Yongle

Yongle ( Chinese 永樂 / 永乐 , Pinyin Yǒnglè , W.-G. Yung-lo ; * May 2, 1360 in Nanjing ; † August 12, 1424 in Yumuchuan, Inner Mongolia ) was the third emperor of the Chinese Ming dynasty and has ruled since the 17th July 1402 the Empire . His birth name was Zhū Dì ( 朱棣 ), his temple name Tàizōng ( 太宗 - "highest ancestor"). The latter was changed to Chéngzǔ ( 成祖 - "Completed Ancestor") in 1538 . Yongle was the fourth son of Emperor Hongwu .

The Yongle Emperor is considered the most important ruler of the Ming Dynasty and is counted among the most outstanding emperors in the history of China . He overthrew his nephew Jianwen from the throne in a civil war and assumed the office of emperor himself. Yongle continued his father's policy of centralization, strengthened the empire's institutions and founded the new capital Beijing . He pursued an expansive foreign policy and undertook several large-scale campaigns against the Mongols . In order to strengthen his influence in East and South Asia, he had a large fleet built and commissioned Admiral Zheng He to carry out diplomatic missions.

youth

Zhu Di was born in 1360 as the fourth son of the future first Ming emperor Hongwu in the capital city of Nanjing . His mother was officially recorded as Empress Ma, but it is entirely possible that a concubine named Gong was his birth mother. If so, then she died shortly after the birth, so that the Empress adopted the newborn Prince Zhu Di as a biological child. At least there is no doubt that the prince's relationship with the empress was very intimate, because after her accession to the throne, Yongle raised the empress mother to a deity and had temples built in her honor.

When Zhu Di was born, his father Zhu Yuanzhang was still a Chinese warlord fighting for power as the Yuan dynasty was about to fall. With the final expulsion of the Mongol dynasty from China, he founded the Ming dynasty as Hongwu in 1368. Zhu Di and his brothers also played a role as extras at the coronation and founding celebrations. At the same time, Nanjing was elevated to the status of the new capital of a united China.

Hongwu closely monitored his sons' education. The crown prince although Zhu Biao deserved the right of way, but since all the Ming princes were taught together with the heir to the throne, all received the same lessons. The master Kong Keren instructed the emperor's sons extensively in the Confucian classics and history as well as in philosophy and ethics. Yongle is said to have been of particular interest to the Qin and Han dynasties , and in later years he is said to have often recited quotations from the First Emperor and the famous Han emperors Gaozu and Wudi .

In 1370, Emperor Hongwu created imperial principalities for his sons on the borders of the empire. With that, Zhu Di was made Prince of Yan 燕王at the age of ten ; that region in the north whose seat of government was the former Yuan capital Dadu, which was now called Beiping (Northern Peace) . Since he was still too young, his father appointed a governor in Beiping at the same time that Zhu Di was given the Yan Royal Seals . Now the new prince of Yan received his own teachers who had to prepare him for his future role as regional prince of the north.

Prince of Yan

Even as a young man, the court considered Prince Zhu Di to be one of the most capable sons of the Hongwu Emperor, who received special attention from his father. Zhu Di showed himself to be a gifted student with a quick grasp. He was of tall athletic stature and enthusiastic about hunting, which is why his father liked to spend time with his fourth son. In 1376 the prince was married at the age of sixteen. He married Lady Xu, daughter of General Xu Da . The general had played a major role in Hongwu's conquest of China and had now become not only the father-in-law of an imperial prince, but also Zhu Dis's governor in Beiping and supreme commander of the northern armies.

In 1380, Zhu Di and his young family (the first son Zhu Gaozhi was born in 1378) moved from the capital Nanjing to Beiping in the Principality of Yan. The prince now moved into the old palaces of the Mongol emperors, which his father had once sealed. The residence was not in the best condition, but had dimensions similar to the Imperial Palace of Nanjing, which meant that the prince now resided far more splendidly than any of his brothers in the other principalities.

