mime

The pantomime (from ancient Greek παντόμῑμος pantómīmos , literally "imitating everything") is a form of performing arts . According to modern understanding, it is a matter of physical expression, i.e. facial expressions and gestures , without words. An artist who practices this form of representation is also called pantomime ( the pantomime , female form the pantomime ). Statements by people who cannot or do not want to express themselves with words are referred to as pantomime.

In the course of history, quite different art forms have been understood under this name. Ancient pantomime was a type of dance. However, the preserved sources do not allow it to be exactly reconstructed.

The types of representation known as pantomime in modern times have to do with the fact that up to the 20th century drama was regarded as the highest genre of the performing arts and forms of representation that were not primarily literary, such as dance, artistry or music , tried to portray actions or at least a pictorial or allegorical motto. This gave rise to numerous mixed forms of arts that are not based on the word (and therefore not subject to theater censorship like literary dramas). Music broke away from the claim to depict actions in the 18th century, and dance and artistry followed in the later 19th century. Programmed music, narrative ballets and circus mimes still exist today in their popular forms. Performances by clowns contain elements of pantomime.

As a countermovement to the origin of pantomime from dance and circus artistry, which can still be recognized in silent film (which had a close connection to the variety or vaudeville numbers of its time), a sparse, "autonomous" pantomime, limited to the essentials, has emerged as a modern art form developed. Occasionally this pantomime is combined with other forms of theater, for example in black theater , and more rarely in black light theater .

history

Origins

In ancient Roman theater, pantomime was a kind of virtuoso solo dancer. Roman pantomime was widespread until Christianity banned all forms of public performance. Since the modern era , attempts have been made again and again to justify various forms of theater by referring to antiquity.

With the Commedia dell'arte , the Italian impromptu theater of the Renaissance , a modern form of pantomime emerged from the 16th century , which spread across the western world via the detour of the European metropolis Paris. Although language was used here, not only masks such as the figures of Pagliaccio or Pedrolino (becomes Pierrot ) or Arlecchino (becomes Harlequin ) influenced the later pantomime, but also the repertoire of movements that belonged to these types, including the improvised lazzi .

Associated with the concept of mime the idea of a general intelligibility across language barriers and social boundaries of time. In this sense, the English traveling actors, who toured continental Europe from around 1600 without knowing the languages in the countries they visited, also played a part in their development. They took on influences from the Commedia dell'arte.

18th century

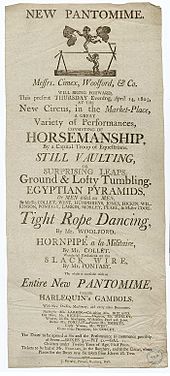

As a popular counterpart to court ballet , a dance form of the Commedia dell'arte, known as pantomime, became common in the 18th century. All over Europe there were dance companies that presented these very musical pieces, often with lots of costume changes and transformations on the stage.

The silent pantomime was created in the Parisian fairground theater because the official Parisian theaters were temporarily able to impose a text ban on them for fear of economic competition from these fashionable venues. The Comédie-Française , which at its core still performed the theatrical repertoire of French classical music and was a theater of the French court , jealously watched over its privilege to the spoken word on the stage. This is how pantomime gained the reputation of being an art of the powerless and uneducated.

Aesthetic ideas

In the aesthetics of the 18th century, in a more sophisticated social sphere, the pantomime had a different function. After the death of the dancing king Louis XIV in 1715, it was supposed to justify the increasing detachment from the French court customs, which instrumentalized dance and theater. It symbolized a movement with no rules of behavior. The liberation from the regular steps of ballroom dancing, from the restrictive corset of opera singing, from the poses and rules of declamation of the tragic actors, all of this was called with preference pantomime, which appeared as a vision of limitless freedom, truth and naturalness and was also based on antiquity let. From Jean-Baptiste Dubos ( Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et la peinture, 1719) to Denis Diderot ( De la poésie dramatique, 1758) to Johann Georg Sulzer ( General Theory of Fine Arts, 1771), there are numerous statements in the direction of that the pantomime leads people to nature.

