Alfred Doblin

Bruno Alfred Döblin (born August 10, 1878 in Stettin , † June 26, 1957 in Emmendingen ) was a German psychiatrist and writer .

His epic work includes several novels, short stories and short stories, he also wrote satirical essays and polemics under the pseudonym Linke Poot . As a leading expressionist and pioneer of literary modernism in Germany, Döblin integrated the radio play and script into his work early on . In 1920 he published the historical novel Wallenstein . Furthermore, Döblin continued as an avant-garde romantic theorist with the writings An Novel Authors and Their Critics. Berlin program , comments on the novel and the construction of the epic work free numerous impulses in the narrative prose. By far his most popular novel is Berlin Alexanderplatz .

Alfred Döblin came from a family of assimilated Jews. When he was ten years old, his father separated from his wife and left the family penniless. The sudden disappearance of the father traumatized the boy lastingly. In his last year of school, Döblin wrote several short stories and a short novel. After graduating from high school, he studied medicine , received his doctorate in 1905 and became an assistant doctor in psychiatry. In 1912 he married the medical student Erna Reiss.

The metropolis of Berlin became Döblin's actual home. He joined the Sturmkreis around Herwarth Walden . Döblin became one of the leading exponents of Expressionist literature with his volume of short stories The Murder of a Buttercup and other stories as well as the novels The Three Jumps of Wang-lun and Mountains, Seas and Giants . During the First World War he was stationed as a hospital doctor on the Western Front. During the Weimar Republic, the militant Döblin became one of the leading intellectuals on the left-wing bourgeoisie spectrum.

In 1933 the Jew and socialist Döblin fled Germany and returned after the end of the Second World War to leave Germany again in 1953. Large parts of his literary work, including the Amazon trilogy, the November tetralogy and the last novel Hamlet or The Long Night Comes to an End, are assigned to exile literature. In 1941 he converted to the Catholic faith, and in 1936 Döblin had already taken French citizenship.

Life

Origin and youth

Alfred Döblin came from a middle-class family of assimilated Jews. He was born in Stettin on August 10, 1878, the fourth child of Max and Sophie Döblin . As the daughter of a Jewish material goods dealer from Samter, his mother belonged to the wealthy class of Poznan, while his father's grandfather still spoke Yiddish as his mother tongue, but had lived in Szczecin since the early 19th century. Max Döblin (1846–1921), a cousin of the operetta composer Leon Jessel on his mother's side , was like his father Simon Döblin a master tailor by profession. After preselecting his parents, he married the wealthy Sophie Freudenheim (1844–1920). The dowry that was brought in financed the newly built clothing store and from then on ensured the family an above-average income. The family was able to counter the economic downturn that began after the early days of the company and forced Max Döblin to close down by opening a cutting room. In 1885 Döblin started school at the Friedrich Wilhelm School, a secondary school. Despite the boy's noticeable nearsightedness , who had to take a seat on the front bench while he was still in pre-school, the father refused to buy him a visual aid. In contrast to his siblings, including his older brother Hugo Döblin , Alfred Döblin was interested in literature very early on. In a certain way he was looking up his father, who played the piano and violin, drew and sang in the synagogue. His parents' marriage finally fell apart in June 1888; Max Döblin left his wife and four children for Henriette Zander, who was twenty years his junior, and with whom he emigrated to New York via Hamburg .

In the same year Sophie Döblin left Stettin with her children and moved to Berlin , where her brother Rudolf Freudenheim ran a furniture factory and the poor family could hope for further help. The Döblins initially lived on Blumenstrasse in the Friedrichshain district . The eldest son, Ludwig, began an apprenticeship in his uncle's company to help support the family. In Berlin, the family was exposed to greater poverty and anti-Semitism . "The Döblins belonged to the proletariat". In 1891 Döblin was again allowed to attend a school, the Kölln High School . Due to the previous moves and the lack of school fees, Döblin was already three years older than his classmates, and on top of that, his school performance fell sharply. The high school student began to be more interested in literature again. His readings included Kleist's dramas, Friedrich Hölderlin's Hyperion and his poems, Dostoyevsky's brothers Karamazov, and the philosophical works of Spinoza , Schopenhauer and Nietzsche . The 18-year-old integrated August Bebel's work Woman and Socialism in his prosaic attempt Modern (1986). In 1900, at the age of 22, he finally passed his Abitur and, influenced by Fritz Mauthner's skepticism about language and Arno Holz's naturalism , wrote the short novel Jagende Rosse .

Study of medicine

Döblin began studying medicine in Berlin, which he continued in Freiburg in 1904 and completed with Alfred Hoche's dissertation in 1905 with a dissertation on memory disorders in Korsakoff's psychosis . He became friends with Herwarth Walden and the poet Else Lasker-Schüler . During his student days he wrote several short stories, including the novella Murder of a Buttercup . Döblin found his first job at the Karthaus-Prüll District Insane Asylum in Regensburg . From 1906 to 1908 he worked in the Buch insane asylum in Berlin. There he fell in love with the sixteen-year-old nurse Frieda Kunke, who gave birth to their son Bodo Kunke in October 1911. In the meantime, Döblin published numerous psychiatric specialist texts. After 1908 he held the position of an assistant doctor in the Am Urban hospital , where he met his future wife, the medical student Erna Reiss (1888–1957). In 1911 Döblin officially ended the relationship with Frieda Kunke (1891–1918) and, like his father once, married Erna Reiss, a wealthy woman. He opened a cash practice in Berlin, his son Peter was born, the volume of short stories The Murder of a Buttercup and other stories appeared in November. In addition, the first romantic theoretical works were created. The relationship with Frieda Kunke continued secretly until her death, Döblin had regular contact with his eldest son and supported him financially. He resigned from the Jewish community and had his legitimate children registered as Christians before starting school. In 1913 he moved his practice to Frankfurter Allee 194 as an internist and neurologist.

expressionism

Writer and theorist

Döblin is considered to be the “most important expressionist novelist”, although his diverse work goes far beyond the epoch itself. The earliest narrative works such as Adonis and The Black Curtain are still indebted in terms of motif and material to the end of the fin de siècle era and influenced by Fritz Mauthner's criticism of language . The first avant-garde experimental narratives, The Dancer and the Body , The Sailing Trip and The Murder of a Buttercup, were to follow soon . In the magazine Der Sturm , founded by Herwarth Walden in 1910 , Döblin managed to publish his stories for the first time. At a Berlin Futurism exhibition in 1912 , he enthusiastically welcomed the new movement, only to distance himself from it a year later. Döblin had responded to Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's article Battle with sharp criticism in Walden's magazine. In his open letter "Futuristic Word Technique", he accused Marinetti that the destruction of syntax, the stubborn rejection of tradition and history and its one-dimensional concept of reality are insufficient for a new literature. The letter ended with the exclamation: “Cultivate your futurism. I cultivate my Döblinism. ”The French poet Guillaume Apollinaire replied :“ Long live Döblinism. ”Both shared the provocative poetic stance and a certain skepticism towards Italian futurism. Döblin took up the poetics of Marinetti and developed the expressionist means of design in this confrontation. The result was an eruptive style, which was created by turning away from the authorial narrative perspective , shortening language, personifying nature, dynamization, abandoning causal narrative patterns, smashing psychologism and the destruction of syntax borrowed from futurism such as the deletion of punctuation , which, however, in Döblin's case was moderate, is marked. In this way he finally succeeded in modernizing the German-language epic, free from the one-sidedness and dogmatism of the early avant-garde currents of the 20th century. With his 1913 essay To Novelists and Their Critics. In the Berlin program , he theoretically prepared the montage novel and designed an anti-bourgeois and anti- realistic poetics. From 1912 he worked on his novel Die Drei Sprünge des Wang-lun and published it after several attempts in 1916 by S. Fischer Verlag . The novel can be seen as Döblin's answer to Marinetti's 1909 work Marfarka the Futurist - African novel . The author not only achieved a literary breakthrough and recognition as an avant-garde writer, but also made an important contribution to the reception of China within German literature.

The First World War

In order to forestall a forced conscription to World War I, Döblin volunteered in 1914 and took sides with Germany early on. In his article Reims , which appeared in the Neue Rundschau in December 1914 , he himself justified the bombardment of the cathedral by German troops. During the war, Döblin served as a military doctor, mainly in an epidemic hospital in Saargemünd . In Lorraine he also began work on his novel Wallenstein . In 1915 Döblin's son Wolfgang Döblin was born, in 1917 their son Klaus. In August 1917 he left Saargemünd with his wife and children and moved to Hagenau . Döblin's transfer was preceded by a violation of the complaints procedure. In Hagenau he worked in two hospitals and carried out health checks on prisoners of war in June 1918. In August, the appointment as a war assistant was revoked . Doblin changed his attitude in the course of the war; If in February 1915 he sent a telegram to Walden with the message “hurray the russians in ink = heartily doeblin”, a year later he slowly began to revise his political views. If the deposition of the tsar had brought about the first change in Döblin, he showed with the article It's time! August 1917 sympathy for the Russian Revolution. On November 14th, Döblin and the hospital staff left Hagenau.

