Marcel Reich-Ranicki

Marcel Reich-Ranicki [ maʁˈsɛl ˌʁaɪ̯ç ʁaˈnɪʦki ] (born on June 2, 1920 as Marceli Reich in Włocławek ; died on September 18, 2013 in Frankfurt am Main ) was a German - Polish author and publicist . He is considered the most influential German-speaking literary critic of his time.

Reich-Ranicki was a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto . In 1958 he moved to the Federal Republic of Germany, where he worked as a literary critic, first for the weekly newspaper Die Zeit , then for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . He was a major critic in Group 47 , spokesman for the jury of the Ingeborg Bachmann Prize and initiator of the literary program The Literary Quartet , which he moderated from 1988 to 2001. Reich-Ranicki, known in public as the "Pope of Literature", also became a media star through legendary television appearances. His memoir Mein Leben (1999, film version 2009) continued to increase his popularity.

Reich-Ranicki was married to Teofila Reich-Ranicki and father of their son Andrew Ranicki .

Life

Włocławek

Marceli Reich was the third child of the factory owner David Reich and his wife Helene, b. Auerbach, born. He grew up in an assimilated Jewish German-Polish middle class family . His older siblings were Alexander Herbert Reich (1911–1943) and Gerda Reich (1907–2006). The mother was German and felt lost in the Polish province of Kujawy . Her great longing was to return to Berlin . Reich-Ranicki describes her as very loving and at the same time "unworldly". The father owned a small factory for building materials. But he was unhappy and “completely unsuitable” in the commercial profession. In 1928 the father had to file for bankruptcy. Marceli Reich was the only one of his siblings to attend the German school in Włocławek (Leslau) .

Berlin

In order to keep his professional future open to him after his father's business ruin, his parents sent him to live with wealthy relatives in Berlin, including a patent attorney and a dentist. From 1929 Reich-Ranicki lived first in Berlin-Charlottenburg , then in the Bavarian Quarter in Berlin-Schöneberg . There he attended the Werner-Siemens-Realgymnasium , after its closure in 1935 the Fichte-Gymnasium in Berlin-Wilmersdorf .

While his schoolmates took part in school trips, sports festivals and National Socialist school assemblies, he was excluded. Instead, he immersed himself in reading the German classics and attended theaters, concerts and operas. The performances of Wilhelm Furtwängler and Gustaf Gründgens in particular gave him consolation and support in an increasingly restrictive environment. When it became known to him that Thomas Mann had publicly distanced himself from the Nazi regime, the latter became his role model not only in literary but also in moral terms. In spite of the many teachers who were oriented towards the National Socialists, the principle of equal treatment of Jewish students still applied for some time at the Fichte Gymnasium; in 1938 he was still able to do his Abitur . His application for enrollment at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin was rejected on April 23, 1938 because of his Jewish descent.

Warsaw, ghetto, underground

The end of October 1938 he was after a short detention in the " Poland action " along with about 17,000 Polish and stateless Jewish men, women and children after Poland reported . He took the train to Warsaw , where he didn't know anyone. He had to learn the Polish language again and remained unemployed for a year. On September 1, 1939, the German attack on Poland began the Second World War , which abruptly ended his job search. He met his future wife Teofila (Tosia) Langnas (March 12, 1920 - April 29, 2011) through a tragedy: Her parents were expelled from Łódź by the German occupying forces and dispossessed; Out of shame and desperation, her father Paweł Langnas hanged himself on January 21, 1940 in Warsaw. Reich-Ranicki's mother, who lived in the same house, found out about the accident and sent her son there to look after the daughter.

In November 1940 Reich-Ranicki was also forced to resettle in the Warsaw Ghetto . He worked for the council of elders (" Judenrat ") appointed by the occupation authorities as a translator and wrote concert reviews under the author pseudonym Wiktor Hart in the twice-weekly ghetto newspaper Gazeta Żydowska (German: "Jewish newspaper"). At the same time he worked in the ghetto underground archive of Emanuel Ringelblum . During this time of agony and ubiquitous death, he made survival measures a habit (later retained for life). Since then he has always sat facing the entrance in restaurants; a second shave in the afternoon reduced the risk of negative attention.

On July 22, 1942, SS-Sturmbannführer Hermann Höfle appeared in the main building of the “Judenrat” to order the “resettlement” of the ghetto, which was to begin on the same day. Reich-Ranicki was used to write the announcement. From the deportation - the transfer of the ghetto residents to the Treblinka extermination camp , as it turned out - were initially excluded a. Employees of the "Judenrat" and their wives. In order to protect his partner Teofila Langnas, Reich-Ranicki arranged for her to be married on the same day by a theologian employed in the same house.

The couple escaped deportation in January 1943 by fleeing on their way to the meeting place. From then on it lived hidden. During this time, Reich-Ranicki and his wife supported the Jewish Fighting Organization (Polish: Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa , short: ŻOB ) in obtaining a large sum of money from the treasury of the “Judenrat”. In recognition of this, they got a small part of the money; This was supposed to enable them to escape from the ghetto by bribing the border guards, which they succeeded on February 3, 1943. After brief interim hiding, they found refuge for sixteen months with the family of the unemployed typesetter Bolek Gawin and his wife Genia, where they stayed until September 1944 after the German suppression of the Warsaw Uprising and the occupation of the right bank of the Vistula by the Red Army . Through his dramatic retelling of important novels of German and European literature, Reich-Ranicki was able to reassure himself again and again of the inconsistent, always endangered pity of his helpers. The better he told the story, the higher his chances of survival. Telling for his life was also referred to by himself as the Scheherazade motif. They helped the two children of the Gawin family with their schoolwork and their parents with the illegal manufacture of cigarettes. After the liberation of Poland from Nazi rule, Gawin asked the two survivors not to mention that with his help they had survived the occupation of Poland by the Nazi troops because their lifesaver was afraid of his because of the anti-Semitism widespread in Poland Saving Jews to get into talk. After the war, the Reich Ranickis also thanked the Gawins with financial compensation. Until recently, the couple transferred some money to Gawin's daughter every now and then. The couple were also able to smuggle out a portfolio of drawings by Tosia Reich-Ranicki, which were only published in 1999. The motifs came from everyday life in the ghetto and showed, among other things, children emaciated to the bones and beating National Socialists. In 2006 the Yad Vashem memorial awarded the Gawin family, who hid the Reich-Ranicki couple with them from 1943 to 1944, the " Righteous Among the Nations " award at Gerhard Gnauck's request .

