shaman

The term shaman originally comes from the Tungusian peoples , šaman means “someone who knows” in the Manchu-Tungus language and denotes a special bearer of knowledge. In the Siberian and Mongolian Evenki word has Saman a similar meaning. In German , the term shaman, borrowed from travelers from Siberia , became widespread since the end of the 17th century and is used in two different readings, which can be deduced from the respective context:

- In the narrower, original sense, shamans are exclusively the spiritual specialists of the ethnic groups of the cultural area of Siberia (Nenets, Yakuts, Altaians, Buryats, Evenks, also European Sami, etc.), for whom the presence of shamans was considered to be the most important common characteristic by European researchers of the expansion period .

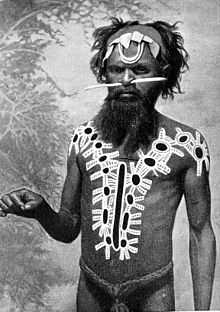

- In the broader, frequently used sense, the term shaman serves as a collective term for very different spiritual, religious, healing or ritual specialists who act as mediators for the world of spirits among various ethnic groups and who are assigned corresponding magical abilities. In most parts of the world they use this in the sense of cultic and / or medical acts for the good of the community. To do this, they practice various mental practices and rituals (partly with drug use), with which normal sensory perception is to be expanded in order to be able to establish contact with the “powers of the transcendent hereafter ” for various reasons . In this context, the medicine man (in the original and narrower sense the “companion and advisor of North American Indians for dealing with their medicine, the power from contact with spiritual and natural beings”, in the broader sense a healer from traditional cultures ) or the medicine woman American or Australian tribes called shamans . In addition, so-called necromancers from Africa or Melanesia (various magicians, healers, fortune tellers, etc.) - who, in contrast to the "all-round specialists" of the other continents, only cover a few tasks - are sometimes called shamans .

The very generalizing and undifferentiated use of this term for the religious-spiritual specialists of non- Siberian ethnic groups (as is customary in the context of the so-called shamanism concepts) is criticized by some scholars and indigenous peoples because it suggests the equality of very different cultural phenomena. They advocate using the respective regional names instead.

Different necromancers regardless of gender are or were actors of many ethnic religions , but can also be found in some popular religious manifestations of the world religions, such as Buddhist and Islamic cultures. In the case of some traditional indigenous communities in particular , they still play a role today - albeit often significantly weakened and changed. The existence of ritual experts presumably goes back at least to the magical-spiritual religiosity of the Mesolithic . The interpretation of such finds is controversial (→ prehistoric shamanism ) .

In the past such people were part-time specialists in most regions who otherwise pursued other forms of subsistence . Modern “neo-shamans” (which are only dealt with in passing in this article), on the other hand, are often full-time specialists who actively offer their activities and make a living from it.

Problem of delimitation; Example shaman and priest

As early as the 19th century, the originally Tungus-Siberian term was applied to similar spiritual experts from other cultures. Many authors who have published on concepts of shamanism expanded the term even further. This development has led to the cultural differences being ignored in favor of a generalizing representation, so that it is suggested that there are shamans worldwide in a uniform sense. This is a fallacy that is also denounced by members of different ethnic groups.

For example, the Navajo medicine man called Hataalii is more of a priest and artist: an expert on religion, music, some (not all) ceremonies and the art of sand paintings . The Sioux peoples did not and do not have shamans in the true sense of the word. Since the commercialization of their spiritual traditions through neo-shamanism , they have dissociated themselves vehemently against this term and the abuse by "white shamans".

The fact that in some North American tribes all people went in search of visions and there was no separate expert for it, or that certain hallucinogenic drugs (so-called entheogens ) in South America make almost everyone a shaman, was also ignored in many concepts.

On closer inspection, there are numerous examples of so-called shamans who actually should rather be called priests, healers, sorcerers, magicians, etc. Some anthropologists have therefore suggested that only the indigenous names be used for the respective people in order to end the egalitarianism.

To illustrate the problem, the distinction between shaman and is suitable as priests , as is the mission scientist Paul Hiebert has proposed with his "typology of religious practitioners." Using such schemes, it can then be determined which category a specific specialist is actually to be assigned to. However, the transitions are fluid and therefore such a definition remains model . It should be noted in advance of the following table that traditional necromancers, depending on their cultural affiliation, had other secular functions , since with traditional ethnic groups there was often no separation between everyday life and religion.

| Shaman (as a spiritual specialist) |

priest | |

|---|---|---|

| legitimation | Calling by spirits | Establishment by religious institution, profession |

| authority | Charisma and gift | conferred office dignity |

| Tasks / motivation | Mediation to the transcendent, preservation of tradition | Administration of the religious cult, preservation of tradition |

| Basic activity | makes contact with the transcendent powers for the benefit of the community or individual | approaches the transcendent powers on behalf of the community |

| Reward | In the past, no consideration was given for services to the common good, rarely for private assignments as healers or fortune tellers | regulated forms of different types of remuneration |

| Cult | culturally transmitted, but variable | systematic, fixed |

| Relationship to religion | independent of local religion; Influence on faith possible | depending on the religion represented; no influence on teaching |

| status | independent, respected consultant for his skills | fully dependent representative of a religious institution |

etymology

The German word “Schamane” - which can be found in Germany since the end of the 17th century - as well as the corresponding words in many other European languages (English, Dutch, Danish, Swedish and Norwegian: Shaman , Finnish. : Shamaani , French: Chaman , Italian: Sciamano , Lat .: Šamanis , Polish: Szaman , port .: Xamã , Russian: Šamán, Spanish: Chamán or Hungarian: Sámán ) are mostly borrowed from the Tungus Considered languages , which with the Evenk "Šaman" phonetic corresponds most closely to the derived European forms. The word is used in all Tungusic idioms to mean “someone who is excited, moved, exalted” or “thrashing about”, “crazy” or “burning” . All of these translations relate to the body movements and gestures that Siberian shamans perform during ecstasy. However, a connection with the verb sa , which means “to know, think, understand” is also possible. Accordingly, Šamán could be interpreted as a “ knower ”.

More rarely, “shaman” is etymologically based on the Indian Pali word “śamana” , which means “mendicant monk” or “ascetic”. In this context, some authors suspect an older Indian Buddhist root, which means that the Tungusic word would be a loan word that was adopted by Buddhist Tungus as a term for "pagan magical priests". Friedrich Schlegel was the first to include Sanskrit in the etymology.

Finally, some authors trace the word back to the Chinese sha-men for witch .

In the Turkic-speaking regions of Tuva , Khakassia and Altai , shamans refer to themselves as kham ( khami , gam , cham ). The shaman's chants are called kham-naar . In the course of the Islamization of the Central Asian South, bakshi (from sanskr. Bhikshu ) replaced the native expression kham as a generic term for pre-Islamic religious specialists among many Turkic peoples . Numerous other names for the person of the shaman were regionally limited. (The word kham is possibly related to the concept of the kami spirits or gods, which is central to Japanese Shintoism, which is still strongly shamanic .) Instead of the tungusic Šaman , Mongolian uses the expressions böö (masculine or gender-neutral) and zairan (male, or title for “great” shaman) and udagan for the female shaman.

In relation to the Indians of North America, the term medicine is used differently for the “mysterious, transcendent force behind all visible phenomena” (→ medicine bag or medicine wheel ) . The term medicine man is in fact a literal translation of corresponding terms from various indigenous languages ( e.g. Pejuta Wicaša in Lakota ).

The shaman in the concepts of shamanism

"Shamanism is the complex of beliefs, rites and traditions that are grouped around the shaman and his activities."

In contrast to the general definition of the term, the term “shaman” is viewed in ethnology , religious studies, and social scientists and psychologists in the context of different scientific theories. Various definitions were derived from this, which differ from one another, especially in relation to the specific practices and the socio-economic position of the necromancers of various cultures.

