Mother Courage and her children

| Data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Mother Courage and her children |

| Genus: | Epic theater |

| Original language: | German |

| Author: | Bertolt Brecht |

| Publishing year: | 1941 |

| Premiere: | April 19, 1941 |

| Place of premiere: | Schauspielhaus Zurich |

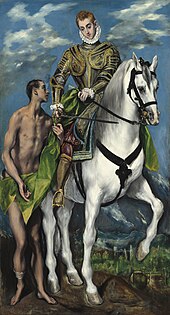

| Place and time of the action: | Thirty Years War between 1624 and 1636 |

| people | |

|

|

Mother Courage and Her Children is a drama written by Bertolt Brecht in exile in Sweden in 1938/39 and premiered in Zurich in 1941 . It takes place in the Thirty Years' War between 1624 and 1636. It tells the story of the sutler Mother Courage, who tries to do her business with war and loses her three children in the process. The event can be understood as a warning to the common people who hope to deal with the Second World War through skillful action . At the same time it sends a warning to the Scandinavian countries, where companies hoped to make money on World War II. But Brecht's intentions go beyond that: he wants to convey disgust for the war and for the capitalist society which, in his opinion, produces it.

The mother Courage is still exemplary for Brecht's concept of epic theater . The audience should analyze the events on stage in a critical and distanced manner, not experience the fate of a positive hero with feeling. Brecht made the performance of the Berliner Ensemble with the "Courage model", a collection of photos, stage directions and commentaries, a temporarily mandatory template for numerous performances around the world. The drama was set to music several times and filmed by DEFA in the style of the Brecht staging. During the Cold War , theaters boycotted the play in some western countries.

Nevertheless, Mother Courage was a great stage success, almost every city theater tried its hand at Courage, as many directing stars, such as Peter Zadek , as Brecht at the Deutsches Theater, or Claus Peymann with the Berliner Ensemble. For many actresses, courage is a prime role. The drama is widely used as school reading.

content

Brecht has repeatedly developed and changed the piece. The table of contents follows the print version from 1950 with 12 scenes, the same text as the Berlin and Frankfurt complete editions.

First picture

In the spring of 1624, Mother Courage joined the 2nd Finnish regiment as a sutler with her three children , which recruited soldiers for the campaign in Poland in the Swedish countryside of Dalarna . A sergeant and a recruiter are supposed to recruit soldiers for their field captain Oxenstjerna . The sergeant claims that peace is sloppiness and only war can bring order.

When the sergeant stops the Courage car with her two half-grown sons, the recruiter is happy about two "tough men". Courage introduces itself as a cunning businesswoman with a song. Her real name is Anna Fierling. She got her nickname “Courage” when she drove fifty loaves of bread under the fire of the guns into the beleaguered Riga to sell them before they went moldy.

When she is asked to identify herself, Courage presents some “documents”: a missal to wrap cucumbers, a map of Moravia and a certificate of a disease-free horse. She says that her children were conceived by different men on the military roads of Europe. When she realizes that the recruiter is after her sons, she defends them with the knife. As a warning, she lets the sergeant and her children draw lots that prophesy death in war for everyone.

Ultimately, she lets herself be distracted by her business acumen when the sergeant shows interest in buying a buckle. She ignores the warning sounds of her mute daughter Kattrin, and when she returns, the recruiter has gone away with her eldest son Eilif.

Second picture

Mother Courage pulls in the years 1625 and 1626 in the entourage of the Swedish army through Poland. While she is negotiating a capon with the captain's cook , she overhears her son Eilif being honored by the captain for a heroic deed. Eilif and his people were looking for cattle to steal from the farmers. In doing so, she caught a majority of armed peasants. But by cunning and deceit, Eilif managed to knock down the peasants and steal the cattle. When Courage hears this, she slaps Eilif because he did not surrender. She fears for her son because of his boldness. In the double scene, the viewer can watch what is happening in the kitchen and at the field captain's at the same time.

Third picture

Three years have passed. Courage trades for bullets with the equipment master of a Finnish regiment. Her youngest son Schweizerkas has become paymaster and administers the regimental treasury. Courage warns her son not to act dishonestly.

Courage meets the warehouse whore Yvette Pottier, who tells her her life story (song about fraternization) . Yvette explains her decline with the fact that she was abandoned by her first great love, a cook named "Pfeifen-Pieter". She is avoided by the soldiers because of a venereal disease. Despite all the warnings about being a soldier, Kattrin plays with Yvette's hat and shoes.

Afterwards, the cook and field preacher talk about the political situation. The chaplain claims that falling in this war is a mercy because it is a war of faith . The cook replies that this war is in no way different from other wars. It meant death, poverty and calamity for the affected population and gain for the masters who waged the war for their benefit.

The conversation is interrupted by the thunder of cannons, shots and drums. The Catholics raid the Swedish camp. In a mess, Courage tries to save her children. She smeared Kattrin's face with ashes to make her unattractive, advised Schweizererkas to throw away the cash register, and gave the military preacher shelter. At the last minute she takes the regimental flag from the car. But Schweizererkas wants to save the regimental treasury and hides it in a molehole near the river. However, Polish spies notice that his belly protrudes strangely through the hidden cash register and arrange for his arrest. Under torture, he confesses that he has hidden the cash register; but he does not want to reveal the location. The Chaplain sings the Horen song .

Yvette has met an old colonel who is willing to buy Mother Courage's car so she can buy her son out. Courage secretly hopes for the money from the regimental treasury and therefore only wants to pawn the car. But she has been negotiating too long about the release price for her son, and Schweizererkas is shot by the Polish Catholics. When the corpse is brought in, the mother Courage denies her son in order to save herself.

Fourth picture

Mother Courage wants to complain to a Rittmeister because soldiers have destroyed goods in their car while searching for the regimental treasury. A young soldier would also like to complain because he did not receive the money he had promised. Then Courage sings the song of the great surrender , which expresses deep resignation and surrender to the mighty. The two waive the complaint. The quote in the chorus of the song, alienated by a colon: “Man thinks: God directs” demonstrates the turning away from religion and the ideology of war.

Fifth picture

Two years have passed. Courage has crossed Poland, Bavaria and Italy with her car. 1631 Tilly wins near Magdeburg . Mother Courage stands in a blasted village and pours schnapps. Then the field preacher comes and demands linen to bandage wounded peasants. But Courage refuses and must be forced by Kattrin and the field preacher to help. Kattrin rescues an infant from the collapsing farm at risk of death.

Sixth picture

In 1632, Courage attended the funeral of the fallen imperial field captain Tilly in front of the city of Ingolstadt . She entertains some soldiers and fears that the war will soon end. But the field preacher calms them down and says that the war is going on. Courage sends Kattrin into town to buy new goods. While her daughter is away, she rejects the field preacher, who wants more than just a flat share.

Kattrin returns from town with a disfiguring wound on her forehead. She was ambushed and mistreated, but did not allow the goods to be taken away. As a consolation, Courage gives her the shoes of the warehouse whore Yvette, who the daughter does not accept because she knows that no man will be interested in her anymore.

Kattrin overhears her mother's conversation with the field preacher from the car. According to Mother Courage, Kattrin no longer needs to wait for peace, because all her future prospects and plans have been destroyed with the attack and the remaining scar. No man would marry a mute and disfigured person. Her mother's promise that Kattrin would have a husband and children as soon as peace came seems to have become obsolete. At the very end of the scene, Mother Courage lets herself be carried away to the sentence: "The war should be cursed."

Seventh picture

The antithesis at the end of the sixth picture follows immediately at the beginning of the seventh: "I will not let you ruin the war", says Mother Courage. She moves "at the height of her business career" (Brecht) with Kattrin and the field preacher on a country road. In the short scene she justifies her unsettled way of life as a sutler in war with a song.

Eighth picture

The Swedish king Gustav Adolf is killed in the battle of Lützen . The bells are ringing everywhere and the rumor spreads with lightning speed that it was now peace. The cook reappears in the camp and the field preacher puts on his robe again. Mother Courage complains to the cook that she is now ruined because, on the advice of the field preacher, shortly before the end of the war she bought goods that are no longer worth anything.