Johann Jakob Engel summarized some of the century's tendencies in his ideas on facial expressions (1786). One of the guiding principles was the belief that the wordless arts of gestures and facial expressions, in contrast to verbose and manipulative rhetoric, undisguisedly reflect the “inside of the soul”. Then gestures and facial expressions would not be art, but nature, according to the ideas at the time. They would not be feasible, but would involuntarily burst out of the inside of the gifted artist. The linguistic expression, on the other hand, was more likely to be suspected of being deceptive and pretending. These ideas can be seen in the pantomime scenes of August von Kotzebue's hatred and repentance (1789). The theoretical discussion cannot be separated from its social and political environment. The mime at the annual fairs was in vogue precisely because it "came out of the gutter" and was originally underestimated, as is the case with many dances or musical styles to this day.

London and Paris

In England, however, the “ Glorious Revolution ” had already happened in 1688 and popular theatrical art was therefore more advanced than on the continent before the French Revolution in 1789, where it had to struggle with numerous restrictions. The ballet master John Weaver justified dance innovations with his treatise History of the Mimes and Pantomimes (1728), which had a great impact. He is often referred to as the founder of English ballet and English pantomime . In the Parisian fair theater, pantomime was seen as a fight against the privileges of court theaters .

The French dancer and choreographer Jean Georges Noverre relied on Weaver, among others, for his reforms of court dance. He separated stage dance from ballroom dancing through more “natural” movements and created ballet en action. But even he was probably not based on the theory of his time, but on the popular pantomimes of the fairs or the guest English actors like David Garrick .

The emergence of pantomime after the French Revolution has to do with the strict theater censorship, which strongly favored performances without text, i.e. without the danger of political utterances. This is one of the reasons why the term pantomime is associated with a subtle criticism of society.

19th century

Pantomime and popular theater

The pantomime in the so-called Volkstheater was still a counterpart to the courtly ballet in the 19th century and was performed in theaters that were not permitted to perform tragic ballets, such as the theater in the Leopoldstadt Vienna (see Der victorious Cupid , 1814). An important “pantomime master” was Louis Milon at the Parisian Théâtre de l'Ambigu-Comique . From this ballet pantomime comes the so-called " English pantomime ", which had a famous interpreter in Joseph Grimaldi (the inventor of the clown). Theatrical performances also formed the core program of the circuses well into the 20th century .

Pantomime and painting

Diderot had already asserted a connection between painting and pantomime ( Dorval et moi, 1757), and this became a separate art genre in the 19th century. “ Living images ” and attitudes that developed from posing for paintings or photos and that were cultivated by Emma Hamilton or Henriette Hendel-Schütz , for example , were sometimes also called “pantomimes”. The rhetoric teacher François Delsarte researched and taught the "natural" postures, which he considered to be the basis of every linguistic utterance. The Delsarte system was particularly influential around 1900.

Pantomime and sport

Since the beginning of the 19th century, gymnastics had a close connection with the further development of pantomime , which then contained more theatrical elements than it does today. The modern pantomime Jacques Lecoq began as a gymnast and Jean-Gaspard Deburau was a master in stick fighting . In addition, fencing has been one of the skills of an actor since that time: He should be able to represent persons of rank authentically and be able to defend himself in honorary acts. Later it became a "senseless physical exercise", but is still used today in actor training for reasons of physical education.

Parisian Boulevard Theater

The boulevard theaters on Paris' Boulevard du Temple were only allowed to use speaking and singing performers on the stage to a very limited extent, because they violated the privileges of the Paris Opera and the Comédie-Française . The Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin, for example, was repeatedly in a fight with the authorities. The "grotesque dancers", as the comic dancers were called at the time, were able to compete with the leading actors from opera and drama. Charles-François Mazurier in the Porte Saint-Martin or Jean-Baptiste Auriol in the Cirque Olympique were the stars of the stage and the ring.

Deburau on the Boulevard du Temple, on the other hand, is considered to be the inventor of the modern, fine and poetic Parisian pantomime, which received great attention in French Romanticism . He created the figure of the poetic, melancholy Pierrot: He was not allowed to speak on stage because the Théâtre des Funambules did not have a license. The artist Deburau was memorialized in Marcel Carné's film Children of Olympus in the portrayal of Jean-Louis Barrault in 1945 .

