Slavic mythology

The Slavic mythology describes the myths and religious beliefs of the Slavic peoples prior to their Christianization and its continuation in the form of " pagan " customs in Christian times. In general, the sources of pre-Christian Slavic mythology are very thin, most of the sources were written by Christian authors who were hostile to ancient pagan mythology. A polytheistic system with a multitude of deities , natural spirits and natural cults has been handed down , which corresponds to the original Indo-European religion and shows influences from neighboring cultures.

swell

Knowledge of the Slavic religious world comes from four main areas:

- Written documents that can be examined using historical methods , such as chronicles, documents or ecclesiastical tracts, have essentially come down to us from the late 10th to 12th centuries, even if the oldest report by Prokopius of Caesarea dates back to the 6th century originates. In the 10th century Arab travelers like Ahmad Ibn Fadlān described the Slavic area. Detailed descriptions of the gods and cults of the Elbe and Baltic Sea Slavs can be found in the chronicles of Thietmar von Merseburg , in Saxo Grammaticus and in the Chronica Slavorum by Helmold von Bosau . The pre-Christian religion of Bohemia was described by Cosmas of Prague , the Nestor Chronicle and the Igor Song bear witness to the cult of the Kievan Rus .

- The Archeology provides insights into places of worship and burial rites, but other areas of religious life are illuminated for example by finds of weapons, masks or jewelry.

- In the 19th and early 20th centuries, ethnography collected a rich fund of material on folk customs and beliefs, some of which could be traced back to pre-Christian tradition.

- The linguistics finally deals with the traditional names of gods and religious terms, allowing comparisons of local cults among themselves and with other language areas.

Relationships with other cultures

The most obvious reference to the connection between Slavic and Indo-European mythology is the cult of the god of thunder , which the Slavs called Perun . Numerous other parallels also exist to the mythology of the Iranians , Balts , Germanic peoples , Celts and the ancient cultures of the Greeks and Romans . Examples include Oracle cults , the cremation or the many heads of the gods . The comparative linguistics has worked out a shared roots of the names of gods and other religious denominations. However, it is not always clear whether the similarities come from the common Indo-European basis or from later cultural contacts.

Cosmogony and cosmology

Slavic cosmogony is similar to that of other Indo-European mythologies. The absolute ground state is a nothing that is represented by Rod (-Rodzanice) . With the beginning of the flow of time, Rod becomes a cosmic egg from which the white god , Bieleboh , and the black god , Czorneboh , develop. Rod is nondualistic , the feminine aspect is represented by Rodzanice . The dualistic deities Bieleboh and Czorneboh arise only when they hatch from the cosmic egg . In different regions of Slavic mythology, the Bieleboh and the Czorneboh are represented by different deities.

There are several variants of mythology below. In one the world arises from the body of Rod, similar to how the world arises from the giant Ymir in Nordic mythology , in a second the White God and the Black God create the world:

This good and evil power lift the earth up out of the sea and make it grow, the good power being responsible for the fertile tracts of land, the evil for the wastelands and swamps. In the course of Christianization, the two powers, Bieleboh and Czorneboh , were reinterpreted as God and the Devil . They were depicted as two birds pecking and carrying sand from the ocean floor. Good and evil are equally involved in the creation of man : the soul is of divine origin , the devil creates the body and thus the basis for all weaknesses and diseases up to death.

The idea of the world is personified. The sky , the earth and the heavenly bodies will be presented as supernatural beings. The goddess Mokosch is assigned to the earth, the god Svarog to the sky . Among the celestial bodies, in addition to the sun and moon, Venus especially enjoyed cultic veneration.