There is a dispute between the cook and the field preacher: the field preacher does not want to be pushed out of the business by the cook because otherwise he cannot survive. Courage curses peace and is then referred to by the field preacher as the “ hyena of the battlefield”. Yvette, who has been the widow of a noble colonel for five years and who has become older and fatter, comes to visit. She identifies the cook as "Pfeifen-Pieter" and characterizes him as a dangerous seducer. He believes (wrongly, as it later turns out) that his reputation with Mother Courage has fallen sharply as a result. Courage drives into town with Yvette to quickly sell her wares before prices drop. While Courage is gone, the soldiers demonstrate Eilif, who is to be given the opportunity to speak to his mother. He continued to rob and murder; however, he did not notice that this is now, in "peace", considered robbery and murder. Consequently, he is to be executed. Because of the mother's absence, Eilif's planned last conversation with her does not take place. Shortly after his departure, Mother Courage returns. She did not sell her goods because she saw that fighting had started again and that the war would continue. The cook does not tell her that Eilif is to be executed. Courage moves on with her car and instead of the field preacher takes the cook with her as an assistant.

Ninth picture

The war has been going on for sixteen years, and half of Germany's inhabitants perished. The country is devastated, the people are starving. In the autumn of 1634, Courage and the cook tried to beg for something to eat in the Fichtel Mountains . The cook tells the courage of his mother, who died of cholera in Utrecht . He has inherited a small economy and wants to move there with courage, as he longs for a quiet and peaceful life. At first, Mother Courage seems to be taken with this plan, until the cook tells her that he doesn't want to take Kattrin with him. After he made it clear that the economy could not feed three people and that Kattrin would drive away the guests with her “disfigured face”, Mother Courage changed her mind. She can just stop Kattrin, who has overheard this conversation and secretly wants to run away. Mother and daughter move on alone, and the cook is puzzled to see that he has been left behind.

On the one hand, the courage is incapable of expressing her feelings, and probably assumes that her daughter only knows her as a businesswoman - hence the concealment of her motherly feelings - on the other hand, her decision is thoroughly calculating: she is aware that the car and his Function in war is simply their world. So basically she can only choose Kattrin and the war.

Tenth picture

For the whole of 1635, Mother Courage and her daughter wandered the highways of Central Germany and followed the ragged armies. You will pass a farmhouse. You hear a voice that sings of the safety of the people with a perfect roof over their heads (A rose has struck us) . Mother Courage and Kattrin, who do not have this security, stop and listen to the voice, but then move on without comment.

Eleventh picture

In January 1636 the imperial troops threatened the city of Halle . Courage went into town to shop. An ensign and two mercenaries enter the farm, where Courage has her covered wagon with her daughter. The soldiers force the farmers to show them the way into the city, as the residents, who are not yet aware of the danger, should be surprised. When Kattrin heard of the danger, she took a drum, climbed onto the roof and pulled the ladder up to her. She beats the drum and doesn't let any threats stop her. The soldiers force the peasants to drown out the drums with ax blows. When this fails, Kattrin is shot by the soldiers. But the brave effort that cost her life is successful. The townspeople have woken up and are sounding the alarm.

Twelfth picture

The next morning the Swedes leave the farm. Mother Courage returns from town and finds her dead daughter. At first she thinks she is asleep and finds it difficult to grasp the truth. She gives the peasants money for the funeral and follows the army alone with the wagon. She believes that at least Eilif is alive and sings the third verse of the opening song.

Origin of the piece

Literary influences

According to Margarete Steffin's notes , Brecht was inspired in Swedish exile by the story of the Nordic sutler Lotta Svärd from Johan Ludvig Runeberg's " Fähnrich Stahl " to write Mother Courage, which only lasted 5 weeks. Various references by Brecht to preliminary work show that in the autumn of 1939 Brecht only "wrote the first complete version". Brecht himself later states that he “wrote the piece in 1938”. In the context of the Copenhagen performance in 1953, he recalls that the play was performed in Svendborg , i. H. before April 23, 1939 when he left Denmark.

In Runeberg's ballads we find the type of maternal sutler who takes care of the soldiers in the Finnish-Russian war of 1808/09 . In terms of content, Brecht's drama bears no resemblance to Runeberg's work, which idealistically glorifies Finland's struggle for national autonomy.

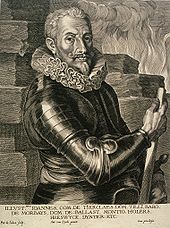

Brecht took the name "Courage" from the novel Trutz Simplex : Or detailed and wonderfully strange biography of the Ertz Betrügerin and Landstörtzerin Courasche (1670) by Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen , who uses the example of a gypsy woman to describe how the turmoil of the Thirty Years' War became moral and human Lead to neglect.

Grimmelshausen's novels relentlessly portray the horrors of war. His main work The adventurous Simplicissimus , a picaresque novel , is the first volume in a trilogy that also includes the Courasche novel and The strange Springinsfeld . Brecht, who valued Grimmelshausen because of its unheroical portrayal of the war, took over neither the plot of the Courasche novel nor the character of the title character. At Grimmelshausen, Courasche is a soldier whore with a strong erotic charisma, she is sterile (but has seven different husbands; see the three different fathers of Eilif, Schweizererkas and Kattrin) and is of high birth. The term "Courasche" does not mean courage, but the vagina :

- "But when the sermon was at its best and he asked me why I had done my opposite in such a horrible way, I replied:" Because he has seized my courage where no other man's hands have yet come ""

Nevertheless, there are indirect parallels between the two literary figures. Like Brecht's Courage, Grimmelshausen's “Courasche” also goes to war on purpose. In men's clothing, she looks for opportunities to live out her lust for rubbish and greed for money. Neither of them believe in religion. On the other hand, Courasche tries to earn her money as a soldier whore, mainly through a chain of short-lived marriages, an aspect of her personality that Brecht finds in the figure of Yvette Pottier.

Against the backdrop of the Thirty Years' War , Brecht wants to warn against war in general and to uncover its causes. The historical background of the drama, the design of the war as a civil war, comes from Grimmelshausen. Jan Knopf sees aspects of the figure of Simplicissimus in the figure of Eilif and continues to refer to formal influences from Grimmelshausen: like this in Simplicissimus, Brecht precedes the events in his drama with brief summaries of the content of the events in order to reduce the "tension of the reader about the" what " Whether-at-all-tension) on the "how" (how-tension), that is, from the mere material to its assessment ”. What served the moral evaluation of events in the Baroque era is, in Brecht's work, a means of bringing about a distanced gaze from the audience. The audience should understand and judge the events, not experience them with empathy and anticipation. Jan Knopf also sees the influence of the cinema in the short synopsis, which worked excessively with overlaid texts in silent films and “in the 'epic film' of the 1930s”.

Research sees a further influence of Grimmelshausen in the concept of the “reversal of the ordinary: in the Baroque it is the topos of the inverted world versus the divine world order […], with Brecht it is the“ revaluation ”of the“ normal ”bourgeois values through the war : as the new normal. "The Simplicissimus also shows the commercial interest in war:

- “Now, dear Mercuri, why should I give you peace then? Yes, there are quite a few who want him, but only, as I said, for the sake of their belly and lust; on the other hand there are also others who want to keep the war, not because it is my will, but because it wins them over; And just as the bricklayers and carpenters want peace so that they can earn money building the cremated houses, so others who do not dare to support themselves in [405] peace with their manual labor demand to steal the continuation of the war in it. "

References to the political situation of the time

Brecht wrote his piece in exile "for Scandinavia". The involvement of Scandinavia in the war is already indicated by the historical link to the Thirty Years' War. "The first two pictures in particular reveal the intended Swedish audience, since the Swedish-Polish war (which precedes the intervention of the Swedish king in the Thirty Years' War ) forms the historical backdrop." Brecht's main intention was to warn his hosts that to get involved in business with Hitler. Brecht writes:

“It may be difficult today to remember that there were people in Scandinavia back then who were not averse to getting a little involved in the ventures across the border. You will hardly talk about it. Not so much because it was a raid, but because the raid failed. "

As early as 1939, with two one-act plays, Brecht had criticized Denmark's neutrality (“Dansen”) and Sweden's ore deals with Germany (“What does iron cost?” Under the pseudonym John Kent). With Mother Courage, he hoped to influence the Scandinavians' attitude towards theater.