Fate of parents and siblings

Reich-Ranicki's parents, Helen and David Reich were in the gas chambers of Treblinka murdered. His brother Alexander Herbert Reich was shot on November 4, 1943 in the Poniatowa prisoner-of-war and labor camp near Lublin . His sister Gerda and her husband Gerhard Böhm managed to flee to London in 1939 , where she died in 2006 at the age of 99.

post war period

At the end of 1944 Reich-Ranicki began to work for the Polish communist secret police UB (Urząd Bezpieczeństwa) , shortly after the liberation of the city in early 1945 in Katowice , where he organized censorship , and then as head of operations, with the rank of captain, for the Polish foreign intelligence service (MBP) in the espionage directed against Great Britain . For a time he was even deputy head of the II., The operational department of the secret service, whose area of activity included Germany and the USA in addition to Great Britain. In 1948 he became Vice-Consul and took the name “Marceli Ranicki” because his family name “Reich” was too reminiscent of the Germans. He was sent as a resident to the Polish Embassy in London , where he was appointed as an agent leader and was personally responsible for the affairs of the Poles in exile. Under his direction, a file was kept with information on more than 2000 Polish emigrants. The democratically elected Polish government-in-exile had its seat in London at the time , although it received little international recognition.

Nonetheless, Reich-Ranicki was regarded by his colleagues as an “intelligentsia”, sometimes arrogant, and met with a corresponding number of reservations. After all, Reich-Ranicki had arbitrarily issued his brother-in-law a visa in London without asking his superiors for permission. His son Andrzej Alexander was born on December 30, 1948. At the end of 1949 he was recalled from London and returned to Warsaw. Despite his services in the secret police - among other things, he received two high civilian medals, the “Medal of Victory and Freedom” in 1946 and 1948 - his career ended abruptly. The secret service and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs dismissed him in early 1950. Because of "ideological alienation" he was excluded from the communist Polish United Workers' Party . He spent a few weeks in solitary confinement in prison, also as part of the Eastern Bloc-wide Stalinist campaign against “ rootless cosmopolitans ” and “ Zionist espionage ”, which was only carried out to a very limited extent under Jakub Berman in Poland.

Released from prison, he turned to literature and became a lecturer for German literature in a large Warsaw publishing house. He began working as a freelance writer at the end of 1951. However, in early 1953, the Polish authorities issued a publication ban that remained in force until the end of 1954. In 1955 he became an employee of the Polish state radio, where his wife also worked, and published in newspapers, including for the central organ of the Communist Party, Trybuna Ludu .

His applications for re-entry into the Polish secret service and rehabilitation within the Communist Party were granted in 1957, according to the file inspection of the journalist Gerhard Gnauck of the German daily Die Welt in the personnel files of the Ministry for Public Security (MBP). However, Reich-Ranicki claimed that he had never received the relevant letter.

The journalist Tilman Jens , a son of decades friend of Reich-Ranicki philologist Walter Jens had uncovered Empire Ranicki's intelligence activity and him on 29 May 1994 in WDR telecast culture Weltspiegel accused while working for the Polish communist secret dissident exile Poland to have "lured them back to their homeland" under false pretenses. Some of these emigrants were then sentenced to death by the Polish regime. In his replicas, which he finally carried out in his biography, Reich-Ranicki contradicted the "completely lies" allegations of aiding and abetting murder. His widespread silence about his secret service activities was due to an obligation to maintain secrecy, the breach of which he was threatened with "sharpest" consequences. Rather, he considered his “work for the secret service to be insignificant and superfluous”, but he accepted this because of the privileged and interesting living conditions. The historian Andrzej Paczkowski also contradicted Jens; there is no evidence that "Reich helped during his time in London to lure exiled Poles into a trap". However, through research by Gerhard Gnauck, it has become known that Reich-Ranicki was involved in detail with the repatriation of emigrants, according to a separate report filed in his personnel file. Since Reich-Ranicki downplayed his secret service activities in London as amateurish in his autobiography, published in 1999, concealed the specific official obligations of his London years researched by Gerhard Gnauck and eluded any further clarification, the allegations against him have not been dispelled.

Federal Republic of Germany

After neither a work nor a permanent residence permit could be obtained for him in Switzerland, Reich-Ranicki stayed in Frankfurt am Main on July 21, 1958 after a study trip to the Federal Republic of Germany . His wife had previously gone on vacation to London with their son Andrzej to make it easier for the entire family to leave the country from a bureaucratic point of view. From August 1958 Reich-Ranicki worked as a literary critic in the features section of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) . The feature editor of the FAZ , Hans Schwab-Felisch, suggested that he use the double name “Reich-Ranicki”, which he did without hesitation. Members of Gruppe 47 , Siegfried Lenz and Wolfgang Koeppen , helped him by letting him review their books, among other things. However, the head of the FAZ's literary department , Friedrich Sieburg , soon pushed Reich-Ranicki's exit from the editorial office. At the end of 1959, Reich-Ranicki and his wife moved to Hamburg-Niendorf . He brought his son Andrzej / Andrew, who had been left with his sister Gerda in London, to Hamburg, where he could attend an international school . From 1960 to 1973 Reich-Ranicki was a literary critic for the Hamburg weekly newspaper Die Zeit . Very early on he had enforced the right to select the books he wanted to discuss, but was never invited to participate in the editorial conferences.

In Hamburg he made the acquaintance of NDR editor Joachim Fest . When he became co-editor of the FAZ in 1973 , Reich-Ranicki was appointed head of the literary department of this newspaper. From 1986 the historians' dispute initiated by Fest increasingly strained their relationship. Until the official end of work in 1988, Reich-Ranicki had the freedom to print all authors, regardless of their political color, in the FAZ's feature pages. In particular, he developed a commitment to his favorite authors, whom he paid constant attention to. He earned literary merits by editing the Frankfurt anthology he founded , in which to date more than 1500 poems by German-speaking authors with interpretations have been gathered. In addition, for decades he has consistently pushed ahead with the project of selecting what, in his opinion, is the best works of German-language fiction . On June 18, 2001, Reich-Ranicki presented his magnum opus on this life theme in the weekly magazine Der Spiegel under the title Canon of German-Language Works Worth Reading. The anthologies are subdivided into "novels", "essays", "dramas", "stories" and "poems", but also contain the recommendation that some things should only be read in excerpts.

