Fortune telling

As fortune telling or divination , pejorative fortune telling , numerous practices and methods are summarized, which are intended to predict future events and to determine present or past events that are beyond the knowledge of the questioner. The description of fortune telling falls into the subject areas of cultural history , religious studies or ethnology . The names are in the literature mantic (from ancient Greek μαντικὴ τέχνη mantikḗ téchnē , art of interpretation of the future ') and divination (of Latin divinatio , divination', actually, exploration of the divine will ') use. Divination is not only understood to mean the revelation of the future, but any interpretation of the signs of the gods.

Whether fortune tellers can actually predict future events has not been the subject of scientific discussion since the 18th century. Churches and theologians attribute belief in this to superstition . The Catholic Church and leading Protestant theologians therefore resolutely reject fortune-telling and argue that it is a matter of man's presumption of God and that it is incompatible with Christian faith.

Definition and classification

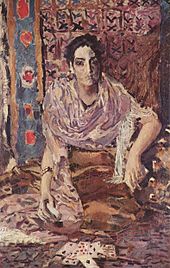

In contrast to forecasters who refer to normal causal relationships that are fundamentally understandable for everyone, fortune tellers claim to have knowledge of occult relationships that is hidden from the ignorant and that enables them to look into the future. Some fortune tellers claim to have immediate, intuitive access to knowledge about the future, also known as “second sight” or precognition , others interpret signs that they regard as symbols for the future. There are two types of sign interpretation: Either the fortune teller interprets events or facts that he has not influenced as signs from which the future can be read, or he himself causes an event according to certain rules, the course or result of which he then transfers as encrypted information Understanding and interpreting the future. The first type includes, for example, the interpretation of celestial constellations ( astrology ) and unusual weather phenomena or palm reading ( chiromancy ), the second type card reading or throwing foracles, in which from the throw of an object (dice, bones, eggs in the egg oracle and others) the Answer to a posed future-related question is read. The distinction between "natural" (immediate) and "artificial" (based on the interpretation of signs by experts) acquisition of future knowledge was already made in the ancient divination theory. A somewhat different classification, particularly based on the shamanic practices of ethnic religions , distinguishes between intuitive divination, in which the fortune teller relies exclusively on knowledge intuitively taken from his own mind, "possession prophecy", in which gods or other disembodied beings temporarily possess a body should take to convey messages about him, and "wisdom prophecy", in which the fortune-teller claims that the basis of his future knowledge are known objective laws, from which he draws appropriate conclusions in individual cases.

Religious prophecy or prophecy is differentiated from fortune telling . These are forward-looking assertions that claim immediate divine inspiration . The prophet or prophet appears as the commissioned herald of a divine plan. Prophecy usually relates to the fate of peoples or of all humanity, divination to the fate of individuals or smaller groups. The distinction between prophecy and fortune telling is not always clearly possible and imprecise language use is common. Originally and well into the 16th century, a “fortune teller” or “fortune teller” ( Old High German wīz (z) ago , Old Saxon wārsago , Middle High German wārsage ) was understood to be a prophet. Only in modern times did the word “fortune teller” acquire its current meaning.

Philosophical basis

The various forms of divination are based on a worldview that is based on a uniform structure of the entire cosmos, which is always and everywhere based on the same qualitative principles. The world is considered to be constructed in such a way that its parts are structured analogously and mirror one another. It is assumed that there are hidden but recognizable legal relationships or analogies between spatially and temporally separated areas. Phenomena of different kinds, between which no causal connection can be shown, are traced back to a uniform organizational principle of the world order and thus linked with one another. A strict parallelism between the cosmic or heavenly and earthly or human is assumed. In the context of this worldview, it is assumed that there are also detailed analogy relationships between the perceptible and the (still) hidden. The knowledge of the nature of these relationships should make it possible to grasp the hidden - including the future. This assumption forms the basis for the soothsayer's claim to be able to make accurate predictions; because he claims to know the relevant laws. In some cases it is assumed that the future knowledge is only directly accessible to a divine authority, but is revealed by the deity to a person through visions or dreams.

