Sorbs

The Sorbs ( Upper Sorbian Serbja , Lower Sorbian Serby , especially in Lower Lusatia in German also Wenden , German obsolete or Lusatian Serbs in the Slavic languages to this day ) are a West Slavic ethnic group that lives mainly in Lusatia in eastern Germany . It includes the Upper Sorbs in Upper Lusatia in Saxony and the Lower Sorbs / Wends in Lower Lusatia in Brandenburgthat differ linguistically and culturally. The Sorbs are recognized as a national minority in Germany . In addition to their language, they have an officially recognized flag and anthem . As a rule, Sorbs are German citizens .

In the Middle Ages , a tribe of the same name settled between the Saale and Mulde . It is not identical to the ancestors of today's Sorbs - Lusizians and Milzenians - but the southern part of the Elbe Slavic tribes is generally summarized as "Sorbian" due to the linguistic relationship.

Language and settlement area

Settlement area

According to official information, there are around 60,000 Sorbs. These figures are based on projections from the 1990s. On the basis of self-attribution, 45,000 to 50,000 Sorbs were identified, and around 67,000 Sorbs based on active language skills. About two thirds of them live in Upper Lusatia in Saxony , mainly in the Catholic triangle between the cities of Bautzen , Kamenz and Hoyerswerda (in the five municipalities on Klosterwasser and in the municipality of Radibor and parts of the municipalities of Göda , Neschwitz , Puschwitz and in the city of Wittichenau ). In the official Sorbian settlement area in Saxony, the proportion of Sorbs is estimated at an average of 12% and amounts to around 0.9% of the total population of Saxony. One third lives in Niederlausitz, mainly between Senftenberg in the south and Lübben in the north, 90% of which live in the Spree-Neisse district and the independent city of Cottbus . In the German-Sorbian parts of the districts in Brandenburg, the proportion of Sorbs is estimated to be 7% on average and about 0.8% of the total population of Brandenburg.

In the 1880s, the core settlement area comprised larger areas south and east of Bautzen (to Kirschau , Oelsa and Bad Muskau ) and north of Cottbus, in which the language is no longer spoken today.

East of the Neisse, on what is now Polish territory, Sorbs lived well into the 20th century. The center of their culture and language in German times was the city of Sorau (Sorbian Žarow, today Polish Żary ). Until the 18th century, women and girls wore the traditional Sorbian Sorau costume, but Sorbian was increasingly disadvantaged or even suppressed by the Prussian politics of the time. From this and from naturally occurring assimilation processes it resulted that between 1843 and 1849 approx. 4–5% of the Sorau population referred to themselves as Sorbs, but only approx. 1–2% in 1890 and in 1905 only 0.1%. Today the language of the population is almost exclusively Polish, few have German as their mother tongue. The Sorbian population at that time was Germanized and at the end of the Second World War largely expelled because they were German citizens . The few remaining Sorbs in Poland were assimilated into the Polish people.

Sorbian language

There are two written languages ( standard varieties ) of the Sorbian language , Upper Sorbian ( hornjoserbšćina ) and Lower Sorbian ( dolnoserbšćina ) , but a distinction is usually made between Lower Sorbian, Upper Sorbian and the group of border dialects in between. The Lower Sorbian language is acutely threatened with extinction. While Upper Sorbian is closer to Czech and Slovak , Lower Sorbian is more similar to Polish .

According to estimates by Sorbian institutions ( Domowina , Sorbian Institute ), there are now 20,000 to 30,000 active speakers of both Sorbian languages; according to other projections, Lower Sorbian has only 7,000 active speakers and Upper Sorbian around 15,000. The core of the Upper Sorbian area, in which Sorbian is everyday language and is used by the vast majority of the population, are the communities of Crostwitz , Ralbitz-Rosenthal , Panschwitz-Kuckau , Nebelschütz and Räckelwitz as well as parts of the neighboring communities of Neschwitz, Puschwitz and Göda. Another center is the municipality of Radibor. In Lower Lusatia, one can no longer speak of a stable core area in this form. Most of the Lower Sorbian native speakers can be found in the communities between the Spreewald and Cottbus.

Transitional dialects, the so-called Sorbian border dialects, are spoken in a strip from Bad Muskau in the east via loop to Hoyerswerda in the west . They differ considerably from both standard languages.

Sorbian emigration

Due to the prevailing poverty in the rural areas of the German Federal mid-19th century also occurred in the Lausitz to a migration of small Sorbian population.

A group of over 500 Sorbs under the leadership of the Evangelical Lutheran pastor Jan Kilian sailed in 1854 on the ship "Ben Nevis" to Galveston . They later founded the Serbin settlement in Lee County, Texas, near Austin . Two thirds of the emigrants came from the Prussian, one third from the Saxon part of Upper Lusatia, including about 200 Sorbs from the area around Klitten . The Sorbian language, a variant of Upper Sorbian that was first strongly influenced by German and later by English , persisted until the 1920s . In the past, newspapers were also published in Sorbian in Serbian. Today, the former Sorbian school in Serbin houses the Texas Wendish Heritage Museum , which reports on the history of the Sorbs in the USA. Descendants of these emigrants founded Concordia University Texas in 1926 in the Texas capital Austin .

There were other Sorbian settlements - mostly together with German emigrants - in various areas of Australia, especially in the south of Australia . In the years 1848 to 1860, most of the Sorbs, around 2000 in 400 families, a large number of them came with the ships “Pribislaw” and “Helena”. In Australia, too, the Sorbian language was strongly influenced by German, as the Sorbs mostly moved to the German-influenced regions of Australia due to a lack of knowledge of English. The last descendant of the Sorbian immigrants who still spoke the language died in Sevenhill in 1957 .

religion

Most of the Upper Sorbian speakers are now Catholic. Originally, the majority of the Sorbs were Protestant Lutheran until the 20th century (86.9% in 1900), only 88.4 of the Sorbs of the Kamenz district - settled mainly on the extensive former property of the St. Marienstern monastery - were % Catholics. In Lower Lusatia, on the other hand, their share was consistently below one percent. Due to the rapid loss of language and identity among the Protestant Sorbian population - especially in the GDR era - the denominational relationship among the Sorbian speakers in the region has now reversed.

The different development of language behavior in Catholic and Protestant sorbent people is due, on the one hand, to the different structure of the churches. While the Protestant Church is a regional church (the rulers of the Sorbian population were always German-speaking), the Catholic Church has always been transnational in its ultramontane orientation towards the Vatican. The greater closeness to the state of the Protestant Church should have a negative effect on the Sorbian language area, especially with the Germanization policy pursued in Lower Lusatia since the 17th century. On the other hand, the prevailing opinion in the Catholic Church was that the mother tongue should be viewed as a divine gift, which sin should be given up. This explains the extraordinarily close connection between Catholicism and sorbism, which has been emphasized since the end of the 19th century and which continues to this day.

The Catholic parishes today represent the core of the remaining majority area, while in the Protestant areas in the east and north the language has mostly disappeared. While in western Upper Lusatia in particular the centuries-long ties of the Sorbs to the Catholic Church contributed significantly to the preservation of the Sorbian mother tongue, in Lower Lusatia the Protestant church showed no interest in the Sorbian language before and after 1945, despite general promotion of the Sorbs in the GDR to cultivate in church life. Only since 1987 has there been regular Wendish worship again on the initiative of some Lower Sorbers.

Since the second half of the 20th century there has also been a significant proportion of non-denominational Sorbs.

Institutions

Domowina

The central interest group Domowina founded in 1912 (a Sorbian poetic expression for "home", full name Domowina - Zwjazk Łužiskich Serbow z. T. , Domowina - Bund Lausitzer Sorben e.V.) is the umbrella organization of local groups, five regional associations and twelve supraregional Sorbian associations, with a total of approx. 7,300 members, whereby those who are organized in several member associations are also counted several times.

Institute for Sorabistics

On December 10, 1716, six Sorbian theology students founded the “ Wendische Predigercollegium ” (later renamed “Lausitzer Predigergesellschaft”), the first Sorbian association at all, with the permission of the Senate of the University of Leipzig . Their principle was also their greeting: “Soraborum saluti!” Today the Institute for Sorabic Studies at the University of Leipzig is the only institute in Germany where Sorbian teachers and Sorabists are trained. The languages of instruction are Upper and Lower Sorbian. Lately, Sorbian Studies and the courses offered for it at the University of Leipzig have been attracting increasing interest, especially in Slavic countries. The director of the institute has been Eduard Werner (sorb. Edward Wornar) since March 1, 2003 .

