Robert Musil

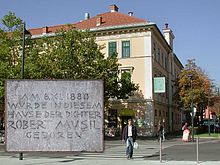

Robert Musil ( pronunciation: [ˈmuːzɪl] ; born November 6, 1880 in St. Ruprecht near Klagenfurt , † April 15, 1942 in Geneva ) was an Austrian writer and theater critic . The First World War and the establishment of National Socialist rule in Germany and Austria were significant cuts in his literary work .

Musil's work includes short stories , dramas , essays , reviews and two novels : The confusion of the Zöglings Törless appeared in 1906 , an example of modern literary work often used as school reading . From the 1920s until his death, Musil worked continuously on his major work The Man Without Qualities , which is part of the autobiographical aspect and which is part of world literature , without being able to complete it. The published interpretations of the works and research publications have not stopped since the 1950s.

Life and work pieces

As a writer, Musil was largely determined by his talents and the processing of his own experience. His literary estate primarily reflects his own career, his perception of the immediate social environment, the examination of current events and the interpretation of the intellectual currents of his time.

Family constellations and training

Robert Musil was the only son of the engineer and university professor Alfred Musil and his wife Hermine. The father came from Temesvár and grew up in Graz , where he also trained as a mechanical engineer. From 1873 Alfred Musil worked in Klagenfurt for the Hüttenberger Eisenwerk-Gesellschaft AG . Musil's mother Hermine was the daughter of the railway pioneer Franz Xaver Bergauer . Four years before Robert Musil was born, his older sister had died in 1876, to whom he, without having known her, felt a peculiar attraction. As can be seen from later diary entries, Musil sometimes had the desire to be a girl.

In 1881, one year after Robert Musil's birth, the family moved to Komotau in Bohemia, where the father worked as the director of the mechanical training workshop . After Alfred Musils changed jobs again, the family lived in Steyr in Upper Austria from 1882 , where Robert attended elementary school and the first class of the secondary school. In the parental home, Heinrich Reiter, a friend of his house, who was also regularly on the road and who was in a not entirely clear relationship to Robert's mother, frequented the family. Pfohlmann sees this constellation, which irritates the boy, as one of the causes of Musil's unstable gender identity.

In 1891 the father became a lecturer at the German Technical University in Brno . The family moved to Brno , where Robert went to secondary school. In the first half of 1891, Musil missed classes because of a "nervous and brain disease" (probably meningitis). From 1892 to 1894 Musil attended the military lower secondary school in Eisenstadt and from 1894 to 1897 the military upper secondary school in Mährisch Weißkirchen with the aim of becoming an officer. It was in this cadet institute that the experiences and experiences that Musil later processed in Törless came about . His last training center was the Austro-Hungarian Technical Military Academy in Vienna ; there he began training as an artillery officer. But after three months he broke off his career as an officer with his father's support and began studying mechanical engineering at the German Technical University in Brno in 1898 , where his father was rector. In addition to an extensive scientific workload, he found time to get involved in a number of clubs and associations in the training, which was accompanied by frequent exams. Fencing, tennis and water sports were among his favorite leisure activities. He was also one of the few early cyclists in Brno. The German Academic Reading Association, which Musil also joined, had 20 members, according to Corino, almost twice the strength of the cycling club. In addition to Friedrich Nietzsche , Ralph Waldo Emerson and Maurice Maeterlinck also had a greater influence on Musil's spiritual orientation at this time . On July 18, 1901, Robert Musil passed the second engineering examination with the overall grade "very capable".

From the turn of the century to the end of the World War in 1918

According to his own records, Musil's sex life at the turn of the century was mainly determined by experiences in the relationship with a prostitute, which he treated in part as experimental self-awareness. However, he was also deeply in love with the pianist and passionate mountaineer Valerie Hilpert, who took on mystical traits. From March 1902, suffering from syphilis, Musil underwent treatment with mercury ointment for a year and a half. During this time he began his relationship with Hermine Dietz, who worked in a cloth shop, for several years, the Tonka of his novel of the same name published in 1923. Hermione's syphilitic miscarriage in 1906 and her demise in 1907 could have been caused by infection from Musil.

After completing the one-year voluntary military service, Musil reoriented himself in his intellectual and professional interests after starting an internship as a research assistant at the Technical University of Stuttgart with the steam boiler researcher Carl von Bach on the recommendation of his father : Psychology and philosophy began, to keep him busy. In order to be able to study them as a subject, Musil still had to take his Abitur in 1902 and learn the ancient languages Greek and Latin. To study, he went to Berlin, where research, literature and theater opened up attractive perspectives for him and where Carl Stumpf had created a new research center for experimental psychology . “No other author of his generation,” says Pfohlmann about Musil, “except perhaps Hermann Broch , had such a broad knowledge”; no other work insists so emphatically on the unity of the humanities and natural sciences. Reading Ernst Mach , for whom physics and psychology belonged together and who, as a pioneer of Gestalt psychology, was important for Musil alongside Stumpf , acted as an important link .

Among his fellow students were the co-founders of the Gestalt theory Kurt Koffka and Wolfgang Köhler . Musil was particularly interested in the phenomenon of inversion in tilted images such as the Necker cube . In his first novel, The Confusion of the Zöglings Törless , published in 1906, the inversion motif already comes to bear on various occasions. After Musil had already received rejections for his manuscript from various publishers, he turned to the critic Alfred Kerr , who then even helped him with the final editing and who after the delivery of the novel with his review of the Törless, got it off to a dream start Debut contributed. In doing so, Musil also won over Franz Blei , who, as a literary mediator of modernism, now opened many publishing doors for him.

