World stage process

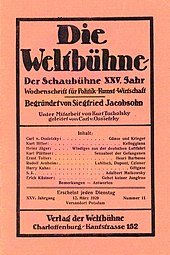

The Weltbühne trial (often also known as the Weltbühne trial ) was one of the most spectacular criminal proceedings against military-critical press organs and journalists in the Weimar Republic . In the process, the editor of the weekly newspaper Die Weltbühne , Carl von Ossietzky , and the journalist Walter Kreiser were charged with treason and betrayal of military secrets and were sentenced in November 1931 to 18 months ' imprisonment by the fourth criminal division of the Reichsgericht in Leipzig .

Because of the controversial issue of the secret establishment of a German air force and the intended attack on freedom of the press with indictment and judgment , the trial attracted a great deal of attention at home and abroad. A resumption of the proceedings before the Federal German courts failed in 1992. The process is considered a prime example of political justice in the Weimar Republic.

prehistory

Treaty of Versailles

After the defeat in the First World War , the German Reich had to consent to a severe restriction of its military forces with the Treaty of Versailles . Despite the signature, the Reich government and the Reichswehr systematically tried to undermine the provisions of the treaty. Above all, they tried from the beginning to circumvent the limitation of the German army to a maximum strength of 100,000 men set out in Article 163. Influential circles of the Reich governments and the Reichswehr secretly supported the establishment of paramilitary groups and set up illegal arsenals.

These paramilitary groups, which emerged from the Freikorps in the immediate post-war period and were also known as the Black Reichswehr , were a constant source of uncertainty in German domestic politics. In some cases they created unlawful spaces in which violent crimes against dissenters and apostate members were tolerated.

Pacifist and anti-militarist circles in the Weimar Republic therefore saw the behavior of the Reichswehr as a threat to internal peace and to the consolidation of foreign policy in the German Reich. Various publications drew attention to the grievances. A publication by Weltbühne about the femicide in the Black Reichswehr ultimately led to several criminal proceedings against the perpetrators. From the beginning of the Weimar Republic, however, the legal processing of these crimes was made difficult by extreme partisanship for the perpetrators. For example, the Reichsgericht admitted in favor of the fememicide “that there is also a right of individual citizens to defend themselves against illegal attacks on the vital interests of the state” ( RGSt 63, 215 (220)). In return, pacifists who betrayed the illegal weapons caches were sentenced to 10 to 15 years in prison for treason.

Military critical press

The media, which drew attention to the grievances, were also subjected to severe repression. The journalists Berthold Jacob and Fritz Küster , for example, were convicted of “journalistic treason” in the “ pontoon trial ” in 1928 because they had uncovered the system of temporary volunteers. These soldiers were called in for short-term military exercises and did not appear in any statistics. In its judgment against Jacob and Küster, the Reichsgericht came to the following view: The idea should be rejected, “that the disclosure and disclosure of illegal conditions can never be detrimental to the Reichswell, only beneficial because the welfare of the state is laid down in its legal system and is in realize their implementation "(RGSt 62, 65 (67)). In addition, the Reichsgericht demanded: “Every citizen has to remain loyal to his own state. To look after the well-being of his own state is the highest commandment for him ”. From this perspective, it is not surprising that in the years 1924 to 1927 alone, more than 1,000 people were convicted of treason, insulting the Reichswehr and similar offenses. A passage from a treatise on treason in German criminal law shows how much legal theory identified with politics on this issue :

“If one points to the large number of trials of treason after the war compared to those in peacetime, the answer to this is that the number of these trials will not decrease as long as the shameful Treaty of Versailles, which was imposed on us, is still valid deliberately contains such ingenious provisions that even with the best will of ours cannot be met down to the smallest detail, which in the end is also intended by the Entente in order to make us feel the whip of joy all the time, and on the other hand as long as there will be Germans who humiliate themselves to the bailiff of the Entente, even consciously confess to it, because to them the fulfillment of the indignant peace provisions seems more important than the welfare of the fatherland. "

However, the provisions of the Versailles Treaty not only limited the strength of the army. In Article 198, they also expressly forbade the establishment of an air force. In pacifist circles, however, it was known that this provision was also circumvented. For example, Berthold Jacob criticized the lack of transparency in the ranking of the German Imperial Army ,

"Because a number of the actually existing departments of the Reichswehr Ministry , such as aviation, gas combat preparation, the counter-espionage and espionage departments and many others, do not officially appear at all."

