Victoria (United Kingdom)

Victoria - born Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent - (* 24. May 1819 in Kensington Palace , London ; † 22. January 1901 in Osborne House , Isle of Wight ) was 1837-1901 Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland , from 1 May 1876 she was the first British monarch to also bear the title of Empress of India . She was the daughter of Edward Augustus, Duke of Kent and Strathearn , and Victoire von Sachsen-Coburg-Saalfeld.

With Victoria's accession to the throne on June 20, 1837 , the personal union between Great Britain and Hanover , which had existed since 1714, ended due to the Sali law in force in the Kingdom of Hanover , which excluded women from the line of succession . During the 63-year reign of Victoria, the British Empire reached the height of its political and economic power, the upper and middle classes experienced an unprecedented economic heyday ( Victorian era ). Characteristic of her reign, the influence of her husband was Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and their almost complete withdrawal from public life after his death in 1861. A total of Victoria interpreted its role as constitutional monarch very unconventional and quite confident.

With a total reign of 63 years, seven months and two days, Victoria was the longest reigning British monarch before being surpassed by Elizabeth II on September 9, 2015 . Because of her numerous offspring, she was nicknamed "Grandmother of Europe"; For example, she is both great-great-grandmother of the current Queen Elizabeth II and of her husband, Prince Consort Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, who died on April 9, 2021 .

The death of Victoria ended the rule of the House of Hanover , which passed to the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha when their eldest son Edward VII took over the throne (renamed House Windsor in 1917 ).

Life

Family background

The sudden death of Princess Charlotte Augusta , the only daughter entitled to the throne to the throne of Crown Prince George, Prince of Wales , who died for the incapable of reigning King George III. reigned, sparked a political crisis in Britain. In 1817 the British royal family lacked legitimate descendants to maintain the line of succession. Of the seven sons of George III. at that time only three were appropriately married. However, the connection between the Prince of Wales and Caroline von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel was considered to have failed, the marriages of the Duke of York and Albany and the Duke of Cumberland have so far been childless. For the still unmarried sons of the king, the death of the princess was the impetus to look for suitable wives among the Protestant noble houses of Europe in order to produce legitimate descendants entitled to the throne.

The ambitious Leopold von Sachsen-Coburg-Saalfeld , for his part, sought a connection between the House of Coburg and the British royal family and in 1814 - even before he had married into the royal family through his marriage to Charlotte Augusta - had his sister Victoire , widowed Princess of Leiningen , acquainted with Edward Augustus, Duke of Kent and Strathearn , fourth-born son of George III. After the death of Charlotte Augusta, the marriage plans were forced and the marriage finally arranged ( marriage policy ). Securing the continued existence of the Hanoverian dynasty was not the only reason for the Duke of Kent to marry. Heavily indebted and, due to his choleric and often sadistic leadership style, relieved of his military posts since 1803, he combined the hope of increasing his appanage with a marriage . The dynastic and personal interests thus led to a double wedding on July 11, 1818, in which the Duke of Kent married the Princess of Leiningen and his brother William, Duke of Clarence and Adelheid von Sachsen-Meiningen married.

birth

A few weeks after the wedding, Victoire, now Duchess of Kent, became pregnant. In order to secure the right to the British throne for the unborn child , Edward Augustus and his wife returned to Great Britain from the small German town of Amorbach before the birth . In the presence of high dignitaries, Victoire gave birth to a healthy girl on May 24, 1819 at Kensington Palace . For that time, unusually, the princess with the help of the first was gynecologist Germany, midwife Charlotte von Siebold given birth, immediately after birth against smallpox vaccinated and from her mother even breastfed . The father wrote to his mother-in-law in Coburg that the girl was "fat as a partridge" ("plump as a partridge"). The birth was mentioned in the newspapers but received little public attention.

On June 24, 1819, the princess was baptized in the domed hall of Kensington Palace by the Archbishop of Canterbury and the royal baptismal font was brought from the Tower of London especially for this ceremony . Due to the naming, there had previously been disagreements between the parents and Prince Regent Georg . The parents had suggested a number of first names common at the time, which the Prince Regent had refused and only allowed the two, rather unusual names Alexandrina (after her godfather Tsar Alexander I ) and Victoria (after her mother). In addition to the Prince Regent and the Russian Tsar, Victoria's paternal aunt Queen Charlotte Auguste von Württemberg and the maternal grandmother Auguste von Sachsen-Coburg-Saalfeld were godparents of the princess .

Her Royal Highness Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent stood behind her three uncles - Prince Regent George (from 1820 King George IV.), The Duke of York and Albany and the Duke of Clarence - and her own father initially in fifth position in the British line of succession. If legitimate descendants should emerge from the marriages of their father's older brothers, they too would have been entitled to the throne before Victoria. From June 1830, however, Victoria was generally regarded as the first candidate for the British throne ( Heiress Presumptive ).

Education and the Kensington System

During a stay in Sidmouth , Victoria's father died of complications from pneumonia (January 23, 1820), at which time his daughter was only eight months old. The royal family met the widow with rejection, George IV , the new monarch since January 29, 1820, had always viewed his brother's marriage to Victoire critically and therefore preferred his sister-in-law to return to her German homeland. In view of the horrific debts, the Duchess of Kent had to turn down the inheritance of her late husband and could only continue to live at Kensington Palace on the advice and with the financial support of her brother Leopold . Due to their isolated position, Victoire came increasingly under the influence of John Conroys , whom her husband had appointed as the administrator of the estate and who would soon take a dominant position in their household.