Parallel to the work on the Törless , Musil developed the Musil color spinning top named after him . He received his doctorate in 1908 from Carl Stumpf with a dissertation on Contribution to the Assessment of Mach's Teachings . The thesis received the grade laudabile confirmed by Alois Riehl in the rigorosum . Musil turned down an assistant position as an experimental psychologist in Graz with a subsequent habilitation in favor of the existence of a writer. With the story The Enchanted House (1908) and the volume of novellas, Associations (1911), Musil was unable to build on Törless’s success, and in retrospect he was unable to see a proper relationship between the cost and return of his efforts. In 1910 he moved to Vienna and took a position as a librarian at the Technical University of Vienna , which, however, restricted him in the long term and which he gave up after sick leave and stays at a spa. On April 15, 1911, Musil married Martha Marcovaldi, née Heimann (1874–1949). Until the beginning of the war in August 1914, he worked for several newspapers. The Neue Rundschau of the publisher Samuel Fischer , which brought out his sharp criticism of Walther Rathenau's Mechanik des Geistes , occupied him in its editorial office since February 1914. He was entrusted with the promotion of young writers and made numerous contacts with representatives of the expressionist literary scene. He had u. a. to do with Franz Kafka , who offered his story Die Verwaltung zum Druck, but withdrew it because the publisher had requested a shortening. In September of this year, the Neue Rundschau printed among other Musil's war-enthusiastic contribution Europeanism, War, Germanism , which denied the aesthetic values it had represented up until then.

In the First World War he took part as a reserve officer and finished him in the rank of landsturm captain with several awards. He was stationed on the Dolomite front , then on the Isonzo front. On September 22, 1915, near Trento, he was just missed by an arrow dropped by an Italian plane. He described this existential experience in the main scene of his story Die Amsel . In April 1916, after a serious illness, Musil was released from the field and took over the editing of the Tiroler soldiers newspaper in Bolzano . By the highest resolution of Emperor Charles I , Musil's father was raised to the hereditary Austrian nobility on October 22, 1917, as kk Hofrat and o. Professor of theoretical mechanical engineering and engineering at the German Franz-Joseph Technical University in Brno , whereby Musil himself also had the right to use this title. The award of the designation Edler von Musil and a coat of arms took place by diploma Vienna on February 5, 1918. In 1918 Musil was responsible for the homeland , also a military propaganda leaflet from the Vienna kuk war press quarters . Even after the end of the war, Musil was initially employed at this place of activity to secure his livelihood - now for the purpose of liquidation. Corino emphasizes that his knowledge of the files from the War Ministry was very useful to him for the later portrayal of Kakania in The Man Without Qualities , namely with regard to insights into the background of the war and the social and economic "interweaving and entanglement of all relationships in this realm. "

At the cutting edge in Berlin and Vienna until 1938

When Musil tried to determine his future perspectives from retrospect in 1919, he wrote down rather sobering notes in his diaries about his own previous work, which only partially appealed to him:

“But what remains of it? When the breath with which abundance was attempted is blown, an inorganic dead heap of material. The five years of war slavery has now torn the best part of my life; the run-up has become too long, the opportunity to exert all energy too short. Give up or jump, however it comes, is the only choice that remains. "

What was also to remain of Musil resulted essentially from his existence and his work as a writer in the period between the world wars, which he mainly spent in Berlin and Vienna.

In the vortex of post-war chaos (1919–1923)

The bourgeois prosperity of the first four decades of life was over for Musil in the years after the First World War. The fortunes of his parents and that of his wife Martha were consumed by the war and post-war inflation, and the income that remained during the remaining term of his employment in the War Ministry until December 1922 could not meet the previous requirements. Multiple changes of residence in Vienna at this time and intermittent stays in the facility held by Eugenie Schwarzwald for artists and intellectuals in need mark a social decline that Musil experienced as degrading. At the end of 1918 he supported the program of the “Political Council of Spiritual Workers” in Germany designed in the course of the November Revolution, alongside Heinrich Mann , Bruno Taut and Kurt Wolff , for example, in which, for example, the socialization of land, the confiscation of property beyond one Upper limit and the conversion of capitalist enterprises into workers' production cooperatives was called for. In March 1919, Musil pleaded in the Neue Rundschau for the post-war call for annexation to Germany, which was widespread among his compatriots, on the grounds that an independent Austrian culture was just legend.

Musil earned additional income primarily as a theater critic in the newspaper industry. In 1920 he completed his play Die Schwärmer , conceived a decade earlier, but only found a publisher for it the following year. The work, described by critics as a “ reading drama ”, was premiered in Berlin in 1929, heavily abridged and against Musil's resistance. It was almost the other way around with the farce Vincenz, which Musil posed as a counterpoint, and the friend of important men . It went quickly from his hand and was successfully performed at the end of 1923 even before the print version.

In the struggle for the Magnum Opus (1924–1932)

During this time after the Great Inflation , Musil's work gained more public attention overall. In February 1924, the volume of short stories Drei Frauen was published , in which three previous individual publications on the autobiographically primed female characters Grigia , Die Portugiesin and Tonka were summarized. Pfohlmann calls this volume of short stories comparatively “surprisingly accessible”. Even here Musil's prose is “interspersed with a dense network of similes and images that refer to each other, but the overwhelming wealth of images does not come at the expense of the plot. Rather, image and narrative levels combine in the Three Women to form a perfect union never again achieved in Musil's work. "

Two prizes honored Musil almost parallel to these new publications: the Kleist Prize awarded to him by Alfred Döblin and shared with Wilhelm Lehmann in October 1923 and the Vienna Art Prize awarded to him together with others in May 1924 . In November 1923, Musil was elected deputy chairman of the Association of German Writers in Austria. His commitment to the Ernst Rowohlts publishing house , with whom he contractually agreed a monthly advance payment for the elaboration of his major novel, provided better material security for his existence as a writer for the time being. However, over and over again, Musil fell behind considerably in meeting his deadlines. The novel - for the time being under the title The Twin Sister - was due to appear as early as autumn 1925 . Deaths in the family, the effect of Thomas Mann 's Zauberberg , published in November 1924, on Musil's own conception, health impairments in connection with a biliary operation in 1926 and frequent writer's block that could ultimately only be resolved with psychotherapeutic help are likely to have been important reasons for this.