Sorbian Institute

Since 1951 there has been a non-university research institute for Sorbian studies in Bautzen, which until 1991 belonged to the German Academy of Sciences in Berlin (East). 1992 to the Sorbian Institute e. V. (Serbski Institut z. T. ) Reorganized, the approx. 25 permanent employees are now working at the two locations Bautzen (Saxony) and Cottbus (Brandenburg). A complex task is to research the Sorbian language (Upper and Lower Sorbian), the history, culture and identity of the Sorbian people in Upper and Lower Lusatia. With its diverse projects, the institute also has an impact on the practice of maintaining and developing Sorbian national substance. Affiliated to it are the Sorbian Central Library and the Sorbian Cultural Archive, which collect, preserve and pass on the Sorbian cultural heritage from almost 500 years.

Domowina publishing house

The Domowina publishing house (Sorb. Ludowe nakładnistwo Domowina ) is also located in Bautzen, and it publishes most of the Sorbian books, newspapers and magazines. The publishing house emerged from VEB Domowina-Verlag, which was founded in 1958 and which was converted into a GmbH in 1990. The publishing house is financed from the budget of the Foundation for the Sorbian People with € 2.9 million (as of 2012). Since 1991 the publisher has operated the Smoler'sche publishing bookstore (Sorb. Smolerjec kniharnja ), which is named after the Sorbian bookstore established in 1851 by the first Sorbian publisher Jan Arnošt Smoler (1816-1884).

Sorbian Museum

The Sorbian Museum in Bautzen (Serbski muzej Budyšin) is located in the salt house of the Ortenburg . In its exhibition there is an overview of the history of the Sorbs from their beginnings in the 6th century to the present day as well as the culture and way of life of the Sorbian population. In regularly changing special exhibitions, works by Sorbian visual artists are presented or special historical topics are dealt with. The district of Bautzen is responsible for the Sorbian Museum . It is also funded by the Foundation for the Sorbian People and the Upper Lusatia-Lower Silesia cultural area .

Foundation for the Sorbian People

The Foundation for the Sorbian People (Załožba za serbski lud) is intended as a joint instrument of the federal government and the two states of Brandenburg and Saxony to support the preservation and development, promotion and dissemination of the Sorbian language, culture and traditions as an expression of the identity of the Sorbian people.

It was founded in 1991 by decree, initially as a non-legal foundation under public law in Lohsa . Taking into account that the Sorbian people do not have a mother state beyond the borders of the FRG and based on the obligation of the Federal Republic towards the Sorbian people stated in the protocol note No. 14 to Article 35 of the Unification Treaty , the material framework conditions were created. With the signing of the State Treaty between the State of Brandenburg and the Free State of Saxony on the establishment of the Foundation for the Sorbian People on August 28, 1998, the Foundation acquired its legal capacity. At the same time, a first financing agreement, valid until the end of 2007, was agreed between the federal government and the states of Brandenburg and Saxony. On the basis of the second agreement on joint financing of July 10, 2009, the foundation receives annual grants from the Free State of Saxony, the State of Brandenburg and the federal government in order to fulfill its purpose. The agreement is valid until December 31, 2013.

The grant amount set up until 2013 was 16.8 million euros. It was made up as follows: Federal Government 8.2 million euros, Saxony 5.85 million euros, Brandenburg 2.77 million euros. The Sorbian National Ensemble (29%), Domowina-Verlag (17.2%) and the Sorbian Institute (11.3%) as well as the foundation administration (11.4%) received the largest share of the foundation's budget. There are repeated public controversies about the absolute amount of funding and the distribution for individual institutions and projects, which in some cases led to demonstrations.

Schools and kindergartens

In the Free State of Saxony and Brandenburg there are several bilingual Sorbian-German schools in the bilingual Sorbian settlement area, as well as other schools where Sorbian is taught as a foreign language. In Saxony, eight primary and six secondary schools worked bilingual in the 2013/14 school year, and four primary and one secondary schools with elementary school in Brandenburg were bilingual Sorbian-German schools. The Sorbian grammar school in Bautzen and the Lower Sorbian grammar school in Cottbus make it possible to obtain the higher education entrance qualification in Sorbian .

There are still several Sorbian kindergartens in both federal states. The cross-state Sorbian School Association has also launched the Witaj project for bilingual care and training at kindergartens and schools, in which the children are introduced to the Sorbian language by immersion .

See also: Sorbian school system

media

An Upper Sorbian daily newspaper Serbske Nowiny (Sorbian newspaper), a Lower Sorbian weekly newspaper Nowy Casnik (Neue Zeitung), the Sorbian cultural monthly Rozhlad (Umschau), the children's magazine Płomjo (Flamme), the Catholic magazine Katolski Posoł and the Protestant church newspaper Pomhaj Bóh appear . The Sorbian Institute publishes the scientific journal Lětopis every six months . For educators there is the trade journal Serbska šula .

There is also the Sorbian Broadcasting , whose program is produced by the Central German Broadcasting and Broadcasting Berlin-Brandenburg . Radio broadcasts in Sorbian-language are broadcast for a few hours every day from stations in Calau (RBB) and Hoyerswerda (MDR 1), and all of the RBB's Lower Sorbian broadcasts can also be listened to on the Internet. For young people, the RBB broadcasts the half-hour monthly magazine Bubak every first Thursday of the month and the MDR broadcasts the two-hour weekly radio Satkula every Monday .

Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg has been producing the half-hour Lower Sorbian television magazine Łužyca (Lausitz) every month since April 1992 , and MDR has been producing the half-hour Upper Sorbian program Wuhladko (prospect) every month since September 8, 2001 . In addition, the MDR broadcasts Our Sandman every Sunday in two-channel sound .

Culture

literature

Until the late Middle Ages there was only oral tradition of legends, fairy tales, magic spells, proverbs and the like.

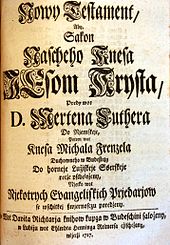

With the Reformation, writing began in Lower and Upper Sorbian. Mikławš Jakubica completed the translation of the New Testament into Lower Sorbian as a manuscript in 1548 , but could not have it printed. The first printed work in Lower Sorbian was Martin Luther's hymn book in the translation by Albin Moller (1574), in Upper Sorbian Luther's Small Catechism (1597).

It was not until the 19th century that nationally conscious Sorbian literature emerged . Until then, the written and printed Sorbian literature was almost exclusively limited to religious and economic content. The poet Handrij Zejler is considered to be the founder of modern literature and in 1847 co-founded the Sorbian scientific society Maćica Serbska . His poem "Na sersku Łužicu" ( "To the Sorbian Lusatia" ), published in 1827, was set to music by Korla Awgust Kocor in 1845 , from which the today's hymn of the Sorbs " Rjana Łužica " ( "Beautiful Lusatia" ) originated. Other classical poets on the Upper Sorbian side were the song and fairy tale collector Jan Arnošt Smoler and the Catholic priest and poet Jakub Bart-Ćišinski . In the Sorbian literature dominated by Upper Sorbian, the poet Mina Witkojc made a significant contribution to the Lower Sorbian spoken in Lower Lusatia.

The literary versions of the Krabat saga , Mišter Krabat (1954) by Měrćin Nowak-Njechorński , The Black Mill (1968) by Jurij Brězan and Krabat (1971) by the Sudeten German writer Otfried Preußler have been translated into many languages and contributed to the Sorbs in the To publicize abroad.

Current authors include Jurij Brězan , Kito Lorenc , Jurij Koch , Angela Stachowa , Róža Domašcyna , Jan Cyž , Benedikt Dyrlich , Marja Krawcec and Marja Młynkowa .

Visual arts

The first artists to appear in the Baroque era were the sculptors Jakub Delenka (1695–1763) and Maćij Wjacław Jakula (Jäckel) . Jäckel had a workshop in Prague and created several sculptures for Bohemian monastery churches and Prague's Charles Bridge . Among the outstanding artists of the 18./19. In the 19th century the landscape draftsman and eraser Hendrich Božidar Wjela , who studied between 1793 and 1799 at the Dresden Art Academy with Johann Christian Klengel and Giovanni Battista Casanova . As a draftsman and eraser, Wjela can be classified between Sturm und Drang and Romanticism.