One of the journalists who dealt particularly intensively with the secret development of the German Air Force was the aircraft designer Walter Kreiser . In a letter from August 1925, Kreiser described himself as "the only one in pacifist circles who has a precise insight into aviation". That is why he had already published seven articles on aviation in the world stage under the pseudonym Konrad Widerhold . Because of his participation in the work The German military policy since 1918 , proceedings against him for treason and betrayal of military secrets had already been initiated in 1926, but these were discontinued in 1928 . At the beginning of 1929 Kreiser finally offered the Weltbühne a new article, the publication of which he expected a great response. This is also evident from a letter from Kreiser dated March 4, 1929 to Ossietzky, which was later assessed by the court as incriminating against the defendants. It said:

“It is appropriate to bring the essay in the world stage on March 11th. On this day at 8 o'clock in the evening an aviation meeting called by the WGL takes place in the manor house, where all the celebrities of aviation and those who want to be can be found. Perhaps you will order a capable newspaper seller there, he will certainly get rid of a few hundred copies, since the article should look like a bomb on this particular gathering. "

The incriminated article

Against the background described, it is not surprising that the article “Windy things from German aviation”, published on March 12, 1929 in the Weltbühne under the pseudonym Heinz Jäger, aroused the displeasure of the Reichswehr. In the extensive, five-and- a-half-page article, Kreiser first dealt with general questions about the situation in German aviation , before finally devoting the last one and a half pages to the connections between the Reichswehr and the aviation industry. From this section it emerged that the Reichswehr was evidently operating the secret establishment of an air force, circumventing the Versailles Treaty . Under the heading "Department M", Kreiser wrote:

“Similar capers were made at the Johannisthal -Adlershof airfield . On the Adlershof side, there was a so-called Department M as a special group of the German Research Institute for Aviation . When the socialist MP Krüger in the budget committee asked the government representatives for information about the purpose of Department M, he got no answer, because otherwise should have made the authorities aware that 'M' is also the first letter of the word military. So it was better to be silent. But here too, Gröner's resourceful fogging tactics are at work. In order to be able to say in the case of a renewed inquiry: there is no longer such a department M, we have cleared up these messes, this department was also disbanded, came to the Johannisthaler side of the airfield and is now called 'Albatros testing department', in contrast to one Research department that Albatros already owns. This 'Albatros testing department' is the same on land what the 'coastal flight department of Lufthansa' is on the sea. Both departments have about thirty to forty aircraft each, sometimes more.

But not all aircraft are always in Germany ... "

The manuscript is also said to have stated that the aircraft were temporarily in Russia . As a precaution, Ossietzky had deleted these passages and confined himself to hinting at them. With his statements, Kreiser referred in part to the minutes of the 312nd meeting of the Committee on the Reich Budget of February 3, 1928. Although these minutes were available as printed matter, the Oberreichsanwalt initiated investigations into violations of the treason section of the Reich Criminal Code and Section 1, Paragraph 2 of the law against the betrayal of military secrets (the so-called espionage law of June 3, 1914, RGBl , 195).

Procedure

On August 1, 1929, a criminal complaint was finally filed. In a letter dated August 8, 1929, the senior Reich attorney informed the Prussian Minister of the Interior that a preliminary investigation had been initiated into the incriminated article. The reason given was that Ossietzky and Kreiser,

"Have made public news of which they knew that their secrecy from another government is necessary for the good of the German Reich, as well as deliberately news to a foreign government or to a person, the secrecy of which is necessary in the interests of national defense that is active in the interests of a foreign government, and thereby endangered the security of the Reich. "

In the course of the investigation, the editorial offices of the Weltbühne and Ossietzky's apartment were searched. In August 1929, Ossietzky was also questioned on the case. The fact that the negotiations did not subsequently take place is attributed to the political implications described below.

Political Implications

The Reich government found itself in a dilemma after the article was published. If she had ignored the article or simply denied it, she would have run the risk of further details of the secret rearmament efforts having leaked to the public. However, cracking down on the author and editor was tantamount to admitting that the German Reich had actually violated the provisions of Versailles and was secretly building an air force. The interests of the Reichswehr Ministry and the Foreign Office therefore clashed very strongly.

As the further course of the process showed, the military interests were rated more important than the foreign policy damage that would result from a conviction of the journalists. The evaluation of Soviet archives showed that the publication of the article had also been noticed in Moscow .