The melodrama of that time often contains pantomime leading roles, for example The Dog of Aubry (1814) or The Orphan and the Murderer (1816), Yelva, the Russian Orphan (1828). This principle was transferred to opera in Die Stumme von Portici (1828), in which the mute figure had socially critical explosive power, which was confirmed in the Belgian Revolution of 1830. A mute creature did not seem to be acting, but to be undisguised and natural. The silent role as a sympathetic and helpless figure has survived through to modern film melodrama.

20th century

Popular culture and avant-garde

Artist careers like that of Carl Godlewski show that even after 1900 the boundaries between pantomime, circus acrobatics and dance were fluid, even at the highest level. However, this seemed unsatisfactory to some artists. The pantomime of the 20th century, which goes back to Étienne Decroux (he too was one of the actors in Children of Olympus), is influenced not only by the cabaret of the Music Hall and the acting techniques in silent film, but also by attempts at reforming ballet dance, which begin with François Delsarte (see also the 19th century) and lead to the so-called expressive dance by Emil Jaques-Dalcroze or Rudolf von Laban . Laban's movement experiments on Monte Verità have received wide attention. Thus, until after the First World War, a type of movement theater was formed that was neither ballet nor ballroom dancing.

Decroux and the next generation

Etienne Decroux was apprenticed to Charles Dullin , but he turned away from pantomime and founded his own scheme, which he called the "moving statue" or in French "mime statuaire". With this new means of expression, Decroux wanted to distance himself from previous practices and free the body as a mere material from the burden of fable / narrative and role psychology. The body should become the "sole instrument of scenic design". Paul Pörtner wrote: “The starting point of this new 'mime school' was the liberation of the actor from the naturalistic overload with costume, props and an awareness of the essential means of expression of posture and gesture, of physical mimicry instead of facial expressions ".

Plot and narrative dramaturgies were secondary to the work of Decroux. Decroux disliked the aspect that the gesture was more or less analogous to words. He wrote: "Technically and formally, the actor should be able to present his body only as a work without showing himself in it". In order to actually implement this, Decroux had two further research areas: movement isolation and balance as a technical, formal, gymnastic requirement. Decroux declared "mime pur", which had been largely purified from dance and artistic, to the basic form of pantomime (see also Mime corporel dramatique ) and founded the first pantomime school in Paris in the 1930s. His students included Jean-Louis Barrault , who integrated pantomime into acting, and Marcel Marceau , who more and more perfected it into a solo performance culture in the course of his career.

Decroux's views coincided with the efforts of some theater reformers after the First World War, such as Max Reinhardt , Bertolt Brecht and Meyerhold , who also reduced the drama to a clear physical expression that should not be naturalistic but stylized . New ideas for pantomime came from Asian martial arts .

Artists who started with pantomime and broke new ground

In order to better understand Lecoq and his theories, it is important to find out where he started and who was also dealing with expressions of the body at that time. The two theorists to be consulted here are Marcel Marceau and Etienne Decroux. What is interesting about these two artists is that Lecoq and his ideas are right in the middle between the two men Marceau and Decroux. What they all have in common is that the basis of their work was pantomime.

While Marceau endeavored to create a pure pantomime, Decroux wanted to create a completely new revolutionary form of expression of the body, which clearly wanted to distance itself primarily from pantomime, which is interesting because, like Marceau, Decroux had trained with Dullin. Lecoq, on the other hand, referred to pantomime in his ideas, but led his thoughts further to formal language and natural movements.

Marceau describes in an interview with Herbert Jehring that his first encounter with pantomime came through Charlie Chaplin and that the fascination with this way of communicating would stay with him for a lifetime. Marceau studied at Charles Dullin's school and played in his drama troupe. At the age of 24, after several years of experience in spoken theater, Marceau developed the character of Bip: “I took a striped jersey, white trousers, a hat with a flower - and Bip stood in front of the mirror.” Marceau goes on to describe that he wanted to create a "folk hero" in which everyone could find themselves. About the consistently positive response to his art, he said that “silent language is a deep need” in people.