Reich-Ranicki advocated clearly understandable literary criticism. According to Frank Schirrmacher , his motto was: "Clarity, no foreign words, passionate judgment". It was his concern to inspire literature beyond the professional world.

Together with other literary friends, he initiated the Ingeborg Bachmann Prize in 1977 , which quickly became one of the most important German-language literary competitions and prizes.

Effect and awareness

From March 25, 1988 to December 14, 2001, Reich-Ranicki directed the program The Literary Quartet on ZDF , with which he achieved a high level of awareness among a larger audience. The show was characterized by a lively and controversial discussion culture. Even before this program he was known in professional circles as the “ Pope of Literature ” and was considered the most influential German-language literary critic of the present. His influence through the literary quartet is at the center of the key novel Death of a Critic by Martin Walser .

Reich-Ranicki also became popular beyond the literary scene. According to a survey in 2010, 98 percent of the German population knew his name.

As a result, Reich-Ranicki's life from the perspective of its contemporary history (persecution and survival as a Jew, relationship with the Polish regime) found great public interest in film and television . His autobiography was made into a film , and in 2012 he gave the main speech on Holocaust Remembrance Day in the German Bundestag as a contemporary witness .

Marcel Reich Ranicki Chair for German Literature in Tel Aviv

At the request of the “Friends of Tel Aviv University” in Germany in 2006, the Marcel Reich Ranicki Chair for German Literature was established at Tel Aviv University in 2007 : “… in a historical burden, a striking symbol of scientific relationships. Marcel Reich-Ranicki, who suffered so much from the brutality and human contempt of the Nazis, symbolizes the intellectual exchange between scientists ”. The Germanist and author Ruth Klüger was supposed to become the first visiting professor at the new chair in May 2009 with the subject of “Jewish women authors in German-language literature”, but declined because organizational questions were unanswered.

Marcel Reich-Ranicki position

On July 5, 2010, a “Marcel Reich-Ranicki job for literary criticism in Germany” was opened at the Philipps University of Marburg in his presence . The institution was initiated by Thomas Anz and archives all newspaper articles that the literary critic has collected and published. She owns the estate of his library as well as other works and materials that Reich-Ranicki donated to the university. The position forms part of the research focus on literature communication in the media .

Visiting professor and speaker

In 1968 and 1969 he taught at American universities , and from 1971 to 1975 he was visiting professor in Stockholm and Uppsala . In 1974 he received the position of honorary professor at the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen , in 1990 the Heinrich Heine visiting professorship at the Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf and in 1991 the Heinrich Hertz visiting professorship at the University of Karlsruhe .

On January 27, 2012, Reich-Ranicki described in the speech at the memorial hour for the day of remembrance of the victims of National Socialism in the German Bundestag, how he experienced the first day of the deportations to the Treblinka extermination camp as a translator of the "Judenrat" in the Warsaw ghetto . The seminar for general rhetoric of the University of Tübingen recognized the lecture with the award “Speech of the Year”.

Private life, family

Reich-Ranicki last lived in Frankfurt-Dornbusch . His wife Teofila died on April 29, 2011 at the age of 91. His son Andrzej (later Andrew Alexander Ranicki ) was a professor of mathematics ( topology ) at Edinburgh University . The British painter Frank Auerbach is Reich-Ranicki's cousin .

At the beginning of his autobiography, Reich-Ranicki writes that he has “no country of his own, no homeland and no fatherland”. In the end, his home was literature.

Reich-Ranicki was an atheist. In a 2006 television documentary, he stated, “God is a literary invention. There is no god. (…) I do not know anyone. I never knew him. Never in my life! "He described religion as" glasses that cloud the view of reality, that make bitter realities disappear behind a mild veil. "

death

On March 4, 2013, Reich-Ranicki announced that he had cancer. He died on September 18 of the same year at the age of 93 in a nursing home in Frankfurt am Main.

On September 26, 2013, a memorial service for family, friends and companions took place in Frankfurt's main cemetery . Numerous guests took part in it. Federal President Joachim Gauck laid a wreath , Hesse's Prime Minister Volker Bouffier gave a speech, and television entertainer Thomas Gottschalk also spoke at Reich-Ranicki's coffin. Also present were the chairman of the Frankfurt am Main Jewish community and vice- chairman of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, Salomon Korn, as well as Lord Mayor Peter Feldmann and the former Lord Mayor Petra Roth . The grave of Marcel Reich-Ranicki and his wife is in the Frankfurt main cemetery (Urnenhain, Gewann XIV 34 UG).

Literary criticism

Positions

Reich-Ranicki favored realistic literature such as that written by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , Theodor Fontane and Thomas Mann . In addition, he valued the canonical works of modernism, such as Döblin's Berlin Alexanderplatz or Kafka's Process , but they never achieved the appreciation, let alone admiration, that he showed Thomas Mann and his work. On the other hand, he did not hesitate to take sides with young writers; Reich-Ranicki, often seen as a bourgeois critic, admired the work Tauben im Gras by Wolfgang Koeppen, which was based on modern literature . He realized the importance of the tin drum by Günter Grass only late, but he gave a positive review of Thomas Bernhard's prose , whose works are characterized by the use of the inner monologue and stream of consciousness .

The avant-garde literature, he was often reserved against, stressing that this will survive quickly. His canon contains neither the poet Hugo Ball nor his caravan , a key poem of Dadaism . Even Hans Arp is with its more traditional poems, Kurt Schwitters Ursonata or An Anna Blume had to just give way to a parody ballad. In his volume of essays, Sieben Wegbereiter , he accepted the literary importance of the avant-garde artists Alfred Döblin and Robert Musil , but did not forget his distant attitude towards them. Apart from Berlin Alexanderplatz , Döblin's novels are completely illegible and Musil is a failed narrator whose main work The Man Without Qualities has been grossly overestimated. Arno Schmidt made a similar judgment . Newer currents such as the Nouveau Roman did not find favor either.