“In the second half of 1929 the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Russia (Bolsheviks) discussed relations with the Reichswehr in the Kremlin . Under point 1a of the minutes of the resolution it can be read that the German side 'demanded the strengthening of the conspiracy in the cooperation between the two armies as well as guarantees that no information whatsoever relating to this cooperation will be published in future'. "

The Reichswehr Ministry had to be very concerned not to endanger the important military cooperation with the Soviet Union. The Foreign Office, on the other hand, had to consider the negotiating position of the Reich in the Geneva disarmament negotiations as threatened by a public court hearing. How important the office took to the process is also shown by the fact that the documents collected filled several volumes of files in the legal department. The fact that the start of the process was delayed for so long is attributed to the resistance of the Foreign Ministry, which until October 1929 was still led by Gustav Stresemann . There, with a view to the above-mentioned minutes of the Reichstag, the question was raised whether the information from the article was actually secret.

However, the proceedings were not ended. In the spring of 1931, the three ministries involved finally agreed on a compromise in order to be able to open legal proceedings . More than two years after the article appeared, on March 30, 1931, charges were brought.

Legal Actors

On the part of the public prosecutor's office and the Reichsgericht, the world stage had to deal with lawyers who had already gained notoriety. Reich attorney Paul Jorns , under whose direction the indictment against Ossietzky was drawn up, was involved in the investigation into the murders of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg and had covered up traces there. The chairman of the IV Criminal Senate, Alexander Baumgarten , had headed the Ulm Reichswehr trial in the autumn of 1930 , during which Adolf Hitler had made his “declaration of legality” but also announced that “heads would roll” after he took office.

The defendants were defended by the renowned lawyers Max Alsberg , Kurt Rosenfeld , Alfred Apfel and Rudolf Olden . Since the defense was convinced of a successful outcome of the trial, von Ossietzky had also refrained from filing an application for rejection against the IV Criminal Senate. "For years I had written that the IV Criminal Senate did not speak the law of the German Republic, but that it had accepted the practice of a court martial," said von Ossietzky, explaining his mistrust of the court.

negotiation

The legal regulations according to § 174 Abs. 2 GVG forbade the Weltbühne to report in detail about the process (and would even forbid it today). For reasons of state security, the public was excluded from the negotiations anyway. Those involved in the process were also obliged to maintain secrecy, which later also affected the reasons for the judgment. On May 5, 1931, the magazine's readers finally found out about the process, which had been pending for two years. The trial was to begin on May 8, 1931.

The negotiations were immediately postponed because no representative from the Foreign Ministry had appeared. The defense had insisted that in addition to the Ministry of Defense, the Foreign Office should also send an expert. This was supposed to answer the question of whether the article actually contained information that was unknown abroad. However, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs canceled the trial and continued to have serious concerns about the foreign policy impact of the trial. Therefore, a month later, it refused to send an expert to Leipzig again. On July 9, 1931, General and later Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher wrote a letter to Bernhard Wilhelm von Bülow , State Secretary in the Foreign Office, and reprimanded his delaying tactics. Schleicher saw in the process a precedent to enforce the "most effective defense and the best prevention against treason". For this reason, the Federal Foreign Office should "resign" its political concerns and write an expert opinion. A few days later, Bülow replied that his ministry wanted to shape the “fight against treason” in such a way “as the interests of the Reich, in particular [...] national defense” require. Finally, on August 24, 1931, the office prepared a written report that was read out during the hearing.

The closed hearing finally took place on November 17 and 19, 1931. Major Himer from the Ministry of Defense and Ministerialrat Wegerdt from the Ministry of Transport acted as witnesses for the prosecution. They confirmed that the information from the article was true and should have been kept secret in the interests of national defense. Major Himer was convinced that the article had also been evaluated by foreign news agencies . However, he was unable to provide any proof of this.

The court denied all 19 defense witnesses. The central request for evidence was also not heard by the judges. In it the defense wanted to prove that the reported activities had been known abroad for a long time. Ossietzky himself argued on his own account that the article should only have criticized the budget. Most of the wording in the disputed section was due to him and was hardly understandable for the uninformed public. His aim was to warn the Reichswehr Ministry before the matter turned into a public scandal.

judgment

The trial ended on November 23rd with the conviction of the two defendants for "crimes against Section 1 (2) of the Law on the Disclosure of Military Secrets of June 3, 1914" to the prison sentence of 18 months required by the public prosecutor's office. The relevant edition of the Weltbühne from March 1929 "as well as the plates and molds necessary for their production" had to be rendered unusable. The reasoning for the judgment was also read out in camera, "since the factual and legal assessment of the incriminated article by the court naturally could not take place without considering and illuminating the secret news in question".