At the end of the 19th century, the rise in folklore and homeland security gave rise to so-called traditional painting and the interest of German and foreign artists in the Sorbs was aroused. Artists such as William Krause , Ludvík Kuba and later Friedrich Krause-Osten , among others, dedicated themselves to the rural people with this painting aimed at a descriptive representation of folklore , and showed the Sorbs in their cultural diversity and tradition.

The painter, graphic artist and writer Měrćin Nowak-Njechorński as well as Hanka Krawcec and Fryco Latk are among the outstanding Sorbian artists of the 20th century . In the twenties, artists tried not to interpret national ideals simply by portraying folklore, but rather through greater aesthetic and philosophical penetration into the idiosyncrasies of the Sorbian people. After the Second World War, Sorbian painters and graphic artists came together in 1948 to form the working group of Sorbian visual artists . The working group was headed from 1948 to 1951 by Conrad Felixmüller , whose folkloric painting from the rural milieu of the Sorbian Upper Lusatia reflects a rediscovery of his Sorbian ancestors. The Sorbian working group also included Horst Šlosar and Ota Garten . Contemporary Sorbian artists include the painters Jan Buk and Božena Nawka-Kunysz as well as the graphic artist and ceramist Jěwa Wórša Lanzyna .

See also: List of Sorbian visual artists

music

The early Sorbian music is characterized by the folk song and the instrumental folk music, which was passed down orally for centuries and which was also newly created.

16th to 18th century

At the time of the Reformation there were some well-known Sorbian church musicians , such as Jan Krygaŕ ( Johann Crüger ) , the cantor of the St. Nicolai Church in Berlin, who came from Lower Lusatia . He is considered the most important Protestant choral composer and music theorist of the 17th century, from whose writings even Johann Sebastian Bach acquired his musical craft.

The first secular work of Sorbian art music comes from Jurij Rak from the year 1767. It is a "jubilee mode" of the then law student for the 50th anniversary of the Wendish Preachers College in Leipzig ("Sorabia").

19th and early 20th centuries

There are first documentations of Sorbian folk music from the early 19th century, such as the “Kral's violin book” by folk musician Mikławš Kral (1791–1812) and the collection “Folk songs of the Sorbs in Upper and Lower Lusatia” by Leopold Haupt, published in Bautzen (1797–1883) and Jan Arnošt Smoler .

Although the Sorbian musical life had neither a theater nor an orchestra, art music reached its first significant climax in the middle to the end of the 19th century. The teacher and cantor Korla Awgust Kocor played a decisive role . Together with the poet Handrij Zejler, he organized a first song festival on October 17, 1845 in the Bautzener Schützenhaus. Zejler's Rjana Łužica was performed there for the first time, the setting of which was done by Kocor. They established the tradition of the Sorbian song festivals, which developed into popular events in the Upper Lusatian cultural area. One of the most important works by Kocor is the oratorio "Nalěćo" (German spring ) based on a cycle of poems by Zejler.

Around 1900 Jurij Pilk was one of the leading representatives of the Sorbian musical life. The overture to the Singspiel “Smjertnica” (The Goddess of Death) is one of his most important works. Another personality with lasting influence was the Sorbian composer, music teacher and editor of music literature Bjarnat Krawc .

1945 to 1990

After 1945 Jurij Winar (1909–1991) was the driving force behind the revival of Sorbian musical life. Winar founded today's Sorbian National Ensemble ( Serbski ludowy ansambl , SLA) in 1952 , where he was artistic director and artistic director until 1960. Supported by the Foundation for the Sorbian People , the three professional branches of ballet , choir and orchestra cultivate, preserve and develop the cultural tradition of the Sorbs today .

presence

Representatives of contemporary Sorbian classical music include Ulrich Pogoda , Jan Bulank , Detlef Kobjela , Sebastian Elikowski-Winkler and other composers.

Since the 1990s there have been an increasing number of musicians and groups who, in addition to folk music, also played or play pop, rock, metal and punk in Upper and Lower Sorbian, such as Awful Noise , DeyziDoxs , die Folksamen , Berlinska Dróha , Jankahanka , Bernd Pittkunings and other.

theatre

The German-Sorbian People's Theater (Němsko-Serbske ludowe dźiwadło) goes back to the Bautzen Theater, which had existed since the end of the 18th century, and which was merged in 1963 with the Sorbian People's Theater, which had existed since 1948. It performs works in German and Sorbian. The theater in Bautzen is a municipal run by the district of Bautzen and is partly financed from funds from the Foundation for the Sorbian People and the Upper Lusatia-Lower Silesia cultural area .

folklore

Many customs have been preserved, especially the Easter riding , the bird wedding and the traditional painting of Easter eggs . Numerous Slavic mythological ideas are still alive today, such as the midday woman (Připołdnica / Přezpołdnica), the Aquarius (Wódny muž), the lamentation of God (Bože sadleško) or the dragon that brings money and luck (obersorb. Zmij , niedersorb. Plón ).

In the Upper Sorbian core area, roughly described by a triangle between the cities of Bautzen , Kamenz and Wittichenau , crucifixes on the wayside and in front gardens as well as well-tended churches and chapels are an expression of a (mostly Catholic) popular piety that has been lived up to the present day , which does much to preserve Sorbian Substance contributed.

The Sorbian costumes are very different from region to region. Some older women still wear them every day, but younger women only wear them on major holidays, such as the bridesmaid's costume (družka) on Corpus Christi .

Easter rider in the monastery of St. Marienstern

Sorbian festival costume from the Spreewald

history

Early Sorbian history (6th to 9th centuries)

The Sorbs can look back on a traceable history of around 1400 years. In the first half of the 6th century AD, their ancestors left their residential areas north of the Carpathians between Oder and Dnepr as part of the migration of the peoples at that time and moved to the west via Silesia and Bohemia , where in the 6th century they occupied the area between the upper reaches of the Neisse in northern Bohemia and the river basin of the Saale with the Saxon foreland of the Ore Mountains and the Fläming . These areas have been almost uninhabited since the emigration of Germanic peoples in the course of the migration , the remaining Germanic population was assimilated.

In the so-called Fredegar -Chronik be for 631/32 Wenden and first sorbent mentioned that repeated looting in Thuringia and other districts of the Kingdom of the Franks invaded: "Since then fell Apply repeatedly in Thuringia and other pagi one of the Frankish Empire to strip them; yes even Dervanus , the dux of the people of the Sorbs [lat. Dervanus dux gente Surbiorum], who were of Slavic origin and had always belonged to the kingdom of the Franks, submitted with his people to the kingdom of Samos . ” After further attacks by the renegade Sorbs, Duke Radulf, who ruled Thuringia , was given an important one Sieg 634/635 master of the situation and in 641 concluded an alliance with the neighboring Slavic tribes on the basis of equality.

The West Slavic tribes referred to in the sources of the early and high Middle Ages as "Sorbs" (lat. Surbi, sorabi ), inhabitants of the areas between Saale and Mulde , became increasingly dependent on the (east) Franconian empire in the 8th and 9th centuries and the Limes Sorabicus border and protection zone was created in this area. For the year 806 it is documented that a Sorbian king named Miliduch (or Melito) was killed, whereupon other kings submitted, sometimes after bitter fighting. They were forced to pay tribute, converted to the Christian faith and assimilated by the medieval German East Settlement . The Franconian historical sources provide only sparse information about the Daleminzians who live further east in the Elbe valley and the Slavic tribes of the Lusitzi (also Lusici , Lusizer or Lausitzers ) and Milzener , whose descendants now bear the name "Sorbs". While some historians (u. A. Karlheinz Blaschke , Joachim Herrmann ) assume the that Ethnonym sorbent until the early Middle Ages from the Saale River and dump to the east living and similar dialects speaking tribes during spreading, the Sorabist represented Hinc Schuster SEWC on based on linguistic considerations, the thesis that all Sorbian-speaking tribes already had this common (super) name at the time of their immigration. The differentiation into individual groups with their own names only began in their new home.

While in Bohemia and Moravia the first empires were formed in the late 7th century and more stable early feudal state structures emerged from the 9th century, the Slavs between Saale and Neisse did not have any supraregional political structures known today at the time of the conquest by the Franks . The Slavs lived primarily as farmers in small tribal associations, each of which only comprised a few dozen rather small village settlements. The society of the Western Slavs was clearly divided into the mass of dependent peasants and a narrow aristocratic ruling class. From the latter, the tribal or Gau princes were recruited, who in the Franconian sources are usually called dux (= duke, prince).