The relationship with the publisher developed dramatically, not only from Musil's point of view, as Ernst Rowohlt testified in retrospect: Musil always made a great impression on him at encounters and was able to persuade him to provide further support, although he never got along with the agreed advance payments. Since Musil had also credibly threatened to shoot himself, he, Rowohlt, kept becoming soft. When the shock waves of the global economic crisis reached the German publishing industry and Musil still had not delivered on a large scale, Rowohlt's payments were temporarily canceled. He even had to wait longer for the prize money for the 1929 Gerhart Hauptmann Prize awarded to Musil . But Musil's explorations for a new change of publisher also failed. He remained dependent on Rowohlt.

Musil first presented the title The Man Without Qualities to the public in 1927 at a reading of parts of his work. At the beginning of 1929 he started the fair copy of the first volume, but it would take another two years for it to appear. According to his own admission, the author struggled to make progress:

“I also have a satisfying last and main part of the first chapter in my head. I continue the first part in a way that is formally awkward and that I delete. It occurs to me to insert the unused description of the noises and speeds of the big city here. I have in mind how it should move on to the last part. But imprecise and not fixed. Now the classic situation has been created: two fixed pillars and a transition between them that does not want to come about. I push it in and only partially accommodate it. I paint and try differently. Displeasure creeps in. I'm losing the line of it all. [...] It is evening, I leave the matter behind, read. At the moment when I want to turn off the lamps, it occurs to me, how often, how to do it. "

On December 22, 1930, a good two weeks after Musil's 50th birthday and too late to play a noticeable role in the Christmas business , Volume I of The Man without Qualities appeared . While Musil worked on the sequel in the two years that followed, she hit existential crisis of the Rowohlt publishing house with loss of income back on him. Again, Musil was unable to keep to his own schedule, but because of the precarious situation of his publisher, he also felt compelled to complete at least the first part of Volume II by the date announced by the publisher. His private plight was alleviated by a Musil society founded by private patrons, including Curt Glaser . Musil's admission to the Prussian Academy of the Arts failed despite the support of Thomas Mann and Alfred Döblins, for example, at the end of January 1932 due to the vote of the majority of members. The reason is said to have been: "too intelligent for a poet". Under such conditions, Volume II of The Man without Qualities was delivered with the first part on December 15, 1932 . Contrary to what it might seem, the title meant something completely different than a commentary on current political events: Into the Thousand Years' Reich (The Criminals) .

Vienna years before the "Anschluss" (1933–1938)

Musil and his Jewish wife Martha experienced the beginnings of the National Socialist regime in the Berlin Pension Stern on Kurfürstendamm . Alfred Kerr, Musil's sponsor for a good two and a half decades, whom Joseph Goebbels had long since declared one of the main political enemies, fled Berlin on February 15 due to the impending persecution. The next day the Rowohlt publishing house was raided by an SA formation to clean up unpopular literature. Since the Berlin Musil Society was also in the process of dissolution, the couple left Berlin in May 1933 for Karlsbad, where Musil spent a spa stay due to biliary liver insufficiency and then returned to Vienna. The invitation from Klaus Mann to participate with his own contributions to the fascism-critical exile magazine Die Sammlung was initially treated with hesitation, then clearly refused, probably in order not to exclude the distribution of his own works, which were not yet expressly prohibited, in National Socialist Germany.

After the assassination of Engelbert Dollfuss in July 1934 by the National Socialists, the corporate state in Austria , supported since 1933 by the Fatherland Front , was continued under Kurt Schuschnigg . Musil, who largely avoided active political involvement, complained in December 1934 in the celebratory speech on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Association of German Writers in Austria, on the one hand, state funding for literature "according to the laws of the smallest human comprehension" and, on the other, the miserable situation in which the A dozen real poets ”. Personal experience background for this was probably the shame and effort that it cost the Musil couple since their return to win supporters for a new Musil society in Vienna, which should secure a livelihood for both of them. In the said speech under the title “The poet in this time”, Musil also referred to the collective-individual dual nature of humans and their respective historically specific characteristics. Collectivism has recently come to the fore:

“And it cannot be concealed that in our classical era he relied on“ humanity ”and“ personality ”, whereas today he appears anti-individualistic and anti-atomistic and is not exactly a passionate admirer of humanity. [...] For political reasons, the concepts of humanity, internationality, freedom, objectivity and others have become unpopular in many places. They are considered bourgeois, liberal, dismissed. They are suppressed, eliminated from their education, starved. Not all at once; some there, others there. For the poet, however, it is the concepts of his tradition with the help of which he has laboriously consolidated his personal self. He does not need to agree with all of them, he can strive to change them, so he remains attached to all of them, far more than one is attached to the soil on which one walks. The poet is not only the expression of a momentary state of mind, may it itself usher in a new era. Its tradition is not decades, but thousands of years old. "

The contemporary person, according to Musil in another passage of this speech, turns out to be dependent and "only becomes something solid" in association. This is shown by the National Socialist coup in Germany, which divided the country into stormy victors on the one hand and helpless, shy cowards on the other, without the individual being permanently determined in one way or another. According to Corino, Musil's appearance was probably the main reason why Musil was invited to give a lecture at the international writers' congress in defense of culture in Paris in June 1935. However , Musil's speech did not meet the expectations of the organizers and those invited from 28 countries, the majority of whom paid homage to the new Soviet cultural model and the popular front . He again underlined the trend towards collectivism of the time, but rejected any use of the cultural sphere by politics, be it on the part of the state, the class, the nation, the race or Christianity.

