Hongwu

Hóngwǔ洪武 (birth name 朱元璋Zhū Yuánzhāng , temple name太祖Tàizǔ ; * September 21, 1328 ; † June 24, 1398 ) was the founder of the Ming Dynasty . He ruled China as emperor from 1368 to 1398 .

Zhu Yuanzhang, who later became the Hongwu emperor, came from a very simple farming background. Due to strong ambitions, he achieved rapid ascent within the Red Turbans rebel movement , and finally the fall of the Yuan dynasty and thus the expulsion of the Mongol ruling house . In 1368 he founded the Ming dynasty based on the model of the first Han emperor Gaozu and shaped the institutions of the empire as they were to endure until the end of the imperial era. Because of his great achievements, he is counted among the most important emperors in China.

Rise and struggle for power

Zhu Yuanzhang was born in 1328, the youngest of six children. His father Zhu Shichen fled Nanjing to Anqing because he could not pay the taxes there. His grandfather was a gold panner and his mother's father was a popular sorcerer. In 1344, most of Zhu Yuanzhang's family died of a plague epidemic , so that as an orphan he was forced to enter a Buddhist monastery in order not to starve. Here he learned to read and write and came into contact with higher education for the first time.

In 1352 he left the monastery and joined the Red Turbans, because riots broke out across China and the power of the Yuan khans began to wane. With the help of a small group of friends, he made his way up within the rebel army, and quickly led his own force with which he attacked enemy garrisons and cities. Through his successes, rebel leader Guo Zixing became aware of him, to whose personal staff Zhu Yuanzhang now belonged. Zhu's marriage to Lady Ma, the adopted daughter of Guo Zixing, made Zhu Yuanzhang more and more important, and he became a new warlord in China. With his own 30,000-strong army, he set out for the southeast and captured a number of cities along the lower Yangtze . After the death of his father-in-law in 1355, he increasingly pursued his own goals, although he formally supported the claim to power of the Red Turbans. In 1356 he conquered the city of Nanjing after several failed attempts and made it his new base. By 1367 he had conquered practically all of southeast China, with an army of around 250,000 men. In the same year, the head of the Red Turbans, regarded by the followers of the sect of the White Lotus , on which the Red Turbans were based, as a representative of the Buddha Maitreya , stayed with him as a guest. In his care, the guest died under unexplained circumstances, and immediately after his death, Zhu Yuanzhang proclaimed his claim to the imperial throne. He sent his armies north to attack the Mongol capital Dadu (today's Beijing). The last Mongol emperor Toghan Timur fled to Mongolia at night with the imperial seal, which finally ended the rule of the Yuan. Zhu Yuanzhang had Dadu's palaces sealed, all archives and collections brought to Nanjing, the walls razed and the city name changed to Beiping (Northern Peace).

Creation of a new dynasty

On September 14, 1368, Zhu proclaimed the establishment of a new imperial dynasty as the victor of the civil war , which he named Da Ming大 明, which means the great brightness . He himself chose the government motto Hongwu ("comprehensive warriorism"). In order to legitimize the Confucian tradition, he detached himself more and more from the red turbans that had made his rise possible.

Hongwu was unsure whether Nanjing should really be his new capital, for never before had the entire empire been ruled from so far south. First he had the old capital of the Song dynasty Kaifeng and the capital of the Han and Tang dynasties Chang'an (now Xi'an) explored, then he decided on his own birthplace, Fengyang , a few hundred kilometers northwest of Nanjing. Here he wanted to build his new residence, the Middle Capital ( Zhongdu ). The massive construction work began in 1369. First he had his parents build their own imperial mausoleums and then build lavish palaces and wide city walls. In 1375 he visited the almost completed facilities in the Middle Capital for the first time. He was shocked by the cost and useless luxury of the buildings. He had the work stopped and within a few years the facilities fell into dumps. The emperor intended to stay in Nanjing and had the city splendidly decorated as an imperial residence. The Forbidden City of Nanjing was built east of the old town , and the entire city was greatly expanded and surrounded by a 35-kilometer wall. The southern capital grew to become the center of China, with a population of around half a million people.

Structures of the new government

The new Ming government needed its own administrative structure . The once well-developed bureaucracy of Kublai Khan had been neglected by his successors and finally collapsed completely. Hongwu not only wanted to tie in with the Chinese yuan institutions, but also with the traditions of the Song era. However, he did not form a mere copy, but a completely independent, completely customized bureaucracy. In 1380 he had his chancellor Hu Weiyong executed and abolished the title of chancellor . With this he ended a tradition of office that had existed without interruption since the First Emperor , albeit with a constant loss of power. He himself filled the vacuum created after the end of the chancellery, which is why the Hongwu era is also seen as the beginning of Chinese absolutism .

