Epic theater

The term epic theater , coined by Bertolt Brecht in 1926, combines two literary genres , drama and epic , that is, theatrical and narrative forms of literature. In the 1920s, Bertolt Brecht and Erwin Piscator began to experiment with new forms of theater. They wanted to get away from the portrayal of tragic individual fates, from the classic stage of illusions and their pseudo-reality. Their aim was to portray the major social conflicts such as war, revolution, economy and social injustice. They wanted a theater that makes these conflicts transparent and moves the audience to change society for the better.

overview

The epic theater breaks with notions of quality, which devalued narrative elements on stage as inadequate implementation in lively play. Already in antiquity there were narrative elements in tragedy , for example through the choir , which commented on events, or through the wall exhibition and messenger report , in which characters described events that were difficult to portray on stage, such as major battles. However, these turned to the other stage characters, the appearance of reality was maintained.

Erwin Piscator and Bertolt Brecht deliberately used narrative elements differently: They broke through the reality of the stage. The avant-garde Piscator stage of the twenties used modern technology: simultaneous stages that presented several aspects of the action at the same time, treadmills, turntables and moving bridges. Piscator used image projections and, since 1925, documentaries that supplemented and superimposed the events on the stage. Brecht had z. B. Performers step in front of the curtain and comment on the events on stage. Actors turned to the audience, texts and pictures were faded in, there were musical interludes and songs. The identification of the audience with the hero was deliberately torpedoed.

The epic theater is in contrast to the Aristotelian theater, which pursued the goal of purifying the viewer by empathizing with what he saw, a process that Aristotle called catharsis . The epic theater wants to lead the audience to a distanced and critical view of the events on the stage. The goal is not compassion and emotions, but socially critical insights.

At the same time, other requirements of traditional drama are broken through, such as the classic structure of the drama with five acts , a given arc of tension, a turning point , a reduction in terms of locations and times of the event. The individual scenes stand for themselves, often there is an open ending, as in Brecht's The Good Man of Sezuan :

- "Dear audience, now don't worry:

- We know well that this is not the right conclusion.

- We had in mind: the golden legend.

- She came to a bitter end in secret.

- We stand disappointed ourselves and look affected

- Close the curtain and open all questions. "

Today, the term “epic theater” is mostly used exclusively to refer to the works and staging techniques of Brecht and - with some reservations - Piscators, although there were numerous dramatists in the 20th century who used epic elements. Also, as Jürgen Hillesheim makes plausible, many of the most significant elements of Brecht's epic theater were developed in Brecht's work even before his encounter with Marxism. Günther Mahal sees the exclusive claim as a tactical discourse success of Brecht. Brecht had succeeded in capturing and disavowing a large part of the drama in front of him under the umbrella term "Aristotelian theater". Mahal considers this to be a “caricature” and “manipulative”.

Brecht has continuously developed the concept of epic theater and adapted it to the needs of his staging practice. Although he summarizes his concept at a few points, the range of Brecht's new drama is only revealed in a large number of scattered documents, partly in model books on pieces, in notes and typescripts, in letters and journals. The epic theater is therefore to be understood as an open concept. Nevertheless, some cornerstones can be recorded that arise from Brecht's didactic objectives. The break with the theater of illusions should enable the audience to judge complicated social processes soberly. For this purpose, the individual elements of the drama are examined for possibilities of bringing the complex contradictions of the modern world onto the stage. Music, lighting, actors, stage design and texts should show something to the audience and be used separately and in contrast. Distance should be established again and again, tension, compassion and illusion should be broken.

The epic theater of Brechts and Piscators is politically active. The tight corset of traditional drama is broken because both wanted to depict complex political relationships. The epic theater is Marxist- oriented, wants to work against exploitation and war, to work for a socialist change in society.

In addition to the term “epic theater”, Bertolt Brecht later used the term “dialectical theater” more often for his overall concept.

Origin of the term "epic theater"

Both Brecht and Piscator have claimed to have coined the term “epic theater”. Brecht employee Elisabeth Hauptmann states that Brecht developed the idea in 1926 in the context of the play Jae Fleischhacker . Brecht said “that our world today no longer fits into drama” and began to develop his counter-concept of epic theater. "The actual theory of the non-Aristotelian theater and the expansion of the V-effect can be ascribed to the Augsburgers ", writes Brecht about himself in the brass sale . Piscator's merit is "above all the turn of theater to politics". In the end, Brecht speaks diplomatically of simultaneous use, "the Piscator more in the stage (in the use of inscriptions, choirs, films, etc.), the Augsburg in the acting style."

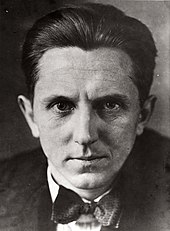

Piscator stated that his staging of the play Fahnen by Alfons Paquet in May 1924 at the Berlin Volksbühne was the first break with the "scheme of the dramatic plot". Piscator had introduced the actors of the Paquet play about the Haymarket Riot to the audience through the extensive use of image projections. In addition, between the scenes he projected subtitles onto two screens at the edge of the stage. When Brecht successfully adapted this and other stylistic devices from Piscator's theater in the following years, Piscator proclaimed the conceptual and methodical authorship of the epic theater in his book Das Politische Theater 1929 for himself. He erroneously stated that Paquet's play had already been subtitled “epic drama” (in fact, the subtitle was “a dramatic novel”). However, Alfred Döblin had already used the term epic in connection with Piscator's theater work in 1924. In the context of the flag production in the Leipziger Tageblatt of June 11, 1924, Döblin stated that the playwright Paquet was not lyrical but “epically inflamed”.

Regardless of the disagreement about the authorship of the individual elements of the epic theater, the importance of Piscator for the new form of drama is beyond doubt. Sarah Bryant-Bertail describes Brechts and Piscator's joint dramatization of the novel Der brave Soldat Schwejk by Jaroslav Hašek in 1928 as the “prototype of epic theater”. For his “revolutionary” and “proletarian” productions in the service of the class struggle, Piscator developed ideas and technical means that Brecht later used, albeit often modified. Piscator activated the audience and experimented with modern stage technology: film and image projections, simultaneous stages and various machines opened up new possibilities. Piscator, with his love of experimentation, is - as Brecht puts it boldly - "the great master builder of epic theater ". Nevertheless, Jan Knopf states that Brecht viewed Piscator's impressive stages critically, as innovative, but only used them formally. Out of political sympathy, however, he only rarely expressed this criticism. Piscator's theater projects were often criticized by contemporary critics as being too propagandistic . Hinck sees Piscator's theater as “reportage-like and tendentiously tailored reality.” There was also a fundamental difference between Brecht's and Piscator's productions: Piscator wanted to sweep the audience away, in stark contrast to Brecht's concept of sober, detached play.

Sarah Bryant-Bertail attributes the fact that the term “epic theater” was almost exclusively associated with Brecht's dramas to the tremendous effect of the production of Mother Courage and the extensive documentation of the performance.

Thomas Hardy , who subtitled his mammoth work The Dynasts in 1904, “ An epic-drama of the war with Napoleon, in three parts, nineteen acts and one hundred and thirty scenes” , was the forerunner of the conceptual connection between the genres . However, the similarity of the name does not indicate a similar concept, but was chosen "only because of the length and the historical subject".