Victoria, called "Drina" in family circles, was considered a strong-willed, robust child who occasionally broke out in fits of rage . In 1824 the German pastor's daughter and later Baroness Louise Lehzen became governess of the five-year-old princess and was henceforth responsible for her education. Lehzen became a crucial caregiver for the adolescents, especially since the relationship between Victoria and her mother was increasingly tense. Because of the household controlled by Conroy, Lehzen was, although insufficiently qualified, responsible for preparing Victoria for her role as future monarch. Victoria later judged Lehzen: "She was an admirable woman, and I adored her, although I was also afraid of her." Victoria enjoyed a superficial education that corresponded to the young noble daughters of her time. From 1829 she was taught by the liberal Anglican clergyman George Davys , later Bishop of Peterborough , who had been appointed official tutor . Their program consisted of five lessons per day, six days a week, with an emphasis on biblical studies , history, geography and language learning. Victoria later spoke fluent German and French as well as some Latin and Italian . In everyday dealings with her mother, she spoke exclusively in English , as the Duchess considered this to be politically opportune. The pupil's willingness to learn was described as limited. Later on, dance, painting, riding and piano lessons completed the princess’s training program.

Presumably through a book on English history, Victoria learned of her position as Heiress Presumptive in March 1829 , whereupon she is said to have said to Lehzen: "I will do my best" ("I will be good"). Some authors refer such statements to the area of legends.

Meanwhile, John Conroy also assessed the possibility of taking over the throne of Victoria as very high if their uncles' marriages did not result in legitimate descendants. In view of the advanced age and poor health of Wilhelm IV , who had succeeded his brother George IV in 1830, this would presumably take place at a time when Princess Victoria would not have reached the age of majority. In this case, the Duchess of Kent, according to the Regency Act , would exercise the regency in place of her daughter, who was still underage , and Conroy would thus indirectly gain political influence. This project presupposed that the Duchess and her daughter should have as little contact as possible with the royal court, which is why Conroy specifically isolated and controlled them in Kensington Palace ( Kensington system ). He persuaded the Duchess that the Duke of Cumberland - the next in line to the throne after Victoria - was after the princess and that an isolated, closed life was necessary. For example, Victoria was forbidden to attend her uncle 's coronation ceremonies on September 8, 1831 . Only people selected by Conroy frequented the Duchess household; every daily routine was strictly regulated. Until the day of her own accession to the throne, Victoria had to spend the night in her mother's bedroom, meetings with other people were only allowed under supervision. She was not even allowed to go down a flight of stairs unaccompanied. Overall, Victoria had hardly any contact with her peers, her few playmates included her half-sister Feodora zu Leiningen , who was twelve years older than her , Conroy's daughter Victoire and, from 1833, the King Charles Spaniel Dash . Throughout her life Victoria was convinced that she had experienced a traumatic and unhappy childhood: "No outlet for my strong feelings and affections, no brothers and sisters with whom I could live (...) no intimate and trusting relationship with my mother," she wrote herself her eldest daughter.

A targeted preparation of Victoria for her role as monarch was deliberately omitted. An exception was her uncle Leopold, who had been King of Belgium as Leopold I since 1831 and resided in distant Brussels . In numerous letters he advised his niece, recommended her books and manuscripts that should prepare her for the assumption of the throne, which is why Victoria thanked him in letters and called him her "best and kindest advisor".

When it became foreseeable that Victoria would be of legal age at the time of her accession to the throne, Conroy tried to wrest her the admission to appoint him after the change of the throne as her private secretary . Despite the enormous pressure that her mother also exerted, as well as a severe illness (presumably typhoid ), 16-year-old Victoria Conroy steadfastly refused to sign his appointment as private secretary in October 1835. This led to a complete break with her mother, and by the time she ascended the throne, the two hardly exchanged a word with each other. Conroy meanwhile spread the rumor that Victoria was too mentally unstable to bear the responsibility of a monarch.

When William IV retired to Windsor Castle due to illness in the spring of 1837 and his life was drawing to a close, Victoria's succession to the throne was imminent. During the birthday dinner on the occasion of her 18th birthday and thus of age (May 24th, 1837), the already sick king declared that he was grateful to see this day, because in this way he had succeeded in preventing a reign of completely unsuitable people to have. This public declaration caused a social uproar and led to a rift between the king and his sister-in-law. Therefore Leopold sent his confidante Christian von Stockmar to Great Britain, who was to advise and support Victoria in the following months. With Stockmar's support, she managed to fend off the last attempts at influence by John Conroy.

Accession to the throne

On the morning of June 20, 1837, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chamberlain went to Kensington Palace and asked for an audience with Victoria. They revealed to the princess that her uncle Wilhelm IV had died that night and that the royal dignity had fallen to her. Victoria noted in her diary:

“I was woken at 6 o'clock by Mamma who told me the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Conyngham were here wishing to see me. I got out of bed and went into my living room (only in my dressing gown) and received her alone . Lord Conyngham then informed me that my poor uncle, the king, was divorced about two twelve from the life and consequently that I Queen am

(I was awoke at 6 o'clock by Mamma, who told me the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Conyngham were here and wished to see me. I got out of bed and went into my sitting-room (only in my dressing gown) and alone , and saw them. Lord Conyngham then acquainted me that my poor Uncle, the King, was no more, and had expired at 12 minutes past 2 this morning and consequently that I am Queen . "

Victoria received Prime Minister Lord Melbourne that same morning and attended her first Privy Council meeting. She had signed the first state documents as Alexandrina Victoria , after a few days she limited herself to using the ruler's name Victoria . With the change of the throne, the personal union between Great Britain and Hanover , which had existed since 1714, ended , as the Sali law applicable in the Kingdom of Hanover excluded female succession to the throne. In Hanover, her uncle Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale inherited the throne as Ernst August I and was a heir to the British throne until the birth of Victoria's first child ( Lord Justices Act 1837 ).