“Today, politics does not get its goals from culture, but brings them along and distributes them. It teaches us how we should only poetry, paint and philosophize. "

In contrast, Musil emphasized that culture is supranational as well as timeless, but not mere tradition that can simply be passed on from hand to hand; rather, what has come from another time and from elsewhere is reborn in creative people. Some well-worn and often misused terms are essential psychological prerequisites:

“For example freedom, openness, courage, incorruptibility, responsibility and criticism, these even more against what seduces us than against what repels us. The love of truth must also be part of it, and I mention it especially because what we call culture is probably not directly subject to the criterion of truth, but no great culture can be based on a skewed relationship to truth. Without such characteristics being supported by a political regime in all people, they do not come to light in the special talents either. "

Musil could not expect predominantly positive reactions from this plea, neither in Paris nor at home in Vienna, because politically he had not affiliated anywhere in the charged time. Now he, who was being held captive by the drafts of the continuation of his novel, was increasingly threatened with being forgotten by the literary public. Musil, who was at risk of high blood pressure, tried to maintain a certain athletic fitness by regularly swimming in the Viennese Dianabad . In May 1936 he suffered a stroke that resulted in various restrictions in future life. Musil's last major public appearance was a speech about stupidity in March and December 1937, which did not omit the reference to politics and fascism and thus casually underlined the introductory statement: “Someone who ventures to speak about stupidity is running today Danger of being harmed in many ways ... "

Exile in Switzerland until the end of his life

While Musil was still working on the proofs for the imminent publication of 20 more chapters for the second part of Volume II of The Man Without Qualities , the annexation of Austria to the National Socialist German Reich in March 1938 made the situation for the Musil couple in Vienna untenable: Gottfried Bermann Fischer , who had taken over the rights to Musil's complete works from Rowohlt in the previous year, was able to move abroad in good time; But there was now nothing left to order for Musil in Austria either, after his estate had already been banned by the Reichsführer SS during his lifetime . The search for a suitable country of exile turned out to be difficult. At home without any prospects, Robert and Martha Musil moved into exile in Switzerland in August 1938, first to Zurich via Vulpera , then to Chêne-Bougeries , near Geneva . They lived there in conditions that were perceived as desolate, against which Musil "fought with a flood of letters of appeal to friends, patrons, aid organizations and potential supporters all over the world." They found help from the Geneva pastor Robert Lejeune and the Swiss aid organization for German scholars .

On April 15, 1942, Robert Musil died of an ischemic stroke ("cerebral infarction") at Chemin des Clochettes 1 in Geneva. His widow Martha kept the death mask and the urn with the ashes in her Geneva apartment until July 1946 and scattered them at the foot of the Salève at the edge of two overgrown gardens before leaving for her daughter in Philadelphia .

An "inheritance during his lifetime"

While Musil was working on the continuation of his novel with increasing health problems and was hardly noticed by the public as a writer without new publications, he decided, on the advice of Otto Pächt, to publish a collection of earlier small writings and features, including the much-vaunted miniature at the beginning “The fly paper” and at the end the story “The Blackbird”. These works were published in December 1935 under the title Nachlass zu Leben , which Musil generalized in the "Preliminary remark":

“But can one still speak of a lifetime at all? Hasn't the poet of the German nation outlived himself long ago? It looks like this, and strictly speaking, as far back as I can remember, it has always looked that way, and has only recently entered a crucial phase. The age that produced the custom-made shoe from finished parts and the finished suit in individual adaptation also seems to want to produce the poet composed of finished inner and outer parts. Already the poet lives in his own measure almost everywhere in a deep seclusion from life, and yet he has nothing in common with the dead in the fact that they do not need a house and no food and drink. "

Coming up with small, apparently unimportant works in connection with the estate, Musil appeared risky on the one hand, but also justified on the other. Because "there has always been a certain difference in size between the weight of poetic utterances and the weight of the two thousand and seven hundred million cubic meters of earth racing through space untouched by them and somehow had to be accepted."

Musil again ironically reflects the relationship between the writer and the audience in one of the “Unfriendly Considerations” contained in the volume under the title “Among loud poets and thinkers”. Taking up the fact that books are “no longer big today” and that writers are supposedly no longer able to write such things, which should remain undisputed, Musil asks conversely how the reading ability of the public is going.

“Doesn't a hitherto unenlightened resistance, which is not the same as displeasure, grow in increasing potencies with the length of what has been read, especially if this is really a poem? It happens no differently as if the gate through which a book is supposed to enter was sickly irritated and closed tightly. Many people today, when they read a book, are not in a natural state, but rather feel subjected to an operation in which they have no confidence. "

People as consumers of culture are "insidiously dissatisfied with people as producers of culture." In day-to-day business, however, this goes wonderfully well with the opposite. In the news and reviews of the newspaper industry, a multitude of deep and great masters appear within a few months. It happens astonishingly often in such a short time that the nation is "finally given a true poet again", the most beautiful animal story and "the best novel of the last ten years" are written. "A few weeks later, hardly anyone can remember this unforgettable impression."

Elsewhere, under the title “Art Anniversary”, Musil deals with the discrepancy between the first impression a work of art leaves on the individual and the often quite different impression when they meet again years later: “The gloss is gone, the importance is gone, dust and Moths fly up. ”The negatively changed impression, from which only“ great art ”is excluded, comes about, according to Musil,“ that we become uncomfortable with ourselves as soon as we have a certain distance from ourselves. This stretch of horror at ourselves begins a few years before now and ends roughly with the grandparents, i.e. where we begin to be completely uninvolved. Only what begins there is no longer out of date, but old, it is our past and no longer what has passed from us. "

“Apparently there is an exaggeration, a super plus and exuberance in the essence of the earthly. Even to a slap in the face you need more than you can justify. This enthusiasm of the now burns up, and as soon as it becomes unnecessary, oblivion extinguishes it, which is a very creative and content-rich activity, through which we really emerge again and again as that uninhibited, pleasant and consistent person for the sake of which we find everything in the world justified. "

Effect and reception

Robert Musil is best known as the author of the two novels The Confusions of the Zöglings Törless and The Man Without Qualities . After the success of Törless in 1906, which established his existence as a writer, Musil found it difficult to achieve further public success. Almost a quarter of a century passed before the main work was published, during which time Musil stood out mainly with literary criticism, newspaper articles and theater works and did not receive any special attention in the literary business.