Epic and Drama in the History of Literature - Precursors

Lange was the poetics of Aristotle influential to the understanding of the drama, even if his principles were modified again and again throughout history. The separation of the literary genres regularly became a measure of quality: epic and drama should never be mixed up. Marianne Kesting points out that there were always other dramatic forms that were mostly ignored. She mentions the medieval mystery play , the Corpus Christi games of Calderón and the drama of Sturm und Drang as epic forms . Brecht himself mentions other role models:

“From a stylistic point of view, epic theater is nothing particularly new. With its exhibition character and its emphasis on the artistic, it is related to the ancient Asian theater. The medieval mystery play as well as the classical Spanish and Jesuit theater showed educational tendencies . "

What fascinates Brecht about the Asian theater is the “great importance of the gesture”, the “depersonalized mode of representation” and the minimum of illusion, including the sparing decoration and interruptions in the game.

Brecht also often refers to William Shakespeare , whose dramas he found "extremely lively", eager to experiment and innovative. For Brecht, Shakespeare was "a great realist"; his dramas showed "those valuable break points where the new of his time met the old."

Marianne Kesting demonstrates early doubts about the strict separation of drama and narrative texts in Europe in the correspondence between Friedrich Schiller and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe . With all their admiration for Aristotle, the two authors had nevertheless questioned whether each subject could be reconciled with the strict separation of genres. In Schiller's case, the complex story of Joan of Arc , in Goethe's work on Faust, led to skepticism about a dogmatic separation of genres. The actual forerunners of the epic theater emerged after Kesting in Vormärz , in the dramas Christian Dietrich Grabbes and Georg Büchner . She sees Büchner's “models of epic dramaturgy” in the plays. The drama fragment Woyzeck already shows the anti-heroes, “determined by the social milieu”, at the mercy, passive, “victims” of a “broken society”. “But the heroism of suffering and the determination of action cause the active moment in the drama to decline.” Brecht also expressly mentions the importance of Woyzeck for his early literary development.

Walter Hinck sees the influence of the Commedia dell'arte in some of the typified, parodistically drawn characters of Brecht . The figure of Shu Fu from the Good Man of Sezuan would correspond to the figure of Pantalone . Pantalone belonged in the Italian folk comedy to the "Vecchi", the representatives of the upper class. When Brecht uses masks, as in those of the Commedia dell'arte, they are not tied to a specific emotional expression, they serve, like the grotesque exaggeration of the game, the satirical representation of the upper class. With regard to the puntila , Brecht expressly demanded orientation towards the Commedia dell'arte. It wasn't just about types and masks, but also about artistic movement direction.

Influence of naturalism

Against the changed social background in the age of industrialization , the Aristotelian model was increasingly questioned in the 19th century. Naturalism developed new concepts . The starting point for naturalistic playwrights such as Gerhart Hauptmann and Henrik Ibsen were the novels by Émile Zola and Fjodor Michailowitsch Dostojewski . In literary studies, Zola is often seen as the most important predecessor of Brecht because of his theoretical writings, although Brecht later very clearly distinguished himself from naturalism.

In one respect, Zola's naturalistic drama was contrary to Brecht's epic theater: the French wanted the perfect illusion. Actors and sets should give the impression of real life on stage. But Zola nevertheless clearly transcended the Aristotelian model. Everyday life should be shown, character representation was more important to him than the fable. There should be individual independent scenes, designed like excerpts from a novel, which should be scientifically and experimentally directed . Zola sees Moliere's Der misanthropist as an early example of narrative drama. As early as 1881, Zola wrote in a criticism of the French drama of his time: "The boards of the carnival entertainers are wider and more epic (plus large et plus épiques) than our miserable stages on which life is suffocating." Zola tries to show with examples that that Theater changed depending on history. The classic drama has become obsolete and new things have to be tried out. Essential elements of such experiments can be found in the old epic drama and the naturalistic novel. The German naturalists took up Zola's ideas. Above all, they adapted the thesis of the formative influence of the novel on the drama.

Although Brecht sharply distanced himself from the naturalists on several occasions, one can record some parallels: the interest in experiments, in the scientific approach, the rejection of religion and metaphysics , dramas with an open ending, the epization of drama, ties to old forms of drama and the fair , Belief in the influence of historical change on the theater. The decisive differences are the naturalistic idea of the perfect illusion and the naturalness of the descriptions, which did not seem to allow any change. Unlike the naturalists, Brecht, like Aristotle, considered the fable to be decisive; it should show the social contradictions, the social structures.

Zola already speaks of epic forms of representation. According to Reinhold Grimm, one difference to Brecht lies in the concept of the epic itself. If Zola saw the narrator as a neutral recorder who does not interfere in the novel, then for Brecht the authorial narrator was the model for his drama. Grimm proves this in Brecht's drama The Caucasian Chalk Circle , in which the narrator, who takes part in the stage events all the time, comments, introduces characters and knows their thoughts and embeds the stage events in the framework of an old story. Jan Knopf emphasizes the contrast in content. According to Brecht, naturalistic literature merely shows the facade of social reality, which appears to be unchangeable. Even the exact image of a factory does not show its internal structure. Brecht, on the other hand, does not simply want to depict social reality, but rather to show structures and opportunities for change.

Influence of opera

Dealing with the opera was a central theme for Brecht. Between 1926 and 1956, Brecht worked on around two dozen opera projects. Various authors point out the importance of music for the development of the Brechtian theater concept. In a lecture in 1933, Thomas Mann referred to the epic character of Richard Wagner's operas and compared Wagner with Honoré de Balzac , Lev Nikolajewitsch Tolstoy and Émile Zola . He interprets Wagner's Ring des Nibelungen as a multi-part drama and “scenic epic”. “Wagner's main work” owes “its greatness of its kind to the epic artistic spirit”.

Brecht nevertheless saw Richard Wagner as his main adversary, but perhaps precisely because of this he developed his position as an alternative and thus under Wagner's influence. Nevertheless: In the lives of Brecht and Wagner, a number of parallels catch the eye. Both became successful through their operas at the age of 30, both were interested in Shakespeare's Measure for Measure and Sophocles ' Antigone and both later fought for their own home. Even Theodor W. Adorno saw the epic theater in the design of the ring basics. Joy Haslam Calico interprets Brecht's incredibly productive phase at the end of the 1920s as a dual strategy, as an attempt to reform opera from the inside through her own operas and at the same time to create an alternative in the form of the didactic pieces. Despite Brecht's fundamental criticism of the bourgeois opera industry with its passive audience and its representative function, there is also a source of epic elements on the stage in the opera world. In addition to Wagner's work, particular reference should be made to the Da Ponte operas by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. A number of authors are not looking for the influence of Wagner's opera on modern theater in parallels, but in the deliberate dissociation of the authors from Wagner: “To put it bluntly, modernist theater, of which epic theater has long been the standard-bearer, may be the illegitimate child of opera. "

Ferruccio Busoni's proposals for reforming the opera are even considered by some authors to be a blueprint for epic theater (“blueprint for epic theater in general”). Busoni, Kurt Weill's teacher , criticized the classic concept of repetition of the stage processes through music and called for the examination of when music should and when not. Busoni asked the composers to have the courage to break with the existing and to activate the audience, and showed that “in order to receive a work of art, half the work on it must be done by the recipient himself”. Like Brecht later, he turned against the theater of illusions:

"Just as the artist, where he is supposed to stir, must not be stirred himself - if he should not lose control over his means at the given moment - the viewer, too, if he wants to taste the theatrical effect, must never see it for reality, should not the artistic enjoyment decline to human participation. The actor "plays" - he does not experience. The viewer remains incredulous and therefore unhindered in spiritual reception and gourmet taste. "

Busoni's stage works, the practical implementation of his ideas, such as the two one-act plays from 1917, Turandot and Arlecchino , also had a strong influence on Kurt Weill . Typical features were free tonality, short, self-contained pieces. Small, parodistic musical quotations were a pre-form of the V-effect .