As early as July 1837, Victoria moved her court from Kensington Palace to the converted and expanded Buckingham Palace , which for the first time served as the official main residence of the British monarchy. Victoria used her new position to get rid of the dominant influence on the part of her mother and especially John Conroys. The Duchess of Kent moved to Buckingham Palace with her daughter, but was housed in a wing of the palace that was a long way from the Queen's private quarters. At court she was only given the role that protocol provided for her. Mother and daughter only met on official occasions in the presence of third parties. Conroy received no official position at court; but he remained a member of the household of the Duchess of Kent and did not leave it until 1839. Louise Lehzen, a close confidante of Victoria, was entrusted with the management of the royal household as "Lady Attendant" .

As monarch, Victoria was entitled to the income of the two royal duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall in addition to the annual donation of 385,000 pounds (which corresponds to the current amount of the equivalent of 17.6 million pounds) from the civil list , which enabled her to pay off her father's debts .

The coronation took place on June 28, 1838 at Westminster Abbey . The Parliament had approved 79,000 pounds for the ceremony, more than double what had been William IV. In 1831 is available. On Coronation Day, Victoria was escorted in the gold state coach with a pageant from Buckingham Palace, via Hyde Park , Piccadilly , St. James's Square , Pall Mall , Charing Cross and Whitehall , to Westminster Abbey. After two very unpopular predecessors, the young monarch was greeted with enthusiasm and was considered energetic, humorous and fun-loving among the people. Four hundred thousand visitors are said to have come to London for the coronation celebrations . Since Victoria found the Edwardian crown too heavy, the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Howley , crowned it in a five-hour ceremony with the Imperial State Crown made especially for her ( main article: Coronation of British monarchs ). For the first time, the members of the House of Commons also took part in the coronation, which underscored the increasing democratization of Great Britain. On the occasion of the event Victoria remarked in her diary: “I really cannot express how proud I feel to be the queen of such a nation.” (“I really cannot say how proud I feel to be the Queen of such a nation. ")

First years of government

Victoria's first Prime Minister was Lord Melbourne , who was to become Leopold's second paternal mentor and advisor to the 18-year-old Queen. He enjoyed the full confidence of his monarch and since she had initially waived the appointment of a private secretary ( Private Secretary of the Sovereign ), Melbourne also took on this area of responsibility. Victoria and the 58-year-old widower developed a close relationship - in addition to political issues, he also advised her on private and fashionable matters - which is why this intimacy was often interpreted as being in love with Victoria. Melbourne brought her closer to the history of the House of Hanover during audiences that took place almost every day or hours of joint rides, and gave her an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of leading politicians; Skills that were valuable to Victoria in the years that followed. He made it clear to her that as a constitutional monarch she represented the state and was not allowed to express any other opinion than her government in public. Melbourne did not show how much the queen's naivete, political inexperience and ignorance surprised him and tried to fill the gaps in her upbringing and education.

With the support of its prime minister, Victoria's first year in office was successful, but Melbourne's good offices only lasted as long as its government remained stable. After losing the majority of votes in the House of Commons , Lord Melbourne resigned his office as Prime Minister in May 1839 and since neither the Conservative Tories nor the Whigs had a sufficient majority in Parliament, Melbourne hoped that the new government would fail and that the new elections would be his Should strengthen the party. The politically inexperienced Victoria remained hidden from this plan, she felt the thought of an impending resignation of her prime minister and a takeover of government by the Tories under Robert Peel as a personal and political catastrophe. Peel, who was ready to form a minority government , considered a personal adjustment of the court to the future balance of power to be inevitable and demanded that the queen dismiss some ladies-in-waiting from Whig circles and replace them with women from the Tory circle. Victoria, who viewed her ladies-in-waiting as friends and close companions, whose selection she saw as a private matter, categorically refused this request, especially since Peel seemed unsympathetic to her ("cold and strange man"). When Peel refused to form a government under these circumstances, Lord Ashley was offered the office of prime minister, but he too refused under these conditions. Eventually the Tories gave back the government mandate and the Whigs under Lord Melbourne stayed in government. The queen celebrated her refusal as a political victory and was convinced that she had defended the dignity of the crown. With her categorical refusal, Victoria moved in this so-called " court lady affair " ("Bedchamber crisis") in a constitutional gray area, which earned her a lot of public criticism.

The ladies-in-waiting affair and Victoria's imprudent behavior in the Flora Hastings affair , in which Flora Hastings, a lady-in-waiting of the Duchess of Kent suffering from a liver tumor , was wrongly suspected of an illegitimate pregnancy, cost the queen public respect and sympathy. Victoria was no longer considered the innocent queen, but a cold, heartless woman who, along with her gossipy Whig ladies-in-waiting, had ruined an innocent reputation. In neither of the two affairs had Lord Melbourne reacted as resolutely as might have been expected of him as the adviser and confidante of an inexperienced monarch. Victoria herself judged the behavior in her first political action 60 years later with the sentence: "It was a mistake." Research has repeatedly rated her rejection of Peel as an immature decision - a typically emotional act by an inexperienced young woman. In public, there were increasing calls for the Queen to marry, as it was hoped that a husband would have a moderating influence on Victoria, who often acted very emotionally.

Marriage to Prince Albert

Leopold I and his advisor Baron Stockmar were firmly convinced that a marriage between Victoria and her German cousin Albert von Sachsen-Coburg and Gotha could not only serve Coburg's interests, but also make the Queen a better ruler, and arranged a connection between them both. Seventeen-year-old Victoria had already met her future husband in the summer of 1836 during a visit from her maternal uncle, Duke Ernst of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha , and his sons in London. The princess was able to warm to her two cousins and after their departure wrote to Leopold that Albert had all the qualities she wanted. For the first time she felt the prospect of “great happiness”. The letter to her uncle is evidence that Victoria knew that King Leopold saw Albert as the right candidate for her marriage.