With Yan, Zhu Di had received the most important of all principalities and wanted to savor his new power. He created a staff of experienced advisors around himself and tried to manage Yan in an exemplary manner. Still at his side was his father-in-law Xu Da, who had stayed in Beiping since 1371 and had developed the city into the main military base in the north. From there he had already undertaken several successful campaigns against the Mongols along the borders. The veteran general instructed Zhu Di in war tactics, military organization and defense strategy. The prince then undertook maneuvers with the general year after year in northern China. Zhu Di reported successful, albeit small, expeditions to Inner Mongolia to the emperor . General Xu Da became seriously ill in 1384 and was called back to Nanjing. He left his son-in-law a well-trained army of about 300,000 men, who now transferred their loyalty to the prince.

Zhu Di stayed in Beiping for nineteen years and had a well-organized area. During this time, Crown Prince Zhu Biao died in 1392, and later also Zhu Dis's other older brothers. So the prince was hopeful that he would succeed the old Hongwu emperor in office. But Hongwu had become more and more capricious and unpredictable. He mistrusted his numerous sons, and he no longer excluded Zhu Di from them. Zhu Di could not rely on his past good relationships with his father. He waited to see who the old emperor would appoint as his designated successor. Contrary to his expectations, his father chose his grandson Zhu Yunwen .

In 1398, Emperor Hongwu died and his grandson ascended the dragon throne as Jianwen. The new government got off to a bad start for the Prince of Yan, as the Jianwen Emperor specifically forbade his eldest uncle, Zhu Di, from attending his father's funeral in Nanjing. That shouldn't be the only humiliation Zhu Di experienced from his nephew, the emperor. Numerous followed. The Imperial Court shared the Hongwu's distrust of the influential princes on the empire's borders, given their enormous military power and the vast financial resources they had at their disposal. Emperor Jianwen and his advisors sought to reform the imperial system and to curtail the princes' powers. But this inevitably met with resistance from the princes. Zhu Di was the oldest member of the imperial clan, and he has now been turned to by his brothers and nephews for a decisive response. This was not inconvenient for Zhu Di, as he saw himself as the rightful heir to the throne.

Seizure of power

After Zhu Di's attempt to obtain an audience with the emperor in Nanjing failed, he decided to act. In 1399 he declared war on Nanjing with the justification that he had to "free his imperial nephew from the clutches of evil advisors" . The civil war initially went very well for the Jianwen emperor. He had more troops, more money and a better strategic position. The imperial army quickly stood before Beiping, which was defended by Zhu Dis's wife, Lady Xu. But the well-developed city withstood the onslaught.

The Prince of Yan then changed his military strategy. First, he increasingly relied on his Mongolian cavalry . As Prince of the North, numerous Mongol tribes surrendered there during his twenty-year term, and they were now unreservedly loyal to him. The imperial cavalry could not withstand this elite force. Second, in contrast to the Jianwen emperor, Zhu Di now commanded his army himself, which earned him great respect in the enemy army and also in the population. The third point was to make the Prince of Yan emperor. Instead of trying to reach Nanjing via the well-defended Imperial Canal , the prince led his army westward across the country. In open battle, the Jianwen's troops were unable to defeat the prince. The breakthrough came in the spring of 1402. Zhu Di stood at the lower yangzi . The emperor's negotiators made secret pacts and the commanders of the river army defected. On July 13, 1402, defectors opened the city gates of the capital Nanjing. Allegedly, Emperor Jianwen started the fire in the palace himself to commit suicide with his wife and eldest son.

With that, Zhu Di decided the civil war for himself. He ascended the throne himself on July 17, 1402 at the age of forty-two and adopted the government motto Yǒnglè , which means perpetual joy . According to tradition, his birth name Zhu Di became a taboo because the Son of Heaven no longer had a name as God. The Jianwen reign has been removed from the historical records, the missing time simply added to the Hongwu era. First, the new emperor began a large-scale cleanup. He had all of his nephew's advisors and their families executed. Large parts of the official staff were also eliminated. Many committed suicide voluntarily because they despised Yongle's usurpation . Another serious problem were the two remaining sons of Jianwen and his three brothers. These, too, were all executed as potential rivals. Around 20,000 people fell victim to the purges in the capital.