The Weimar Republic

In 1919 Döblin finished his novel Wallenstein , which appeared in two volumes a year later. Although the novel is set in the Thirty Years' War , it is shaped by “that terrible time”, the First World War. According to Peter Sprengel , the novel, published in 1920, is “directed against the positivist understanding of history of the 19th century”. In addition, according to Hans Vilmar Geppert, Döblins Wallenstein is "the first consistent example" of a historical novel of the modern age. After settling down as a doctor in the Lichtenberg district with his own cash practice, he became an eyewitness to the Berlin March fights in which his sister Meta Goldberg performed Shrapnel came to death. Later he was to thematize the confusion in his most extensive novel November 1918 . Döblin, who took sides for democracy shortly after the end of the war and joined the USPD in 1918 , wrote his first polemics in the Neue Rundschau under the pseudonym Linke Poot . In the sub-collection Der deutsche Maskenball , collected glosses and satires, published in 1921, he primarily criticized the political conditions of the Weimar Republic. “The republic was brought to the Holy Roman Empire by a wise man from abroad; He hadn't said what to do with it: it was a republic without instructions for use. ”Döblin affirmed democracy and, with his journalistic work, pursued an increase in democratic awareness within the population. In his essay From the Freedom of a Poet Man , published in 1918 in the Neue Rundschau , he clearly rejected Expressionism, which he understood as a movement: “Those who are devoted to the movement with body and soul become its martyrs. They are used up by the movement and then remain lying, crippled, disabled. ”Nonetheless, the novel Berge Meere und Giganten, begun in 1921 and published in 1924, with its numerous style experiments, such as the stringing together of nouns and verbs without punctuation or one from the novel Wallenstein ajar syntax, which is characterized by a sudden change of perspective, to the avant-garde of the first half of the century. Also in 1921 he met Charlotte Niclas (1900–1977), called Yolla by Döblin. The photographer became Döblin's long-time lover and inspired him to write his verse epic Manas . The youngest son Stephan was born in 1926.

After pogroms broke out in Berlin's Scheunenviertel in 1923, Döblin was confronted with his own Jewish origins. Three years earlier he had already expressed himself in a gloss of the Neue Rundschau from the standpoint of an assimilated Jew on anti-Semitism: “I once read that the Jews, as a dead people, made a ghostly impression and aroused fear of demons; hatred of Jews belongs deeper to the cultural-historical demonopathies, in a row and in the same mental one with fear of ghosts, belief in witches. ”Döblin, who was already interested in Yiddish theater, now began to occupy himself with Yiddish literature, accepted invitations to Zionist events and showed his solidarity with the Jews of Eastern Europe. In his 1924 lecture on Zionism and Western Culture , he insisted on the "autonomization of Eastern Jews" and traveled to Poland in the same year .

Döblin was one of the founders of the group in 1925 , an association of predominantly left-wing writers, artists and journalists. At the end of the Weimar Republic, the ideological frontline began to take hold of cultural life more and more. Döblin, who was appointed to the Poetry Section of the Prussian Academy of the Arts in 1928, represented a left-wing bourgeois position within the section together with Heinrich Mann .

Döblin characterized his own political attitude as a socialist in 1928:

“Sometimes it seems that he is definitely on the left, even very left, for example left to the power of two, then again he utters sentences that are either careless, which is absolutely inadmissible for a man his age, or pretend to be above the parties , smile in poetic arrogance. "

Around 1930 the union of proletarian revolutionary writers began to exclude left-wing bourgeois writers, to which the BPRS also Döblin belonged. In 1931 Döblin published the text Knowledge and Change , in which he spoke out against Marxism :

“I recognize the violence of the economy, the existence of class struggles. But I do not recognize that class and class struggle, these economic and political phenomena, proceed according to "physical" laws that are beyond human reach. "

In 1929 Döblin's best-known novel Berlin Alexanderplatz was published . The story of the cement worker Franz Biberkopf, who killed his girlfriend Ida, only wants to be decent and wants more from life than bread and butter, was one of the greatest successes of the Weimar Republic. The novel is considered the first and most important German-language city novel. As a key text of modernity, it found its way into schools and universities.

Years of emigration

Flight and Exile

One day after the Reichstag fire , the writer left Germany at the request of his friends and crossed the Swiss border on February 28, 1933. On March 3, his wife and sons Peter, Klaus and Stephan followed him to Zurich . In Switzerland, Döblin was not allowed to earn his living as a doctor, which is why he moved to Paris in September . Döblin's poor knowledge of foreign languages stood in the way of improving his predicament. The novel Babylonian Wandering or Arrogance Comes Before Fall , begun in 1932, was published by Querido Verlag in 1934 , but the grotesque did not bring the author financial success, and Döblin was not able to follow up on the previous work. A year later the novel Pardon is not given was published . The novel differs greatly from Döblin's narrative work; On the one hand, it is a novel in the tradition of bourgeois realism, which on top of that avoids any more modern style experiments; on the other hand, the story contains numerous autobiographical passages. In October 1936, he and his family took French citizenship .

When the war broke out , Döblin became a member of the Commissariat de l'Information , a French ministry for propaganda against the Third Reich , where he wrote leaflets , among other things . According to Dieter Schiller, Döblin wanted to contribute to the "fight against Nazism - of course also against Bolshevism, which he saw as its ally after the Hitler-Stalin Pact of August 1939". In 1937 Döblin's Die Fahrt ins Land ohne Tod , the first volume in the Amazon trilogy, was published . The work is a criticism of the colonization of South America and, according to the writer himself, is a "kind of epic general reckoning with our civilization". Shortly before the rapid invasion of the Wehrmacht , he fled with his wife and youngest son in Paris . The hasty escape - Döblin had crossed the towns of Moulins , Clermont-Ferrand , Arvant , Capdenac and Cahors before arriving in Le Puy on June 24, 1940 - led to the family separation. On July 10, the family reunited in Toulouse . Twenty days later she traveled to Lisbon and emigrated from Europe to the United States . They were able to move into a small apartment in Hollywood because Alfred Döblin got a job as a clerk at MGM . At George Froeschel's request , Döblin submitted suggestions for the design of one scene each for both the screenplay Oscar-winning film Mrs. Miniver (1942) and the Oscar-nominated Random Harvest (1942). Both times the successful scripts were translated into English and incorporated into the scripts - Döblin's draft scenes have been preserved. Nevertheless, his probationary year in 1941 at MGM ended without further employment. In 1943 Döblin finished his November tetralogy . The impoverished writer received support from the Writers Fund , the writer Lion Feuchtwanger and from Jewish organizations, from which Döblin had to keep his conversion secret.

Conversion to the Catholic Faith

On November 30, 1941 Döblin was baptized together with his wife and son Stephan in the Blessed Sacrament Church . The conversion was preceded by a revival in Mende Cathedral in 1940 . At the celebration of his 65th birthday, Döblin confessed to almost two hundred guests, including numerous exiled writers, in a speech on Christianity and denounced moral relativism. Bertolt Brecht who was present later even reacted to Döblin's conversion with his own poem, entitled “Embarrassing Incident”. Gottfried Benn mocked: “Döblin, once a great avant-garde, and Franz Biberkopf from Alexanderplatz, became strictly Catholic and proclaimed Ora et labora.” The reason for the strict rejection, even by former companions like Brecht, who could only classify Döblin's conversion as the result of a terrible escape , according to Karl-Josef Kuschel, the idea that has prevailed since the Enlightenment is of a dichotomy between art and religion: "Anyone who has become religious is eliminated as an artist to be taken seriously."

Return to Europe

Döblin was one of the first exiled authors to return to Europe. On October 15, he and Erna Döblin reached Paris. In March 1945 they found out about the whereabouts of their second eldest son, Wolfgang (Vincent). The mathematician had taken part in the Second World War as a French soldier and shot himself in Housseras in 1940 just before the imminent capture by German troops. The widow of his brother Ludwig and their daughter as well as the youngest brother Kurt Viktor and his wife were deported to Auschwitz and murdered. In November Döblin began his service as literary inspector of the French military administration - with the rank of colonel - first in Baden-Baden and later in Mainz . There he was one of the founders of a literary class at the Academy of Sciences and Literature . His duties included the censorship of manuscripts and the preparation of a literary monthly magazine that eventually appeared under the name The Golden Gate . He also wrote for the Neue Zeitung and the Südwestfunk . The book Der Nürnberger Lehrprozess , a reaction to the Nuremberg trials , published in 1946 under the pseudonym Hans Fiedeler , contains sharp observations on the historical dimension of the court hearings: “It cannot be repeated often enough and not joyfully enough: it works with the re-establishment of the law in Nuremberg about the restoration of mankind, to which we also belong. ”In addition to the enlightenment, Döblin strived for a catharsis of the Germans:“ They subjected us and drove us to bad things that the shame will lie on us for a long time. We know it. We do not deny it. [...] We atone. We have to pay more. Let's finally step into our seat. Let us point out men who proclaim to the world that morality and reason are as safe with us as with other peoples. ”Döblin finished his novel Hamlet or The Long Night Takes One in Baden-Baden, which he began in 1945 in Los Angeles , and tried to continue his interrupted literary career through rapid pressure from exile works.

Late work and renewed emigration

The Alber Verlag won Doblin finally for the pressure of his extensive narrative work November 1918 , whose literary success, however small precipitated. Serious reception only began with the paperback edition of the novel in 1978. The literary scholar Helmuth Kiesel sums up: “The history of Alfred Döblin's effectiveness in post-war Germany is unfortunate. It began with misunderstandings and continued with misjudgments which have not yet been cleared up and which still stand in the way of adequate consideration of his exile and late work. ”During his work as a cultural officer, Döblin assumed that he could work as a re-educator in the reorganization of Germany , is even needed, in order to ultimately only come across the “denial of the reign of terror” and “repression of feelings of guilt”. As early as 1946 he commented on his attempt to regain a foothold in the Federal Republic: "And when I came back - I never came back."