The centers of rulership were probably the numerous Slavic castles with defensive walls made of wood and earth, which were built from the end of the 9th century. Depending on the location, hilltop castles were built on sites that towered over the surrounding area, which, depending on the building material available at the site, could also have mighty stone walls (e.g. on the Landeskrone near Görlitz). If there were no suitable altitudes, low- rise castles were usually built with bodies of water or swamp landscapes (swamp ring walls or swamp castles ) as natural protection. According to the list of the Bavarian geographer , the Sorbs had 50 and the Lusitzi and Milzener 30 civitates each . The term civitas probably denotes a central castle or a castle district with associated settlements. The localization of the settlement area of the Sorbs or surbi according to the information of the Bavarian geographer remains controversial in research. The core area of today's Sorbian settlement of Upper Lusatia lies in the tribal area of the Milzener with their main castle Budissin ( Bautzen ). The settlement area of the Lower Lusatian Sorbs corresponds to that of the Slavic tribe of the Lusitzi, which gave the landscape its name.

Little is known about the pre-Christian religion of the Slavs between Saale and Neisse. It is neither known whether there was a priesthood, nor have the archaeologists in these areas discovered a sanctuary of supraregional importance. According to medieval tradition, however, some early Christian churches were built in place of old Slavic shrines, for example the church on the sacrificial mountain in Leipzig-Wahren .

Up until the beginning of the 10th century, the Sorbian-settled areas on the Saale were only more or less dependent on the Franconian Empire. The Slavs in the Limes Sorabicus area had to pay tributes to the Franks. A more intensive German-speaking settlement and rule building did not come about until King Heinrich I.

The Sorbs in the High Middle Ages (10th to 11th centuries)

After Henry I had concluded a nine-year armistice with the Hungarians around 924–926, he began to expand his power on the eastern border of the empire. In 928/929 he led a large-scale successful campaign to subjugate the Slavic tribes east of the Elbe ( Obodriten , Wilzen , Heveller , Daleminzier and Redarians ). The king secured his advance by building numerous castles. One of the most important foundations was the Zwingburg in Meißen (on the site of today's Albrechtsburg ) in 928/929 against the defeated Daleminzier, from where he subjugated the Milzener in 932 . Through further victories in 932 over the Lusizi - in the process he destroyed their tribal castle Liubusua - and in 934 against the Ukranians, he also forced these Slavic tribes to pay tribute.

At the beginning of the early modern period, the common name Sorbs was gradually transferred to the settling Lusitzi and Milzener, who were still clearly separated from the Sorbs in the early and high medieval sources. The German term Wenden, which from the beginning had been a generic term for the Slavic peoples living east of the old imperial border, remained more important until the 19th century. In linguistics today, the languages of the southern Elbe Slavs or their surviving remnants are generally referred to as Sorbian.

Gero , the margrave of the Saxon East Marks appointed by Emperor Otto I in 939 (it comprised the entire area between the Elbe, Havel and Saale) continued the violent subjugation of the Sorbs. In 939 he invited 30 Slavic princes to a feast and had them murdered. The bloody act resulted in a revolt by the Slavs, which was also joined by tribes north of the Ostmark. In several campaigns from 954 to Gero's death in 965, Emperor Otto I and Gero defeated the north-west Slavic tribes and the Lusitzi in Lusatia, which extended and strengthened the Saxon tributary rule as far as the Oder. While the Slavs in what is now northern Brandenburg and Mecklenburg were able to regain their independence for a longer period of time through a major uprising in 983 , the submission of the Sorbs was final. The rule over the Lausitz and the Milzenerland with the strategically important Bautzen Castle was fought over from 1002 to 1032 with mutual success between the Germans and the Polish Duke Bolesław Chrobry . The investigation of 25 so-called ring walls in Niederlausitz could very well show a correspondence between the heyday of castle building at the beginning of the 10th century and Otto I's conquering activities. The construction activities end around 960–970 and are probably due to the subjugation of Lausitz by Gero 963.

In the 10th century, the Christian Church began proselytizing among the Slavs in the Elbe-Saale area and in Lusatia. The consolidation of German rule and the creation of church structures went hand in hand. Emperor Otto I founded the Archdiocese of Magdeburg in 968 with the suffrage of Brandenburg, Havelberg, Zeitz, Merseburg and Meißen. The Sorbs, Milzener and Lusizer had the Bishop of Meissen tithes paid. At the same time, under the margraves of the Sorbian populated areas - the great Mark Geros had been subdivided into several smaller territories after his death ( Nordmark , Mark Lausitz , Mark Meißen , Mark Zeitz and Mark Merseburg ) - the establishment of Burgwarden . The subject areas were given to German nobles as fiefs , the new masters built castles and received taxes from the associated Slavic villages. In some cases, the German nobility only succeeded the Sorbian tribal princes. The former Slavic ruling class had been decimated by the previous wars and what was left of them were pushed into subordinate positions. The bulk of the Sorbian peasant population were middle landowners without hereditary property rights, as well as impoverished peasants or serfs without rights . They had to pay dues to the feudal lords as well as hand services, to which the tithing came for the church. The upper stratum of the peasants was made up of the village chiefs ( Župane or Supane ) as well as soldiers and servants.

12th to 15th centuries

After the numerous wars of the 10th and the beginning of the 11th centuries, the integration of the Sorbian settlement area into the empire proceeded in a peaceful manner in the following period. The king, the margraves and, last but not least, the ecclesiastical institutions promoted the so-called state development . The phase of high colonization extended from around 1150 to 1300 and was mainly carried by German settlers who came from Flanders, the Netherlands, Saxony, Franconia, Thuringia and the Rhineland, among others. The old-established Sorbian inhabitants were mostly not expelled, rather the new German villages almost always arose on cleared land. The existing Slavic settlements were expanded in places that were already populated. A first phase of early colonization , with a considerable proportion by old Slavic settlers, existed as early as 1100, for example around Gera , Zeitz and Altenburg in the Pleißenland .

In the Lusatia, too, the clearing in the first half of the 12th century was mainly carried out by Sorbian farmers. During this time z. B. many new places in the area around Hoyerswerda , Spremberg and Weißwasser . The expansion of the cultivated land enlarged and stabilized the Sorbian language area in this area. In some areas, for example around the Cistercian convent of St. Marienstern and near Hoyerswerda, the Sorbian element was so strong that some German-speaking local foundations were Slavicized over time. B. in Dörgenhausen (Sorb. Němcy) . Under the Bohemian kings, the expansion of the state in Upper Lusatia intensified in the middle of the 12th century, and the kings and the Meissen bishops practiced it in competition. German farmers cleared large forest areas in the south and east of the country and created numerous new villages, for example around Bischofswerda and Ortrand . In Lower Lusatia, the German settlers settled in the western, northern and eastern peripheral areas. B. Luckau , Storkow and Beeskow as well as Sorau in today's Poland.

In contrast to the Old Sorbian settlements, the immigrants were able to set up their settlements under Flemish, Dutch or Franconian law (the designation German law only emerged later), received inheritance rights on the developed land and were personally free. Because the aristocratic territories only gained value through clearing and cultivation, the immigrant Germans only had to pay lower taxes to the landlords and perform few services for them, or were completely exempt from these for the first few years. Insofar as Sorbian farmers were involved in the development of the country, they mostly enjoyed the same rights as the German colonists.

In the course of the country's expansion, the increase in population and the influx of German merchants and craftsmen, numerous cities were founded. Mainly at crossings of important trade routes, at existing market settlements and around castles or margrave seats. From the end of the 12th century the first town charter was granted, for example. B. west of the Elbe at Leipzig (1165) and Meißen (around 1200) and east at Lübben and Cottbus (each around 1220) in Niederlausitz and Löbau (1221), Kamenz (1225) or Bautzen (1240) in Upper Lusatia. West of the Elbe, German settlers quickly became overweight and the displacement of the Sorbian language was largely complete in the 14th century. These changes are expressed in the restriction of the use of the Sorbian language in court, as for example in the Sachsenspiegel at the beginning of the 13th century - whoever was demonstrably able to speak German had to use it - or in a decree in the Principality of Anhalt from 1293, the forbade the use of Wendish as the language of court . These restrictions are not seen primarily as an expression of nationalist attitudes, but rather as an adaptation to the prevailing circumstances.