"As I wrote, I imagined that from the stages of some large cities the playwright's warning would be heard that he must have a long spoon who wants to have breakfast with the devil."

The topics of nationalism and racism are also related to the time . Mother Courage confidently introduces her children as a multinational society. More than the biological heritage of the fathers from different nations, she rates the influence of her changing husbands from different countries with whom the children grew up. Against all racial doctrine , Courage sees her family as a pan-European mixture:

“Eilif stands for bold, autonomous, self-reliant Finland, which in 1939 distanced itself from both Germany and the Soviet Union in the hope of being able to 'stay out of it'; Schweizererkas stands for the 'Swiss cheese', the nation of the merchant farmers and their famous neutrality ... and Kattrin for the halved German who is condemned to silence ... "

Probably the clearest reference to the time of the drama can be seen in an allusion to Hitler's attack on Poland in the third scene.

- Mother Courage : “The Poles here in Poland shouldn't have interfered. It is true that our king has entered with them with "horse and man and chariot", but instead of the Poles having maintained the peace, they interfered in their own affairs and attacked the king as he walked along calmly . So they are guilty of a breach of the peace, and all the blood comes on their heads. "

The quote links and updates various aspects beyond the reference to Hitler's attack on Poland that opened World War II. The biblical threat of vengeance "The Lord let his blood come on his head because, without my father's knowledge, he knocked down two men who were more just and better than him and killed them with the sword" prophesies a punishment in the satirical representation of courage Sacrifice. Such satirical elements "expose the illogic of the National Socialist logic by over-understanding it satirically." The quote "with horse and man and car" comes from an old war song that was composed in Riga in 1813 .

Elsewhere, too, the Nazi ideology is targeted with bitter humor. The link occurs, for example, through the connection between the “religious war” and the ideologically based Nazi war. Brecht lets the field preacher rave about his power of persuasion and about the final victory : “You haven't heard me preach yet. I can only put a regiment in such a mood with one speech that it looks at the enemy like a sheep-hearth. Their life is to them like an old, stifled rag that they throw away in thought of the final victory. God has given me the gift of speech. "

The cook makes the reference to the brutality of the conditions in Germany, for which the Swedish king is held responsible in the historical context:

- The cook : “... the king allowed himself to taste enough freedom, where he wanted to import it into Germany ... and then he had to lock up the Germans and have them cut into four because they held on to their bondage to the emperor. Of course, if someone did not want to become free, the king had no fun. At first he only wanted to protect Poland from bad people ... but then the appetite came along with food and he protected all of Germany. "

Here, not only is the Polish campaign addressed again, but also the Nazi concept of protective custody , which brought opposition members to the concentration camp under the pretext of having to protect them from “popular anger”.

Brecht's doubts about freedom in democratic capitalist societies are also expressed in various polemics. “Brecht was skeptical about the freedom that the bourgeoisie pretended to represent,” writes Fowler, referring to Brecht's drama and the “ anachronistic streak ” and derision there of “freedom and democracy”. In the play, according to Fowler, freedom appears as slavery, for example in the form of oppression and exploitation by conquerors like the Swedish king.

Despite these and other references to Europe under National Socialism, Courage is not a key drama. With ambiguities and a few terms from the language of 1939, Brecht set “signals” for possible updates, but these “did not play a major role in the play”.

Performances and text variants

The world premiere in Zurich

The premiere of Mother Courage took place on April 19, 1941 at the Zurich Schauspielhaus , directed by Oskar Wälterlin . The Piscator student Leopold Lindtberg directed , the music composed Paul Burkhard , who also conducted himself. Therese Giehse played the main role. The simple stage set designed by Teo Otto was formative for all subsequent performances of the play and for the model later developed by Brecht, although Brecht was never able to see the Zurich performance in person.

At the center of the staging was the Courage car, which gradually descended during the course of the performance. The simple set design was limited to flickering backgrounds on stretched canvases, simple wooden stalls, in front of which landscapes were suggested. For the performance, Brecht wrote the content summaries before the individual scenes, the “titularium”. The Zurich program booklet interpreted Mother Courage as Brecht's return from the didactic pieces to human theater: “The human-compassionate, the spiritual-empathic is the focus in this poem - when the formal elements of the 'epic' theater are taken up… The characters no longer represent ‹Views›, no more opinions ... “Despite the great impact of the play, there were only ten performances, which, in the opinion of the theater scholar Günther Rühle, had such a long lasting effect as no other play or production that was performed in exile.

In 1941, the contemporary critic Bernhard Diebold recognized the concept of the Threepenny Opera in the Zürcher Courage . Brecht build "his tragicomic Carnival Booth, into the higher as a ballad singer mocks his satire [...] and sings in favor of the little ones in the crowd and against the great ones who make their war on spiritual and temporal thrones. '" Less likely Brecht liked have that Diebold saw in Courage above all "a warm-blooded mother animal" who had "no choice": "One is unfree like a poor animal." Diebold sees in Brecht's owl mirroring, in his "fool morality", no positive perspective, Brecht's play serves "only the nihilistic devaluation of all belief in culture" The critic misses - like later the criticism from the point of view of socialist realism - the positive hero figure "who is supposed to slay the evil dragons of humanity for humanity's sake." Diebold's praise for Therese Giehse's portrayal of Mother Courage may have been one of the reasons why Brecht later removed the negative sides of the figure through text changes and Re gie emphasized:

“But Therese Giehse, with her great mother's heart, stood beyond all historical claims in eternity. No matter how disrespectful she might moan against the 'higher' and let her business acumen play, she never became the 'hyena of the battlefield'; and the roughness of the sutler, required by the harsh circumstances, receded almost too much behind the radiation of her feelings and her moving pain when she had to lose the children one by one. "

Other critics of the time also interpreted the Giehse's courage primarily as a mother figure. The critic of the Basler National-Zeitung speaks of the “nursing mother” courage that she was for her children as well as for cook and field preacher. "Like the prototype of the primal mother, the mother courage embraces everything that comes near her with maternal care [...]." From this point of view, courage appears as a representation of "millions of mothers of the present" who, despite all adversity, "unbroken [ …] Out into the hard life ”.

Fowler shows that from the moment of the premiere in Zurich, two competing interpretations pervade the history of reception: the condemnation of courage - in the sense of Brecht - due to her participation in the war and, in contrast, the defense of courage as an innocent victim or a suffering mother. In retrospect it can be said about the premiere that at its time, spring 1941, the end of Nazism - naively seen - was by no means clear.

The performance of the Berliner Ensemble

Preparations and first contacts to Berlin

On October 24, 1945, the chief dramaturge of the Deutsches Theater, Herbert Ihering , asked Brecht for permission to perform for Mother Courage:

“I'm with Wangenheim at the Deutsches Theater. […] There are very nice options here. Erich Engel wants to go to Berlin, but is still provisional director of the Münchner Kammerspiele. […] Dear Brecht, come soon, so that you can see how many good and Brecht-enthusiastic actors we still have at the Deutsches Theater, and with what enthusiasm we all want to plunge into the wonderful Mother Courage. "

Helene Weigel sent a package of groceries, but there was no reply from Brecht. In December 1945 Brecht wrote to Peter Suhrkamp and expressed his skepticism towards theater in Germany: “The reconstruction of German theater cannot be improvised. You also know that, even before the Hitler era, I found it necessary to get very involved in the premiere, given the experimental nature of my pieces. ”In the same letter, he decreed that Galileo was banned from performing because of the revision of the text. The mother Courage may only be performed with Helene Weigel in the lead role.