Contemporary influences on Brecht's drama

Brecht's theater experiments are related to a cultural upheaval. The theater scholar Hans-Thies Lehmann states a "theater revolution at the beginning of the 20th century" and names two elements that the very different experiments have in common: the " autonomy of the staging in relation to the literary works" and the " involvement of the audience in the events on the stage" . The historical background was the loss of importance of the individual in the rapidly growing cities, the mass experiences in war and revolution.

"Against this background, the drama overtakes a fundamental crisis, because its characteristics, such as individual conflict, dialogue and self-contained form, can no longer reflect the new experiences."

The avant-garde theater also reacts to the escalation of political conflicts and takes a stand. They experimented with forms such as Brecht's “teaching theater”, the political revue, agitprop , aggressive attacks on the audience, provocations. The representative theater evening turned into a disturbing event, in very different ways people rebelled against traditions and institutions, staged scandals, actions, mass events. Dada , futurists and other currents create forerunners of happenings and performance. Walter Hinck points out that even before Brecht and Piscator Wsewolod Emiljewitsch Meyerhold undertook theater experiments in Moscow after the October Revolution , as can later be found in Brecht. He removed the curtain, projected films and had moving stages built with machinery. Meyerhold understands his radical reforms as a recourse to the total work of art of ancient tragedy:

“When the theater demands the abolition of the decoration that stands in line with the actor, when it rejects the ramp, subordinates the actor's play to the rhythm of diction and plastic movement, when it demands the rebirth of dance and the audience attracts active participation in the plot - does not such a conditional theater lead to the rebirth of antiquity? Yes. The architecture of the ancient theater is precisely the theater that has everything that today's audience needs. "

The concept of alienation also finds its forerunner in the Russian avant-garde. The Russian formalists assumed that the poetic language, frozen by habit, could only be brought back to life through irritation and alienation. With the means of art they wanted to break through the "automation" of perception. In 1916, Šklovskij coined the term "ostranenie" (остранение) or alienation. Art should develop processes to make reality perceptible again by irritating and destroying the familiar.

For the period around the Second World War, Klaus Ziegler also observes the departure of various authors from the “form type of modern art drama” and a recourse to much older, narrative concepts. Ulrich Weisstein emphasizes the influence of Lion Feuchtwanger on this new mixture of epic and drama. Feuchtwanger's “dramatic novel Thomas Wendt ” (1918–1919) does not just represent an individual fate, but a “worldview”, as Brecht later also sought. In Feuchtwanger's work, the novel elements should overcome the narrowness of the drama, the drama should increase the tempo and convey feelings. The effect of Feuchtwanger's formal experiment was great. So took Alfons Paquet the concept of dramatic novel 'for his drama Flags (1923) and chose the same subtitle. Feuchtwanger himself stated that the 20-year-old Brecht visited him while he was working on the “Dramatic Novel”: “This term gave Brecht food for thought. He felt that one had to go much further in merging the dramatic with the epic. He kept making new attempts to create the “epic theater”. ”Together, Feuchtwanger and Brecht worked on the 1923 drama Leben Eduard des Zwei von England by Christopher Marlowe for the Münchner Kammerspiele and developed basic epic structures (e.g. dissolving the structure and the verse form , Scene title, stage directions aimed at disillusionment).

In buying brass, Brecht himself names two other contemporaries who would have significantly influenced his development. He saw Frank Wedekind , whose style was characterized by cabaret and bank singing and who performed his own song compositions for the guitar. Sarah Bryant-Bertail sees Wedekind as an idol of the young Brecht, who, like other authors of his generation, was radicalized by the October Revolution, World War and the Weimar catastrophes. "But he learned most from the clown Valentin, " writes Brecht about himself in the third person. Hans-Thies Lehmann shows that not only Brecht was influenced by cabaret: some of the elements of the avant-garde movement came from forms of cabaret and tinkering. The independence of content elements ties in with the “number principle” of “cabaret, revue, fair and circus”, the “culture of songs, political bench songs and chanson” also inspired Piscator, Wedekind, Max Reinhardt and others. Brecht systematically develops these building blocks for his epic theater, is less of an agitator than a piscator, relies on judgment, "the viewer's understanding (ratio)" and does not provide any solutions.

Brecht's epic theater

Theater and society

According to Brecht, epic theater is supposed to set social and political changes in motion. The demonstration of social contradictions on the stage is intended to activate the audience, to convey criticism of belief in fate and a materialistic attitude . The theater is to be transformed from an instrument of representation and entertainment for the upper class into a critical event, especially for the proletariat .

“According to Hinck, Brecht's theoretical foundations of his 'epic theater' are based on an aesthetics (poetics) of the strictest sense. The choice of all the dramatic and theatrical means, how the design is done, is decided by the goal. "

As a Marxist , he understood his dramas as "an instrument of enlightenment in the sense of a revolutionary social practice". In order to enlighten, a thought process must be triggered in the viewer. For this he should become aware of the illusion of the theater and should not, as required in the classical theater theory of Aristotelian catharsis , be captured by the action, feel pity for the protagonist, perceive what has happened as an individual fate and accept it as such. Rather, he should see what is presented as a parable of general social conditions and ask himself how something in the depicted grievances could be changed. Brecht's theory of drama is a political theory; he sees his plays written in exile as attempts for a new kind of theater, the “theater of a scientific age”. This theater was supposed to expose the ideology of the rulers and uncover their hidden interests.

Brecht's play Mother Courage and Her Children exposes the ideology of the mighty and the churches, the Thirty Years War is about religion, one fights godly in a "religious war". This ideology is exposed in various ways: by parody or satirical the lofty words are called into question, the Protestant field preacher appears as a powerless, hypocritical figure who has absolutely nothing to say to the military.

Brecht wanted an analytical theater that encourages the viewer to reflect and question at a distance. To this end, he deliberately alienated and disillusioned the game in order to make it recognizable as a drama in relation to real life. Actors should analyze and synthesize, i.e. H. Approaching a role from the outside and then consciously acting as the character would have done. Brecht's epic theater is in contrast to both Stanislawski's teachings and the methodical acting skills of Stanislawski's pupil Lee Strasberg , which sought to be as realistic as possible and required the actor to put himself in the role.

Some literary scholars differentiate between Brecht's epic theater concept and the didactic pieces that emerged at the end of the Weimar period and are intended to motivate laypeople to play and break completely with classical theater concepts and institutions. Hans-Thies Lehmann, for example, appears "the epic theater rather than the last large-scale attempt to preserve literary theater". In contrast to the wild theater experiments of the time, which gave up classical literary theater entirely, such as Antonin Artaud's Theater of Cruelty , Brecht adhered to Aristotelian tenets such as the central importance of fable .

“The political didactic in his plays and the predominance of the linguistic separate him from the proponents of anti-literary theater; the comparison with Mejerchol'd and Artaud, with futurists , constructivists or surrealists makes his theater appear strangely classic. ... In a European environment, where wildly experimenting with the limits of theater, attempting transitions to installation , to kinetic sculpture or to political manifestation and festivities, Brecht relies on the sobering of the stage, which knows no mood light, the 'literarization 'of the theater and the serenity of the audience. He calls it the 'smoke theater'. "

Comparison: dramatic theater - epic theater with Brecht

Brecht's criticism of the classical tragedy first affects the basic structure of the fable. In the Small Organon for the Theater (1948), Brecht explains that the conflict between the tragic hero and the divinely legitimized norms of society always ends tragically for the individual. Against this background, a change in society seems impossible, history as blind fate. Contrary to this basic construction, Brecht wants to show social conditions as changeable, to expose them as the work of people. For Brecht, the first means of showing the real interests behind the firmly established norms of capitalist society is to “deprive social processes of the stamp of the familiar”.