Since the first descriptions of shamans, European ethnologists have tried to recognize similarities and possible patterns and to derive cultural-historical or even neurobiological connections. The resulting scientific concepts are also summarized under the term "shamanism". The Romanian religious scholar Mircea Eliade , to whom esoteric neo-shamanism in particular refers today, is considered to be the pioneer of this concept . However, the validity of his theory and the seriousness of his work is highly controversial in science.

It should be noted that shamanism does not describe the religious ideologies of certain cultures - but abstract, unified models of thought from a European perspective , which primarily compare and classify the spiritual practices of specialists from different origins.

The starting point of the research history of shamanism were the shamans of the Siberian cultural area ( Nenets , Yakuts , Altaians , Buryats , Evenks , European Sami , Japanese Ainu and others). The (classical) definition of the shaman derived from this is:

- Shamans are spiritual specialists who can induce ritual ecstasy when fully conscious and have the impression that their soul is leaving the body and traveling to the hereafter.

There is agreement that this “Siberian type” can also be found in the arctic cultural area of North America . So the person of the Eskimo (ecstasy dominating) "Angakok" is a shaman in the sense of all shamanism concepts (although there were also ritual experts who did not master ecstasy and were still referred to as Angakok). Broad consistence with the inclusion of the (historical) pastoral peoples of Central Asian culture areal ( Kazakhs , Kyrgyz , Mongols and others) and the indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures of northern North America ( Athabaskan , Northwest Coast Indians , Plains Indians and others). Some German authors do not include the shamans of Central and South America, because they use hallucinogenic drugs at their séances or know no ecstasy. Also with the transfer to the Paleosiberians of Northeast Asia ( Chukchi , Koryaks , Itelmens etc.) or to some field farmers of South, East and Southeast Asia ( Nepalese , Tibetans , Koreans , Taiwanese etc.), the hunter peoples of Southeast Asia ( Vedda , Andaman , Orang Asli etc.) and some ethnic groups of Australia were divided from the start. Australian clever men South African Sangoma or West African Babalawos be considered concept shamanism by only a few authors as shamans in the sense of. These authors include Mircea Eliade and Michael Harner , who also include the differentiated medicine people and magicians of Africa and New Guinea - Melanesia . They postulate a “global shamanism” and see in it the original form of every occult tradition (Eliad) or of religion in general (Harner; see there also: core shamanism ).

Such far-reaching interpretations are considered outdated in science today; however, they are still gladly taken up in esoteric neo-shamanism.

Diversity of shamanism

"A preoccupation with shamanism lets us recognize its great fundamental importance for age-old human issues."

The depth psychologist Marie-Louise von Franz unanimously recognized the typical characteristics of highly sensitive people in the spiritual specialists of the peoples .

In very many cultures around the world there are people who in one way or another are reminiscent of the Siberian shamans, but still have to be described very differently. In this respect, taking into account the delimitation problem presented above, one can speak of a “diversity of shamanism”.

Shamans

Depending on the ethnicity, there are both male and female shamans; sometimes both are valued equally. Where priestly offices in the high religions were or are only accessible to men, female shamans from the common population occupy the lower sacred ranks and exercise the traditional popular religious functions there. They are seldom consulted by men because they are involved in pagan and superstitious rituals. With their traditional knowledge of medicinal herbs , women mainly served basic medical care, treated mainly minor illnesses and performed the office of obstetricians (see also: Witch ) . Among the peoples of classical shamanism in Asia and North America, they lost their ability to shamans during pregnancy up to several years after giving birth . Often they only became shamans after menopause , especially since they were subject to numerous taboos on purity during menstruation .

In the Tsar and Bori cults of Northeast Africa, where the worship of pre-Islamic deities is continued, especially in the old house states - i.e. in the context of the high religions Islam and Christianity there - female shamans are preferred, as is the Afro-American obsession cults of the Caribbean and Brazil ( e.g. Voodoo , María Lionza cult , Umbanda , Santería , Candomblé etc.).

Functions and social significance

The spiritual specialists are granted special knowledge and abilities of healing and divination as well as various magical powers, knowledge and wisdom that other people do not have. He or she used to serve the community as a shepherd of souls for most ethnic groups and specifically acted as a doctor and spiritual healer , fortune teller , dream interpreter , military advisor, sacrificial priest , guide of the dead souls , weather magician , master of ceremonies for fertility and hunting rituals, spirit medium , investigator in matters Damaging sorcery , a teacher or sometimes just as an entertainer. The more complex the social structure , the more differently specialized shamans there were.

He is also responsible for the harmonious relationship between the group and the environment, provided that they are still “ ecosystem people ” who have little contact with modern civilizations. In this case, the shamans are also the strict custodians of traditions , ancestral knowledge , moral norms and myths . The French anthropologist Roberte Hamayon considers this to be the central function of the Siberian shaman, as he regularly performs rituals once a year for the acquisition or production of happiness - in the sense of hunting luck, the well-being of the community and especially the regeneration of life - regardless of random events . performed. The group members were encouraged to play, dance and sing, which, according to Hamayon, should strengthen the hope for the reproduction of the group and natural resources. These rituals were performed along with the initiations of new shamans.

The most common use in most cultures is certainly the treatment of illnesses in which medicinal and herbalists - today also modern doctors - no longer know what to do. The shaman describes his activity as "questioning the spirits " in order to find out from them the cause of the illness and the type of treatment. In the religions of traditionally natural ethnic groups without written book religions and missionary influences, the general idea prevails that there is a supernatural world of spirits that influences everyday life (see also: animism , animatism , animalism , fetishism ) . If such people feel that something is no longer in balance or if they need assistance for the future, the spiritual specialist is asked to contact the forces of this “otherworld”.

The effective radius of the shamans depended on nomadic ethnic groups closely related to the lineage together: The more distant the family relationship was, the more likely a shaman declined to assist. In peasant cultures, however, this was no longer important.

The status of a shaman was high in Asia and America. He was one of the most respected people and is still revered with fearful awe among some ethnic groups because of his magical abilities. The loss of a necromancer used to be a cause of great concern among people. Shamans, however, had little political influence. In a sense, they stood “above” society; were "out of this world". Occasionally their prophetic and magical gifts were in demand during armed conflicts. In medieval court shamanism in Central Asia (for example with Genghis Khan ) the shamans were appointed close advisers of the khan - who were endowed with the appropriate power. This influence persisted in various ways into the 19th century.

Despite their prestigious position, necromancers used to be required to offer a high level of sacrifice, selflessness and self-discipline. His reputation depended solely on the success of his activities. In addition, he felt dependent on the spirit world, which, according to his belief, severely punishes any failure: Ethnographic records report the loss of spiritual abilities, from madness to death. With some North American Indians, a shaman could be killed in ancient times after several unsuccessful attempts at healing.

Shaman's skills

In most of the non-scripted cultures in America, Asia and Australia, shamans and similar necromancers were custodians of knowledge, rites and myths and therefore had to have particularly good memories.

In many parts of the world, skills such as ventriloquism , sleight of hand and creating illusions are an indispensable part of the shamanic ritual. In Siberia and Canada, for example, the tent was secretly shaken to signal the arrival of the spirits, and South American medicine men create the impression that they are pulling fragments of bones, pebbles or beetles from a patient's body. Such practices should not simply be condemned as pointless hocus-pocus or even fraud (as Soviet authorities have done for a long time), because they serve to astonish the patient and thus consciously or unconsciously fully affect the ceremony and the healer adjust. According to Marvin Harris, this is an essential prerequisite for the success of the treatment.