In German poetry, he particularly valued those poets who knew how to combine intelligence and poetry, thus rejecting the one-sided seer and priest role of Holderlin or Rilke just as much as the radical supporters of committed literature . He counted Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Heinrich Heine and Bertolt Brecht among those poets of the German language who had succeeded admirably with this synthesis. He also thought little of feminist literary studies or socialist realism .

Reich-Ranicki also moved outside of high literature. He reviewed the perfume by Patrick Süskind and admitted that he would be happy to propose a detective novel like Der Richter und seine Henker for the Ingeborg Bachmann Prize . The trivial literature , however, did not find his recognition, but he preferred the argument to the blanket devaluation: "I tried to show how these novels are made and that their success was by no means a coincidence." From genre literature such as science fiction and fantasy Reich-Ranicki thought little without ever having dealt extensively with her; He believed especially of science fiction that its virtues "had nothing to do with art".

Individual reviews of contemporary authors

Günter Grass

Reich-Ranicki criticized the tin drum at first as an above-average, but not significant, work. In 1963, he revised his review “Tumbled on good luck” under the title “Self-criticism of a critic”. The novella Katz und Maus and theshortstory Das Treffen in Telgte received his praise, while the novels Der Flounder , Die Rättin and especially Ein weites Feld were sharply criticized. He judged the poetry of the author far more positively than the other literary criticism.

Heinrich Boell

Reich-Ranicki sponsored Heinrich Böll in order to enforce him against Gerd Gaiser as the representative of German post-war literature . Conservative literary critics like Hans Egon Holthusen and Friedrich Sieburg saw Gaiser as the leading writer in the FRG in the former NSDAP member, whereas Reich-Ranicki and Walter Jens took a different view. Originally he regarded Wolfgang Koeppen as the most important novelist, but this published only sparingly. While Reich-Ranicki considered Böll's novels to be insignificant from a literary point of view, he judged the short stories The Man with the Knives , Reunion in the Alley , Wanderer, Are You Coming to Spa ... and the satirical story Doctor Murke's collected silence positively.

Martin Walser

Overall, he assessed Martin Walser's work extremely critically. While he accused the novels of a lack of narrative power, Reich-Ranicki rated the novella A Fleeing Horse as Walser's most important work. After Walser's key novel Death of a Critic , the critic diagnosed the "total breakdown of a writer".

Thomas Bernhard

Thomas Bernhard , Günter Grass and Wolfgang Koeppen were considered by the critic to be the most important prose talents after 1945. He defined Bernhard as an outsider within German literature, whose novels and stories would be particularly linguistically distinguished. He understood the dramatic work as a “semi-finished product” that only Claus Peymann was able to realize .

Max Frisch and Friedrich Dürrenmatt

According to Reich-Ranicki, Max Frisch's importance lay in prose. He saw the three novels Stiller , Homo faber and Mein Name sei Gantenbein as well as individual passages from the literary diary as the greatest literary achievement of the Swiss. He included Frisch's story Montauk in his 20-volume canon of novels. In contrast, he regarded Friedrich Dürrenmatt's novels as successful entertainment literature; With the exception of the story Die Panne , Dürrenmatt did not create any highly literary prose of importance. Ranicki represented a minor opinion within German literary criticism that Dürrenmatt only wanted to see understood as a playwright. Reich-Ranicki found the dramas The Visit of the Old Lady and The Physicists to be the author's most important works; he included the former in his canon alongside the narrative.

Elfriede Jelinek and Peter Handke

Reich-Ranicki judged the Austrian writer: “ Elfriede Jelinek's literary talent is, to put it carefully, rather modest. Your dramas cannot be performed. She never succeeded in writing a good novel, almost all of them are more or less banal or superficial. "

Even Peter Handke heard a negative assessment. Reich-Ranicki wanted Handke's importance to be reduced to his image alone. Nevertheless, he took Handke's tale The falling of the skittles from a rural bowling alley in his canon.

Wolfgang Koeppen, Hermann Burger and Ulla Hahn

Pigeons in the grass by Wolfgang Koeppen was one of Reich-Ranicki's greatest novels after 1945. He supported Koeppen with commissions and even collected donations. Similar to Ulla Hahn ,he sponsoredthe Swiss Hermann Burger , so that some critics accused him of being entirely the critic's creations. Reich-Ranicki considered Ulla Hahn to be the most important representative of the New Subjectivity , whereas he recognized Ingeborg Bachmann as the most important female poet after 1945.

Criticism of Reich-Ranicki

The emotional commitment in his reviews, the sometimes rigorous judgments and the educational impetus, which concerned not only the work but also the author, aroused the rejection of numerous writers. Rolf Dieter Brinkmann said to Reich-Ranicki in a panel discussion in 1968: "If this book were a machine gun, I would now shoot you over the heap". Peter Handke said in an interview with André Müller that he would not regret it if Reich-Ranicki died. Elfriede Jelinek described Reich-Ranicki's statement that she (Jelinek) was a great woman, but she hadn't succeeded in writing a good book, as “greatest humiliation” and “contempt”. Günter Grass said that Reich-Ranicki “brought about the trivialization of criticism” and was a “weak literary critic”. Martin Walser's novel Death of a Critic is considered a general settlement with Reich-Ranicki .

Some colleagues judged no less sharply. "The self-righteous, indiscriminately angry roar of hatred of the unleashed culture philistine," commented Andreas Kilb on a statement by Ranicki. He was attacked several times in the journal Konkret . A few weeks after his death, Michael Scharang protested against the public judgment that Ranicki was the country's greatest literary critic. Denis Scheck said: "He was not always the brightest, but always the most amusing critic of his generation."

honors and awards

In 2006 the Humboldt University of Berlin decided to award Reich-Ranicki an honorary doctorate . As the legal successor to the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, which Reich-Ranicki had refused to study due to his Jewish religious affiliation, the Humboldt-Universität wanted to admit its historical responsibility and guilt in the run-up to its bicentenary, explained the university president. The award ceremony took place on February 16, 2007.