Due to the dissatisfaction with the reception of the world premiere in Zurich, Brecht made some text changes for the planned Berlin performance. He made the figure of the mother Courage more negative. Eilif's departure to join the soldiers in the first scene is now less due to his own motives, but is caused by her mother's business interests. In the 5th scene she no longer gives out bandages voluntarily, but only under duress. In the 7th scene she still curses the war, but then defends it as a business like others. Brecht wanted to distance himself from Niobe interpretations, which saw in the mother courage only the suffering of the mother who survived her children:

“We have to change the first scene of the» Courage «, since it is already laid out here what allowed the viewers to let themselves be shaken mainly by the durability and carrying capacity of the tortured creature (the eternal mother animal) - where it was but that is not so far away. Courage now loses her first son because she gets caught up in a small business, and only then comes her pity for the superstitious sergeant, who is a softness that comes from business and that she cannot afford. That is a definite improvement. It is suggested by the young Kuckhahn. "

Brecht's return to Berlin - rehearsals

On October 22, 1948, Brecht had been back in Berlin with Helene Weigel and lived in the remains of the Hotel Adlon . Through the artistic director Wolfgang Langhoff , who had played Eilif in Zurich, he made contact with the Deutsches Theater , where Paul Dessau also had a study. Langhoff offered him to stage in his house, also with his own ensemble. In November 1948, Erich Engel came to Berlin, whom Brecht valued as one of the founders of epic theater alongside Piscator. Engel immediately began, in collaboration with Brecht, with the production of Mother Courage at the Deutsches Theater.

With the exception of Helene Weigel and Werner Hinz in the role of field preacher and Paul Bildt as cook, the ensemble with which Brecht and Engel worked consisted of young actors such as Angelika Hurwicz or Ernst Kahler , who had started their careers during the Nazi era . Brecht registered a “strange aura of harmlessness” in them, but worked with them without reservation. Brecht conveyed his theater concept to the ensemble not through theoretical lectures, but through practical work.

“Only in the eleventh scene do I turn on epic tasting for ten minutes. Gerda Müller and Dunskus, as farmers, decide that they cannot do anything against the Catholics. I have them add "said the man", "said the woman". Suddenly the scene became clear and Müller discovered a realistic attitude. "

Premiere at the Deutsches Theater in 1949

Brecht's drama affected the sense of time of the little people who had learned in the ruined city of Berlin that the war would bring them nothing.

“When the Courage car rolled onto the German stage in 1949, the play explained the immense devastation caused by the Hitler War. The ragged clothes on the stage were like the ragged clothes in the auditorium. [...] Whoever came came out of ruins and went back into ruins. "

The audience could identify with the social position and the war experience of the mother Courage, her actions and failure did not allow any identification.

“In this respect, the piece made completely new demands on the audience. The stage design also polemicized against viewing habits that the theater had cultivated during fascism [...]. The car of courage rolled over the almost empty stage in front of the whitewashed circular horizon. Instead of the large curtain, the fluttering half-curtain. An emblem lowered from the Schnürboden announced the interruption of the action with songs. But the audience did not feel shocked by the new type of representation, but rather moved, as the stage was about very elementary questions, about the human efforts that have to be made in order to survive. "

Before the public premiere, Brecht presented the piece in a closed performance for trade unions. Manfred Wekwerth, at that time still a newcomer to Brecht's environment, comments on Brecht's efforts to attract the proletarian audience: Even before the premiere, “he insisted on doing a pre-performance in front of factory workers. It actually took place, which very few people know. Brecht was interested in the opinion of these people. He spoke to them after the performance. During the unfamiliar performance, the workers had many questions, criticisms, and there was also sharp rejection and incomprehension. Brecht answered everything with great patience. There are notes from him about this (“Conversation with a young viewer 1948”). That was the audience for which Brecht wrote or wanted to write with preference. "

The premiere took place on January 11, 1949. Until then, interest in Brecht's entry into the Berlin theater scene was restrained and limited to a few theater experts. The great success of the piece changed this abruptly. Helene Weigel played a key role in this, and her portrayal of Mother Courage was applauded by the press and the public. The legendary covered wagon from this production and Helene Weigel's costumes are on display in the Brecht-Weigel-Haus in Buckow .

Reception and effect

Brecht's play was highly controversial from the start, both in the West and in the East. His conception did not correspond to the demand of socialist realism for proletarian hero figures and positive messages. But even in the West, Brecht's socially critical message was not well received.

The discussions about a play, abstract from today's perspective, were extremely explosive in the Soviet occupation zone in the Stalin era. It wasn't just about performance opportunities and travel permits. An official rejection of the form could have had far-reaching personal consequences for everyone involved.

The daily press of the SBZ initially responded positively, in some cases enthusiastically, to the Berlin premiere. Paul Rülla wrote in the Berliner Zeitung on January 13, 1949 that Brecht's drama aimed at the “myth of the German war”, which idealized the Thirty Years War as a religious war. Brecht's play shows "the 'peoples' in the maelstrom of a war of domination and power interests in which, whether victory or defeat, the 'common' man has no part, no part but general misery."

Brecht's drama - according to Rülla - was also successful in form, showing "a new simplicity, a new compactness and size". He expressly praises the epic form, "which expresses the truth in a nutshell". He praises the performers and the unity of the ensemble. “A triumph of the performance in its essential intentions. [...] Brecht's work in Berlin [...] must not remain an episode. "

Nevertheless, there was also criticism: Sabine Kebir points out that some GDR critics were of the opinion “that the piece does not meet the requirements of the socialist realism prevailing in the Soviet Union. They complained that the courage did not come to a conclusion. It was no coincidence that Fritz Erpenbeck , Friedrich Wolf and Alfred Kurella disapproved of the central point of Brecht's aesthetic - the message should not come off the stage in an authoritarian manner. They had returned from exile in the Soviet Union and resumed the formalism dispute of the 1930s on German soil. "

Fritz Erpenbeck massively attacked Brecht's concept of epic theater in the “ Weltbühne ” in 1949. The success of the Courage premiere is based not only on the acting performance, but above all on classic dramatic elements that break through the narrative, especially in the form of the drama between "player and opponent", as the "victory of the 'dramatic' theater over the 'epic'" , in contrast to Kattrin and Courage.

In the Neue Zeit of January 13, 1949, Hans Wilfert criticized Brecht's stylistic lag, lack of realism, “lack of colorful abundance” of the stage design and lack of progressive impulses. “We tried out many variations of this Brechtian 'style' before 1933; we do not need to repeat the experiment. Brecht stopped by him, we didn't. "

The criticism of the performance and of Brecht's theater concept culminated in a controversy between Fritz Erpenbeck , cultural functionary and editor-in-chief of the magazines Theater der Zeit and Theaterdienst 1946 to 1958 and critic of the Brechtian theater concept, and on the other hand Wolfgang Harich , who defended Brecht. In various magazines, Erpenbeck and his colleagues criticized Brecht's theater concept in barely clauses as falling behind the development of socialist realism. Courage stands for “surrender to capitalism”.