In some cultures, people believed that they could have enormous abilities: Arctic peoples, for example, believe that the shaman can bring back the souls of animals that have become rare and then scatter them across the country. South American Indians believed in a magical influence on the hunted prey: the shaman banished the game so that it could be captured more easily. In many countries people believed in weather magic, especially in Africa or in the arid regions of North America.

According to Ervin László (philosopher of science and systems theorist ), many shamans have telepathic communication skills that enable them to "see" events that are far away. The Lakota shaman Black Elk (1863–1950), for example, reported on a “spirit journey” while he was in Paris, during which he “saw” developments in his people that prompted him to return home. The ethnologist Adolphus Peter Elkin was even of the opinion, based on his research with the Aborigines, that telepathy was possibly quite common among so-called " primitive peoples ".

Visionary experiences that are experienced as contact with the spirit world of the transcendent hereafter define the spiritual specialist in many cultures. Because of these mental abilities, shamans are sometimes referred to as "pioneers of consciousness research". In this context, the cultural anthropologist Felicitas Goodman recognized in a cross- cultural study that so-called “ritual postures” in connection with rhythmic noises are used in all cultures around the world in order to embark on a “soul journey”.

Shamanic soul journeys

→ Main article: The ritual ecstasy (in the article Shamanism)

The contact with the spirit world is described by many peoples as a journey of the soul or the hereafter, as a magical flight into another space- and timeless world, in which man and the cosmos form a unity, so that one can find answers and insights that cannot be reached through normal perception are. Even if the places of this journey and the spirits are only imagined , the experience of this inner dimension is extremely real and highly conscious for the shaman. Moreover, in this way they do things that seem like miracles and that keep baffling science.

In the imagination of traditional people, experiencing a journey to the hereafter corresponded to the dreams of ordinary people, but consciously brought about and controlled. This idea fits very well with the modern explanation of such phenomena:

From a neuropsychological point of view, there are different forms of expanded states of consciousness : lucid dreams (e.g. with Amazon tribes); visionary intoxication caused by entheogenic-hallucinogenic drugs such as tobacco in North America, peyote in Mexico or ayahuasca in the Andean region, which evoke spiritual experiences (so-called entheogens ) ; or about trance and / or ecstasy as with Siberian and Central Asian peoples and many other groups in Asia.

The so-called “ecstatic trance” is part of the shamanic repertoire in many cultures, but is “not a universally widespread phenomenon”, as many shamanic concepts suggest. At the same time, there is a very deep relaxation as in deep sleep, maximum concentration as in awake awareness and a particularly impressive pictorial experience as in a dream. The shaman always experiences this extraordinary mental state as a real event that apparently takes place outside of his mind. Sometimes he sees himself from the outside (out-of- body experience ), similar to what is reported in near-death experiences . As we know today, man has direct access to the unconscious in this state : The hallucinated spirits arise from the instinctive archetypes of the human psyche; the ability to grasp connections intuitively - i.e. without rational thinking - is fully developed and often expresses itself in visions , which are then interpreted against one's own religious background.

In order to achieve such states, certain formulas, ritual acts and mental techniques are used depending on the cultural affiliation : These are, for example, burning incense , beating certain rhythms on special ceremonial drums , dance ( trance dance ), singing, asceticism , isolation, ingestion of psychedelic ones Drugs , fasting , sweating, breathing techniques, meditation , experiencing pain or looking for visions . It is particularly important to adopt certain “ritual postures”, as the studies by Felicitas Goodman show. During the séance , shamans in many regions are still able to communicate with those present, ask questions and give directions. By contrast, in Africa, the magicians, sorcerers, healers, etc. getting into a state of obsession , where their will is completely prevented.

The training of such ecstatic trance states has extremely positive effects on the shamans themselves: energy, self-confidence, all cognitive abilities (especially concentration and perception), body awareness and wholeness experience increase significantly, so that authentic and charismatic personalities mature.

Healing art

Another central function of most shamans was that of the highest ranking healer. There were minor ailments caused, of course, that did not require necromancy. However, depending on the culture, serious, protracted or mental illnesses were allegedly based on harmful magic, soul theft, possession by ghosts, but also on taboos or neglect of ancestors.

In contrast to modern medicine, the spiritual healing art was a complex, interactive and above all holistic healing art that went far beyond the purely medical treatment: It was a service for the existential "salvation" of the fellow human being: a comprehensive care up to social aspects with regard to the effects on the relatives, even on the entire community.

Each culture had its particular healing rituals. Herbal healing was mostly combined with the help of spirits, or the "spirits of herbs" - which were also considered to be animated - directly brought about. Often pathogenic “foreign substances” were (allegedly) sucked out with the mouth and then spat out, sometimes with tubes (without injuring the skin) or they were removed with a quick movement of the hands. In America, the area was previously massaged with saliva or smoke. If the cause was evidently an “evil spirit”, a kind of exorcism with a lot of noise and ceremonial movement took place. If the “free soul” of man was thought to be lost, the shaman went on a search in the spirit world in order to bring the soul back and then to blow it back in. Today we would call such diseases post-traumatic stress disorder , dissociation or psychosis .

As doctors keep finding out, shamans can demonstrate considerable success with such mental illnesses, but also with physical ailments such as rheumatism and migraines . The placebo effect is usually used as an explanation , the effect of which offers possibilities for healing.

In some tribal societies , the roles of the shaman and the medicine man are separate, as is the case with the North American prairie Indians. While the shaman invokes spirits, the medicine man rather relies on knowledge and experience with remedies and surgical interventions, whereby the healing of the sick is promoted by protective spirits.

Shaman practice

In the past, necromancy was always “important community experience in the service of group solidarity”, because those present took an active part in it in various ways, for example repeating the shaman's words, incantations and songs. In his battles in the afterlife they cheered him on, but also enjoyed the theatricality of his magical ideas, which they were well aware of. Some classical shamans used language incomprehensible to laypeople, thereby adding to the magic of the situation.

The commissioning of a spiritual specialist is associated with certain rules and rituals in the cultures concerned. For example, the objects of Siberian shamans must not be touched. For healing the sick and divination get a lot for a fee, traditionally in the form of services or in kind . The wages are usually rather low and were, for example, “determined by the spirits” among the peoples of Central Asia. For some South American Indians, however, the shamans were paid high prices. In Siberia, shamans had to forego payment entirely and often became impoverished.

The place and time of a shaman session also differs from culture to culture, but often has cosmologically based peculiarities. In Siberian shaman's tents or rooms, for example, there is a tree as a representative of the world tree . In Southeast Asia the séances take place in separate consecration areas of the shaman's dwelling or small temples. In some cultures, night sessions are preferred as the night is considered ghost time. Idol figures - e.g. B. with representations of ancestors or animal spirits, the "guardian figures" of the African religions - sometimes have important functions.

Costumes and props

Certain artifacts in connection with the journey to the hereafter play an important role in shaman sessions . These symbols reflect the ideas about the structure of the cosmos and are different for the individual peoples.

The shamans of North and Central Asia as well as the Inuit in Greenland and Canada sometimes still wear a special costume that sets them apart from the rest of the people. With them it is closely related to the respective guardian spirit addressed during the action , so it must also be changed when it changes. Sometimes, together with a mostly anthropomorphic mask, it fulfills a metaphysical and identifying function in the sense of the protective spirit involved, with which the shaman merges into a "double being". These masks are more common among shamans in the syncretistic high religions of Asia and there also have zoomorphic features.