Domestic politics

Despite the bloody beginning, the reign of Emperor Yongle went down in Chinese history as a heyday of the empire. As an era of flourishing prosperity and inner strength, led by a strong emperor and competent ministers.

Imperial institutions

The first official act of the Yongle era concerned the privileges of the Ming princes. With the strength of his armies behind him, Yongle immediately stripped the princes of control of their troops and took away much of their financial resources. This ensured that a civil war would not be repeated. Bit by bit, Yongle disempowered his male relatives, a process that finally came to an end under his grandson Xuande .

First, the new emperor moved into the restored palaces of Nanjing and made the power center of his former enemies his own. Over the course of a decade, he replaced practically all senior officials or sent them to distant provinces far from the capital. The entire administrative apparatus was recruited with loyal men who had often served at Yan's court.

The imperial bureaucracy was a major focus of the emperor. The centralization of the administration and thus the concentration of power in the hand of the Son of Heaven was Yongle's constant drive. From the emperor's personal advisory staff, he formed a new powerful institution, the Neige . This privy councilor, better known as the Grand Secretariat, was made up of administrative experts who did their job inside the palace and who only assisted the ruler in dealing with state affairs. The Grand Secretaries of Neige not only enjoyed enormous prestige, but were also able to unite great power in later times.

Emperor Yongle liked to see himself as a martial ruler, but also valued classical Chinese education. A talented calligrapher himself , he promoted the literary class and the imperial official exams . Yongle brought particularly talented candidates to his court. In order to facilitate the work of the scholars, he had the well-known Yongle encyclopedia created , which was to encompass the entire knowledge of the time. Over 2,000 officials worked for five years to compile this work, which when completed comprised 22,938 chapters with more than 50 million words. The Yongle encyclopedia was far too extensive to ever be printed regularly. Therefore, only a few copies were made. The emperor kept the original manuscript in the palace to use it for himself and his advisors.

Eunuchs

The eunuchs were part of the imperial court at all times. Only the imperial family was allowed to use such persons. The eunuchs were particularly valued for their loyalty, as they were either sold to the court as children by their families or had no family connections at all. So they were completely dependent on the ruler. Like the palace servants, the eunuchs were employees with the rank of civil servant, with numerous opportunities for advancement. These special servants surrounded the emperor and his family constantly, even in the most private moments.

The Yongle Emperor increasingly relied on eunuchs, both as palace servants and as representatives of his imperial authority. He not only ensured an excellent education for the court eunuchs , but also founded the so-called twenty - four offices of the palace administration, which were manned exclusively by eunuchs. These twenty-four offices were made up of the twelve supervisory boards, the four agencies and the eight sub-offices . All these departments were occupied with the organization of the palace life, i.e. the administration of the imperial seals, horses, temples and shrines, the procurement of food and objects, but also cleaning and gardening were among the tasks of the eunuchs.

In 1420, Yongle expanded the work of his eunuchs to include secret service activities. He created the Eastern Depot (Dongchang), a notorious secret service where eunuchs were relentlessly busy checking the officials to see if they were corrupt or disloyal.

The Eastern Depot was supplemented by the guards in brocade uniforms (Jinyi wei), an elite group of bodyguards of the emperor. The brocade dress guard consisted exclusively of deserving soldiers with great combat experience and served as military police. She monitored the Eastern Depot prison and, at its request, carried out arrests and interrogations. The guard in brocade uniforms was generally responsible for all sensitive government orders. Through this tight network of intelligence surveillance, Yongle wanted to make sure he was informed of everything inside and outside the palace. In this way he was able to work quickly against possible rebels, but also to check whether the information and reports that had been sent to him were true.