Johannes R. Becher's advances in the service of the Academy of the Arts in the GDR were rejected because of “socialist dogmatism”, although he was promised an academic salary next to a house. On the other hand, he wrote articles for GDR magazines, and his Hamlet novel could initially only appear in the GDR. 1953 Döblin left the Federal Republic and went back to France.

Because of the progressive Parkinson's disease , he had to be treated more and more frequently in clinics and sanatoriums, including in Höchenschwand and Buchenbach in the southern Black Forest and in Freiburg im Breisgau . During his last stay in a clinic in Emmendingen , he died on June 26, 1957. Döblin was buried next to his son Wolfgang in the Housseras cemetery in the Vosges Mountains . His wife Erna committed suicide in Paris on September 14, 1957 and was buried next to her husband and son.

Literary work

With the exception of poetry, Döblin tried his hand at numerous literary genres in his work . In addition to novels, short stories, short stories and the verse epic Manas, he also wrote a few dramas, several essays and two travelogues. Despite the relative breadth of his literary oeuvre, Döblin's literary achievement lies primarily in the epic and isolated, predominantly poetological essays. The plays Lusitania and The Marriage sparked a theatrical scandal, but Doblin's plays did not go beyond provoking the bourgeois audience. The fact that the narrator Döblin dealt with the theater at all was less due to himself than to the importance of theater for the social and literary life of the Weimar Republic at the time. It was here that writers such as Frank Wedekind and Carl Sternheim criticized society, and it was here that one met the avant-garde in the form of expressionist, later epic theater . Despite well-known advocates such as Robert Musil and Oskar Loerke, the epic Manas did not get much response. Recently, his natural philosophy has received greater attention in literary studies. In addition, research is now seriously examining Döblin's religious writings.

Epic

Wrote already during his school days Doblin the short novel Jagende Rosse , a "lyrical first-person novel," which he called "the manes Hölderlin was in love and devotion dedicated". Based on the language skepticism at the beginning of the 20th century, Döblin wrote his second short novel The Black Curtain on the slide of Goethe's Werther , in which the protagonist Johannes commits a lust murder of his girlfriend. The enthusiastic dedication to Hölderlin and the celestial motif of cannibalistic love correspond to Döblin's modernistic gesture, which is directed against the common conventions of bourgeois literature. It is noticeable that Döblin's texts, which were written around the turn of the century and were not intended for the literary public, differ greatly in style and theme. Döblin's first creative period finally came to an end with the publication of his first volume of short stories The Murder of a Buttercup and other stories . The choice of motifs, fabrics and figures suggests a closeness to the fin de siècle , which is why Walter Muschg came to the judgment that Döblin was still subject to the “mood magic of symbolism” and at that time “not yet the spokesman for the naturalistic, socialist art revolution for which he violently entered after the First World War ”. Matthias Prangel, on the other hand, writes about the eponymous novella: " Psychopathology and literature were linked up until then only in Georg Büchner's ' Lenz ', which Döblin no longer gave up." Consequently, "Döblin's efforts to find suitable literary means of expression [...] to be understood in their beginnings not least in - albeit critical - examination of the aesthetic currents of the turn of the century. "

In 1911, Döblin finally turned to large-scale literary forms. The main works are the three jumps of Wang-lun , the historical Roman Wallenstein and Berlin Alexanderplatz . With his debut from the Chinese rebel and founder of the Wu-wei sect Wang-lun , Döblin achieved the “breakthrough through the bourgeois tradition of the German novel”. In 1918 the grotesque Wadzek's Battle with the Steam Turbine appeared , in which the factory director Franz Wadzek was defeated in a bitter, but hopeless competition. The business novel was often received as a preliminary step to Berlin Alexanderplatz because of the poeticization of city life . In his historical novel Wallenstein , Döblin took a socio-historical standpoint towards the heroic narrative of the great individual and attacked the objectivity postulate of historicism by deconstructing the story in relation to the Thirty Years War as a meaningful authority and revealing the political motives of such a narrative. The novel represents a turning point in the genre of the historical novel because it ushered in the modern age in the historical novel, just as modern fiction as such pushed through numerous technical innovations. The dystopia of mountains, seas and giants represents a turning point in Döblin's oeuvre through the re-evaluation of the individual. The bulky work combines disparate sources into an 800-year history of humanity. In 1929 the novel was published, which is considered Döblin's most important contribution to world literature and which was to become a “founding document for literary modernism”: Berlin Alexanderplatz .

Döblin continued his writing activity in exile. The begun in Berlin burlesque novel Babylonian Wandrung or pride comes before the fall sets Doblin first literary examination of his escape from the Third Reich . A year later, the partially autobiographical novel quarter will be given published in Doblin the failure of the democratic revolution of 1918 tells how its social and historical causes, illustrated by the biography of a single protagonist. Written between 1935 and 1937, the Amazon trilogy appeared under the titles Die Fahrt ins Land ohne Tod , The Blue Tiger and The New Primeval Forest until 1948 . In comprehensive than 2,000 pages narrative work November 1918. A German Revolution , a trilogy or tetralogy about the failed November Revolution , Doblin tells the history of the two returning comrades Friedrich Becker and John mouse and the failure of social democratic government and the inability of revolutionaries in January To use the chance for a revolution in 1919. The cycle falls between the genres of historical novels and religious epics. Döblin's last novel Hamlet or The Long Night Comes to an End deals with the search for the war guilt that a wounded soldier imposes on his surroundings.

According to Klaus Müller-Salget, Döblin's novels and stories are characterized by a suggestive “handling of the varying repetition” and the “virtuoso alternation of external and internal views, of narrative reports, internal monologues and experienced speech”. In his literary work he combines medical, psychiatric, anthropological, philosophical and theological discourses. His heroes are usually male anti-heroes. The individual is displaced in favor of collectivism, thus deviating from the concept of the action-carrying protagonist. However, there is no dismantling of the individual, but the human being is seen essentially in connection with nature or technology.

Novel poetics

Döblin's novels always went hand in hand with poetological reflection. The aim, however, was not to draft a strict novel poetics, but to deal with one's own aesthetic project. This explains the timely appearance of his writings with the novels: To novelists and their critics. The Berlin program was published two years before The three jumps of Wang-lun , the remarks on the novel three years before Wallenstein , The construction of the epic work one year before Berlin Alexanderplatz and The historical novel and we one year before the first volume of the Amazon trilogy .

The Dialogue Conversations with Kalypso. About the music appeared in 1910 in the storm . Nietzsche's strong influence is evident in his rejection of an art that, like aestheticism, is lost in the game, or is exhausted in mere imitation of the world. Although readable as a music-theoretical work, Döblin represents the totality claim of modern literature, which includes constant reflection on the origin of the text and the role of the author. Furthermore, he tries to make Richard Wagner's romantic musical conceptions of an infinite melody as an expression of an unlimited will to live, critically fruitful for prose.

In his newspaper article Futuristic Word Technique. In an open letter to Marinetti from 1913, he praised the attack by the futurists on the dominant aestheticism and called for a resolute turn to the facts: “Naturalism, naturalism; we are still far from enough naturalists. ”Döblin, however, distanced himself from the destruction of syntax, in which he saw the abolition of a meaning established by signs, which ultimately ran counter to the epic narrative and acknowledged objectivity . In the Berlin program , published in May 1913, he radicalized his rejection of the psychologizing novel and called for the author to be renounced, for the use of a desreptive representation trained in psychiatry, in which no reduction in motifs was pursued, and for the permanent narrative authority to be given up in favor of one Depersonalization and assembly produced polyperspectivity. His much-quoted poetological statement comes from the text Comments on the Roman (1917): “If a novel cannot be cut into ten pieces like an earthworm and each part moves itself, then it is no good”. Döblin attacked the contemporary tendency in the novel, according to which a single conflict-laden fact was raised to the subject of the epic and whose exciting development continues the plot. Rather, epic literature - probably in memory of his reading of Guilt and Atonement - should open itself to the topics of trash literature in order to find new stimuli than to pursue the novelistic design of erotic conflicts. In formal terms, this means a merging of individual actions, languages and the participation in discourses in a superordinate current event, which he ties in with his writing Conversations with Calypso .

The construction of the epic work is Döblin's most important contribution to novel poetics. In his speech, art is not free, but effective. Ars militans held at the Berlin Academy on May 1929, Döblin advocated a re-evaluation of art in public. He valued artistic freedom as the state's silent approval of the social ineffectiveness of art, which is based on the privileged access of an anti-revolutionary class to art. In the same year he wrote the speech Literature and Radio , in which he emphasized the importance of the new medium radio for literature from a media aesthetic perspective. In 1930 his work From Old to New Naturalism was published. In June 1936 his last important work on novel poetry appeared with The historical novel and we .