Two basic costumes were found in Siberia: the bird and the deer type , depending on the animal spirit preferred. Both costumes were used side by side, depending on the sphere of movement that was to be used on the journey to the hereafter, i.e. air or ground. The costume included a belt, bells, a perforated metal disc for the descent into the underworld, as well as several metal discs on the chest and back, as well as numerous elongated iron plates for steeling and protecting the body. The historical Noajden of the Sami wore their clothes turned inside out. The production of such costumes was also carried out under strict rules (at certain times of the year, by certain people, etc.) due to their strictly ritual and magical character. It was usually made from the fur or plumage of a certain animal, identifiable by precise features (such as a white spot on the forehead), which the shaman had seen in a dream and whose discovery and hunt could take months. After completion, the costume had to be ritually cleaned and consecrated.

Sometimes the face was disguised or blackened and the hair was not allowed to be cut in order not to lose vital force. Antler crowns were common for some Siberian and Central Asian ethnic groups. In other areas headgear was also worn, in America and Africa mostly feather bonnets.

A variety of different props are used in shamanic practice. Like traditional costumes, they also have magical functions. They are specific to different ethnic groups: For example, ladders that South American shamans use to ascend to the upper world; Bundles of leaves and rattles, which in some North American tribes are supposed to make the voices of the helping spirits audible, or feathers, stones, bones in sachets and medicine bags . Twigs, brooms, whips, knives and daggers that ward off evil spirits in Inner Asia; Swords, bells and mirrors in Southeast Asia, etc. Ceremonial staffs are used throughout Asia, which in Siberia are considered to be the image of the world tree.

Of particular importance is the shaman's drum , which is used throughout Asia (but less often in tropical regions), in North America and by the Mapuche of South America and contains a variety of cosmic symbolism, some of which vary from area to area, as well as an important role on the way to the Trance plays.

The use of entheogenic drugs occurs mainly in southern North America, in Central and South America: These are mainly tobacco , peyote, Andean cactus ("San Pedro"), ayahuasca , datura ( thorn apple ), sky-blue morning glory , Aztec sage ("fortune telling." -Sage ") or mushrooms containing psilocybin . In the area of northern Eurasian shamanism, the fly agaric was used as an intoxicant . Various hallucinogenic drugs were also used in Central and Southeast Asia. Iboga was used in Africa and cannabis mainly in southern Asia.

The "classical" shamans of Siberia and Central Asia

Although the term "shamanism" as well as many popular scientific treatises suggest to the layman that it is a uniform, historically developed ideology or religion, at least the term "classical shamanism" from Siberia and Central Asia is also used by some scientists of the 21st century as Name used for the original religion (s) of these cultural areas. But even here, despite obvious similarities, shamanism was by no means a uniform phenomenon!

Part of the classical shamanic cosmology was the concept of the hereafter of a multi-layered cosmos made up of three or more levels, populated with benevolent and ill-willed spirits and connected by a world axis . The soul was seen as an entity independent of the body , which can travel to the spirit world on this axis with the help of animal spirits (→ totemism ) .

The ritual ecstasy was and is the central element of classical shamanism. This creates the real experienced as imagination a mental flight (the shamans flight , so ). Both the journey and the "spirits" are consciously brought about and controlled by the shaman in contrast to dreaming. Shaman's flights to the most powerful “beings” within the shamanic cosmologies - such as the gods (with shepherd nomads or field farmers ) or the “ lord or mistress of animals ” (with hunters ) - were given to him.

The social function of the classical Nordic shaman was different from that of a priest , because in contrast to this he wore - in the words K. Ju. Solov'evas - a “high responsibility for his group. In his community ( clan , tribe ) he was seen as a mediator between this world and the hereafter. He was able to interpret the signals of nature, of which people understood themselves to be part. Because illnesses or the absence of game were interpreted as a result of human error, it was the shaman's task to explore the cause, to find a balance and to influence the uncontrollable forces of nature through appropriate behavior. In the shamanic séance ritual [Siberia] - the "camlanie" - the shaman traveled to other worlds as the embodiment of his group and stood up for their fate there. Supported by helping spirits, he sought advice there in order to make the right decisions for the individual as well as for the group. "

There is much speculation about the age and the origin of classical shamanism . It is daring to relocate its origins to the Upper Paleolithic using a few illustrations and artifacts . While some elements come from the hunters' environment, others point to agrarian societies. In addition, influences from high Asian religions (especially Buddhism) can be proven.

From the vocation to the transformation into a shaman

The entire process of “becoming a shaman” took place in several stages for all peoples of Siberia, which stretched over a long period of time and could sometimes contain life-threatening elements.

When adolescents displayed socially, psychologically or health-related behavior (self-chosen isolation, irritability, savagery, epilepsy-like seizures, fainting, long absences in the wilderness, depression, etc.) and often had a shaman among their ancestors the conditions are given to be "called by the spirits". It was not uncommon for this to happen against their will. The specific cultural expectations of the community and the unshakable belief in the traditional myths usually gave the chosen ones the impression of a fateful development over which they believed they had no influence: They experienced how their conspicuous behavior led them into a personal crisis and finally, an unpredictable event - a dream, a vision, a lightning strike, etc. - or the social pressure made you feel called. If this strongly suggestive event resulted in the adept's spontaneous “recovery” (→ placebo response ) , the “truth” of fate was evidently confirmed.

Some authors see shamanism as a way of social integration of the mentally ill (e.g. Georges Devereux ). However, it is precisely the healing of such "abnormalities" in oneself that is a prerequisite or initiation for a shaman career, so that such illnesses do not belong to the essence of the trained shaman.

education

The shaman training included phases in which the adept separated himself from other people in order to learn the soul journeys and to optimize the technique and control of events more and more. He experienced this as “instruction by auxiliary spirits”, which mostly appeared to him in animal form.

In some Siberian cultures, training by a teacher was preceded by a special, usually three-day “shaman initiation” by the spirit powers. The apprentices experienced this as the loss of their previous identity, as they were kidnapped by the spirits into the underworld, there, dismembered, eaten and reassembled and finally taught (compare: Dema deity ).

The actual training and initiation could be accompanied by an elderly shaman, who taught the apprentice the techniques to move safely in the spirit world. The acquisition of traditional knowledge was another educational goal. The teacher instructed him in all aspects of medicine as well as in the traditional formalities, prayers, chants, dances, etc. At the end of the three to five year training (which lasted up to twelve years for the Greenland Inuit) was the ordination of the shaman.

During the formal ordination ritual, the young Siberian shaman had to publicly demonstrate his skills. The main purpose of the ritual was to bind him closely to the social community, in which from then on he assumed a responsible position with high character requirements. With the Central Asian peoples in the sphere of influence of the high religions, the ritual was very complicated and similar to a priestly ordination .

Often the shaman was then formally recognized by the elders of the community. At the same time, his helping spirits were sacrificed.

Traditional contemporary spiritual specialists in the light of history

Since the beginning of colonialism and the associated Christianization , shamans in particular, as representatives of indigenous world views, have been subjected to persecution. In Stalinism , according to Christoph Schmidt, shamans were not only suppressed because of their supposed backwardness, but also because they were counted as self-employed in the upper class. It was not until the end of the 20th century that they were rehabilitated as part of the global New Age movement and with reference to the works of Eliade and Harner.

However, a drastic change in culture - oppression, proselytizing , re-education and the general turn to the modern world - has fundamentally changed the shamans and their social position. Although the centuries of ostracism (including by the Christian churches such as today in Nunavut ) in many parts of the world led to shamanic shamanism only in secret and to keep silent about it, shamanic knowledge is today highly fragmented or largely already forgotten devices. Therefore, the majority of necromancers can no longer fall back on complete traditions, but are dependent on ethnographic records from European researchers or make use of western neo-shamans, whose supposedly "ancient traditional wisdom" is often a colorful mixture of appropriately selected ones that are torn from the cultural context and pseudo-traditions cleverly combined with “esoteric fantasy”.

