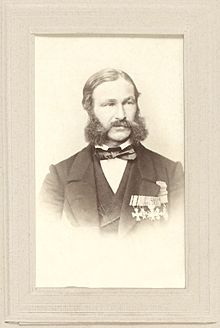

Heinrich Barth

Johann Heinrich Barth (* 16th February 1821 in Hamburg , † 25. November 1865 in Berlin ) was a German explorer and scientist ( historian , geographer , philologist ).

Heinrich Barth is not one of the best-known Africa researchers like Henry Morton Stanley and David Livingstone , which is primarily due to the fact that his travel book was not a bestseller. Barth addressed himself less to the general public than to the scientists, primarily the geographers and historians, and provided a detailed travel description and long excursions on the culture and history of the North and West African peoples, but no exciting adventures, although the expedition continued several times was at risk from life-threatening situations. In view of the limited contemporary interest in Africa in Germany, Barth's extensive work was only partially taken note of, and his far-sighted concept of an interdisciplinary African science was only taken up after 1950. Today he is not only considered a pioneer in Africa research, but also as one of the few explorers of the 19th century who met the Africans in a very impartial way and who were ready, for example, to enter into an intercultural dialogue with the representatives of African Islam .

Life

Youth and Studies

Heinrich Barth was born as the son of a wealthy butcher shop owner in Hamburg. As early as Easter 1831 he became a member of the Hamburg gymnastics association from 1816 , which Overweg also joined at the beginning of October 1837. He first attended a private school and moved to the renowned Johanneum , where he passed his Abitur in 1839. Even during his school days, he showed a pronounced talent for learning foreign languages and a great interest in antiquity. It is doubtful whether he learned Arabic, how to read from time to time, during his school days. Presumably he only acquired this language skills later, before his trip along the North African and Near Eastern coasts.

He then enrolled at the University of Berlin , where he took the main subjects Philology and Geography , but also attended lectures and seminars in German , history and law . His main interests were archeology and trade history. After a study trip that took him to Sicily , he received his doctorate in 1844 from the famous classical philologist August Boeckh with a doctoral thesis on the ancient history of trade in the eastern Mediterranean . The second reviewer of the dissertation was the founder of modern geography, Carl Ritter . Three years later, after a study trip through North Africa and the Middle East, he completed his habilitation for geography (including the history of geography) at the University of Berlin with a thesis on the Mediterranean basin in antiquity and became a private lecturer . In view of the revolutionary events of 1848, which Barth hardly noticed, only a few listeners came to his lectures and seminars. In addition, the lecturer was hardly able to present his subject matter in a gripping and structured manner. In view of the restrictive employment policy of the Prussian state, there was no opportunity for Barth to be appointed full professor for the foreseeable future. So he took it when he was offered participation in a British expedition. An unhappy love affair, which is sometimes mentioned in the biographical literature, is not documented in terms of sources and is unlikely to have been the decisive factor in Barth's decision. The expedition represented a calculable risk, as the route to Lake Chad had already been used by Europeans and had proven to be relatively safe: the risk of contracting malaria appeared to be low, and the peoples living there - mainly Tuaregs and Kanuri - had always been friendly to strangers.

At the same time, Barth was an excellent linguist and spoke fluent English , French , Spanish , Italian , Turkish and Arabic , as well as learning several African languages . During his trip to Africa, he made it his maxim to be able to communicate with the people he met in their own language, if possible. He mastered several dialects of Tamaschaq , the Tuareg language , the Moorish- Arabic dialects of northwest Africa, the Hausa , the Fulfulde and the Kanuri .

Brief overview of the two trips to Africa

Barth made his first trip to Africa from 1845 to 1847 along the Mediterranean coast of Tunisia and Libya and to Malta . He was primarily interested in the archaeological traces of antiquity (Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans) and not yet in the peoples of Inner Africa and their history and culture. In the border area between what is now Libya and Egypt, Barth was the victim of an attack in which he lost part of his diaries and, above all, his Daguerre photo camera. The report on this trip, which was primarily devoted to the importance of North Africa in ancient cultural and commercial history, was recognized as a habilitation thesis at Berlin University in 1847.

In 1849, the British government commissioned the missionary and abolitionist James Richardson with an expedition through the Sahara from Tripoli to Lake Chad . Since Richardson had no previous scientific training, Barth was placed as a companion on the British side through the mediation of the Prussian ambassador in London, Baron Christian Karl Josias von Bunsen . In addition, the astronomer and geologist Adolf Overweg was hired. Through this trip, which was probably the most important and best-equipped expedition to Africa, Barth achieved world fame, if only for a few years.

This journey lasted six years for Barth; his companions Richardson and Overweg died in 1851 (in what is now northern Nigeria ) and 1852 (on Lake Chad ). Barth was then appointed by the British government to lead the expedition. He explored the areas south of Lake Chad and the course of the Benue (tributary of the Niger ). Then he advanced to the famous trading city of Timbuktu and then returned to the starting point Tripoli. From there he traveled to London . On the way back from Timbuktu, he met Eduard Vogel , who had followed Barth, as he was considered missing. However, the two separated very soon. In total, Barth covered almost 20,000 km on the entire trip.

Barth's great journey through North and West Africa (1849–1855)

prehistory

After an initial expedition to the northern Tuareg in Tassili n'Ajjer , the missionary James Richardson had gained the impression that it was possible to stop the slave trade through the Sahara by intensifying the Trans- Saharan trade. The export of non-human goods from Sudan should be encouraged, and the European finished products coveted in Inner Africa should only be exchanged for export products of the type mentioned. To this end, Richardson wanted to conclude appropriate agreements with the rulers of Bornu and Sokoto . The Tuareg as the bearers of the Trans-Saharan trade should be won over as allies for the abolition of the slave trade. It was therefore planned to conclude contracts with their leaders that guaranteed the nomads protection from the French attacks in the direction of the Sahara. In 1849 the missionary was entrusted by the British government with the direction of a large-scale expedition aimed at finding out more about the great trade routes from the oases of the Sahara to the cities on the southern edge of the desert . The expedition was financed by the British government and the Royal Geographical Society , because in these circles it was hoped not only an expansion of geographical knowledge, but also direct access to the trade goods of inner Africa and at the same time an increase in the export of industrial finished products.