In its reasoning, the court argued that, according to the experts, the accused had actually distributed news that had to be kept secret. In this case the concept of secrecy is only a relative one. It is irrelevant whether the activities mentioned were already known within certain circles. As in the trial against Küster and Jacob, the court emphasized that the citizen had to remain loyal to his country and not be allowed to arbitrarily denounce the violation of international treaties. This is only possible by making use of national organs. The court justified the necessary resolution by stating that the defendants were pacifists. This justifies the conclusion that they wanted to act anti-military. Which "informally" resulted in their will to uncover something that was kept secret by the military administration.

According to the court, the fact that the conviction was not based on the state treason clause did not mean that the accused did not fulfill the relevant criminal offenses. Rather, the Reichsgericht was of the opinion that the more specific criminal offense of the Espionage Act replaced the also relevant state treason clause of the Criminal Code by way of legal competition . In the grounds of the judgment it said:

“In the legal assessment of the factual facts, it must be stated in advance that the criminal act of which the defendants are charged is only to be assessed from the point of view of the crime against the law against the betrayal of military secrets of June 3, 1914. Between this offense and that of treason according to Section 92 (1) (1) StGB, if the betrayal of military secrets is in question, there is unity of law; in this case, as the Senate assumes with the overwhelming opinion in the literature, the legal assessment only has to be made according to the more specific law, ie here the so-called Treason Act of June 3, 1914. "

Consequences of the judgment

Political reactions

Von Ossietzky reacted to the conviction with sarcasm. “A year and a half imprisonment? It's not that bad, because freedom in Germany isn't that far away. Gradually, the differences between people imprisoned and those not imprisoned are fading. ”The verdict did not surprise him, even if he did not consider the outcome of the trial to be conceivable:

“I know that every journalist who deals critically with the Reichswehr has to face treason proceedings; that is a natural occupational risk. Nevertheless, this time there was a delightful change: We did not leave the room as traitors, but as spies. "

Ossietzky was alluding to the fact that he was not convicted of treason, as requested by the public prosecutor. In later articles, Ossietzky refrained from emphasizing this difference, but chose a formulation that did more justice to the arguments of the Reichsgericht:

“As a precaution, the Reichsgericht stamped me in the most unpleasant way. Treason and betrayal of military secrets - that is a highly defamatory etiquette that is not easy to live with. "

The ruling caused a sensation at home and abroad for a number of reasons. The world stage in nos December 1 and December 15, 1931, numerous foreign press on the process whose tenor comes in the following passage expresses:

“First, it is the harshest judgment ever passed on a non-communist publicist, and it is typical of the rigorous treatment that German courts are now treating anyone who disagrees with a return to pre-war militarism in Germany. Second, one should assume that the government, or at least the Foreign Office, does not approve of this judgment, because it draws the public's attention to events that might otherwise have long been forgotten or overlooked. Germany, whose arguments before the Disarmament Commission always came down to the fact that the Versailles Treaty had been fulfilled and that it had completely disarmed, will now have to defend itself again against the charge that it maintains a banned air fleet. In the future, critics will rely less on the Weltbühne article than on the Reichsgericht, which considered this article so dangerous that it punished it with eighteen months in prison. There is no appeal and Ossietzky ... has to face this long sentence. It is characteristic of the tendency of German courts that National Socialist traitors are condemned more and more leniently, mostly with a fortress , while a liberal critic of militarism is locked up with common criminals. "

In Germany, too, many democratic politicians were appalled. Reichstag President Paul Löbe wrote: “I have seldom perceived a judgment as such a failure not only in legal but also in political terms as this [...] As far as I know, nothing has been written that could be hidden or useful to foreign countries, like that that the judgment seems completely incomprehensible to me. "

