Kanem Bornu

Kanem-Bornu is a former empire whose center has been east of Lake Chad since the pre-Christian era, where Arab geographers have located Kanem since the 9th century. The founding history of Kanem-Bornus is therefore identical to that of Kanem .

Kanem and Kanem-Bornu

From the earliest times the rule of the kings of Kanem extended over Bornu. According to the founding legend of the Hausa , the snake killer Bayajidda came from Bornu (actually Kanem) to Daura . He founded the first Hausa state in the west of the Chad state, which from then on was dependent on the powerful state in the east. West of Lake Chad is also Zilum , an archaeological site that shows the existence of proto-urban structures since the middle of the 1st millennium BC. Chr., Attested. In Bornu, the Sefuwa also encountered the Sao urban culture for the first time , which still survives in legends today. One sees in them mostly the Chadian indigenous population of the western province of the empire of the Sefuwa. However, there is much evidence that it was actually a subgroup of the early founders of the Chad Empire.

From the much later reports of al-Yaqubi in the 9th century AD about the Lake Chad area, a geographical proximity between the empire Kanem and the house states emerges. Lake Chad itself was not mentioned until the 13th century by Ibn Said . Therefore, it is only since then that one can clearly distinguish geographically between Kanem east and Bornu west of Lake Chad. During this time, the Sefuwa had ruled the Chad Empire for 150 years, which stretched east and west of Lake Chad. The previous rule of the Duguwa therefore affected the history of Kanem more than that of Kanem-Bornu.

The Kanem-Bornu Empire

The double kingship of Kanem-Bornu

Since the beginning of the 13th century at the latest, the rulers resided alternately in Kanem and Bornu. Ibn Said mentions the extension of the Chad empire to Jaja immediately west of Lake Chad and Takedda far in the north-west. Ibn Chaldun tells of the gift of a giraffe to the Sultan of the Hafsids in 1257 by "the King of Kanem and ruler of Bornu". The Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi becomes even clearer . He writes in relation to Ibrahim II. (1290-1310) of a "throne of Kanem and a throne of Bornu". Apparently Bornu was so integral to the Chad empire in the 13th century that the province east and west of Lake Chad were regarded as equivalent official seats of the Sefuwa. Ibn Battuta heard in 1353 in Takedda, far to the north, of a ruler named Idris (ibn Ibrahim) (1335-1359), whom he called "King of Bornu". The divan is therefore not easy to follow if it dates the relocation of the Sefuwa ancestral seat from Kanem to Bornu to the second half of the 14th century.

Expansion of Kanem-Bornus in the 13th century

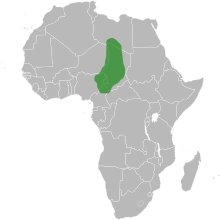

The extent of the Chad Empire in the older periods is extremely uncertain. Thanks to Ibn Said's extensive reports, the boundaries can only be determined more or less precisely for the reign of Dunama Dibalemi. From east to west, Kanem-Bornu extended from Darfur to beyond the territory of the house states . In the north it reached the oasis group of the Waddan , 200 km from the Mediterranean coast, in the south mainly the Kotoko were integrated into the empire early on. Here the border remained almost unchanged until the beginning of the colonial era. Islam also made little progress in the south for centuries, as the peoples of these areas were regularly haunted by slave raids from Kanem-Bornu. There were, however, exceptions with regard to the small states on the southern periphery of Kanem-Bornus: Fika , Mandara and Bagirmi were spared as long as they regularly delivered the slave tributes imposed on them. Kanem-Bornu in its greatest extent was therefore not an empire in the actual sense, but a union of states. Trade and industry flourished here as long as the Sefuwa guaranteed general security.

Destruction of the national shrine "Mune" by Dunama Dibalemi

The Muslim traders of North Africa saw in Dunama Dibalemi (1203–1242) a praiseworthy reformer who decisively advanced the process of Islamization. The internal sources, which denounce the exaggerated zeal for reform of the king, are different. The reason for their criticism was the destruction of the great national shrine called Mune . Ibn Furtu reports two centuries later of a seven-year civil war between the central power and the Tubu that this triggered . Dunama II emerged victorious from the fighting, but the indignation about the lack of respect for national tradition formed a dangerous explosive in society. Even during Dunama's lifetime, some of his sons took over the leadership of opposing parties, among which the Duguwa in particular can be assumed. One of these parties that refused to accept giving up its own tradition in favor of Islam was the Bulala .