Travel literature

Doblin was not a traveler. Berlin remained the center of his life and work, from which his expulsion in 1933 wrested him. Nevertheless, external circumstances led to the writing of travel reports. After he was won over by Berlin Zionists for a trip to Poland, he went to re-established Poland for two months in autumn 1924. The resulting work Reise in Polen aroused the interest of research , especially because of the Eastern Jewish life, to which he devoted almost a hundred pages in the chapter The Jewish City of Warsaw . According to Marion Brandt, Döblin's descriptions are of great value due to the destruction of Eastern Jewry in Poland. His second work, Die Schicksalsreise deals with one's own exile experience and conversion to Catholicism.

reception

meaning

Klaus Müller-Salget counts Alfred Döblin among the "undoubtedly most fruitful and original German prose authors" of the 20th century. Peter Sprengel calls him "one of the strongest narrative talents of the 20th century". Helmuth Kiesel summarizes: “With his early stories (“ The Murder of a Buttercup ”), with his poetological program writings (such as the open letter to the futurist Marinetti) and with some of his novels, he belongs to the top group of German-speaking authors of the twentieth century. “Together with Bertolt Brecht and Gottfried Benn , Döblin is considered to be a representative of a reflected modernism in Germany, who adopted literary techniques of the avant-garde, but rejected their one-sidedness and dogmatism. The city novel Berlin Alexanderplatz can be seen as the result of this fruitful discussion . With regard to this novel, Christian Schärf judges that Döblin was “undoubtedly the most radical innovator of the modern novel in Germany before the Second World War”. The historical novel Wallenstein is one of the first historical novels of the 20th century, which tackled the immediate German past, here the First World War, in perspective, as Lion Feuchtwanger later did with Jud Süß in relation to the rampant anti-Semitism of the Weimar Republic or Heinrich Mann in The Youth of King Henri Quatre should do because of the obviously destroyed Europe. Furthermore, the expressionistic novel finally broke with the dominance of historical novels in the tradition of the 19th century and, through its immanent criticism of history, represented a rejection of the ideologization of the historical novel as it was practiced by völkisch authors at the beginning of the century. As one of the few great historical novels in the German language of the 20th century, the novel was very well received by a subsequent generation of writers, as it gave up realistic representation in favor of modern stylistic devices and narrative methods.

Viktor Žmegac judges Döblin's poetics: “Although formulated with particular verve, Döblin's programs and diagnoses at the time could not make themselves heard more than most of the texts in the flood of futuristic and expressionistic manifestos. Today we see that he with his writings not only an individual - has designed poetics, but that he is now also been forecasters key trends in the novel of the century "Helmuth Kiesel says that the essay - and practiced. The construction of the epic work "Probably the most important novel poetics of the modern age".

Reception history

Contrary to Döblin's literary importance, the distribution of his work, with the exception of Berlin Alexanderplatz and early stories, remained low for a long time. Oliver Bernhardt called him a "forgotten poet". When he returned home as a French cultural officer and Catholic, he upset the literary business, as did many fellow writers. In the year of his renewed emigration he wrote to Theodor Heuss : “After seven years, now that I am giving up my domicile in Germany, I can sum up: it was an instructive visit, but I am in this country where I and my parents are born superfluous ”. After Thomas Mann had already received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929 and later his “Spezi” Hermann Hesse in 1946, he expressed himself with biting mockery: “I've been as much as the boring Hermann Hesse lemonade for a long time.” Döblin himself was suggested several times for the award, last indirectly in 1957 by Ludwig Marcuse , but never received it. How big the gap has become between Döblin and German post-war society can already be seen from the fact that the magazine with the highest circulation, Der Spiegel , made the temporary National Socialist Heimito von Doderer, after the death of the authors Mann, Brecht and Benn, the highest representative of the German literature had chosen.

With the annotated edition of works by Walter Verlag, founded in 1960, Döblin's novels were completely available again. The editor and Swiss literary scholar Walter Muschg recalled the expressionist generation and above all its most important narrator Döblin, but he largely devalued Döblin's late work for this, for example in the case of the grotesque Babylonian Wandering or Arrogance comes before the fall, he made several cuts and only published the first two volumes of the Amazon Trilogy. Even the generation of 68 was unable to reconcile with the intellectual revolutionaries, critical socialists and later Catholics. In Lukác's tradition, Sebald criticized the last novel as glorifying violence and irrational. According to Bernhardt, a change can be observed since the 1970s, among other things thanks to exhibitions and editions which allow biographical access to the work. The literary reception was initially limited to the early and major works, but with the founding of the International Alfred Döblin Society in 1984 , at the latest, a change began and the later work and its journalism moved into the focus of Germanists.

influence

Döblin's narrative work exerted influence on his fellow writers during his lifetime. Bertolt Brecht emphasized his artistic fertilization through Döblin: “I learned more from Döblin than from anyone else about the essence of the epic. His epic and even his theory about epic has strongly influenced my drama and his influence can still be felt in English, American and Scandinavian dramas, which in turn are influenced by mine. ” Lion Feuchtwanger saw his epic form primarily influenced by Döblin.

Döblin's influence on German storytellers after 1945 was almost unprecedented. In a text written in 1967, Günter Grass emphatically acknowledged his “teacher” Alfred Döblin. The reason he later cites the radical modernity of Döblin, who has developed new possibilities of prose in each of his books. Wolfgang Koeppen expressed himself similarly, he counted Döblin next to Marcel Proust , James Joyce and William Faulkner to those "teachers of the craft" who opened up new stylistic possibilities for his generation of writers. Arno Schmidt , who called Döblin the “church father of our new German literature”, was one of those German-speaking storytellers who continued the modernist prose practiced by Döblin in Germany after 1945, instead of following American models like most of the authors To recur Ernest Hemingway . Other German-speaking storytellers such as Wolfdietrich Schnurre or Uwe Johnson as well as the poet Peter Rühmkorf received important suggestions for their literary renewal from reading Döblin. Even W. G. Sebald , who in his dissertation The Myth of Destruction in Döblin's Work, unjustifiably suspected Döblin of having prepared National Socialism through a drastic depiction of violence and apocalyptic narrative, could not free himself from Döblin's effect. When the contemporary writer Uwe Tellkamp asked in his Leipzig poetics lecture whether the novel could develop into an epic again, he fell back, without knowing it, to Döblin's idea of the novel as an epic of modernity. Ingo Schulze, on the other hand, praised the stylist Döblin's ability to transform.

Comments about Döblin

“This Left Poot tickles with the foil where Heinrich Mann happened - and he has more wit than the whole Prussian brutality, and that means something. He deals with the new Germany gently, concisely, with fun, "shamelessly" and fervently. It's a completely new kind of joke that I've never read in German. "

"There are very few people who can finish reading Döblin's books, but very many buy them and everyone is somehow certain that Döblin is a great narrator, although they have to admit that it is terribly difficult to listen to."

"D. is, as I said, a gigantic epic. He makes art with his right hand, and with the little finger of his right hand he does more than almost any other novelist. "

“The style-defining influence that Döblin exerted on the narrative style of German novelists after 1945 can only be compared with that of Kafka : Wolfgang Koeppen and Arno Schmidt , Günter Grass , Uwe Johnson and Hubert Fichte - they all come to one word from Dostoyevsky about Gogol to use from his coat. "

“Döblin was wrong. He didn't arrive. For the progressive left it was too Catholic, for the Catholics too anarchic, for the moralists it denied tangible theses, too inelegant for the night program, it was too vulgar for the school radio; neither the 'Wallenstein' nor the 'Giants' novel could be consumed; and the emigrant Döblin dared to return home in 1945 to a Germany that soon devoted itself to consumption. So much for the market situation: the Döblin value was and is not listed. "

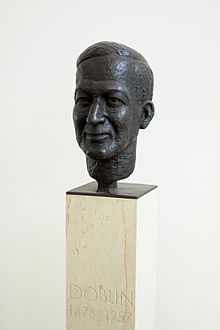

Honors

For his novel The Three Jumps of Wang-lun , which marked Döblin's literary breakthrough, he was awarded the Fontane Prize in 1916 . In 1954 he received the Literature Prize of the Academy of Sciences and Literature Mainz , in 1957 the Great Literature Prize of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts . Shortly after his 100th birthday, on September 11, 1978, the triangle formed by the Luckauer, Dresdener and Sebastianstraße in Berlin-Kreuzberg received his name. In 1979 Günter Grass donated the Alfred Döblin Prize . In 1992 the city of Berlin set up a bronze bust of Siegfried Wehrmeister on Karl-Marx-Allee . Due to theft, the Neuguss was set up in the foyer of the district central library at Frankfurter Allee 14a. A commemorative medal was placed on the house where he was born in Szczecin. In 2003 a Berlin plaque was unveiled on his house in Berlin-Charlottenburg . In 2007 Stephan Döblin opened Alfred-Döblin-Platz in the Freiburg district of Vauban . The Academy of Sciences and Literature Mainz has awarded the Alfred Döblin Medal since 2015.

Works (selection)

Novels

- The three leaps of the Wang-lun . A Chinese novel. 1916.

- Wadzek's fight with the steam turbine. 1918. ( en )

- Wallenstein . 1920.

- Mountains, seas and giants . Roman 1924. (abbreviated in 1932 and d. T .: Giganten. )

- Berlin Alexanderplatz . Novel. German first edition. S. Fischer Verlag, Berlin 1929.

- Babylonian migration. Novel. 1934.

- Pardon is not given. Novel. 1935.

- Amazon. Novel trilogy. 1937/38.

-

November 1918. A German revolution . Narrative work in four volumes 1948/1949/1950. Relaunched:

- November 1918. A German revolution. , Part 1: Citizens and Soldiers 1918 . Fischer-Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-596-90468-6 .