For his life's work and his program The Literary Quartet , Reich-Ranicki was to be awarded the German TV Prize on October 11, 2008 . Spontaneously referring to the “nonsense we got to see here tonight,” he declined the award. Moderator Thomas Gottschalk then offered Reich-Ranicki a one-hour discussion on the quality of German television together with the directors of ARD , ZDF and RTL , which he accepted. This led to a conversation between Gottschalk and Reich-Ranicki - without the participation of other people; the directors previously addressed by Gottschalk waived their participation. The ZDF broadcast the half-hour program recorded in Wiesbaden on October 17th, 2008 in the late evening program.

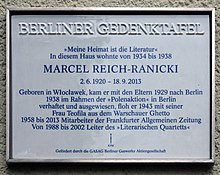

On September 12, 2014 , a Berlin memorial plaque was unveiled in front of his former home at Güntzelstrasse 53 in Berlin-Wilmersdorf .

Overview of all awards

- Silver and Gold Cross of Merit (Poland) (1946)

- Honorary doctorate from Uppsala University (1972)

- Honorary gift from the Heinrich Heine Society (1976)

- Ricarda Huch Prize (1981)

- Wilhelm Heinse Medal of the Academy of Sciences and Literature in Mainz (1983)

- Goethe badge of the city of Frankfurt am Main (1984)

- Great Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (1986)

- Thomas Mann Prize (1987)

- Bambi Culture Prize (1989)

- Hessian Order of Merit (1990)

- Bavarian TV Prize (1991)

- Hermann Sinsheimer Prize for Literature and Journalism (1991)

- Honorary doctorates from the University of Augsburg and Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg (1992)

- Wilhelm Leuschner Medal (1992)

- Ludwig Börne Prize (1995)

- Cicero Speaker Award (1996)

- Honorary doctorate from Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf (1997)

- Hessian Culture Prize (1999)

- Friedrich Hölderlin Prize of the City of Bad Homburg and Samuel Bogumil Linde Prize (2000)

- Golden Camera (2000)

- Honorary doctorate from the University of Utrecht (2001)

- Honorary doctorate from the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich (2002)

- Goethe Prize of the City of Frankfurt (2002)

- Grand Cross of Merit with Star of the Federal Republic of Germany (2003)

- European Culture Prize Pro Europa in the category European Media Prize / Award for Cultural Communication (2004)

- State Prize of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia (2005)

- Honorary doctorates from the Free University of Berlin and the University of Tel Aviv (TAU, 2006)

- Honorary doctorate from the Humboldt University of Berlin (2007)

- Patron of the chair for German literature at Tel Aviv University ( inauguration of the chair: 2007)

- Henri Nannen Prize for his journalistic life's work (2008)

- German Television Prize : Honorary Prize of the Donors in recognition of his work on the literary program Das Literäre Quartett (2008, declined )

- Officer in the Order of Orange-Nassau (2010)

- Ludwig Börne Medal (2010)

- International Mendelssohn Prize in Leipzig (Category: Social Commitment, 2011)

- Berlin Bear (2012)

- Speech of the year (given by the seminar for general rhetoric at the Eberhard Karls University in Tübingen) 2012 on the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of National Socialism , held on January 27 in the German Bundestag

Create

Fonts (selection)

- Literary life in Germany. Comments and pamphlets. Munich, Piper Verlag 1963.

- German literature in West and East. Piper, Munich 1963.

- Who writes provokes. Pamphlets and comments. dtv, Munich 1966.

- Literature of the small steps. German writers today. Piper, Munich 1967.

- The unloved. Seven emigrants. Günther Neske, Pfullingen 1968.

- In terms of Böll. Views and Insights. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1968.

-

Lots of tears . Piper Munich 1970.

- also: dtv, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-423-11578-5 .

- Lots of eulogies. DVA 1985 ISBN 978-3-421-06282-6 .

-

About troublemakers. Jews in German Literature. Piper, Munich 1973.

- extended 2nd edition: dtv, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-421-06491-1 .

- Review. Essays on German writers from yesterday. Piper, Munich 1977.

- Reply. On the German literature of the seventies. DVA, Munich 1981.

- Thomas Mann and his family. DVA, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-421-05864-4 .

- Heart, doctor and literature. Zurich 1987.

- The double bottom. A conversation with Peter von Matt. Ammann, Zurich 1992.

- The advocates of literature. DVA, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-423-12185-8 .

- Monster up. About Bertolt Brecht. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-932017-48-X .

-

The Heine case. DVA, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-421-05109-7 .

- also: dtv, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-423-12774-0 .

- also in Dutch translation.

- Seven pioneers. 20th century writer. DVA, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-421-05514-9 .

- Goethe again. Speeches and comments. DVA, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-421-05690-0 .

- My pictures. Portraits and essays. DVA, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-421-05619-6 .

- Lots of difficult patients. Conversations with Peter Voss about writers of the 20th century. List Verlag, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-548-60383-1 .

- Our grass. DVA, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-421-05796-6 .

- Demanded by the day. Speeches in German affairs. dtv, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-423-13145-4 .

- We're all on the same train. Insel Verlag , Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-458-19239-5 .

Autobiography

- My life. DVA, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-423-13056-3 . ( No. 1 on the Spiegel bestseller list from October 11, 1999 to October 15, 2000 )

As editor

- Germany tells stories there too. Prose from "Over there". Paul List Verlag, Munich 1960.

- 16 Polish storytellers. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1962.

- Made up truth. German stories since 1945. Piper, Munich 1965.

- Time seen. German stories 1918–1933. Piper, Munich 1969.

- Dawn of the present. German stories 1900–1918. Piper, Munich 1971.

- Defense of the future. German stories since 1960. Piper, Munich 1972.

- Frankfurt anthology . Insel Verlag, Frankfurt 1978–2010 [33 individual volumes].

- 1000 German poems and their interpretations. Insel, Frankfurt a. M. 1995. Ten volumes [anthology with interpretive texts].

- 1400 German poems and their interpretations. Chronologically from Walther von der Vogelweide to Durs Grünbein. Insel, Frankfurt 2002, ISBN 3-458-17130-4 . [Twelve volumes; Anthology with interpretive texts].

- My poems by Walther von der Vogelweide to this day. Insel, Frankfurt a. M. and Leipzig 2003, ISBN 978-3-458-17151-5 .

- Novels from yesterday - read today. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1996. [Three volumes; 1900-1918; 1918-1933; 1933-1945].