On Leopold's initiative, Prince Albert and Prince Ernst came back to visit the British royal court on October 10, 1839. Victoria noted in her diary: "I saw Albert with some movement, he is beautiful." Just four days later, she revealed her intentions to marry to Prime Minister Melbourne and on October 15 - in accordance with the protocol - asked for Albert's hand. "I am the happiest person," said Victoria, describing her impressions in her diary. The speed with which Queen Victoria put aside her aversion to marriage and fell in love with Albert also explains his biographer Hans Joachim Netzer with the young queen's need for a supporter and protector, as she felt increasingly insecure in her role as regent Victoria's biographer Carolly Erickson cites this as the main reason. At the same time, she emphasizes a number of similarities: Both were emotionally hurt by an unhappy and loveless childhood, romantically inclined and shared a love of music. While Victoria's diary entries testify to a happy exuberance of emotions, Albert's letters from this period suggest that he saw the future marriage to the British Queen much more soberly. The reactions of the British public to the planned wedding were mostly negative, the German prince from the insignificant Coburg was not considered equal. In Great Britain, mocking verses appeared that the queen had given half a crown to receive a ring. Others alluded to the increasingly plump body of Victoria and assumed Prince Albert, another "lucky Coburger", that he would only take the fat queen because of her even thicker moneybag. British history lacked comparable precedents as to what title the consort of a ruling queen should take, and Prime Minister Melbourne accepted that this decision in Parliament was made to Albert's disadvantage. So this was after the wedding, a simple Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and one was not in the privileged rank Prince Consort ( Prince Consort ) levied. The Parliament, the Prince Leopold in 1816 even as the husband of the heiress presumptive Charlotte Augusta an annual alimony was awarded 50,000 pounds, Albert approved to only 30,000 pounds. Queen Victoria took this affront so personally that she considered not inviting the Duke of Wellington to the wedding.

The wedding preparations led to the first tensions between the bride and groom. Prince Albert wanted at least part of his personal court staff and - trained by the example of King Leopold - to maintain a staff which either consisted equally of supporters of Tories and Whigs or was politically neutral. Victoria appointed all members of his household without taking into account the wishes of her future husband and, influenced by Lord Melbourne, chose only supporters of the Whigs. She appointed George Anson , a confidante of Melbourne, as private secretary - the most important office in the princely household . The queen's preference for the Whigs' party continued at the wedding ceremony. Only five Tories were invited to attend the wedding ceremony on February 10, 1840 in the Chapel Royal of St James's Palace .

First years of marriage

Queen Victoria made a strict distinction between private life and rulership, which is why Albert, who had been prepared for a co-shaping political role and for whom this was a reason for marriage, repeatedly complained that he played no role in political decisions. Albert, who had spent most of his life in close association with his brother, missed his brother's company in London and suffered from his isolated position. The members of the British aristocracy regarded the German prince as too educated and stiff. The scientists, artists and musicians whom he would have liked to have invited to evening events had to stay away from the court at the request of his wife. Victoria was only too aware of her insufficient education and felt that she could not take part in such conversations, which she found incompatible with her role as monarch. She did not share her husband's interest in politics, but claimed the role of ruler for herself. "I do not like that he takes on my role in state affairs," said Prime Minister Melbourne after he had said positively about a public appearance by Prince Albert. The politically insignificant Albert looked for fields of activity. He became a member of the Royal Society , studied English law with a London lawyer and assumed the presidency of the Society for the Abolition of Slavery. Albert had the parks of Windsor Castle redesigned, began to build a model agricultural estate and turned the Arabs of the royal riding stables into a small stud .

The largely uninfluential role of the prince changed with the birth of the children. Victoria became pregnant immediately after the wedding and on November 21, 1840, Victoria ("Vicky"), named after her, was born. After the birth, Albert took part in the Privy Council for the first time at the invitation of the Prime Minister and became politically active for the first time without the knowledge of the Queen during the second pregnancy that followed.

Given the financial situation, the political end of the Melbourne era was in sight and a takeover of the Tories under Robert Peel was imminent. In order to avoid a situation like the one that had arisen around the ladies-in-waiting affair in 1839, which had cost Victoria a lot of sympathy, Albert began negotiations with Peel in good time. Through his diplomatic action, he agreed with him that in the event of a change of government only three of his wife's ladies-in-waiting had to leave the court and be exchanged for supporters of the Tories. Victoria was initially furious about this agreement, but then came to terms with it and would later appreciate Peel very much. Albert's intervention was the first step that politically neutralized the British royal court. Trained by King Leopold and Christian von Stockmar , he was convinced that in a constitutional monarchy in which the prime minister was primarily obliged to parliament, the royal house as an institution had to take precedence over day-to-day political events and party-political decisions. When he left on August 30, 1841, Lord Melbourne advised Victoria to seek political advice from her husband; advice to be followed by the queen. At the time of the birth of Albert Edward ("Bertie") on November 9, 1841, her husband was already the most important advisor. He now had access to all documents presented to the Queen, drafted many of her official letters and influenced her decisions. According to George Anson , Albert "did indeed become, if not title, Her Majesty's private secretary."

What was probably the worst marital crisis then finally led the Baroness Lehzen to withdraw from the court: The royal descendants grew up in the nursery run by a governess who was under the influence of Lehzen. At the beginning of her second year, Princess Victoria was ailing, and when the parents returned from a trip, they found their daughter pale and emaciated. Victoria lost her composure after a critical remark by her husband and, in a fit of fury, accused him of a number of accusations. Albert then left the nursery without a word and wrote his wife in a letter that she could do whatever she wanted with the daughter. Should the daughter die, she will be responsible. Over the next few days, the couple only dealt with each other in writing. Albert sought advice from Christian von Stockmar; Victoria turned to Baroness Lehzen. Stockmar, whom the Queen valued as an advisor as much as her husband, informed her that he would leave the British court if such scenes were repeated, whereupon she relented in her reply:

"Albert has to tell me what he does not like ... if I am irascible, which I hope no longer happens often, he does not have to believe the stupid things that I then say, for example that it is a shame, to have ever married & so on, which I only say when I am not feeling well. "

Through this event Albert was able to make it clear to his wife that Baroness Lehzen was overwhelmed with the tasks entrusted to her, which is why she was advised to retreat into private life. Provided with an adequate pension , Lehzen left the court on September 30, 1842 and settled in Bückeburg , Germany, whereby Albert's influence on the royal household and finances was noticeable.

