Giraffes

| Giraffes | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Maasai giraffe with young animal in the Zambian savanna |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Giraffa | ||||||||||||

| Brisson , 1762 |

The giraffes ( Giraffa ), pronunciation [ ɡiˈrafə ] or [ ʒiˈrafə ], are a genus of mammals from the order of the artifacts . Originally only one species was assigned to it with Giraffa camelopardalis and the trivial name "Giraffe". However, molecular genetic studies from 2016 show that the genus includes at least four species with seven separate populations . The giraffes are the tallest land animals in the world. To distinguish them from the related okapi (so-called "forest giraffe"), they are also referred to as steppe giraffes.

features

anatomy

Males (bulls) are up to 6 meters high and weigh an average of around 1,600 kilograms. Females (cows) grow up to 4.5 meters high and weigh around 830 kilograms with a shoulder height between 2 and 3.5 meters.

The neck of the giraffe is exceptionally long. As with almost all mammals, the cervical spine consists of only seven cervical vertebrae , which are, however, greatly elongated. The neck is held at an angle of about 55 degrees by a single, very strong tendon . The tendon runs from the back of the giraffe's head to the rump and is responsible for the "hump" between the neck and the body. Resting keeps the neck and head in the upright position; to move the head down, e.g. B. to drink, the giraffe has to work hard. The tongue can be 50 centimeters long. It is able to grip and is heavily pigmented in the front area to protect against sunburn.

The pattern of the coat consists of dark spots that stand out against the lighter basic color. The shape and color of the spots vary depending on the species. The underside of the animals is light and unspotted. The spots are used to camouflage and regulate body temperature. In the subcutaneous tissue, a ring-shaped artery runs around each spot , sending branches out into the spot. The giraffe can give off more body heat through increased blood flow and is not dependent on shade. In male giraffes in particular, the spots get darker with age. However, this does not happen in all individuals to the same extent or with the same intensity, so that lighter and darker animals appear in the same age group. According to studies on animals from the Etosha National Park , darker old bulls are often solitary and are characterized by a dominant appearance compared to other members of the sexes during reproduction. Lighter individuals of the same age, on the other hand, often lead a life in association and are less dominant, which leads to less success in mating with cows. Accordingly, the coat color reflects the social status of an individual.

The smell of the coat is unpleasant for humans. Bull giraffes smell stronger than cows. At feces remember specifically the substances indole and skatole , moreover, find octane , benzaldehyde , heptanal , octanal , nonanal , p -cresol , tetradecane and hexadecanoic in fur. Most of these compounds inhibit the growth of bacteria or fungi such as those found on mammalian skin. The content of p -cresol in giraffe hair is sufficient to deter ticks.

Two cone-like horns sit on the head of both sexes. In rare cases, another pair of horns grow behind it. Some giraffes also have a bony hump between the eyes, which is structured similar to the horns.

Giraffes reach a top speed of 55 km / h. The long legs can only carry the giraffe on firm ground. The animals therefore avoid swampy areas.

Giraffes communicate in the infrasound range, which is inaudible to humans, with frequencies below 20 Hertz .

Cardiovascular system

Because of the length of the upright neck, the force of gravity in the blood vessels at heart level leads to an unusually high pressure that must be counteracted. The heart of the giraffes must therefore be particularly powerful in order to generate the necessary blood pressure. It weighs on average about 0.51% of body weight, similar to other mammals.

The blood pressure , measured on arteries close to the heart, is 280 to 180 mm Hg (compared to humans: 120 to 80) and is therefore the highest of all mammals. This means that it is sufficient to achieve a mean arterial pressure of 75 mm Hg even in the head two meters higher (humans: 60 mm Hg). Due to the force of gravity and the resulting pressure of the water column in the leg vessels, there is a pressure of 400 mm Hg in the arteries of the feet (humans: 200 mm Hg). The leg arteries are particularly thick-walled in order to prevent fluid from escaping into the legs and the development of edema . The skin on the legs is also particularly tight, so that it acts like a compression stocking . To build up the high pressure, the heart rate at rest is 60 to 90 beats per minute (humans: 70), while galloping 175 beats per minute were measured. This is unusually high, as the heart rate in mammals generally decreases with increasing body weight and is therefore significantly lower in animals of comparable weight.

