Home states

The house states were an association of city-states between Bornu in the east and Niger in the west. They persist in what is now northern Nigeria and central Niger as recognized traditional states.

Founding history

Origin legend

The house states lay outside the great trans-Saharan trade route and therefore came into the focus of Arab geographers only late. However, its oral tradition is all the more pronounced. The Bayajidda legend handed down in the city-state of Daura , the traditional center of Hausaland, is of great importance . According to her, the inhabitants of Daura had immigrated from the north from Canaan and Palestine via the Sahara. Later, the actual founding hero Bayajidda, a king's son who is said to have fled Baghdad with his troops, came to Daura via Bornu . He reached the city by night alone on his horse. Here he killed the dangerous serpent of the well that ruled the city. The queen of the city married him in gratitude for his heroism. He fathered his son Karbagari with a concubine given to him by the queen. Then he fathered Bawo himself with the queen. Karbagari became the progenitor of the "seven void / banza states" and Bawo, together with the older son Biram, became the progenitor of the "seven house states". Even today, the inhabitants of the "seven Hausa" consider themselves the actual Hausa. Of the "seven Banza" two, Kebbi and Zamfara , belong to the states in which Hausa is spoken, but they are considered secondary.

Establishment of the house states

In a modified form, the Hausa legend corresponds to the biblical Abraham story with historical additions: the migration story of the queen points to an emigration of Assyrian deportees and the Bayajidda episode to the flight of the last Assyrian king from Nineveh at the end of the 7th century BC . Since Hausa belongs to the Chadian languages, there is also a connection with the spread of this branch of Afro-Asian. The medieval founding of the house states, which is mostly assumed today, can be explained by the remote position of these states in relation to the trans-Saharan trade and the resulting neglect by the Arab geographers.

In addition to the Bayajidda legend, the various original traditions of the individual Hausa states - in particular those of Gobir, Katsina, Kano, Kebbi and Zamfara - indicate that all original Hausa dynasties can be traced back independently of one another to emigrants from the Near East. In Central Sudan, the migrants encountered representatives of segmented societies who can be regarded as Niger-Congo speakers in terms of language and who have either been expelled or integrated into the new states in the form of Azna .

The seven Hausa and the seven Banza states

The "seven house states " ( Hausa bakwai ) include Biram , Daura, Kano , Zaria , Gobir , Katsina and Rano . The "seven Banza states" ( Banza bakwai ) include the two states Kebbi and Zamfara , in which Hausa is spoken, and five other states in the south whose names are not the same in all versions of the Bayajidda legend. Usually the following five states are mentioned: Gurma , Borgu , Yawri , Nupe and Kwararrafa / Jukun . Sometimes Gwari is also called and Gurma is omitted. The division of these states has been explained since Heinrich Barth using the predominant local language. Why, however, Kebbi and Zamfara, in which Hausa was spoken, were not counted among the Hausa states, remained a mystery. According to a more recent theory by the Bayreuth historian Dierk Lange, the traditions of the seven actual home states are shaped by Israelite immigrants and those of the seven Banza states by Mesopotamian immigrants.

Medieval history of the house states

Marginality of the house states

Despite their linguistic and cultural unity, the house states never formed a common empire. Al-Yaqubi first mentioned it in the 9th century AD between Kanem and Malal . The great traveler Ibn Battuta , who was on his way back from Mali to Morocco north of Hausaland in Takedda in 1354 , heard about Gobir, Zaghay / Katsina and Bornu . With the exception of Gobir , Zamfara and Kebbi , these were city-states whose prosperity was based on flourishing trade and industry. Kano and Katsina in particular, but also Zaria , were distinguished by their numerous residents and lively craft activities. The focus was on regional trade with neighboring countries and not on trans-Saharan trade . In addition, the house states were subject to the rule of powerful neighboring empires for longer periods of time: Kanem-Bornu in the east and Mali in the west, and Songhay in the early 16th century. Therefore the Arab geographers hardly noticed the smaller states of central Sudan.

Supreme rule of Kanem-Bornu

Despite the earlier arrival of Magajiyas , Bayajidda is considered the actual founding hero of Daura and the house states due to his snake killing. One regards his earlier stay in Bornu - actually Kanem-Bornu or even Kanem - as the legendary justification for a vassalage to the Chad state that lasted until the beginning of the 19th century. The tribute payments "of the countries of the west" mentioned by the Kano Chronicle only after the rule of Abdullahi Burja (1438-1452) correspond to a resumption of old tribute payments, the interruption of which is a consequence of the weak period of the Chad state following the abandonment of Kanems from 1381 to 1449 was. The slave tributes of the house states were first delivered to Daura and from there delivered to the ruler Kanem-Bornus once a year. At least some of the Banza states also paid tributes to the Chad state.

Islamization of the house states

The late Islamization of the house states compared to Kanem-Bornu , Gao and Ghana can be explained by the remote location of the country in relation to the most important routes of the Trans-Saharan trade , the strong expression of the sacred kingship and the powerful party of the Azna clan. According to the Kano Chronicle , Wangara traders from Mali spread Islam in Kano at the time of King Yaji (1349–1385). Due to the stronger resistance of the Azna, Islam was only introduced in Katsina a hundred years later. Under the leadership of Muhammad Korau (1445–1495) it was possible here to overcome and marginalize the Azna under the Durbi ruler. The Durbi had to give up supreme power, but his high official status and his rule over the Azna remained with him. In other house states, Islam was in some cases only introduced in the 18th century.