- November 1918. A German revolution. , Part 2, Volume 1: Betrayed People . Fischer-Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-596-90469-3 .

- November 1918. A German revolution. , Part 2, Volume 2: Return of the Front Troops . Fischer-Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-596-90470-9 .

- November 1918. A German revolution. , Part 3: Karl and Rosa . Fischer-Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-596-90471-6 .

-

Hamlet or The Long Night comes to an end . Novel. 1956.

- Newly published by Christina Althen and Steffan Davies: Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2016, ISBN 978-3-596-90472-3 .

stories

- The Assassination of a Buttercup and Other Tales . Narrative volume. 1913.

- The Lobensteiners travel to Bohemia. Narrative volume. 1917.

- The two friends and their poisoning . Narrative. 1924.

- Feldzeugmeister Cratz. The chaplain. Stories. Weltgeist, Berlin 1927 (the 1st arch. Again in: New German narrators. Volume 1 ( Max Brod and others) Paul Franke, Berlin undated (1930)).

- The Colonel and the Poet or The Human Heart. Narrative. 1946.

- The pilgrim Aetheria. Narrative. 1955.

Epic, libretto and plays

- Manas. Versepos (elaboration of a motif from ancient Indian mythology , especially the story of Savitri and Satyavan ) 1927.

- Lydia and Maxchen. Play. Premiere December 1, 1905 Berlin.

- The nuns of Kemnade. Play. Premiere April 21, 1923 in Leipzig.

- Lusitania. Play. Premiere January 15, 1926 Darmstadt.

- Marriage. Play. Premiere November 29, 1930 in Munich.

- The water. Cantata. Music: Ernst Toch . Premiere June 18, 1930 Berlin.

Essays

- Conversations with Kalypso. About the music. 1910.

- Futuristic word technique . Open letter to FT Marinetti. 1913.

- To novelists and their critics. Berlin program . 1913.

- Comments on the novel . 1917.

- The construction of the epic work . 1928.

- The self above nature. 1928.

- Literature and radio . 1929.

- Art is not free but effective. Ars militans . 1929.

- Our existence. "Intermediate texts" 1933.

- The immortal man, a religious conversation. 1946.

- The Nuremberg teaching process. 1946.

- The Presents of Literature. 1947.

Travel reports

- Trip in Poland . Report. 1925.

- Alfred Döblin - My address is: Saargemünd, searching for traces in a border region. 1914-1918. Compiled and commented on by Ralph Schock . Gollenstein Verlag, Merzig 2010, ISBN 978-3-938823-55-2 .

- Journey of fate . Report and confession. Publishing house Joseph Knecht, Frankfurt am Main 1949.

PhD thesis

- Memory disorders in Korsakoff's psychosis . Tropen, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-932170-86-5 (dissertation, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, 1905).

Magazine articles

- Against the culture reaction! Against the abortion law! For Friedrich Wolf! In: The Socialist Doctor . Volume VII, Issue 3, March 1931, p. 65 f. (Digitized version) .

Work edition

Selected works in individual volumes / Justified by Walter Muschg. In connection with the poet's sons, ed. by Anthony W. Riley and Christina Althen, Olten u. a .: Walter, 1960-2007.

- Hunting horses. The black curtain and other early narratives. 1981, ISBN 3-530-16678-2 .

- The three jumps of Wang Lun. Chinese novel, ed. by Gabriele Sander and Andreas Solbach. 2007, ISBN 978-3-530-16717-7 .

- Wadzek's fight with the steam turbine. Novel. 1982, ISBN 3-530-16681-2 .

- Wallenstein. Novel. Edited by Erwin Kobel. 2001, ISBN 3-530-16714-2 .

- Mountains, seas and giants. Novel. Edited by Gabriele Sander. 2006, ISBN 3-530-16718-5 .

- Berlin Alexanderplatz. The story of Franz Biberkopf. Edited by Werner Stauffacher. 1996, ISBN 3-530-16711-8 .

- Babylonian wandering or arrogance comes before the fall. Novel. 1962, ISBN 3-530-16613-8 .

- Pardon is not given. Novel. 1960, ISBN 3-530-16604-9 .

-

Amazon.

- Amazon, 1. The land without death. Edited by Werner Stauffacher. 1988, ISBN 3-530-16620-0 (complete ISBN for volumes 1–3).

- Amazon, 2. The blue tiger. Edited by Werner Stauffacher. 1988.

- Amazon, 3. The new jungle. Edited by Werner Stauffacher. 1988.

-

November 1918: a German revolution. Narrative work in three parts. Edited by Werner Stauffacher.

- 1. Citizens and soldiers 1918. With an introduction to the narrative. 1991, ISBN 3-530-16700-2 . (Complete ISBN for volumes 1–3).

- 2.1 People betrayed. Based on the text of the first edition (1949), with a “prelude” from “Citizens and Soldiers 1918”, 1991.

- 2.2 Return of the front troops. Based on the text of the first edition (1949), 1991.

- 3. Karl and Rosa. Based on the text of the first edition (1950), 1991.

- Hamlet or The Long Night comes to an end. Novel. 1966, ISBN 3-530-16631-6 .

- Manas. Epic poetry. 1961, ISBN 3-530-16610-3 .

- The colonel and the poet or the human heart. The Pilgrim Aetheria, 1978, ISBN 3-530-16660-X .

- The murder of a buttercup. All the stories. Edited by Christina Althen, 2001, ISBN 3-530-16716-9 .

- Drama, radio play, film. 1983, ISBN 3-530-16684-7 .

- Writings on aesthetics, poetics and literature. Edited by Erich Kleinschmidt . 1989, ISBN 3-530-16697-9 .

- Writings on life and work. Edited by Erich Kleinschmidt. 1986, ISBN 3-530-16695-2 .

- Writings on politics and society. 1972, ISBN 3-530-16640-5 .

- Writings on Jewish Issues. Edited by Hans Otto Horch u. a. 1995, ISBN 3-530-16709-6 .

-

Small fonts.

- Small writings, 1. 1902–1921. 1985, ISBN 3-530-16687-1 .

- Small writings, 2. 1922–1924. 1990, ISBN 3-530-16689-8 .

- Small writings, 3. 1925–1933. 1999, ISBN 3-530-16691-X .

- Small writings, 4. 1933–1953. Edited by Anthony W. Riley et al. a. 2005, ISBN 3-530-16692-8 .

- The German masked ball. [Fischer, 1921] By Linke Poot. Knowledge and change !, 1972, ISBN 3-530-16643-X .

- Our existence. 1964, ISBN 3-530-16625-1 .

- Criticism of the time. Broadcasts 1946–1952. In the appendix: Contributions 1928–1931, 1992, ISBN 3-530-16708-8 .

- The Immortal Man: A Religious Discussion. The fight with the angel: religious conversation (a walk through the Bible). 1980, ISBN 3-530-16669-3 .

- Trip in Poland. 1968, ISBN 3-530-16634-0 .

- Journey of Fate : Report and Confession. 1993, ISBN 3-530-16651-0 .

- Letters 1. 1970, ISBN 3-530-16637-5 .

- Letters, 2nd ed. By Helmut F. Pfanner. 2001, ISBN 3-530-16715-0 .

In addition, the following volumes have been published, which have been replaced by the above:

- The three jumps of Wang Lun. 1960. Replaced by Volume 2.

- Berlin Alexanderplatz. 1961. Replaced by Volume 6.

- The murder of a buttercup. 1962. Replaced by Volume 14.

- Amazon. 1963 Replaced by Volume 9.

- Essays on literature. 1963. Replaced by Vol. 16, 17, 20.2-20.4, 27, 28.

- Wallenstein. 1965. Replaced by Volume 4.

- Mountains, seas and giants. 1978. Replaced by Volume 5.

- Stories from five decades. 1979. Replaced by Volume 14.

- Autobiographical Writings and Recent Records. 1980. Replaced by Volumes 17 and 26.

The following volumes were still planned, but due to the change of publisher to S. Fischer in 2008, they no longer appeared in the edition:

- The self above nature. Our concern.

- Censorship report after World War II.

estate

Döblin's estate is in the German Literature Archive in Marbach . Parts of the estate can be seen in the permanent exhibition in the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach, in particular the manuscript for Berlin Alexanderplatz .

literature

Monographs

- Heinz Ludwig Arnold : Alfred Döblin. (= Text + criticism . Strap 13/14). 2nd Edition. edition text + kritik, Munich 1972, ISBN 3-921402-81-6 .

- Oliver Bernhardt: Alfred Döblin and Thomas Mann. A checkered literary relationship. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8260-3669-9 .

- Sabina Becker: Döblin manual. Life - work - effect. JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2016, ISBN 978-3-476-02544-9 .

- Roland Dollinger, Wulf Koepke, Heidi Thomann Tewarson (eds.): A Companion to the Works of Alfred Döblin. Camden House, Rochester 2004, ISBN 1-57113-124-8 .

- Ulrich Dronske: Deadly presences. On the philosophy of the literary in Alfred Döblin. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1998, ISBN 3-8260-1334-4 .

- Birgit Hoock: Modernity as a paradox. the term "modernity" and its application to the work of Alfred Döblin (until 1933). Niemeyer, Tübingen 1997, ISBN 3-484-32093-1 .