Richardson, who himself had no previous scientific training, wanted to make his expedition as international as possible, and when Prussian authorities suggested the private lecturer Barth, who had already gained experience in exploring the Middle East and North Africa, Richardson asked him to to participate in the expedition. He seemed an ideal candidate, especially because of his language skills, and enthusiastically agreed to Richardson's request. In the short term, his participation was in jeopardy because Barth's family did not want to raise the necessary financial contribution. The third member of the expedition was the young German astronomer and geologist Adolf Overweg.

Journey through the Sahara

The expedition left Tripoli (today's capital of Libya ) in March 1850 to cross the Sahara. First they had to overcome the waterless Hammada al-Hamra before they reached Murzuk in Fessan in May 1850 . It was not until June 13th that we continued over the high plateau of Messak Settafet and past the Akkakus Mountains to Ghat . After a short stay in Ghat, the expedition traveled over the foothills of the Tassili n'Ajjer and the Ahaggar Mountains to Tintellust in the Aïr Mountains, which they reached on September 4th.

The expedition was well organized. She had ample equipment, including a large wooden boat designed to explore Lake Chad. Barth was particularly well prepared scientifically, while Richardson already had desert experience and was very familiar with the wasteland and its dangers. Moreover, he had already made friends with the leaders of the Tuareg, which made the expedition's progress easier. However, the two men soon seem to have developed a personal dislike for each other, which led to the expedition being divided into two national groups, which even spent the night in two different camps.

On the high plateau of the Messak Settafet , Barth discovered some pictures that were carved into the rocks. The archaeologically interested researcher was the first scientist to recognize that the rock carvings would one day be an important source for the reconstruction of earlier cultural epochs, even though his locally formulated interpretations and, above all, the dating no longer correspond to the state of research today.

Shortly before they reached Ghat, they passed the Idinen mountain range . Barth decided to research this alone because he suspected there were remains of a prehistoric or ancient culture, possibly traces of the Garamanten people . Although he reached the ridge, he was exhausted and thirsty because he had used up all his water supply. He later got lost and passed out. When he finally woke up, he drank his own blood to stay conscious. He was then saved and led back to the expedition by a Targi who had the courage to risk his life for a Christian.

The passage through the mountains was very difficult and exhausting for the expedition, as they were also attacked by looters and later also further problems arose with the native Tuareg, as they saw the foreigners as a threat to their monopoly on the Trans-Saharan trade. Trade with Sudan was an important livelihood for the Saharan people. Another factor that made the journey much more difficult was the fear of the local population about a European conquest. After the occupation of Algiers in 1830 and the suppression of the resistance organized by Abd el-Kader in 1847, the French extended their influence to the northern oases of the Sahara, and evidence accumulated that the goal of this expansion was Lake Chad or Niger should be.

The trips in Sudan

From the Aïr , a mountain range in present-day Niger , the group traveled south to Agadez (present-day Niger), one of the major trading cities on the edge of the Sahara. Barth described the city as in decline, the population of which had shrunk from 50,000 to 7,000 as prosperity had plummeted in the mid-19th century.

Now the expedition members decided to split up the group. Richardson wanted to travel directly to Lake Chad with his part of the group, the two Germans wanted to find a western route to Lake Chad. Shortly afterwards, Barth split his group again and went alone to the cities of Katsina and Kano (today's Nigeria). The three men, Richardson, Barth, and Overweg, had agreed to meet in Kukawa in April 1851 , but Richardson had died of a fever three weeks earlier .

In Kuka (wa) Barth discovered the girgam , the royal chronicle of the kingdom of Kanem-Bornu , which he excerpted, with which he was able to insert another important stone into his mosaic of African history.

Overweg was the last to reach Lake Chad. But when he finally got there in May 1851, he was very exhausted and had a fever. Barth now explored the area south and east of Lake Chad and also the course of the Benue , a tributary of the Niger, and when Overweg was healthy again, he explored the lake himself with the help of the boat that the group had taken. The research lasted about 15 months. When the British government learned that Richardson had died, Barth was appointed the new leader of the expedition. Since the way to the east in the direction of the Nile was blocked, the two survivors decided to travel west, in the direction of Timbuktu (now Mali ), but Overweg died of malaria beforehand .

After the research on and around Lake Chad, Barth, now the only researcher in the group, traveled to the Kingdom of Kanem-Bornu (around Lake Chad). He was forced to take part in a campaign that degenerated into an organized slave hunt. Barth's description of the atrocities committed by Africans against Africans is one of the most shocking representations in classical African literature. When he returned to Kukawa, he had been traveling from Tripoli for about 32 months and knew that the journey to Timbuktu would take over a year. But Barth was convinced that he could achieve this goal.

Stay in Timbuktu

On the last part of his journey along the Niger, Barth was forced to pretend to be a Turkish Muslim who had come from Egypt to bring valuable books from Mecca to Timbuktu's chief Koran scholar , the Kunta Sheikh Sidi Ahmad al-Baqqai . The background to the xenophobia was the memory of the trip through the Schotten Mungo Park , which had been shot when it was cruising the Niger in the winter of 1805–1806 for fear of an attack on anyone approaching the bank.

Barth reached Timbuktu on September 7, 1853. He found the city more affluent than René-Auguste Caillié , a French African explorer, had described it 25 years earlier. However, this city has never again become the trading center for the Sahara as it had been until the end of the 16th century. For Barth it was a great satisfaction to be able to confirm Caillié's information about the actual state of Timbuktu, which had been questioned for a long time - especially by the British side. On the day of his arrival he wrote corresponding letters to the presidents of the geographic societies in London and Paris.