Gods

Main gods

The fact that the local gods have a common origin is proven by the word bog for god, which can be found in all Slavic languages. Four main gods are known from the original Slavic pantheon :

- Svarog , creator of all life, god of light and heavenly fire, sky smith

- Svarožić , also Dažbog, the son of Svarog, sun god, mediator of divine life on earth, giver of good

- Perun , god of thunderstorms, thunder and lightning, god of war and supreme god of the Slavs, as well

- Veles , originally protector of the dead, god of cattle, fertility, wealth, and later also god of justice

Svarog appears as God-Father, who remains inactive after the creation of the world and hands over power to the younger generation of gods. The highest active god and ruler of the world is Perun, who is even mentioned by Prokopius as the only god of the Slavs. Next to him are the sun god Svarožić and the fertility god Veles. This division corresponds to the functional three-part division of Indo-European deities according to the theory of Georges Dumézil .

Gods of the Eastern Slavs

In addition to the main gods, regional and local deities were worshiped in all Slavic areas. For the Kievan Rus , the Nestor Chronicle reports that Prince Vladimir I set up six idols in 980. In addition to Perun and Dažbog, there are:

- Stribog , presumably a wind god

- Choir , probably a moon deity

- Simargl , a god in animal form whose jurisdiction remains unclear, and

- Mokosch as the only goddess in the Kiev pantheon, the earth mother and personification of the “damp mother earth ”, goddess of fertility and femininity, protector of sheep and of spinning and weaving

It remains unclear whether the Trojan, mentioned several times in Russian sources, should be regarded as a god, a mythical hero or a demon. He is often associated with the Roman emperor Trajan , who was also deified by the Sarmatians and Alans . In Serbian sagas, Tsar Trojan appears as a three-headed demon who devours humans, cattle and fish.

Gods of the Elbe and Baltic Sea Slavs

In contrast to the other Slavic tribes, the Elbe and Baltic Sea Slavs, under pressure from Christian missionaries, developed an organized temple cult with their own caste of priests. The original gods of nature became tribal gods, and they were often given new functions. Oracle rites took place in their temples, giving information about the outcome of wars or future harvests. The main gods of the three most powerful tribes were:

- Svarožić or Radegast. The original sun god became the tribal and war god of the Redarians , later he got a leading role in the entire tribal association of the Liutizen and also among the Obodrites .

- Svantovit , the god of the rans . His cult spread from Rügen to the mainland in the 12th century , and his temple in Jaromarsburg became the main religious center of all the tribes that were not yet subjugated.

- Triglaw , a god of the Pomorans , was originally only worshiped in Wollin , Vineta and Stettin , later also in Brandenburg .

In addition, minor gods are known from some regions. The Ranen revered rugiewit , Porevit and Porenutius in Wolgast and Havelberg , the cult of is Jarovit occupied, the Wagrians honored Prove and Podaga that polabians Siva . In the area of the Lusatian Sorbs there are two mountains called Bieleboh and Czorneboh. Czorneboh (the black god) is mentioned by Helmold von Bosau, Bieleboh (the white god) is his hypothetical opponent. However, these geographical names come from later times.

Nature spirits and demons

The Dämonolatrie , so the cult of nature spirits and demons , occupied a large space in the pre- and non-Christian Slavic religion. While the cults of gods disappeared soon after Christianization, the belief in the lower beings, who embody the forces of nature, persisted into modern times. Many of the original nature spirits became ghosts in popular belief .

Elementals

The worship of the four elements earth, water, air and fire can be found throughout the Slavic area. The personification is significant: it was mostly not the elements themselves, but the beings living in them that were worshiped.

Beings that inhabited rocks, grottos, stones and mountains were considered to be earth spirits. “Holy” mountains were for example Sobótka in Silesia, Říp and Milešovka in Bohemia, Radhošť in Moravia and Bieleboh and Czorneboh in Lusatia. Mountain spirits appeared as groups in the form of nymphs - Kosmas calls them oreads - or as individuals. Often it was giants like Rübezahl or the Russian Swjatogor , or dwarfs like the Permoniki , who were revered and feared by the miners. A material testimony to the stone cults are the bowl stones, which were used for ritual acts in Belarus until the beginning of the 20th century.