After the First World War, which was experienced as a biographical and ideological break, Musil's main literary endeavors increasingly focused on the development of the major work, which was taking on ever larger dimensions. Making a living from the regular advances made by the publisher Ernst Rowohlt on this novel project, Musil gave up his journalistic activity as a tiresome job. With occasional literary publications, which were also due to the shortage of funds, he brought the literary public back to memory now and then.

The man without qualities was highly praised by the critics after the publication of the first volume in 1930, but was less popular with the general public than the Törless at the time, which even prominent advocates like Thomas Mann were unable to change. For Musil, the work on the sequel was increasingly marked by financial and economic hardships, so that the expectations aroused in the interested readership were put off. The novel project grew more and more in depth: Musil accumulated a complex system of notes comprising around 6,000 pages in his estate in drafts, concepts, variants and proofreads - and the production of texts ready for publication progressed more and more slowly.

At the pressure of his publisher, Musil published the completed first part of the second volume in December 1932. The response in the literary world was more reserved than after the first volume was published. The publication of a further part, last planned for April 1938, did not take place. Musil was still busy correcting the so-called proof chapters when the Nazi regime prevented the forthcoming publication with the annexation of Austria. In the last years of his life, Musil did not publish anything, despite constant work on the man without qualities, and was forgotten in exile in Switzerland; for he also abstained from political statements, perhaps in an effort not to appear to the authorities as a man in exile, but as a temporary foreigner for the purposes of study.

Klaus Amann sees Musil's behavior as only apparently apolitical and marks what is genuinely political about it: “That as a person he consistently refused to accept the time-bound, arbitrary and instrumental claims of politics - for a work whose theme is the time drifting towards war whose core, however, is the defense of the individual, of the autonomous, thinking and feeling person. " Musil wrote to the editor at Bermann-Fischer Verlag Viktor Zuckerkandl in 1938 from exile in Switzerland:" Even now I can't help but think about it: Certainly Germany is in smoke and maybe soon on fire, and then the world with him; but what can I save and keep in the consciousness of others, if not the work of which I am master and servant. "

A revival of interest in Musil's work began in the 1950s after Martha Musil and Adolf Frisé had put the deceased's legacy into order. Adolf Frisé obtained a new edition of the novel fragment and thus contributed significantly to its rediscovery. In the literary supplement of the Times of Oct. 28, 1949, Musil was described as "the most important novelist writing in German in this half-century", who was also "the least known writer of the age". Today the novel is considered to be one of the greatest works of modern times and is the subject of intensive research as a "prestige literary object". In 1965, Volker Schlöndorff filmed Musil's first film under the title The Young Törless . The film intensely charged Musil's material with questions about German guilt in the time of National Socialism and became a first great success for New German Film . As a result, Musil's Die Confusions des Zöglings Törless was for a long time a reading that was often used in school lessons.

In the narrower framework of the German-language literature of his time, Musil is not infrequently placed in a row with Hermann Broch , Franz Kafka , Thomas Mann , Elias Canetti and others, whose writing energy was often nourished like Musil's from collapse experiences that were as personal as epochal. In contemporary Austrian literature, Gerhard Amanshauser , Rudolf Bayr , Thomas Bernhard , Alois Brandstetter , Andreas Okopenko , Michael Scharang , Franz Schuh and Julian Schutting , among others , testify to the continued impact of his work in various ways and take positions of Musil in aesthetic and political terms.

Karl Corino , Musil's meticulous and interpretive biographer, summarizes his work and personality in his judgment: “The central idea of his work, namely that of accuracy and soul , has in our time, as airy fables and the logic of research are increasingly alien to each other , not lost in validity. ”The true power and dignity of the major work The Man Without Qualities , it is said, referring to Ignazio Silone , can be found in the person of the author Robert Musil,“ the one, struggling with his utopia, like someone buried alive rests in this work. "

research

In 1970 Marie-Louise Roth founded the permanent office for Robert Musil research at Saarland University , today's “Office for Austrian Literature and Culture / Robert Musil Research” (AfÖLK abbreviation). In 1974 she founded the “International Robert Musil Society” (abbr. IRMG) in Vienna with the then Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky as patron. Roth was president of the IRMG from 1974 to 2001, from 2001 its honorary president. Today the company has its headquarters in Klagenfurt . The current president of the company is Norbert Christian Wolf, managing director Harald Gschwandtner.

Musil's work, especially The Man Without Qualities , has motivated numerous Germanists to do their doctorate on Musil, including Dieter Kühn (1965), Karl Corino (1969), Dieter Fuder (1979), Roger Willemsen (1984) and Richard David Precht (1996 ).

Exhibitions

- 2014: The Song of Death. Robert Musil and the First World War . South Tyrolean State Museum for Cultural and Regional History , Tyrol Castle , Bozen, South Tyrol.

Memorial sites

In Klagenfurt (Bahnhofstrasse 50) there is the Robert Musil Literature Museum. There is also a Robert Musil memorial room at Rasumofskygasse 20 in Vienna- Landstrasse (3rd district). Memorial plaques and memorial stones can be found in Klagenfurt, Berlin-Charlottenburg and Geneva.

Designations

In 1956 the Musilplatz in Vienna- Ottakring (16th district) was named after him. There are other names (streets, alleys, paths and squares). a. within Austria in Eisenstadt, Traiskirchen, Graz-Liebenau, Villach, Wels, Marchtrenk, Kapfenberg and Klagenfurt, and also in Hamburg.

Works

For a list of all works see Wikisource

- The confusions of the pupil Törless (Wiener Verlag, Vienna and Leipzig 1906), 68th edition, Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-499-10300-1 ; also as audio book, ISBN 978-3-89940-194-3 .

-

Contribution to the evaluation of the teachings of Mach. Berlin 1908, OCLC 31082331 (Inaugural dissertation Universität Berlin 1908, 124 pages).

