Literary pantomime

The literary pantomime is a specific literary genre that textualizes the staging of a non-verbal , silent action in pantomime design. As an independent genre that established itself in German-language literature around 1900, literary pantomime was only comprehensively and fundamentally examined and defined in a larger study in 2011.

history

The development of the genre began with the emergence of pantomime as an archetype of theater , in which worship of gods and mythological representations were staged in combination with dance or with the speech or singing of a choir . Becoming popular in Greek and Roman antiquity , the pantomime experienced further heyday through the medieval jugglers and jugglers , then, in the 16th century, especially through the Commedia dell'arte , the Italian impromptu and type comedy, as well as its French variant, the Comédie Italians . In the German-speaking countries, in the 18th century, there was an increasing focus on pantomime as part of an aesthetic theory and a reform of drama ( Gotthold Ephraim Lessing , Johann Georg Sulzer , Johann Jakob Engel ), whereby it was emphasized that the pantomime gesture as a form of representation of emotional , the emotions and the passions is superior to the word. - The pantomime then reached its next high point in the Viennese suburban theaters of the early nineteenth century, where so-called magic pantomimes, which presented fairy tale motifs and supernatural, ghostly events, enjoyed great popularity.

At the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, especially in Vienna, a new interest in pantomime developed, and now the genre of literary pantomime was established by well-known authors such as Hermann Bahr , Richard Beer-Hofmann , Hugo von Hofmannsthal , Felix Salten and Arthur Schnitzler , who wrote works that were explicitly understood as pantomime texts . The fact that literary pantomime was in its heyday in Vienna and that progressive poets representing modern literature (who came together in the circle of Junge Wien ) turned to this art form is due, on the one hand, to the traditional background of the Viennese folk theater and its affinity for commedia dell'arte and to be explained as fairytale-fantastic magic games; On the other hand, however, also essentially with the search of progressive, modern authors for new artistic forms of expression, a search that was founded on a considerable skepticism and profound language crisis, as paradigmatically in Hofmannsthal's famous Chandos letter , published in 1902 , a key text of literary modernity , was expressed. For the authors of Junge Wien , literary pantomime became particularly important as an aesthetic counter-form to naturalism , as a demonstration of an artistically created reality and as a manifestation of an 'art of the soul'. In addition to the increasing criticism of language, the growing interest around 1900 in the psyche of the human being, in mental, unconscious phenomena and processes and in their analytical interpretation gave rise to many pantomime texts during this time. Literary pantomimes such as Richard Beer-Hofmann's Pierrot Hypnotiseur , Arthur Schnitzler's The Veil of Pierrette and The Metamorphoses of Pierrot or Hugo von Hofmannsthal's The Pupil focused on the psychological and psychological phenomena such as personality splitting , hallucinatory phenomena or hypnosis , which were heavily discussed at the time these works were created of the silent game. The imagery and symbolism of pantomime, which were gained through the renunciation of language, served a visualization of the unconscious, the extraneous and pre-linguistic, the dreamlike or traumatic , which Sigmund Freud investigated in depth psychology around 1900 .

One of the most important sponsors of pantomime art at the beginning of the 20th century was Max Reinhardt , who gave it a forum in his cabaret Schall und Rauch , which he co-founded in 1901, and later through collaborations with the poets Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Friedrich Freksa and Karl Vollmoeller as well as the dancer Grete Wiesenthal staged pantomime pieces. With the monumental legendary play Das Mirakel , written by Vollmoeller and premiered in London in December 1911 , Reinhardt achieved the greatest public success of a literary pantomime.

Works and styles

There are two main themes to which the literary pantomimes at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century turned: On the one hand, the traditional and now partly modernized (psychologized) material of the Commedia dell'arte and the Comédie Italienne and their genre-typical staff (the characters of Arlequino and Colombina , Pierrot and Pierrette were particularly popular ); on the other hand, fantastic, fairytale, mythical and mystical - occult stories. - The first category includes pantomimes such as:

- Hermann Bahr: The Good Man's Pantomime (1892)

- Richard Beer-Hofmann: Pierrot Hypnotist (1892)

- Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The Student (1901)

- Karl von Levetzow : Pierrot's Life, Sorrows and Ascension (1902) / The Two Pierrots (1902)

- Arthur Schnitzler: The veil of Pierrette (originated 1892, published 1910) / The Metamorphoses of Pierrot (1908)

- Lion Feuchtwanger : Pierrot's Lord's Dream (1916)

- Louisemarie Schönborn : The White Parrot (1921).