Revolt of the Bulala, retreat of the Sefuwa to Bornu (1381)

The overwhelming power of the ruling Sefuwa forced the main opposition party, the Bulala , to withdraw temporarily to the area of Lake Fitri south of Kanem. Reinforcing the Arabs who immigrated from the Nile Valley area and taking advantage of dynastic conflicts among the Sefuwa since the rule of Dawud b. Ibrahim (1359-1369), they attacked the Sefuwa. From 1369 to 1375, four successive kings of the Sefuwa fell fighting the Bulala. The twentieth king of the Sefuwa, Umar b. Idris (1376-1381) finally decided to give up Njimi, the old capital in Kanem. He withdrew with his royal court to Kaga in Bornu. This retreat is by no means to be understood as an exodus to a largely unknown country. Rather, it was about the tactically necessary relocation of the seat of rule of the Sefuwa from the ancestral seat of Kanem in the east to the second province of Bornu in the west, which had become unsafe due to the immigration of the Arabs from the Nile valley and the attacks of the Bulala. From here the Sefuwa and before them the Duguwa ruled over the house states for centuries. In this respect, the event was by no means as catastrophic as the divan represents. Even after the abandonment of Kanem, the Chad state remained the undisputed leading power of Central Sudan under the Sefuwa.

Written language

The written language used was Arabic, but also Old Kanembu .

The Bornure Empire

Consolidation of the Sefuwa rule in Bornu (1455–1800)

To the west of Lake Chad, the dynastic conflicts continued despite the attacks by the Bulala.

Only when the new capital Birni Gazargamo was founded by Ali Ibn Dunama (Ali Gaji, 1455–1487) did the situation finally stabilize. Under Idris Alaoma (1564–1596), who had acquired firearms from the Ottomans in North Africa, the Sefuwa Kanem succeeded in regaining their possession. Thanks to the Dalatoa governor dynasty they established, they exercised supremacy here until they were overthrown in 1846. Other dependent peoples also had to pay tributes. Inside, the long-term security created a high degree of prosperity. In the 18th century, however, signs of decay made themselves felt.

Rule of the al-Kanemi (1814-1893)

After Bornu almost succumbed to the onslaught of Usman dan Fodio between 1808 and 1809, the devout Muhammad al-Amîn al-Kânemî was able to wrest large parts of the empire from the Fulbe again; his descendants ruled until 1893 and again under British colonial rule.

Rule of Rabeh and the beginning of the colonial era (1893–1900)

In 1893 the Sudanese Arab slave hunter Rabeh az-Zubayr (1845–1900) conquered Bornu after he had previously brought Bagirmi under his control. He came into conflict with the colonial interests of France. On April 22, 1900 Rabeh lost his life and empire in the battle of Kousséri on Lake Chad against French colonial troops under Colonel François Joseph Amédée Lamy (* 1858; † April 22, 1900). As a result, the area that produced the 1,000-year-old Saif dynasty was divided among the colonial powers France , Great Britain and Germany .

literature

- Barkindo, Bawuro: "The early states of the Central Sudan", in : J. Ajayi and M. Crowder (eds.), The History of West Africa , vol. I, 3rd ed. Harlow 1985, 225-254.

- Barth, Heinrich: "Chronological table, containing a list of the Sefuwa", in: Travel and Discoveries in North and Central Africa , Vol. II, New York, 1858, 581-602.

- Brenner, Louis, The Sehus of Kukawa , Oxford 1973.

- Breunig, Peter, "Groundwork of human occupation in the Chad Basin, 2000 BC-1000 AD", in: A. Ogundiran (ed.), Precolonial Nigeria , Trenton, NJ, 2005, 105-131.

- Cohen, Ronald: The Kanuri of Bornu , New York 1967.

- Connah, Graham: Three Thousand Years in Africa , London 1981.

- Conte, Edouard: Marriage Patterns, Political Change and the Perpetuation of Social Inequality in South Kanem (Chad) , Paris 1983.

- Desanges, Jehan: Recherches sur l'activité des Méditerranéens aux confins de l'Afrique , Rome 1978.