- New edition with Die Kraftmaschinen des Kleingewerbes , 1904; The heating of the living spaces. 1904/05; Psychotechnics and its application in the armed forces. 1922, as a contribution to the assessment of Mach's teachings and studies on technology and psychotechnology , Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1980, ISBN 3-498-04271-8 .

- The enchanted house (= first version of The Temptation of the silent Veronica ) (in: Hyperion 1908)

- The indecent and sick in art. Essay (in: Pan 1911)

- Associations. Two stories. (Georg Müller Verlag, Munich 1911) Also available as an audio book in full text reading. onomato Verlag, Düsseldorf, ISBN 978-3-933691-95-8 .

- The enthusiasts. Play in three acts. (Sybillen Verlag, Dresden 1921)

- Three women. Novellas. (Rowohlt Verlag, Berlin 1924). Three-part novella cycle consisting of Grigia. (First edition: Müller & Co. Verlag, Potsdam 1923), Die Portugiesin. (First edition: Rowohlt Verlag, Berlin 1923) and Tonka. (First printing: Gebr. Stiepel Verlag, Reichenberg in Böhmen 1922)

- The man without qualities (a first book was published in1930by Rowohlt Verlag, Berlin, containing part 1. A kind of introduction and part 2. The same thing happens ; a second book - published by Rowohlt Verlag, Berlin in 1933 - remained unfinished, it was and will be (re) constructed in various editions from the estate; a third volume, consisting of the estate, was printed by Musil's widow in exile in Switzerland in 1943); also as audio book, ISBN 978-3-89940-416-6 .

- Estate during lifetime. (Humanitas Verlag, Zurich 1936, therein the story Die Amsel )

- About stupidity. Lecture at the invitation of the Austrian Werkbund, given in Vienna on March 11th and repeated on March 17th, 1937. (separate edition). Bermann-Fischer Verlag, Vienna 1937.

-

Robert Musil - Collected Works . Edited by Adolf Frisé. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg:

- Volume I: prose and plays, short prose, aphorisms, autobiographical matters. ISBN 3-498-09287-1 . (1978)

- Volume II: Essays and Speeches. Criticism. ISBN 3-498-09287-1 . (1978)

- Volume III: The Man Without Qualities. First and Second Book. Novel. ISBN 3-498-09285-5 . (1978)

- Volume IV: The Man Without Qualities. From the estate. ISBN 3-498-09285-5 . (1978)

- Volume V: Diaries. ISBN 3-498-09289-8 . (1976)

- Volume VI: Diaries. Notes, appendix, register. ISBN 3-498-09289-8 . (1976)

- Volume VII: Letters 1901-1942. ISBN 3-498-04269-6 . (1981)

- Volume VIII: Letters 1901–1942, commentary, register. ISBN 3-498-04269-6 . (1981)

- The literary estate. CD-ROM edition. Edited by Friedbert Aspetsberger, Karl Eibl and Adolf Frisé. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1992 ( MS DOS -based user interface.)

- Robert Musil: The man without qualities. Remix. Published by Katarina Agathos / Herbert Kapfer . Bavarian radio / radio play and media art in cooperation with the Robert Musil Institute of the University of Klagenfurt . Scientific advice: Walter Fanta. Belleville, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-89940-416-5 .

- Robert Musil: Klagenfurt edition. Annotated digital edition of all works, letters and legacies. With transcriptions and facsimiles of all manuscripts. Edited by Walter Fanta, Klaus Amann and Karl Corino. Klagenfurt: Robert Musil Institute of the University of Klagenfurt. DVD version 2009.

literature

- Klaus Amann : Robert Musil - literature and politics. Reinbek near Hamburg 2007. ISBN 978-3-499-55685-2 .

- Helmut Arntzen: Musil commentary on all writings published during his lifetime except for the novel "The Man Without Qualities" . Winkler, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-538-07032-6 .

- Helmut Arntzen: Musil commentary on the novel "The man without qualities" . Winkler, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-538-07036-9 .

- Helmut Arntzen: Satirical style. On Robert Musil's satire in “Man without Qualities” . Bouvier, Bonn 1960. (3rd edition. 1983, ISBN 3-416-01746-3 )

- Wilhelm Bausinger: Studies on a historical-critical edition of Robert Musil's novel "The man without qualities" . ( Dissertation at the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen 1962). 3 volumes. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1964 DNB 481198776 .

- Wilfried Berghahn: Robert Musil. Picture monograph. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1988, ISBN 3-499-50081-7 .

- Silvia Bonacchi: The shape of poetry: The influence of the Gestalt theory on the work of Robert Musils . Lang, Bern 1998, ISBN 3-906760-48-0 .

- Karen Brüning: The Reception of Gestalt Psychology in Robert Musil's Early Work. Frankfurt, Peter Lang 2015, ISBN 978-3-631-66839-9 .

- Johanna Bücker: The sea and the other state. Genesis and structure of a leitmotif in Robert Musil , Fink, Paderborn 2016, ISBN 978-3-8467-6093-2 .

- Karl Corino : Robert Musil. Life and work in pictures and texts. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1988, ISBN 3-498-00877-3 .

- Karl Corino: Musil, Robert. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 18, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-428-00199-0 , pp. 632-636 ( digitized version ).

- Karl Corino: Robert Musil. A biography . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-498-00891-9 .

- Karl Corino: Daredevil and Trachinist - Robert Musil fought against the Italians in South Tyrol in World War I - a photo find provides information about this time . In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung , Zurich, No. 45, February 24, 2014. p. 37.

- Sibylle Deutsch: The philosopher as a poet. Robert Musil's theory of storytelling . Contributions to Robert Musil research and recent Austrian literature. tape 5 . Röhrig, St. Ingbert 1993, ISBN 3-86110-020-7 .

- Claus Erhart: The aesthetic person in Robert Musil. From aestheticism to creative morality. (German series of the University of Innsbruck). 1991, ISBN 3-901064-02-8 .