Marceau introduces the term “Le Mime”; this term describes the “identification of man with nature and the elements”. He is referring to the tradition that has been in use since ancient times; he attributes great expressiveness and significance to facial expressions. The make-up turns the faces into masks, as was the case with the Greeks. He also emphasizes that the artist must have certain body control that should be equal to acrobatic skills. In the course of time he formed numerous style exercises. One of his most famous exercises is "Youth, Maturity, Old Age, Death". He performs these alone on a stage without any props, sometimes in the role of Bip, or accompanied by music.

In Jacques Lecoq's work, elements from both artists, Decroux and Marceau, can be found in his work and his text "the poetic text", which is intended to be the basis of this section. The formal language or “mimodynamic work” deals with the topic of dealing with inanimate objects and their representation. Lecoq said, like Decroux, that the point is not to reproduce the words by mere imitation, but rather to reproduce the essence of the words or the objects, and this without auxiliary means such as props. This puristic aspect can be found in both Marceau and Decroux and thus appears to be a particularly important point in their work. It is also the basis of Lecoq's theory that every movement has a meaning or that a movement must be given meaning. In order to be able to grasp the horizon of meaning of a movement, the individual body parts must be viewed in isolation, similar to the way Decroux described it in his work. In order to be able to correctly convey the meaning of a movement, it is important for Lecoq to note that the body is a pure means of transport and has to be in the background itself. This is where Lecoq differs from Decroux, for whom the dramatic content of a movement appears to be secondary and which places the body in the focus of attention.

In his research on body movements, Lecoq filtered out three natural movements that form the basis of his work with the body: the wave movement, the reverse wave movement and the unfolding. Lecoq writes in his work: "The wave movement is the motor of all physical exertion of the human body." The wave movements have four transitional positions that are interesting in relation to Marceau, because in Lecoq they symbolize four different ages, similar to the one above mentioned style exercise by Marceau. This is how Lecoq names the transitional postures "childhood, the body at its zenith, maturity and old age".

Jaques Lecoq, theater pedagogue, acting teacher and pantomime, developed during his creative time as a practitioner of the pantomime art and with the contact with the working method of Jacques Copeau his further developed to his own basics and techniques for his form of expression of pantomime acting, which he founded on his own School taught and where they are still taught today.

The following statements are based on excerpts from his written text The Poetic Body: The initial work takes place in the training according to Lecoq without text. The focus is on the experiences and experiences of the students, which serve as the basis for the game. These should be illustrated by means of a 'miming body'. If this is achieved, students can use imagination to achieve new dimensions and spaces, which Lecoq calls psychological replay. Lecoq also uses masks to reach other levels in the game.

During the above-mentioned processes, there is an intensive preoccupation with the inner workings, which Lecoq calls the “second journey inside”. He describes that this leads to an “encounter with the materialized life”, which reaches the “common poetic ground”. This consists of “an abstract dimension of spaces, light, colors, materials and sounds”, which is absorbed through sensually perceptible experiences and experiences. According to Lecoq, this space of experience is in the body of every person and is the reason for the motivation to create something (artistically). The goal is therefore not only to be able to perceive life, but also to add something to what is perceptible. He describes that with a color, for example, you can neither see shape nor movement, but the color evokes a certain emotion in you, which leads to movement / movement / being moved.

This state of affairs can be expressed through “mimages”, which Lecoq describes as “gestures that do not belong to the repertoire of real life”. By looking at an object and an emotion that arises during it, everything can be transformed into a movement. However, this should not be confused with a pictorial representation (figuration mimée). The aim is to achieve emotional access and not “theatrical exaggeration”. During the training you learn to project the elements that are inside the body outwards. In their artistic work, the pupils should develop their own movements that come out of their bodies (no fixed symbols, no clichés). The goal is to reach the inside. Poetry, painting and music provide central reference points for this way of working. Elements such as colors, words or sounds are isolated from these arts and transferred to the physical dynamics. Lecoq calls this "mimodynamics".