Most of the time the future is not considered to be immutable. Rather, divination is intended to serve the purpose of recognizing impending disaster at an early stage and taking appropriate measures to avert it. Nevertheless, the ideological premises on which divination starts lead to philosophical problems that are related to the question of determinism (predetermination, inevitability) and free will . A claim to truth made for statements about the future presupposes that it is already certain in the present that something will inevitably occur. Accordingly, not only what is predicted by the fortune teller is determined, but also the fact that the fortune teller is consulted. This assumption leads to a fatalistic or deterministic philosophy and threatens the notion of free will. The problem can be avoided if it is assumed that what is predicted is not immutable, but that someone warned by divination can still influence his future fate. With this, however, the truth claim of fortune-telling is relativized and restricted to a greater or lesser extent and a verification of its correctness becomes impossible.

Psychological aspects

The social and religious historian Georges Minois has presented a comprehensive account of the history of divination. According to him, 25 different prediction methods are common, "from the crystal ball to the coffee grounds , from geomancy to numerology , from chiromancy to cartomancy ". Minois explains the continuing wide spread of the practices socio-psychologically . He sees the main reason for the continuing popularity of fortune telling in the modern age not in the need to gain knowledge about the future, but in the social function of the relationship between the fortune teller and his customer seeking orientation. The customer seeks comforting human contact in troubled and unstable times. A prediction is never neutral, it is about addressing the intentions, wishes and fears of the customer and an impetus for taking measures. The prediction always implies an instruction to act, it is inextricably linked with the steps to which it leads. A prediction that "helps, relieves, calms and stimulates action" is supposed to function as a therapy.

The religious historian Walter Burkert has a similar opinion . He thinks that the “gain in courage that the 'signs' bring in as decision-making aid” is “so considerable that occasional falsification through experience does not arise”, and comes to the conclusion that “decision-making aid, the strengthening of self-confidence, is more important as actual foreknowledge ".

history

In the advanced cultures of the ancient Orient , divination was practiced especially on behalf of the rulers. Numerous sources from Mesopotamia provide a wealth of details. The most important procedure was that already in the middle of the 3rd millennium BC. Inscribed inspection of the viscera . In most cases, conclusions were drawn about the will of the gods and the expected outcome of a project from the condition of the liver of a slaughtered sacrificial animal . The cognitive value of the fortune telling methods used was assessed differently, but the principle as such was not challenged.

In ancient Greece, especially the bird's eye view (interpretation of the flight of birds), the liver view, the dream interpretation and the oracle being were widespread. At the famous oracle sites, oracles were proclaimed as answers to questions asked by the gods. Often the oracles did not contain any clear statements about the future, but rather mysteriously formulated information or instructions that could be interpreted in different ways.

In the Roman Empire bird viewing (augurium) and entrails were also among the most important methods, they were practiced by the state. The aim was not to look directly into the future, but to answer the question of whether the gods were in agreement with a political or military project and whether this could therefore be considered promising. In addition to this state divination, which was carried out by priests' colleges, there was the private one to investigate the future fate of individual individuals. The Roman authorities suspected the divination carried out by professional fortune tellers outside of state institutions. Many people announced fortune tellers that they would gain imperial dignity, which the ruling ruler viewed as subversion. The undesirable consequences of politically relevant divination - including predictions about the death of the emperor - led to divination being regulated and restricted or prohibited by law.

In ancient times, violent and widespread criticism arose against divination. Homer already speaks of fundamental rejection . However, in Homer there are often oracles that come true, for example in the Odyssey (9.504), where the Cyclops Polyphemus admits that a seer once prophesied to him that Odysseus would blind him. In philosophical circles, the idea of a predictable future was problematized for fundamental considerations and sometimes radically rejected. Opponents of fortune telling were in particular the Cynics , the Skeptics and the Epicureans, as well as many Peripatetics and Cicero . Apart from fundamental philosophical objections, the criticism ignited the unreliability of the predictions and above all the commercial interests of the professional fortune-tellers, who were attacked as charlatans. The conscious production of alleged signs for the purpose of manipulation was also discussed. Writers such as the satirist Lukian von Samosata took up the skepticism and processed the criticism of fraud and gullibility in literary terms. In Greek comedy , fortune tellers were ridiculed as greedy fraudsters and their political influence was denounced as warmongering and disastrous.