Large pressure differences arise in the head when the giraffe bends down, for example to drink: The arterial pressure then equals that in the feet. Fluid buildup around the brain could be life threatening. In order to avoid such accumulations, the giraffe has a network of elastic blood vessels close to the brain, which can absorb blood when the pressure rises and thus lead to relief. This avoids congestion in the veins. In addition, the major neck veins, called the jugular veins , have valves that are not found in other mammals to prevent reflux when the head is bowed. Contrary to some popular scientific reports, however, no valves could be detected in the cervical arteries.

distribution

Giraffes are common in African savannas . Today they only live south of the Sahara , especially in the grass steppes of East and South Africa. The populations north of the Sahara were eradicated early by humans: during early antiquity in the Nile Valley and around the 7th century in the coastal plains of Morocco and Algeria . In the 20th century, giraffes disappeared from many other areas of their range.

Way of life

Giraffes prefer to graze on acacias . The animals grab a twig with their tongue, which is up to 50 cm long, pull it into their mouth and pull off the leaves by pulling their heads back. The tongue and lips are made in such a way that they are not damaged despite the thorny branches. Due to the high bite force and the massive molars, the branches, leaves and twigs can be quickly ground into small pieces and slide down the neck, which is up to 2.5 meters long, within a very short time. Each day a giraffe consumes about 30 kg of food; this takes sixteen to twenty hours. The fluid requirement is largely met from food, so that giraffes can go for weeks without drinking. If they do drink, they have to spread their front legs wide so that they can lower their heads far enough to the water source; they do the same when they take up food from the ground, which they do only under very unfavorable circumstances.

Giraffes live solitary or in loose associations. The social behavior depends on gender: Females always form herds of 4 to 32 animals, which, however, keep changing in composition. Young or less dominant males form their own associations, so-called bachelor groups, dominant old bulls are mostly loners. The group size depends on the habitat and is not influenced by the presence of larger predators . It is noticeable that cows with offspring are more often found together in smaller groups. In the Namib in south-western Africa, mixed groups tend to form larger associations than single-sex groups, which means that gender composition is an important factor. In contrast, herds with young animals do not increase in size, which leads to the conclusion that the protection of the offspring against hunting is not controlled by the group size in giraffes. Another important factor in herd formation is the spatial availability of food. However, this does not affect the seasons, which means that herds can be viewed as relatively stable. Fluctuations in herd size are therefore dependent on the food supply and can fluctuate significantly over days. In the mornings and evenings, there are often larger gatherings that serve to eat food together.

If two bulls meet, a ritualized fight usually ensues in which the animals stand next to each other and hit their head against the neck of the competitor. During the mating season, such fights can turn out to be more aggressive and become fierce, in which one of the competitors is knocked unconscious.

Contrary to popular belief, giraffes eat from low bushes or halfway up, especially in the dry season. For this reason, it is now doubted that the giraffes have their long necks only because of food choices. One argument against the food intake theory is that giraffes have elongated their necks more than their legs in the course of evolution. However, longer legs would be energetically more beneficial if it were only about height gain. A current theory for the long neck therefore sees the struggle of male giraffes for dominance and females as a main reason. A long neck is advantageous in combat.

Giraffes sleep several times in a 24-hour day, lying on their stomachs with their legs drawn up and their heads back on their bodies. Sleep usually only lasts for a short time, in more than half of all observations less than 11 minutes, at most up to 100 minutes. The REM phase lasts an average of 3 minutes. It is assumed that the animals in the lying position are at the mercy of predators, as they can only get up slowly and defend themselves by kicking with their legs. They spend most of the night ruminating. During the day, giraffes occasionally doze while standing, which makes up less than 50 minutes of a 24-hour day. This gives an individual around 4.6 hours of sleep per day cycle. Young animals sleep longer on average.

offspring

The gestation period lasts 14 to 15 months. Usually only a single calf is born. The birth takes place standing, so that the newborns fall to the ground from a height of two meters. Newborn giraffes weigh around 50 kilograms and 1.8 meters high, so they just reach the mother's udder. While her legs are already well developed at this point, her neck grows to almost three times its length postnatally. You stand firmly on your feet within an hour and start walking after a few hours. However, the calves are only reunited with the herd after two to three weeks.

A calf stays with its mother for about a year and a half. It becomes sexually mature at the age of four and reaches full size at the age of six. Giraffes can live up to 35 years in captivity. The maximum age in the wild is estimated to be 22 for males and 28 for females, but too few studies have been carried out to date.