From 1933 Brecht systematically worked out his concept of the epic theater and developed it further in texts and productions. Brecht did not understand epic theater as an absolute contrast to dramatic theater; there were “only accent shifts”. Epic theater should be narrative, arouse the audience's activity, lead them to decisions and contrast them with what is shown. Imitation ( mimesis ) and identification should be avoided in epic theater. Brecht demanded constant reflection from the actor . The performer should not “empathize” with the role as in traditional theater practice, but “show” it and its actions and evaluate them at the same time. An essential method is the alienation effect , which modifies an action through interrupting comments or songs in such a way that the viewer can build a distance to the piece and its performers. The set design and equipment can also increase this distance.

This distant aesthetic, which is aimed at reason and judgment, also has political backgrounds for Brecht. At the end of the Weimar Republic , Brecht sees a “crisis of emotions”, a “rationalistic twist” in the drama. According to Brecht, “fascism with its grotesque emphasis on the emotional” and “a threatening decline” of reason also “in the aesthetics of Marxism” led to an emphasis on reason.

The literary scholar Walter Hinck conceptually sums up the contrast between epic theater and the “modern art drama” shaped by Lessing and the Weimar Classics as the contrast between “open” and “closed” dramaturgy. The “ ideal type ” of the classical, closed drama, in “analogy to the organism […], gives the appearance of natural growth”. Each event follows logically from the previous one, the chronological sequence is thereby determined. The poet and director are no longer visible during the performance, the actors are completely absorbed in their roles. The world on stage appears as a reality, the opening to the audience is seen as the “fourth wall”. According to its structure, the “stage of illusion” is “without reference to everyday reality and the audience”.

The open form, on the other hand, renounces the appearance of reality, it shows more than the invented world of the stage. "The drama reveals the conditions of its existence". The poet, director and audience can be included in the action on the stage; the scenes develop in loose succession, not in a strict chain of cause and consequence. The “stage open to the audience” offers opportunities to show the world of drama “as a fictional, as a world of appearances” and to exceed its limits. This gives the stage world didactic possibilities; it can be viewed as a parable or thought experiment.

The following scheme with some “shifts in weight from dramatic to epic theater” is reproduced in the version revised by Brecht in 1938 from the notes on the opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny :

| Aristotelian form of the theater | Epic form of theater |

|---|---|

| acting | narrating |

| involves the viewer in a stage action | turns the viewer into the viewer |

| consumes its activity | awakens its activity |

| enables him to feel | forces decisions from him |

| experience | worldview |

| The viewer is put into something | he is set opposite |

| suggestion | argument |

| The sensations are preserved | driven to knowledge |

| The viewer is right in the middle | The viewer stands opposite |

| witnessed | educated |

| Man is assumed to be known | The human being is the subject of the investigation |

| The immutable man | The changeable and changing person |

| Voltage on the output | Tension on the corridor |

| One scene for the other | Each scene for itself |

| growth | Assembly |

| Events linearly | in curves |

| evolutionary inevitability | Jumps |

| The human being as a fix | Man as a process |

| Thought determines being | The social being determines the thinking |

| feeling | Ratio (understanding, reason) |

| idealism | materialism |

Individual aspects of Brecht's epic theater

The building blocks of epic theater, which are presented below, are to be understood as a repertoire that Brecht uses, varies and further develops in ever new ways.

Narrator on the stage

Brecht's play The Caucasian Chalk Circle is the audience of one authorial presented narrator who comments on the action on stage, presenting figures and knows their thoughts and by a background story creates distance. The narrator influences the interpretation of the event and creates a second level of action according to Knopf.

"The design of the 'authorial narrator' on the stage ... is the most extensive epic means, as it suspends the dramatic plot as an 'illustrated narrative' as in the case of the morality singer, whereby the separation of narrator and narrative object is emphasized (different language, different attitude, Narrator as singer). The narrator can cancel the temporal continuity [...]: he has control of the course of the plot and can (as in the film) rearrange it, 'cut' it. With regard to the audience, the narrator can confront the action directly (with a request to take note of it in a certain way). "

Walter Hinck shows that the narrator creates tensions and breaks in the dramaturgy. In contrast to the novel, the narrator is clearly distinguished from his narrative subject, the scenic play. Brecht marked this distance both linguistically and through the arrangement on the stage. In his production of the Caucasian Chalk Circle, Brecht placed musicians and singers in a box between audience and stage, for Hinck "the 'ideal' place [...] at the intersection of stage and auditorium".

More typical of Brecht's use of a narrator on stage is the temporary stepping out of his role by one of the actors. The actor turns to the audience and comments on the events or sings a song in front of the curtain. With such breaks, Brecht creates distance from the action, summarizes the plot or declares it to be mere play. In the Good People of Sezuan, for example, the actress Yang in the 8th picture slips into the role of the narrator.

"Ms. Yang (to the audience): I have to tell you how my son Sun was transformed from a depraved person into a useful person through the wisdom and severity of the generally respected Mr. Shui Ta [...]."

The scenic play now shows this development and fades back 3 months. As a result, “there are two dimensions of time on the stage, according to Hinck: that of the scenic and that of the reporter. The stage is given the character of a simultaneous stage due to the temporal structure . ”But the stage is also spatially divided into the space of the scenic play and the location of the commenting Ms. Yang, which does not belong to the event. According to Walter Hinck, in this juxtaposition of epic commentaries and the representation of the actors, the role of the narrator appears “as the really authentic, objective of the two poles”. The game appears as a demonstration of past events that the narrator has known for a long time. Because the narrator directs the game and can 'call up' various events from the past one after the other, the strict temporal order of the drama is abolished, the scenes become interchangeable.

In Brecht, the public addresses are tied to the plot to different degrees. You can move the action forward, pause, or disengage from the action entirely and relate to the reality of the audience. The speakers regularly address social and economic problems.

Actors' role distance

Brecht's idea of the distant game has a prominent forerunner in Denis Diderot . In his writing Paradoxon about the actor Manfred Wekwerth , the enlightener called for a reflected development of the role and the renunciation of empathy.

“Following the concerns of the Enlightenment, Diderot was not enough to simply imitate nature and its perceptions in the theater to move from - as he writes - 'feeling to thinking people'. For Diderot, it is not the actor's own suffering on stage that leads to great emotions, but to what extent he is able to imitate the great emotions that he has observed in people with a 'cool head and excellent judgment'. And the less he shares them on stage, the more effective they become. Yes, Diderot recommends, in order to keep 'a cool head and excellent judgment', even developing the opposite feelings: in a love scene also those of aversion, in a pathetic scene their prosaic opposite. "

The central point of the Brechtian idea of the actor is the abandonment of complete identification with the role. In this respect, the Russian director Stanislawski with his naturalistic concept of the perfect illusion that the actor should create is the counter-figure to Brecht's concept of distant play. Stanislawski perfected the technique of perfect imitation, the actor should show real life on stage through empathy down to the last detail. He wanted to enable the viewer to fully empathize. Brecht thinks this concept is completely unsuitable for showing and understanding the complex reality of modern society. In order to create a critical distance to the characters on the stage, Brecht "alienated" their representation through distanced play or irritating details.

Käthe Rülicke-Weiler shows that the "alienation" of the characters can begin with the casting of the role. Brecht let young actors play old people, for example the young Angelika Hurwicz in Frau Carrar's rifles and old Frau Perez. Brecht took advantage of other possibilities of irritation in the cast, in which, in the fear and misery of the Third Reich , he cast the SA man with a particularly personable actor. “The meanness of the plot was not explained by the 'character', but by the fascist ideology.” In the 1948 performance of Brecht's Antigone in Switzerland, 47-year-old Helene Weigel played the girl Antigone, both her fiancé Haimon and the King Creon were cast with significantly younger actors.