- My stories. From Johann Wolfgang von Goethe to today. Insel, Frankfurt a. M. 2003, ISBN 3-458-17166-5 [anthology].

- The canon . German literature. Novels. 20 volumes and an accompanying volume. Insel, Frankfurt 2002, slipcase , ISBN 3-458-06678-0 .

- The canon. German literature. Stories. 10 volumes and an accompanying volume. Insel, Frankfurt 2003, slipcase, ISBN 3-458-06760-4 .

- The canon. German literature. Dramas. 8 volumes and an accompanying volume. Insel, Frankfurt 2004, slipcase, ISBN 3-458-06780-9 .

- The canon. German literature. Poems. 7 volumes and an accompanying volume. Insel, Frankfurt 2005, slipcase, ISBN 3-458-06785-X .

- The canon. German literature. Essays. 5 volumes and an accompanying volume. Insel, Frankfurt 2006, slipcase, ISBN 3-458-06830-9 .

Audio books

- Left flush, right fluttering. Robert Gernhardt meets Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Recording from the International Literature Festival Lit.Cologne . Production: WDR , Random House Audio, Cologne 2008, 1 CD, ISBN 978-3-86604-976-5

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki reads Thomas Mann and his family. Try about love. Author reading. Production: Hessischer Rundfunk / hr2, Der Audio-Verlag, Berlin 2005, 2 CDs, 154 min., ISBN 3-89813-455-5

- Audio canon. German literature. Stories Edited and commented by Marcel Reich-Ranicki, Random House Audio, Cologne 2010, 40 CDs, 2800 min., ISBN 978-3-8371-0395-3

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki. My life. Original audio version of the TV film adaptation based on the autobiography of the same name Bellerive Hörverlag, Berlin 2012, 1 CD, 70 min., ISBN 978-3-941621-03-9

Television series

- The literary coffee house (1964–1967)

- The Literary Quartet (1988-2001)

- Reich-Ranicki Solo (2002)

- Lots of difficult patients (first started in 2001)

- What are our classics good for? (first time 2005)

estate

Marcel Reich-Ranicki's estate is in the German Literature Archive in Marbach . Parts of it can be seen in the permanent exhibition of the Modern Literature Museum in Marbach.

Filmography

- The literature pope. Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Germany / ZDF 2000, 60 min. A film by Reinhold Jaretzky and Roger Willemsen.

- The master of the books. Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Germany / ZDF 2005.60 min. Script and direction: Reinhold Jaretzky

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki at Beckmann . Talk, Germany, 2009, 29 min., Production: ARD , first broadcast: April 6, 2009

- Moving contemporary history. TV report, Germany, 2009, 5:09 min., Production: RBB , first broadcast: April 5, 2009

- An encounter with Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Documentation, Germany, 2009, 30 min., Written and directed: Mathias Haentjes, production: WDR , first broadcast: April 15, 2009

- My life - Marcel Reich-Ranicki . TV film , Germany, 2008/09, 90 min., Book: Michael Gutmann , director: Dror Zahavi , production: WDR , Katharina Trebitsch, first broadcast: arte , April 10, 2009; ARD , April 15, 2009, actors M. Reich-Ranicki: Matthias Schweighöfer , Teofila Reich-Ranicki: Katharina Schüttler , IMDb entry :, film page:

- I, Reich-Ranicki. Documentation, 105 min., Written and directed: Lutz Hachmeister and Gert Scobel , first broadcast: ZDF , October 13, 2006 (summary of ZDF), (review in Spiegel Online and Berliner Zeitung )

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki. My life. Documentation, 43 min., A film by Diana von Wrede, production: arte , first broadcast: August 21, 2004, synopsis by Phoenix

- Wonderful! Horrible! The great Marcel Reich Ranicki Night , documentary, 180 min., Compiled by Stephan Reichenberger and Alex Rühle, ZDF production , first broadcast: 2./3. June 2000

- The literature pope. Confrontations with the critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Documentation, 100 min., Script and direction: Martin Lüdke and Pavel Schnabel, first broadcast: ARD , April 28, 1987

literature

Biographies

- Thomas Anz : Marcel Reich-Ranicki . dtv, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-423-31072-3 (192 p., numerous mostly color illustrations).

- Frank Schirrmacher : Marcel Reich-Ranicki. His life in pictures. A picture biography. DVA, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-421-05320-0 (288 pages, 286 b / w illustrations, linen).

- Uwe Wittstock : Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Story of a life. Blessing , Munich 2005, ISBN 3-89667-274-6 (288 pp., 70 figs.), Review:

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki in the Munzinger archive ( beginning of article freely accessible)

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki: My life . Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag , Munich October 2000, ISBN 3-423-12830-5 .

Stages of life

- Sabine Gebhardt-Herzberg: The song is written with blood and not with lead: Mordechaj Anielewicz and the uprising in the Warsaw ghetto. Self-published, ISBN 3-00-013643-6 (250 pages; contains a chapter on Reich-Ranicki's escape from the Warsaw ghetto and the role of the so-called “Judenrat” for whom he worked).

- Gerhard Gnauck : Cloud and Willow. Marcel Reich-Ranicki's Polish Years. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-608-94177-7 (311 pages), excerpt , review

- Teofila Reich-Ranicki, Hanna Krall : It was the last moment. Life in the Warsaw Ghetto. Watercolors and texts. DVA, Stuttgart / Munich 2000, ISBN 3-421-05415-0 (120 pages, color, bound).

- e-Book: Ed. Hubert Spiegel : Marcel Reich-Ranicki and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. www.faz-archiv-shop, 2013.

- Carsten Heinze: Identity and History in Autobiographical Constructions of Life - Jewish and Non-Jewish Dealing with the Past in East and West Germany. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-531-15841-9 .

Meetings, celebratory speeches and awards, correspondence

- Thomas Anz (Hrsg.): The literature, a home - speeches about and by Marcel Reich-Ranicki. DVA, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-421-04380-1 .

- Hubert Spiegel (ed.): Encounters with Marcel Reich-Ranicki. it 3145, Insel-Vlg., Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-458-34845-X .

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki, Peter Rühmkorf : The correspondence. Edited by C. Hilse and S. Opitz. An edition by the Arno Schmidt Foundation in conjunction with the German Literature Archive Marbach. Wallstein, Göttingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-8353-1620-1 .