- Louis Huguet: Bibliography Alfred Döblin. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin / Weimar 1972.

- Thomas Keil: Alfred Döblin's “Our Dasein”. Source philological studies. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2005, ISBN 3-8260-3233-0 .

- Helmuth Kiesel: literary grief work. Alfred Döblin's exile and late work. Gruyter, Tübingen 1986, ISBN 3-484-18089-7 .

- Erwin Kobel: Alfred Döblin. Narrative art in upheaval. Gruyter, New York 1985, ISBN 3-11-010339-7 .

- Wulf Koepke: The Critical Reception of Alfred Döblin's Major Novels. Camden House, New York 2003, ISBN 1-57113-209-0 .

- Paul EH Lüth (Ed.): Alfred Döblin. For the 70th birthday. Limes, Wiesbaden 1948 (commemorative publication).

- P. Lüth: Alfred Döblin as a doctor and patient. Stuttgart 1985.

- Burkhard Meyer-Sickendiek : What is literary sarcasm? A contribution to German-Jewish modernity. Fink, Paderborn / Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-7705-4411-0 .

- Jochen Meyer (in collaboration with Ute Doster): Alfred Döblin. 1878-1988. An exhibition of the German Literature Archive in the Schiller National Museum, Marbach am Neckar from June 10th to December 31st. 4th, modified edition. German Schiller Society, Marbach 1998, ISBN 3-928882-83-X (catalog).

- Marily Martínez de Richter (ed.): Modernity in the metropolises. Roberto Arlt and Alfred Döblin. International Symposium, Buenos Aires - Berlin 2004. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2005, ISBN 3-8260-3198-9 .

- Matthias Prangel: Alfred Döblin. Metzler, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-476-12105-4 .

- Klaus Müller-Salget: Alfred Döblin. Factory and development. Bouvier, Bonn 1972, ISBN 3-416-00632-1 .

- Gabriele Sander: Alfred Döblin. Reclam, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-15-017632-8 .

- Simonetta Sanna: Dying yourself and becoming whole: Alfred Döblin's great novels. Lang, Bern 2003, ISBN 3-906770-74-5 .

- Ingrid Schuster, Ingrid Bode (Ed.): Alfred Döblin in the mirror of contemporary criticism . Francke, Bern 1973, ISBN 3-7720-1063-6 .

- Pierre, Kodjio Nenguie: Interculturality in the work of Alfred Döblin (1878–1957): Literature as a deconstruction of totalitarian discourses and a draft of an intercultural anthropology Paperback - November 14, Ibidem 2005 edition 1, ISBN 3-89821-579-2 .

- Sabine Kyora: Alfred Döblin. (= Text + criticism . Strap 13/14). New version. 3. Edition. edition text + kritik, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-86916-759-6 .

Biographies

- Armin Arnold: Alfred Döblin. Morgenbuchverlag, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-371-00403-1 .

- Oliver Bernhardt: Alfred Döblin. Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-423-31086-4 .

- Roland Left: Alfred Döblin: Life and Work. People and Knowledge, Berlin 1965.

- Marc Petit: The lost equation. In the footsteps of Wolfgang and Alfred Döblin. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-8218-5749-8 .

- Wilfried F. Schoeller : Döblin - A biography. Hanser, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-446-23769-8 .

- Klaus Schröter : Döblin. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1978, ISBN 3-499-50266-6 .

Essays

- Christina Althen: Alfred Döblin. Work and effect. In: Pommersches Jahrbuch für Literatur 2. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-55742-6 , pp. 219–226.

- Christina Althen: "A look at the literature saves some x-rays". Doctor Alfred Döblin. In: Harald Salfellner (Ed.): With pen and scalpel. Crossing the border between literature and medicine. Vitalis, Prague 2013, ISBN 978-3-89919-167-7 , pp. 353-375.

- Thomas Anz: "Modern becomes modern". Civilizational and aesthetic modernity in Alfred Döblin's early work. In: International Alfred Döblin Colloquium Münster. Bern 1993, pp. 26-35.

- Thomas Anz: Alfred Döblin and psychoanalysis. A critical report on research. In: International Alfred Döblin Colloquium Leiden. Bern 1997, pp. 9-30.

- Sabina Becker: Alfred Döblin in the context of the New Objectivity I. In: Yearbook on culture and literature of the Weimar Republic. 1995, ISBN 3-86110-090-8 , pp. 202-229.

- Steffan Davies, Ernest Schonfield (eds.): Alfred Döblin. Paradigms of Modernism. Gruyter, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-021769-8 .

- Klaus Hofmann: Revolution and Redemption: Alfred Döblin's "November 1918". In: The Modern Language Review. 103, 2, (April 2008), pp. 471-489.

- Hans Joas: A Christian through war and revolution. Alfred Döblin's short story November 1918. In: Akademie der Künste (Ed.): Sense and Form. Volume 67, Issue 6, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-943297-26-3 , pp. 784-799.

- Erich Kleinschmidt: Döblin - Studies I. Depersonal Poetics. Dispositions of storytelling with Alfred Döblin. In: Yearbook of the German Schiller Society. 26, 1982, pp. 382-401.

- Gabriel Richter: Dr. med. Alfred Döblin - doctor, writer, patient and the State Psychiatric Hospital Emmendingen 1957. In: Volker Watzka (Hrsg.): Yearbook of the district of Emmendingen for culture and history 15/2001. Landkreis Emmendingen, 2000, ISBN 3-926556-16-1 , pp. 39-86.

- Klaus Müller-Salget: Alfred Döblin and Judaism. In: Hans Otto Horch (Ed.): Conditio Judaica. German-Jewish exile and emigration literature in the 20th century. Gruyter, Tübingen 1993, ISBN 3-484-65105-9 , pp. 153-164.

- Hans Dieter Schäfer: Return without arrival. Alfred Döblin in Germany 1945–1957 . Ulrich Keicher, Warmbronn 2007.

- Werner Stauffacher: Intertextuality and reception history with Alfred Döblin. "Goethe dawned on me very late". In: Journal of Semiotics. 24, 2002, pp. 213-229.

- Christine Maillard: Trinitarian speculations and historical theological questions in Alfred Döblin's religious talk The immortal man. In: International Alfred Döblin Colloquium Münster. Bern 2006, pp. 171–186.

Lexicon article

- Thomas Anz: Döblin, Alfred. In: Bruno Jahn (ed.): The German-language press. A biographical-bibliographical handbook. Volume 1, KG Saur, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-598-11710-8 , pp. 212-213.

- Thomas Anz: Döblin, Alfred. In: Wilhelm Kühlmann (Ed.): Killy Literature Lexicon. Authors and works from the German-speaking cultural area. 2nd Edition. Volume 3, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-020376-9 , pp. 58-62.

- Meike Pfeiffer: Döblin, Alfred. In: Christoph F. Lorenz (Ed.): Lexicon of Science Fiction Literature since 1900. With a look at Eastern Europe. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2016, ISBN 978-3-631-67236-5 , pp. 239–244.

- Uwe Schweikart: Döblin, Alfred. In: Bernd Lutz and Benedikt Jessing (eds.): Metzler Authors Lexicon. German-speaking poets and writers from the Middle Ages to the present. 3rd updated and expanded edition. Springer-Verlag, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 978-3-476-02013-0 , pp. 131-133.

- Manfred Vasold: Döblin, Alfred. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 317.

documentation

- Alfred Döblin: eagle and gunman . Director: Jürgen Miermeister, 2007. 45 minutes airtime.

Web links

- Literature by and about Alfred Döblin in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Alfred Döblin in the German Digital Library

- Alfred Doblin in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (English)

- Works by Alfred Döblin in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available for users from Germany )

- Works by and about Alfred Döblin at Open Library

- Lutz Walther, Kai-Britt Albrecht: Alfred Döblin. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Website of the International Alfred Döblin Society

- Döblin, Alfred: Letter and autobiographical sketch to Franz Brümmer, Hagenau, October 1917 in the digital edition "Nachlass Franz Brümmer "

- Alfred Döblin (1878–1957): “You gradually get to know each other thoroughly and want to move.” Biographical sketch by Gabriel Richter, Deutsches Ärzteblatt , June 22, 2007.

- Detailed biography at: lehrer.uni-karlsruhe.de.

- Alfred Döblin and WG Sebald

Individual evidence

- ^ Helmuth Kiesel: History of literary modernity. Language, Aesthetics, Poetry in the Twentieth Century. C. H. Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-51145-7 , p. 441 ( limited preview in the Google book search)

- ↑ Oliver Bernhardt: Alfred Döblin. In: dtv Portrait (Ed.) Martin Sulzer-Reichel. dtv, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-423-31086-4 , p. 11.

- ↑ Oliver Bernhardt: Alfred Döblin. In: dtv Portrait (Ed.) Martin Sulzer-Reichel. dtv, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-423-31086-4 , p. 12.

- ↑ Oliver Bernhardt: Alfred Döblin. In: dtv Portrait (Ed.) Martin Sulzer-Reichel. dtv, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-423-31086-4 , p. 15.

- ↑ Oliver Bernhardt: Alfred Döblin. In: dtv Portrait (Ed.) Martin Sulzer-Reichel. dtv, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-423-31086-4 , p. 18.

- ↑ Oliver Bernhardt: Alfred Döblin. In: dtv Portrait (Ed.) Martin Sulzer-Reichel. dtv, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-423-31086-4 , p. 18.