In March 1949, the Soviet military administration in Germany, SMAD, took a stand on the controversy surrounding Brecht in the official Daily Review . Despite reservations about Erpenbeck's emotional criticism, SMAD confirmed the critics. Karl-Heinz Ludwig summarizes the position as follows:

“The cat was out of the bag. Brecht was accused of wrong worldview. His wrong concept of realism follows from it. Brecht's epic theater could therefore not be considered socialist realism. His efforts are nothing more than an attempt in the 20th century to stick to the long outdated principles of Goethe, Schiller and Hegel. "

Despite the position taken by SMAD, the controversy continued, for example in a discussion between Harich and Erpenbeck at the invitation of the Berlin University Group in the Kulturbund. There was no real turning away from Brecht. Edgar Hein analyzes: “The dispute with Brecht was, however, precarious for the SED . The renowned author was ultimately a gain in prestige for their system. In spite of all reservations, his theater experiments were not only tolerated, but encouraged by the state. Soon Brecht even got his own theater [...]. "

According to John Fuegi, Brecht is said to have sympathized with Wladimir Semjonowitsch Semjonow , the political advisor to the Soviet military administration and later ambassador of the USSR to the GDR, and thus enjoyed his support, who valued the Courage performance. “After Semyonov had seen the performance twice, he took Brecht aside and said: 'Comrade Brecht, you must ask for anything you want. Obviously you have very little money. '”Fuegi suspects that this impression was created by the deliberately economical equipment. Fuegi rates Erpenbeck's continued criticism of Brecht as an aggressive political attack. Erpenbeck's insinuation that Brecht was 'on the way to an alien decadence ' followed the style of the Moscow show trials . “Denunciatory language of exactly this kind was equivalent to a death sentence in the Soviet Union in the 1930s.” Fuegi emphasizes Wolfgang Harich's courage to stand fully behind Brecht in this situation.

Even Eric Bentley , Brecht translator into English and representatives Brecht in the US, portrays situations and processes that illustrate the pressure on the cultural sector in the Soviet occupation zone and the GDR. Helene Weigel asked the first actors of Koch and Feldprediger - without naming Paul Bildt and Werner Hinz - why they went to the West. One of the actors replied that it was not very pleasant to see how people in the East - sometimes colleagues - disappear one day and are never to be seen again. Die Weigel replied: “Where there is planing, there are shavings.” However, unlike later his heirs, Brecht himself continued to work with Bentley, although Bentley did not hide his distance from Soviet-style communism.

Courage was staged by the Deutsches Theater until July 1951, and with the premiere on September 11, 1951, the play changed to a new production in the repertoire of the Berliner Ensemble . The Berliner Ensemble performed it 405 times until April 1961. On March 19, 1954, after long efforts, the Berliner Ensemble moved into its own house, the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm .

But Brecht also made a breakthrough in the West. Guest performances with the Courage production in Paris 1954 and London 1956 help the ensemble to gain international recognition. The French theoretician Roland Barthes speaks of a "révolution brechtienne" because of the guest performance in Paris, of an enormous effect on the French theater.

“The central concern of Mother Courage is the radical unproductivity of war, its mercantile causes. The problem is by no means how to regain the viewer's intellectual or sentimental approval of this truism; it does not consist of leading him with pleasure into a romantically colored suffering of fate, but, on the contrary, of carrying this fate out of the audience onto the stage, fixing it there and lending it the distance of a prepared object, to demystify it and finally deliver it to the public. In Mother Courage , doom is on the stage, freedom is in the hall, and the role of dramaturgy is to separate one from the other. Mother Courage is caught up in the fatality that she believes the war is inevitable, necessary for her business, for her life, she does not even question it. But that is put in front of and before and happens outside of us. And the moment we are given this distance, we see, we know that the war is not doom: we do not know it through a fortune-telling or a demonstration, but through a deep, physical evidence that comes from the confrontation of the The viewer arises with what is seen and in which the constitutive function of the theater lies. "

To this day, the mother Courage is played internationally. In 2008 Claus Peymann made a guest appearance with the piece in Tehran and was celebrated by the audience.

“Brecht is one of the most popular German writers in Iran. At the premiere of Peymann's production of his play "Mother Courage and Her Children" there was applause for the Berliner Ensemble for minutes in Tehran. "

The courage model from 1949

After the great success of the Berlin performance, Brecht had a “model book” drawn up in the spring of 1949, which was intended to make the Brecht Engel production a binding model for all further performances by Mother Courage. Photos by Ruth Berlau and Hainer Hill document each picture very extensively down to the representational details. Director's notes for the individual scenes, probably made by assistant director Heinz Kuckhahn , with Brecht's corrections, complete the picture. On behalf of Suhrkamp Verlag , Andreas Wolff informed the Städtische Bühnen in Freiburg im Breisgau on July 13, 1949:

“The author has very specific ideas about the staging of his works and does not want the directors to interpret them individually. A sample performance is the performance in the Deutsches Theater Berlin, which was created with the cooperation of the poet. A special director's score is in preparation. As long as this is not available, it is Mr. Brecht's wish that Helene Weigel , the actress of Courage in Berlin, should appear at the beginning of the performance on one evening if possible and convey an idea of the intentions. Ms. Weigel is also ready to take part in the last rehearsals and to work with them. "

As Werner Hecht notes, out of distrust of the directors in Hitler's Germany, Brecht did not issue a performance permit until October 1949; a performance in Dortmund that did not adhere to the model was banned in autumn 1949 shortly before the premiere. Brecht's skepticism becomes more understandable when one takes into account that the Dortmund theater director Peter Hoenselelaers was formerly a staunch National Socialist and “general manager” of the Dortmund theater from 1937–1944.

The Wuppertaler Bühnen are the first to stage Mother Courage based on the model book. The Wuppertal director Erich-Alexander Winds receives photos and hectographed stage directions and the recommendation to be instructed by Brecht's colleague Ruth Berlau . During the rehearsals in September 1949, the model process was already heavily criticized by the press. For example, the headline of the criticism in the Rheinische Post Düsseldorf on September 16, 1949: “Author commands - we follow! Living theater organs at the service of the template. ”The premiere will take place on October 1st.

In the fall of 1950, Brecht tried out the model book himself with a production at the Münchner Kammerspiele , whose director from 1945 to 1947 was Erich Engel . He further develops the model and includes changes and further developments in the documentation. Brecht “staged the 'Courage' in Munich based on his Berlin model. He checked the pictures in the model book if it was a question of groupings and, above all, of distances. He looked for the pictorial and the beautiful, but never slavishly following his own model. He let the new performance come into being: perhaps there was a new solution; but the new solution had to be at least as high as the old, already tried and tested model solution. ”Therese Giehse plays the main role, the premiere is on October 8, 1950.

Parts of the courage model were published in 1952 in an anthology on the work of the Berliner Ensemble in the GDR. The part on the courage model, supplemented by a photo collection, is sent to theaters that are planning a performance. Since around 1954, Brecht has been moving away from the model obligation, only obliging the performing theaters to purchase the material. With Ruth Berlau and Peter Palitzsch, Brecht developed a version of the model book for publication in Henschel Verlag in 1955/56 . He selects photos and notes for the performances and revises them. The book does not appear until posthumously in 1958.

Barbara Brecht-Schall had the rights to Brecht's estate from three children of Bertolt Brecht from 2010 until her death in 2015; her siblings had already died. Die Welt writes: "According to her own admission, she is interested in the faithfulness of the works and adherence to the tendency of the pieces, she does not have any influence on the artistic design of the productions." Protest against the influence of the Brecht heiress. “Helene Weigel was recognized and respected by the entire virtual Brecht family as a leader. Nobody objected to the staging instructions of the master and the great widow. Brecht's son Stefan, who looks after the Anglo-Saxon market from New York, was left out. But when Barbara took over the home front, the boiling point began. ”As early as 1971, the SED party leadership urged them to hand over the manuscripts they had kept and to transfer them to the state. She had courage and refused. But there was also some pressure on the Brecht daughter in the West: “As a 'threepenny heir', Barbara Schall was dragged in the dirt, especially by left-wing intellectuals. In 1981 ZEIT critic Benjamin Henrichs shouted 'Disinherited the heirs' and was able to quote the theater makers Peymann, Flimm and Steckel who wanted the same thing, and of course, like Kurt Hager, in the interests of the 'people'. ”Not until 2026, 70 Years after Brecht's death, the rights to the pieces expire.

Cold War - boycott and blockade breaker performance in the Vienna Volkstheater

During the Cold War , Brecht's plays were boycotted as communist propaganda in Vienna between 1953 and 1963 on the initiative of the theater critics Hans Weigel and Friedrich Torberg and the Burgtheater director Ernst Haeussermann . A performance of Brecht's Mother Courage in the Graz Opera House on May 30, 1958 was the occasion for a publication by thirteen Brecht critics under the title "Should one play Brecht in the West?"