The technique of movements is the second stage of Lecoq's pedagogy. He analyzes three different aspects in his teaching: firstly the physical and vocal preparation, secondly the dramatic acrobatics and thirdly the analysis of the movements. During the physical preparation, each part of the body should be treated separately from one another in order to be able to analyze the “dramatic content”. Lecoq emphasizes that a movement, a gesture that is used in theater must always be justified. Lecoq refers to three possibilities to justify a movement. On the one hand by hint (belonging to pantomime), action (belonging to Commedia dell'arte) and through the inner state (belonging to drama). In addition, with every movement that the actor exerts, he is in a relation to the spatial environment that evokes feelings inside. The external environment can consequently be absorbed and reflected within. For physical preparation, it is important that the actor should detach himself from role models or from ready-made theater forms when miming. The physical preparation serves to be able to achieve “correct” movements without the body being in the foreground. The body should only serve as a means of transport in art.

Furthermore, Lecoq repeatedly describes that every gesture must be justified. An approximation of the gesture is the mechanical understanding of the process and consequently the extension of the gesture in order to be able to carry it out as much as possible and to experience its limits. Lecoq calls this process "dramatic gymnastics". The dramaturgy of breathing is guided by an "upper breathing pause" by means of associations with images, while breathing is controlled. The voice cannot be isolated from the body. According to Lecoq, voice and gesture have the same effect. Lecoq claims that many of the methods students are taught have nothing to do with acting, and emphasizes the importance of movement, which is stronger than the act itself.

According to Lecoq, dramatic acrobatics generally serve to give the actor greater freedom in acting through acrobatic techniques. He describes them as the first of the natural movements that children, for example, perform and seem useless in themselves. Yet they are casual movements that we learn before any social convention teaches us otherwise. The dramatic acrobatics begin with flips and somersaults, natural movements that we really know from childhood. Lecoq tries to start from scratch to lead the actor back to his original movement. The level of difficulty changes continuously with the exercises, that is, you start with children's exercises until you get to somersaults and window jumps. Lecoq's goal here is to free the actor from gravity. With the acrobatic game, the actor would come up against “the limit of dramatic expression”. Therefore, the training in Lecoq's school runs through the entire training.

Juggling is also part of the training. Here, too, the actor begins to practice with one ball until he eventually manages three and can then dare to approach more difficult objects. Fights follow juggling. This includes slapping Lecoq in the face and even fighting seemingly real fights. Here he mentions "an essential law of the theater: the reaction creates the action". This is how we come to help. This describes "the accompaniment and securing of the acrobatic movements", for example a supporting hand in the back during a somersault, because an actor should not expose himself to the risk of falling.

At Lecoq, the analysis of movements is one of the basics of an actor's body work. The Lecoq actor embarks on a "journey inside". For this purpose, Lecoq trains its students in various activities such as pulling, pushing, running and jumping, through which physical traces are drawn in a sensitive body that draw emotions with them. Body and emotion are thus linked to one another. The actor experiences his own body and recognizes how certain activities feel and to what extent there are opportunities to vary within them and to gain flexibility in the game. So he explains in the subsection "the natural movements of life", which he divides into three natural movements: 1. The wave movement 2. The reverse wave movement 3. The unfolding:

The wave movement, which is also referred to as the expressive mask in relation to the mask play, is the basic pattern of all movement. No matter what movement, be it a fish in the water or a child on all fours, humans move in waves. The floor forms the basis of any wave movement, which then runs through the entire body and finally reaches its point of action. The reverse wave movement, also known as the countermask in relation to the mask play, has the head as its base, but is basically the same movement as that of the wave movement. There is a "dramatic hint" here. The unfolding, also known as the neutral mask in relation to the mask play, is in balance between the wave movement and the reverse wave movement, and arises from the center. The movement begins crouching on the floor, making yourself as small as possible. The movement ends with the actor standing in the "upright cross", so he stretches everything away.

After these basic movements, Lecoq now makes a few modifications in order to expand the range of variations of the learned movements. The basic principles here are: enlargement and reduction in size to practice keeping your balance and thus to experience your spatial limits; Balance and breathing, which represent "the extreme limits of any movement"; Imbalance and locomotion, i.e. avoiding a fall, physically and emotionally. Lecoq always follows the path from the big game to the nuanced, small, psychological game. He also goes into the emergence of posture. For this purpose, Lecoq developed nine postures, which should avoid natural movements, as this makes artistic exaggeration easier. The modifications can also be introduced here, because if you combine any movement with a certain breathing, this can signal a different meaning of the gesture, depending on how you breathe. Lecoq brings in the example of parting: "I stand there and lift an arm to say goodbye to someone." If the person inhales with this gesture, a “positive feeling of farewell” arises.