Water spirits were found in lakes, wells, springs and rivers. Thietmar von Merseburg from the area of the Daleminzier and Redarians mentions magical lakes that functioned as oracles , sacrifices for springs and wells are attested from Bohemia in the 11th century and from Russia in the 13th century. The water spirits, known as Vilen or Rusalken , were, like the mountain nymphs, female group beings , while the male Aquarius was a loner.

The air spirits include the wind demons and their brother Djed Moros , who brings wintry weather. The mother or wife of the wind, Meluzína , warned of calamities and natural disasters. A very evil air creature known throughout the Slavic region was the Baba Yaga , who flew through the air on a roller of fire and ate human flesh.

In the fire cult, special attention was paid to the hearth fire , ritual fires were part of the festival of the summer and winter solstice . Among the fire demons are dragons and smaller flying creatures that could often be hatched from an egg. In connection with the ancestor cult are the will- o'- the- wisps , souls of the deceased who lead living people astray.

Vegetation deities, zeitgeist and fate deities

Vegetation demons guarded the grain in the fields and the game in the forests. They misled hikers or, like Hejkal , caused noise in the forest. Often "holy" trees are attested that were not allowed to be felled because they were inhabited by a spiritual being. Zeitgeist, who protected certain periods of time, are closely related to the vegetation deities. The midday woman was known to all Slavs, and similar spirits were also assigned to evening and midnight.

The female goddesses of fate, who usually appear in threes and determine the lot of a newborn, are known in every Indo-European culture, for example as Norns among the Teutons. The personification of illness and death also appeared in many variations.

House ghosts

The cult of the house ghosts has been documented since the 11th century and continues to this day. House spirits as protectors of every house were sometimes the souls of the ancestors, sometimes dwarfs or animal forms, especially snakes . The ban on killing a snake in the house so that no misfortune would come upon the residents was widespread. Archeologically documented are food, animal and human sacrifices in foundations, which should also ensure the protection of newly built houses.

Cult of the dead and ideas of the afterlife

At the moment of death, according to the Slavs, the soul left the body and escaped from the house through a window that had to be open because of this, or through a hole in the wall. It then either remained permanently in place, or after a while it went into the hereafter. Both the ferryman who took the dead into the underworld for a fee and the bridge that had to be crossed were known.

The dead body was cremated. Many sources testify that the Slavs practiced widow burning . From the 8th to 9th centuries, under the influence of Christianity, body burial prevailed. This was a prerequisite for the later widespread belief in vampires , night albums , werewolves and other human demons; however, living people were also suspected of transforming themselves in their sleep.

Cult objects and rituals

Place of worship were holy generally groves , simple sacrificial sites in the open air or sacrificial stones . Temples only existed in the Elbe and Baltic Sea Slavic regions and in the late Kievan Rus . Temples of national importance were Rethra , the main sanctuary of the Liutizen , which has not yet been proven archaeologically, and the sanctuary of Svantovit in the Jaromarsburg on Rügen. In the port cities of the Pomorans , especially in Wollin and Stettin , there were several temples dedicated to different gods. A sanctuary that has not been documented in written sources was discovered in Groß Raden in Mecklenburg . However, the archaeological findings support the descriptions of the temples elsewhere.

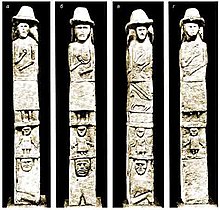

The gods and spirits have been depicted since the early days. The idols were made of wood or stone; according to written sources, the main gods also received idols made of gold and silver. Although statues up to 3 meters high have been found, the most common finds are small figures. The tribal gods were assigned insignia , which underlined their power and were often carried with them in war: flags, lances, swords and other magical weapons. A characteristic of Slavic idols is the many-headedness. Many gods were depicted with two, three, four or seven heads.

With the exception of the Elbe and Baltic Sea Slavs, who were under pressure from their Christian neighbors, the cults were hardly organized. A separate priesthood has evidently only developed there, especially among the tribes of the Liutizen , Obodriten and Ranen , who did not convert to Christianity until their political submission. In contrast, sorcerers , witches and fortune tellers are known in all Slavic regions who practiced cults and magical rituals as individuals.