Adult giraffes defend themselves against predators with blows of their front hooves. However, due to their size and defensive ability, they are rarely attacked. Young animals, on the other hand, often fall victim to lions , leopards , hyenas and wild dogs . Despite the protection of the mother, only 25 to 50 percent of the young reach adulthood.

Systematics

The giraffes form a genus within the family of giraffes-like (Giraffidae) and the order of the cloven-hoofed animals (Artiodactyla). In addition, only the okapi ( okapia ) is counted as part of the family. Today the family is limited to the African continent, but in its ancestral past it was also spread over large parts of Eurasia. Due to their horn-like skull formation, the giraffe-like are counted to the group of forehead weapon bearers (Pecora). Within this they form the sister taxon of a group consisting of the deer (Cervidae), musk deer (Moschidae) and horned bearers (Bovidae). The separation from this group took place in the transition from the Oligocene to the Miocene about 25 million years ago.

For a long time the genus was considered to be monotypical and contained only one representative with the species Giraffa camelopardalis . Numerous subspecies were assigned to this, which, in addition to the area of distribution, were often differentiated based on the formation of the horns or the fur pattern. For example, the Nubian giraffe ( G. c. Camelopardalis ) has large, medium-brown spots that are irregularly square in shape and separated by relatively narrow white bands. The spots of the Masai giraffe ( G. c. Tippelskirchi ) are smaller and darker and almost star-shaped. The spots of the reticulated giraffe ( G. c. Reticulata ), which represent dark polygons between which very narrow white bands run, so that the impression of a network is created, are unique . However, there was no agreement on the exact number of subspecies. In 1904 Richard Lydekker listed a total of ten subspecies within Giraffa camelopardalis , which he divided into two large groups of forms: on the one hand, those with well-developed front horns and unspotted lower legs, on the other hand, those with missing front horns and spotted lower legs. However, Lydekker considered the reticulated giraffe ( Giraffa reticulata ) to be independent, but not without pointing out that it may only be a subspecies. More modern systematics usually differentiated between six and nine subspecies.

| subspecies | Lydekker 1904 | Dagg 1971 | Grubb 2005 | Skinner and Mitchell 2011 | Ciofolo and Le Pendu 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola Giraffe ( G. c. Angolensis ) | + | + | - | + | + |

| Kordofan giraffe ( G. c. Antiquorum ) | + | + | - | + | + |

| Nubian Giraffe ( G. c. Camelopardalis ) | + (as G. c. typica ) | + | + | + | + |

| "Congo Giraffe" ( G. c. Congoensis ) | + | - | - | - | - |

| "South Lado Giraffe" ( G. c. Cottoni ) | + | - | - | - | - |

| Cape giraffe ( G. c. Giraffa ) | + (as G. c. capensis ) | + | + | + | + |

| West African Giraffe or Nigerian Giraffe ( G. c. Peralta ) | + | + | - | + | + |

| Reticulated giraffe ( G. c. Reticulata ) | + (as a separate species) | + | + | + | + |

| Uganda giraffe or Rothschild giraffe ( G. c. Rothschildi ) | + | + | + | + | - |

| Thornicroft giraffe ( G. c. Thornicrofti ) | - | + | + | + | + |

| Maasai giraffe ( G. c. Tippelskirchi ) | + | + | + | + | + |

| "Transvaal Giraffe" ( G. c. Wardi ) | + | - | - | - | - |

Molecular genetic studies by a ten-person research group led by David M. Brown in 2007 on six known subspecies ( G. c. Angolensis , G. c. Giraffa , G. c. Peralta , G. c. Reticulata , G. c. Rothschildi and G . c. tippelskirchi ) confirmed their genetic distinguishability. In addition, the results showed that each of these subspecies formed a monophyletic group, none of which was in a (measurable) gene exchange with a neighboring group. The research group concluded that the respective subspecies could be raised to their own species status. A study by Alexandre Hassanin and colleagues published almost at the same time came to a similar result. In addition to the subspecies already examined, it also included the Kordofan giraffe ( G. c. Antiquorum ). Hassanin and research colleagues divided the subspecies into a northern group ( G. c. Antiquorum , G. c. Peralta , G. c. Reticulata , G. c. Rothschildi ) and a southern group ( G. c. Angolensis , G. c. Giraffa , G. c. Tippelskirchi ), each of which had its own character. In addition, according to the published report, there were closer ties between the West and East African giraffes in the northern group than with the Central African. Citing the results of the groups of scientists around Brown and Hassanin and using their own morphological analyzes, Colin Peter Groves and Peter Grubb raised eight subspecies to the species status in a revision of the ungulates, including the seven genetically investigated forms (whereby they were the Uganda or Rothschild giraffe as identical to the Nubian giraffe) and additionally the Thornicroft giraffe. Further studies later showed that the Thornicroft giraffe, although genetically distinguishable, is embedded within the range of variation of the Maasai giraffe and must therefore be regarded as identical to it.