Directing techniques

In order to promote the role distance, a "hypothermia of the game", in the actors, Brecht developed directing techniques that make the actors aware that they should show the stage figure from an inner distance and not identify completely with it. The actor "only shows his role". Brecht describes a simple means in relation to the rehearsals for Mother Courage :

“Only in the eleventh scene do I turn on epic tasting for ten minutes. Gerda Müller and Dunskus, as farmers, decide that they can do nothing against the Catholics. I have them add 'said the man', 'said the woman'. Suddenly the scene became clear and the Müller discovered a realistic attitude. "

Other means of creating role distance are “transferring to the third person”, relocating the currently depicted events to the past, or giving instructions to the stage. Another exercise suggested by Brecht for distanced play is the transfer of classical material into a different milieu. The third act of Schiller's Maria Stuart is supposed to become the "argument of the fish women". A role reversal between the actors at rehearsals, for example between master and servant, is a means of conveying the meaning of the character's social position. "The actor not only and not so much has to embody his character, but also and above all her relationship to other characters."

“Brecht's actor should not completely 'transform' himself into the character portrayed, 'be' it; Rather, it should make it clear to the viewer that he is 'quoting' a text that he had to learn by heart, just as he - in a figurative sense - also quotes the figure, that is, its behavior and actions, by referring to its body , shows its expression etc. accordingly. "

Brecht explains his idea of role distance using a street scene: “The eyewitness to a traffic accident demonstrates to a crowd how the accident happened”. The point here is to show a fact that the illusion of reality is not required, the game has the "character of repetition". Analogous to this, let the director play an expected attitude at rehearsal or show a role when an actor is demonstrating something to another.

In the preludes to the Caucasian Chalk Circle and the Parable The Round Heads and the Pointed Heads , as in secular games of the Middle Ages, the performers first take to the stage and only then take on their roles in order to illustrate the playful nature of the performance.

The "gesture" as an expression of a social position

For the role distance of the actors, the showing of a figure without being completely absorbed, the "gesture" (Brecht also speaks of the "gesture") is of central importance. As a director, Brecht worked intensively on the physical expression of mental and social attitudes. His concept is similar to the habitus term in modern sociology : the internalized behavior of a person, their gestures, language, clothing, taste, the way they act and think, all indicate their rank and status in society. Brecht's definition of the "gesture" emphasizes the social function:

"A gesture is understood to be a complex of gestures, facial expressions and (usually) statements that one or more people direct to one or more people."

During rehearsals, Brecht paid close attention to details, discipline and restrained play: Helene Weigel as a grieving mother in the courage stands in front of her shot daughter Kattrin and sings her a lullaby as if she were just sleeping. Finally she hands the peasants around to pay for the funeral, hesitates a moment, and then puts a coin back in her wallet. The simple gesture shows the audience the character of courage: even in the face of the death of her child, she remains a businesswoman and does not change. This "quiet game" of the Weigel, their reserved, "Asian body language" generated a "hyper-precise social expression", but at the same time something universal that was captured on tours even in countries where the audience did not understand German. In other pieces, too, Brecht and the actors develop simple, repeatedly shown gestures that characterize people and their social behavior, such as the outstretched hand of the corrupt judge Azdak in the Caucasian Chalk Circle .

However, these simple and clear gestures must not obscure Brecht's “emphasis on artistic, dance and occasionally mask-like”.

Brecht generalized the term gesture from body language to other areas of representation. Music, language and text are “gestural” when they specifically show social relationships between people.

Typing of the figures

Walter Hinck shows how Brecht's protagonists make their compromises, the good soldier Schwejk as well as Shen Te in The Good Man of Sezuan or Galileo Galilei . Brecht deliberately avoids the tragic. Walter Benjamin speaks of Brecht's untragic hero. Sarah Bryant-Bertail describes the basic construct of turning away from the tragic:

"The epic theater demystifies the concept that it is essential for human nature to live through an inescapable destiny by showing that both human nature and destiny are historical and thus changeable constructs."

Brecht reduced his figures because for him man is the intersection of social forces, not a strong individual in whose behavior his character is expressed. Brecht does not present his characters as individuals with a decision, but rather in social contexts whenever possible. He is more concerned with social processes than with the psyche of his characters. In doing so, he gives the characters their lives, they usually get by through cunning and compromises. On the stage they usually do not make any changes, the mother Courage learns nothing. However, the pieces are designed in such a way that the audience should understand what alternatives there are, what mistakes the characters make on stage.

The characters of Brecht therefore require the actor to portray their “model character”, to convey what is exemplary. From a distance he can take sides for or against his character and demonstrate this partisanship to the audience so that it can form a judgment. So the actor takes on a "mediator" between the game on stage and the audience.

Scope for actors

Despite the typification of the characters, Brecht wants to put multi-layered “people” on the stage, “who make possible premonitions, expectations, and sympathies that we show people in reality”. Using the example of the samples for the Caucasian chalk circle , John Fuegi shows how Brecht systematically worked out the contradictions of his figures. If the selflessness of the maid Grusha was worked out in a rehearsal, a negative aspect of her personality was the focus of interest in the continuation, always with the aim of “creating a multi-layered person”. According to Brecht, the way to achieve this is “the conscious application of contradiction.” Brecht only considers figures that can surprise to be suitable for enabling the audience to think critically.

The complexity of the characters also means that the actor should show them in such a way that they could act differently despite all constraints. Brecht still considered it acceptable for the actors to fall out of the role and show their feelings for the character. Anger of the actress about the behavior of courage or sadness about the peasant woman who renounced her son, who had long since fallen, served to "tear the illusion apart", improvisations and extremes of the actors are welcome in this sense. The aim is an overdetermination , as described by Sigmund Freud , "the overlap" of the actor's own face with that of the character. The role should be developed slowly and with a certain "ease".

For Brecht, the arrangement of the characters on the stage, the meticulous planning of groupings and corridors, is essential for creating the space. In the position of the figures to one another, their social relationships should become clear.

“Brecht liked to go back to the model of Brueghel , whose groups are socially determined. Let us remind you of 'The Fat Kitchen' and 'The Skinny Kitchen', which are not only juxtaposed - contradicting each other - but each of which contains its own contradiction: A skinny poor man is thrown out of the crammed kitchen of the fat pans and into the In a dry kitchen (whose furniture and appliances are dry like humans), a fat paunch who has apparently made a mistake in the door is supposed to be pulled into it. "

Brecht develops the arrangement of the corridors and groupings from the content of the statement, not from abstract aesthetic considerations. How do the characters relate to each other? Which social contrasts become clear? Who is approaching someone? Who is turning away?

"Whether the interests of the characters contradict one another or whether they agree is stated in the arrangement by their moving apart or towards one another."

Käthe Rülicke-Weiler explains this with various examples: In the first scene of Mother Courage , the sergeant tries to distract the mother by buying a buckle. During this time the recruiter wants to sign the son for the military. The mother went to the sergeant and turned away from her son and thereby lost him. Brecht writes about the first act of Coriolan : “How do the plebeians receive news of the war? - Do you welcome the new tribunes? Are they crowding around her? Do you get the instruction from them? Will your attitude towards Marcius change? When the questions have been asked and answered and everything comes out on stage, the main alienations are set. "

The public

Walter Benjamin begins his definition of epic theater (1939) with the changed role of the spectator. Like the novel reader lying relaxed on the sofa, he should follow the events on stage. Unlike the novel reader, however, the audience appears as a “collective” that sees itself “prompted to respond promptly”. Furthermore, Brecht's drama is also aimed at "the masses", at "interested parties who don't think for no reason". For these spectators, the processes on stage should be "transparent" and "controllable from the experience of the audience [...]".