Barth's arrival in Timbuktu coincided with news of French conquests in southern Algeria and Senegal . The population received him with great suspicion, and the powerful Fulani ruler of Macina in present-day Mali demanded his extradition. But the researcher was protected by the spiritual leader of the city, Sidi Ahmad al-Baqqai. The sheikh even prepared a kind of fatwa , a legal opinion in which he categorically denied the Fulbe ruler the right to persecute a Christian who had come as a friend. Under the protection of this most famous Koran scholar in West Africa, Barth was able to pursue his historical research and view and partially excerpt documents about the medieval and early modern empires of West Africa ( Mali and Songhai ). At the same time, he had long theological conversations with al-Baqqai, in which both men discussed the similarities between Islam and Christianity and recognized the great similarities between the religions. At times, Barth had to leave the city because of the stalking by the Fulbe and place himself under the protection of the Tuareg, who recognized al-Baqqai as their religious leader.

Barth's return to Europe

In the spring of 1854 Barth left Timbuktu for good and traveled back to Lake Chad. The route took him to Gao , among other places , where he visited and drew the graves of the Songhai rulers. On the way east he learned that an expedition led by the German Eduard Vogel had arrived at Lake Chad; the British government had sent this expedition to look for Barth, who was considered missing or dead, and to continue his research if necessary. When the groups met, it was decided that Barth should return to Kuka (wa) (present-day Nigeria) and Vogel should travel to Zinder (present-day Niger). From there he wanted to try to travel the course of the Niger, which has not yet been explored by Europeans, and from there possibly penetrate the Nile . In this venture, however, Vogel was murdered in the Wadai Empire (in present-day Chad). Barth traveled from Kuka via Murzuk back to Tripoli (arrival in Tripoli on August 28, 1855), taking with him two British soldiers who had accompanied Vogel and had fallen out with him. He was accompanied by two slaves from Sudan, Abbega and Durugu, who had been ransomed by Adolf Overweg and who were supposed to help him with the composition of his linguistic works. Via Marseille and Paris he traveled first to Hamburg, then to London, where he wanted to settle permanently and pursue his research. In 1854 Barth was elected a member of the Leopoldina .

Barth's life after the great trip to Africa

Barth first settled in London, where he simultaneously wrote the German and English versions of his 3,500-page travel book. Both editions are largely identical, but differ in some essential points. At the same time he tried to persuade the British government to become politically active in the Sahara and the Sahel in order to prevent the violent expansion of the French colonial empire into the Tuareg country and Timbuktu, but met with no interest.

In addition, the researcher faced massive attacks on the part of the mission societies and the anti-slavery movement , who accused him of having participated in slave hunts , although the description provided by Barth offered first-rate arguments in the fight for the abolition of slavery. Furthermore, the charge was made that he had also brought slaves with him to England. In fact, he had taken two ransomed Africans with him to London to help him write his linguistic works. This was not unusual, other travelers, missionaries, captains etc. also brought black servants with them to England. The background to the campaign staged against Heinrich Barth was not least to be found in the fact that, as a foreigner, he threatened to overtake the popular missionary and researcher David Livingstone . But even Barth's positive assessment of Islam did not fit into the British view of the world.

In 1858 Barth left London and went back to Berlin, hoping that he would be given the professorship of his retired teacher Carl Ritter in geography, which did not happen. From 1858 to 1862 Barth traveled to Asia Minor , Greece and Bulgaria as well as Spain , Italy and the Alps . As the successor to Carl Ritter, he was President of the “ Society for Geography in Berlin” and sponsored a number of young African researchers such as the French Henri Duveyrier , who followed up on Barth's research on the Tuareg in the northern Sahara. At times, in view of the difficulties in finding permanent employment, Barth tried to send him to Constantinople as consul , but was not considered because he was considered an undiplomatic character. In 1863 he was made an associate professor at the University of Berlin, which means that he held lectures and seminars free of charge. However, he was denied a full professorship, so that he had to live primarily on the annuity granted to him by the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV . His travel work was only sold very slowly because of its high scientific nature, its size (3,500 pages) and the resulting high price. A two-volume popular edition was also not a best seller.

Heinrich Barth died in 1865 of a gastric rupture , possibly the aftermath of a gunshot wound that he suffered in Libya on his Mediterranean trip in 1847. He was buried in Berlin in the cemetery III of the Jerusalem and New Churches in front of the Hallesches Tor . The grave site is marked by a small recumbent tombstone.

Performance and aftermath

Preliminary remark

Despite the innumerable difficulties and also the deaths of Richardson and Overweg, the expedition was a great success, which was particularly credited to Barth. He had gathered a huge amount of information about North Africa, so that his patron and sponsor Alexander von Humboldt could say that Barth had opened up a new continent for European science. He was also the first researcher to create maps of large areas of Africa (Sahara and Sahel), although Alexander von Humboldt criticized Barth's geographical measurements as not being very professional. From the point of view of today's science, Barth's main merit lies in researching African cultures, which the researcher was the first European to describe comprehensively and largely without prejudice. It is precisely in this respect that Barth's research achievements should, in retrospect, be rated higher than that of such well-known travelers as Henry Morton Stanley or David Livingstone. Her works were much more suited to European public tastes, as they portrayed the white man, the messenger of civilization, in his constant struggle with wild animals and wild people, while Barth provided a 3,500-page scientific presentation of cultures whose existence the European science had hardly known anything up to now and, due to narrow-mindedness partly motivated by race ideology, still wanted to know nothing. Barth's travel description was interrupted on various occasions by extensive excursions on ethnological and historical topics, such as the culture of the Tuareg, the history of Agades or Songhai, and each of these excursions, which were only supplemented and updated after 1900 in view of the rapidly advancing exploration of the colonies, had for the quality of an academic dissertation, as the author also used earlier literature - up to ancient authors such as Herodotus and Pliny - for comparison. The remarks on the Tuareg of the Tassili n'Ajjer, the Aïr Mountains or the area around Timbuktu are still indispensable for today's ethnography.