The Christian church viewed biblical prophecy as an authentic, divinely legitimized transmission of knowledge about the future. The claim of fortune tellers to be able to predict the future, however, met with radical rejection from the ancient church fathers . They saw in it a presumption, a human encroachment on a sphere reserved for God. In addition, divination was related to the ancient Greek and Roman religions , which Christians hated, and was considered the work of the devil. In the course of the Christianization of the Roman Empire in the 4th century, there were strict legal prohibitions of divination. Also late antique councils imposed bans. However, state intervention against divination in late antiquity was not an exclusively religious concern of Christian rulers, but the measures also continued a restrictive policy that had already been initiated by the anti-Christian emperor Diocletian . The frequent repetition of the prohibitions shows that they only partially achieved the desired effect and that the topic remained topical.

Divination was widespread in the Middle Ages and early modern times . Church authorities and some theological authorities continued to oppose it and suppress it, but it also found defenders among medieval philosophers and theologians. In the later Middle Ages soothsayers gained considerable influence not only in royal courts, but also in the church. Some rulers, including Emperor Friedrich II , employed court astrologers. From the 14th century onwards, astrologers were even active in the papal curia ; during the Renaissance , popes and cardinals took astrological advice.

In addition, there have been Christian forms of prediction since antiquity, which were accepted in church circles and were particularly popular in hagiography . Saints have often been credited with the ability, thanks to divine inspiration, to foresee the future (such as death). The rich mediaeval vision literature reported on divine revelations, which often also contained predictions. A partly philosophical, partly physically or historically argumentative criticism of the future predictions increased from the end of the 16th century and supplemented the traditional religiously motivated criticism, but also evoked a wealth of counter-writings.

Opposing positions

One of the declared opponents of divination is the Catholic Church, which states in its catechism, among other things:

"All forms of fortune-telling are to be rejected: the servitude of Satan and demons , necromancy or other acts that are wrongly believed to 'unveil' the future. Behind horoscopes , astrology, palmistry, interpreting omens and oracles, clairvoyance and questioning a medium hides the will to power over time, history and ultimately over people, as well as the desire to incline the secret powers. This contradicts the loving awe filled respect that we alone owe God. "

The attitude of Protestant churches is more conciliatory. The Evangelical Information Center sees the use of divination as the satisfaction of a basic human need with which every religion has to deal. Fortune telling, however, could not be a way for the Protestant regional churches, because these churches "want to be consciously in agreement with the rational-scientific understanding of the world". Instead, it is recommended to "face the uncertainty of the future, knowing that God will not leave believers alone, whatever the coming".

Other reception

The Society for the Scientific Investigation of Parasciences (GWUP) publishes an annual “prognosis check”, which is based on a blog by private person Michael Kunkel and in which a series of publicly made predictions by astrologers, fortune tellers and clairvoyants are commented on. Regarding the fact that fortune tellers enjoy great popularity and that clients often report amazing "hits", while in "controlled experiments no hit rates exceeding chance could be determined", the GWUP points to the explanatory patterns of cold reading , the Barnum- Effect and Self-Fulfilling Prophecy .

According to the ancient orientalist Stefan Maul , the fundamental inclusion of fortune telling and oracles in economic, military and political decisions was an important factor for the success of Mesopotamia, which lasted over two millennia . What was decisive, however, was which question was asked how and at what point in time.

literature

Sources and representations from the perspective of fortune tellers

- Gabriele Hoffmann : fortune telling. Signpost for fate and future . Hugendubel, Kreuzlingen 2007, ISBN 3-7205-6022-8 .

- Albert S. Lyons: The Great Book of Fortune Telling . Dumont, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-8321-7389-7 .

- Eva-Christiane Wetterer: The hot line to the future. Heyne, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-453-67011-6 .