For Brecht, one way of getting the audience to judge what was going on on stage were courtroom scenes, which can be found in many of his plays. The viewer is put into the role of the court audience, which forms a judgment about the negotiated case. What happens on stage is a "legal case to be decided".

Brecht's directorial work included the audience from the beginning through public rehearsals by the Berliner Ensemble . He did not see the audience as a homogeneous mass, but recognized the different interests and positions of the theatergoers. The speeches to the audience should not even out the differences in the audience, but rather reinforce them. The performers should seek “contact with the progressive parts of the audience”.

Brecht's drama does not attempt to formally involve the audience in the action on the stage, but rather wants to activate them mentally, as judges. The viewer is robbed of the illusion and thereby gains the ability to relate the theater events to his or her reality. The illusion theater, as Brecht has the "philosopher" say in the "brass purchase", captivates the audience in such a way that there is no room for lustful doubt. In addition, the new questions of the time can no longer be answered through “empathy”. Society is too complex to understand how people live together through a perfect imitation of an individual's feelings and their immediate causes.

Prologues and Epilogues

The prologue and epilogue are further narrative elements that Brecht uses in various ways and that "initially take on a similar function as title, subtitle or narrator". In The Good Man of Sezuan it becomes clear in the “foreplay” that the gods see their visit to earth as an experiment: “The world can remain as it is if enough good people are found who can live a human existence.” The prologue by Mr. Puntila and his servant Matti , spoken by one of the actresses, introduces the audience to the character and intention of the production:

- “Dear audience, the times are sad.

- Smart who are worried and stupid who are carefree!

- But if you don't laugh anymore, you're not over the hill

- So we made a weird game.

- ...

- Because we're showing here tonight

- You a certain ancient animal

- Estatium possessor, called landowner in German

- Which animal, known to be very greedy and completely useless ... "

Alienation effect

The alienation effects , or “V effects” for short, are used to deprive the audience of the illusion of theater. V-effects should be the trigger for the viewer's reflection on what is represented. The viewer only thinks more intensely about what is alienated, unknown to the viewer and appearing strange, without accepting it. Only when the familiar and everyday - such as social conditions - appear in a new, unfamiliar context, does the viewer begin a thought process that leads to a deeper understanding of this fact that has actually long been known. This can be reflected, for example, in the history of people or events:

For the actor, the means of alienation, according to Brecht, is a clear “gesture of showing”. It is important for actors and viewers to control the means of empathy. The model for this form of representation is the everyday process that someone shows the behavior of another person, for example to make fun of someone. Such an imitation can do without an illusion. In order to prevent the actors from uncritically identifying with their role, long rehearsals should take place at the table. The actors should record their first impressions and contradictions of the character and integrate them into their play. Another possibility of behavior must always be indicated on the stage. The role distance in the game can be illustrated using the example of the director's game, who shows something to an actor without fully slipping into the role.

Historicization

Historization is a narrative technique that z. B. can be found in the life of Galileo . In order to draw knowledge from the social situation of the present, "a certain social system is viewed from the point of view of another social system". This enables a deeper understanding of this era compared to the current social system:

"The classics have said that the ape can best be understood from the human being, his successor in development." (Brecht, Gesammelte Werke, Volume 16, p. 610). The present opens up opportunities for knowledge about the past that were inaccessible to the people of the time. Jan Knopf explains this using Brecht's poem Der Schneider von Ulm : For the Bishop of Ulm, a tailor's failed attempt to fly is proof that no one will ever be able to fly. From today's perspective, this firm belief in the God-given limits of man appears to be a grotesque overestimation of oneself. History proves that even rigid relationships can be changed.

Another form is the historicization of the present. Knopf sees Brecht's means of questioning the present self-evident and certainties in comedies such as the petty bourgeois wedding , which exposes the present "as comical, ... as already outlived, hollow, without a future".

Walter Benjamin points out that the historicization of the epic theater has robbed the fable of tension. A well-known story is just as suitable for this as well-known historical events. Because the theater is freed in this way from the tension of the audience directed towards the end of the play, it can, like the mystery play, represent longer periods of time. Brecht's dramas report on long periods of time, the life of Galileo represented 32 years with a premiere playing time of 158 minutes, with Mother Courage , Brecht showed 12 years in 179 minutes. Käthe Rülicke-Weiler analyzes that this “tremendous shortening of events” makes a clear difference to reality. Brecht does not set the beginning or end of the fable arbitrarily: It shows that "Brecht's pieces do not start and stop at any point, but at a certain point that is essential for the plot shown". With the mother Courage, for example, the play begins with the family's march to war and ends with the loss of the last child. What is given up is the fixed arc of tension in classical drama and the hero's tragic fate, which is fulfilled through a chain of causes and consequences. In the courage, the mother gradually loses her 3 children. Each of these losses could represent a climax and turning point, but the courage does not react and continues to bet on the deal with the war.

Stage design

Brecht's long-time set designer Caspar Neher invented a stage style that matched Brecht's idea of epic theater. First, Neher investigated whether objects had a function for the plot or not. He only hinted at everything decorative and not relevant to action. When it came to important props, however, he was keen on accuracy. But even the only sketched elements had the task of conveying an impression of the world of the characters and stimulating the audience's imagination. The bright lighting, almost exclusively with white light, was used to destroy the illusion, with the spotlights being placed in a visible manner. Modifications took place with the curtain open. Neher often divided the stage into two areas. The foreground was the environment in which the game took place, painted in the background or projected an environment that was often visible throughout the play. Neher often showed contrasts, such as Mother Vlasova's small room in the foreground and the projection of a large factory in the background.

In many productions, Brecht provided the set with texts and contents in the form of posters or projections. In his Berlin production of the play Mother Courage and Her Children in 1949, the location of the action was indicated in large letters, including a brief summary of the scene. Brecht took the tension off the audience in order to enable them to pay more attention to the "how" of the events than to follow the fate of the stage characters in awe. Together with an extremely economical but carefully designed stage, Brecht hoped to activate the audience's imagination. Brecht only used technical aids and projections sparingly. An exception was the 1928 performance of Schwejk , which was jointly designed with Piscator : Two conveyor belts running in opposite directions transported actors, marionettes drawn by George Grosz and parts of the stage set across the stage, pictures or films were shown on large projection surfaces. A strange effect was achieved. Brecht regularly used the revolving stage , which was still new at the time , for quick scene changes or certain movements on the stage. Unlike Piscator, Brecht rarely worked with films.

Songs

Music and “songs” are also essential to Brecht's epic theater. The songs are involved in the dramatic plot to different degrees. In some pieces, the intersection between the scene and the song is clearly emphasized: the actor leaves the scene, the lighting and sometimes the stage design change. The actor steps in front of the curtain as a singer and performs a song. This creates a strong tension between the lyrical lyrics and the scenic representation, which opens up an additional level of reflection. In the Berlin production by Mutter Courage , Brecht visually clearly separated the songs from the rest of the stage. A "musical emblem [...] made of trumpet, drum, flag and lampballs that lit up" was let down from above in the songs, and more and more "torn and destroyed" during the course of the performance. The small music ensemble was in a box, clearly separated from the stage. The songs - so Brecht - should be "interludes", not grow out of the plot. Nevertheless, the songs in Mother Courage are much more closely integrated into the plot than in earlier plays and productions, such as the Threepenny Opera . They are also aimed at a figure in the scene.