A DNA study presented in 2016 by a research team led by Julian Fennessy and Axel Janke based on 190 individuals from a total of nine recognized subspecies, including for the first time those of the Nubian giraffe ( G. c. Camelopardalis ), represents the most extensive genetic analysis to date four monophyletic groups were identified, which the researchers believe should be recognized as separate species. These four monophyletic groups are divided into seven distinguishable populations . Similar to the Thornicroft giraffe before, the Uganda giraffe turned out to be a regional representative of the Nubian giraffe in this case. Accordingly, the genus of giraffes can be broken down into the following species and subspecies:

|

Internal systematics of the giraffes according to Fennessy et al. 2016

|

- Northern giraffe ( Giraffa camelopardalis ( Linnaeus , 1758))

- Kordofan giraffe ( Giraffa camelopardalis antiquorum Jardine , 1835)

- Nubian giraffe ( Giraffa camelopardalis camelopardalis ( Linnaeus , 1758))

- West African giraffe ( Giraffa camelopardalis peralta Thomas , 1898)

- Southern giraffe ( Giraffa giraffa von Schreber , 1784)

- Angola giraffe ( Giraffa giraffa angolensis Lydekker , 1903)

- Cape giraffe ( Giraffa giraffa giraffa by Schreber , 1784)

- Reticulated giraffe ( Giraffa reticulata de Winton , 1899)

- Maasai giraffe ( Giraffa tippelskirchi Matschie , 1898)

In addition to these, there were one or more subspecies in North Africa that were already extinct in ancient times . Since monochrome giraffes can often be seen in Egyptian depictions, it has sometimes been speculated whether the subspecies there was unspotted. However, there are also depictions of spotted giraffes. Even within a subspecies a pattern of spots occurs occasionally, which is completely untypical for the region, so that the origin cannot always be determined with certainty from the drawing.

Man and giraffe

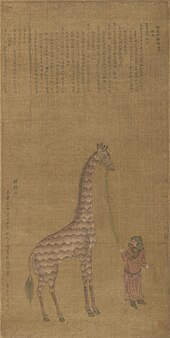

As early as the Bubalus period between 10,000 and 6,000 BC. The giraffe and other large game were depicted on rock carvings in today's Sahara with amazing attention to detail.

In ancient Egypt , giraffes were considered oracles with shamanic features. According to Egyptian popular belief, giraffes warned humans and animals of dangerous predators and storms. This belief goes back to the ability of the giraffe to recognize conspecifics and predators at an early stage because of its size and sharp eyes. The Egyptian word that was used to depict giraffes is ser (u) and means “to spy”, “to look into the distance”, but also (symbolically) to “predict”. Giraffes were already rare in Egypt in the Predynastic Epoch (4000–3032 BC), which is why they were preferably caught alive and brought to the court of the Pharaoh . Even in later dynasties, depictions of giraffes are rather sparsely documented, which underlines the rarity of the animals. Live giraffes apparently had to be imported from countries like Nubia and Somalia .

Well-known representations of giraffes can be found on predynastic palettes and in the grave of the high official Rechmire of the 18th dynasty . Fleeing animals during a hunt or as heraldic animals can be seen on the magnificent pallets. Shackled animals from punt are presented in the grave of Rechmire . In addition to other animal species, the giraffe is seen in Egyptology as a possible design model for the deity Seth . The giraffe entered the Gardiner list as a hieroglyph under the code E27 .