Barth had made his five-year trip to Africa almost without firing a single shot in defense. While he was considered harsh and undiplomatic in Europe, he made numerous friends in the Sahara and Sudan. In this way, later researchers who came up to the end of the 19th century - i. H. until the colonial occupation by France - stayed with the Tuareg and pretended to be Barth's son or nephew, traveling relatively safely, for example Oskar Lenz , who visited Timbuktu in 1879 and was greeted by friends of his alleged father. However, it must be emphasized that Barth was fortunate to have a competent and absolutely loyal companion in the caravan leader Mohammad from the Libyan oasis of Qatrun. Mohammad al-Qatruni later also served Gerhard Rohlfs and Gustav Nachtigal .

The failure of Barth's diplomatic activities

In England, Barth fell on deaf ears with his demand for the ratification of the trade and protection treaties he had concluded with the Africans. A delegation from the Grand Council of Timbuktu, who wanted to travel to London at the researcher's suggestion, was detained in Tripoli under degrading circumstances and then sent back to Sudan under mockery of the British press. British foreign policy had turned its attention to the Sahara while Barth was still traveling in Africa. An expedition under the direction of the doctor Balfour Baikie, sent out almost at the same time, had opened up the route from the Niger Delta in what is now Nigeria to Inner Africa and provided evidence that this route was safe for Europeans if they used quinine to protect themselves from the common febrile diseases. This made the longer Sahara route, on which there was no threat of epidemics, of no interest. After the end of the Anglo-French conflict, i. H. In the years after the Crimean War , in which both countries had been allies, British foreign policy left the Sahara to the French and instead claimed control of large parts of the West African coast, particularly the Niger Delta. The French side agreed with such a division of the zones of interest, since the aim of the unification of the colonies in Algeria and Senegal was pursued in Paris, and the area between these two possessions was the land of the Tuareg, with whom Barth had also concluded treaties. Barth's advocacy for the African peoples and his demand for the ratification of the treaties were finally seen as a nuisance in the Foreign Office , and he was told that he was politically naive and should take note of the change of course in British Africa policy.

Timbuktu no longer played a prominent role in the awareness of the British public, as the city apparently no longer promised to play a major role in the export economy. Barth's discoveries in history were not fascinating enough in view of the question of the sources of the Nile, which was hotly debated in the press. The fact that Barth was a foreigner in London and could possibly compete with the extremely popular David Livingstone should not be underestimated either. The missionary societies and the “Anti-Slavery Society” raised the mood against him, which was certainly also due to his emphatically positive attitude towards Islam. Barth was named "Companion of the Order of the Bath " - an exceptional honor for a non-British - but he was not presented to Queen Victoria as part of this honor , in contrast to the Hungarian Arminius Vambéry , who is in Central Asia Had traveled areas to which the British colonial politicians turned their attention. In Germany, on the other hand, Barth was resented for having traveled on behalf of the British, at a time when British foreign policy had prevented the unification of Germany longed for by many liberal intellectuals (1849).

Striving for an academic position

In addition, there were more academic problems, which ultimately led to the fact that he was denied the full professorship at the University of Berlin, although he had all the qualifications for it. But his persistent advocacy of the equality of Africans, his assertion that Africa is by no means a continent devoid of history, and probably also his outmoded, positive image of Islam made him suspicious of the established professors. Leopold von Ranke , Germany's best-known historian and professor in Berlin, wrote in a report that Barth was a daring adventurer, but not a scholar to be taken seriously. Ranke himself had denied the Africans any ability to have history, which was a devastating judgment in the 19th century, when a people's assumed ability to develop and history was viewed as an important criterion for their ranking within humanity. With this, Barth's attempt to establish research into African history in the academic field, albeit through the detour via historical geography, finally failed.

At times an appointment to the University of Jena was under discussion, but Barth does not seem to have been interested. It was not until 1863 that he was appointed associate professor of geography at the Berlin University, which in practice meant that he continued to teach without a fixed salary and had to make a living from the annuity that King Friedrich Wilhelm IV had suspended. Apparently with a view to the rejection of his image of Africa in academic circles, he held courses that were thematically within the generally accepted framework and in some cases were not much more than a slightly updated new edition of Carl Ritter's lectures. It seems that Barth tried to be able to succeed him after all by following the conceptions of his academic teacher, which was clearly recognizable for the faculty.

Barth, Africa and the Africans

Whether Heinrich Barth in 1849, when he accepted the invitation to participate in the “Central African Mission”, did so out of interest in Inner Africa or primarily hoped to take part in a spectacular research project and then the longed-for professorship for geography at the University of Berlin obtaining is controversial. But one can at least assume that on his first trip along the North African coast he realized that the Mediterranean world had been in constant contact with Inner Africa, and the archaeologist and archaeologist Barth was certainly keen to trace traces of these commercial and cultural relationships the Sahara or even south of it.

Barth's interest in African cultures developed rapidly and to an unusual extent for 19th-century European travelers. The researcher was ready to recognize Africans as his own, did not appear as an arrogant white man who could only converse with people through interpreters, but learned the languages of Central Africa to such a degree that he was later able to use them scientifically analyze. The ethnologist Gerd Spittler ( University of Bayreuth ) describes Barth as one of the most important precursors of ethnological field research , which in the history of science only began with Bronisław Malinowski's book on the Trobriand islanders (1922).

Even if Barth occasionally echoes the typical conviction of the Europeans that their culture is superior to all others, he used the term " nation ", which is highly emotional for Germans, for the peoples of Africa and thus put them on a par with the Europeans. If the conclusions that he drew from his research results are largely out of date or even refuted today, it can be said that he considered the languages and cultures of Africans to be worthy of scientific investigation. In this context, the fact that Barth took no notice of the theories about the biological inferiority of Africans, which were defended at the time, because for him cultural ability was not determined by belonging to a certain race, but rather that it was given to all people equally It was an ability which, through contact with other cultures, developed further in a dialectical sense. He was completely in the tradition of his teacher Carl Ritter and in stark contrast to philosophers of history such as Hegel , historians such as Ranke and racial ideologues such as Karl Andree , the editor of the popular magazine Globus .