- ↑ Klaus Müller Salget: Alfred Döblin. In: Hartmut Steinecke (ed.): German poets of the 20th century. Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-503-03073-5 , p. 213.

- ↑ Klaus Müller Salget: Alfred Döblin. In: Hartmut Steinecke (ed.): German poets of the 20th century. Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-503-03073-5 , p. 215.

- ↑ Klaus Müller Salget: Alfred Döblin . In Hartmut Steinecke (ed.): German poets of the 20th century. Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-503-03073-5 , p. 217.

- ^ Peter Sprengel: History of German-Language Literature 1900–1918. From the turn of the century to the end of the First World War. In: History of German Literature from the Beginnings to the Present. Volume 12, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-52178-9 , p. 413.

- ↑ Hans Esselborn: The literary expressionism as a step towards modernity. In: Hans Joachim (Ed.): The literary modernity in Europe. Volume 1. Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1994, ISBN 3-531-12511-7 , p. 420.

- ^ Helmuth Kiesel: History of literary modernity. Language, Aesthetics, Poetry in the Twentieth Century. CH Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-51145-7 , p. 151.

- ↑ Sabina Becker: Between early expressionism, Berlin futurism, "Döblinism" and "new naturalism": Alfred Döblin and the expressionist movement. In: Walter Fähnders (Ed.): Expressionist prose. Bielefeld 2001, ISBN 3-89528-283-9 , pp. 21-44.

- ↑ Jochen Meyer, Ute Doster: Alfred Döblin. 1878-1988. An exhibition of the German Literature Archive in the Schiller National Museum in Marbach am Neckar . Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-928882-83-X , p. 109.

- ^ A b Helmuth Kiesel: History of literary modernity. Language, Aesthetics, Poetry in the Twentieth Century. C. H. Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-51145-7 , p. 437.

- ^ Gabriele Sander: Alfred Döblin . Reclam, 2001, ISBN 3-15-017632-8 , p. 27.

- ^ Liselotte Grevel: Traces of the First World War in Alfred Döblin's feuilletons of the 1920s. In: Ralf Georg Bogner (Ed.): International Alfred Döblin Colloquium Saarbrücken 2009. Under the spell of Verdun. Literature and journalism in the southwest of Germany on the First World War by Alfred Döblin and his contemporaries. Lang, Bern 2010, ISBN 978-3-0343-0341-5 , p. 159.

- ↑ Klaus Müller Salget: Alfred Döblin. In: Hartmut Steinecke (ed.): German poets of the 20th century. Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1994, p. 219 .; Alfred Döblin: "My address is: Saargemünd". Searching for traces in a border region. Gollenstein, Merzig 2010, ISBN 978-3-938823-55-2 .

- ↑ Ralph Schock (Ed.): '' Alfred Döblin. "My address is: Saargemünd". Searching for traces in a border region ''. "Tracks" row. Gollenstein, Merzig 2010, ISBN 978-3-938823-55-2 , pp. 226-230.

- ↑ Ralph Schock (Ed.): '' Alfred Döblin. "My address is: Saargemünd". Searching for traces in a border region ''. "Tracks" row. Gollenstein, Merzig 2010, ISBN 978-3-938823-55-2 , pp. 232-233.

- ↑ Ralph Schock (Ed.): '' Alfred Döblin. "My address is: Saargemünd". Searching for traces in a border region ''. "Tracks" row. Gollenstein, Merzig 2010, ISBN 978-3-938823-55-2 , p. 206.

- ↑ Erwin Kobel: Epilogue to the novel. In: Alfred Döblin: Wallenstein. DTV, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-423-13095-4 , p. 939.

- ^ Peter Sprengel: History of German-Language Literature 1900–1918. From the turn of the century to the end of the First World War. In: History of German Literature from the Beginnings to the Present. Volume 12, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-52178-9 , p. 153.

- ^ Hans Vilmar Geppert: The historical novel. History retold - from Walter Scott to the present for a historical modern novel. Francke, Tübingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-7720-8325-9 , p. 216.

- ^ Alfred Döblin: The German masked ball by Linke Poot. Knowledge and change. In: Walter Muschg in connection with the sons of the poet (ed.): Essays on literature. Selected works in individual volumes. Walter Verlag, Breisgau 1972, ISBN 3-530-16643-X , p. 100.

- ↑ The title is an allusion to Martin Luther's memorandum From the freedom of a Christian .

- ↑ Alfred Döblin: From the freedom of a poet. In: Erich Kleinschmidt (ed.): Writings on aesthetics, poetics and literature. Selected works in individual volumes. Walter Verlag, Olten 1989, ISBN 3-530-16697-9 , p. 130.

- ↑ Klaus Müller-Salget: Origin and Future. In: Hans Otto Horch (Ed.): Conditio Judaica. Judaism, anti-Semitism and German-language literature from World War I to 19337/1938 . Gruyter, Tübingen 1993, ISBN 3-484-10690-5 , p. 265.

- ↑ Klaus Müller-Salget: Alfred Döblin and Judaism. In: Hans Otto Horch (Ed.): Conditio Judaica. German-Jewish exile and emigration literature in the 20th century . Gruyter, Tübingen 1993, ISBN 3-484-65105-9 , p. 155.

- ↑ Cf. The Poetry Section of the Prussian Academy of the Arts. In: Viktor Žmegač, Kurt Bartsch (Hrsg.): History of German literature. From the 18th century to the present. Beltz Athenaeum, Weinheim 1994, ISBN 3-407-32119-8 , p. 175.

- ^ Alfred Döblin: Döblin about Döblin. The neurologist Döblin on the poet Döblin. In: Walter Muschg in connection with the sons of the poet (ed.): Essays on literature. Selected works in individual volumes. Volume 8, Walter Verlag, Breisgau 1963.

- ^ Helmuth Kiesel: History of literary modernity. Language, Aesthetics, Poetry in the Twentieth Century. C. H. Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-51145-7 , p. 354.

- ^ Alfred Döblin: Knowledge and change. Open letters to a young person. S. Fischer, 1931, p. 30.

- ↑ Klaus Müller Salget: Alfred Döblin. In: Hartmut Steinecke (ed.): German poets of the 20th century. Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-503-03073-5 , p. 213.

- ^ A b Helmuth Kiesel: History of literary modernity. Language, Aesthetics, Poetry in the Twentieth Century. C. H. Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-51145-7 , p. 438.

- ↑ Klaus Müller Salget: Alfred Döblin. In: Hartmut Steinecke (ed.): German poets of the 20th century. Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-503-03073-5 , p. 225.

- ↑ Dieter Schiller: The dream of Hitler's fall. Studies on German exile literature 1933–1945. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 978-3-631-58755-3 , p. 224.

- ↑ Helmut G. Asper: Something Better Than Death - Film Exile in Hollywood. Schüren Verlag, Marburg 2002, ISBN 3-89472-362-9 , pp. 430-433.

- ↑ Gottfried Benn: Doppelleben: two self-portrayals. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-608-93620-3 , p. 183.

- ↑ Karl-Josef Kuschel: Maybe God keeps some poets ...: Literary-theological portraits. Matthias Grünewald Verlag, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-7867-1574-2 , p. 24.

- ^ Anette Weinke: The Nuremberg Trials. Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-53604-2 , pp. 44-45.

- ^ Wulf Köpke: The Critical Reception of Alfred Döblin's Major Novels. Camden House, New York 2003, ISBN 1-57113-209-0 , p. 178.

- ^ Helmuth Kiesel: Literary mourning work: The exile and late work of Alfred Döblins. Gruyter, Tübingen 1986, ISBN 3-484-18089-7 , p. 1.

- ^ Helmuth Kiesel: Literary mourning work: The exile and late work of Alfred Döblins. Gruyter, Tübingen 1986, ISBN 3-484-18089-7 , pp. 1-2.

- ^ Alfred Döblin: Farewell and Return. In: Edgar Pässlar (Hrsg.): Autobiographical writings and last records. Walter Verlag, Breisgau 1980, ISBN 3-530-16672-3 , p. 431.

- ^ Wulf Köpke: The Critical Reception of Alfred Döblin's Major Novels. Camden House, New York 2003, ISBN 1-57113-209-0 , p. VII.

- ^ A b Wulf Köpke: Döblin's theater provocations. In: Yvonne Wolf (Ed.): International Alfred Döblin Colloquium. Mainz 2005: Alfred Döblin between institution and provocation. Bern 2007, ISBN 978-3-03911-148-0 , pp. 65-80.

- ^ Roland Dollinger, Wulf Koepke, Heidi Thomann Tewarson (eds.): A Companion to the Works of Alfred Döblin. Camden House, Rochester 2004, ISBN 1-57113-124-8 , pp. 8-9.

- ^ Robert Musil: Alfred Döblin's epic. In: Adolf Frisé (Hrsg.): Collected works 9. Critique . Rowohlt, 1981, ISBN 3-499-30009-5 , p. 1680. “I don't know what influence this book will have […] But even if I think about it coolly, I dare to say that this work is by should be the greatest influence! "

- ↑ Jochen Meyer: After seventy years. In: Jochen Meyer u. a. (Ed.): Alfred Döblin. In the book, at home, on the street. Presented by Alred Döblin and Oskar Loerke . Deutsche Schillergesellschaft, Marbach am Neckar 1998, ISBN 3-929146-90-8 , pp. 206-207.