After the verdict, various organizations tried to prevent Ossietzky from actually serving the prison sentence. So the sent SPD - Reichstag an interpellation to the national government and asked whether this was not prepared to "do all steps to ensure the enforcement of that judgment to prevent the Imperial Court." There were protests and petitions of the German League for Human Rights . Many prominent writers and scientists such as Thomas Mann , Heinrich Mann , Arnold Zweig and Albert Einstein supported a petition for clemency to the Reich President Paul von Hindenburg , which was supposed to prevent the implementation of the judgment at the last minute. But the Ministry of Justice did not even forward the application to Hindenburg. So von Ossietzky finally started his sentence on May 10, 1932 in the prison in Berlin-Tegel. Walter Kreiser, on the other hand, left for France immediately after the verdict and thus evaded imprisonment. Instead, Ossietzky argued:

"There is one thing I do not want to be mistaken about, and I emphasize this for all friends and opponents and especially for those who have to look after my legal and physical well-being for the next eighteen months: - I do not go to jail for reasons of loyalty, but because I am the most uncomfortable as a prisoner. I do not bow to the majesty of the Reichsgericht, wrapped in red velvet, but as an inmate of a Prussian penal institution I remain a lively demonstration against a decision of the highest instance, which appears politically tendentious in the matter and which is a lot wrong as a legal work. "

Due to a Christmas amnesty for political prisoners, Ossietzky was released early on December 22, 1932 after 227 days in prison.

Legal assessment

The trial certainly meant one of the sharpest attacks by the Reichswehr and the judiciary against the critical press in the Weimar Republic. In this way it also became clear to other countries that Germany obviously no longer intended to observe important points of the Versailles Treaty. Even during his imprisonment in the concentration camp, Ossietzky should still feel the consequences of the conviction. In the dispute over the award of the Nobel Peace Prize , the argument against the concentration camp prisoner was that he was, after all, a convicted traitor.

Today's lawyers see the judgment as an important step on the way to Nazi justice. With the treason trials, the Reichsgericht established its own legal system, which was not based on laws and the constitution, but on unclear terms ("treason of the fatherland", "citizen's duty of loyalty", "state welfare").

"Reichsgerichtratsrat Niethammer confirmed his 'pacemaker' services for Nazi law, and the 'national' defender Alfons Sack praised the RG for the 'courageous step [...] against the letters of the constitution to help the new state idea to triumph', with which it made its contribution to the 'creation of the new law, for which the security of the German people alone is the yardstick'. In slightly different words, Ossietzky defense attorney Olden described the same thing: “This is where the rotting of the law and sense of justice comes from, which leads the Supreme Court to the National Socialist distortion of all legal terms, to the legitimation of murder if it only serves the 'public welfare'. ““

After his conviction, Ossietzky admitted that the republic had at least preserved “the decorum of legal proceedings”. "Once the Third Reich is governed according to the Boxheim platform , traitors like Kreiser and I will be fusilized without a fuss," he wrote on December 1, 1931 in the Weltbühne .

During the so-called Spiegel Affair , the press drew parallels with the Weltbühne process. For example, the Federal Court of Justice Senate President Heinrich Jagusch published the widely acclaimed article “Is there a new Ossietzky case threatened?” Under the pseudonym “Judex”. Disciplinary proceedings were then opened against Jagusch, which were only discontinued in August 1967 at the instigation of the Federal Minister of Justice at the time. The memory of the Weltbühne trial certainly contributed to the fact that the public in the Federal Republic did not want to accept a similar encroachment on the freedom of the press in this case . In the meantime, publication as in the case of the Weltbühne text would no longer be punishable anyway. Because in Section 93, Paragraph 2 of the Criminal Code, the following is added to the concept of state secret:

"Facts that violate the free democratic basic order or, in secrecy vis-à-vis the contracting parties of the Federal Republic of Germany, violate armaments restrictions agreed between states are not state secrets."

However, the betrayal of such illegal state secrets “by a foreign power or one of its middlemen” remains punishable under Section 97a of the Criminal Code. According to critics, there is a risk that this could be extended to press releases as well.