- Jürgen Klein: Dialogue with Koeppen . Wilhelm Fink, Leiden / Boston / Singapore / Paderborn 2017, ISBN 978-3-7705-6211-4 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Marcel Reich-Ranicki in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Marcel Reich-Ranicki in the German Digital Library

- Reich-Ranicki, Marcel. Hessian biography. (As of July 16, 2019). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- Reich-Ranicki, Marcel in the Frankfurt dictionary of persons

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki in the collection of articles in the Innsbruck newspaper archive

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Short biography and reviews of works by Marcel Reich-Ranicki at perlentaucher.de

- Annotated link collection ( Memento from December 27, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) from the library of the Free University of Berlin

- Who's Who: Reich-Ranicki's biography

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki and German literature. In: The National Library of Israel.

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki in conversation with Joachim Fest , in the series Witnesses of the Century , created in the project Memory of the Nation ( Interview , Part 1 - Duration 1:36:20 h).

Portals

- Internet portal Marcel Reich-Ranicki , literaturkritik.de with bibliography

- “The pop star of literary criticism. Marcel Reich-Ranicki on the 90th “ hr , audios, videos, photos and articles on his 90th birthday on June 2nd, 2010

items

- Gerhard Gnauck: "Neighbor, what do you need so much bread?" Die Welt, March 9, 2004 (about the endangered hiding place with the Gawin family)

- Christina Stefan: The godless pope of literature ( Memento from October 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), Humanistic Press Service, October 16, 2006

- Torsten Harmsen : Infinite melancholy and immense irony , Berliner Zeitung , February 17, 2007, on the award of an honorary doctorate from the Humboldt University of Berlin

- Frank Schirrmacher : A conversation with Marcel Reich-Ranicki. It was a lot easier than I imagined. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , June 3, 2008

- Michael Gotthelf : "In the meantime, they didn't want me!" , Neue Zürcher Zeitung , June 2, 2014 (on Reich-Ranicki's relationship with Switzerland)

Video

- 2008 Marcel Reich-Ranicki rejected the German Television Award from [3]

Individual evidence

- ↑ Philipp Peyman Engel: Dear luck. Jewish General , March 14, 2010.

- ↑ a b c Speech by Marcel Reich-Ranicki on the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of National Socialism on bundestag.de

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki: My life. P. 272 ff.

- ↑ a b Harald Jähner: To tell his life. In: Berliner Zeitung , June 2, 2005.

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki in Beckmann , April 6, 2009

- ↑ Gerhard Gnauck: “Neighbor, what do you need so much bread?” In: Die Welt , March 9, 2004

- ^ Teofila Reich-Ranicki died at the age of 91 In: ORF , April 29, 2011.

- ^ Gerhard Gnauck: How Reich-Ranicki organized censorship in Poland. In: Die Welt , March 10, 2009.

- ↑ The past (mirror)

- ^ Affaires: "They were harmless reports" Interview with the literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki about his past in the secret service (Spiegel)

- ↑ Gerhard Gnauck: "Knows the agent's psyche". In: Die Welt , August 12, 2002.

- ↑ NN : What are the medals for? In: Focus , No. 27, 1994.

- ^ Jacek syn Alfreda: Marcel Reich-Ranicki - "papież" w randze kapitana UB. In: salon24.pl , September 18, 2012.

- ↑ Gerhard Gnauck: "Knows the agent's psyche". In: Die Welt , August 12, 2002.

- ↑ a b G.Z .: possessed. Why does Tilman have to persecute Jens MRR so persistently? ( Memento from April 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) In: epd medien , No. 67, August 28, 2002.

- ↑ a b T.A .: Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Dispute over Reich-Ranicki's work for the Polish secret service. In: literaturkritik.de , April 17, 2004.

- ↑ The paperback edition from 2009 only says: “In addition, we (outside the consulate) had ten to fifteen employees, mostly unemployed or retired journalists. They regularly informed us about the Polish emigration ... For a modest fee they reported in detail on mostly inconsequential incidents of any kind ... I myself had no contact with Poles in exile ... It was my job to examine and follow up the various information and reports Forward to Warsaw. ”; Marcel Reich-Ranicki, Mein Leben , Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, 6th edition, 2009, p. 326 f.

- ↑ Michael Gotthelf: “However, they didn't want me!” In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung , June 2, 2014.

- ↑ Gerhard Gnauck: "I politely ask you to give me permission" In: Die Welt , July 21, 2008.

- ↑ Claudia Michels: "Everyone knew how they sounded" In: Frankfurter Rundschau , September 19, 2013.

- ↑ Volker Hage , Johannes Saltzwedel: Noah's Ark of Books , Der Spiegel , June 18, 2001, No. 25.

- ↑ Volker Hage : Literature must be fun , Der Spiegel , June 18, 2001, No. 25, interview

- ↑ Frank Schirrmacher : A very great man. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , September 18, 2013.

- ↑ Arno Widmann : The story of a triumph. Frankfurter Rundschau , June 1, 2010

- ↑ Peter von Matt : He writes for everyone - and knows how to do it. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , June 2, 2010.

- ↑ a b Volker Hage : A memorial for the critic. In: Spiegel Online , October 13, 2006.

- ↑ Thomas Maier: Reich-Ranicki Superstar , Main-Post , June 1, 2010

- ↑ Tel Aviv University: TAU Webflash, February 2006, Abroad ( Memento from October 9, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Hans Riebsamen: Support for the State of Israel. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine , March 6, 2007, online . Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ↑ uni-marburg.de: Opening of "job Marcel Reich-Ranicki for literary criticism in Germany" ( Memento of 2 May 2015, Internet Archive ) July 5, 2010

- ↑ literaturkritik.de : Marcel Reich-Ranicki's office for literary criticism in Germany , December 9, 2012

- ↑ Thorsten Schmitz: And now? MRR is reminiscent of the Warsaw ghetto - and touches the German parliament. But how will the memory of the Holocaust stay alive? In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , Jan. 28, 2012, p. 3.

- ↑ a b Speech of the Year. 2012 - Marcel Reich-Ranicki: Speech on the Day of Remembrance for the Victims of National Socialism

- ↑ Felicitas von Lovenberg : The rock in his surf. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , April 29, 2011.