- ↑ Thomas Keil: Alfred Döblins Our Dasein. Source philological studies . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2005, ISBN 3-8260-3233-0 , p. 8.

- ↑ Mirjana Stancic: Aestheticism - Futurism - Döblinism. Döblin's development from “Adonis” to “sailing trip”. In: Bettina Gruber, Gerhard Plump (Ed.): Romanticism and Aestheticism. Königshausen, Würzburg 1999, ISBN 3-8260-1448-0 , p. 263.

- ↑ Walter Muschg: Alfred Döblin: "The murder of a buttercup: Selected stories 1910–1950". Afterword, p. 422.

- ↑ Matthias Prangel: Alfred Doblin. Metzler, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-476-12105-4 , p. 26.

- ↑ Stephanie Catani: The birth of Döblinism from the spirit of the Fin de Siècle. In: Steffan Davies, Ernest Schonfield (Ed.): Publications of the Institute of Germanic Studies. Vol. 95. Alfred Döblin: Paradigms of Modernism. Gruyter, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-021769-8 , p. 33.

- ^ Walter Muschg: Alfred Döblin. The three leaps of the Wang-lun. Epilogue to the novel. Walter, Olten 1989, p. 481.

- ↑ Adalbert Wichert: Alfred Döblin's historical thinking. On the poetics of the modern historical novel. Germanistic treatises . Volume 48, Stuttgart 1978, p. 117.

- ↑ Steffan Davies: Writing History. Why Ferdinand the Other is called Wallenstein . In: Steffan Davies, Ernest Schonfield (Ed.): Publications of the Institute of Germanic Studies. Vol. 95. Alfred Döblin: Paradigms of Modernism. Gruyter, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-021769-8 , p. 127.

- ^ Sabine Schneider: Alfred Döblin: Berlin Alexanderplatz. The story of Franz Biberkopf. In: Sabine Schneider (Ed.): Readings for the 21st century. Classics and bestsellers of German literature from 1900 to today. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2005, ISBN 3-8260-3004-4 , p. 49.

- ^ Alan Bance, Klaus Hofmann: Transcendence and the Historical Novel: A Discussion of November 1918. In: Steffan Davies, Ernest Schonfield (Ed.): Alfred Döblin. Paradigms of Modernism. Gruyter, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-021769-8 , p. 296.

- ^ A b Klaus Müller Salget: Alfred Döblin. In: Hartmut Steinecke (ed.): German poets of the 20th century. Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-503-03073-5 , p. 216.

- ↑ Steffan Davies, Ernest Schonfield: Introduction. In: Steffan Davies, Ernest Schonfield (ed.): Alfred Döblin. Paradigms of Modernism. Gruyter, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-021769-8 , p. 1.

- ↑ Lars Koch: The war guilt question as existential memory work - Alfred Döblin's novel Hamlet or the long night comes to an end. In: Lars Koch, Marianne Vogel (eds.): Imaginary worlds in conflict: War and history in German-language literature since 1900. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8260-3210-3 , p. 186.

- ↑ Walter Delebar: Experiments with modern storytelling. Sketches of the general conditions of Alfred Döblin's novels up to 1933. In: Sabine Kyora, Stefan Neuhaus (Ed.): Realistic writing in the Weimar Republic. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2006, ISBN 3-8260-3390-6 , p. 137.

- ↑ Walter Delebar: Experiments with modern storytelling. Sketches of the general conditions of Alfred Döblin's novels up to 1933. In: Sabine Kyora, Stefan Neuhaus (Ed.): Realistic writing in the Weimar Republic. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2006, ISBN 3-8260-3390-6 , p. 136.

- ↑ Georg Braungart and Katharina Grätz classify the script as a music-theoretical work. Katharina Grätz: Conversations with Kalypso. In: Sabina Becker (Ed.): Döblin manual. Life - work - effect. Stuttgart 2016, p. 319 and Georg Braungart: Leibliche Sinn. The other discourse of modernity . Tübingen 1995, p. 285. Ernst Ribbat sees here a borrowing of music theory terms in order to realize the poetic claim. Ernst Ribbat: The truth of life in Alfred Döblin's early work . Münster 1970, p. 170.

- ^ Marion Brandt: The manuscripts for Alfred Döblin's journey in Poland , in: Yearbook of the German Schiller Society 2007, vol. 51, 2007, p. 51.

- ↑ Klaus Müller Salget: Alfred Döblin. In: Hartmut Steinecke (ed.): German poets of the 20th century. Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-503-03073-5 , p. 212.

- ^ Peter Sprengel : History of German Literature 1900–1918. From the turn of the century to the end of the First World War . Volume IX, CH Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-52178-9 , p. 413.

- ↑ Helmuth Kiesel: It was always modern. In: FAZ. June 25, 2007, accessed June 18, 2015 .

- ^ Christian Schärf: The novel in the 20th century. Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-10331-5 , p. 109.

- ^ Johann Holzner, Wolfgang Wiesmüller: Aesthetics of History . Innsbruck 1995, p. 90.

- ↑ Josef Quack: History novel and historical criticism. To Alfred Döblin's Wallenstein . Würzburg 2004, p. 381.

- ↑ Viktor Žmegač: The European novel. Gruyter, Tübingen 1991, ISBN 3-484-10674-3 , p. 336.

- ↑ Helmuth Kiesel: It was always modern. In: FAZ. June 25, 2007, accessed June 18, 2015 .

- ↑ Oliver Bernhardt: Alfred Döblin. Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-423-31086-4 , p. 167 ff.

- ^ Alfred Döblin: To Theodor Heuss. In: Walter Muschg (Ed.): Alfred Döblin. Letters. Walter, Olten 1970, p. 458.

- ↑ Gottfried Benn: Letter of November 21, 1946. In: Gottfried Benn: Briefe: Briefe an F. W. Oelze 1945-1949. Klett-Cotta, 2008, ISBN 978-3-608-21070-5 , p. 58.

- ↑ Oliver Bernhardt: Alfred Döblin. In: dtv Portrait (Ed.) Martin Sulzer-Reichel. dtv, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-423-31086-4 , p. 158.

- ↑ Horst Wiemer: Der Spätzünder, in: Der Spiegel, 23rd edition, from June 5, 1957. The journalist Horst Wiemer calls Walter Muschg's work The Destruction of German Literature , including a treatise on the exiled Expressionists, especially Alfred Döblin, is tangible . Unlike this, Döblin's role as an author could hardly have been compatible with the function of a literary figurehead.

- ↑ Oliver Bernhardt: Alfred Döblin and Thomas Mann. A checkered literary relationship. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2007, p. 192.

- ^ Bertolt Brecht: About Alfred Döblin. In: Werner Hecht, Jan Knopf, Werner Mittenzwei, Klaus-Detlef Müller (eds.): Works. Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt edition. Volume 23, Aufbau Verlag, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-351-01231-4 , p. 23.

- ^ Wilhelm von Sternburg: Lion Feuchtwanger. A German writer's life . Königstein 1984, pp. 178-179

- ↑ The literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki stated: The style-defining influence that Döblin exerted on the narrative style of German novelists after 1945 can only be compared with that of Kafka.

- ↑ Cf. I can only recommend looking for good and strict teachers. Dieter Stolz in conversation with Günter Grass. In: Alfred Döblin. Assassination of a Buttercup. A story and an interview with Günter Grass. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Wolfgang Koeppen: The miserable scribes. Essays. Marcel Reich-Ranicki (Ed.). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 3-518-03456-1 , p. 155.

- ^ Gabriele Sander: Alfred Döblin . Reclam, Stuttgart 2001, p. 93.

- ^ Dietrich Weber: German literature of the present. In individual representations . Kröner, Stuttgart 1976, p. 233.

- ^ Helmuth Kiesel: History of literary modernity. Language, Aesthetics, Poetry in the Twentieth Century. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-51145-7 , p. 441.

- ↑ Gunther Nickel: “Anyone who knows what longing is will understand me” - Uwe Tellkamp builds his Leipzig poetics lecture on sand. In: literaturkritik.de. April 9, 2009, accessed February 17, 2015 .

- ↑ Ignaz Wrobel : The right brother. In: The world stage. January 26, 1922, No. 4, p. 104.

- ↑ Thomas Mann: Misunderstood poets among us. In: Collected Works. Volume 10, S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1974, p. 883.

- ↑ Gottfried Benn: Letter to Johannes Weyl. (1946). In: Andreas Winkler, Wolfdietrich Elss (Hrsg.): Deutsche Exilliteratur 1933–1945. Primary texts and reception materials. 1982, p. 10.

- ^ Marcel Reich-Ranicki: Seven trailblazers. 20th century writer. dtv, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-423-13245-0 .

- ↑ Quoted from Walter Killy (Ed.): Literatur-Lexikon. Volume 3, 1989, p. 79.

- ↑ Life & Work - Chronicle on alfred-doeblin.de, accessed on June 27, 2016.

- ↑ Alfred-Döblin-Platz on xhain.info, accessed on June 27, 2016.

- ↑ Alfred Döblin in bronze has disappeared. In: Berliner Zeitung . July 2010.

- ↑ Information about the holdings of the DLA on Alfred Döblin.

- ^ Michael Fischer: The metamorphoses of a dazzling writer. In: iPad. On: tagesanzeiger.ch. December 13, 2011.

- ↑ Katrin Hillgruber: The factual fantasy. In: news, literature. On: badische-zeitung.de. December 24, 2011.