In the 14./15. In the 19th century, the Sorbs made up about half of the rural population in Upper Lusatia and the proportion was significantly higher in Lower Lusatia. In the cities their share was usually lower and varied considerably. In Bautzen it was around 35%, in Cottbus almost 30%, in Guben, Löbau and Bischofswerda it was considerably lower. In Luckau it was 50% and Calau had almost exclusively Sorbian residents. From the first half of the 14th century there was increased Sorbian immigration in the cities of Lusatia, as evidenced by numerous Sorbian citizens' journeys, for example from Luckau, Senftenberg or Bautzen. As the dynamic economic development came to an end, there was also an increasing negative attitude towards the Sorbian population groups. This is evidenced by the “German ordinances” z. B. from Beeskow (1353), Luckau (1384), Cottbus (1405), Löbau (1448) or Lübben (1452), whereby Sorbs were temporarily denied access to the guilds - mainly for reasons of competition . In the 16th century, many of these restrictions were lifted by the guilds and by decision of the margraves.

16th to 18th century

Reformation and the Thirty Years War

At the beginning of the 16th century, the Sorbian settlement area had shrunk further, mainly due to the assimilation of the Sorbs and the accompanying displacement of the language from the west. Apart from a few remaining larger linguistic islands around Wittenberg , Eilenburg and Meißen , the closed Sorbian language area now only extended over the Lusatia with an area of around 16,000 km². Around 195,000 people lived there, the vast majority of whom (160,000) were Sorbs. To the north-east of Guben and Sorau, the Sorbian-speaking area still had a direct connection to the Polish-speaking area around 1600. It was not until the devastation of the Thirty Years' War and the associated losses of the Sorbian population as well as a targeted Germanization policy supported by the Protestant Church that the Sorbian area became an island surrounded by German-speaking regions in the second half of the 17th century.

Large parts of the Lusatia belonged to the Bohemian kings from the House of Habsburg as secondary countries until 1635 . The lordship of Cottbus as well as lordship from Zossen to Beeskow and Crossen to the north were owned by the Hohenzollern family . The Wettins owned the German-Sorbian mixed zone in the Saxon-Meissnian area west of the Lusatia . For all three ruling houses these were peripheral areas and the Habsburgs in particular did not exercise strong central power. Administration was left to the estates, which, due to the poor economic situation of the nobility at the beginning of the 16th century, led to increased exploitation of the rural areas. The demand for full national services (six days a week work on the lordly estates, from sunrise to sunset) led to locally limited peasant unrest in Reichwalde ( Muskau rulership ), Lieberose and Hoyerswerda, and in 1548 to the peasant uprising of Uckro in the vicinity from Luckau.

The unrest was not related to the Reformation initiated by Martin Luther in Wittenberg in 1517 , which penetrated the two Lusatia and thus the Sorbian settlement area with a delay. The Catholic Habsburgs tried to stop the Reformation in the Lausitz, but could not prevail against the evangelically-minded estates, cities and knighthoods. The estates took church sovereignty into their own hands and gradually introduced the Reformation into the individual rulers until around the middle of the 16th century. All Sorbs in Lower Lusatia and more than three quarters of the Upper Lusatian Sorbs were Protestant in the middle of the 16th century. Only the Sorbs in the possessions of the St. Marienstern Monastery and the Bautzen Cathedral Monastery of St. Petri remained predominantly Catholic.

There was initially an active Reformation movement in the predominantly German-speaking cities. Reformation literature hardly found its way into the rural areas because most of the Sorbs at that time could neither understand German nor read or write. As a result, the service for the Protestant Sorbs was now carried out in their mother tongue. Sorbs were also keen advocates of the Lutheran ideas of the Reformation, the best-known among them was the theologian Jan Brězan (Johann Briesmann) from Cottbus. From the middle of the 16th century onwards, other Sorbian Protestant clergymen, taking up the Reformation principle of preaching in their mother tongue, began to create a Sorbian religious literature by translating the core works of Protestantism, the Bible, catechism and hymns, from German. In 1548, Mikławš Jakubica from the Sorau reign translated Luther's New Testament, which was the first ever translation of the Bible into Sorbian. However, it was never printed due to a lack of financial resources. In 1574, Luther's catechism, combined with a hymn book, appeared in the Lower Sorbian translation of Albin Moller from Straupitz , and in 1595 Wjaclaw Warichius published Luther's catechism in Upper Sorbian from Göda .

From 1538 the estates in Upper Lusatia promoted Sorbian theology students and by 1546 40 studied at the University of Wittenberg and by 1600 147 Sorbs had completed their theology studies there. At that time, Sorbian clergymen were trained at the Brandenburg State University Viadrina in Frankfurt and Sorbian language exercises were held until 1656, which were the first Sorbian courses at a university.

The devastation of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) interrupted the first flowering of Sorbian education and literature for many decades. Like many other regions in Germany, the Lausitz region was hit several times by the passage of large armies and epidemics that claimed thousands of lives. According to conservative estimates, the population loss was over 50% and in the eastern part of the Sorbian settlement area around Sorau and Liebenwerda over 75%, where many places were almost deserted at the end of the war. These areas on the Neisse and east of it were later repopulated by Germans, which made the closed Sorbian area much smaller again.

From the Peace of Prague to the end of the 18th century

In 1635, before the end of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), the two margravate Lower and Upper Lusatia of Bohemia came to the Electorate of Saxony with the Peace of Prague , with the exception of Cottbus with the Peitz fortress in the center of Lower Lusatia , which had belonged to the Hohenzollern family since the middle of the 15th century and thus to the Brandenburg and later Prussian domain. The change of ownership of the two Lusatia initially changed little in terms of their autonomy, as the new sovereign in the traditional recession had to promise the retention of the class privileges, the feudal sovereignty of the Bohemian crown and the ecclesiastical-denominational institutions in their existence. This special status initially prevented the influence of state centralization efforts and, on the one hand, favored the strengthening of the Sorbian culture and language development, but on the other hand led to the consolidation of the positions of the local nobility and their power over the peasant population. Amplified by the onset of the transition from the natural economy to Gutswirtschaft, hereditary property in unerblichen land (Let property) was converted and the farmers to stringent compulsory labor forced into the developing Ritter goods. Through the subordinate orders issued in 1651 in the Saxon parts of Lausitz and in 1653 in the Brandenburg parts of Niederlausitz, the peasants were bound to the owner of the manor by inheritance (Schollenzwang) and they themselves, as well as their children, were subjected to servants .

On the one hand, this led to a strong rural exodus of the rural population. According to estimates, between 1631 and 1720 more than 8,000 fron farmers left their manors in Upper Lusatia alone. On the other hand, there were bitter acts of resistance through petitions, petitions, refusal of services and taxes, and even armed uprisings. The peasant unrest, which often encompassed several villages, usually lasted for several years and was ultimately put down by the deployment of the military. In 1667/68, for example, around 5,000 peasants rose up in the Cottbus district and it was only through the mobilization of 800 soldiers that the uprising was brought under control. Again in Cottbus there was the biggest uprising of Sorbian and German farmers from 1715 to 1717, in which over 50 villages took part under the leadership of the Eichow village mayor Hanzo Lehmann .

With the development of absolutism , which developed more strongly in the Brandenburg regions of the Hohenzollern than in Saxony, the Sorbs began to be integrated into the organized state and thus the Sorbian language was displaced. Due to the different political objectives, the approach to Sorbian differed from sovereign to sovereign. Christian I of Saxony-Merseburg in Lower Lusatia and the Brandenburg Elector Friedrich Wilhelm in the Wendish district of the Kurmark acted most intensively against the Sorbian. Sorbian books and manuscripts were confiscated and the spread of German in school lessons and at church services was promoted. In the course of the 18th century, the Sorbian church services that had been held since the Reformation were abolished in most parishes in Lower Lusatia, although most of the parishes affected were almost exclusively monolingual Sorbian at that time. Schools also became a major factor in Germanization, as Sorbian was only used as an auxiliary language in the first grades, where it was necessary, but otherwise only German was taught and spoken. In Upper Lusatia, where the estates were able to maintain their autonomy , a moderate stance towards the Sorbian language was adopted, also for fear of a revival of Catholicism, as happened for example in the neighboring Duchy of Sagan or in Wittichenau , and a moderate stance towards the Sorbian language was adopted in the Cottbus district by Frederick I even rural school system founded on the basis of the Sorbian language and promoted religious Sorbian Schriftentum. The background here was the avoidance of internal conflicts as the basis for expansion efforts to the east.