- Gronenborn, Detlef: Kanem-Borno - A brief summary of the history and archeology of an empire in the Central 'bilad el-sudan. In: Chr. DeCorse (Ed.): West Africa During the Atlantic Slave Trade: Archaeological Perspectives , London / Washington, 101–130.

- Gronenborn, Detlef and Carlos Magnavita: Imperial expansion, ethnic change, and ceramic traditions in the Southern Chad Basin. A terminal nineteenth century pottery assemblage from Dikwa, Borno State, Nigeria. International Journal of Historical Archeology 4/1, 2000, 35-70.

- Hallam, W., The Life and Times of Rabih Fadl Allah , Devon 1977.

- Ibn Furṭū: "The Kanem wars", in: Herbert R. Palmer: Sudanese Memoirs , Vol. I, Lagos 1928, pp. 15–81.

- -: "The Bornu wars", in: Lange, Sudanic Chronicle , pp. 34-106.

- Lange, Dierk: Le Dīwān des sultans du Kanem-Bornu , Wiesbaden 1977.

- -: "The kingdoms and peoples of Chad" (PDF; 1.4 MB), in: DT Niane (ed.), General History of Africa , vol. IV, UNESCO, London 1984, 238-265.

- -: A Sudanic Chronicle: the Borno Expeditions of Idrīs Alauma , Wiesbaden 1987.

- -: "The Mune-symbol as the Ark of the Covenant between duguwa and Sefuwa" (PDF; 509 kB), Borno Museum Society Newsletter , 66-67 (2006), 15-25.

- -: "Immigration of the Chadic-speaking Sao towards 600 BCE" (PDF; 7.3 MB) Borno Museum Society Newsletter , 72–75 (2008), 84–106.

- -: "An introduction to the history of Kanem-Borno: The prologue of the Diwan" (PDF; 308 kB), Borno Museum Society Newsletter 76–84 (2010), 79–103.

- -: The Founding of Kanem by Assyrian Refugees approx. 600 BCE: Documentary, Linguistic, and Archaeological Evidence (PDF; 1.6 MB), Boston, Working Papers in African Studies N ° 265.

- Le Rouvreur, Albert: Saheliens et Sahariens du Tchad , Paris 1962 (new edition, Paris 1989).

- Levtzion, Nehemia, and John Hopkins: Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History , Cambridge 1981.

- Magnavita, Carlos: "Zilum - Towards the emergence of socio-political complexity in the Lake Chad region", in: M. Krings and E. Platte (eds.), Living With the Lake Cologne 2004, pp. 73-100.

- Magnavita, Carlos, Peter Breunig, James Ameje and Martin Posselt: "Zilum: a mid-first millennium BC fortified settlement near Lake Chad". Journal of African Archeology 4, 1 (2006) , pp. 153-169.

- Levtzion, Nehemia and John Hopkins: Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History , Cambridge 1981.

- Platte, Editha: Women in Office and Dignities: Scope of Action for Muslim Women in Northeast Nigeria , Brandes and Apsel, Frankfurt a. M. 2000.

- Smith, Abdullahi: The early states of the Central Sudan , in: J. Ajayi and M. Crowder (eds.), History of West Africa , Vol. I, 1st ed., London, 1971, 158-183.

- Urvoy, Yves: L'empire du Bornou , Paris 1949.

- Zeltner, Jean-Claude: Pages d'histoire du Kanem, pays tchadien , Paris 1980.

Web links

- Dierk Lange: "Kanem-Bornu" website with published full texts.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Magnavita, "Zilum", 83-94.

- ↑ Lange, "Immigration of the Sao" (PDF; 7.3 MB), 95-104.

- ↑ Levtzion / Hopkins, Corpus , 354; to be supplemented by D. Lange, "Maqrizi", Annales Islamologiques , 15 (1979), 207.

- ^ Levtzion / Hopkins, Corpus , 302.

- ↑ Lange, Diwan , 76-77.

- ↑ Lange, "Mune-symbol" (PDF; 509 kB), 15-25.

- ^ The secret of the Sultanate of Zinder , in: Süddeutsche Zeitung , September 21, 2019

- ↑ Brenner, Shehus , 9-130.

- ↑ Hallam, Life , 321-6.