The neo-pagan currents of neo-shamanism and neo-paganism in this form have had a considerable influence on many traditional shamans and have permanently changed them, so that the reference to ancient traditions is increasingly questionable. This applies in particular to the largely assimilated peoples of North America and Siberia or Australia, but is even documented for local communities whose traditions have so far been considered to be somewhat intact (e.g. Anishinabe, Yupik , Chanten).

Most modern indigenous shamans today work predominantly as healers in competition with doctors and self-appointed spiritual healers or as "pastors". Only in very few remote communities, where people are still largely self-sufficient in the way of life of their ancestors, does the shaman still have an existential meaning for the community.

Eurasia

Eastern Europe

Although there have been no shamans in the classical sense in Europe - apart from the reindeer herders in northwestern Russia - for centuries, in some Eastern European countries you can still find people whose work is reminiscent of earlier shamanism.

In Bulgaria, even young people consult a baba ("grandmother", but here with reference to the sorceress Baba Jaga ) for some illnesses , who - similar to the earlier witches of northern and western Europe - are herbalists and are trusted to have magical abilities. In the 1970s and 80s, the Baba Wanga achieved great fame across the country for her (alleged) clairvoyant abilities. She was also able to heal.

The situation is even clearer in Hungary, where many people have been seeking advice and help from the Táltos since ancient times , who mainly work in trance and their services as seers , chiropractors , spiritual healers, herbalists , naturopaths or necromancers even after centuries of difficult political and religious problems Circumstances are still present today. The shamanic legacy of the Urals ancestors (relationship to the Sami and Nenets) is evident here.

Siberia and Central Asia

In the 17th century shamans were burned in Norway (in connection with the witch hunt ) and in Siberia. They were later punished like felons in Scandinavia and Russia and their props destroyed. Nevertheless, since the 18th century, Siberian Russians were sometimes fascinated by the shamanic career. As a result of the communist October Revolution , shamans were considered charlatans or reactionaries in the Soviet Union and were accordingly denounced or persecuted. At the same time, forced collectivization , mass immigration and industrialization as well as a boarding system undermined the livelihoods of traditional indigenous cultures and thus of shamanism. The Hezhen shamans in the Far East responded to the persecution by focusing their activities on treating the sick. Others continued to work underground.

The original shaman culture could only survive in very few groups of the small peoples of Siberia - who still live relatively isolated in the wilderness (especially documented for the Chanten , Keten , Tuvins , Jukagirs , Chukchi and Niwchen ). The chants were able to hide and preserve their traditions deep in the taiga and still react very carefully to questions about their shamans and rituals.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union there has been a revitalization of shamanism among most peoples. Even the Sámi , whose religion has been extinct since the middle of the 19th century, have a Noajd again in Ailo Gaup from Oslo, who, however, has to fall back on the traditions of foreign peoples.

The development in China's Maoist history was similar. But even there, especially in the north of Inner Mongolia , in Xinjiang with the Islamic Uyghurs and in Tibet with the Buddhist Changpa , a syncretistic shamanism has partly survived and is now tolerated by the government. The same applies to the small pastoral nomadic people of the Yugur in the Gansu province . In the poor villages of northern Manchuria , Dauris - and in southern Manchuria shamans of the Khortsin-Mongols survived the period of communist rule relatively well and still perform many functions today.

However, nowhere in Eurasia can one speak of a real renaissance of shamanism, because the break in time led to a considerably smaller number of shamans and a decline in the traditional knowledge that could be passed on to future shamans. This is also associated with a general cultural change in times of globalization , the consequences of which can be clearly seen in the current situation of the still lively shamanism in South Korea, where the loss of tradition is paired with the emergence of new forms and contents. However, the “urban shamans” of Korea and Japan have been integrated into the state cultures for centuries and therefore cannot be compared with the indigenous cultures in terms of their social functions.

It is still difficult to say to what extent a real revival will take place in Siberia and Central Asia despite the new freedom. Even the relatively well-preserved shamanism of the Tuvins in southern Siberia is changing drastically through intensive contacts with the neo- shamanistic scene, possibly in a direction that will soon have nothing in common with the original traditions of this people. The German-speaking writer and Tuva shaman Galsan Tschinag is a well-known representative of this development.

The other modern shamans of Russia often live in cities, have a secular education or a university degree, hold certificates, offer their services in shaman centers, socialize with tourists and are used as symbols of a post-socialist national identity.

In the Islamic states of Central Asia one can find dervishes who use the trance dance to get close to Allah in ecstasy and various types of spiritual healers - but they are not shamans in the ethnological sense . However, their activities go back to the influence of classical shamanism, which the ethnologist Klaus E. Müller attested to the pastoral nomads of the steppe regions of Kazakhstan and historical Turkestan until the beginning of modern times. Only in some groups of the Kalasha in Pakistan's Hindu Kush has - despite forcible in the 19th century and is still taking place persecution by violent Islamists - a polytheistic faith and Schmanentum ( Dehar ) can get.

The urban shamans of Korea

Siberian shamanism influenced the emergence of the folk religion in Korea , one of the ancient states of East Asia.

Characteristic for this is the belief in an all-embracing, omnipresent spirit, with which shamans, known as “Mudang” in South Korea, can make contact as a medium; "Baksoo Mudang", male shamans, are rather rare. Korean shamans are considered to be in the lower class and are often involved in financial or marriage matters. The office of shaman is either hereditary or obtained through special skills. At the center of Korean shamanism is the kut with the shaman priestess, the shamanic ceremony that often lasts several days, but has largely lost its social relevance and is largely limited to the family sphere. The ceremony is ecstatic. Archaeological finds from royal tombs indicate that the rulers themselves exercised this office in pre-Buddhist times. Later on, Buddhism and Confucianism, along with ecstasy, the neglect of women and cosmic religiosity in conjunction with a rigid ceremony, shaped the Korean world of belief.

Japan's Shinto shamans

Shamans are also still part of Shintoism in Japan ( Kamisama : Otoko miko or Onoko kannaki for male, Onna miko , Kannaki or Joshuku for female; and many other terms). You are contacted to free people from the influence of evil spirits.

Japan's shamanism appears to be a mix of Siberian and Korean and Southeast Asian shamanism. The oldest reference to shamanism in Japan can be found in Kojiki , a work that was written around the year 700 AD at the Japanese imperial court. With the introduction of Buddhism, the female onna miko was institutionalized as an assistant to the Shinto priest. Only in their initiation ritual is there still a shamanistic element. In contrast, there is the living tradition of Itako in northern Japan and Yuta in Okinawa : Often it is blind women who practice independently and independently. Japan is known for its numerous new religions , which have emerged in different waves since the 19th century. The so-called "neo-new religions" (after 1970) often emerged from a resentment against modernity and are again based more strongly on old magical-religious ideas. Many religious founders - the majority were women - experienced their initiation as a state of trance in which a kami revealed itself to them as a personal protective deity. They received revelations about the future of the world and often the power to heal illnesses. With regard to shamanism, this applies in particular to the Amami Islands : The traditional religious ideas are preserved today by a syncretic popular belief, the elements of Noro (priest) cult, Yuta (shamanism), Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, Shintoism and to a lesser extent Catholicism. The yutatum is understood as the “main actor of the magical-religious complex” and is viewed by some authors as real shamanism.

South asia

In the transition area between the Buddhist-influenced shepherd cultures of Central Asia and the Hindu farmers of the Indian subcontinent, some Himalayan mountain peoples have shamanic traditions. This is documented, for example, for the Dakpa (Monba) in Bhutan.

The Adivasi are the bearers of the most original (and diverse) folk religions of India : mostly syncretistic mixtures of Hinduism and animism, in which there are sometimes shamans or shaman-like experts. These specialists are still present in the groups that still live traditionally today.