Walter Hinck considers these addressees to be "fictitious" with the exception of the "Song of the Great Surrender". Only there does the song change the plot, the other songs "do not affect the plot itself", they "reach into the exemplary". Hinck concludes from these observations that even in the courage “none other than the spectator [...] is the addressee of the instruction or warning”. In the piece The Good Man of Sezuan , Brecht dispenses with fictional addressees of the songs, perhaps with the exception of the song from the smoke. According to Hinck, the songs, like the piece, are parabolic- oriented. Despite such differences, the singers have a "dual value" in common: "On the one hand, he remains a figure in the aesthetic-scenic space, on the other hand he becomes a partner of the audience".

composition

The composition itself should also have a distancing effect, which should not be "mainly catchy". The listener must first “unite the voices and the manner”. Brecht worked with various composers, but regularly with Paul Dessau , Hanns Eisler and Kurt Weill . The music itself is full of tension due to the peculiar mixture of new music and twelve-tone technique with folk elements. The music not only has the task of accompanying the songs, but also comments on the scene. The main focus is on contrasts.

“Music had neither to 'background' in order to serve the 'word', the plot (as in the film), nor to suppress the word by making it inaudible and insignificant (as in the old opera). Even where music and word meet, both should be heard separately: the word should remain understandable [...], the music should have independence, not be subordinate to the word, but rather give it a certain attitude ('gesture'), to make aware of its meaning, to comment on it or to put it into perspective. "

Epic theater is also intended to be entertaining in the field of music in the sense that productivity is entertainment. For Brecht, the aspect of entertainment consisted in the thought and reflection process while listening. For the corresponding music he introduced the name Misuk .

Brecht worked regularly with Kurt Weill in the musical field . Weill had already started in 1925 to incorporate elements from revue, popular dance music and jazz into his compositions. After texts by Yvan Goll and Georg Kaiser , he had tried out new forms. The first product of the cooperation with Brecht was the new setting of the mahogany chants . The Threepenny Opera was their greatest success . Brecht's share in the musical design is unclear, but it is assumed that he had an influence on it. Weill and Brecht agreed that the gestural character of the songs was a central concern.

Brecht worked with the composer Hanns Eisler parallel to Weill and after separating from Weill until his death. Eisler composed z. B. the music to measure (1930) and to mother (1932) and was politically close to Brecht. Brecht expected Eisler to "give the music a consciously 'sensible' character", to gain distance from the strong emotional values of the music. For Eisler, this “rational music” was initially difficult to accept. Features were the distance from the musical staging of the "bourgeois concert halls", not "emotional confusion", but "striving for reason".

The third composer with whom Brecht worked for a long time was Paul Dessau . B. created the music for Mother Courage and her children , Mr. Puntila and his servant Matti and The Condemnation of Lukullus . Dessau's adherence to the twelve-tone technique and his sympathy for Arnold Schönberg and other avant-garde composers led to violent disputes in GDR cultural policy.

→ see also the article on the various settings of the piece Mother Courage and Her Children (setting)

Marxist reception

Walter benjamin

Between 1930 and 1939, Brecht's friend Walter Benjamin wrote a series of short texts on epic theater and on Brecht's literary policy, most of which remained unpublished at the time. Benjamin visited Brecht in Denmark several times during his exile; they met in Paris or in southern France and looked for joint work opportunities. Benjamin's essay The work of art in the age of its technical reproducibility (1935) analyzed the consequences of technical developments for art. With regard to Brecht, he was interested in the changed role of the author due to the changed productive forces and ownership structures in the cultural sector. With publishers, magazines and other publication options, ownership has always been important for culture. But film and radio create a new quality insofar as quasi-industrial structures have developed here. As a result, the influence of capital is strengthened, the authors get into conditions of exploitation that dictated their working conditions. This development also affects areas that are not directly controlled by the media. Readers of novels and short stories change their reading habits if they watch films regularly.

Brecht has dealt intensively with radio and film, radio plays and films such as 1932 Kuhle Wampe or: Who Owns the World? produced. Brecht not only used this experience technically in his drama, for example through projections, but also further developed the pieces themselves, for example implemented the radio's demand that “the audience must be able to join in at any time” through the independence of the parts. Benjamin metaphorically connects Brecht's literary “experiments” with terms from industry. “How an engineer starts drilling petroleum in the desert, takes up his work at precisely calculated points in the desert of the present”, is how Brecht plans innovations, assembling people like in the play Man is Man (UA 1926) like the worker a car. The author becomes a "producer". For Benjamin, this means that the author not only takes a position outside of his works, but also changes his writing himself and the cultural institutions. He cites Brecht, who has demanded that as an author one should not simply supply the production equipment, but rather begin to convert it. The redesign of the theater as an institution is intended to attract a different audience, the “proletarian masses”. Like radio, the theater must attract a working-class audience who, by presenting their problems, are able to understand and judge the play.

The epic theater depicts social conditions by repeatedly interrupting the flow of the plot. This turns the theater into an “experimental arrangement” that amazes the audience. Benjamin explains the V effect in a way reminiscent of Sartre : a simple family scene is shown. Each family member gestures to demonstrate their share in a conflict. “At this moment the stranger appears in the door. 'Tableau', as they used to say around 1900. That means: the stranger now encounters the condition: crumpled bedding, open windows, devastated furniture. ”The devastation of our social order becomes visible by being depicted in an alienated way, stopped, exposed to a critical view from a clear distance.

Evaluation by Western Marxists

Theodor W. Adorno - criticism of the 'committed' theater Brecht

Adorno sees the glorification of the sacrificial death of an individual for a collective as a danger in modern art. Modern authors and composers chose the aestheticization of sacrificial death “so that art can identify with the 'destructive authority'. The collective that is conjured up consists in the fact that the subject crosses itself. ” Stravinski's composition for the ballet Le sacre du printemps from 1913 is Adorno's first example of this danger: in order to appease the god of spring, the piece becomes one chosen virgin sacrificed. The parallel to the victim motif in many of Brecht's pieces goes further: the victim brings about his own death through an ecstatic dance. Adorno makes a reference to Brecht's didactic play Der Jasager , in which a sick boy voluntarily sacrifices himself so as not to stop an expedition:

“One single remark about Stravinsky makes it clear that modernism is at stake: 'He is the yes-man of music.' Adorno's allusion to Brecht's didactic piece is more than a connotation: it hits the nerve of a whole complex within modernity that includes the most varied of forms of aestheticization of the repressive. "

Adorno's criticism of Brecht is based on the political statement, but sees the form as contaminated by the untruth of these statements. According to Adorno, Brecht's aesthetic is inextricably linked with the political message of his pieces. The glorification of the communist party and the justification of the Moscow show trials in the dramatization of Maxim Gorki's mother or the measure "tarnishes the aesthetic figure". The "Brechtian tone" is "poisoned by the untruth of his politics". Brecht's advertisement for the GDR is based on the lack of recognition that this system is not "just an imperfect socialism, but a tyranny in which the blind irrationality of the social play of forces returns ..."

Brecht himself reflected on the sacrifice of the individual for a collective in a typescript that was created around 1930:

“A collective is only viable from the moment and for as long as the individual lives of the individuals united in it do not matter.

??? (Question mark in the text)

People are worthless to society.

Human help is not common.

Nevertheless, help is given to them, and although the death of the individual is purely biologically uninteresting for society, dying should be taught "

The commentary of the complete edition suggests an interpretation of this quotation as a literary attempt. The three question marks questioned the absolute primacy of the collective over the individual. Nevertheless, Adorno Brecht's didactic pieces were not the only ones who interpreted them in this sense.

The legitimation of the victim in Brecht plays is reflected in the form, in the language. The “wild roar of the ' measure '” conceals the contradictions as well as constructed roles, such as characters like the “fiction of the old peasant saturated with epic experience” in the linguistic gesture of wisdom. The linguistic design of the oppressed, to whom the message of an intellectual is put in their mouth, is "like mockery of the victims". "Anything is allowed to play, only not the proletarian."