Overall, the almost twenty-one year relationship between Victoria and Albert was considered very fortunate. During her marriage, the queen was strongly influenced in all decisions, including political ones, by her husband, who, especially in his later years, was said to have been both king and prime minister at the same time. Victoria herself put it in a letter dated June 9, 1858 to her eldest daughter:

“I can never believe or admit that any other person has been fated as blessed as I have been with such a man, such a perfect man. Dad was everything to me, and it still is today. [...] He was everything to me, my father, my protector, my guide, my advisor in all things, I would almost like to say that he was both mother and husband to me at the same time. I don't think anyone has been completely transformed by the influence of my dearest papa as I have been. His position towards me is therefore a very unusual one, and when he is not there I feel paralyzed. "

Upbringing the children

Victoria, who had given birth to her first five children in six years and became a mother of nine within 17 years, felt each of her pregnancies and births to be torture and unreasonable (“I think more about the fact that we are like a cow at such moments or a bitch; that our poor nature appears so completely animal and banal ”). In order to reduce the pain and strain, Victoria had herself anesthetized by the doctor John Snow with chloroform, which was still controversial at the time, when her two youngest children were born . Based on their example, this new anesthetic technique spread in obstetrics. The queen reacted to pregnancy and childbed with moodiness, states of depression, nervousness and sudden outbursts of temper. Victoria rated the undirected movements of newborns as frog-like and unattractive and considered it, for example, a lack of education if her one-year-old daughter was still sucking on bracelets. Neither Victoria nor Albert had experience in dealing with and raising small children, which is why the pedantic Albert wrote a series of memoranda after the birth of his first daughter, which set out how their upbringing should go. On the occasion of the birth of Crown Prince Albert Eduard (later Eduard VII.), Who ranked above his older sister in the line of succession because of his gender, Christian von Stockmar also wrote a 48-page memorandum in which he wrote down the educational principles of the royal descendants in detail. Princess Victoria began taking French lessons at the age of one and a half, and German language lessons at the age of three. The intelligent and eager to learn princess met the high demands of her parents; her younger brother Albert Eduard, whom they had subjected to a rigorous learning and upbringing program, found it much more difficult to learn.

The parents saw the life of Victoria's father and his brothers as a warning example. Their unrestrained, extravagant lifestyle had cost the British monarchy a lot of prestige, and the marital conflict between George IV and Caroline von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel had even led the country to the brink of revolution. It was the ambition of both parents not only to let their children grow into morally stable personalities, but also to prepare them as well as possible for their future tasks. The royal family ( royal family ) became the chief representative of an ideal which was stylized from civil society for strength and virtue source and hotbed of resistance. Albert in particular wanted to keep the children away from the potentially corrupting influence of the court for as long as possible and preferred the quiet country life to the hectic capital, which is why the couple moved from Buckingham Palace to Windsor Castle. In order to provide a protected, private retreat for family life and the growing number of children, they acquired Osborne House, a 400-acre country estate on the Isle of Wight in 1845 . Albert was able to fund the purchase through significant restrictions on the Queen's private spending as well as the sale of the Royal Pavilion in Brighton . He then had the building extensively rebuilt and expanded according to his ideas in the Italian style, and the garden was also designed according to his specifications. A wooden house ( Swiss Cottage ) was imported for the children , in which the princes were to learn carpenters and gardeners, and the princesses were to learn housekeeping and cooking. In contrast to the Queen, Albert played a decisive and direct role in their upbringing: he took a large part in her teaching progress, sometimes taught them himself and spent a lot of time with his children to play with them.

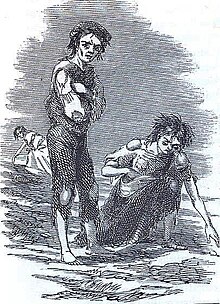

Famine in Ireland

→ See main article: Great Famine in Ireland

Ireland held a special position within the United Kingdom . Although the island had been part of the kingdom with its own representation in parliament since the 16th century, it was in fact treated as a colony . The policy of the British landowners , together with the potato rot and poor harvests , led to the great famine from 1845 to 1849 . As a result of this disaster, around one million Irish people lost their lives (around twelve percent of the population), and two million people emigrated to North America , Australia or New Zealand .

With his demand for the abolition of the grain tariffs ( Corn Laws ), in order to be able to import cheap grain to Ireland, Prime Minister Peel could not assert himself in the parliament against the big landowners. He received support from Albert, who, also on behalf of Victoria, wrote a memorandum in which he expressed their dismay and suggested suitable measures to alleviate the misery. His demands, such as the opening of the ports, as they had been successfully met in other countries affected by the potato rot, were initially not heard. When an even worse potato harvest was foreseen for the year 1846, Peel achieved the abolition of the grain tariffs, whereby he lost the support of his party and was replaced as Prime Minister by the Whig John Russell . Victoria, who was only allowed to express her sympathy for the Irish in private, donated 2000 pounds (not just 5 pounds, as is sometimes claimed) to the "British Society for the Relief of the Greatest Needs in the remote communities of Ireland and Scotland" . As an expression of her support for the Irish people, Victoria planned to purchase a country house in Ireland, but again distanced herself from this project, as this would probably have been interpreted as "Irish land lord behavior". Instead, she decided in 1849 to go on a royal tour of Ireland and the local people showed her enthusiasm and affection during the visit. The departure and re-embarkation took place under "every conceivable sign of affection and respect," said Victoria. Many contemporaries saw this visit as an opportunity for reconciliation, which the monarch did not take advantage of. In the years 1853, 1861 and 1900 Victoria made three further visits, but they did not offer the opportunities as they would have been possible in 1849. On the contrary, they even made the Irish feel that they had been abandoned by the British government.

