Library )

- Erich Kuby in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Short biography of the Tucholsky Prize winner and a selection of three texts

- The Erich Kuby Source Page

Individual evidence

- ^ Die Zeit May 21, 1965 How free is the Free University? His magnificence forbids Erich Kuby to speak.

-

↑ Erich Kuby: The Russians in Berlin 1945 . In: Der Spiegel . No. 19 , 1965, p. 74-92 ( Online - May 5, 1965 ). Erich Kuby: The Russians in Berlin 1945. 1. Continuation . In: Der Spiegel . No.

20 , 1965, p. 74-94 ( Online - May 12, 1965 ). Erich Kuby: The Russians in Berlin 1945. 2. Continuation . In: Der Spiegel . No.

21 , 1965, p. 57-74 ( Online - May 19, 1965 ). Erich Kuby: The Russians in Berlin 1945. 3. Continuation . In: Der Spiegel . No.

22 , 1965, p. 94-113 ( Online - May 26, 1965 ). Erich Kuby: The Russians in Berlin 1945. 4. Continuation . In: Der Spiegel . No.

23 , 1965, p. 69-86 ( online - June 2, 1965 ). Erich Kuby: The Russians in Berlin 1945. 5. Continuation and conclusion . In: Der Spiegel . No.

24 , 1965, pp. 78-89 ( online - June 9, 1965 ). - ^ Kuby, Erich: The Russians in Berlin 1945 . Scherz Verlag, Munich Bern Vienna 1965

- ↑ http://www.muenchen.de/Rathaus/kult/kulturfoerderung/preise/publizistikpreis/158905/preistraeger.html

- ^ Laudatory speech by Heinrich Senfft

- ^ New edition: My angry fatherland. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 2010. See Jan Scheper: Bittere Truths. taz.de, June 28, 2010.

- ↑ dradio.de, September 12, 2005

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kuby, Erich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Parlach, Alexander (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German journalist and publicist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 28, 1910 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Baden-Baden , Germany |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 10, 2005 |

| Place of death | Venice , Italy |