The second category includes works such as:

- Frank Wedekind : The Fleas or The Dance of Pain (1897) / The Empress of Newfoundland (1897) / Bethel (published posthumously in 1921)

- Richard Dehmel : Lucifer (1899)

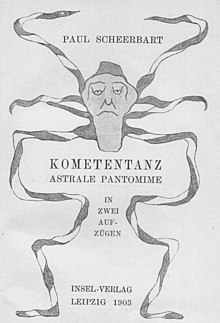

- Paul Scheerbart : Comet Dance (1902) / Secrets (1904) / Sophie (1904)

- Robert Walser : The shot (presumably around 1902)

- Hermann Bahr: Dear Augustin (1902) / The beautiful girl (1902) / The Minister (1903)

- Max Mell : The Dancer and the Puppet (1907)

- Friedrich Freksa: Sumurûn (1910)

- Hugo von Hofmannsthal: Amor and Psyche (1911) / The Strange Girl (1911) / The Bee (1914) / The Green Flute (1916)

- Karl Vollmoeller: The Miracle (1911) / A Venetian Night (1912) / The Shooting Gallery (1921)

- Carl Einstein : Nuronihar (1913)

- Felix Salten: The Alluring Light (1914)

- Carl Hauptmann : Pantomime (undated; presented in 1917, published in 1922)

- Arthur Sakheim : Galante Pantomime (1919)

- Richard Beer-Hofmann: The golden horse (published in 1921/22).

What both types of pantomime have in common, which can also be intertwined - such as in Hofmannsthal's Der Schüler or Schönborn's The White Parrot - are the opening and delimitation of empirical reality through artistic-imaginative design. Formally, the pantomime pieces show dramatic as well as epic and lyrical elements.

In his essay Über die Pantomime , published in 1911, Hugo von Hofmannsthal justified his productive exploration of the art of pantomime by referring to the "pure gesture" of pantomime, renouncing deceptive language, freeing himself from it, making the "true personality" visible and to be able to represent “what is too big, too general, too close to be put into words”. Accordingly, pantomime aroused great interest in many modern poets around 1900, especially because it offered an adequate medium to visualize experiences, conditions and processes beyond language in an effective way, without the poet radically devoting himself to his 'instrument', language had to get rid of. What particularly fascinated the authors of pantomimes about this aesthetic genre was the possibility of expanding and breaking the boundaries of conventional forms of expression with a different, physical language, which was often supported by an atmospheric, atmospherically effective musical accompaniment and into areas of the inexpressible and to penetrate the indescribable.

The literary pantomime - unlike the art of movement in dance or ballet - linguistically shapes the lack of words ; the characters appearing remain silent, but their actions, their movements, their gestures, their gestures and facial expressions are textually ascribed to them. The pantomimic text appears like extensive stage instructions, which are not inserted into the spoken text as scenic remarks, as in word dramas, but which shape and fill out the entire piece.

The performance-based pantomimes 'work' as reading texts insofar as they project (body) images with linguistic reduction and laconicism, moving images of an extraordinary, sensual event that reminds one of the silent film , which has included pantomime elements in a significant way, precisely because the silent film - apart from the inserted text panels - had to forego language for technical reasons.

That the literary mime often simplistic moves reducing and abstracting on the essentials and again and again trashy way appearing situations of extreme experiences of human existence represents the result of the intention to reach a wide, inside 'understanding without an unreliable questionable, inadequate and to need recognized verbal communication and to reach the deepest human realms, regardless of linguistic and social boundaries, where collective perception and recognition is possible. The literary pantomime is to be understood as an aestheticization of emotionality or as a sensualized, vitalized aesthetic form that aims at immediacy, intensity and concentration.

literature

- Hermann Bahr: pantomime. In: Bahr: Overcoming naturalism. Pierson Verlag, Dresden, Leipzig 1891, pp. 45–49.

- Gabriele Brandstetter: Body in Space - Space in the Body. To Carl Einstein's pantomime "Nuronihar". In: Carl Einstein Colloquium 1986. Ed. Klaus H. Kiefer. Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt / M. et al. 1988, pp. 115-137.

- Donald G. Daviau: Hugo von Hofmannsthal's pantomime: The student. Experiment in Form - Exercise in Nihilism. In: Modern Austrian Literature 1, 1968, No. 1, pp. 4-30.

- Heide Eilert: pantomime. In: Reallexikon der Deutschen Literaturwissenschaft. Vol. 3. Ed. Jan-Dirk Müller in collaboration with Georg Braungart, Harald Fricke, Klaus Grubmüller, Friedrich Vollhardt u. Klaus Weimar. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 2003, pp. 8-11.

- Abigail E. Gillman: Hofmannsthal's Jewish Pantomime. In: Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte 71, 1997, no. 3, pp. 437-460.

- Rainer Hank: Mortification and conjuration. On the change in aesthetic perception in modern times using the example of Richard Beer-Hofmann's early work. Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt / M., Bern, New York 1984.

- Astrid Monika Heiss: The pantomime in the old Viennese Volkstheater. Diss. Vienna 1969.

- Hugo von Hofmannsthal: About pantomime. In: Hofmannsthal: Collected works. Vol. 8: Speeches and Essays I, 1891–1913. Edited by Bernd Schoeller in consultation with Rudolf Hirsch. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt / M. 1979, pp. 502-505, ISBN 3-596-22166-8 .

- Robert Alston Jones: The Pantomime and the Mimic Element in Frank Wedekind's Work. Masch. Diss. Austin / Texas 1966.

- Claas Junge: Text in motion. To pantomime, dance and film with Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Diss. Frankfurt / M. 2006.

- Mathias Mayer / Julian Werlitz (eds.): Hofmannsthal manual. Life - work - effect. Metzler Verlag, Stuttgart 2016, pp. 261-272, ISBN 978-3-476-02591-3 .

- Arnaud Rykner (Ed.): Pantomime et théâtre du corps. Transparence et opacité du hors-texte. Presses Universitaires de Rennes 2009, ISBN 978-2-7535-0760-9 .

- Hartmut Scheible: "The Metamorphoses of Pierrot". Arthur Schnitzler and the afterlife of the Commedia dell'arte in Vienna at the turn of the century. In: Staged Reality and Stage Illusion. On the European reception of Goldoni's and Gozzi's theater / Il mondo e le sue favole. Sviluppi europei del teatro di Goldoni e Gozzi (Interdisciplinary conference at the German Study Center in Venice, November 27-29, 2003 ). Edited by Susanne Winter. Edizioni di storia e letteratura, Roma 2006, pp. 139–177.

- Gisela Bärbel Schmid: Cupid and Psyche. On the form of the psyche myth at Hofmannsthal. In: Hofmannsthal leaves. H. 31/32, 1985, pp. 58-64.

- Gisela Bärbel Schmid: "The uncanny experience of a young elegance in a strange visionary night". To Hofmannsthal's pantomime 'The Stranger Girl'. In: Hofmannsthal leaves. H. 34, Herbst 1986 (1987), pp. 46-57.

- Gisela Bärbel Schmid: "A true intellectual dancer partner with rare empathy". Hugo von Hofmannsthal's pantomimes for Grete Wiesenthal. In: Dialect of Viennese Modernism. The dance of Grete Wiesenthal. Edited by Gabriete Brandstetter u. Gunhild Oberzaucher-Schüller. K. Kieser Verlag, Munich 2009, pp. 151-166, ISBN 978-3-935456-23-4 .

- Gisela Bärbel Schmid: The literary pantomime - a so far hardly noticed art form. To a newly published study. In: active word. Vol. 62, August 2012, no. 2, pp. 323-333.

- Edmund Stadler: Pantomime. In: Reallexikon der deutschen Literaturgeschichte. Vol. 3. Ed. Werner Kohlschmidt u. Wolfgang Mohr. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York, 2nd ed. 1977, pp. 1-7.

- Hartmut Vollmer: The poetization of silent dream images. Arthur Schnitzler's pantomime 'The Pierrette's Veil'. In: Sprachkunst. Contributions to literary studies. Vol. 38, 2007, 2nd half volume, pp. 219-241.

- Hartmut Vollmer: The pantomime as a text-interpretative scenic game and as a literary genre in German lessons. In: German lessons. Vol. 62, 2010, no. 4, pp. 90-95.

- Hartmut Vollmer: The literary pantomime. Studies on a genre of modern literature. Aisthesis Verlag, Bielefeld 2011, ISBN 978-3-89528-839-5 .

- Hartmut Vollmer (Ed.): Literary pantomimes. An anthology of silent poetry. Aisthesis Verlag, Bielefeld 2012, ISBN 978-3-89528-954-5 .

- Hartmut Vollmer: Pantomime learning in German lessons. A contribution to the promotion of sensual understanding. Schneider Verlag Hohengehren, Baltmannsweiler 2012, ISBN 978-3-8340-1011-7 .

- Hartmut Vollmer: Arthur Schnitzler: The Metamorphoses of Pierrot / The Veil of Pierrette. In: Schnitzler manual. Life - work - effect. Edited by Christoph Jürgensen, Wolfgang Lukas u. Michael Scheffel. Metzler Verlag, Stuttgart, Weimar 2014, pp. 141-143, ISBN 978-3-476-02448-0 .

- GJ Weinberger: Marionette or "Puppeteer" ?: Arthur Schnitzler's Pierrot. In: Neophilologus. Vol. 86, No. 2, April 2002, pp. 265-272.

- Karin Wolgast: "Scaramuccia non parla, e dice gran cose". To Hofmannsthal's pantomime 'The Student'. In: Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte 71, 1997, no. 2, pp. 245–263.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Hartmut Vollmer: The literary pantomime. Studies on a genre of modern literature. Bielefeld 2011.

- ↑ This and the following information on the history of literary pantomime are taken from Vollmer's study: The literary pantomime. Studies on a genre of modern literature.

- ↑ See Hermann Bahr: Pantomime. In: Bahr: Overcoming naturalism. Dresden, Leipzig 1891, pp. 45–49.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: About the pantomime. In: Hofmannsthal: Collected works. Vol. 8: Speeches and Essays I, 1891–1913. Edited by Bernd Schoeller in consultation with Rudolf Hirsch. Frankfurt / M. 1979, pp. 502-505.