Samy Molcho again combined pantomime with the means of expression of ballet and Dimitri with those of the clown. The latter connection in particular experienced a new upswing through the fools, clowns and fools movements of the late 1970s and early 1980s, especially through Jango Edwards and his Friends Roadshow from the Netherlands. While Marceau mainly appeared as a solo artist, Ladislav Fialka in Czechoslovakia, Henryk Tomaszewski in Poland and Jean Soubeyran in Germany preferred ensemble work and linked it with dance theater or drama. Arkadi Raikin in the Soviet Union even went so far as to combine them with elements from operetta and cabaret , which made him a well-known satirist and comedian. The group Mummenschanz successfully brought their variant of a pantomime with full-body masks to the Broadway stage in the 1970s .

Basics and technology according to Jean Soubeyran

After the school of Decroux and the literature of his student Jean Soubeyran used here, the pantomime is designed like a lecture that consists of sentences and tries to inspire the audience through the means of tension and relaxation - "the breathing of the mime". These sentences in turn, like the spoken presentation, consist of punctuation marks and parts that must be related to one another in order to be understandable, and have a beginning and an end. The so-called "Tocs" are used to introduce a pantomime sentence or a sentence element or to conclude an action as a "final Toc", whereby the latter can also be audible as a so-called "push" when the heel or the toes appear. Brigitte Soubeyran, who at times also appeared as a mime, defines the toc as follows: “The toc is a point that initiates a new phase within a movement sequence.” In addition, every gesture is reduced to a minimum of movement and every facial expression is reduced to the simplest possible around her thereby making it "clearer".

This design requires a high level of physical training from the mime or the mime. Many gymnastic so-called “separation exercises” are used in order to be able to move each individual part of the body (one could almost say: each muscle) independently of one another and also against one another. In addition, during the training, work is carried out in the areas of “creating time and space”, dealing with fictional objects, depicting emotions and “dramatic improvisation” in individual or group improvisations as well as the so-called “geometric pantomime”.

The starting point of the latter focus, which aims to "keep the body in balance in all positions" and to allow "no inaccuracy in style, no slack in execution", is the "neutral" position, which varies depending on the "school": slightly angled feet that are hip-width apart, the spine completely straight up to the head, arms and shoulders hang loosely and (very important!) the tongue does not stick to the roof of the mouth, but also hangs loosely in the middle of the oral cavity. Decroux called this position the " Eiffel Tower " because it has a physiognomic similarity to it. With the “tree” posture as the starting point, however, the heels touch each other slightly, with the “Japanese” posture the knees are slightly pushed in so that they stand exactly above the feet, the pelvis pushed forward and the palms open forward. Then, using the rhythmic elements of a toc or a so-called "fondu", a flowing and even transition from one position to the next, a wide variety of physical exercises are worked on.

The pantomime thus initially works in two independent areas: that of "body technique" and that of "improvisation". By doing both independently, they approach each other. The more the mime has perfected the physical technique without thinking about it, and the more he has expanded his abilities and possibilities of expression in the area of improvisation exercises, the more these two seemingly contradicting areas combine to form a unity that ultimately becomes a great one Part of the “game” of the mime who has now become an athlète affectif, a “sensitive athlete” (Barrault).

A final, but no less important point for the pantomime is the work with the "mask", which, as everywhere in the theater, film or television, is not to be understood exclusively as a superimposed, plastic one. This has the function of creating a distance between the mimes and the audience. Soubeyran wrote:

“Because the mime loses his human face, he removes and enlarges himself for the audience [...] In the case of people with an uncovered face, the viewer's gaze is always drawn to the image, the body is of secondary importance. The hidden face, on the other hand, is completely integrated into the body, it disappears and thus brings the head to bear. The head is now much more important, it has to replace the face. "

Only perfection in all of these areas makes pantomime an art and distinguishes it from amateur performances. As an example, a hand is never brought to the ear to show that something is being heard, but the head is slowly pushed horizontally (as if on a rail) in the direction of the (supposed) noise without moving the shoulders and “To pull along” or to tighten the facial expression. The “scanning of walls”, which lay people like to bring about, is therefore not a “slap in the air” as is the case with these, but rather an almost “real” scanning of walls by tensing and relaxing the muscles and tendons of the fingers and hands that you almost believe you can see the wall.