- Eckhard Heftrich : Musil. An introduction . Artemis, Munich / Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-7608-1330-5 (= Artemis Introductions , Volume 30).

- Villő Huszai: Digitization and the utopia of the whole . Thoughts on the complete digital edition of Robert Musil's work. In: Michael Stolz, Lucas Marco Gisi and Jan Loop (eds.): Literature and literary studies on the way to the new media. germanistik.ch, Bern 2005

- Markus Joch: More than war fury and thrill. First World War. In: taz , November 25, 2015, p. 15

- Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins: Robert Musil. An introduction to the work . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1962.

- Herbert Kraft : Musil . Zsolnay, Vienna / Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-552-05280-1 .

- Heribert Kuhn: The Bibliomenon: topological analysis of the writing process of Robert Musil's “associations”. Lang, Frankfurt am Main / Berlin / Bern / New York / Paris / Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-631-45809-6 (= Munich Studies on Literary Culture in Germany , Volume 22, also a dissertation at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich 1992 ).

- Matthias Luserke-Jaqui : Robert Musil . (Metzler Collection, 298). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 1995, ISBN 3-476-10289-0 .

- Thomas Markwart: The theatrical modern. Peter Altenberg, Karl Kraus, Franz Blei and Robert Musil in Vienna . J. Kovac, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-8300-1680-8 .

- Monika Meister : Robert Musil's concept of theater: a contribution to the aesthetic theory of theater. Diss. Univ. Vienna, 1979.

- Inka Mülder-Bach : Robert Musil: The man without qualities: An attempt on the novel . Hanser, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-446-24354-5 .

- Götz Müller: Ideology criticism and metalanguage in Robert Musil's novel "The man without qualities" . (Musil studies, 2). Fink, Munich / Salzburg 1972.

- Birgit Nübel and Norbert Christian Wolf: Robert Musil Handbook . De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-018564-5 .

- Oliver Pfohlmann: Robert Musil. (Rowohlt's monographs). Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-499-50721-2 .

- Marie-Louise Roth: Robert Musil. Ethics and Aesthetics, the theoretical work of the poet. List, Munich 1972, ISBN 3-471-66526-9 u. a.

- Regina Schaunig: The poet in the service of the general . Robert Musil's propaganda writings during the First World War. Kitab-Verlag , Klagenfurt 2014, ISBN 978-3-902878-40-3 .

- Rolf Schneider : The problematic reality, life and work of Robert Musil, attempt at an interpretation . Verlag Volk und Welt , Berlin 1975, DNB 760127131 .

- Ingeborg Scholz: Robert Musil. Its location and its poetry. (Amber shelf, 9). Bernstein, Bonn 2011, ISBN 978-3-939431-65-7 .

- Roger Willemsen : Poetry's Right to Exist. For the reconstruction of a systematic literary theory in the work of Robert Musil (= Munich Germanistic Contributions , Volume 34). Fink, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-7705-2237-0 . (Dissertation Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 1984.)

Web links

- Literature by and about Robert Musil in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Robert Musil in the German Digital Library

- Works by Robert Musil in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Works by Robert Musil in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available to users from Germany )

- Robert Musil on the Internet Archive

- Entry on Robert Musil in the Austria forum

- International Robert Musil Society (IRMG)

- Short biography http://www.rowohlt.de/autor/2531 Short biography and title list at Rowohlt-Verlag

- Musil portal of the Robert Musil Institute of the Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt (work edition)

- Robert Musil Institute for Literary Research, Klagenfurt

- Robert Musil Literature Museum, Klagenfurt

- Annotated link collection ( memento from January 29, 2016 in the web archive archive.today ) of the University Library of the Free University of Berlin

- Robert Musil in the literature archive of the Austrian National Library :

Remarks

- ↑ 1917 to 1919 as a result of the father's award on October 22, 1917 with the hereditary title: Robert Edler von Musil ; Emphasis on the family name on the 1st syllable .

- ↑ Norbert Christian Wolf: Kakanien als social construction. Robert Musil's Social Analysis of the 20th Century . Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 2011, p. 20 f.

- ↑ Corino interprets this tendency in more recent terms as a case of moderate transsexuality . (Corino 2003, p. 31 f.) The “twin sister” Agathe, who are closely related to Ulrich in The Man without Qualities, and the unifying tendency towards the mystical “other state” for Corino are not least to be derived from this disposition by Musil. ("As if everything was decided in childhood")

- ↑ Pfohlmann 2012, p. 14.

- ↑ Corino 2003, p. 44 Musil describes a similar episode of illness in The Man without Qualities from the earlier life of Ulrich's “twin sister” Agathe.

- ↑ Corino 2003, pp. 127-135.

- ^ Corino 2003, p. 1878.

- ↑ Corino 2003, pp. 151-154.

- ↑ Pfohlmann 2012, pp. 32–34; Corino 2003, pp. 156-167. Pekar comments: "Sigmund Freud's observation of the division of love life into eros and sex, into the distant, pure beloved and the whore, find their clear confirmation here." (Pekar 1997, p. 13)

- ↑ Pfohlmann 2012, p. 34; Corino 2003, pp. 190-194 and pp. 1882 f.

- ^ Corino 2003, pp. 208 and 219.

- ↑ Pfohlmann 2012, p. 38 f.

- ↑ The influence of gestalt theoretical thought then permeates Musil's entire literary work. (Silvia Bonacchi: The Shape of Poetry: The Influence of the Gestalt Theory on the Work of Robert Musils . Lang, Bern 1998; Karen Brüning: The Reception of Gestalt Psychology in Robert Musil's Early Work . Frankfurt, Peter Lang 2015.) “The stimulus of the Gestalt theory contributed Musil lifelong on his work, both in detail and as a whole, in individual passages and in the conception of his chef d'œuvre, in which narrative and essayistic passages should come together to form a convincing figure. "(Corino 2003, p. 229)

- ↑ Corino 2003, pp. 257-261; Pfohlmann 2012, p. 50 f. Harry Graf Kessler was impressed by this and considered it “so far only” how in Törless “the motifs emerge from the subconscious, devour one another, grow past each other until the deed comes about”. (Quoted from Pfohlmann 2012, p. 47)

- ↑ Corino 1988, p. 142

- ↑ Pfohlmann 2012, p. 56 f. "For Musil the debacle of his volume of stories was a lifelong trauma, he would never again write so radically avant-garde." (Ibid., P. 58)

- ↑ Pfohlmann 2012, pp. 66–70.