Investigations

- 1968, Joachim Telle : Finds on empirical-mantic prognosis in the medical prose of the late Middle Ages. In: Sudhoffs Archiv 52, pp. 130-141.

- 1970, Joachim Telle: Contributions to the mantic specialist literature of the Middle Ages. In: Studia neophilologica 47, pp. 180-206.

- 1987, Francis B. Brévart: Mondwahrsagetexte (German). In: Author's Lexicon . 2nd Edition. Volume 7, Col. 674-681.

- 1998, Georges Minois: History of the Future. Oracle, prophecies, utopias, forecasts . Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf and Zurich. ISBN 3-538-07072-5 .

- 2001, Matthew Hughes, Robert Behanna, Margaret L. Signorella: Perceived accuracy of fortune telling and belief in the paranormal. In: The Journal of social psychology 141, pp. 159-160. PMID 11294162 ISSN 0022-4545 .

- 2005, Wolfram Hogrebe (Ed.): Mantik. Profiles of prognostic knowledge in science and culture . Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg. ISBN 3-8260-3262-4 .

- 2007, Kocku von Stuckrad : History of Astrology. From the beginning to the present (= Beck'sche Reihe Volume 1752), Beck, Munich. ISBN 3-406-54777-X .

- 2013, Stefan Maul : The art of fortune telling in the ancient Orient . Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-64514-3 .

Web links

Remarks

- ^ Fritz Graf : Divination / Mantik . In: Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart , 4th edition, Volume 2, Tübingen 1999, Sp. 883–886, here: 883–885.

- ↑ Evan M. Zuesse: Divination: An Overview . In: Lindsay Jones (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Religion , 2nd Edition, Vol. 4, Detroit et al. 2005, pp. 2369-2375, here: 2370-2372.

- ↑ See the examples in Will-Erich Peuckert : Prophecy and Prophecies . In: Concise Dictionary of German Superstition , Volume 9, Berlin 1938/1941, Sp. 358–441. Cf. Wassilios Klein: Prophets, Prophecy. I. Religious history . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Vol. 27, Berlin 1997, pp. 473–476, here: 473f.

- ^ Friedrich Kluge : Etymological Dictionary of the German Language , 21st edition, Berlin 1975, pp. 832, 850; Wolfgang Pfeifer: Etymological Dictionary of German , Volume M – Z, 2nd edition, Berlin 1993, p. 1552.

- ↑ For analogy thinking see Veit Rosenberger : Tame Gods. The productive system of the Roman Republic. Stuttgart 1998, pp. 94-97.

- ↑ For the ideological basics see Stefan Maul : Divination. I. Mesopotamia . In: Der neue Pauly , Volume 3. Stuttgart 1997, Sp. 703-706; Francesca Rochberg: The Heavenly Writing. Cambridge 2004, pp. 1-13; Michael A. Flower: The Seer in Ancient Greece. Berkeley 2008, pp. 104-114.

- ↑ For an ancient discussion of this problem, see François Guillaumont: Le De divinatione de Cicéron et les théories antiques de la divination. Bruxelles 2006, pp. 214-253.

- ↑ Georges Minois: History of the Future , Düsseldorf 1998, p. 712.

- ↑ Georges Minois: History of the Future , Düsseldorf 1998, pp. 19f., 716.

- ↑ Walter Burkert: Greek Religion of the Archaic and Classical Epoch , Stuttgart 1977, p. 181.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Greek religion of the archaic and classical epoch , Stuttgart 1977, p. 184.