The Bhil are among the largest of these ethnic groups (West and Central India, approx. 3.8 million members). At the center of their religious life are the barwo , who function as magicians and medicine men. There are also male and female pando who are appointed to their office by a guru . The barwo is a healer and performs sacred ceremonies, which include sacrifices in the context of life cycles and ancestor worship.

Other Adivasi, in which various forms of necromancer still occur at present, are the Naga and the ( Aimol-Kuki ) in the monsoon forests of the extreme northwest, the Chenchu in Andhra Pradesh , the Aranadan in Kerala and the Birhor in northeast India, the Saora in eastern India, the Raika , the Gond in Gondwana and the Gadaba in central India.

Among the Wedda (indigenous people of Sri Lanka) there are the Kapurale and Dugganawa , who are the contact persons to the spirits of the dead who speak through the mouth of the conjurer.

South East Asia

In Southeast Asia the forms of ghost specialists are extremely diverse and lively. A distinction must be made here between two different "shaman cultures": the animistic-ethnic minorities , which in turn (blurred, as often both) are subdivided into the predominantly wild-hunting peoples and the shifting field farmers , as well as the various ritual specialists of the majority populations in the individual States.

Similar to South America, there are still some mountain and rainforest peoples in Southeast Asia who have hardly been contacted or who stick to their traditional way of life. Except for the indigenous inhabitants of some islands of the Andamans ( Sentinelese , whose shamans are called "dreamers" (Oko-jumu) ) and Nicobars ( Shompen : Menluāna are called the male and female shamans) in the Bay of Bengal, their isolation from the Indian State is protected, the influence of the modern world and the decay of traditions are already visible in many ways. Nevertheless, shamanism has been preserved quite well with many local hunters, fishermen, gatherers and shifting farmers in the region.

In China, the Derung live on the border with Myanmar, the Yao on the border with Vietnam and the Akha in Laos , all three of whom still have traditional shamans.

In Vietnam , which is mainly Buddhist and Catholic, there are still city shamans (dong) who perform various rituals of sacrifice and inspiration in the originally Confucianist folk religions Đạo Mẫu and Cao Đài . The Lên đồng ritual , in which the shaman asks the spirits in a trance for health and prosperity for the hosts of the ritual, is particularly popular with all Vietnamese regardless of their denomination . The costume plays an important role here: It reflects the classic court costume of the premodern and is “attracted” to the spirit in order to honor it in this way. The spirit then contacts those present through the medium to receive offerings and enjoy the music.

In Malaysia and Indonesia, numerous smaller rainforest ethnic groups still follow strongly animistic religions, including shamans. In the orang-asli groups of southern Thailand ( Mani ) and especially Malaysia there are medicine men (Pawang, Saatih, Kemantan) who call for help from spirits and perform ecstatic ceremonies and shamanic initiation rites . Shamanism is particularly strong among the Sakai and Jakun (shamans: Hala and Poyang ), somewhat less so among the Semang (Halaa) . The rites differ considerably in the details, but follow a common basic pattern: incense, dance, music and drumming are standard rituals. Summoning of auxiliary spirits and soul travel are common, as is dream interpretation. Shamans have high status even in death. Central here, as with the Indonesian rainforest peoples, is the evocation of the tiger spirit, which makes the shamans - but also every person who makes an effort - possessed (lupa) .

In Indonesia the "great shaman" is conjured up in the form of the tiger spirit, the incarnation of the mythical ancestors and thus of their own origin. The Sumatra Batak priest Datu also has a high social position and, in contrast to the actual shaman called Sibaso , does not fall into a trance. As in other ethnic groups, there is a division of personnel in terms of functions. Priestesses play the main role in the Dusun , a Dayak group in Borneo . The Dayak, one of the largest indigenous groups in Borneo, also know two types of magicians, but both perform ecstasy rites. But here the differences between the individual subgroups are sometimes considerable and range up to the sexless shaman priests (Tukang sangiang) of the Ngaju rice farmers. The shaman boat plays a particularly important role in the Malay archipelago , a concept that can be found in a similar way in Japan or Melanesia . The shamans of the Mentawai West Sumatra, who are the only ones allowed to perform the ritual dances of the people, belong to the hunter type

Spiritual healers who go back to animistic-shamanic traditions are documented for Java and Bali . On the Internet today you can find numerous Balinese healers who call themselves shamans and offer all services (also in German) from healing to fortune telling to love magic.

Shamans are still documented for the Aeta of Luzon and the Palawan Batak in the Philippines .

America

North America to North Mexico

In North America there has been a mostly intensive mixing of ethnic religions with Christianity. Since the last quarter of the 20th century, however, the old worlds of belief and some spiritual practices have experienced a renaissance together with the Indian self-confidence - even if only with a folkloric background. Some Indian peoples still have medicine men to maintain the ritual culture as well as in the context of a partial re-indigenization - their original role in these cultures, however, is history.

Only in isolated groups of Alaska, Canada and Greenland ( East Greenland Inuit , Indians of the Subarctic ) and Mexico, who at least partially managed to preserve their traditional way of life despite Christianization and "westernization", do the shamans still have some of their original social functions.

For the religious feeling of the Eskimos the overwhelming feeling of fear was characteristic in the past: a feeling of being dependent on supernatural powers. The all-animating magical power of Inua reigned in this continuum . In order to protect themselves from the innumerable spirits that one imagined everywhere in nature, the Eskimos developed a large number of taboos . Although almost all Eskimos are Christians today, such deeply entrenched cultural fears will not disappear in a few generations, especially outside of the larger settlements, where the traditional way of life is still important for small groups. There continue to exist traditional shamans ( angakok , plural angakut ) who function as healers, pastors, guardians of hunting morality and directors of numerous festivals and ceremonies, as evidenced by the Yupik and some small Inuit communities of Nunavut. The same applies analogously to a few local groups of the East Greenland Inuit and the sub-Arctic Indians who still live in largely wild-based subsistence farming in the taiga and tundra. Groups of the Gwich'in , Nabesna, Dogrib , South-Slavey and Beaver, Chipewyan , Dakelh , Anishinabe and Innu are documented here (roughly from west to east) . According to field researcher Jean-Guy Goulet, the South Slavey groups of the Dene Tha are said to have succeeded in preserving their traditional belief system by integrating Christian symbols without, however, changing the core of the religion. The source of information here is the traditional “dreamer” Alexis Seniantha. In the Athapaskan languages the medicine man was called Deyenenh (Nabesna) or Díge'jon (Dogrib) and in the Algonquian languages Maskihkiwiyiniwiw (Cree) Nenaandawiiwejig (Anishinabe) or Powwow ( Narraganset ).

Outside of the north, the cultural area of the southwest and neighboring Mexico, medicine people either only appear as conductors of ceremonies (sometimes with ritual healings) in traditional rituals (for example in the sun dance of the prairie Indians or in the Iroquois medicine associations ); or they have established themselves in the neo-shamanistic scene - which, however, mainly appeals to whites. Also known in Germany is "Sun Bear" ( Vincent LaDuke ), an Anishinabe Indian who tried to combine the spirituality of different tribes into one Indian belief. Such shamans - who not infrequently also stand up for the rights of their peoples in public - are in any case important "cultural mediators" in a globalized world. Often, however, these forms of spiritual specialization have very little in common with the traditional traditions of individual ethnic groups and are adapted to the needs and wishes of modern people. A well-known representative of these so-called "plastic shamans" is Dancing Thunder.

Some pueblo tribes of the southwest have managed to preserve their complex ceremonial system to this day. It aimed at potential life crises and their overcoming through rites, in which shaman-like priestly brotherhoods (without ecstasy) also play a role. From this region and Mexico comes the use of the hallucinogenic drug peyote, which today plays a crucial role in the Native American Church . Further north, the shamans only used tobacco as a drug, if at all .