At the end of the more than ten-year Brecht boycott in Vienna, the Vienna Volkstheater performed the play in a "Blockadebrecher" premiere on February 23, 1963 under the direction of Gustav Manker with Dorothea Neff (who was awarded the Kainz Medal for her performance ) in the title role, Fritz Muliar as cook, Ulrich Wildgruber as Schweizererkas, Ernst Meister as field preacher, Hilde Sochor as Yvette and Kurt Sowinetz as recruiter. The performance had previously been postponed several times, most recently because of the construction of the Berlin Wall .

In the Federal Republic of Germany, too, there were several boycotts of Brecht plays at theaters during the Cold War . Stephan Buchloh mentions three political reasons that led to theaters canceling or removing Brecht's plays without government coercion: “after the uprising in the GDR that was suppressed by the military on June 17, 1953, after the Hungarian uprising was put down by Soviet troops in autumn 1956 and after the Wall was built on August 13, 1961. “Mother Courage was affected in one case by the few government agencies taking measures against Brecht performances. “On January 10, 1962, the Lord Mayor of Baden-Baden , Ernst Schlapper (CDU), banned a performance of this work by Bertolt Brecht. The Baden-Baden Theater originally wanted to bring out the play under the direction of Eberhard Johows on January 28th of that year. "

The official instructions did not come formally from the mayor's office, but from the spa and spa administration, which ran the theater and which the mayor was in charge of. For the CDU, city councilor von Glasenapp justified the ban in the municipal council by addressing Brecht's solidarity with the SED and Walter Ulbricht after June 17, 1953. It was expressly denied that it was about the artistic quality of the drama. A federal constitutional judge and several writers living in Baden-Baden protested against the ban. The Strasbourg Municipal Theater and the Colmar and Mulhouse theaters then invited the people of Baden-Baden to stage Courage as a guest performance there, whereupon Schlapper extended his ban accordingly on February 1, 1962. On February 5, Schlapper lifted the ban on guest performances abroad, so that the premiere could take place in Strasbourg on March 20. The Courage was later allowed to be shown in Baden-Baden after the Suhrkampverlag threatened to claim recourse for breach of contract for the agreed performance.

Settings

Almost all of the songs in the piece were already set to music by various composers from various contexts. For the "Mother Courage" the lyrics had to be further developed and a new overall musical concept developed. In 1940 the Finnish composer Simon Parmet created a first version that is believed to have been lost. Paul Burkhard composed the music for the Zurich premiere and conducted it himself. In 1946 Paul Dessau worked on a third composition for the piece in collaboration with Brecht. The sound should give the impression "as if you were hearing well-known tunes in a new form ...". Dessau's music was controversial in the GDR from the start, but Brecht consistently stuck to Dessau's performance rights to Mother Courage, even with every production in the West.

Film adaptations

Early on, Brecht looked for ways to transfer his concept of epic theater to film. Various scripts and technical ideas emerge. The first drafts meet the GDR cultural policy's need for positive heroes. A young miller develops perspectives, at the end of the film a peasant uprising is to be shown.

In 1950 Emil Burri becomes the new scriptwriter, Wolfgang Staudte is to direct. Until May 1954 there were always new conflicts, then a contract was signed. In addition to Helene Weigel in the role of mother, the French stars Simone Signoret and Bernard Blier are engaged. Filming began in 1955. Conflicts quickly arise between the successful director Staudte and Brecht. Despite personal intervention by SED leader Walter Ulbricht , Brecht stuck to his point of view that the film should stylistically follow the Berlin production. The project failed after some parts of the film had already been shot.

On October 10, 1957, the German TV broadcaster DFF broadcast a direct broadcast of the model production by Brecht and Erich Engel from the Berliner Ensemble. The 175 minute long transmission is directed by Peter Hagen .

It was not until 1959, after Brecht's death, that Manfred Wekwerth and Peter Palitzsch realized the DEFA film as a documentation of the theater production. They used various techniques to film Brechtian alienation effects : hard light, chemical changes in the film, blinds, calm cameras, superimposed images and comments, double scenes, economical equipment.

On February 10, 1961, the film opened in 15 cinemas in the GDR and then quickly disappeared in suburban cinemas. Whether this was due to a lack of success or politically is a matter of dispute. The official GDR press gave moderate praise.

analysis

Historical drama from the point of view of the 'little people'

The subtitle of the drama “A Chronicle from the Thirty Years' War” is reminiscent of classical subjects, such as Shakespeare's royal dramas or Schiller's “ Wallenstein ”. Brecht changes perspective and describes the events from the point of view of the common people. Jan Knopf begins his analysis of the drama with this change of point of view from the perpetrators to the victims:

“Brecht turns the classic history of tradition, which takes place among military leaders, princes, kings (and their ladies) around to portray the fate of 'little people': history and its time are no longer measured against the world historical individuals, they are the masses who set the historical data . "

The “plebeian gaze” of the drama does not, however, turn ordinary people into actors in history. They remained “victims of the great story”, “merely reacting”. The interpretation of the events changes, but the courage is not able to change the situation in a creative way. Nevertheless, the new perspective opens up opportunities for change. The interpretation of the Thirty Years' War as a great religious war is exposed - according to Jan Knopf - as a "propagandistic phrase":

“Brecht shows that the contradictions lie within the states and the parties, that those who are below bear all the burdens and consequences of the external disputes: so that for them victories and defeats always mean sacrifices. [...] For Brecht, the Thirty Years' War is not a war of faith: it is a civil war [...] "

Ingo Breuer points out that Friedrich Schiller criticized the men's perspective in his story of the Thirty Years' War:

“The regents fought for self-defense or for enlargement; the enthusiasm for religion attracted their armies and opened the treasures of their people to them. The great crowd, where the hope of prey did not lure him under their banners, believed that they were shedding their blood for the truth by splattering it for the benefit of their prince. "

Brecht's drama thematizes the criticism of historiography from a rulership perspective using the example of the death of Tilly , the military leader of the Catholic League in the Thirty Years' War.

- The field preacher : “Now you are burying the field captain. This is a historic moment. "

Mother Courage : “It is a historic moment for me that you hit my daughter in the eye. It's already half broken, she can't get a husband anymore […] I don't see the Swiss cheese anymore, and God knows where the Eilif is. The war is said to be cursed. "

The courage immediately revokes this brief moment of knowledge by doing it on stage. At the same time as her only curse on the war, she inspects the new goods, which Kattrin acquired in defense and whose value depends on the progress of the war. Immediately afterwards, at the beginning of the 7th scene, she sings about the war "as a good breadwinner".

What remains is the sobering view of the great story. Ingo Breuer comments on this as follows: “This statement does not change the behavior of Courage, but it points to the historiography of the Thirty Years 'War: The death of Field Captain Tilly went down in the history books as a turning point in the Thirty Years' War, but hardly the suffering of the simple ones People […]"

From the perspective of the common people, Brecht does not only criticize the concept of historiography that puts rulers, battles and other major events in the foreground. The drama also demonstrates the brutal ruthlessness of war, especially in the fate and deeds of the Children of Courage. Kattrin loses her voice when soldiers attacked her as a little girl, she is constantly threatened with rape, she is later attacked and disfigured and finally shot for a selfless act. Schweizererkas is tortured and executed. In this cruel environment, Eilif is both perpetrator and victim. He robbed and murders peasants, first as a war hero and in a moment of peace with the same deeds as a criminal. He will be held accountable, not his captain. Throughout the entire play, the family is threatened by fighting, assaults and hunger and despite the willingness to be ruthless, deceitful and the shrewdness of courage, they visibly deteriorate and do not survive.

But the drama also shows the growing devastation caused by the ongoing war outside the family. In the titular section of the 9th scene it says that half of Germany's inhabitants have already been wiped out. Destruction and hopelessness become more and more drastic. Hunger is everywhere.

- Mother Courage : "In the Pomeranian, the villagers are said to have eaten the younger children, and nuns caught robbery."