Further development of the Sorbian literature

After the first beginnings of Sorbian religious literature in the middle of the 16th century, despite all the political and economic difficulties after the Thirty Years' War, Sorbian literature flourished and the Sorbian language was consolidated. The strongest cultural activity was after the war on the northern edge of the Sorbian settlement area, building on and inspired by the early work of the translator and philologist Handroš Tara (Andreas Tharaeus, 1570–1640), pastor from Friedersdorf in the Storkow office. In 1650, the first Sorbian grammar was written by the Lübbenau pastor Johannes Choinan , which was distributed in numerous copies. Around this time, the first Sorbian primer by Juro Ermelius , Rector of the Calau City School, as well as four religious Sorbian pamphlets from 1653 to 1656, produced by several clergymen, mainly from the Beeskow office, appeared . As a result of the measures taken to displace the Sorbian in Lower Lusatia and the Wendish district of the Kurmark, the area lost its importance for the further cultural development of the Sorbs and at the turn of the 18th century it was replaced by the Cottbus district and Upper Lusatia.

The clergyman Jan Bogumil Fabricius, trained in Halle and influenced by Pietism , worked in the Cottbus district . He was not a Sorbe himself, but learned the Sorbian language in a very short time and with his works published in 1706 (Catechism) and 1709 (New Testament), financially supported by Frederick I , laid the foundation for the written language of Lower Sorbian . Fabricius later rose to become the highest ecclesiastical dignitary in the district, became pastor of the city of Peitz and finally church inspector of Cottbus. Between 1706 and 1806 45 books in Lower Sorbian appeared in the Cottbus district, including the translation of the Old Testament by Jan Bjedrich Fryco .

In Upper Lusatia, leading representatives of the Pietist movement campaigned for the dissemination of religious literature in the vernacular. At the same time, the competition between denominations led to a competition in the editing of books in order to expand and maintain the area of one's own denomination. On the Protestant side, Michał Frencel (1628–1706), pastor in Großpostwitz near Bautzen, published the New Testament in 1706 , in the dialect as it was spoken in his community, thus establishing the Upper Sorbian written language . His son Abraham Frencel (1656–1740) later continued his work. From 1688 to 1707 the entire Bible was translated for the first time by the Roman Catholic clergyman Jurij Hawštyn Swětlik (1650–1729) - his version, however, remained unprinted - and thus created the Catholic version of the Upper Sorbian written language. In the years from 1688 to 1728 alone, 31 book titles appeared in the Sorbian language in Upper Lusatia, some with financial support from the estates.

While the development of culture was initially mainly carried out by individuals, the first institutions emerged from the beginning of the 18th century that were dedicated to the promotion and development of the Sorbian language, culture and education. In 1724 the Catholic Wendish seminary was founded in Prague as a training center for Catholic priests from Upper Lusatia. Among the students was Franc Jurij Lok , who later became dean of the Catholic chapter of St. Petri in Bautzen (1796–1831), and who successfully advocated popular education for the Sorbs. By students of Protestant theology was in 1716 at the University of Leipzig, the Wendische preacher College and in 1746 in Wittenberg , the Wendish Preachers Society of Wittenberg launched. The Lipske nowizny a wšitkizny was also published in Leipzig in 1766 . Sorbian and German scholars founded the Upper Lusatian Society of Sciences in Görlitz in 1779 , which reflected the German-Sorbian reciprocity under the sign of the Enlightenment . Georg Körner , a member of the Wendish Preachers' College, was the first German to deal intensively with the Sorbian language and in 1767 published the philological-critical treatise on the Wendish language and its use in science, as well as a Sorbian-German dictionary in 1768.

19th century

Shortly before the end of the 18th century, between 1790 and 1794, under the influence of the French Revolution , there were major peasant unrest in both Lusatia, which in parts of Upper Lusatia was triggered directly by the great Saxon peasant uprising of 1790 . At the turn of the 19th century, the Sorbian settlement area was the scene of the Napoleonic Wars . In addition to repeated large troop marches, from which the population of all parts of the Lusatia suffered, the battle of Bautzen and further battles near Luckau and Hoyerswerda occurred in 1813 during the wars of liberation . With the end of the war and the Congress of Vienna in 1815, there was a territorial reorganization of Europe, which also affected large parts of the Sorbian settlement area. The areas of Lower Lusatia, which formerly belonged to the Kingdom of Saxony, and the northern and eastern Upper Lusatia around Hoyerswerda, Weißwasser and Görlitz fell to Prussia. As a result, the Sorbian settlement area, which until then administratively still largely belonged together, which at the end of the 18th century only comprised about 7,000 km², was divided and with 200,000 Sorbs the majority of the Sorbian population now belonged to Prussia. At that time there were still 50,000 Sorbs living in the remaining Saxon part of Upper Lusatia.

Due to the separation of the Sorbian population into two states and the fact that the Sorbs were now in the minority in almost all government districts due to the reorganization in Prussia, the intellectual and cultural development, especially in Lower Lusatia, was adversely affected and the formation of one's own Nation made nearly impossible. The suppression of the Sorbian language in Prussia was further intensified and reached a climax in the second half of the 19th century after the founding of the empire . Due to the tense German-Russian relationship at that time, the existence of a Slavic national minority was seen as a threat to Germany. With the approval of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck , a phase of anti-Sorbian repression was initiated in the German Reich . In the Prussian part of Upper Lusatia there was a general ban on the Sorbian language in schools in 1875, in 1885 the Sorbian confirmation classes were banned in Silesia and in 1888 the Prussian Ministry of Education banned Sorbian language classes at the Cottbus grammar school . Sorbian intellectuals reacted to these attacks and tried to increase resistance against the Sorbian policy, but the assimilation of the Lower Lusatian Sorbs accelerated considerably under the increased pressure of the authorities towards the end of the 19th century.

The 19th century was also a heyday of bourgeois Sorbian culture, which was largely supported by individual Upper Sorbian personalities. The linguists and publishers Jan Pětr Jordan and Jan Arnošt Smoler were advocates of the national movements of the Slavic peoples and their cultural reciprocity. They endeavored to reform the Sorbian spelling, which should bring the previous very inconsistent spelling into line with that of other Slavic peoples and which was seen as an essential condition for the development of a uniform Sorbian literature. Jordan was also significantly involved in the preparation and implementation of the Slavs Congress in Prague, which was held in June 1848 , in which a Sorbian delegation also took part and where the Pan-Slavic colors were determined, on which the Sorbs' flag is based. Together with Joachim Leopold Haupt (1797–1883) and Handrij Zejler, Smoler brought together the important Sorbian song collection “The folk songs of the Wends in Upper and Lower Lusatia”. The poet Handrij Zejler is considered to be the founder of modern Sorbian literature as well as himself as the driving force and his works as the culmination of the Sorbian national revival , which includes the Sorbian literary development of the 18th and 19th centuries. "Since Zejler excluded the possibility of a Sorbian nation state, for him the national emancipation of the Sorbs was synonymous with advocating the establishment of a Sorbian bourgeois identity within a German state" , which in his opinion would secure the existence of the Sorbian people. Another outstanding personality of this time was the Sorbian composer Korla Awgust Kocor , who was a friend of Zejler . From 1845 both organized Sorbian singing festivals, which left a lasting impression on the Upper Sorbian population and contributed to the consolidation of the Sorbian language and culture.

In 1847 the scientific society Maćica Serbska was founded in Bautzen , which represented the climax of the development of the intellectual and cultural Sorbian life in the Vormärz . The founding members included Smoler and Zejler and Maćica Serbska quickly developed into the center of Sorbian scientific and cultural endeavors; it is the oldest still existing Sorbian association. The Sorbian scientist Arnošt Muka , also a member of Maćica Serbska , examined the state of the Sorbian language and culture in Upper and Lower Lusatia on extensive trips between 1880 and 1884 and then published his Statistika Łužiskich Serbow ("Statistics of the Lusatian Sorbs") . According to Muka, there were 160,000 Sorbs at that time, who still made up the majority of the population in large parts of northern Upper Lusatia and Lower Lusatia.

20th and 21st centuries

In 1904 the Wendish House (Serbski dom) opened its doors on Lauengraben in Bautzen . On October 12, 1912, the umbrella organization of the 31 Sorbian associations, the Domowina , was founded in Hoyerswerda . It brought together the citizens ', farmers' and educational associations that were established after 1848/49 with around 2,000 members and was intended to further consolidate Sorbian cultural life.

Weimar Republic

After the end of the First World War, there were calls for independent administration. The Weimar Constitution only stipulated in Article 113 that the "foreign-language parts of the Reich [...] are not impaired in their free popular development by the legislation and administration, especially not in the use of their mother tongue in teaching, as well as in internal administration and the administration of justice " allowed to.