Beijing

After his accession to the throne, Yongle initially resided in Nanjing. There he had the Bao'en Temple with the famous porcelain pagoda built as the first major construction project in honor of his mother . He renamed his old residence Beiping Shuntian ( Obedient to Heaven) .

As early as 1406, Yongle announced that he would move the capital to the north. He renamed Shuntian in Beijing, the northern capital . The construction plans were extensive. The emperor found both the imperial palace of Nanjing and the old palaces of the Mongols to be too small and not representative. The entire inner city of the former Dadu of the Yuan khans was razed to the ground. Beijing should rise from scratch. As a representation of the world order, it comprised four districts that were nested in a square. In the center, the Purple Forbidden City was built, which was about twice the size of the old palaces. Followed by the imperial city, in which there were imperial parks, the western lake palaces and other residences for princes and officials. This was followed by the inner and outer residential towns for the normal population.

At the end of the Yongle government, Beijing and its outskirts already comprised around 350,000 residents. Since 1408, the emperor spent most of his time in Beijing personally overseeing the construction. He left his Crown Prince Zhu Gaozhi in Nanjing, who headed a provisional Regency Council there and took care of the day-to-day routine. Nanjing was officially relegated to a secondary residence in 1421 and had to give way to Beijing as the seat of government.

The decisive factors for relocating the capital were, on the one hand, that Yongle wanted to leave the region of Nanjing, as it seemed to him to be the least trustworthy. His nephew Jianwen had ruled in Nanjing and there were still forces working against him there. His old residence in the north was also his power base, where there were numerous powerful families who owed him the rise. On the other hand, the Mongol problem was still present. In distant Nanjing, he was cut off from the events on the borders. Since Yongle was planning an offensive policy against the northern areas, he needed close proximity to the steppe and short reaction times for the army. In Beijing there were both domestic and foreign policy advantages.

View over Yongle's Palace, the Forbidden City

Nine Dragon Wall in Beihai Park

Emperor Yongle also went down in history as one of the most building-active sons of heaven. In addition to the new palace district of Beijing , he had numerous large temples built in his new capital, including the Temple of Heaven for the sacrifice to the highest cosmic order and many more well-known buildings. In order to be able to supply Beijing with sufficient food from the south, Yongle had the Imperial Canal restored and expanded to reach the city. The vast quantities of goods that Beijing devoured soon made the canal again the main trade route of the empire.

The emperor was also active as a builder outside the capital. His building activity in the Wudang Mountains is particularly noteworthy . There he built a Daoist temple for over a million silver ounces , which was even elevated to a state shrine . The Wudang Temple was dedicated to a Daoist god of war, quickly attracted large numbers of pilgrims and is known to this day as the center of kung fu .

Foreign policy

Emperor Yongle sought to consolidate China's position in the world. He did not avoid foreign policy threats and enemies, but tried to render them militarily harmless. His rule was characterized by a high sense of mission towards the outside world. The emperor not only wanted to make it clear to all neighboring regions that the Middle Kingdom had regained strength under a Han Chinese dynasty, but also wanted to show that China was the hegemonic power of Asia, with the Son of Heaven at the center of the world order .

Mongol campaigns

The China of the Ming period felt constantly threatened by the Mongol tribes living in the north. During the Yongle era, the Yuan khans had been driven out only forty years ago. Therefore, in China, an invasion of the descendants of Genghis Khan to regain power or possible plundering campaigns were viewed as a realistic threat. Yongle tried to remove this potential danger. Many Mongols had remained in China after 1368 and became loyal subjects of the Ming. The emperor was able to use this group for himself, on the one hand as elite soldiers, on the other hand as instruments against their cousins from the steppe. Most of the loyal Mongol families were settled in buffer zones on the northern border . But Yongle tried to pacify the hostile steppe dwellers with honorary titles and gifts. This rarely succeeded.

The Mongols had lost their former size and lived split into two large political blocs, the western and eastern Mongols. The Western Mongols, also known as Oirats , were a fairly stable entity, but further away from China. The Chalcha in the east, in turn, lived directly on the northern borders of China and in this respect represented an immediate danger, but on the other hand were divided. Yongle wanted to prevent any military reunification of the Mongolian forces and further weaken the Mongols.