- ^ Karl Corino: Robert Musil in the First World War - a picture find. Daredevils and tachiners . Neue Zürcher Zeitung, February 24, 2014, accessed on July 19, 2014

- ↑ Corino 2003, p. 541

- ↑ Nanao Hayasaka: Robert Musil and Bozen, the presumed setting of the novel "The Portuguese". In: Doitsu Bunka. Annual reports of the Society for German Culture and Language at Chuo University Tokyo No. 63, Tokyo 2008.

- ↑ Arno Kerschbaumer, Nobilitations under the reign of Emperor Karl I / IV. Károly király (1916-1921) , Graz 2016 ( ISBN 978-3-9504153-1-5 ), p. 61.

- ↑ Corino 2003, p. 591 f.

- ↑ Quoted from Pfohlmann 2012, p. 80.

- ↑ Pfohlmann 2012, p. 80 f.

- ↑ Corino 2003, p. 593 f.

- ↑ Pfohlmann 2012, p. 81 f.

- ^ Critique by Alfred Kerr in the Berliner Tageblatt, April 4, 1929, (online at: cgi-host.uni-marburg.de ) ( Memento of the original from June 13, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and still Not checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ "The proof that Die Schwärmer is not a mere reading, but a stage work that is still hard to beat for its liveliness and intellectual excitement, was only provided decades after Musil's death." (Pfohlmann 2012, p. 92)

- ↑ Pfohlmann 2012, p. 101.

- ^ Corino 2003, p. 1904.

- ^ Corino 2003, p. 950.

- ↑ Pfohlmann 2012, p. 116.

- ↑ Corino 2003, pp. 836 and 947.

- ↑ Quoted from Pfohlmann 2012, p. 108.

- ↑ Corino 1988, p. 382 f .; ders. 2003, p. 1917.

- ^ Corino 2003, p. 1121.

- ↑ Musil now lived permanently again at Rasumofskygasse 20, where a memorial room can be viewed today.

- ^ Corino 2003, p. 1156.

- ↑ The main advertiser for the Musil support group was Bruno Fürst, about whom Musil is said to have said: "Fürst will enter immortality through me." (Corino 2003, p. 1171)

- ↑ Quoted from Amann 2007, p. 246.

- ↑ Quoted from Amann 2007, p. 242.

- ↑ Corino 2003, pp. 1175 ff.

- ↑ Quoted from Amann 2007, p. 273.

- ↑ Quoted from Amann 2007, p. 275.

- ↑ Quoted from Corino 2003, p. 1230.

- ↑ Corino 2003, pp. 1925 ff.

- ↑ On the suggestion of Hans Mayer, for example, that Musil should try to get a visa in Colombia, he is said to have replied: " Stefan Zweig is in South America ." (Quoted from Pfohlmann 2012, p. 132)

- ↑ a b Pfohlmann 2012, p. 130.

- ↑ Robert Lejeune died . In: Arbeiter-Zeitung . January 13, 1971, p. 6, center right.

- ^ Robert Musil's difficult years in exile in Switzerland: Zurich, Pension Fortuna , nzz.ch, November 8, 2013

- ^ Wilhelm Genazino: A gift that goes wrong. About literary failure . In: German Academy for Language and Poetry: Yearbook . Volume 2002. Wallstein, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-89244-662-8 , ISSN 0070-3923 , p. 138. (online) , accessed on November 27, 2010.

- ↑ Corino 2003, p. 1443.

- ↑ Musil: Estate during his lifetime . Quoted from the Rowohlt edition, Reinbek, 24th edition 2004, p. 7 f.

- ↑ Musil: Estate during his lifetime . Quoted from the Rowohlt edition, Reinbek, 24th edition 2004, p. 8.

- ↑ Musil: Estate during his lifetime . Quoted from the Rowohlt edition, Reinbek, 24th edition 2004, p. 74.

- ↑ Musil: Estate during his lifetime . Quoted from the Rowohlt edition, Reinbek, 24th edition 2004, p. 75.

- ↑ Musil: Estate during his lifetime . Quoted from the Rowohlt edition, Reinbek, 24th edition 2004, p. 78.

- ↑ “Great art makes an exception to this, of course that which, strictly speaking, should only be called art. But that never really belonged in the society of the living. ”(Musil: Nachlass zu Lebzeiten . Quoted from the Rowohlt edition, Reinbek, 24th edition 2004, p. 82)

- ↑ Musil: Estate during his lifetime . Quoted from the Rowohlt edition, Reinbek, 24th edition 2004, p. 81.

- ↑ Quoted from Amann 2007, p. 142.

- ^ The Times, Literary Supplement, October 28, 1949

- ^ Horst Thomé: Weltanschauungsliteratur. Preliminary considerations on function and text type . In: Knowledge in Literature in the 19th Century . Niemeyer, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-484-10843-6 , p. 366 .

- ↑ Corino 2003, p. 19.

- ↑ Statutes and Board of Directors of the IRMG , accessed on September 15, 2017

- ↑ About Musil and Thomas Mann's enthusiasm for the war 1914–1918 and his vehement aversion to Heinrich Mann until after 1933.

- ↑ About Musil as an enthusiastic war propagandist 1914–1918

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Musil, Robert |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Musil, Robert Edler von (name before the nobility was abolished) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian writer and theater critic |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 6, 1880 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Klagenfurt |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 15, 1942 |

| Place of death | Geneva |