Administrative structure

- The Grand Secretariat

- Also called Neige (privy councilor). Actually only created by Emperor Yongle , but Hongwu laid the foundation for the decline with his personal advisory staff . This was manned by three to six grand secretaries, who assisted the emperor in supervising and coordinating the work of the six specialist ministries and thus united great power within the government.

- The six ministries

- Ministry of Appointments ( Ministry of Personnel), Ministry of Finance , Ministry of Rites , Ministry of War , Ministry of Justice and Ministry of Public Works .

- The censor

- Was staffed with two senior censors and a few sub-censors and comprised four subordinate offices. It employed 110 investigators who observed the administration throughout the empire and were supposed to punish cases of ineptitude, perversion of justice and corruption. They were also empowered to criticize the highest government officials and even the emperor for their actions. At the time of Hongwu, the censorate did not yet have far-reaching powers; it was only with Emperor Xuande that it would become a powerful authority.

Hongwu created an almost autocratically centralized system that served the emperor's direct exercise of power and was a good fit for ambitious and hardworking rulers like Hongwu. However, it was to become problematic with weak emperors who were not interested in politics. In order not to let power fall to ambitious eunuchs , Hongwu banned them from interfering in politics on the death penalty. He even tried to withhold reading and writing from them, and banners saying Eunuchs have no interest in the affairs of the state were hung up in the palace as reminders. Only a small group of particularly trustworthy palace eunuchs were allowed to head the private secretariat of the emperor. There they were busy sifting through the extensive incoming documents, presenting them to the emperor and then archiving them. Hongwu also introduced the custom of beating officials. In the case of legal offenses, the civil servants were beaten with a wooden slat; serious violations are said to have resulted in deaths. This was in stark contrast to the practice of all previous dynasties of explicitly exempting officials from humiliating punishments such as corporal punishment.

Domination and personality

After Hongwu had appointed himself the first Ming emperor and completely conquered central China, he began an aggressive foreign policy. An invasion of Mongolia, on the other hand, failed because Mongolian troops, who had already defeated the Red Turbans in northern China, remained loyal to the Yuan and decisively defeated the Ming Army in 1372. This defeat caused Hongwu to set up a permanent line of defense on the northern border from 1378, militarily monitored and administered by his second, third and later fourth son, the princes of Qin, Jin and Yan, and a defensive strategy in his foreign policy orientation until 1385 . Subsequent reduced expansion efforts ended as early as 1393 as a result of further purges in the government. Hongwu maintained this defensive strategy until his death in 1398. Only the expansion of power to overseas territories was not Hongwu's goal from the start. As early as 1371 he decreed a ban on attacking overseas nations for no reason and wrote a list of 15 nations that future rulers of the Ming should not conquer. This list included the first four Korea , Japan and the Ryūkyū Islands , both Great and Small - all traditionally tributary nations of China. The fifth nation was Annam (today's central and northern Vietnam), which the Yongle Emperor, the fourth son of Hongwu and third emperor of the Ming, tried to conquer despite his father's prohibition. The other nations were Cambodia , Thailand , Champa (in today's South Vietnam), Semudera (on the north coast of Sumatra ), Xiyang (Chinese name for areas on the Indian Ocean), Majapahit (in the center and east of Java ), Pahan (in today's Malaysia ), Pajajaran (in western Java ), Sanfoqi (in southern Sumatra) and Brunei .

His domestic policy was dominated by economic reconstruction. There were innumerable building and irrigation projects that opened up half a million to five million hectares of land per year. Grain tax receipts tripled within six years. It is estimated that up to a billion useful trees have been planted in 20 years. The result was enormous population and economic growth.

As he got older, Emperor Hongwu became more and more of an autocrat who constantly feared conspiracies and intrigues against him. Around 45,000 people fell victim to the purges. The sharpest of these actions were directed against his Chancellor Hu Weiyong. In 1380 he sentenced Hu to death after Hu was suspected of forming civil servants and conspiring with strangers to assassinate Hongwu. Though frequently cited, the exact allegations against Hu remained unclear and to this day there is no way to judge his guilt or innocence. In the 1380s and 1390s, around 30,000 people died in this purge alone, suspected either as supporters of Hu or through the principle of kin liability, which has long been common in China. The mentioned purges from 1393 claimed another 15,000 victims. In his own words, Hongwu felt an urge to rid the world of unjust people. He writes himself:

“In the morning I punish some; in the evening others commit the same crime. If I punish them in the evening, there will be new transgressions the next morning. The corpses of the first evildoers have not yet been removed, as the next ones are already following their path. The more severe the punishment, the more transgressions. I must be vigilant day and night. There is no help from this situation. If I impose mild sentences, these people will commit even worse crimes. How are people supposed to lead a peaceful life outside of government? What a difficult situation! If I punish these people, I am considered a tyrant. If I show them leniency, the law loses its effect, order crumbles, and the people consider me an incompetent emperor. "

It is reported that a Confucian scholar was very dissatisfied with the extreme measures taken by his emperor and went to the capital to clarify his mistakes to Hongwu. When he was admitted to the audience , he brought his own coffin with him. After severely criticizing the emperor, he lay down in the coffin awaiting his death sentence. Instead, the ruler was so impressed by the man's courage that he let him go.