Despite these events, Victoria was to have no significant influence on British social policy in the period that followed. On the one hand, because she knew this area was in good hands - Prince Albert was not indifferent to social conflicts because of Christian beliefs - on the other hand, because it was an area in which she found it difficult to cope. Wherever she experienced misery personally, she showed herself to be helpful, especially the common people in the Scottish highlands made the burdens of poverty understandable to her. The underprivileged classes below the bourgeoisie , however, remained alien to her. As a widow, Victoria was asked to take social policy measures several times in the 1880s, but this commitment should be understood more as an obligation to her husband than as a personal decision made out of deepest conviction.

Fascinated by the Scottish countryside the couple purchased in 1852 Balmoral Castle in County Aberdeenshire . This new acquisition was made possible by an unexpected inheritance: John Camden Neild had bequeathed all of his property - his property alone was worth over £ 250,000 - to the Queen, making Balmoral, like Osborne House, private property of the royal family. Balmoral was subsequently rebuilt according to Albert's plans in the baronial style and despite the initially very cramped space, Victoria preferred to stay far away in Osborne or Balmoral than in the "dark splendor" of Windsor Castle or the urban atmosphere of Buckingham Palace.

Revolutionary year 1848 and conflicts with Palmerston

After the first few years of Victoria's reign had passed without any significant political unrest, the European revolutionary year of 1848 was to have an impact on Great Britain as well. Against the express advice of Prime Minister John Russell , Victoria granted political asylum to the French King Louis-Philippe I, who had been overthrown by the February Revolution on February 24, 1848, and made Claremont House available to him. In Great Britain itself, speculators had caused enormous financial losses through inflationary railway stocks ( railway crisis ) and the price of wheat was at a low. The resulting financial crisis led to unemployment and poverty, which gave new impetus to the Chartist reform movement , which had formed at the beginning of the 19th century. The Chartists had announced a mass meeting in London for April 10, 1848, which is why the royal family was brought to Osborne House as a precautionary measure for safety reasons. Contrary to expectations , the event was non-violent , instead of the target number of 300,000 only 20,000 demonstrators gathered on Kennington Common, Chartist leader Feargus O'Connor brought a petition calling for liberalized civil rights and signed by more than a million people. Although the revolution in Britain had had little impact, Victoria first felt existential fear and saw the Chartists at fault:

“I believe that revolution is always bad for a country and the cause of unspeakable misery for the people. Obedience to the law and to the ruler is obedience to a higher power. "

The socio-politically harsh climate between 1840 and 1850 was certainly also responsible for the fact that five of the seven assassinations , which Victoria was to survive without injuries worth mentioning, occurred in this decade. The other two were perpetrated in 1872 and 1882. It was certainly no coincidence that the courts attested all of the defendants "mental disruption" and were careful to exclude political motives. It was not in the interest of the state to see the explosive nature of the social conflicts confirmed by conspiracies against the queen. Of course, it made an impression on the population with what self-control - rather unusual for Victoria - she endured these attacks on her life.

Through a policy of "fait accompli" drew Foreign Minister Lord Palmerston , who held the post since 1830 almost without interruption and enjoyed great popularity among the population, increasing disapproval of the Queen up. Instructions to the ambassadors were issued without Victoria's approval, letters to the monarch were opened in the State Department , personnel proposals from the Crown were ignored and ministerial decisions were communicated through the press. Palmerston indicated that the crown did not have to interfere in foreign policy, which was seen by Victoria as an indispensable monarchical prerogative and was increasingly seen as a question of British constitutionalism . When the minister declared the United Kingdom an ally of every liberation movement on the continent in the revolutionary year of 1848 , he also brought the peoples into play as a political power factor. With this liberal foreign policy, he appalled the queen, who, in contrast, viewed the dynastic entanglements of the European dynasties as a means of stabilizing international relations. She asked what effect this would have on Irish aspirations for emancipation . All attempts by the court to get rid of the unloved foreign minister - Victoria also referred to him as her “pilgrim stone” - failed. When Napoleon III. proclaimed the Second French Empire on December 2, 1851 in Paris after a successful coup d'état , the Queen expected her government to be strictly neutral . Foreign Secretary Palmerston, however, congratulated the French ambassador on the successful overthrow, which made his dismissal on December 22, 1851 inevitable. It would be the only time the Queen had actively secured the dismissal of a minister, and it would prove to be a mere political victory. Victoria's subsequent request for the government to come up with a program of definitive foreign policy guidelines that any future secretary of state should refer to was rejected by Prime Minister Russell. After the formation of a new government under George Hamilton-Gordon on December 28, 1852, the influential Palmerston joined his cabinet as Minister of the Interior before he took over the post of Prime Minister himself from 1855.

The Crimean War (1853-1856)

In March 1854, Great Britain and France joined the Ottoman Empire in the conflict with Russia known as the Crimean War . Through this intervention, Western powers wanted to counter the Russian expansionist drive on the Balkan Peninsula and on the Bosporus . The Crimean War is seen as the first “modern” and “industrial” conflict which, due to technical innovations, was characterized by costly material battles and trench wars ( siege of Sevastopol ). The conflict revealed the grievances within the British Army openly, in the army camps and especially in the field hospitals catastrophic conditions prevailed, which led to high personnel losses and finally in 1855 to the resignation of the Aberdeen government. In total, the British casualties amounted to 22,000 men, of which around 17,000 died due to insufficient supplies, disease or epidemics .