The word giraffe comes from the Arabic : zarāfa (زرافة) means "the fast one". Another possible interpretation is xirafah , which is sometimes translated as "the lovely one". Julius Caesar had the first giraffe in Europe in 46 BC. To Rome . The Romans called the giraffe camelopardalis because it reminded them of a mixture of camel and leopard . This is where the scientific name Giraffa camelopardalis comes from . At times it was also called camelopard or camel pard in German . The Arab world traveler and geographer Al-Masudi reported the following about them in the 10th century:

“Opinions differ on the origin of this animal species: some believe that it originally came from the camel, others believe that it is the result of a cross between camel and leopard, and still others believe that it is a completely different species acts like horse, donkey and cattle […]. Giraffes from Nubia were already given as gifts to the Persian kings , just as they were then brought to the Arab kings, the Abbasid caliphs and the governors in Egypt . "

The North African populations were hunted early by the Romans and Greeks. Occasionally, giraffes were used by the Romans for animal shows in the Colosseum . In 1486 a giraffe reached Florence as a gift to the Medici , but the animal died shortly after its arrival. Overall, however, the giraffe was little known in Europe until well into modern times.

At the request of the French Natural History Museum in Paris, Zarafa , the first living giraffe in Europe in recent times, was brought to Marseille in October 1826 as a gift from the Egyptian viceroy to the King of France. From there the giraffe was transported to Paris, where it arrived in June 1827. It met with great interest and the museum had 600,000 visitors in the first six months. Balzac later described the decline in interest in the La Silhouette newspaper . The giraffe was 21 years old.

Giraffes were likely a common target for hunters across Africa. The long tendons were used for bow strings and musical instruments, the skins were considered status symbols by many peoples. The meat is tough but edible. The hunting methods of the Africans could not endanger the population. With the arrival of white settlers, giraffes were hunted for sheer pleasure. Big game hunters boasted the numbers of giraffes shot, and the animals were rapidly becoming rarer in many areas. Today giraffes are rare almost everywhere. Only in the states of East Africa are there abundant stocks. Around 13,000 giraffes live in the Serengeti National Park alone . In South Africa they were reintroduced in numerous areas of their original range. The International Union for Conservation of Nature ( IUCN ) has listed all of the giraffes in the Red List as "endangered" since December 2016 ; it currently (as of December 2017) does not differentiate between different species. Previously, the population was “not endangered”. The total number of individuals had decreased from about 163,000 in 1985 to less than 100,000 in 2015. In order to protect the animals, the GFC has declared June 21st as "World Giraffe Day". An unusual settlement of giraffes occurred in 1976 at the Calauit Game Preserve and Wildlife Sanctuary in the Philippines .

- population

The following table shows the development of the giraffe population according to the IUCN. The Giraffe Conservation Foundation also gives a slightly different population figure.

| Art | subspecies | Stock estimate from the 1960s to the 1990s | Inventory estimate 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern giraffe ( Giraffa camelopardalis ) | Kordofan giraffe ( G. c. Antiquorum ) | 3700 | 2000 |

| Nubian Giraffe ( G. c. Camelopardalis ) (+ " G. c. Rothschildi ") | 20,580 (+1330) | 650 (+1670) | |

| West African Giraffe ( G. c. Peralta ) | 50 | 400 | |

| Southern giraffe ( Giraffa giraffa ) | Angola Giraffe ( G. g. Angolensis ) | 10,000 | 17,550 |

| Cape giraffe ( G. g. Giraffa ) | 8000 | 21,390 | |

| Reticulated giraffe ( Giraffa reticulata ) | 36,000-47,750 | 8660 | |

| Maasai giraffe ( Giraffa tippelskirchi ) (+ " G. t. Thornicrofti ") | 66,450 (+600) | 31,610 (+600) |

literature

- Robin Pellew: Giraffes: The gentle giants . In: Geo-Magazin. Hamburg 1978, 8, pp. 26-40. (Scientific report with 13 photos) ISSN 0342-8311

Individual evidence

- ↑ Giraffe | Spelling, meaning, definition, origin. In: Duden. Retrieved May 5, 2020 .

- ↑ Barbara Lang: Why do giraffes have blue tongues? Short question, short answer ( Memento from February 6, 2015 in the Internet Archive ), SWR3, February 6, 2015.

- ↑ Madelaine P. Castles, Rachel Brand, Alecia J. Carter, Martine Maron, Kerryn D. Carter and Anne W. Goldizen: Relationships between male giraffes' color, age and sociability. Animal Behavior 157, 2019, pp. 13-25, doi: 10.1016 / j.anbehav.2019.08.003

- ^ WF Wood, PJ Weldon: The scent of the reticulated giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata). In: Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. Volume 30, No. 10, November 2002, pp. 913-917, doi: 10.1016 / S0305-1978 (02) 00037-6 .