In 1920 the Wendish People's Party was founded by Jan Skala , but could not win any seats in parliament. She campaigned for the goals of the Sorbian national movement. Together with the Domowina and the scientific association Maćica Serbska they formed the Wendish People's Council in 1925. The Sorbs also worked with the Association of National Minorities in Germany , which was founded in 1924 .

In the following years numerous associations, cooperatives and a Sorbian Volksbank were established. The democratic conditions of the Weimar Republic now offered the Sorbs better opportunities to develop popular activities. Here, especially in Upper Lusatia , the numerous Sorbian associations did broad cultural and educational work.

National Socialism

After the NSDAP had first tried to integrate the Sorbs into the new structures and to collect them for their goals, as well as to integrate the Domowina into the Bund Deutscher Osten , the policy changed after it became clear that the Sorbian organizations were under Domowina chairman Pawoł Nedo resisted. From 1937 all Sorbian associations were banned and the use of Sorbian in public was severely restricted. Sorbian teachers and clergymen were transferred from Lausitz to distant parts of Germany. The regime tried to force the Sorbian people to assimilate . There were systematic arrests among the Sorbian intelligentsia; some of its most active representatives were imprisoned in concentration camps, some no longer lived to see the liberation (including Maria Grollmuß , Alois Andritzki ).

At the same time, the image of Lusatia in particular was changed for propaganda purposes, partly in an agrarian and romantic way ("Lusatia farmers"), then also with industrial-modern trains with reference to lignite ("upheaval").

Immediate post-war period

After the Second World War, the Domowina was one of the first organizations in the Soviet Zone whose activities were approved by the Soviet military administration before the defeated Germans were allowed to re-establish organizations. Because, according to Marshal Iwan Stepanowitsch Konjew , the "small people who live on the territory of Germany and had to endure so much under fascism deserved support." After its re-establishment on May 10, 1945 in Crostwitz , the Domowina resumed its work with the aim of preserving and revitalizing the Sorbian identity in Lusatia . Initially, she was only active in Upper Lusatia, because the resumption of work in Lower Lusatia at the instigation of the Brandenburg SED leadership under Friedrich Ebert and Cottbus District Administrator Franz Saisowa (SED) was not allowed until 1949 in view of their alleged separatist efforts. Sorbian activities were initially systematically suppressed, nationally conscious Sorbs were monitored and in some cases were temporarily detained (e.g. Mina Witkojc ). The Prague- based Lusatian-Sorbian National Committee ( Łužisko-serbski narodny wuběrk ) under the leadership of Pastors Jan Cyž and Jurij Cyž initially actually saw the future of the Sorbs in their ties to Czechoslovakia or in state independence and fundamentally refused to cooperate with German authorities from. The Domowina, on the other hand, soon decided to remain in a German state, especially since the Soviet Union had no interest in a Sorbian area separate from the Soviet Zone, and from March 1946 subordinated itself to the political line of the KPD; in autumn 1946 she agreed to the union of the SPD and KPD to form the SED and the establishment of uniform electoral lists.

The conflict between the two organizations, who consider themselves to be representatives of the Sorbian people, led in December 1946 to two Sorbian delegations traveling to the All-Slavic Congress in Belgrade . In the four years leading up to the founding of the GDR, the Sorbs were in close contact with other Slavic countries, not just with Poland and Czechoslovakia. On the Schadźowanka , a regular gathering of Sorbian students, in 1946 a representative of the Yugoslav military mission invited the Sorbian Youth Brigades ( Serbska młodźina ) to the Balkans. At that time, Yugoslavia was the only remaining state that openly supported the Sorbs' demands for political autonomy. The youth organization under the leadership of Jurij Brězan was still independent at that time and not part of the World League of Democratic Youth . No further visits were made after the break in relations between Moscow and Belgrade. The Sorbian Youth was incorporated into the FDJ in December 1948 .

The stream of refugees from expelled Germans from Silesia, the Sudetenland and other formerly German-populated areas put the Sorbian settlement area under great pressure. While Saxony was initially only a transit area for refugees, the Soviet administration declared it a settlement area in March 1946. According to statistics from Domowina, many formerly Sorbian villages were inhabited by more than 20 percent, some even more than 50 percent, by German-speaking refugees within a short time. As a result, especially in the Protestant part of the Sorbian area, the Sorbian church services were replaced by German ones in numerous places; Sorbian became a private language from everyday life. In the Catholic parishes, however, most of the newcomers were assimilated by the Sorbs.

In May 1947 the Soviet authorities allowed Domowina to set up a Sorbian printing house; in October she was finally recognized as the sole advocate of the Sorbs. Thus the Sorbian movement continued to move towards the line of the SED. At a meeting between the Domowina leadership under Pawoł Nedo and the SED chairmen Otto Grotewohl and Wilhelm Pieck , almost all of the Domowina's proposals, including the creation of an administrative unit in Lusatia and the recognition of the Sorbs as a people, were rejected. Lusatia remained divided and the Sorbs were only granted the status of a “part of the people”.

On March 23, 1948, the Saxon State Parliament passed the “Law to Safeguard the Rights of the Sorbian Population”, which for the first time laid down the Sorbs' right to promote their language and culture. In 1950 it was also introduced in the state of Brandenburg by ordinance , after the Domowina had only been allowed to resume its work there a year before, due to massive pressure from the Soviet administration and the Berlin SED leadership.

GDR time

In the early 1950s, the integration of the Sorbs into the socialist state apparatus continued. The previous Domowina chairman, Nedo, had not openly stood in the way of turning to Marxism-Leninism, but had repeatedly urged the national rights of the Sorbian people. He was replaced in December 1950 by Kurt Krjeńc , an old communist, who in the following years converted the Domowina into a satellite organization of the SED, whose core task was no longer the preservation and promotion of Sorbian culture, but the integration of the Sorbs into socialism. In the historiography, the role of the "Sorbian working people" was emphasized, that of other groups, e. B. those of the clergy and petty bourgeois important for the national movement, on the other hand, played down. Nevertheless, the Sorbian umbrella organization remained under close observation by the Ministry for State Security ; there was talk of “nationalist and Titoist machinations”. Personalities such as Pawoł Nowotny (head of the Institute for Sorbian Folk Research) and Pawoł Nedo, but also self-confessed communists such as Jurij Brězan, were under surveillance for possible “anti-state activities”. Until the 1970s, various Sorbian personalities were monitored for their protests against the expansion of the opencast mines and the construction of large power plants in Lusatia or against the establishment of LPGs in the Sorbian region, as well as later because of suspicious contacts with the Czechoslovak intelligentsia and imprisoned in individual cases.

The Sorbs also played a role in the process of recognition of the German Democratic Republic by Yugoslavia in the 1950s (as a result of which the Federal Republic of Germany broke off relations with Yugoslavia due to the FRG's claim to sole representation ). At that time, the GDR complied with Josip Broz Tito's request to employ a certain percentage of Sorbian employees in the embassy in Belgrade. Among other things, a Sorbe was appointed chief interpreter at the embassy. Shortly after the establishment of diplomatic relations on October 15, 1957, however, these were recalled.

The Sorbian people were officially recognized as a national minority in Article 40 of the GDR constitution of 1968 . In order to take Sorbian interests into account, departments for Sorbian matters (e.g. culture and domestic politics ) and state scientific institutions (new: Institute for Sorbian Folk Research; re-establishment: Institute for Sorbian Studies at the University of Leipzig ) have been set up in the respective GDR ministries. created. In order to ensure equality for the Sorbian population, various legal regulations were enacted. Sorbian school lessons and the bilingual labeling of public facilities and street signs were introduced in the German-Sorbian area.

Nevertheless, the official policy towards the Sorbs continued to be characterized by ideological tutelage and control, although a certain degree of independence could be maintained. In comparison with the national minorities of other countries, the Sorbian culture and science were able to develop here to an above-average breadth. Nevertheless, the decline of Sorbian as an everyday language happened faster than seldom before. In addition to the general tendency towards assimilation, there were also numerous political reasons for this: Both the initially ambitious educational program and the practical support for bilingualism by official bodies were gradually withdrawn from 1958 after Fred Oelßner's resignation . At the newly established A schools (schools with the Sorbian language of instruction), natural science subjects were again taught in German from 1962; the slogan “Lusatia is going bilingual” had already disappeared from the public eye with Fred Oelßner. In 1964, after pressure, especially from the energy workers who had moved in, Sorbian foreign language instruction in the B schools became optional. In 1962, 12,800 students learned Sorbian, at the end of 1964 it was only 3,200, and at the end of the 1960s even fewer than 3,000. The number of students in A schools, on the other hand, remained almost constant.