“This is the story of war as told by 'Mother Courage and Her Children'. It is a story of cruelty, barbarism and bondage, of crimes against humanity, committed with the aim that one ruler can take something from another. It is the story Hobbes tells in his classic description of war, where no benefit arises from human effort, but all live in constant fear and danger of violent death, and human life is lonely, poor, dirty, brutal and brief . "

Courage's comments on the opposing perspective of masters and servants on events are provocative. In his courage model, Brecht points out that the regimental clerk carefully registers what she has said in order to prosecute her if necessary. She hides her provocative views behind ironic praise:

- Mother Courage : “I feel sorry for such a field captain or emperor, maybe he thought he would do something else and what people are talking about in future times, and get a statue, for example conquering the world, that's a big goal for a field captain, he doesn't know any better. In short, he works hard, and then it fails because of the common people, which might want a mug of beer and a bit of company, nothing higher. "

The Berlin production emphasized the effect of the ironic-subversive speech of courage to the death of Tilly by making the pissing scribe stand up to observe the courage more closely. "He sits down disappointed when Courage has spoken in such a way that nothing can be proven."

Baroque topos "upside down world"

Right at the beginning of the play, Brecht has the sergeant say: "Peace, that's just sloppiness, only war creates order." Here Brecht ties in with the baroque topos of the upside-down world, as found in Grimmelshausen, among others. Ingo Breuer points out that Grimmelshausen is “the epoch-typical means of inversion, ie rather a look 'downwards'” and provocatively asks whether this diagnosis does not also apply to Brecht.

The reversal of all values and norms through the war appears in various places in the play. In the second scene, Eilif is awarded a “golden bracelets” by the field captain because he outsmarted a majority of farmers, cut them down and stole 20 oxen from them. When he robbed a farmer and killed his wife during a brief period of peace, he was sentenced to death and executed. This reversal of the rules remains incomprehensible to all.

- Eilif : "I didn't do anything else than before."

- The cook : "But in peace." [...]

- The field preacher : "In the war they honored him for this, he sat on the right of the field captain."

When the mute Kattrin risked her life with her desperate drumming at the end of the piece in order to save the inhabitants of the city of Halle , farmers who fear the consequences accuse her: “Have no pity? Have no heart at all? "

The upside-down world of war also induces the characters to make meaningful linguistic mistakes . So the courage in the 8th scene is appalled, “that peace has broken out”. By inadvertently replacing a word in a phrase with the opposite, courage makes it clear what it actually thinks of peace - for them it is nothing more than a damaging natural event, a calamity, like war for other people: "You meet me in Bad luck. I'm ruined. "(Scene 8)

Positive qualities such as courage , cleverness , loyalty , enthusiasm or compassion are given a completely new status in war. What helps one in peacetime fails completely in times of war. Virtues can no longer be relied on. Brecht compared this phenomenon with the fields of the new physics, in which the bodies experience strange deviations : War has the same effect on virtues that suddenly can no longer be used in a calculating way. The virtues of the little people are only there to make up for the failures of the great:

- Mother Courage : "In a good country you don't need any virtues, everyone can be ordinary, mediocre and cowards if you like." (Scene 2)

This corresponds completely to the principle of life of courage: stay inconspicuous, stay out of everything - and thereby survive. Your skepticism about virtue is justified, because the further course of the plot shows that the positive character sides of your children all cause their downfall: "It is the fault of those who instigate war, they turn the bottom of the people on top," says the field preacher one point (scene 6). The question is whether he's making it a little too easy for himself by excluding the common guilt of the commonplace in the general chaos from the outset.

Faith and War of Faith

One thrust of the play is the criticism of religion, the exposure of the material and power interests behind the facade of the religious war. This criticism is conveyed in part by the contradicting figure of the field preacher, but also by the subversive speeches of Courage and the cook. One topic is the hypocritical speech of the church representatives about renouncing material and erotic desires. This is unmasked z. B. through the field preacher's sexual interest in Kattrin and in courage and his greed for good food and drink. His criticism of the courage that she lives from war contains a twofold contradiction. At the beginning of the play he is a boarder for the military as a field preacher, later he lives from the war gains of courage himself.

Criticism of the warlike "values"

Terms such as “honor”, “heroism” and “loyalty”, especially in the form shaped by the Nazi dictatorship, are anti-virtues for Brecht.

Fowler uses Goebbels' quotes to show the great importance of the concept of honor for the Nazi ideology: "For us National Socialists, however, the question of money is preceded by honor." And shows that the term has negative connotations for Brecht throughout his work. In the drama Mother Courage, the concept of honor initially appears as a demand on the farmers who have been duped by the advertiser to submit to their fate. In scene 3, the courage shows the worthlessness of the concept of honor for the common people:

- Mother Courage : “There are even cases where the defeat for the company is actually a gain for them. Honor is lost, but nothing else. "

Kattrin's reaction to the ensign's word of honor to spare the courage if she stops drumming shows that she has seen through the worthlessness of the concept of honor in war: she “drums harder”.

Another virtue of war that drama targets is heroism. "Unhappy the country that needs heroes," Brecht had Galileo respond to the accusation of cowardice before the Inquisition Court. Courage argues in the same way: whoever needs brave soldiers is a bad field captain.

- Mother Courage : “If he can make a good campaign plan, why would he need such brave soldiers? [...] if a field captain or king is really stupid and he leads his people into the Scheißgass, then the people's courage to die, also a virtue. [...] In a good country there is no need for virtues, everyone can be ordinary, mediocre and cowards if you like. "

The "Song of Woman and the Soldier" and Eilif's fate show the consequence of heroism for the soldier: it causes his death. Courage also ironizes Tilly's “heroic death” in battle as a mere accident.

- Mother Courage : “It was fog on the meadows, it was to blame. The field captain called out to a regiment that they should fight bravely and rode back, but in the fog he was wrong in the direction, so that he was forward and he caught a bullet in the middle of the battle. "

The name of the main character itself refers to courage, but even in the first scene the courage indicates that she always acted out of sober monetary interests, never out of heroism.

The figure of Mother Courage

The complexity of the courage figure

Using the example of the samples for the Caucasian Chalk Circle , John Fuegi shows that Brecht systematically emphasized the contradictions of his figures. If the selflessness of the maid Grusha was worked out in a rehearsal, a negative aspect of her personality was the focus of interest in the continuation, always with the aim of “creating a multi-layered person”. According to Brecht, the way to achieve this is "the conscious application of contradiction." In this sense, Kenneth R. Fowler interprets contradiction as an essential feature of the courage figure and rejects one-sided interpretations of courage as a mother or unscrupulous trader. She deserves both labels, the “hyena of the battlefield” and the maternal figure.

In comments, Brecht himself emphasizes the negative sides of the courage figure. “Courage learns nothing,” Brecht writes over a typescript that he wrote in 1953 for a performance of Courage in Copenhagen. Because learning means changing one's behavior - and that is precisely what courage does not do. She believes at the beginning of the play that the war will bring her profit, and she also believes it at the end of the play when her three children are already dead.

In order to enable an analytical view of courage, Brecht attaches great importance to destroying the audience's sympathy with the means of epic theater . Irritated by the recording of the Zurich premiere as “ Niobe tragedy”, as the tragic fate of the suffering mother, he intensifies the bitter humor and ruthlessness of Mother Courage by changing the text and staging it. Nevertheless, the audience continues to “sympathize” with the courage. It sees in her the suffering mother and the tragic failure of all her efforts.

Ingo Breuer sees in her subversive speeches and her style of language the critical gaze of the common people, as Jaroslav Hašek described it in his figure of the good soldier Schwejk . Schwejk makes authorities look ridiculous with an absurdly exaggerated "fulfillment of duty" and apparently naive, satirical speeches that target the ideals of war and the unreasonableness of its supporters. Courage acts in the same way when it tries to identify itself with a conglomerate of senseless papers or when it analyzes the concept of soldierly virtue. In part, it is precisely the perspective of the trader, the trader who creates the sober view of courage. She recognizes something, which Brecht also admits, namely “the purely mercantile nature of war”. The fact that she does not recognize the danger that threatens her and her children from this sober point of view is her undoing.