First he extended the imperial borders far to the northeast, where he founded the Chinese province of Manchuria . The Jurchen of northern Manchuria were brought together in a protectorate by concluding alliance and friendship treaties with them. This was supposed to increase the pressure on the Mongols. However, when the Mongol general Arughtai was able to unite numerous tribes of the eastern Mongols and even had an envoy from the Ming executed, Yongle increased his military ambitions. In large-scale campaigns, he attacked the Mongol territories. Yongle personally commanded five campaigns against the Mongol tribes: 1410, 1414, 1422, 1423 and 1424. The troop strength was said to be around 250,000 men, whom the emperor led deep into Mongolia . In doing so, he inflicted devastating defeats on the Mongols.

Although Yongle's Mongol campaigns were invariably successful, they were never crowned with final victory. The capture of Arughtai could not be achieved, and again and again the Mongols managed to reorganize and to set up new troops for defense. Yongle was able to keep the northern tribes in check and conquer new areas in the north, but neither did he achieve a final solution to the border problems in the north.

Annam War

In 1400 the usurper Lê Loi killed the King of Annam from the House of Tran . Various parties then proclaimed their own king and sent envoys to the Ming court to legitimize their rule. Little was known at the imperial court about the events in Annam and the representative of the Lê party was accepted with the information that the Tran family had died out.

However, when Yongle took office, a member of the Tran family filed a claim to the Annamese throne and asked the emperor for help. Yongle also recognized his predecessor's mistake and asked Lê to cede the throne to the rightful heir. Lê accepted the request. When the legitimate Tran prince, accompanied by a Chinese expeditionary army and a Ming envoy, entered the country in 1405, all were massacred on Lê's orders. Since there was no other representative of the Tran, Yongle decided to integrate Annam as a new province into the empire and to punish Lê.

In 1406 a Ming army marched into Annam and annexed the country, Lê went into hiding. Yongle believed that since Annam had been a Chinese province from the Han to the Tang times, it was a natural part of China anyway. The emperor also wanted to demonstrate China's military strength. But the population stubbornly resisted annexation to the Middle Kingdom and gave Lê the opportunity to resume the fight. A long war against rebel armies was the result.

The Annam War is considered to be the Yongle Emperor's biggest mistake, as Annam was neither economically nor strategically attractive to China. His grandson Xuande took a more moderate stance towards Annam, ended the useless war and legitimized the Lê dynasty as the new ruling house of Annam.

Treasure fleet

See main article: Zheng He

Of all of the Yongle's projects, the treasure fleet's rides are some of the most impressive. Immediately upon his accession to the throne, the emperor gave the order to build a fleet that consisted of large junks (see treasure ship ) and allegedly transported 33,000 people with around 300 ships . A major goal of his naval policy was to inform the seafaring countries that he was now the rightful ruler of China's throne. Foreign rulers should be intimidated by the size of the fleet, reflecting the superiority and splendor of China. The foreign kings were invited to come personally or represented by an ambassador to the imperial court of the Ming in order to submit to the Son of Heaven with the threefold kowtow .

Yongle chose his court eunuch, Zheng He, to be in command of his treasure fleet. Zheng He came to Yan's court as a youngster and there earned the prince's trust. During the civil war, Zheng He successfully commanded an army company, and after the Yongle took office, Zheng He remained one of the emperor's most important confidants. Zheng He was suitable as an expedition leader because he belonged to the loyal group of eunuchs and because he was a Muslim. Yongle primarily wanted to contact areas where Islam was the predominant religion. Therefore, he passed the command to someone who was not only a trustworthy servant, but also knew about the peculiarities of foreign races.