Compared to earlier times, under Hongwu the state turned more and more to agriculture. The emperor understood little about economics and took over from the Confucians the point of view that trade was of no value to society and a hindrance to achieving the status of the noble, the highest intellectual level of Confucian thought. In a typical Confucian perspective, Hongwu wished that agriculture was the source of all human wealth. China experienced a revival of rural life, especially during his reign. His origins already implement this trend as he was born into a rural family himself.

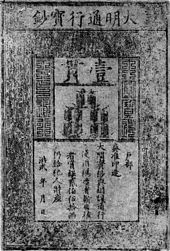

Under Hongwu, the use of paper money came back into fashion, which was developed by the Song and at times used particularly successfully by the Yuan. In 1374 the first Ming paper money was put on the market. It could not be exchanged for gold, silver or any other medium of exchange. Despite the knowledge of the Song and Yuan's experience with paper money, 1450 silver had already replaced the now worthless paper money.

Despite personal mistakes, Hongwu's historical record is positive. He was a successful emperor who was serious about people's problems and dutifully worked. After 30 years of reign he left a very rich country and had 36 sons and 16 daughters. He created powerful positions for his sons in specially created principalities along the borders. He intended to keep the princes away from the capital and the government. A system that should not last long, because at the latest his son Yongle and his great-grandson Xuande dismantled the Ming princes in their privileges, since they feared them as rivals for power and potential rebels.

The succession to Hongwu was marked by disputes. After the early death of his eldest son Zhu Biao, he named his son, his grandson Zhu Yunwen, crown prince. In doing so, however, he violated the traditional line of succession , according to which the eldest living son of an emperor should always succeed him. Hongwu's fourth son, Zhu Di, did not accept the decision. Since his older brothers, the princes of Qin and Jin, had also died before their father Hongwu, Zhu Di invoked his right as the eldest living son of Hongwu after Hongwu's death and in 1399 went into open rebellion against his nephew, the new emperor Jianwen . After Zhu Dis's victory over this, he appointed himself emperor in 1402 under the motto Yongle. The fate of Jianwen, however, remains unclear to this day.

When Hongwu finally died, he was buried on the Zhongshan near Nanjing , making him the only Ming emperor who does not rest near Beijing.

Calendar Era (Hongwu Era)

| 洪武 Hongwu | 1 year | 2 years | 3rd year 年 | 4th year | 5th year | 6th year | 7th year | 8th year | 9th year | 10th year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Western calendar |

1368 | 1369 | 1370 | 1371 | 1372 | 1373 | 1374 | 1375 | 1376 | 1377 |

| 干支 Ganzhi | 戊申 | 己酉 | 庚戌 | 辛亥 | 壬子 | 癸丑 | 甲寅 | 乙卯 | 丙辰 | 丁巳 |

| 洪武 Hongwu | 11th year | 12th year | 13th year | 14th year | 15th year | 16th year | 17th year | 18th year | 19th year | 20th year |

|

Western calendar |

1378 | 1379 | 1380 | 1381 | 1382 | 1383 | 1384 | 1385 | 1386 | 1387 |

| 干支 Ganzhi | 戊午 | 己未 | 庚申 | 辛酉 | 壬戌 | 癸亥 | 甲子 | 乙丑 | 丙寅 | 丁卯 |

| 洪武 Hongwu | 21st year | 22nd year | 23rd year | 24th year | 25th year | 26th year | 27th year | 28th year | 29th year | 30th year |

|

Western calendar |

1388 | 1389 | 1390 | 1391 | 1392 | 1393 | 1394 | 1395 | 1396 | 1397 |

| 干支 Ganzhi | 戊辰 | 己巳 | 庚午 | 辛未 | 壬申 | 癸酉 | 甲戌 | 乙亥 | 丙子 | 丁丑 |

| 洪武 Hongwu | 31st year | |||||||||

|

Western calendar |

1398 | |||||||||

| 干支 Ganzhi | 戊寅 | |||||||||

literature

- Edward L. Dreyer: Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405-1433 . Pearson Education, New York 2007, ISBN 0-321-08443-8

- Frederick W. Mote: Imperial China 900–1800 . Harvard, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 0-674-44515-5

Web links

- Literature by and about Hongwu in the catalog of the German National Library

- Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum (English)

- Xiaoling Mausoleum of Hongwu near Nanjing

Individual evidence

- ↑ History of mankind. New chances. zdf info 2013

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Toghan Timur |

Emperor of China 1368–1398 |

Jianwen |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hongwu |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Zhu Yuanzhang (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Founder of the Ming Dynasty |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 21, 1328 |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 24, 1398 |