Exploring the history of Africa

While crossing the northern Sahara, Barth came across remnants of the ancient history of North Africa, which he knew very well from the writings of Greek and Roman authors. He had also studied the reports of the Arab travelers. In this respect, his concept of history moved along the lines of academic tradition, which placed the study of written sources in the foreground. The discovery of the rock carvings meant a break in his understanding of history for him, because for the first time he recognized that the classic source concept failed here, unless one wanted to deny the historicity of the Africans, as the leading historians and philosophers in Europe did. It is therefore not surprising that Leopold v. Ranke was one of those reviewers at Berlin University who opposed applications to grant Barth a professorship or to accept him as a full member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences , on the grounds that the candidate had done nothing of value for historical research, but rather had rather a "bold traveler", which in the parlance of the time should not be seen as a compliment.

On the one hand, Barth recognized that Africans did not just have a past, but a history that they themselves had shaped. This view alone represented a massive break with the European view of history, because both Hegel and the cultural historian Gustav Friedrich Klemm had depicted the Africans as a passive race, which was never the subject, but only the object of history and was only activated by an external impulse could be. Barth attested the Africans a deliberately designed history that was in conflict and contact with the world outside of Africa, received impulses from there, but also gave impetus to the outside world. This realization led him to make the heretical adage that world history could not be written until African history was fully explored. It cannot be denied that Barth considered the Africans historically backward. He liked to compare the kingdoms of Sudan with the European Middle Ages, but this in no way ruled out that they would develop further if this process were not hindered by armed events and false influence from outside. In doing so, he was entirely in line with the philosophers of history of his time, including Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels , who also postulated a rigid sequence of historical forms of development and at the same time thought much more European-centric and one-dimensional than Barth, who saw Islam as a force that promoted culture and European influences was very critical in Africa. In contrast to most of his contemporaries, who saw a causal connection between the alleged position of a people in the racial hierarchy on the one hand and their cultural and historical abilities on the other, Barth rejected any biological explanatory model and thus attested the same abilities and the same development opportunities to all human races.

Heinrich Barth broke away from the traditional methodology of academically established historical studies and created, at least in its basic features, a set of instruments that made it possible to research the history of non-European cultures. Established methods such as the evaluation of written sources (such as the Sudanese chronicles) were no longer the focus. Linguistics, the comparison of vocabulary and grammatical structures in order to determine migration and cultural contacts, should also be used. The interpretation of rites and customs also played an important role. It should be emphasized that the rock paintings would one day be an indispensable source for research into prehistory and early history (including climatic history). Many of Barth's interpretations have turned out to be wrong, but the criticism that has recently been leveled at certain aspects of his methodology and certain conclusions is short-sighted because it ignores the fact that Barth was forced to complete his scientific research within a short period of time and often under difficult conditions such as in Timbuktu.

Barth and African Linguistics

His services to African linguistics were also disputed in corresponding reports, which was less due to the quality of his research than to the fact that he considered the languages of Africans to be worthy of research and thus on a par with the Indo-European languages. The rejection by the established linguists had also felt other researchers, such as Wilhelm Bleek , who was forced to accept a position in South Africa after completing his doctorate on the Bantu languages, as there was no place in the academic field in Germany for an outsider like him was. A turn to research into African languages did not take place until the end of the 19th century, but not for the sake of scientific investigation, but for the purpose of making them useful in the context of an efficient colonial policy. In practice, this meant that prospective colonial officials and officers learned the African language in order to be able to communicate with the population in the colonies, but linguistic research, e.g. B. on the history of language, were not provided, but could only be pursued by the lecturers as a hobby outside of the actual teaching.

Barth's Central African Vocabularies , which are far more than mere lists of words, are regarded as the beginning of comparative African studies, although many of the conclusions drawn by the researcher are no longer recognized as valid today - in view of a large number of special linguistic investigations. His methodical approach, however, is still described as exemplary by leading Africanists.

Barth and Islam

It can be assumed that Barth also failed because of his completely out of date advocacy for Islam. In the public consciousness this religion was regarded as hostile to civilization and its bearers as fanatical and xenophobic. Barth had wisely made it a principle to respect the habits and customs of Islamic life, as long as these were not in stark contrast to his ideas of humanity. He had experienced xenophobic behavior anyway, but he was objective enough to look for the reasons for it. He found it in the low level of education of many African Muslims, in the fear of foreigners in general and of the advance of the French in particular. On the other hand, he repeatedly met educated Muslims such as the Marabout Sidi Uthman among the Tuareg, the blind Fulani scholar Faki Ssambo or the spiritual and political leader of Timbuktu, Sidi Ahmad al-Baqqai. With these men he was able to have a peaceful intercultural dialogue and discuss religion, history and philosophy, and it was from them that he wrote some of the few very personal, almost touchingly phrased accounts of individuals with whom he had maintained closer contact on his journey.

Barth must be viewed as a very good and above all impartial expert on Islam, so that he was able to discuss the nuances of theology with highly educated Koran scholars in Sokoto or Timbuktu. Barth probably overestimated the role of Islam in the formation of the old West African empires in view of the chronicles available to him, but it was precisely this assessment that led him to oppose the Christian missions and their claim that they alone could bring Africa to civilization in a polemical way . A religion like Islam, which had brought West Africa to such a high level of culture in the Middle Ages, could, in his view, not possibly be hostile to civilization. In several letters, but also in published articles, he called for an intellectual balance to be sought with Islam and for this religion to take precedence in the further development of Africa. This demand was by no means based on the belief, which was more common towards the end of the 19th century, that Islam, as an inferior religion, was better suited to a race that was not capable of development. Rather, for Barth it was a proven fact that the Africans were intellectually equal to the Europeans and that Islam was equal to Christianity in theological and cultural-historical terms. In one of his last articles he put forward the utopian idea that Europeans and Muslims should found a Christian-Islamic academy in West Africa, in which the opportunity for a rapprochement and a balance between the two religions could be created. With such a view, however, he had to provoke, for example, the opposition of the influential “Berlin Mission Society”, active in Africa, whose connections reached into the highest social circles.