Retrial

In the 1980s, German lawyers tried to get the case back on track. This was intended to revise the 1931 judgment. Rosalinde von Ossietzky-Palm , Carl von Ossietzky's only child, initiated the proceedings on March 1, 1990 at the Berlin Court of Appeal . As new evidence, the reports of two experts were presented, which were supposed to show that the French army was already informed about the activities of the Reichswehr before the publication of the text. In addition, some of the “secrets” complained of were not factual. The Chamber Court declared a reopening of the proceedings inadmissible. The new reports are not sufficient as facts or evidence to acquit von Ossietzky under the law of the time. The explanatory memorandum of July 11, 1991 stated:

“The fact that foreign governments were informed about the secret rearmament of the German Reich justifies the vague assumption that they were also aware of the events uncovered in connection with the Johannisthal-Adlershof airfield before they were published. [...] For the opinion of the expert that the French military leadership was informed about every step of the German armament, including the facts communicated in the article, there is no comprehensible examination of the material used. "

The Federal Court of Justice then rejected a complaint against the decision of the Court of Appeal. He justified this in his decision of December 3, 1992:

“Incorrect application of the law in itself is not a reason for retrial under the Code of Criminal Procedure. With the exception of the case of the involvement of a dishonest judge, the `` no matter how wrong decision '' based on the wrong legal opinion can only be eliminated in the retrial if the facts on which the incorrect decision is based are incorrect. […] According to the rulings of the Reichsgericht, the illegality of the secret events did not exclude the secrecy. In the opinion of the Reichsgericht, every citizen owes his fatherland a duty of loyalty, stating that the endeavor to comply with the existing laws could only be realized by making use of the national organs appointed for this purpose and never by reporting to foreign governments. "

The Federal Court of Justice did not actually “confirm” the judgment of the Reichsgericht, but merely decided that no “new facts and evidence” within the meaning of Section 359 of the Code of Criminal Procedure were presented that would enable the deceased to be acquitted in accordance with Section 371 (1) of the Code of Criminal Procedure would have.

The decisions of the two courts were seen by critics as an indication that the Federal German judiciary is still struggling to come to terms with German legal history. The opinion of the Court of Appeal confirmed by the BGH, according to which “another expert as such is fundamentally not new evidence”, also violates the “unanimous commentary opinion” (Ivo Heiliger). The criticism of the BGH thus goes in the direction of the fact that the content of the new reports had already been rated too strongly in the decision on the admission of the retrial, instead of leaving this assessment to the retrial itself.

After Rosalinde von Ossietzky-Palm died in 2000, the public prosecutor's office is still entitled to apply for a new retrial. Therefore, the lawyers Gerhard Jungfer and Ingo Müller demand :

"After the BGH realized that not every Reich court judgment is worth preserving and the 5th Criminal Senate has already criticized the BGH's inadequate coming to terms with the past, it would be a nobile officium of the German judiciary to overturn the 70-year-old judgment and give the Nobel Prize winner - last but not least, to rehabilitate yourself. "

literature

swell

- The world stage. Complete reprint of the years 1918–1933. Athenäum Verlag , Königstein / Ts. 1978, ISBN 3-7610-9301-2 .

- Walter Bussmann et al. (Ed.): Files on German foreign policy. 1918-1945. Series B. 1925-1933. Volume 19, 16 October 1931 to 29 February 1932. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1983.

- Foreign Office: Secret files of the old legal department, case: criminal proceedings for treason against editor Carl von Ossietzky, volumes 1 and 2 (unpublished)

- Foreign Office: files of the legal department, secret cases, spec. Kreiser and Ossietzky, volumes 1–3 (unpublished)

- Kammergericht Berlin 1. Criminal Senate, decision of July 11, 1991, Az .: (1) 1 AR 356/90 (4/90), published in: Neue Juristische Wochenschrift (NJW). Beck, Munich / Frankfurt M 1991, pp. 2505-2507. ISSN 0341-1915

- BGH 3rd Criminal Senate, decision of December 3, 1992, Az .: StB 6/92, published in: BGHSt 39, pp. 75–87.

- Carl von Ossietzky : All writings. Published by Bärbel Boldt et al. Volume VII: Letters and Life Documents. Reinbek 1994.

Secondary literature

Monographs

- Bruno Frei : Carl von Ossietzky - a political biography. Das Arsenal, Berlin 1978, ISBN 3-921810-15-9 .

- Heinrich Hannover : The Republic in Court 1975–1995. Memories of an uncomfortable lawyer. Aufbau-Taschenbuch-Verl., Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-7466-7032-2 .

- Ursula Madrasch-Groschopp: The world stage. Portrait of a magazine. Book publisher Der Morgen, Berlin 1983, Bechtermünz im Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1999 (reprint), ISBN 3-7610-8269-X .