Like Brecht, Adorno Lukács' literary theory and socialist realism , "with which for decades one has choked off every unruly impulse, everything that apparatchiks incomprehensible and suspicious", has always sharply criticized. Nevertheless, he saw no alternative in Brecht's theater concept either. In an essay on Lukác's theory of realism from 1958, he criticized Brecht's historical farce The Temporary Rise of Arturo Ui , which satirically compares the rise of Hitler with that of the gang boss Al Capone , as a trivializing approach to reality. The portrayal of " fascism as a gangsterism" and the supporters from the industry as "cauliflower trust" are unrealistic.

“As a company of a kind of socially extraterritorial and therefore arbitrarily 'stopping' gang of criminals, fascism loses its horror, that of the great social train. This makes the caricature powerless, silly by its own standards: the political rise of the minor criminal loses its plausibility in the play itself. "

In 1962, he took up the topic again in a radio report on the criticism of politically active literature. The reason for the trivialization of fascism is the political aim of the play: “This is how the agitational purpose dictates it; the opponent must be downsized, and that promotes the wrong policy, in literature as well as in practice before 1933. "

Adorno's criticism of Brecht is based on a deep distrust of “committed” literature. Only autonomous art is able to oppose the social forces. After the “abdication of the subject”, “any commitment to the world must be terminated”, “so that the idea of a committed work of art is sufficient ...” Brecht correctly recognized that empathy and identification and the portrayal of society in the fate of an individual person is the essence of modern society. That is why he switched off the concept of "the dramatic person".

“Brecht distrusts aesthetic individuation as an ideology. That is why he wants to relate the social mischief to the theatrical appearance by pulling it bald outward. The people on the stage visibly shrink into those agents of social processes and functions that they indirectly, without suspecting it, are empirically. "

Brecht's attempt to paint a realistic picture of capitalism on the stage failed not only because of the trivialization of the “concentration of social power” in fascism, but also because of the dishonesty of his political statements. Brecht's play Saint Joan of the Slaughterhouses , which depicts the crises of capital and their social effects, is characterized by political naivete. Adorno criticizes the derivation of the crisis from the sphere of circulation , i. H. from the competition of the cattle dealers, which misses the real basic economic structures. He thinks the image of Chicago and the portrayal of the strike are unbelievable. Brecht's attempt to use the Thirty Years' War as a parable for the Second World War in Mother Courage also failed . Since Brecht knew "that the society of his own age is no longer directly tangible in people and things", he chose a "faulty construction". "Politically bad becomes artistically bad and vice versa."

Gerhard Scheit sees Brecht's victim ideology as a recourse to forms of bourgeois tragedy. As in Lessing's drama Emilia Galotti , “bourgeois society demonstrated the victim primarily through the fate of the woman: it is the young lover or the daughter who not only has to die but also asks to be killed, as in the daughter the father, so as not to end up in the arms of the class enemy contrary to virtue 〈…〉 Brecht's pupils and young comrades are the proletarian heirs of the bourgeois virgin; the revolutionary party takes the place of the virtuous father. "

Scheit concretises Adorno's criticism in relation to form. The victim of the young comrade in the measure leads to a de-individualized drawing of the figure of the victim, Hanns Eisler himself characterized his music for the measure as "cold, sharp and cutting". Scheit speaks of a “ritualization of extermination” in Brecht and Eisler. Eisler himself considered this tendency to be dangerous, “because it undoubtedly makes the process ritual, ie it moves away from its respective practical purpose.” The suppressed fear creates a false pathos , “the audience and the performers should feel cold, when the young girl is sacrificed and the young comrade wiped out - a strangely infantile glee, or rather a joy in the fear of others, should have really spurred the artists on. ”Against Adorno, Scheit argues in favor of Brecht that epic theater is the contradiction of the audience myself provoked:

“What distinguishes Brecht's epic theater, however, is that it provokes the possibility of such an objection itself and takes up this objection again and again as an impulse: for example, even before Eisler's criticism, there was a protest from students when studying the Yesager in a grammar school in Berlin-Neukölln [the later Karl Marx School] led to a real reworking - to the creation of two other pieces: The Yes Man and The No Man . The pupils simply did not see why the boy in the play should be thrown into the abyss by the others without concrete reasons - just because the 'great custom' demands it - and should say yes to it himself. "

The question of whether the form and content of the measure is to be read as a political justification for the Stalinist terror or as an extreme provocation that calls for opposition remains controversial to this day. In the posthumously published Aesthetic Theory , Adorno's criticism of Brecht is more nuanced. Adorno admits that Brecht's innovations in the theater concept "overturned the tortured psychological and intrigue theater" and "made the drama anti-illusory". The quality of Brecht lies in these innovations, "in the disintegration of the unity of the meaningful context", but not in the political commitment that "shatters" his work of art.

Louis Althusser

The French philosopher Louis Althusser , a member of the French Communist Party (PCF) and heavily influenced by structuralist theory, saw in Brecht's epic theater an analogy to the revolution of philosophy by Marx . Just as Marx said goodbye to speculative philosophy, Brecht revolutionized the culinary theater created for mere consumption. Brecht's alienation effect is not just a theatrical technique, but a shift in the political standpoint towards partisanship.

Althusser is now looking for places in the structure of the theater where a shift in point of view can take effect. First he mentions the destruction of the illusion that theater is life, from which he bases the principles of epic theater. Furthermore, the theater had to move the center of the play outwards, just as Brecht did not allow his Galileo to speak the big words “And it does turn!”. The distanced acting of the actors as an important means of epic theater should not be made independent as a technique, but should serve the goal of tearing the audience out of identification and encouraging them to take sides. According to Althusser, however, the theater revolution is reaching its limits. According to Brecht, the theater has to show something concrete in the behavior of the actors and entertain. Brecht sees the viewer's pleasure essentially in the gain of knowledge. However, this explanation briefly transfers a principle of science to theater.

According to Althusser, the matter of the theater is ideology , the aim is to change the consciousness of the audience. The traditional theater reflects and confirms the self-image of the audience and the "myths in which a society recognizes itself (and in no way recognizes itself)" by reproducing them "in the mirror consciousness of a central figure unbroken". Now Brecht has recognized that no stage figure can represent the complex social conflicts. Knowledge of society is only possible through the confrontation of a consciousness with “an indifferent and different reality”. Brecht brings the social contradictions to the stage by juxtaposing various “structural elements of the play”.

In Mother Courage and Her Children , Brecht confronts a number of figures biased in their ideology and their relationships “with the real conditions of their existence”. None of these characters is able to see through this complex reality or to embody it. Only the viewer could gain this knowledge. Brecht wanted "to turn the viewer into an actor who would complete the unfinished piece - in real life".

Althusser sees the role of the viewer as a problem. Why shouldn't the same apply to the audience as to the performers on stage? When a theater hero is no longer able to represent and understand the complex society, how should this be possible for the audience? Althusser sees two paths that are blocked. Just like the characters on the stage, the audience is caught up in the illusions and myths of ideology. But also the second path, identification, is closed to the audience by Brecht's epic theater concept. Althusser, who, like Brecht and Adorno, disliked the autonomy of the subject and the possibilities of individual consciousness vis-à-vis objective processes, relies here on the effect of the piece against stuck illusions:

“If the theater, on the other hand, has the shaking of this untouchable image, the setting in motion of the immobile (this immutable sphere of the mythical world of illusory consciousness), then the play is entirely a process, then it is the production of a new one Consciousness in the viewer, unfinished like any consciousness, but driven further and further by this incompleteness as such [...]. "

Confrontation with “Socialist Realism” in the Soviet Zone and GDR