Sacrifices , oracles and ritual feasts are documented as elements of god worship . The most important public rites were linked to agricultural magic , such as the feast of the summer and winter solstices or the beginning of spring . Some of them have survived into modern times in the form of folk customs such as the burning of the Morena or the Iwan Kupala Day .

Dynastic myths and heroic sagas

Mythical accounts of the origin of the tribe and the ruling dynasty have survived from Poland , Bohemia and the Kievan Rus . The Czech legends tell about the forefather Čech and his successors, the legendary ancestors of the Přemyslid dynasty . The Russian legends in turn know the forefather Rus . The Polish prince Krak , founder of the city of Krakow and dragon slayer , and the equally legendary Duke Lech were considered to be the founders of the orderly state in Poland. The emergence of Kiev is attributed to the three brothers Kyj, Shchek and Choriw , whose eldest, Kyj, also acted as a dragon fighter. In the Sorbian song Wójnski kěrluš , which presumably dates back to the 10th century, there is an account of a tribal leader at the time of the Hungarian invasions.

The Russian bylins and the South Slavic heroic songs are more recent . The bylins depict the battles against the Tatars . The legendary Russian heroes, the Bogatyri , whose most famous Ilya Muromets are, fight against human enemies, dragons and other evil forces. The greatest hero of the Bulgarian, Serbian and Macedonian heroic songs is Prince Marko , participant in the Battle of the Blackbird Field in 1389. The East and South Slavic heroic songs mostly refer to historical events, but deal with numerous older mythological motifs.

literature

- Jakub Bobrowski et al. Mateusz Wrona: Mitologia Słowiańska , Bosz, Olszanica 2019, ISBN 978-83-7576-325-6 (Polish)

- Patrice Lajoye (Ed.): New researches on the religion and mythology of the Pagan Slavs , Lingva, Lisieux 2019, ISBN 979-10-94441-46-6

- Michael Handwerg: The Slavic Gods in Pomerania and Rügen , Edition Pommern, Elmenhorst 2010, ISBN 978-3-939680-06-2

- Aleksander Gieysztor: Mitologia Słowian , 3rd edition, WUW, Warsaw 2006, ISBN 978-83-235-0234-0 (Polish)

- Mike Dixon-Kennedy: Encyclopedia of Russian and Slavic Myth and Legend , ABC Clio, Santa Barbara 1998, ISBN 978-1-57607063-5 (English)

- Nikolai Mikhailov: Baltic and Slavic Mythology , Actas, Madrid 1998, ISBN 978-8-48786363-9 (German and Spanish)

- Zdeněk Váňa: The world of the ancient Slavs , Dausien, Hanau 1996, ISBN 978-3-768443-90-6

- Leszek Moszyński: The pre-Christian religion of the Slavs in the light of Slavic linguistics , Böhlau, Cologne 1992, ISBN 3-412-08591-X

- Zdeněk Váňa: Mythology and gods of the Slavic peoples. The spiritual impulses of Eastern Europe , Urachhaus, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-87838-937-X

- Joachim Herrmann: World of the Slavs. History, society, culture , Urania, Krummwisch 1986, ISBN 978-3-332000-05-4

- Karl H. Meyer: The Slavic Religion , in: Franz Babinger u. a .: The religions of the earth. Their essence and their history , Münchner Verlag, Munich 1949, without ISBN

- Aleksander Brückner : Die Slaven ( Religionsgeschichtliches Reader ), 2nd edition, Mohr, Tübingen 1926, without ISBN

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Victor A. Shnirelman: Obsessed with Culture: The Cultural Impetus of Russian Neo-Pagans. In: Kathryn Rountree: Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Pp. 87-108. ISBN 978-1-137-57040-6

- ↑ Dmitriy Kushnir: Songs of Bird Gamayun: The Slavic Creation Myth (The Slavic Way Book 3), CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; Edition: 1 (December 7, 2014), ISBN 978-1-5054-2424-9 , p. 5