Jean Soubeyran wrote:

“Mime is ceaseless creation and, like all creation, a struggle. The object that I want to create imposes its idiosyncrasy on my body. My body, thereby becoming a servant of the object, gives life to it in turn. The body of the mime is subject to the object that he himself creates. "

“If I put my hand on a real wall, then of course there is no need to keep a surface. Due to its inactive matter, the wall naturally dictates my hand's posture, which, passively, does not need to make any effort. In contrast, the mime, together with the fictitious wall, creates not only the surface of the wall, but also its passive power. The muscles of the wrists and hands do a hard job ... "

Current situation

Despite the efforts to create a “pure” pantomime, the term is still very far-reaching today and the transition to dance theater or performance is fluid. Also in street theater , in discotheques or in the field of youth culture, there are diverse performances that are more or less “pantomime”, for example breakdance , where even elements from the Marceau school have been adopted. The street artists who often appear in pedestrian zones and perform " living statues " occasionally use pantomimic elements such as the reduction to essential movements (see also under Basics and Technology).

The demarcation of classic pantomime from popular entertainment, as demonstrated by artists from Decroux to Marceau, has also isolated pantomime in a certain way, just as other elitist currents in theater and music that emerged from the avant-garde at the beginning of the 20th . Century emerged. A voluntary renunciation of spoken language is less attractive than an enforced one, which once resulted from censorship regulations, from the lack of sound in silent films or from the almost impenetrable volume of fairs and music events. While the famous Marceau managed to fill huge halls, many contemporary pantomimes find fewer and fewer opportunities to perform. It seems as if the "silent art" ( L'Art du silence, Marceau) performed in silence is too quiet.

Other previously not mentioned famous pantomimes

- Walter Samuel Bartussek

- Kurt Eisenblätter

- Eberhard Kube , the most famous pantomime of the GDR

- Oleg Popov (also clown )

- Milan Sládek (also director)

- Pan Tau (played by actor Otto Šimánek )

- Clement de Wroblewsky (Clown Clemil)

Contemporary pantomimes

- Bodecker & Neander

- Stanislaw Brzozowski

- Damir Dantes

- Mehmet Fıstık

- Anke Gerber

- Ulrich Gottlieb

- Ingrid Irrlicht

- JOMI

- Carlos Martínez

- Irshad Panjatan

- René Quellet , solo and as partner of Franz Hohler

- Massimo Rocchi

- Andrew Vanoni

- Vahram Zaryan

- Pablo Zibes

"Pantomime" as a parlor game

See also

literature

- Walter Bartussek: pantomime and performing game. Grünewald, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-7867-1427-4 .

- RJ Broadbent: A History of Pantomime. First edition 1901, IndyPublish, 2005, ISBN 1-4142-4923-3 . Online in Project Gutenberg.

- Kay Hamblin: Mime. Ahorn, Soyen 1973, ISBN 3-88403-005-1 .

- Janina Hera: The enchanted palace. From the history of pantomime. Henschel, Berlin 1981

- Annette B. Lust: From the Greek Mimes to Marcel Marceau and Beyond. Mimes, Actors, Pierrots and Clowns. A Chronicle of the Many Visages of Mime in the Theater. Foreword by Marcel Marceau. The Scarecrow Press, London 2000, ISBN 0-8108-4593-8 .

- Marcel Marceau, Herbert Ihering: The world art of pantomime. First edition 1956, dtv, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-423-61870-1 .

- Stephanie Schroedter: dance - pantomime - dance pantomime. Interactions and delimitations of the arts in the mirror of dance aesthetics. In: Sibylle Dahms ua (Ed.): Meyerbeer's stage in the structure of the arts. Ricordi, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-931788-13-X , pp. 66-81.