History of the house states since the Fulani jihad

The Fulani jihad and its consequences

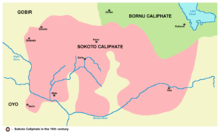

In all house states, Islam met with strong resistance from partisans of the sacred kingship. The officials, whose sound gods belonged to the party of the Azna gods, were particularly indomitable. The Fulani scholar Usman dan Fodio (1744-1817), who was temporarily active at the royal court of Gobir, denounced the "mixing" of Islam and paganism. In 1804 he declared jihad to the house kings . With the help of their Fulani tribesmen, of whom only a thin upper class was firmly rooted in Islam, some Hausa allies and contingents of the Tuareg, his commanders attacked the individual Hausa states and Bornu . They succeeded in driving all the Hausa kings out of their capitals and in replacing them with Fulani leaders. In his home area on the outskirts of Gobir, Usman dan Fodio founded the new capital Sokoto , which gave the Sokoto Caliphate its name. Members of the royal houses of Zaria , Katsina , Gobir and Daura were able to flee and establish secondary rule beyond the reach of the Fulani. In Bornu, the Fulani were initially also successful, until they ultimately failed due to al-Kanemi's resistance . Within the Sokoto Caliphate there was a permanent division of the empire in 1808 with the establishment of Abdullahi dan Fodio (1808-1828), the brother of Usman dan Fodios, as Emir of Gwandu . In 1849 a descendant of the Lekawa von Kebbi rose against the rule of the Sokoto caliphate and established an independent Kebbi empire between Sokoto and Gwandu, which also continues to this day.

Changes in the colonial era

The British conquered the Sokoto Empire in 1903 and incorporated it into the Nigerian Protectorate. They stabilized the new balance of power created by the Fulani jihad. Only in Daura did they relieve the Fulani king of power and put in his place in 1906 the house king Malam Musa (1904–1911) as ruler of a reunited kingdom of Daura. As part of the general modernization process, the kings of the Hausa were largely marginalized compared to the modern administration. As traditional country fathers, their rulers continued to enjoy great respect among the population. Not much has changed in this regard even after Nigeria's and Niger's independence in 1960. To this day you can find the old house states as emirates within the federal states of Northern Nigeria and as chefs de canton within the départements of the Republic of Niger . The border between the two modern states largely follows the border of the Sokoto Caliphate, so that north of the border mostly less strict Muslims can be found than south of it.

Trade and commerce

In the pre-colonial period, the house towns were widely known for their numerous handicraft products: woven fabrics and clothing, tanned leather and leather goods, weapons and other iron products. These goods, as well as slaves , were partly exported to North Africa. Horses, weapons, fabrics and clothing and other manufactured goods were imported from the north. The salt from the salt pans of the Sahara was also important . There was also a brisk trade in cola nuts from the Ashanti Empire . In addition to the Wangara, today's Diula from the Mande region , the Hausa were the most famous traders in West Africa. The Islam promoted at the same time their cohesion and mobility. Away from home, they mostly settled in their own suburbs on the outskirts of foreign cities.

See also

literature

- Adamu, Mahdi: The Hausa Factor in West African History , Zaria 1978.

- Barth, Heireich: Travels and discoveries in North and Central Africa , 5 vols., Gotha 1857-8.

- Hogben, SJ, and Anthony Kirk-Greene: The Emirates of Northern Nigeria , London 1966.

- Johnston, HAS: The Fulani Empire of Sokoto , London 1967.

- Lange, Dierk: Ancient Kingdoms of West Africa , Dettelbach 2004 (chapter XII: "Hausa history in the context of the Ancient Near Eastern World", pp. 215-306).

- - "The Bayajidda legend and Hausa history" (PDF; 748 kB), in: E. Bruder and T. Parfitt (eds.), Studies in Black Judaism , Cambridge 2012, 138–174.

- Last, Murray: The Sokoto Califate , London 1967.

- Nehemia Levtzion and John Hopkins: Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History , Cambridge 1981.

Web links

- Bayajidda legend (palace version) (PDF; 738 kB) in Lange, Ancient Kingdoms , Dettelbach 2004, 289–296.

- Lange, Dierk: "An Assyrian successor state in West Africa: The ancestral kings of Kebbi as ancient Near Eastern rulers" , Anthropos, 104, 2 (2009), 359-382.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Palmer, Memoirs , III, 132-3; Smith, Daura , 52-55; Lange, "Bayajidda legend", (PDF; 738 kB) in Lange, Ancient Kingdoms , 289-295.

- ^ Long "Bayajidda legend" (PDF; 748 kB), 150-4.

- ↑ Hogben / Kirk-Greene, Emirates , 160, 184; Adamu, "Hausa Factor", 269-275.

- ^ Long "Bayajidda legend" (PDF; 748 kB), 154-7.

- ^ Barth, Reisen , II, 81-82.

- ↑ Lange "Bayajidda legend" (PDF; 748 kB), 157-164.

- ^ Levtzion / Hopkins, Corpus , 21, 302.

- ^ Hogben / Kirk-Greene, Emirates , 82-88.