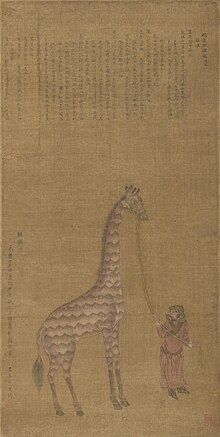

On Yongle's instructions, Zheng He undertook six long journeys between 1405 and 1422, which took him to the coasts of Arabia and Africa . In doing so, however, he traveled routes that the Chinese had been using for centuries with their junks, which is why the term “expedition” must be considered rather inappropriate. What was new, on the other hand, was the enormous size of the fleets, that the emperor himself was the client and that the profit was completely secondary in this venture. Zheng He was supposed to do diplomacy and proclaim the splendor of China to all the countries visited. With great satisfaction, Emperor Yongle was able to welcome countless embassies from all over South Asia in the capital, who willingly paid their “tribute” to the Son of Heaven. So Yongle actually succeeded in enormously increasing its prestige abroad.

The main political goal was overachieved, but the cost blew all trade profits. The treasure fleet was able to transport enormous quantities of goods, but these were used solely to refinance maintenance costs. In addition, most of the items transported were intended as gifts for the emperor, so they were never sold and remained in the possession of the court. Among other things, Zheng He bought a set of glasses from Venice for his short-sighted master in Jeddah , a European invention that had hitherto been completely unknown in China. As overwhelming and successful as the sea voyages of Zheng He were, they also put a huge burden on the state budget . As a result, many advisors and ministers of the emperor already in Yongle's time objected to a merchant fleet that had to be borne solely by the state and brought nothing but fame. This is why the elite of civil servants spoke out in favor of leaving private maritime trade.

Korea and Japan

In Korea was in 1392 in a coup, the Joseon Dynasty was founded. Even as a prince in Yan, Zhu Di had good contacts with the Korean royal court. After Yongle's forcible takeover, the new Joseon dynasty was only too ready to accept regime change in China. Since Korea was the richest Chinese vassal , it was also the most important of all vassal states. Yongle was grateful for his swift submission to his suzerainty and gave him rich gifts at audiences of his envoys.

Yongle also sought good contacts to Japan . Relationships that were often strained in the past should normalize. Yongle also planned to draw Japan into the sphere of his influence. But since the Japanese were never and never became a Chinese vassal, they always appeared with great self-confidence . A good opportunity for a political offer presented itself when Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu 1403 sent an embassy to Yongle. Since he was in need of money, the shogun tried to bring the very profitable trade in China under his control. Yongle offered him a monopoly of trade and financial benefits if he formally submitted. Indeed, Yoshimitsu assumed the title of King of Japan and accepted numerous gifts from Yongle, which the Shogun proudly presented. Ultimately, however, the title remained an office without any relevance and the influence of the Ming remained negligible after Yoshimitsu's death, and his successor showed far less interest in trade with China.

Death and succession

The Yongle Emperor died on August 12, 1424 during his last campaign against the Mongols in Inner Mongolia at the age of 64 years at a stroke . The emperor had suffered several minor strokes in previous years, but had recovered each time. In 1424, already physically battered, he set out with his army from Beijing to Mongolia. Apparently he suffered one last serious attack on the way back, in the course of which he passed away four days later. Shortly before his death he was still able to give his general Zhang Fu one final instruction: hand over the throne to the crown prince; follows the etiquette of the founder of the dynasty on matters of burial clothing, ceremonies and sacrifice. His body was locked in a tin coffin and returned to Beijing, where state mourning was declared and the new emperor initiated the official funeral ceremonies.

Yongle had long been occupied with his last resting place. One thing was clear to him: he did not want to rest in Nanjing , but rather to create a new resting place in the north for himself and his successors. In the summer of 1407, Empress Xu died and the Yongle Emperor ordered the geomancers to start looking for a location for the imperial mausoleums. 50 km north of the capital, they found what they were looking for on the Mountain of Heavenly Longevity . There the emperor built the Changling mausoleum for himself and his wives , which means the home of eternal lingering .