The more recent criticism that Barth was not African-friendly, but only Islam-friendly, is one-sided, as Barth traveled almost exclusively in Islamic areas and only had the opportunity to visit non-Muslim peoples in exceptional situations (e.g. in the wake of a slave hunt). But his remarks show that he was generally open to the Africans and free of prejudice. The works in which this criticism is expressed are based on an inadequate source base and ignore Barth's journal articles and correspondence. The Barth critics also do not take sufficient account of contemporary discourses; H. the framework given by established science in which Barth moved or had to move intellectually and structurally and which he often deliberately broke through.

The Mediterranean Project

It is wrong to see Barth exclusively as an African scientist. During his student days he had already developed a great interest in the history of the Mediterranean and its role in the development and communication of cultures. He had deepened this knowledge during his major study trip between 1844 and 1847 and laid down the main features in his habilitation thesis. In his travel book, too, he repeatedly referred to the possibilities of a cultural exchange between the Mediterranean and Inner Africa. In a lecture from 1860 he emphasized that the Mediterranean region had always been a pivotal point in cultural history, where different cultures had collided, mixed with one another and radiated in different directions, whereby the racial affiliation of the individual peoples played no role for him . Barth saw no barrier between cultures or religions in the Mediterranean, but a region of intensive exchange, although he did not deny that the contact had not always been peaceful. For him, black Africa had therefore never stood in isolation alongside general world history, but had always been an integral part. Exchange through trade was at the fore in Barth's concept of cultural contact. The trips that Barth undertook in the last years of his life in Turkey and the Balkans (including the first to climb Mount Olympus ) served to underpin this theory, which, given his early death, has only survived in fragments. However, these fragments show that Barth, with his new view of the Mediterranean as a cultural and historical unit, already referred to the history of the 20th century. He anticipated the conception that the famous French historian Fernand Braudel (1902–1985) almost 100 years later in his famous work on the Mediterranean in the age of Philip II . resigned.

Afterlife in the colonial and post-colonial ages

In keeping with the bourgeois ideology of progress in the 19th century, Barth welcomed the opening up of Africa by the Europeans, with an eye on the intensification of trade in both directions. The introduction of the so-called “legitimate trade” was intended to prevent the slave trade - at a time when not only American ideologues but also German scholars, citing the alleged racial inferiority of Africans, made slavery an economically necessary and even morally justifiable institution defended. For Barth, African history was not doomed to standstill, but was tied into general human progress and destined to go through the same stages of development. However, Barth distanced himself from this unilinear view of history at the latest when he was reflecting on his research results and developed a sometimes violent criticism of the European intervention in Africa. The first target of attack were the missions, which he accused of the systematic destruction of traditional cultures and values. Barth designed an Islamic Africa as a vision for the future, because for him Islam represented a religion capable of culturally speaking. He also realized that he had been abused by the British side when he concluded friendship treaties with African leaders in good faith. The moment the British lost interest in the Sahara, France was able to use military means to seize supremacy. In view of this knowledge, Barth wrote that he could well imagine riding against the colonial conquerors with a Muslim liberation army led by Sheikh al-Baqqai. This colonial criticism, probably unique in the 19th century, was systematically suppressed by his biographers.

Soon after his death, Barth was forgotten. In the colonial age from 1884 onwards, with his unconventional ideas and his critical attitude towards the European reach into Africa, he proved to be useless. Other travelers such as Gustav Nachtigal , Gerhard Rohlfs , Carl Peters and Hermann von Wissmann dominated the headlines because they had acquired colonies for the German Empire and secured them militarily, while with the exception of the kingdoms of Mandara and Logone none of the areas visited by Barth was a German " protected area " had become. During National Socialism he was even accused of “ racial disgrace ”. In the Cold War era , the researcher finally came to the bone of contention between the FRG and the GDR, as the Federal Republic's foreign policy portrayed Barth as the forerunner of the new German Africa policy, while the GDR, which fought for recognition by the young African states, did fought back incorrect claim that Barth was a bad imperialist and racist and thus a real forerunner of "West German neo-imperialism". Both perspectives were dictated by politics and in no way did justice to Barth's importance.

Barth as a forerunner of interdisciplinary African studies

Heinrich Barth was not rediscovered as an important and trend-setting scientist until the 1960s, primarily in Great Britain and Africa. One of the first historians to recognize Barth's work was Albert Adu Boahen , a Ghanaian who was the first African to do a PhD in history at the London School of Oriental and African Studies . He saw Barth as an opponent of colonial conquest and, in his doctoral thesis, sharply criticized the British Africa policy of the 19th century. The rediscovery of the scientist Barth was initiated in the Federal Republic by the geographer Heinrich Schiffers and the writers Rolf Italiaander and Herbert Kaufmann . In the past few years Heinrich Barth has been the subject of documentaries several times, in which his role as the discoverer of the rock art and his stay in Timbuktu was highlighted. This happened several times in a simplistic, journalistic manner and without thorough research, so that Barth appeared as one adventurer among many, while his importance for the development of modern African science was suppressed because the authors were not interested or because they were of the opinion that it was relevant Information for readers or television viewers is insignificant.

Africanists value Barth above all for the interdisciplinary approach - the connection between geography, archeology, history, linguistics and ethnology - and continue to work in this sense today, even if it is no longer possible for a single scientist to survey all subject areas. In place of the romantic polymath of the caliber of Alexander von Humboldt and Heinrich Barth teams entered who work in interdisciplinary projects on issues that Barth has raised the first researcher. The employees of the “Sokoto Project” at York University in Ontario, Canada (led by Alexander S. Kanya-Forstner and Paul Lovejoy) expressly see their work as a continuation of the approaches given by Heinrich Barth with the possibilities of the 20th and 21st centuries .

Memory of Barth

The "Heinrich Barth Institute" has existed at the University of Cologne since 1988, which is primarily dedicated to research into early African history in connection with the history of the climate and, above all, in Barth's spirit, records and evaluates African rock art.

In Agadez , a small museum has been set up in the house in which Heinrich Barth lived from October 9th to 30th, 1850. A plaque commemorates the first European to step into Agadez.