The subversive expressions of courage are regularly directed against authorities, "against the rulers and their agents in the military and clergy , on the symbolic level against patriarchy and capitalism." A typical example in drama is the ironization of the goals of the 'great men' and theirs Dependence on the little people. Typical discourse tactics are the confrontation of the "big goals" with the sensual needs of the people as well as the ironic devaluation of the goals.

- Mother Courage : “I feel sorry for such a field captain or emperor, he may have thought he would do something else and what people are talking about in future times, and get a statue, for example he is conquering the world, that is a big goal for a field captain, he doesn't know any better. In short, he struggles, and then it fails because of the common people, which might want a mug of beer and a bit of company, nothing higher. The most beautiful plans have already been put to shame by the pettiness of those where they should be carried out, because the emperors themselves can't do anything, they rely on the support of their soldiers and the people where they are right now, am I right? "

The feminist perspective

Sarah Bryant-Bertail sees Courage as one of the Brechtian female characters who travel endlessly on insecure legs through the social strata of their society - often walking in the literal sense - and who are exiled in a deep sense . From this point of view, the social problems were particularly evident. To this extent, courage is a didactic object. Brecht depicts the path of courage from the seduced and abandoned girl to the increasingly colder businesswoman as a path across the stage, additionally symbolized by the car.

The development of courage is also documented in small, carefully planned details and gestures, for example when she bites a coin to test it. Other props also symbolically represented the various roles of women and their transitions, such as the red high-heeled shoes of the warehouse whore, which Kattrin also tried on.

Fowler sees the protest against the patriarchal principle as a characteristic of Mother Courage. Even the names of their children are determined by the mother and her love affairs, not by the biological fathers. She demonstrates sexual self-determination and clearly demands the freedom to dispose of her body. She confidently chooses her lovers.

- The Sergeant : "Are you kidding me?" [...]

- Mother Courage : "Talk to me decently and don't tell my teenage children that I want to kid you, that's not proper, I have nothing to do with you."

The courage as an unscrupulous trader

"The war is nothing but the business" is the motto of the courage in the 7th scene and she wants to be one of the winners. Fowler therefore considers the crime of courage, her profiteering with the war, to be obvious and can rely on Brecht's interpretation. The figure is drawn as a partner of war and death and thus as a criminal. Fowler points out that she makes her contribution to the war machine consciously, voluntarily, persistently and unapologetically ("deliberate, persistent, and unrepentant"). She acts like this even though she sees through the war propaganda, i.e. not as an innocent victim, not accidentally or fatefully. She also knows the price her behavior demands: the death of her children. In addition, Courage consciously chose to participate in the war:

- Sergeant : "You are from Bamberg in Bavaria, how did you get here?"

- Mother Courage : "I can't wait for the war to come to Bamberg."

Fowler believes inhumanity is an integral part of Mother Courage's trade. Their business was based on the principle that advantages for them and their children could only be achieved through disadvantages for others. Courage knows no pity, not for the peasant people Eilif robbed, not for the wounded in an attack, to whom she refused bandages. The courage song at the beginning of the piece already shows her cynicism towards the soldiers:

- Mother Courage :

- “Guns on empty stomachs

- Your captains, this is not healthy.

- But they are full, have my blessing

- And leads them into the abyss of hell. "

In case of doubt, so Fowler, the courage decides for business and war and against saving their children. Whenever it comes down to saving her children, be distracted by business, negotiate the price for too long, or be absent.

Courage as a mother figure

According to Fowler, the pact with war and death is countered by a maternal side of courage. She tries to save the lives of her children by doing business in the war because there is no alternative for them. The war appears to be eternal because it lasts longer than the time segment shown in the drama. This impression is recorded in the final song of Courage: “The war, it lasts a hundred years.” From their point of view, there is no way to escape the war except an early death.

The inevitability of war is conveyed by the drama by comparing war with the forces of nature. For Fowler, Brecht's Marxism provides further arguments for the fatefulness of the situation of courage: As an expression of certain historical conditions and a representative of the petty-bourgeois class, courage is anything but free. Fowler also sees indications of the fatefulness of the events in the fact that Brecht himself spoke several times of a Niobe tragedy, which refers to the tragic fate of a mother who loses her children.

Fowler also interprets her rejection of all bureaucratic control and her vital, promiscuous sexuality as a commitment to life. The relentless search of courage for business opportunities is also an expression of elementary vitality. In addition, the courage appears as a nursing mother ("nurturer"), for her children as well as for cooks, sergeants and soldiers.

She defends her children again and again, exemplifying the fact that she pulls her knife for Eilif in the first scene to protect the son from the advertiser. There are many examples of courage's concern for her children, but it is most evident in the face of her death. The eloquent courage fell silent in the face of Eilif's departure in the first scene and became monosyllabic in the face of the shooting of the Schweizererkas and the dead Kattrin.

The courage as a representative of the unity of war and business

Courage introduces herself and her family as "business people" and then shows in her performance song that her business is closely linked to war and death. The courage makes a decision by addressing the "captains" with her song, not the common soldiers who are supposed to march to their deaths with good shoes and fed up. As a sutler, she takes on the perspective of the rulers who, like her, wage wars with the intention of making a profit. The Courage is only interested in the soldiers' money and accepts their death cynically:

- Mother Courage :

- “But they are full, have my blessing

- And leads them into the abyss of hell. "

For Fowler, the close interlinking of war and business is documented in the suspicious character and anti-social behavior of Courage. They use the misery of others specifically for their business. Hunger increases the price of your capon, fear in Halle makes your purchase cheaper. In addition, she becomes the ideologist of war (“ideologue for this war”). As in the song of the great surrender, it teaches resignation. She preaches renunciation to her children, while she shows her erotic attachment to the war through her love affairs with soldiers.

For Fowler, one of the essential functions of courage in drama is to represent capitalism as a symbolic figure. From this he draws the conclusion that courage could in no way escape war. Business and war and symbolic figures are so closely linked that they must necessarily be inhuman. This fact requires a critical review of every blame on Courage.

The dialectical unity of courage

For Fowler, the long-lasting anger is the rebellious core of the courage figure. Her character combines opposing aspects, "motherly, nourishing creativity as well as war-friendly, inhuman trade". According to Fowler, the contradictions of the capitalist system and its wars are symbolically captured in the contradiction of courage as the central figure of the drama. In contrast to Kattrin's only short-term revolt, Brecht sees here the self-destructive tendency of the system that represents courage. Nevertheless, with her daughter Kattrin, Courage gave birth to a person who points to future rebellion.

Fowler sees the mother courage as a metaphor for belligerent capitalism. In addition, it personifies the essential contradictions of the capitalist system. This included productivity and destructiveness. They reproduce the ideology of their world by seeking their profit in the exploitation and misery of others. They feed the false hope that the common people could also benefit from the war. At the same time, she was one of the great mother figures of Brecht, who embodied the hope for protection and nourishment in the capitalist world. These aspects are inextricably linked. Her social position as a petty bourgeois enables Brecht to show aspects of both the exploiter and the exploited in the courage figure.

Text intention

Brecht's definition of text intent

Brecht has commented several times on the text's intention of the drama, particularly succinctly and briefly under the title “What a performance of 'Mother Courage and Her Children should mainly show'” in the comments on the courage model:

“That the big business that makes war is not done by the little people. That war, which is a continuation of business by other means, makes human virtues deadly, also for their owners. That no sacrifice is too great to fight war. "

Courage does not recognize this. The viewer should transcend their point of view and realize that there is a historic chance to prevent further wars. The viewer should recognize that “the wars have become avoidable” through “a new, non-warlike social order not based on oppression and exploitation”.

Brecht wants his audience to “instill a real disgust for the war” and in doing so focuses on the development of a socialist social order. Behind the big deals, capitalism is to be recognized and fought as the true cause of war: