Central Germany

The term means Germany is used to designate a central location in the broadest sense in Germany lying area ; it is used in geographical , linguistic , historical , cultural , economic , political and other contexts.

Since the area is not clearly defined or defined differently depending on the branch of science, the term overlaps with the complex definitions of North , East , South and West Germany .

Since the German unification in 1990 there have been increasing efforts to assign the attribute Central Germany to the states of Saxony , Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia , summarized as a core area. With this in mind, after the flood of the century in 2002, the kick-off event for the Central Germany Initiative took place in Halle (Saale) .

Use of terms

The term Central Germany is used differently by linguists, geographers, historians, spatial planners, business associations and politicians in historical and current contexts. Depending on the point of view, this is either a real region or an area with a constructive character . Before 1800, the Central German attribute was only used in the linguistic-geographical sense. In the 19th century, new structures, compulsions to act and models of thought emerged that changed or supplemented the meaning. Central Germany can be localized in terms of natural and social geography "as a natural area that predetermines a later historical path - or as a more independent, socially created, constructed, symbolically appropriated social and cultural area." The use of Central Germany as a term was at the beginning of the Weimar Republic .

Linguistic term

A linguistic peculiarity of Central German has been handed down as early as 1343. In linguistic terms, Central Germany describes the area in which Central German dialects are widespread, bounded in the north by the Benrath line and in the south by the Main line.

The term Central German originated in the 19th century when the dialects in German-speaking countries were examined. Before, a distinction was only made between Oberland , i.e. H. Upper German and Dutch , d. H. Low German language. In the dialect studies, however, it was found that the High German sound shift , which makes up the historically most striking difference between the Oberland and Dutch languages, is only partially implemented in a very broad strip. Accordingly, the language areas were divided into three. Due to the sound shift and some other features, this strip, which is much wider on the Rhine than in the east, was understood as a transition area between Upper German and Low German. The Central German language area thus represents the area of the Rhine Franconian - Hessian as well as the East Central German dialects and extends in the south from Alsace along the Main line to the Ore Mountains and in the north from Aachen via North Hesse to southern Brandenburg . This is largely in line with the settlement and urbanization of Central Germany during the Middle Ages , which occurred primarily in the Central Rhine and Lower Saxony areas.

This division from north to south was supplemented with a west-east orientation. This arises from the idea of an eastern country handed down in German folk poetry and arose during the German eastern movement in the late Middle Ages. The East Central German dialects (north of the Thuringian Forest , east of the Werra and south of the Benrath Line , i.e. in large parts of what is now called Central Germany) are closest to New High German and Standard German of all German dialects, as the linguist Theodor Frings has proven. The language in the area between Erfurt , Hof , Dessau and Dresden agrees in many ways with New High German. For example, the ick is widely used in the northern dialects and the i in the south , whereas the I is predominant in central German .

This also applies to the vocabulary, as the New High German written language essentially goes back to Martin Luther's translation of the Bible , who saw and used the language of the state officials of the Electorate of Saxony as a model for High German spelling and pronunciation ("I speak after the Saxon Chancellery "). This was, however, a national compensation language and not the same as the spoken dialects of the region .

Geographic term

Central Germany is geographically the middle section of the German low mountain range threshold ; especially in contrast to northern Germany and southern Germany . Such a view prevailed around 1900 and was represented by Albrecht Penck (1887), Joseph Partsch (1904) and Alfred Hettner (1907); accordingly the area extended from the eastern foothills of the Ardennes to the Sudetes . Leipzig, located in the Thuringian or Halle-Leipzig lowland bay , was seen as the center.

This north-south perspective also corresponds to the idea developed after 1990, which describes the area that is bordered by the Harz (in the northwest), the Thuringian Forest and the Franconian Forest (in the southwest), the Ore Mountains and the Lusatian Mountains , the Saxon Switzerland and the Lausitzer Bergland (in the southeast) and the Fläming (in the north). The Thuringian Basin , the Leipzig Lowland Bay and the Central Saxon hill country are located in the interior of Central Germany . The Saale , Mulde and Schwarze Elster all flow to the Elbe in central Germany .

In addition, southern Lower Saxony , northern Hesse and parts of the Franconia region can be counted as part of Central Germany .

Cultural, historical and geographical use of terms

Similarities could already be seen in this area, from the northern stitchery ceramics 7000 years ago through the Schönfeld culture to the northern Aunjetitz culture 4000 years ago. The settlement area of the early Thuringians also mainly comprised parts of what is now Central Germany. But at the time of Charlemagne , the Saale was considered the border to the Sorbs . Depending on the point of view, the space extends to Berlin (from Wittenberg ) or Bavaria (from Weimar ).

According to André Thieme, the domain of the House of Wettin can also be understood as Central Germany in its time. For Karlheinz Blaschke , in connection with the Wettin rule, Saxony occupied Central Germany until the reorganization of Europe at the Congress of Vienna in 1815. The claimed area coincided with a natural area that was encompassed by mountains, i.e. the Ore Mountains, Thuringian Forest and Harz Mountains, as well as a weak dividing line in the north of the Fläming. (But the Principalities of Anhalt belonged to the Ascanians . Therefore, the Wettin domain is only suitable for rough orientation.)

The reference to larger rulers from the Middle Ages and previous times ignores the fact that a transformation through modern times and modernity took place, whereby for Jürgen John a real relationship to Central Germany from 1800 onwards was only shaped by industrialization and modernization processes. A heterogeneous history of this space beforehand, in a historically grown unit, would not exist and would be leveled by common coincidences.

Regional and geographical use of the term

In the 19th century, the Central German states were divided into a geographical north-south division of Prussia in the north and Bavaria , Baden , Württemberg and the Habsburg Monarchy in the south; In doing so, they formed "in nature and people according to their language, their customs and their nature the transition links between northern and southern Germany." In 1836 Volger geographically counted the countries that were located on the Central German Mountains as part of Central Germany. This included the Kingdom of Saxony , the Grand Duchy of Saxe-Weimar , the Duchies of Saxony ( Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha , Duchy of Sachsen-Meiningen and Duchy of Saxe-Altenburg ), the Russian principalities ( Reuss younger line and Reuss older line ), the principalities of Schwarzburg ( Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt and Schwarzburg-Sondershausen ), the Electorate of Hesse , the Grand Duchy of Hesse , the Landgraviate of Hesse-Homburg , the Duchy of Nassau , the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and the Principality of Waldeck . In addition to those mentioned by Volger, Schneider moved into the Duchy of Limburg , the Principality of Lippe-Detmold , the Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe , parts of Prussian Westphalia , parts of the Kingdom of Hanover and the Principality of Anhalt ( Anhalt-Dessau , Anhalt-Bernburg and Anhalt-Köthen ) in 1840. with a.

In 1867, at the end of the German Confederation and the beginning of the German Empire , Brachelli included the Kingdom of Saxony, Thuringia (including the Grand Duchy of Saxony-Weimar, the Saxon duchies and the Black Burgess principalities), the Russian principalities (younger and older lines) among the Central German states , the Electorate of Hesse with Schmalkalden (here areas in the Thuringian Forest and nearby), the Prussian districts ( Erfurt , Schleusingen and Ziegenrück ), the Principality of Waldeck (without Pyrmont) and neighboring Prussian regions.

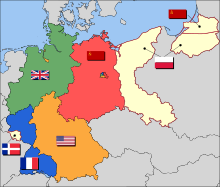

Change through the division of Germany

From 1949 onwards, the German Democratic Republic was also referred to as Central Germany (cf. also the pair of terms East Germany vs. West Germany ), since the government of the Bonn Republic needed linguistic instruments until the policy of détente and recognition of the GDR as a state so as not to give Moscow's westernmost province the state name to have to designate. Before the GDR was recognized, the population of the FRG mainly spoke of the East Zone , this term being derived from the Soviet Occupation Zone (SBZ). From the mid-1960s, the terms and spellings so-called GDR , later only "GDR" (in quotation marks ), were more common. After the GDR was recognized, the quotation marks were left out. Since German reunification, the terms new countries or East Germany have mostly been used for the former territory of the GDR .

The term Central Germany was used as a synonym for GDR in official documents of the Federal Republic of Germany. Mitte referred to the situation of the GDR between the Federal Republic in the west and the formerly German areas in the east of the Oder-Neisse border . On the maps published by government agencies, such as those hung in the wagons of the Bundesbahn , Germany was still depicted within the borders of 1937 . This use of the term declined in the 1970s. However, the narrower use of the term was also retained in West Germany, for example the research center for historical regional studies of Central Germany in Marburg endeavored to do so.

See for example: Historians in Central Germany

The use of the term Central Germany by parts of the West German population in the period up to 1969 reflected their attitudes and, in particular, the attitudes of the associations of expellees who were not prepared to finally recognize the border shift made at the Yalta and Potsdam conferences . In fact, at the Potsdam Conference in the summer of 1945 it was expressly stated that the new German-Polish border should only be established in the course of a future peace settlement . Consequently, in the post-war period in West Germany, the designation East Germany was sometimes used for the areas east of the Oder-Neisse Line and Central Germany for the GDR. A displaced newspaper stated in 1984:

- As yesterday, the term East Germany includes the areas beyond the Oder and Neisse rivers - unless one is prepared to erase more than a thousand years of German history from memory. The territory claimed by the SED state must, according to all logic, be categorized as Central Germany. It would be correct to designate this area as 'Soviet-occupied Central Germany'.

At the request of the victorious powers, recognition of the Oder-Neisse border became the prerequisite for their approval of German unity. As the national border of all of Germany and Poland, this border was anchored in an international treaty on November 14, 1990 by the Two-Plus-Four Treaty .

In the Soviet occupation zone, the term was initially used in summary for the states of Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia and Saxony. With the deepening of the division of Germany, the term last used synonymously with East Germany or Eastern Zone, which anticipated the later equation of GDR and Central Germany, took a back seat. From the mid-1950s, the meanwhile prevailing West German interpretation of the term found decisive rejection in the GDR and Poland. The older Central Germany term was still used sporadically, but disappeared during the 1960s. In some cases, this term from Central Germany experienced a renaissance for the entire GDR in 1989/90, but was not able to prevail against the now established East Germany.

Use of botanical-geographic terms

For the botanist Oscar Drude , the Hercynian flora district , an area in the geobotanical division of space (cf. Florenreich ), about which he wrote a work in 1902, was representatively equated with the area of Central Germany. This view was also represented by Hermann Meusel . The Hercynian flora district comprises the low mountain range north of the Alps of central and eastern Germany (and the Czech Republic), including the Harz, Rhön, Bavarian and Bohemian Forests and the Ore Mountains. The north German lowlands do not belong to it, neither does the lowland portion of Saxony-Anhalt north of the Harz Mountains.

Folklore contemplation

According to Michael Simon, Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl's definition of the term from 1867 first introduced Central Germany into folklore. According to Rhiel, Central Germany is decisive in a three-part area that extends from north to south and is a large triangle between Silesia , Lake Constance and the Prussian-Belgian border near Aachen, with the exact borders remaining undefined. According to Riehl, the difference to the two other parts of the country lay in the extensive fragmentation and individualization of popular life.

The perspective narrowed in the 1930s with the creation of the Atlas of German Folklore (ADV), which takes up the Central Germany term of the linguistic usage of the time for the Saxon-Thuringian area. In addition to the study on the Rhineland in 1926, there was also a study on the cultural areas and cultural currents in East Central Germany . After Michael Simon, however, the author Gerhard Streitberger did not succeed in dealing with the folk-cultural phenomena between the Thuringian Forest, the Ore Mountains and the Harz Mountains. Gerhard Streitberger only stated that Saxony, which was the starting point of the investigation, appeared to be more closely connected to the Silesian and Sudeten German regions in the area of folklore.

During his time in the Federal Republic of Germany, Matthias Zender attempted to evaluate the data again. According to his interpretation, there were peculiarities that stood out in Thuringia and Saxony and, from a folklore point of view, made Saxony the most modern landscape in Germany around 1930, which was best adapted to the requirements of the industrial society of that time. With the same material from the ADV, similar findings were made during the later investigation by Gerda Grober-Glück, who found that, in addition to the early adoption of innovations, there were also creative transformations of traditional forms. According to Simon, there is little research in modern folklore about understanding Central Germany as an objective cultural area, which deals with clichés, prejudices, stereotypes and the like.

The Central Germany idea as a state and regional education concept

The idea of the formation of a country in Central Germany or such a region goes back to the 19th century. As early as 1819, the idea of joining forces with Saxony in the field of customs policy arose in the Grand Duchy of Saxony-Weimar. There was a temporary political development as a merger of countries located in the middle of Germany to form the Mitteldeutscher Handelsverein , which was supposed to represent the interests of the small states vis-à-vis the Prussian-Hessian customs union , but only existed from 1828 to 1834.

In 1849, Bernhard von Waldorf, Minister of State of Saxony-Weimar, presented the draft to bring all Thuringian states into close relations with Saxony. This even included a Saxon-Thuringian army constitution. However, there was never any political implementation. Even during the German Revolution of 1848/1849 , thoughts of political unity flared up in the area of the princes and duchies. Under the Saxon crown, the small Thuringian states and Anhalt duchies were to merge with the Kingdom of Saxony.

With the dissolution of the German Empire in 1918, Thuringia's dynastic turmoil ended, but here, too, the center stayed away, as the area around Erfurt was still part of Prussia. During the time of the Weimar Republic there were again numerous memoranda on regional and country formations. In 1927 the governor of the Prussian province of Saxony, Erhard Hübener , proposed a unification of the territories with the writing Mitteldeutschland on the way to unity , which, however, could not prevail against the regional particularism of this time. The reorganization debate of the 1920s and 1930s came to an end when the representatives of the NSDAP elected in 1933 , as they spatially divided the German Reich into Gaue between 1933 and 1945 .

After the end of the Second World War, a new order was first pushed forward by the American occupation forces and later by the Soviet administration . At the head of a new German administration stood Erhard Hubener, left in the belief by the Americans that he could act as the reinstated governor of a central German province that was not described in detail. With the transition to the Soviet occupation zone, the Soviet authorities appointed him as president of a province called Saxony. The new province was partially identical to the previous one and now comprised parts that corresponded to his 1929 concept of a central German part of Saxony-Anhalt. However, this time, too, there was no further amalgamation of the newly established states, since with the emergence of the German Democratic Republic, territorial reforms that did not envisage central Germany again came into effect. Instead, the GDR territory was divided into districts .

With German unification, there was political will to implement Central Germany as a regional development concept. However, the idea was not realized. The underlying merger idea was repeatedly brought up in the debate in vain. The main sponsor of the idea was the Aktion Mitteldeutschland association founded in 1992 , which was initiated by the Halle-Dessau Chamber of Commerce and Industry . In terms of state politics, for example, Saxony's Interior Minister Klaus Hardraht made an advance in 1998 , but this was rejected a little later by the representatives of Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt. Mostly it was about cooperation initiatives with structure-building goals and the idea of a merger through cooperation. Local and state political implementation are naturally protracted. Economic initiatives have so far achieved the most promising real development.

Since the accession of the GDR to the Federal Republic of Germany (reunification), the region around the triangle formed by the federal states of Saxony , Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia has increasingly been referred to as Central Germany. However, Hesse must also be included, since after the establishment of the Free State of Thuringia, both countries have institutional links and have cooperated closely with one another. In 1992 the Landesbank Hessen-Thüringen was established as part of this cooperation between the two federal states by means of a state treaty. There are also organizations such as the DGB or the ADAC that have a Hessian-Thuringian regional association.

Central Germany Initiative

Since 2002, the state governments of Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia have wanted to cooperate more closely with one another in the Central Germany Initiative .

Among other things, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia are linked to one another through the following aspects:

- The Thuringian-Upper Saxon dialects are spoken in Saxony, in the southern part of Saxony-Anhalt and in the part of Thuringia north of the Rennsteig .

- Large parts of the area belonged to the Wettin domain , which was divided between the lines of the Ernestines (Thuringia) and Albertines (Saxony) after the division of Leipzig (1485) .

- Saxony and Thuringia in particular are better developed economically than the structurally weaker northern new states of Brandenburg and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania .

Country merger

In 2005, Leipzig's Lord Mayor Burkhard Jung and the then Lord Mayor of the City of Halle Dagmar Szabados spoke out in favor of a merger of the three federal states into a federal state of Central Germany in 2018 - but this was rejected by the concerned Prime Ministers in May 2011.

The consent of the population in Saxony and Thuringia, the name of the new federal state, the seat (s) of the constitutional bodies and the structure below the state level are also viewed as problematic.

In 2013, member of the state parliament, Bernward Rothe , initiated a collection of signatures, which achieved the required number of votes for a referendum at the end of 2014. The then submitted application for a referendum to bring about a uniform nationality for this area was rejected on September 30, 2015 by the Federal Ministry of the Interior as “inadmissible and unfounded”. The reorganization area designated in the applications is not a contiguous, delimited settlement and economic area within the meaning of Article 29 (4) of the Basic Law. On November 2, 2015, Rothe lodged a complaint with the Federal Constitutional Court against this decision as the initiative's shop steward. The constitutional complaint was rejected in 2019.

If the Federal Constitutional Court had allowed the complaint, the referendum would have been declared valid. The success of a referendum, the Bundestag must in a period of two years either grant the request or a plebiscite perform. According to Article 29 (5) of the Basic Law, as an alternative to the full merger of the federal states of Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia, a partial merger could be submitted as a proposal for the referendum. The division of Saxony-Anhalt would also be possible. A reorganization of the federal territory decided in this way does not require any additional legitimation in an obligatory referendum .

Institutional and economic cooperation

As early as the first half of the 20th century, the term Central Germany was used specifically for the area around Halle (Saale) - Leipzig , where people spoke of the Central German industrial area, today's Central German chemical triangle .

Various cluster initiatives have recently been set up. The important sectors include the automotive and supplier industry, which already played an important role in Saxony and Thuringia when it was founded ( Auto Union ), as well as the high-tech sector with centers in Jena (e.g. Jenoptik ), Dresden ( Silicon Saxony ) and Leipzig ( Biotechnology). The European metropolitan region of Central Germany , based in Leipzig, is also located in the so-called Central Germany Economic Area . Today the conurbation of Leipzig-Halle forms the center of this economic area: This is where Leipzig / Halle Airport , the important Leipzig main train station and the central German motorway loop are located .

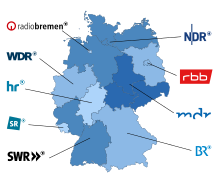

Central German radio

The Central Germany term is increasingly being used for the entire broadcast area; at the latest since 1992, when the broadcasting corporation MDR- Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk began broadcasting . This has to create the transmission order identity. The MDR produces content to popularize the Central Germany idea for the three states of Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia, which are designated as the broadcasting area. Programs such as the history of Central Germany are intended to raise awareness of historical similarities and differences between the individual regions.

Middle German as part of the name

- historical:

- The Central German peasant uprising of the 16th century

- The central German general strike in 1919

- The Central German Uprising (1921)

- Mitteldeutsche Creditbank in Frankfurt am Main and Berlin from 1856

- The Mitteldeutsche Stahlwerk AG from Berlin from 1909,

- The Central German Brown Coal Syndicate in Leipzig

- The Central German steelworks in Riesa in 1926

- The Mitteldeutsche Rundfunk AG (MIRAG) broadcasting company and one of the oldest radio stations in Germany in the 1920s / 30s

- The Association of Central German Ball Game Clubs , 1900 to 1933

- modern:

- The Mitteldeutsche Verkehrsverbund (MDV) is a public transport association in the greater Leipzig-Halle area.

- The S-Bahn Central Germany operates primarily in the Leipzig-Halle conurbation, but has also included Altenburg and Zwickau .

- The Evangelical Church in Central Germany was created at the beginning of 2009 through the merger of the Evangelical Church of the Church Province of Saxony and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Thuringia .

- Central German marathon

- The Mitteldeutsche Zeitung has been the name of the former organ of the SED district leadership in Halle since 1990.

- The Mitteldeutsche Presse appears in Fulda .

- The Central German publishing house (mdv) is an independent publisher based in Halle (Saale) and Leipzig.

- The Mitteldeutscher Kulturrat Foundation , which publishes the Central German Yearbooks, is a product of the period from 1945 to 1990 and feels obliged to all of the New Laender - with a tendency towards today's language usage.

- MIFA Mitteldeutsche Fahrradwerke

- The Central German brown coal company mbH (MIBRAG) is a company that deals with the promotion and partial processing of lignite in various locations in Saxony-Anhalt and Saxony.

- At the Leuna chemical site , Total Raffinerie Mitteldeutschland GmbH is the company with the highest turnover in the new federal states.

exactly covering the area of the federal states of Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia

- German Pension Insurance Central Germany (since 2005)

- Handball-Oberliga Mitteldeutschland (since 2010)

- Self-employed in Central Germany is an initiative that has been running since 2016, including the online portal of the Thuringia, Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt state associations of the Confederation of Self-Employed Persons .

- An online magazine based in Leipzig has been calling itself Startup Central Germany since 2017.

Reception and criticism of the use of the attribute Central German

The historian Jürgen John does not identify a clearly definable term for Central Germany. The idea of a Central Germany is indeterminate, complex and ambiguous due to its frequent change over time. The Central Germany idea has been in the discourse since the 19th and 20th centuries. Central Germany is mostly a projection screen. John is of the opinion that those who “started from a supposedly well-defined“ Central German ”cultural, economic, historical and identity space ” only demonstrated their talent “to design appropriate spatial and historical images, their own desires Projecting interests and design intentions onto them and using history as an argument, as it were . Spatially close countries are often apostrophized as South, West, North, East or Central German , which are assigned certain similarities and historical similarities, are therefore subject to the great temptation to misunderstand and interpret them as closed spaces of history and identity.

For Karlheinz Blaschke, Central Germany is not a dream. The term was firmly established in linguistic usage, since geography knew the term Mitteldeutsches Gebirgsland, linguistics knew the Central German dialect, and the mid-19th century economy combined spatial units and businesses with the name Mitteldeutsch . For example, he cites the historical and regional work of the Central German Heimatatlas by the geographer Otto Schlüter . But he also accuses today's central German federal states of Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia of immobility in connection with the formation of a central Germany , which would be reminiscent of the small states of the 19th century.

Divergent feelings of belonging

Residents of northern Saxony-Anhalt feel connected to the Brandenburg - Prussian past, as indicated by club names such as Magdeburger SV 90 Preussen . In southern Thuringia, part of the population is committed to the Hessian or Franconian tradition. The Sorbs are mainly based in Lusatia , which is divided into Upper Lusatia in Saxony and Lower Lusatia in Brandenburg . The cultural-historical ethnic group is regionally cut off from one another.

Even the Central Germany Economic Initiative did not reorient the term in which parts of Hesse, Bavaria or Lower Saxony would have been perceived as part of Central Germany. Brandenburg on the border with Poland is therefore in East Germany, but Saxony is not. By equating it with federal states, it is deliberately ignored that Görlitz , the easternmost city in Germany, would have to be geographically in eastern Germany, since the natural border would be the upper reaches of the Elbe at the latest .

Saxony

The Free State of Saxony is located on the eastern border of today's Federal Republic and can therefore only be considered Central German from a north-south perspective.

Hesse

The state of Hesse is closer to the geographic center of Germany than, for example, many districts in Saxony-Anhalt or Saxony, but has often not been included in the area referred to as Central Germany in recent times. The reasons for this are that Hesse belonged to the so-called old federal states in recent history , while the areas of Saxony-Anhalt, Saxony and Thuringia - due to the common belonging to the national territory of the former GDR - can be attributed to the new states . With the Hessischer Rundfunk , Hessen also has its own broadcasting corporation and, with the Rhine-Main area around Frankfurt am Main, a key region in the southwest. The state capital Wiesbaden is also located on the Rhine and thus in western Germany.

See also

literature

- Tilo Felgenhauer: Geography as an argument. An investigation of regionalising justification practice using the example of “Central Germany”. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2007.

- Monika Gibas : In search of the “German heartland”. “Middle” myths in Germany between the wars (1919 to 1939) and after 1990. In: Rainer Gries, Wolfgang Schmale (ed.): Culture of Propaganda (= challenges. Volume 16). Bochum 2005, pp. 195-210.

- Jürgen John : "Central Germany" pictures. In: History of Central Germany. The companion book to the television series. Stekovics, Halle (Saale) 2000, ISBN 3-932863-90-9 .

- Jürgen John (Ed.): "Central Germany". Concept - history - construct. Rudolstadt et al. 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 ( review by Peter Huebner in H-Soz-u-Kult, January 18, 2002).

- Jürgen John: "Central Germany". Outlines of a research project. Mitten und Grenzen, 2003, pp. 108–144.

- Jürgen John: "German center" - "European center". On the entanglement of the “Central Germany” and “Central Europe” discourses. In: Detlef Altenburg, Lothar Ehrlich, Jürgen John (eds.): In the heart of Europe: national identities and cultures of remembrance. Verlag Böhlau, 2008, pp. 11–80.

- Steffen Raßloff : Central German history. Saxony - Saxony-Anhalt - Thuringia , Leipzig 2016, revised new edition Sax Verlag, Markkleeberg 2019, ISBN 978-3-86729-240-5 .

- Michael Richter (historian) , Thomas Schaarschmidt, Mike Schmeitzner (ed.): Länder, districts and districts. Central Germany in the 20th century. Halle 2008, ISBN 978-3-89812-530-7 .

- Klaus Rother (Ed.): Central Germany yesterday and today. Passau 1995, ISBN 3-86036-024-8 .

- Antje Schlottmann: What is and where is Central Germany? A slightly different geography. In: Geographical Rundschau. 6/59, 2007, pp. 4-9.

- A. Schlottmann, M. Mihm, T. Felgenhauer, S. Lenk, M. Schmidt: "We are Central Germany!" - Constitution and use of territorial reference units under spatio-temporally unanchored conditions. In: Benno Werlen (Ed.): Social geography of everyday regionalizations. Volume 3: Empirical Findings. Stuttgart 2007, pp. 297-334.

- Claudia Schreiner, Katja Wildermuth (Hrsg.): History of Central Germany. Of rulers, witches and spies. Sandstein, Dresden 2013, ISBN 978-3-95498-042-0 .

- Bernhard Sommerlad : Central Germany in German history. In: Mitteldeutscher Kulturrat (Ed.): From the middle of Germany. Part 3: Central Germany - Attempts at a conceptual definition under technical aspects. Bonn 1978, pp. 25-58.

- Marina Ahne: Central German industrial landscapes - identification between continuity and change. In: Sachsen-Anhalt-Journal. 26 (2016), no. 4, ISSN 0940-7960, pp. 19-21. (j journal.lhbsa.de ).

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Distinctive innovations were for example: cigars and toothbrushes were given to the dead as grave goods and a dummy hymn book was placed in their hands when they parted. Annual fires had lost their traditional character. Instead, fires took place on Sedan Day, for example, and light parades for political celebrations, even during the Weimar period; the annual fire of the youth leagues and midsummer celebrations of the National Socialists met with approval. Mother's Day, which came into custom from America at the end of the First World War in 1918, was already 90 to 100 percent widespread in Saxony and parts of Thuringia in 1932. Even in cities like Cologne or Hamburg, these values were not achieved.

Individual evidence

- ↑ "The Prime Minister of Saxony-Anhalt, Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Böhmer said in his speech that a “common agenda for the three central German states has been drawn up, in which we set out the areas in which we are striving for closer cooperation in the future”. “ Sachsen-Sachsen-Anhalt-Thüringen @ Neugliederung-bundesgebiet.de , accessed May 10, 2015.

- ↑ Jürgen John : Shape and change of the "Central Germany" pictures . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 17th f .

- ↑ Jürgen John: Shape and change of the "Central Germany" pictures . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 18 .

- ↑ Jürgen John: Shape and change of the "Central Germany" pictures . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 20 .

- ↑ Jürgen John: Shape and change of the "Central Germany" pictures . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 61 .

- ^ A b c d e f g h i Karlheinz Blaschke : Geographical framework conditions of political organization in Central Germany . In: Michael Richter, Thomas Schaarschmidt, Mike Schmeitzner, State Center for Civic Education Saxony (ed.): Länder, Gaue and districts . Central Germany in the 20th century. First edition. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-89812-530-7 , pp. 36 .

- ^ A b Günther Schönfelder : Central Germany from a geographical point of view . Attempt at an interpretation. In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 161 .

- ↑ Werner König: dtv Atlas German Language, p. 120, Fig. Central Germany as a geographical term

- ↑ Helmut Castritius, Dieter Geuenich, Matthias Werner, Thorsten Fischer: The early days of the Thuringians: archeology, language, history. Volume 63 of Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde - supplementary volumes, Verlag Walter de Gruyter, 2009, p. 345.

- ↑ see Limes Sorabicus

- ↑ see e.g. B. Central Germany Regional Park , accessed November 16, 2014; Bernd Kulla: The beginnings of empirical business cycle research in Germany 1925–1933. Duncker & Humblot Publishing House, Berlin 1996, p. 79.

- ↑ André Thieme: The Förderalismusbegriff Through the Ages - an approximation . In: Michael Richter, Thomas Schaarschmidt, Mike Schmeitzner, State Center for Civic Education Saxony (ed.): Länder, Gaue and districts . Central Germany in the 20th century. First edition. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-89812-530-7 , pp. 21st f . (Quote: The medieval and early modern Wettin rule in Central Germany is, [...]. With a footnote to Central Germany: For the term Central Germany see Wolf, Wandlungen des “Mitteldeutschland”, pp. 3–24; Blaschke, Central Germany as historical and regional Term, pp. 13–24; Rutz, Mitteldeutschland. In Gesellschaft und Kultur Volume 1, pp. 225–258).

- ↑ Jürgen John: Shape and change of the "Central Germany" pictures . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 20 .

- ↑ z. B. Hugo Franz von Brachelli : The states of Europe in a short statistical representation. 1867, p. 11 .; Jürgen John 2008, p. 43.

- ^ A b K. F. Robert Schneider: Deutsche Vaterlandskunde . IV edition. Publishing house by Carl Heyder, Erlangen 1840, p. 42, 162–231 ( limited preview in Google Book search). | Comment = mentioned areas for Central Germany : The Dutch. Grand Duchy of Luxembourg with the Duchy of Limburg, Duchy of Nassau, Kurhessen or Hessen-Kassel, Fürstenthum Waldeck, Fürstenthum Lippe-Detmold, Fürstentum Schaumburg Lippe, parts of Prussia. Westphalen, parts of the Kingdom of Hanover, Duchy of Braunschweig, Grand Duchy and Duchy of Saxony (Duchy of Saxony-Meiningen-Hildburghausen, Duchy of Saxony-Koburg-Gotha, Grand Duchy of Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach, Duchy of Saxony-Altenburg), Principality of Reuss, Principality of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, Principality of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen, Duchies of Anhalt (Anhalt-Dessau, Anhalt-Bernburg, Anhalt-Köthen), Kingdom of Saxony

- ^ WF Volger: Handbook of Geography . IV edition. Hahn'sche Hofbuchhandlung, Hanover 1838, p. 42, 162–231 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Hugo Franz Brachelli: The states of Europe in a short statistical presentation . II edition. Buschak & Irrgang, Brünn 1867, p. 11 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ A b Jürgen John: Shape and change of the "Central Germany" images . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 63-67 .

- ↑ Words shape concepts . Wehlau home letter . 1984.

- ↑ Andreas Morgenstern: "Central Germany": a battle expression? The change in terminology in the GDR daily Neue Zeit | bpb. Federal Agency for Civic Education, accessed on May 30, 2018 .

- ↑ Andreas Morgenstern: "Central Germany": a battle expression? The change in terminology in the GDR daily Neue Zeit | bpb. Federal Agency for Civic Education, accessed on May 30, 2018 .

- ↑ Oscar Drude : The Hercynian Floral District . Basic features of the plant distribution in the central German mountain and hill country from the Harz to the Rhön, to the Lausitz and the Bohemian Forest. Ed .: Wilhelm Engelmann. Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig 1902 ( Oscar Drude: "The Hercynian flora district: Basic features of the plant distribution in the central German mountain and hill country from the Harz to the Rhön, to the Lausitz and the Bohemian Forest" ).

- ↑ Michael Simon: The term Central Germany from a folklore perspective . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 207 f .

- ↑ Michael Simon: The term Central Germany from a folklore perspective . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 210-212 .

- ↑ Michael Simon: The term Central Germany from a folklore perspective . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 212-213 .

- ↑ Michael Simon: The term Central Germany from a folklore perspective . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 214 f .

- ^ A b Karlheinz Blaschke: Geographical framework of political organization in Central Germany . In: Michael Richter, Thomas Schaarschmidt, Mike Schmeitzner, State Center for Civic Education Saxony (ed.): Länder, Gaue and districts . Central Germany in the 20th century. First edition. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-89812-530-7 , pp. 38 f .

- ^ Karlheinz Blaschke: Geographical framework for political organization in Central Germany . In: Michael Richter, Thomas Schaarschmidt, Mike Schmeitzner, State Center for Civic Education Saxony (ed.): Länder, Gaue and districts . Central Germany in the 20th century. First edition. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-89812-530-7 , pp. 39 .

- ^ Karlheinz Blaschke: Geographical framework for political organization in Central Germany . In: Michael Richter, Thomas Schaarschmidt, Mike Schmeitzner, State Center for Civic Education Saxony (ed.): Länder, Gaue and districts . Central Germany in the 20th century. First edition. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-89812-530-7 , pp. 41 .

- ^ A b Mathias Tullner : Erhard Hübener and the Province of Saxony . Central Germany plans and imperial reform. In: Michael Richter, Thomas Schaarschmidt, Mike Schmeitzner, State Center for Civic Education Saxony (ed.): Länder, Gaue and districts . Central Germany in the 20th century. First edition. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-89812-530-7 , pp. 82 f .

- ↑ a b c Jürgen John: The idea of "Central Germany". Association of German Engineers , March 7, 2007, accessed on May 21, 2015 ( The text is based on a lecture given on March 7, 2007 at the Berlin Representation of the State of Saxony-Anhalt on the Central German Evening of the Business Initiative for Central Germany eV The written version follows the verbal presentation and dispenses with comments. ).

- ^ Günther Schönfelder: Central Germany from a geographical point of view . Attempt at an interpretation. In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 162 .

- ↑ Jürgen John: Shape and change of the "Central Germany" pictures . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 35 f .

- ^ Werner Rutz : restructuring concepts after 1990 . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 455 .

- ↑ Neues Bundesland Mitteldeutschland (LVZ) ( Memento of the original from June 29, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Referendum in Central Germany. “After the federal election in September 2013, the collection of signatures for a referendum in accordance with Article 29, Paragraph 4 of the Basic Law began in the Halle-Leipzig settlement and economic area. The two cities of Halle (Saale) and Leipzig, together with the three directly adjacent districts of Leipzig, North Saxony and Saalekreis, form a suitable area for collecting signatures ... c / o Bernward Rothe. Member of the State Parliament of Saxony-Anhalt ”, accessed on May 10, 2015.

- ↑ On the (first) home straight: Central German referendum has collected enough votes for the first hurdle Leipziger Internet Zeitung December 17, 2014.

- ↑ Referendum Mitteldeutschland , Neugliederung-bundesgebiet.de, accessed on September 15, 2015.

- ↑ Decision of the Federal Ministry of the Interior September 30, 2015 , Neugliederung-bundesgebiet.de, accessed on November 5, 2015.

- ↑ Complaint of November 2, 2015 to the Federal Constitutional Court regarding the admission of a referendum in accordance with Art. 29 para. 4 GG in the Leipzig / Halle (Saale) area , Neugliederung-bundesgebiet.de, accessed on November 5, 2015.

- ↑ Federal Constitutional Court, decision of March 13, 2019, 2 BvP 1/15

- ↑ Referendum wants to split off Halle . volksstimme.de, accessed on September 3, 2015.

- ↑ Mitteldeutschland.de ( Memento from March 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Jürgen John: Shape and change of the "Central Germany" pictures . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 20 .

- ^ A b Jürgen John: Shape and change of the "Central Germany" images . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 43 .

- ↑ Central German yearbooks

- ↑ https://selbstaendig-in-mitteldeutschland.de/mitmachen/ueber-uns/

- ↑ www.mitteldeutschland.com (PDF 217 kB)

- ↑ Jürgen John: "Thuringian Question" and "German Center" . The state of Thuringia in the field of tension between endogenous and exogenous factors. In: Michael Richter, Thomas Schaarschmidt, Mike Schmeitzner, State Center for Civic Education Saxony (ed.): Länder, Gaue and districts . Central Germany in the 20th century. First edition. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-89812-530-7 , pp. 35 .

- ^ Karlheinz Blaschke: Geographical framework for political organization in Central Germany . In: Michael Richter, Thomas Schaarschmidt, Mike Schmeitzner, State Center for Civic Education Saxony (ed.): Länder, Gaue and districts . Central Germany in the 20th century. First edition. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-89812-530-7 , pp. 35 .

- ^ Karlheinz Blaschke: Geographical framework for political organization in Central Germany . In: Michael Richter, Thomas Schaarschmidt, Mike Schmeitzner, State Center for Civic Education Saxony (ed.): Länder, Gaue and districts . Central Germany in the 20th century. First edition. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-89812-530-7 , pp. 41 .

- ^ Karlheinz Blaschke: Geographical framework for political organization in Central Germany . In: Michael Richter, Thomas Schaarschmidt, Mike Schmeitzner, State Center for Civic Education Saxony (ed.): Länder, Gaue and districts . Central Germany in the 20th century. First edition. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-89812-530-7 , pp. 42 .

- ↑ z. B. “Ominous Franconian Consciousness” , sueddeutsche.de, February 10, 2013, accessed January 10, 2015.

- ↑ Jürgen John: Shape and change of the "Central Germany" pictures . In: Jürgen John, State Center for Political Education Saxony (Ed.): "Central Germany" . Concept - history - construct. 1st edition. Hain, Rudolstadt / Jena 2001, ISBN 3-89807-023-9 , pp. 23 .