- ^ A b G. Mitchell, JD Skinner: An allometric analysis of the giraffe cardiovascular system. In: Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology - Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology . Volume 154, Number 4, December 2009, pp. 523-529, doi: 10.1016 / j.cbpa.2009.08.013 , PMID 19720152 .

- ^ A b Christopher D. Moyes, Patricia M. Schulte: Tierphysiologie . Pearson Studium, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-8273-7270-3 , pp. 423–424 ( limited preview in the Google book search - English: Principles of Animal Physiology . Translated by Monika Niehaus , Sebastian Vogel).

- ^ E. Brøndum, JM Hasenkam, NH Secher, MF Bertelsen, C. Grøndahl, KK Petersen, R. Buhl, C. Aalkjaer, U. Baandrup, H. Nygaard, M. Smerup, F. Stegmann, E. Sloth, KH Ostergaard, P. Nissen, M. Runge, K. Pitsillides, T. Wang: Jugular venous pooling during lowering of the head affects blood pressure of the anesthetized giraffe. In: American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology . 2009; 297: p. R1058 – R1065, doi: 10.1152 / ajpregu.90804.2008 . PMID 19657096 .

- ↑ Z. Muller, IC Cuthill and S. Harris: Group sizes of giraffes in Kenya: the influence of habitat, predation and the age and sex of worth individuals. Journal of Zoology 306 (2), 2018, pp. 77-87

- ↑ Emma E. Hart, Julian Fennessy, Srivats Chari and Simone Ciuti: Habitat heterogeneity and social factors drive behavioral plasticity in giraffe herd-size dynamics. Journal of Mammalogy 101 (1), 2020, pp. 248-258, doi: 10.1093 / jmammal / gyz191

- ^ A b Robert E. Simmons, Lue Scheepers: Winning by a Neck: Sexual Selection in the Evolution of Giraffe . In: The American Naturalist . 148, No. 5, 1996, pp. 771-786. JSTOR 2463405 .

- ^ I. Tobler and B. Schwierin: Behavioral sleep in the giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) in a zoological garden. Journal of Sleep Research 5, 1996, pp. 21-32

- ↑ PSM Berry and FB Bercovitch: Darkening coat color reveals life history and life expectancy of male Thornicroft's giraffes. Journal of Zoology 287 (3), 2012, pp. 157-160 ( [1] )

- ↑ Alexandre Hassanin, Frédéric Delsuc, Anne Ropiquet, Catrin Hammer, Bettine Jansen van Vuuren, Conrad Matthee, Manuel Ruiz-Garcia, François Catzeflis, Veronika Areskoug, Trung Thanh Nguyen and Arnaud Couloux: Pattern and timing of diversification of Cetartiodactalia, Lauriala (Mammia ), as revealed by a comprehensive analysis of mitochondrial genomes. Comptes Rendus Palevol 335, 2012, pp. 32-50

- ^ Alan Gentry: Family Giraffidae. In: Jonathan Kingdon, David Happold, Michael Hoffmann, Thomas Butynski, Meredith Happold and Jan Kalina (eds.): Mammals of Africa Volume VI. Pigs, Hippopotamuses, Chevrotain, Giraffes, Deer and Bovids. Bloomsbury, London 2013, p. 95

- ↑ a b c Richard Lydekker: On the subspecies of Giraffa camelopardalis: Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 74, 1904, pp. 202-229 ( [2] )

- ↑ a b Peter Grubb: Giraffa camelopardalis. In: Don E. Wilson and DeeAnn M. Reeder (Eds.): Mammal Species of the World. A taxonomic and geographic Reference. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore MD 2005 ( [3] )

- ↑ a b c J. D. Skinner and G. Mitchell: Family Giraffidae (Giraffe and Okapi). In: Don E. Wilson and Russell A. Mittermeier (eds.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 2: Hooved Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2011, ISBN 978-84-96553-77-4 , pp. 788-802

- ↑ a b Isabelle Ciofolo and Yvonnick Le Pendu: Giraffa camelopardalis Giraffe. In: Jonathan Kingdon, David Happold, Michael Hoffmann, Thomas Butynski, Meredith Happold and Jan Kalina (eds.): Mammals of Africa Volume VI. Pigs, Hippopotamuses, Chevrotain, Giraffes, Deer and Bovids. Bloomsbury, London 2013, pp. 98-110