- Stephanie Schroedter: Pantomime. In: Gert Ueding (Hrsg.): Historical dictionary of rhetoric . WBG 1992 ff., Vol. 10, Darmstadt 2011, Col. 798-806

- Jean Soubeyran: The wordless language. A new edition of the pantomime textbook. Friedrich, Velber near Hanover 1963, and Orell Füssli, Zurich / Schwäbisch Hall 1984, ISBN 3-280-01549-9 .

- Hans Jürgen Zwiefka: pantomime, expression, movement. 3rd edition, Edition Aragon, Moers 1997, ISBN 3-89535-401-5 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Marcel Marceau, Herbert Jhering: world art of pantomime. Aufbau Verlag, Berlin 1956. p. 29

- ↑ Franz Cramer: The impossible body. Etienne Decroux and the search for the theatrical body. Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 2001. p. 5

- ↑ Franz Cramer: The impossible body. Etienne Decroux and the search for the theatrical body. Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 2001. p. 12

- ^ Eva Wisten: Marcel Marceau. Henschelverlag, Berlin 1967. p. 7

- ↑ Franz Cramer: The impossible body. Etienne Decroux and the search for the theatrical body. Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 2001. p. 12

- ↑ Marcel Marceau, Herbert Jhering: world art of pantomime. Aufbau Verlag, Berlin 1956. p. 12

- ↑ Marcel Marceau, Herbert Jhering: world art of pantomime. Aufbau Verlag, Berlin 1956. p. 25

- ↑ Marcel Marceau, Herbert Jhering: world art of pantomime. Aufbau Verlag, Berlin 1956. p. 34

- ^ Eva Wisten: Marcel Marceau. Henschel Verlag. Berlin 1967. p. 17

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 70

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 95

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 104

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 106

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 107

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 69

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 69

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 69

- ↑ See Lecoq, The poetic body, p. 69.

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 69

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. pp. 69-70

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 70

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 96

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 97

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 97

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 99

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. pp. 100-101.

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 103

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 102

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 102

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 103

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 103

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 103

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 104

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 104

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 104

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 106

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 106

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 108

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. P. 109 ff.

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 110

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 111

- ↑ Jacques Lecoq: The Poetic Body. Alexander Verlag, Berlin 2003. p. 111

- ↑ The first edition from 1963 was used; see under literature. The pagination is identical to that of the new edition.

- ^ Jean Soubeyran: The wordless language. A new edition of the pantomime textbook. Friedrich, Velber near Hanover 1963, and Orell Füssli, Zurich / Schwäbisch Hall 1984, p. 10.

- ↑ Quoted from Jean Soubeyran: The wordless language. A new edition of the pantomime textbook. Friedrich, Velber bei Hannover 1963, and Orell Füssli, Zurich / Schwäbisch Hall 1984, p. 11. For Brigitte Soubeyran, see also the section “ Family Compendium ” in the article on Jean Soubeyran.

- ^ Jean Soubeyran: The wordless language. A new edition of the pantomime textbook. Friedrich, Velber near Hanover 1963, and Orell Füssli, Zurich / Schwäbisch Hall 1984, p. 57.

- ↑ Kay Hamblin; see under literature.

- ^ Jean Soubeyran: The wordless language. A new edition of the pantomime textbook. Friedrich, Velber near Hanover 1963, and Orell Füssli, Zurich / Schwäbisch Hall 1984, p. 20.

- ↑ Quoted from Jean Soubeyran: The wordless language. A new edition of the pantomime textbook. Friedrich, Velber near Hanover 1963, and Orell Füssli, Zurich / Schwäbisch Hall 1984, p. 7.

- ^ Jean Soubeyran: The wordless language. A new edition of the pantomime textbook. Friedrich, Velber near Hanover 1963, and Orell Füssli, Zurich / Schwäbisch Hall 1984, p. 92 f .; Application of the new spelling.

- ^ Jean Soubeyran: The wordless language. A new edition of the pantomime textbook. Friedrich, Velber near Hanover 1963, and Orell Füssli, Zurich / Schwäbisch Hall 1984, p. 15.

- ^ Jean Soubeyran: The wordless language. A new edition of the pantomime textbook. Friedrich, Velber near Hanover 1963, and Orell Füssli, Zurich / Schwäbisch Hall 1984, p. 31.