In accordance with their understanding of sovereignty , neither Victoria nor Albert were able to exert direct influence on military policy, but the authority of the Crown was great enough that their advice was heeded in the Cabinet and partially adopted. The monarch discovered her maternal duty of care for the army, showed compassion and personal concern for her soldiers by initiating military reform and supporting the renewal of the hospital system. Victoria, who first personally took part in a maneuver in March 1856 , showed keen interest in the military events and wrote with enthusiasm: “How do I regret that I am not a man and am allowed to fight in war. There is no better death for a man than to fall on the battlefield. ”In future she took the view that the troops should remain as far away from the influence of the politicians as possible, but should be in direct contact with the monarch through the commander-in-chief . As an expression of her support, Victoria donated the Victoria Cross on January 29, 1856, a medal to honor soldiers who had shown themselves to be particularly brave in the face of the enemy or excellent performance of duty during the Crimean War. Since its foundation, it can be awarded to any member of the British armed forces , regardless of rank. The medals were awarded on June 26, 1856 during a troop parade in London's Hyde Park . After the victory and the peace treaty on March 30, 1856 ( Peace of Paris ), Lord Palmerston, Prime Minister since 1855, thanked the Queen by saying that the task that he and his colleagues had to fulfill had been made comparatively easy by the " enlightened ideas that Your Majesty had in all great matters. ”The relationship between the Crown and Prime Minister had relaxed noticeably, Palmerston's energetic drive towards the end of the Crimean War and Prince Albert's tireless efforts as advisor and organizer had led to mutual rapprochement and appreciation. At the beginning of the war, Palmerston's resignation as Home Secretary triggered a sharp press campaign against Albert, possibly initiated by Palmerston himself. Among other things, the radical The Daily News had circulated rumors that the prince - who was still insulted as "German" - and even the queen herself had been imprisoned as a traitor in the Tower of London.

The open hostility in the press had shown Albert's still constitutionally undefined position. Victoria expressly wanted his influence on official business, even if there was no precedent for his position in the British Constitution. “I love peace and quiet, I hate politics and turmoil. Women are not made for governing and if we are good women, then we cannot love these male pursuits ”(“ I love peace and quiet, I hate politics and turmoil. We women are not made for governing, and if we are good women “We must dislike these masculine occupations”) is how Victoria described her view of politics. The prince had reformed the organization of the court, the bureaucracy and the finances of the crown. Albert directed and administered the royal household with considerable enthusiasm and acted as confidential advisor and private secretary to his wife. During their pregnancies, he himself had direct contact with ministers and government officials. Although his services to Great Britain were undisputed, he only enjoyed public popularity during the first Great World's Fair, which he initiated in 1851. After Parliament Alberts appointment as Prince Consort ( Prince Consort had again rejected), conferred on him Victoria on June 25, 1857 this privileged title itself. Due to a lack of description of the powers of this position, the government provided only officially, the Prince Consort have the right to To support the monarch in an advisory capacity. The extent of this consultancy activity was by no means defined.

On January 27, 1859, at the age of 39, she became a grandmother for the first time; their eldest daughter Victoria gave birth to Prince Wilhelm of Prussia, who later became Kaiser Wilhelm II , in Berlin .

Widowhood

The death of her 74-year-old mother on March 16, 1861 hit Victoria badly, which is why Prince Albert, who himself suffered from chronic respiratory problems, took over numerous tasks from his wife in the months that followed. Towards the end of 1861 Albert's health deteriorated noticeably before the royal personal physician William Jenner diagnosed typhoid fever on December 9th . Albert was not allowed to recover and died in the presence of Victoria and five of their nine children on December 14, 1861 at 10:50 p.m. at the age of 42 at Windsor Castle. In her diary, Victoria described the scene:

"Two or three long, very calm breaths, his hand squeezed mine and ... everything, everything was over ... I got up, kissed the dear heavenly forehead and cried in bitter pain:" O my love! ", Then I fell into silent despair on his knees and couldn't utter a word or cry a tear. "

“I will never forget how beautiful my darling looked when he lay there and the rising sun lit his face. His unusually shiny eyes saw invisible things and did not notice me anymore. Now there is no one left to call me Victoria . "

Typhoid fever was given as the official cause of death, but newer speculations assume gastric cancer , kidney failure or Crohn's disease , as Albert had been in poor health since 1859. The death of her husband was a painful stroke of fate for Victoria, which the desperate widow was never to overcome and which plunged her into the greatest personal crisis of her life. A week after Albert's death she wrote to Leopold I:

“The poor, fatherless baby of eight months is now a completely broken and destroyed widow of 42 years! My happy life is over! The world no longer exists for me! If I have to go on living (...), from now on only for our poor, fatherless children, for my unhappy country that has lost everything through its loss, and only to do what I know and feel that it would want ; because he is close to me, his spirit will guide and illuminate me! (...) His great soul now enjoys what is worthy of it. And I don't want to envy him, just pray that my soul will become more perfect in order to be allowed to be with him in eternity; for I sincerely long for this blessed moment. "

Victoria made her eldest son jointly responsible for the early death of her "beloved Albert". "Oh! This boy - to my great regret, I can or will never be able to look at him without a shiver ("Oh! That boy - much as I pity I never can or shall look at him without a shudder") ", she confided in her diary. The easygoing and dissolute Bertie was involved in an improper love affair with the Irish actress Nellie Clifden , which is why Albert, who was already ill, traveled to Cambridge on November 25, 1861 to speak to the heir to the throne during a long walk in the rain. Victoria wrote: "He was killed by this terrible business" ("He had been killed by that dreadful business"), which is why the relationship with her son was permanently strained. Bertie , whom she accused of indolence and indifference, to make her male support and to let him grow into the role of his father, rejected Victoria all her life.