- ^ A b Anne Innis Dagg: Giraffa camelopardalis. Mammalian Species 5, 1971, pp. 1-8

- ↑ David M. Brown, Rick A Brenneman, Klaus-Peter Koepfli, John P Pollinger, Borja Milá, Nicholas J Georgiadis, Edward E Louis Jr, Gregory F Grether, David K Jacobs and Robert K Wayne: Extensive population genetic structure in the giraffe . BMC Biology 5, 2007, p. 57, doi: 10.1186 / 1741-7007-5-57

- ↑ Alexandre Hassanin, Anne Ropiquet, Anne-Laure Gourmand, Bertrand Chardonnet, Jacques Rigoulet: Mitochondrial DNA variability in Giraffa camelopardalis: consequences for taxonomy, phylogeography and conservation of giraffes in West and central Africa. Comptes Rendus Biologies 330, 2007, pp. 265-274, doi: 10.1016 / j.crvi.2007.02.008

- ↑ Colin Groves and Peter Grubb: Ungulate Taxonomy. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011, pp. 1-317 (pp. 64-70)

- ↑ Julian Fennessy, Friederike Bock, Andy Tutchings, Rick Brenneman and Axel Janke: Mitochondrial DNA analyzes show that Zambia's South Luangwa Valley giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis thornicrofti) are genetically isolated. African Journal of Ecology 51, 2013, pp. 635-640

- ↑ Friederike Bock, Julian Fennessy, Tobias Bidon, Andy Tutchings, Andri Marais, Francois Deacon and Axel Janke: Mitochondrial sequences reveal a clear separation between Angolan and South African giraffe along a cryptic rift valley. BMC Evolutionary Biology 14, 2014, p. 219 ( [4] )

- ↑ a b Julian Fennessy, Tobias Bidon, Friederike Reuss, Vikas Kumar, Paul Elkan, Maria A. Nilsson, Melita Vamberger, Uwe Fritz and Axel Janke: Multi-locus Analyzes Reveal Four Giraffe Species Instead of One. Current Biology 26, 2016 ( [5] )

- ↑ Giraffes - there are four species instead of just one Spiegel online, September 9, 2016

- ↑ a b Ingrid Bohms: Mammals in the ancient Egyptian literature (= Habelt's dissertation prints: Series Ägyptologie , Vol. 2). LIT, Münster 2013, ISBN 3-643-12104-0 , pp. 84–87.

- ↑ a b Wolfhart Westendorf: Comments and corrections to the Lexicon of Egyptology . Göttinger Miszellen, Göttingen 1989. pp. 66-68.

- ↑ TS Palmer: Index Generum Mammalium: A List of the Genera and Families of Mammals. North American Fauna 23, 1904, p. 295 ( [6] )

- ↑ ʿAlī Ibn-al-Ḥusain ?? al- ?? Masʿūdī: To the limits of the earth: Excerpts from the “Book of Gold Pansies” . Ed .: Gernot Rotter. Erdmann-Verlag, Tübingen, Basel 1978, ISBN 3-7711-0291-X .

- ↑ Jacques Rigoulet: Historie de Zarafa, la giraffe de Charles X. Bulletin de l'Académie vétérinaire de France 165 (2), 2012, pp. 169–176 ( [7] )

- ↑ New bird species and giraffe under threat - IUCN Red List. IUCN , December 8, 2016, accessed December 8, 2016 .

- ↑ The giraffe is now an endangered species. Die Welt , December 8, 2016, accessed on February 20, 2019 (German).

- ^ The Calauit Game Preserve and Wildlife Sanctuary. In: gov.ph. Palawan Council for Sustainable Development, accessed July 30, 2016 .

- ↑ Africa's Giraffe Subspecies. Giraffe Conservation Foundation, March 2016.

- ↑ Z. Muller, F. Bercovitch, R. Brand, D. Brown, M. Brown, D. Bolger, K. Carter, F. Deacon, JB Doherty, J. Fennessy, S. Fennessy, AA Hussein, D. Lee , A. Marais, M. Strauss, A. Tutchings and T. Wube: Giraffa camelopardalis (amended version of 2016 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018. e.T9194A136266699 ( [8] ), last accessed November 1, 2019

Web links

- Giraffa camelopardalis inthe IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015.3. Listed by: J. Fennessy, D. Brown, 2008. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- Uganda giraffe