The Changling 長陵 is monumental in size. It is actually the largest of the Ming Imperial mausoleums and is counted among the largest imperial tombs in China. It is a scaled down version of the Forbidden City, with two large entrance gates, each followed by a forecourt. In the center is the sacrificial hall (hall of heavenly favor), which is an image of the hall of highest harmony . Then come the sacrificial altar and the soul tower, followed by a tomb tumulus with a diameter of three hundred meters. Under this is the underground palace of the dead emperor. Yongle was buried there with a large number of precious grave goods . The Changling is still unopened today. After Yongle's death, all Ming emperors had their mausoleums built according to the Changling scheme in the same auspicious valley. Today the valley is known and valued as the Ming Tombs District .

The Yongle Emperor was succeeded by his son Zhu Gaozhi as Hongxi , who only ruled for a very short time. Therefore, Yongle's favorite grandson, Zhu Zhanji, soon ascended the throne. As Xuande , he was to continue his grandfather's politics. The Yongle Emperor is considered a very successful ruler, but he left his son largely empty state coffers. The construction of a huge new capital, an expensive foreign policy and a highly costly naval policy had overstretched China's public finances. Nevertheless, the Middle Kingdom was stronger internally and externally than it had been for five hundred years. Only the still flaming conflict in Annam put a strain on the Ming administration. The Yongle Era went down in history books as the beginning of a two-hundred-year era of internal peace in China.

His son gave Yongle the temple name Taizong ; a name of honor granted to a strong successor to a dynasty founder, with the honorable one being considered a co-founder. Emperor Jiajing later changed the name to Chengzu . The component zǔ祖 is a particularly honorable word for ancestor and is actually only available to the dynasty founder. Jiajing thus increased the status of the third Ming emperor and for the first time in history granted the nickname zǔ祖 a successor to a dynasty founder.

Remarks

- ↑ a b c These figures come from traditional Chinese historiography, in which the information is often greatly exaggerated for propaganda reasons.

literature

Ming Dynasty:

- Patricia Buckley-Ebrey: China. An illustrated story. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-593-35322-9 .

- Frederick Mote: Imperial China 900–1800. Harvard, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 0-674-44515-5 .

- Ann Paludan: Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors. Thames & Hudson, London 1998, ISBN 0-500-05090-2 .

- Denis Twitchett , Frederick W. Mote: The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 7. The Ming Dynasty 1368-1644. Part 1. University Press, Cambridge 1988, ISBN 0-521-24332-7 .

- Denis Twitchett: The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 8. The Ming Dynasty 1368-1644. Part 2. University Press, Cambridge 1998, ISBN 0-521-24333-5 .

Emperor Yongle:

- Louise Levathes: When China Ruled the Seas. Oxford Univ. Press, New York 1996, ISBN 0-19-511207-5 .

- Shih-Shan Henry Tsai: Perpetual Happiness. The Ming Emperor Yongle. Univ. of Washington Press, Seattle 2001, ISBN 0-295-98124-5 .

Beijing:

- May Holdsworth: The Forbidden City. The Great Within. London 1995, Odyssey, Hong Kong 1998, ISBN 962-217-590-2 .

- Susan Naquin: Beijing Temples and City Life. 1400-1900. Univ. of California Press, Berkley 2000, ISBN 0-520-21991-0 .

- Ann Paludan: The Imperial Ming Tombs. Yale University Press, New Haven 1981, ISBN 0-300-02511-4 .

Web links

Documentation:

Buildings of the Yongle in Beijing:

- The Forbidden City

- The imperial ancestral temple

- The Jingshan Park

- The Temple of Heaven

- The drum tower and the bell tower

- The Confucius Temple

Ming tombs:

Yongle's buildings outside Beijing:

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Jianwen |

Emperor of China 1402–1424 |

Hongxi |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Yongle |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Zhu Di; Chu Ti; Taizong; T'ai-tsung; Chengzu; Ch'eng tsu; Yung-lo |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Emperor of China (1403–1424) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 2, 1360 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Nanjing |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 12, 1424 |

| Place of death | Yumuchuan , Inner Mongolia |