Almost all of the North Mexican Indians are formally Catholics. Nevertheless, there is still the herbal and spiritual healer called curandero , which is practically throughout the entire Ibero-American area. In addition, the belief in witchcraft is still widespread. Most of the so-called shamans are part of modern neo-shamanism, because the religions of the advanced civilizations of the Aztecs and their neighbors used to be characterized by a complex priesthood without shamans.

Traditional shamans still exist mainly among the following two ethnic groups, who have been able to preserve large parts of their indigenous religions:

Tarahumara Northern Mexico: Until a few years ago they were the largest ethnic group in Northern Mexico. The Catholic Church never penetrated the beliefs there very deeply with its ideas, but its rituals (such as waving incense) seem to have impressed the Tarahumara, because now part of the Catholic ritual is in shamanic hands. The shaman, called ewe-ame , continues to exercise his traditional functions, heals the sick and uses peyote to hold or bring back the lost or fleeing soul of a sick person, works against witchcraft and has an almost semi-divine status.

Huichol : Your Marakame medicine men called because of their abilities and their power in the peoples of the Sierra Madre Occidental famous. The Huichol religion still contains most of the pre-Columbian elements among Mexico's indigenous people.

Meso and South America

In Meso and especially in South America , the situation is different: Shamanic practices in healing magic and sorcery are still widespread, although here, too, in the many already evangelized tribes, the necromancers only carry out parts of their original activities and their position is therefore significantly degraded is.

A major difference between the North and South American specialists is the intensive use of psychotropic drugs in South America. Central America forms a transition zone, in North America this custom is - if at all - only weakly developed and preferably limited to tobacco . Especially in South America, the use of such drugs makes almost everyone a potential medium, as they make it very easy to achieve trance-like states. The liana drug ayahuasca , for example, is consumed by most adults among the Urarina in the Peruvian Amazonia or the Shuar of Ecuador. The trance is very strong and is often mistaken for the only real world.

In contrast to the Aztec descendants, the lowland Maya ( Lacandons ) of Guatemala and the Talamanca tribes of Costa Rica traditionally have spiritual necromancers. Today, however, their functions are partly influenced by Catholicism.

The Chocó Indians in Panama were able to maintain their way of life because they avoided contact with the Europeans for a very long time and withdrew into the depths of the forests. They still practice magical healing and other shamanic customs today, similar to the numerous isolated tribes scattered in the Amazon rainforest. There are still necromancers among the Kuna Panamas. They act as clairvoyants and can penetrate the underworld in a trance.

For many of the isolated peoples in Amazonia and the Mato Grosso, the respective spiritual-religious expertise is likely to still exist unchanged. The Christian missionaries - above all the Evangelicals from North America - still put a lot of energy into the abolition of ethnic religions and thus also of the medicine people (even against existing state bans).

The basic elements of the lowland religions of South America are animistic, that is, the world is populated by good and bad spirits, souls, witches, wizards, etc. They can cause harm if rituals and moral principles are not properly followed. Signs, amulets and dreams are very important. People believe that they can transform themselves into animals and thus deprive others of life force. Hence, their well-being depends on the control of innumerable supernatural powers. Universal harmony must be preserved through guided rites or collective ceremonies. This is guaranteed by the medicine man, who is not least a master of transformation. It is made possible by the ecstatic rapture. Stimulants and narcotics such as tobacco, alcohol or coca leaves are of the greatest importance for the rainforest Indians, as are stronger hallucinogens , which, like the ayahuasca obtained from a type of liana, are sometimes regarded as divine and are mainly used in the Amazon- Orinoco area. Some of them are reserved for experts, but in some peoples they - and the magical practices that go with them - are used by everyone. The spiritual specialist is usually highly regarded. He rarely has the function of a religious cult administrator. Healing the sick with magical and conventional means is the main task of the necromancers in the Amazon lowlands. Sometimes his influence surpasses that of the chief , as long as he is not - as with the Guaraní , for example - also in the leadership role. Sometimes its influence extends beyond death. In Guyana , for example, his soul becomes a helping spirit.

Spiritual experts have always played an important role among the Asháninka , Awetí ( Paié ), Yanomami ( Shaboliwa ), Kulina , Siona- Secoya , Shipibo-Conibo and Machiguenga , Bakairi peoples (the respective names for the experts in brackets ).

The tapirapé medicine men of Brazil go on a journey into the hereafter in their dreams. Women can only have children here if the shaman lets a ghost child come down to them. In healing the sick they use large quantities of tobacco, the smoke of which they swallow in the stomach, only to fall into a half-trance and vomit violently.

The shamanic ceremonies of the Awetí Indians belonging to the Tupí family on the lower Xingú are well described , discovered by the Austrian missionary Anton Lukesch in 1970 and described with their customs that were still unaffected by Christianity and Western modernity. The most important ritual complex here are the chants called Mbaraká , with which the supernatural powers are invoked. The magician sits on a stool in front of the ỳwára altar (two bars that are viewed as a ladder to the otherworld). In front of this altar he then dances into a trance with the help of an assistant and a rattle.

The traditional shamans of the Andean countries ( not referring to the Inca culture followers, who in the narrow sense have no necromancers) now pass on their knowledge to interested people in well-attended seminars, at indigenous celebrations or in individual sessions. In contrast to other continents, even the rituals arranged for tourists essentially correspond to the traditions.

The Uwishín shamans occupy a high position in the social hierarchy of the Shuar of the Andes Eastern slope in Ecuador and Peru . They buy their guardian spirits (Tsentsak) from each other and thus their position of power. These spirit servants are mostly in animal form. There are “good” and “bad” Uwishín similar to the white and black shamans of some Central Asian peoples. Accordingly, there is a belief that a sorcerer can send his servants to bewitch or to heal someone. Ayahuasca and concentrated tobacco juice are used as trance agents.

The Shamans of the Mapuche , a people in southern Chile who resisted colonization for a very long time in the Arauco War and who have a complex mythology, were and are women. During the initiation the shaman was sworn to her function on the top step of a wooden ladder, where she beat the drum (cultrún) . The ladder (Rehué) symbolizes the stairway to heaven. Both the shaman's drum, unique in South America, and the practices of the specialists (including soul guidance, healing, ecstatic flight, etc.) are reminiscent of the shamanism of Siberia.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Africa is considered the continent of medicine people, wizards, witches and obsession. The beliefs south of the Sahara mainly revolve around "magical power": an impersonal force from the shadowy world of gods and spirits that can "attack" everything: z. B. special stones or places, power-charged plants or animals, magicians, sorcerers and similar people, but also certain periods of time, words, numbers or even gestures. Power can have a negative or positive effect on people, and people in turn try to influence them in their own way through their behavior (observance of taboos and customs). Power is not always equally strong; it can concentrate: for example in amulets or in people who have mastered magic. Although the animistic ethnic religions of Africa are taking on more and more syncretistic forms due to the increasing influence of Islamic and Christian missionaries, they are still alive as a popular religion , especially among the rural population in many countries . Different types of medicine people and wizards play an important role almost everywhere.

Spiritual experts, however, do not only have a positive status, as in most other parts of the world, because in Africa misfortunes and strokes of fate are often attributed to evil sorcerers and wizards. They represent the dark side of magic. Such traits are considered innate, not acquired. There are numerous stories about such people, most of which deal with the terror that evil magic can wield. Wizards differ from witchers mainly in that they are stronger and can use evil magic in a targeted manner, for example through fetishes . Wizards and witches, on the other hand, are people who are assigned supernatural powers of which they are often unaware. This belief is very much alive in Africa to this day and extends to the upper echelons of economy, military and politics. Wizards and sorcerers are socially disregarded and must carry out their practices in secret; however, there are enough customers who use their services.