- Dieter Lang: State, law and justice in the commentary of the magazine "Die Weltbühne". P. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-631-30376-9 .

- Elke Suhr: Carl von Ossietzky. A biography. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-462-01885-X .

- Hermann Vinke : Carl von Ossietzky. Dressler, Hamburg 1978, ISBN 3-7915-5007-1 .

Essays

- Gerhard Jungfer, Ingo Müller : 70 years of the Weltbühnen judgment. In: Neue Juristische Wochenschrift (NJW). Beck, Munich / Frankfurt M 2001, pp. 3461-3465. ISSN 0341-1915

- Ivo Heiliger ( pseudonym of Ingo Müller ): A second misjudgment against Ossietzky. In: Critical Justice (KJ). Nomos, Baden-Baden 1991, pp. 498-500. ISSN 0023-4834

- Ivo Heiliger ( pseudonym of Ingo Müller ): Windy things from German jurisprudence. In: Critical Justice (KJ). Nomos, Baden-Baden 1993, pp. 194-198. ISSN 0023-4834

- Ingo Müller : The famous Ossietzky case from 1930 could be repeated at any time ... In: Recht Justiz Critique, Festschrift for Richard Schmid, ed. by Hans-Ernst Bötcher. Nomos, Baden-Baden 1985, ISBN 3-7890-1092-8 , pp. 297-326.

- Elke Suhr: "On the background of the 'world stage' process." In: Alone with the word. Erich Mühsam, Carl von Ossietzky, Kurt Tucholsky. Writer's trials in the Weimar Republic. Writings of the Erich Mühsam Society. Issue 14, Lübeck 1997, ISBN 3-931079-17-1 , pp. 54-69.

- Alfred Kantorowicz : The outlaws of the republic. in: portraits. German fates. Chronos, Berlin, 1947, pp. 5-24.

Individual evidence

- ^ Josef Walter Frind: The treason in German criminal law. Breslau 1931, p. 69.

- ↑ From an Old Soldier: The New Ranking List. In: The world stage. July 20, 1926, p. 83.

- ↑ Walter Bußmann et al. (Ed.): Files on German foreign policy. 1918-1945. Series B: 1925-1933. Volume XIX. October 16, 1931 to February 29, 1932. Göttingen 1983, p. 365.

- ↑ Heinz Jäger: Windy things from German aviation. In: The world stage. March 12, 1929, pp. 402-407, here: p. 407.

- ↑ Ursula Madrasch-Groschopp: The world stage. Portrait of a magazine. Berlin 1983, p. 257.

- ^ Gerd Kaiser: Windy things from German aviation (II). In: The leaflet . December 21, 1997.

- ↑ See: Ingo Müller : "The famous Ossietzky case from 1930 could repeat itself at any time ..." In: Hans-Ernst Bötcher (Ed.): Right Justice Criticism, Festschrift for Richard Schmid. Nomos, Baden-Baden 1985, pp. 297–326, here p. 307.

- ↑ According to the Republic Protection Act, this would have been a criminal offense. Compare: Ingo Müller, p. 305.

- ↑ The world stage process. In: The world stage. December 1, 1931, p. 803.

- ↑ Accountability. In: The world stage. May 10, 1932, p. 691.

- ↑ New York Evening Post, November 24, 1931.

- ↑ Accountability. In: The world stage. May 10, 1932, p. 690.

- ↑ Gerhard Jungfer, Ingo Müller : 70 years of the Weltbühnen judgment. In: Neue Juristische Wochenschrift ( NJW ). 2001, p. 3464 f.

- ↑ Is there a new Ossietzky case looming? In: Der Spiegel . No. 45 , 1964 ( online ).

- ↑ a b see: Ingo Müller : The famous Ossietzky case from 1930 could be repeated at any time ... In: Hans-Ernst Bötcher (Ed.): Right Justice Criticism, Festschrift for Richard Schmid. Nomos, Baden-Baden 1985, pp. 297-326, here p. 320 f.

- ↑ BGH StB 6/92 - decision of December 3, 1992 (KG Berlin) published on the website hrr-strafrecht.de . Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ↑ Ivo Heiliger : Windy things from German jurisprudence. The Ossietzky decision of the Federal Court of Justice. (PDF; 496 kB).

- ↑ Gerhard Jungfer, Ingo Müller: 70 years of the Weltbühnen judgment. In: Neue Juristische Wochenschrift (NJW). 2001, p. 3465.