In Kano , the house in which Barth lived is now a small museum.

There are Heinrich-Barth-Strasse in Hamburg, Saarbrücken and Euskirchen.

By resolution of the Berlin Senate , Heinrich Barth's final resting place in Cemetery III has been dedicated to the Jerusalem and New Churches as an honorary grave for the State of Berlin since 1970 . The dedication was extended in 1997 by the now usual period of twenty years.

The Barth Bjerge in East Greenland were named after Heinrich Barth by the Second German North Pole Expedition in 1869/70.

Fonts (selection)

- Corinthiorum commercii et mercaturae historiae particulaer . Dissertation Berlin 1844 (new edition in German [contributions to the history of trade and trade in Corinth] and English translation. Africa Explorata. Monographs on early exploration of Africa 2. Heinrich Barth Institute, Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-927688-21-5 ) .

- Migrations through the coastal lands of the Mediterranean Sea carried out in 1845, 1846 and 1847 . Berlin 1849 (first and only volume of his habilitation thesis from 1847).

-

Travels and discoveries in North and Central Africa . 5 volumes. Gotha 1855-1858. (Digitized: Volume 1 in the Google Book Search, Volume 2 - Internet Archive , Volume 3 - Internet Archive , Volume 4 (BSB-MDZ) , Volume 5 - Internet Archive ).

- (Reprint Saarbrücken 2005: Volume 1 ISBN 3-927688-24-X , Volume 2: ISBN 3-927688-26-6 , Volume 3: ISBN 3-927688-27-4 , Volume 4: ISBN 3-927688-28- 2 , Volume 5: ISBN 3-927688-29-0 ; short version as: In the saddle through North and Central Africa. 1849–1855 . Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-86503-253-2 ).

- The basin of the Mediterranean in a natural and cultural-historical relationship . Hamburg 1860.

- Journey from Trebizond through the northern half of Asia Minor to Scutari in autumn 1858 . Gotha 1860 (new edition: Barth's journey through Asia Minor. An annotated travel report . H. Köhler (Ed.), Gotha 2000, ISBN 3-623-00357-3 ).

- Journey through the interior of European Turkey from Rutschuk via Philippopel, Rilo (Monastir), Bitolia u. Mount Olympus from Thessaly to Salonika in autumn 1862 . Berlin 1864. (digitized: archive.org ). First published in the Zeitschrift für Allgemeine Erdkunde , NF 15 (1863), pp. 301–358, 457–538; 16 (1864), pp. 117-208

- Collection and processing of Central African vocabulary . 3 departments. Gotha 1862–1866.

- He opened up a part of the world for us. Unpublished letters and drawings by the great Africa explorer . Edited by Rolf Italiaander, Bad Kreuznach 1970.

English language editions:

- Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa: being a Journal of an Expedition undertaken under the Auspices of HBM's Government, in the Years 1849–1855… 5 volumes. London: Longmans, Green & Co 1857-1858.

- (US edition with fewer illustrations) 3 volumes. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1859 ( Volume 1 - Internet Archive , Volume 3 - Internet Archive ).

- Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa . 3 volumes. Edited by Anthony HM Kirk-Greene. Cass, London 1967 (edition in 3 volumes with full text, edited by the leading British Barth connoisseur).

literature

- Julius Löwenberg : Barth, Heinrich . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 2, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1875, p. 96.

- Albert Adu Boahen : Britain, the Sahara and the Western Sudan, 1788–1861 . Oxford 1964 (Still the most important scientific study on the early phase of Sahara research with a detailed chapter on Barth and his efforts in favor of the Africans).

- Hans-Heinrich Bass, From the Sahara to the shores of Lake Chad. In the footsteps of Heinrich Barth in Africa , in: Damals 3/1995, pp. 74–79.

- Yvonne Deck: Heinrich Barth in Africa - Dealing with the foreign. An analysis of his great travel work . Master's thesis, University of Konstanz 2006 ( full text )

- Mamadou Diawara, Paulo Farias and Gerd Spittler (eds.): Heinrich Barth et l'Afrique . Cologne 2006 (anthology with essays held on the occasion of a scientific conference in Timbuktu).

- Heinrich-Barth-Institut (Ed.): Ten pages of an Africa researcher . Cologne 2000.

- Dietmar Henze: Encyclopedia of the explorers and explorers of the earth. Volume 1. Graz 1975, keyword “Heinrich Barth”, pp. 175–183.

- Ernst Keienburg: The man whose name was Abd el Kerim. Heinrich Barth's research life in the desert and wilderness. Berlin 1961.

- Steve Kemper: A Labyrinth of Kingdoms - 10,000 Miles Through Islamic Africa . New York, London 2012.

- Peter Kremer: Literature by and about Heinrich Barth . In: Heinrich Barth: Corinthiorum commercii et mercaturae historiae particula. In German and English translation, Heinrich Barth Institute, Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-927688-21-5 , pp. 163-216 (complete bibliography of the literature up to around 2000).

- Peter Kremer: Africanus. Life and travels of the Africa explorer Heinrich Barth . Düren 2007.

- Christoph Marx: Heinrich Barth . In: Ders .: Peoples without writing and history. On the historical record of pre-colonial black Africa in German research of the 19th and early 20th centuries . Contributions to colonial and overseas history 43. Stuttgart 1988, pp. 9–39, ISBN 3-515-05173-2 ( rich in material, but without in-depth analysis of the failure of Barth's attempt to establish academic research into African history).

- Heinrich Schiffers (Ed.): Heinrich Barth. A researcher in Africa. Life - performance - effect . Wiesbaden 1967 (important collection of essays in which individual aspects of Barth's scientific work are examined from a more recent perspective).

- Heinrich Schiffers: The Great Journey. Dr. Heinrich Barth's research and adventure. Portrayed by Heinrich Schiffers. Wilhelm Köhler (undated [approx. 1955]), Minden (Westf.), 275 pp.