Apart from the few small hunting communities (such as San, Hadza, Damara or Pygmies) there are no religious and spiritual "all-round specialists" for all matters relating to the spirit world in African cultures ; and which, moreover, are recognized by the community as legitimized from the hereafter. This fact is also a major reason why Africa's necromancers appear in almost no shamanism concept. In the majority of the African populations south of the Sahara, there are instead a multitude of "experts" such as priests, clan and lineage elders, rainmakers, earth masters (who clear areas for clearing and reconcile the earth mother goddess through rites), fortune tellers, medicine people, magicians, Witches, prophets, etc., who derive their authority and their spiritual ability mostly from individual ghost experiences (obsession), age, descent or simply from their social position. For example, nature spirits are invoked by the chiefs of some ethnic groups. Before the colonial era, there was probably no chief whose office was not associated with religious functions. This line continues up to the rulers. Such sacred heads were subject to a number of rules of conduct and taboos, which in extreme cases culminated in the recognition of their ritual killing in the event of illness or at the end of their term of office. Such forms of rule no longer exist today.

The fortune tellers - or augurs - are often consulted when negative events cannot be explained. You have a thorough knowledge of the situation, a good gift of combination and the magic of an oracle to find a solution. Sometimes he takes on the further treatment or prosecution of the case. After the “diagnosis”, he often refers the person seeking help to a medicine man.

The medicine man works as a herbalist or naturopath who draws from an ancient traditional knowledge. The pharmaceutical effect of his medicine is probably not known to him, but he attributes it to magical effectiveness. In psychological and neurotic cases, which often show up in a certain type of obsession, an exorcistic ritual is used, which is associated with "powerful" music, dances and incense. In contrast to the Siberian shamans, an African medicine man does not suffer a loss of authority if the success fails. In this case, it is believed that negative forces were stronger than applied medicine. Similar to shamans on other continents, the medicine man does not exercise a secular office, but is considered the most important spiritual practitioner, because illness means a religious deficit for the African.

Most of the people mentioned so far do not work regularly on certain days or hours. Rather, they act according to how their help is needed and desired. This also applies to the office of priest, such as with the Ewe of West Africa. One becomes an Ewe priest either by inheritance or by calling a spirit. After teaching and consecration, he is installed in his office and then has his “assigned” magical power; At the same time, however, it also obliges him to behave in particular ways, such as sexual abstinence. He is responsible for cultic functions such as prayers and sacrifices, he sometimes performs exorcisms and also functions as a healer or fortune teller.

A special African figure is that of the seer . It is surrounded by an awe inspiring “charismatic aura” like that of a shaman; he feels gripped by a spirit power working through him. Seers are the only ones who can innovate in religious life, even if they contradict all rational considerations.

African specialists focus on death and illness. Hunting and weather spells are widespread, in the past there were also war spells, while magical field builders are rarer.

While Siberian or North American shamans, for example, usually have their “soul journeys” under conscious control, African ideas are exactly the opposite: The spirits control the person who is “possessed” by them as a more or less willless medium in the first place . This obsession can be positive and used by medicine men, or negative as a result of being taken over by a hostile spirit which one then tries to drive away. In addition, the prevailing idea in Africa is that spiritual powers can spontaneously and involuntarily "take possession" not only of patients, but also of spiritual experts at any time.

In order to consciously “call ghosts” - that is, to fall into trance-like states of consciousness - dances are often used. Drugs are mostly not used for this in Africa.

Spiritual specialists can still be found almost everywhere in Sub-Saharan Africa, even if in many countries they are only scattered or hidden next to the respective state religion. The old traditions and religions are still represented in the majority of the population in the following areas:

- West Africa: Ghana, Togo, Benin and Central Nigeria

- Central Africa: Southeast Cameroon, Central African Republic, South Sudan

- East Africa: East Uganda, West Kenya, North Tanzania

- South Africa: Northeast Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Madagascar

In the mostly very small hunter-gatherer groups in Northern Tanzania - the Hadza , Aasáx, Omotik-Dorobo and Akie-Dorobo - religion and rituals are minimalist. There are therefore no priests, shamans or medicine men. Many of the pygmy peoples who live in the wild are also not familiar with a personally defined medicine man.

In contrast to this, the Damara (magicians: Gama-oab ) and above all the Khoisan peoples (medicine man: e.g. Cho k'ao among the Tsoa) have highly respected spiritual healers, whose practices and diverse tasks are closest to the "real" “Remember shamans of Asia.

Australia

Although Aboriginal cultures are very similar everywhere, specialized necromancers did not appear in all groups. In addition, they did not have the highly institutionalized status as in Asia. They were mainly represented in Central Australia. Nevertheless, the old Australians have a highly complex mythical-religious world, so that Claude Lévi-Strauss deeply impressed the Aborigines called "aristocrats of the spirit among the hunter-gatherer societies".

While the exclusively nomadic way of life as hunter-gatherer among all Aborigines ended at the latest in the course of the 20th century, the myths about the dream time - the all-encompassing, timeless basis of society, custom and culture - and various religious rituals remained alive despite intensive Christianization in many places. Since the 1970s there has been a retraditionalization of some ethnic groups on the so-called outstations ( in some cases a return to the hunted way of life), which also gives importance to the shamans called “clever men” by the white population. Due to the diversity of languages in Australia, the names vary considerably: Examples are mabarn (Kimberley), karadji (western New South Wales), wingirii (Queensland) or kuldukke (south of the Murray River, Victoria)

Clever Men are documented in the current context in a few local groups from the following tribes: Yolngu , Kimberly People , Arrernte , Warlpiri , Pintupi , Martu and Pitjantjatjara

In some tribes, the “Clever Men” are ecstatic with the help of the herbal drug Duboisia hopwoodii - a tobacco-like nightshade plant that causes passionate dreams and traditionally chewed, but is now replaced by tobacco - as well as with dances and music and then - often very painful by pressing crystals under the fingernails and into the tongue - initiated .

“Clever Women” are far less common. The "normal" female doctors do not have the same power as the men. They are responsible for root and herbal medicine for minor injuries and minor illnesses, obstetrics, prophecies and love magic. Often there are family relationships or a marriage relationship with a Clever man, who is supported in this way by a woman who knows herbal. The Australian medicine men are usually assigned three main roles: he is the central keeper of social order, healer and ritual expert. Diseases of individuals and social disharmonies are closely related to the Aborigines, so that healing always has a social meaning. As with African wizards, the magical power is also used in Australia to threaten and exercise power. In addition, the experts have extensive knowledge of kinship, totem and clan relationships. Often the Clever Men interpret the dreams of the people, which are considered as a channel to the dream time. You do not practice with magical means, but always with direct help from the spirit world. They use maban or mabain - mostly quartz and other materials, feathers, blood, smoke, etc. - to transfer spiritual forces.

In addition to healing the sick, weather magic and other ceremonies, they are also responsible for maintaining and observing the tribal laws from the dream time and for the knowledge that has been handed down. The various functions are often personalized separately, for example as a healer or magician.

Oceania

With regard to the integration into the various concepts of shamanism, the same applies to Oceania as to Africa: Either the functions of the spiritual specialists deviate too much from the generalized models or the tasks are performed by completely different experts, so that very few authors include Oceania to have.

Melanesia and Micronesia

In Melanesia, organized priesthood or shamanism is mostly unusual; rather, each individual can exercise such functions if he or she has enough mana (divine power that can be acquired through actions). However, there are secret cult societies such as the Duk-Duk and Iniet secret societies in New Britain. Masking - face masks and mask dresses made from plant fibers - plays a major role. The secret societies are important for the transmission of sacred knowledge, for increasing one's own prestige and for carrying out initiation ceremonies. But the regulatory function that they assume within the traditional Melanesian societies, which are mostly organized without central bodies, should not be neglected. Admission to such secret societies is only possible after difficult exams.