The collectivization of agriculture and the traditional family farms destroyed the only branch of the economy in which Sorbian was still the everyday language. The establishment of purely Sorbian LPGs was rejected; In practice, the majority of the Sorbian cooperatives were mostly run by Germans. The proposed establishment of Sorbian brigades in the Lusatian coal-fired power stations was also rejected. Existing problems between Germans and Sorbs could not be openly discussed, as criticism of the GDR nationality policy and addressing the differences between the state ideal and the latent hostility to sorbs rooted in a long tradition was not desired.

In addition, the Sorbian culture suffered sustained damage in the period after 1945 from the war-related mass immigration of German-speaking expellees and later skilled workers, the destruction of large areas by open-cast lignite mining , urbanization and finally the envisaged de-churching (the Sorbian identity was largely preserved through religious practice) which almost exclusively the Catholic Sorbs knew how to oppose.

These framework conditions, which the Domowina as a representative of the Sorbs could not oppose, but in the enforcement of which it also played an active role, led to a sharp decline in the Sorbian population between 1945 and 1990. While the GDR officially always spoke of 100,000 members of the people , the researcher Ernst Tschernik pointed out as early as 1955 that there are probably still 80,000 Sorbs, with a strong downward trend. His report was never allowed to be published. Shortly after reunification, however, the estimates were corrected to between 40,000 and 60,000. It can therefore be assumed that the number of Sorbs halved during the GDR era.

It was not until 1987 that the Domowina resumed contact with the Sorbian clergy of both denominations after its first secretary had to admit that around half of the members are Protestants and 20 percent are Catholics. The decade-long period during which many Sorbs - especially religious - had regarded the “red domowina” as a “traitor to Sorbian interests”, however, left its mark on their public perception and led to a massive decline in membership after reunification.

After reunification

With the end of the GDR, there were also new political frameworks for the Sorbs. In a declaration in March 1990, the Domowina spoke out in favor of German unity . In the same year the Wendish House opened in Cottbus . In 1991 the Domowina was reconstituted according to democratic principles. As a common state instrument of the federal and the two countries Brandenburg and Saxony was Foundation for the Sorbian People (založba za serbski invited) also established the 1991st

After the turn of the millennium, there were repeated protests by the Sorbian population, including against the closure of the Sorbian secondary school in Crostwitz (2001) or the plans of the federal government and the Brandenburg state government to promote Sorbian education, culture and science (2008). In 2009, an expert opinion by the Institute for Cultural Infrastructure, headed by Matthias Theodor Vogt, aroused the temptation, in which a radical restructuring of the Sorbian institutions, including the creation of a Sorbian parliament, was suggested.

Until recently, villages in the Sorbian settlement area were affected or threatened by forced resettlement as a result of lignite mining by LEAG , for example the villages of Rohne and Mulkwitz in the municipality of Runde , Sorbian places with their own dialect and customs. In the neighboring village of Mühlrose , the LEAG is sticking to the planned use since 2007 from around 2030 and the relocation of the place. After taking over the Welzow-Süd opencast mine , the LEAG initially did not comment on the future of Proschim , but the coalition agreement that has been in effect in Brandenburg since 2019 excludes the relocation of further sites for open-cast lignite mining.

From 2008 to 2017, Stanislaw Tillich was the first Catholic Sorbe to be head of government in Saxony.

Since 2014, various agencies have been pointing to an increasing number of right-wing extremist attacks on Sorbs.

Sorbian symbols

A Sorbian flag was first mentioned in 1842. After the Pan-Slavic Congress , which took place in Prague in 1848, it was given its current color scheme . The Sorbs flag was banned by the National Socialists in 1935, but officially used again by the Domowina since May 17, 1945. The Sorb flag was not mentioned in the flag laws of the German Democratic Republic, but its use for special occasions and holidays was regulated in ordinances of the councils of the districts of Cottbus and Dresden.

The Sorbian hymn is the song " Rjana Łužica " ("Schöne Lausitz") , which goes back to a poem by Handrij Zejler set to music by Korla Awgust Kocor in 1845 .

In the constitution of the Free State of Saxony and in the Sorbs / Wends Act (SWG) of the State of Brandenburg, it is now regulated that the Sorbian anthem and the Sorbian flag can be used alongside state symbols on an equal footing.

Rights of the Sorbs in Germany

In the unification treaty, the Federal Republic of Germany and the then GDR spoke out in favor of securing the continued existence of the Sorbs.

- Unification Treaty - Minutes (No. 14) on Article 35:

- "The Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic declare in connection with Article 35 of the Treaty:

- The commitment to the Sorbian people and culture is free.

- The preservation and further development of the Sorbian culture and traditions are guaranteed.

- Members of the Sorbian people and their organizations have the freedom to cultivate and preserve the Sorbian language in public life.

- The constitutional distribution of competences between the federal and state governments remains unaffected. "

The rights of the Sorbs are constitutionally anchored in the state constitutions of Brandenburg and Saxony, as well as in the Courts Constitution Act. The constitution of the state of Brandenburg in Article 25 (rights of the Sorbs / Wends) and the constitution of the Free State of Saxony in Article 5 (The People of the Free State of Saxony) and Article 6 (The Sorbian People) guarantee the right to preserve their national identity and language , Religion and culture. The Saxon constitution also defines the Saxon citizens of Sorbian ethnicity as an “equal part of the national people”.

The structure of the rights is regulated by the law on the structure of the rights of the Sorbs / Wends in the state of Brandenburg (SWG) of 7 July 1994 and the law on the rights of the Sorbs in the Free State of Saxony (Sächsisches Sorbengesetz - SächsSorbG) of 31 March 1999. Among other things, the bilingual labeling of traffic signs and bilingual signage in public spaces are regulated in the traditional settlement area (SWG § 11 and SächsSorbG § 10). Deviating from the principle of the German court language - § 184 sentence 1 Courts Constitution Act (GVG) - § 184 sentence 2 GVG allows the use of the Sorbian language in court within the home districts of the Sorbian population.

Bilingual house sign on the Brandenburg State Parliament building

Bilingual Sorbian-German signs in Crostwitz

Station sign in Hoyerswerda ( Upper Sorbian Wojerecy )

Sorbs in literature, film and television

literature

In his walks through the Mark Brandenburg (1862–1889), Theodor Fontane describes not only the history, but also the way of life, customs and costume of the Sorbs (Wends) in Lower Lusatia. In Wilhelm Bölsche's contemporary novel Die Mittagsgöttin (The Goddess of Midday) from 1891, the scenes are in the Spreewald in the then still mainly Lower Sorbian-speaking village of Lehde . Furthermore, the 2007 published novel called The Lady Midday by Julia Franck according to the known Sorbian legendary figure. The first part of the novel deals with the childhood of Martha and Helene in Bautzen , whose Sorbian housemaid suspects the cause of the mother's mental derangement in the curse of the midday woman.

Movie and TV

The animated film When there were Aquarians gave the DEFA based on a Sorbian fairy tales and deals among other Sorbian wedding customs. The crime film Der Tote im Spreewald was broadcast on ZDF in 2010 . One of the main characters is the son of a traditional Sorbian family who does not feel connected to his cultural roots. The film brought the Sorbian culture closer to a broad audience, but also reflected on the issues of homeland and minorities.

The Minet - minority magazine broadcast a program about the Sorbs with the title The Sorbs - a Slavic people in Germany on RAI 3 ( Sender Bozen ) in 2007 . Radiotelevisiun Svizra Rumantscha also made the film Ils Sorbs en la Germania da l'ost about the Sorbs in Germany in 2007 as part of the series Minoritads en l'Europa (Minorities in Europe) .

See also

- including Sorbian topics.

Web links

Generally

- Foundation for the Sorbian People - official website

- Project Rastko Lusatia , digital library about the Lusatian Sorbs of the Rastko project (Serbian / multilingual)

- Sorbian online map (Sorbian / German)

- The little language story: Sorbian on Deutschlandradio Kultur July 26, 2012

- The Wendish Museum Cottbus

- The Sorbs - a Slavic minority in Germany - Contribution by church historian Prof. Dr. Rudolf Grulich

Research and Teaching

- Sorbian Institute Bautzen

- Institute for Sorabic Studies at the University of Leipzig