- Walther Schoenichen: Consecrated sites of the cosmopolitan city. Tombs of Berlin and what they tell. Berlin and Leipzig 1929 (1st edition Langensalza 1928).

- Gustav v. Schubert: Heinrich Barth. The pioneer in German Africa research . Leipzig 1898 (biography from the pen of Barth's brother-in-law, the basis of all later biographies).

- Klaus Schroeder: Barth, Heinrich. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 1, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1953, ISBN 3-428-00182-6 , p. 602 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Karl Rolf Seufert : The caravan of white men. Herder-Verlag, Freiburg / Breisgau 1961.

- Gerd Spittler : Heinrich Barth, un voyageur savant en Afrique. In: Diawara, Farias, Spittler: Heinrich Barth. Pp. 55-68.

Web links

- Heinrich Barth Institute for Archeology and Environmental History of Africa V.

- Literature by and about Heinrich Barth in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Heinrich Barth in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Timbuktu - fizzled out (article in the FAZ of 23 May 2004 about Heinrich Barth in Timbuktu)

- Bibliography on the history of Timbuktu and the research trips there ( Memento from February 12, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- Website of the "Heinrich Barth Society" in Cologne

- House where Barth lived in Timbuktu

- Digital version of journeys and discoveries in North and Central Africa from 1849 to 1855

Remarks

- ↑ As the date of birth, April 18th is also given on various occasions, but this seems to be a mistranslation of his date of birth, quoted in Latin mode, as it appears in the curriculum vitae in the dissertation. Barth states that on “14. Kalenden des M (ärz) ”to be born, but the composer read this as“ May ”.

- ^ Carl Heitmann: Timeline of the history of the Hamburg gymnastics club from 1816: 1816 - 1882. Herbst, Hamburg, 1883, p. 6. ( online )

- ↑ The best overview of the trips from a geographic-historical perspective is still provided by the article "Barth, Heinrich." In: Dietmar Henze: Enzyklopädie der Entdecker und Erforscher der Erde. Graz 1978, Volume 1, pp. 175-183. Barth's research on the human sciences (history, linguistics, ethnology) is only touched on in passing.

- ↑ See the corresponding chapter in AA Boahen: Britain, the Sahara and the Western Sudan 1788–1861. London 1964, pp. 181-212.

- ^ Heinrich Barth: Travels and discoveries in North and Central Africa . Gotha 1855–1858 (Reprint Saarbrücken 2005: Volume 1, ISBN 3-927688-24-X , p. 210 ff.)

- ↑ The most important passages of the fatwa are printed in AA Boahen: Britain, the Sahara and the Western Sudan. Annex IV., P. 251 f.

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Mende : Lexicon of Berlin burial places . Pharus-Plan, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-86514-206-1 , p. 239.

- ↑ See in detail AA Boahen: Britain, the Sahara and the Western Sudan. P. 213 ff .; and Ralph M. Prothero: Barth and the British. In: Heinrich Schiffers (Hrsg.): Heinrich Barth - a researcher in Africa. Wiesbaden 1967, pp. 164-183.

- ^ Spittler in M. Diawara, P. Farias and G. Spittler: Heinrich Barth et l'Afrique. Pp. 56-68.

- ^ Gerhard Engelmann: Heinrich Barth in Berlin. In: Heinrich Schiffers (Hrsg.): Heinrich Barth - a researcher in Africa. Wiesbaden 1967, pp. 108-147.

- ↑ See Pekka Masonen: The Negroland Revisited: Discovery and Invention of the Sudanese Middle Ages. Helsinki 2000, pp. 397-418. We must not overlook the fact that historians around the middle of the 19th century saw the Middle Ages as the most important epoch in German history and that Barth placed the West African kingdoms on the same level as the Hohenstaufen, for example. This is likely to have met with rejection from many of his German-national colleagues.

- ^ Article Neger, Negerstaaten. In: JC Bluntschli and K. Brater (Eds.): German State Dictionary. Volume 7, Stuttgart / Leipzig 1862, pp. 219-247, spec. P. 219 ff.

- ↑ Paulo Fernando de Moraes Farias: Barth, fondateur d'une lecture reductrice des chroniques de Tombouctou. In: D. Mamadou, P. Farias and G. Spittler (eds.): Heinrich Barth et l'Afrique. Cologne 2006, pp. 215-224.

- ^ The latest relations between the French in Senegal and Timbuktu , Zeitschrift für Allgemeine Gekunde NF 16 (1864), pp. 517-526.

- ↑ For example, the master's thesis by Yvonne Deck: Heinrich Barth in Africa - Dealing with the Stranger. Konstanz 2006 (see under literature).

- ↑ Barth: Reisen , III, 112-135, 232-257.

- ↑ See u. a. the polemics in Thea Büttner: Africa. History from the beginning to the present. Berlin (GDR) 1979, volume 1, p. 307 f.

- ↑ Adu Boahen, who died in 2006, was internationally regarded as the most prominent black African historian alongside Joseph Ki-Zerbo .

- ↑ Recent examples: Ulli Kulke : The great discoverers. Stuttgart 2006, pp. 163–174 (with serious errors in content), review

- ↑ The Timbuktu Scrolls ( Memento of the original of September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Broadcast on January 23, 2007 on 3sat

- ↑ Hans-Heinrich Bass: From the Sahara to the shores of Lake Chad. In the footsteps of Heinrich Barth in Africa. In: Damals , 3/1995, pp. 74–79.

- ↑ Honorary graves of the State of Berlin (as of November 2018) . (PDF, 413 kB) Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection, p. 3; accessed on March 27, 2019. Submission - for information - about the recognition and further preservation of graves of well-known and deserving personalities as honorary graves of Berlin . (PDF) Berlin House of Representatives, printed matter 13/2017 of September 12, 1997, section B); accessed on March 27, 2019.

- ↑ Østgrønlandske Stednavne - Fra den første kortlægning . (PDF; 9.54 MB) on the website of the Danish Arctic Institute (Danish)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Barth, Heinrich |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German Africa explorer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 16, 1821 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hamburg |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 25, 1865 |

| Place of death | Berlin |