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki: My life. P. 11f. "I was never half a Pole, never half a German - and I had no doubt that I would never become one."

- ↑ Excerpt from Ich, Reich Ranicki , about God: [1]

- ^ The last conversation with Reich-Ranicki, Focus Online: [2]

- ↑ "I fight against cancer". Süddeutsche Zeitung , March 4, 2013

- ↑ Literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki is dead. Süddeutsche Zeitung , September 18, 2013

- ↑ Frank Schirrmacher: A very great man . On: faz.net on September 18, 2013

- ^ Johan Schloemann: Funeral service for Marcel Reich-Ranicki: In literary society , Süddeutsche Zeitung , September 26, 2013

- ↑ Cf. Timm Boßmann: The poet in the field of fire. History and failure of literary criticism using the example of Günter Grass. Tectum, Marburg 1997, p. 114.

- ↑ See Der Kanon Die deutsche Literatur. Novels.

- ↑ Bianca Theisen: In the peep box of the head. Thomas Bernhard's autobiography. In: Franziska Schössler and Ingeborg Villinger (eds.): Politics and media with Thomas Bernhard. , Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2002. pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Cf. Marcel Reich Ranicki: Sieben Wegbereiter. Writer of the twentieth century. DVA, Stuttgart, Munich 2002. The chapter on Robert Musil reads: The collapse of a great narrator

- ↑ Cf. Marcel Reich Ranicki: Sieben Wegbereiter. Writer of the twentieth century. DVA, Stuttgart, Munich 2002, p. 168. The man without qualities had failed and Musil was actually a completely failed man.

- ↑ See Selfmadeworld in Halbtrauer Die Zeit , October 13, 1967

- ↑ See Geistreich, witzig, intelligent Focus , January 9, 2006

- ↑ Cf. Marcel Reich-Ranicki: First live, then play. About Polish literature. Wallstein, Göttingen 2002, p. 53.

- ↑ "I was never wrong" ( Memento from May 28, 2015 in the Internet Archive ), Stern , July 2, 2006

- ↑ See question Reich-Ranicki. A wonderful poetic critic of the times , FAZ , April 3, 2007

- ↑ See question Reich-Ranicki. Koeppens writing inhibition , FAZ , October 25, 2007

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki: Tumbled on good luck . In: The time of January 1, 1960.

- ↑ See self-criticism of the critics . In: The time of August 23, 1963.

- ↑ See question Reich-Ranicki. Will Heinrich Böll outlast his time? FAZ , May 28, 2008

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki judges the new novel by Martin Walser. Hamburger Abendblatt , May 31, 2003

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki in Lauter difficult patients (8/12), March 4, 2002

- ↑ See question Reich-Ranicki. Merciless moralist FAZ , November 14, 2006

- ↑ "Marcel Reich-Ranicki on Elfriede Jelinek". Spiegel , October 11, 2004

- ↑ Cf. “Ask Reich-Ranicki. His image is stronger than his work ”. FAZ , October 4, 2007

- ↑ Cf. Asta Scheib: Everyone is a work of art. Encounters. dtv, Munich 2006. p. 254.

- ↑ See A Shining Life. ( Memento from April 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Deutschlandfunk , September 21, 2013

- ↑ https://www.zeit.de/online/2008/46/rolf-dieter-brinkmann/seite-2

- ↑ https://www.profil.at/home/ich-idiot-sinne-182406

- ↑ https://www.profil.at/home/interview-ich-liebesmuellabfuhr-99059

- ↑ https://www.welt.de/print-welt/article398668/Marcel-Reich-Ranicki-ist-dafuer-mitverponslich.html

- ↑ https://www.zeit.de/1997/06/Der_Hausmeister , accessed on December 19, 2019.

- ↑ Press release from the Humboldt University in Berlin : Marcel Reich-Ranicki receives an honorary doctorate from the Humboldt University ( memento of December 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), December 20, 2006

- ^ Reich-Ranicki complains on German television , Die Welt , October 11, 2008

- ↑ Paweł Libera: Marcel Reich-Ranicki przed Centralna Komisją Kontroli Partyjnej (1950–1957) ( pl ) In: “Zeszyty Historyczne” 2009, no. 167 . ASSOCIATION INSTITUT LITTÉRAIRE KULTURA. Pp. 189-190. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ↑ Staats-Anzeiger, 6/2003, p. 526

- ↑ nrw.de: Prime Minister Jürgen Rüttgers awards the 2005 State Prize to the literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki , January 24, 2006

- ↑ Tel Aviv: University names chair after Reich-Ranicki , Spiegel Online , March 6, 2007

- ↑ Angelika Dehmel: Henri Nannen Prize 2008: Reich-Ranicki honored for his life's work , Stern , May 10, 2008

- ↑ Honorary award now finally rejected , Rheinische Post , October 12, 2008

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki rejects German television award (full length) on YouTube , accessed on June 21, 2020.

- ^ Mendelssohn Prize for Reich-Ranicki and Schreier. ( Memento from September 27, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) In: Sächsische Zeitung , July 7, 2011.

- ^ Literaturkritik.de : Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Literary criticism

- ^ Literaturkritik.de : Marcel Reich-Ranicki. solo

- ↑ Reich-Ranicki's estate goes to Marbach , Badische Zeitung

- ↑ IMDb: My Life - Marcel Reich-Ranicki

- ^ DasErste.de: Marcel Reich-Ranicki: Mein Leben ( Memento from April 14, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ news aktuell : Ich, Reich-Ranicki: Broadcast of the large ZDF documentary about the life of the star critic Reich-Ranicki: "I'm not at all disappointed with the film about my life" ( Memento from October 22, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) October 2006

- ↑ Hubert Spiegel : None other than him. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , October 12, 2006.

- ^ Arno Widmann : Lauter Laues , Berliner Zeitung , October 13, 2006

- ↑ Martin Lüdke : The monument fall does not take place. Frankfurter Rundschau , March 9, 2009

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Reich-Ranicki, Marcel |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Reich, Marceli (birth name); Hart, Wiktor (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Polish-German literary critic and publicist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 2, 1920 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Włocławek |

| DATE OF DEATH | 18th September 2013 |

| Place of death | Frankfurt am Main |