- ^ Stefan Maul: Divination. I. Mesopotamia . In: Der neue Pauly , Volume 3, Stuttgart 1997, Sp. 703-706. For details of divination among the different peoples see Manfried Dietrich , Oswald Loretz : Mantik in Ugarit , Münster 1990; Giovanni Pettinato: The oil prophecy among the Babylonians , 2 volumes, Rome 1966; Annelies Kammenhuber : Oracle practice, dreams and show of signs among the Hittites , Heidelberg 1976; Frederick H. Cryer: Divination in Ancient Israel and its Near Eastern Environment , Sheffield 1994; Ann Jeffers: Magic and divination in ancient Palestine and Syria , Leiden 1996; Willem H. Ph. Römer: Interpretations of the future in Sumerian texts . In: Otto Kaiser (Ed.): Texts from the environment of the Old Testament , vol. 2: oracles, rituals, building and votive inscriptions, songs and prayers , Gütersloh 1986–1991, pp. 17–55; Rosel Pientka-Hinz: Akkadian texts of the 2nd and 1st millennium BC 1. Omina and prophecies . In: Texts from the environment of the Old Testament , New Series Volume 4: Omina, oracle, rituals and conjurations , Gütersloh 2008, pp. 16–60.

- ↑ For details, see David E. Aune: Prophecy in Early Christianity and the Ancient Mediterranean World , Grand Rapids 1983, pp. 23–79; Sarah Iles Johnston: Ancient Greek Divination , Malden 2008, pp. 125-143; on the public use of oracles Christian Oesterheld: Divine Messages for Doubting People , Göttingen 2008 (especially pp. 534–569 about oracles as regulators of social action).

- ↑ On state divination see Veit Rosenberger: Tame Gods. The Prodigienwesen of the Roman Republic , Stuttgart 1998, pp. 46–71.

- ↑ Jörg Hille: The criminal liability of the mantic from antiquity to the early Middle Ages , Frankfurt 1979, pp. 51-64.

- ↑ Michael A. Flower: The Seer in Ancient Greece , Berkeley 2008, pp. 133-135.

- ↑ Jürgen Hammerstaedt : The oracle criticism of the cynic Oenomaus , Frankfurt 1988 (edition with introduction and commentary).

- ↑ On philosophical criticism see Friedrich Pfeffer: Studies on Mantik in der Philosophie der Antike , Meisenheim 1976, pp. 104–112; specifically on Cicero François Guillaumont: Le De divinatione de Cicéron et les théories antiques de la divination , Bruxelles 2006, pp. 214–354.

- ↑ For a case study, see Michael A. Flower: The Seer in Ancient Greece , Berkeley 2008, pp. 114–119; see. Pp. 132, 138f.

- ↑ Michael A. Flower: The Seer in Ancient Greece , Berkeley 2008, pp. 135f.

- ↑ Michael A. Flower: The Seer in Ancient Greece , Berkeley 2008, pp. 175f.

- ↑ Nicholas D. Smith: Diviners and divination in Aristophanic comedy . In: Classical Antiquity 8, 1989, pp. 140-158.

- ↑ For details see the detailed account by Marie Theres Fögen : The expropriation of fortune tellers. Studies on the imperial monopoly of knowledge in late antiquity , Frankfurt am Main 1993, p. 11ff.

- ↑ On the attitude of the ancient Christians see Pierre Courcelle: Divinatio . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Volume 3, Stuttgart 1957, Sp. 1235–1251, here: 1241–1250; Jörg Hille: The criminal liability of the mantic from antiquity to the early Middle Ages , Frankfurt 1979, pp. 64–81.

- ↑ On the early medieval conditions see Jörg Hille: Die Strafbarkeit der Mantik von der Antike bis zum Früh Mittelalter , Frankfurt 1979, pp. 81–116.

- ↑ Gerd Mentgen: Astrology and Public in the Middle Ages , Stuttgart 2005, pp. 161–273.

- ↑ For medieval and early modern fortune telling see Margarethe Ruff: Zauberpraktiken als Lebenshilfe , Frankfurt 2003, pp. 29-62 and the articles in the collection of essays by Klaus Bergdolt and Walther Ludwig (eds.): Zukunftsvoraussagen in der Renaissance , Wiesbaden 2005.

- ↑ III: "You shall have no other gods besides me"

- ↑ Georg Otto Schmid 1995 at relinfo.ch

- ↑ GWUP forecast check for 2011

- ↑ Inge Hüsgen, Wolfgang Hund: Fortune Teller ( Memento of the original from June 11, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Deutschlandfunk.de , April 5, 2015, Interview, with Stefan Maul : "A slap in the face for the modern, enlightened person"