An incessant phase of mourning began for 42-year-old Victoria, which - even for the circumstances at the time - took on strange forms and ritualized the memory of the deceased as a cult: Albert's death room in Windsor remained unchanged, furnishings and utensils became relics, his sheets and towels were changed regularly, and hot water was provided in his bedroom every evening. As an expression of deep sadness and appreciation for her husband, who died early, Victoria wore widow's costume until the end of her own life. Almost all of the photos and paintings show her as a woman in black mourning clothes, with a melancholy or dignified expression on her face. At the express request of the Queen, Albert was not buried in St George's Chapel , but in the Royal Mausoleum of Frogmore in Windsor Park, which Victoria had commissioned especially for both of them and in which she was later laid to rest. Overwhelmed by grief, the once so fun-loving Queen initially withdrew completely from the public and tried to avoid Buckingham Palace for her entire life. She went to the seclusion of Balmoral Castle or Osborne House and much to the chagrin of the politicians who were cited there, the stays during her 40 years of widowhood were firmly integrated into the course of the year. Even during government crises, Victoria could hardly be persuaded to return to London and had to be begged by the members of the government in order to enable efficient contact. She consistently refused to fulfill her public duties as representative of the monarchy, and did not appear again until February 6, 1866 for the opening of parliament in the House of Lords ( State Opening of Parliament ). In her 40 years of widowhood, Victoria only appeared seven times in person (1866, 1867, 1871, 1876, 1877, 1880 and 1886) for the annual opening of parliament, which she disparagingly referred to as the “State Theater” and was otherwise represented by the Lord Chancellor . She was only willing to appear in public for the inauguration of Albert monuments and even traveled to Coburg in 1865.

Even if Victoria continued to carry out her official duties conscientiously, she came under fire for years of public absence and became increasingly unpopular with the people. For many subjects, the "Widow of Windsor" ("Widow of Windsor") became a somewhat strange hermit in a widow's dress, a remote figure, awe-inspiring and ruling over a global empire , which at times gave the proponents of a republic great popularity. Constitutional lawyer and newspaper editor Walter Bagehot put it this way: “For reasons that are easy to name, the Queen's long retreat from public life has inflicted almost as much damage on the popularity of the monarchy as the most unworthy of her predecessors did with his viciousness and frivolity ". After her apprenticeship with Lord Melbourne, the journeyman's years with Prince Albert and a transitional phase of several years, she now had the confidence to rule as an independent constitutional monarch. Whenever she wanted to assert her political will against the respective prime minister in the following decades, she bluntly threatened her abdication, not without pointing out that this would be easy for her because this crown was a “crown of thorns” for her. In the four decades of her widowhood, she was always able to gain an emotional advantage politically and often assert herself.

With the Royal Albert Hall and the Albert Memorial Victoria commissioned the establishment of a national memorial in honor of her husband.

John Brown

A significant part of the mental relaxation of the widowed Victoria was attributed to her long-time servant John Brown , who was initially employed as a Scottish hunting assistant to Prince Albert in Balmoral. Since Victoria refused to be accompanied by a strange groom , Brown took over this task in the winter of 1864/65 and soon his duties extended beyond leading the horse. The queen liked him as a reliable, discreet servant , she took to her constant companion and 1865. The Queen's Highland Servant ( The Highland servant of the Queen appointed). In a memorandum, she defined its tasks: Brown was responsible for safety on horseback and in the carriages, for her clothing in the open air and for the dogs. The Queen showed her servant great sympathy, among other things because of his open-hearted expressions without regard to rank and status as well as his casual, rustic behavior. He entered Victoria's room without knocking, called her quite simply "Woman" and gave the orders in public, despite being accompanied by a class. In June 1865 the relationship became the subject of widespread gossip. The trigger was a painting by the painter Edwin Landseer , which shows the Queen on horseback, whose reins John Brown is holding. From the working sessions, Landseer reported that the Queen had devoured a certain Scottish servant and did not want to be served by anyone else. In the tabloids, John Brown was the target of cruel jokes, there were rumors that he was Victoria's lover or even secretly married to her, which is why the Queen herself was disparagingly referred to as Mrs. Brown . When Victoria made a trip to Switzerland in 1868 , rumors arose that the then 49-year-old Queen had given birth to her servant there.

Victoria's environment and the family rated Brown's behavior as tactlessness and naughtiness, which is why they tried in vain to get rid of the favorite. Most of all, he was envied for his numerous privileges: Brown granted hunting and fishing rights on the royal estates in Scotland, and it was common knowledge that a recommendation from the Highlander for a post or promotion was more beneficial than that of a prince. Victoria also demanded that Brown be treated particularly politely and considerately, which annoyed dignitaries at court.

In 1872 Brown prevented an assassination attempt by the Fenian Arthur O'Connor in front of Buckingham Palace , which gave the Queen another reason to insist on the services of her Highland servant. She donated the gold Victoria Devoted Service Medal for a special act of sacrifice to the monarchy, the first being given to John Brown. He later received a Silver Faithfull Service Medal for ten years of loyal service. Victoria is said to have personally determined the design of both medals. In addition to all these indirect favors, there was also concrete evidence in the form of very personal gifts: In 1869 a volume of poetry in Scottish dialect was dedicated “from his sincere friend VR”, in 1875 he received a gold watch, in 1879 a leather-bound Bible “from his loyal friend VRI ". The Queen also gifted him a house above the Dee where Brown would live after his retirement, and although the Queen rarely attended funerals, she appeared in person at the memorial service for Brown's father. Eventually he was even awarded the title of Esquire . As the years went by, the relationship became less and less the subject of rumors, but rather Brown's presence was recognized as a sign of attentive care, which it likely was. Brown took on the task of bringing bad news to the Queen himself, and in 1878, for example, brought her news of the death of her daughter Alice , who had died exactly on Albert's death day. Victoria also sent him to inquire about the sick and dying, which is why his presence could be seen as a sign of Victoria's special and personal sympathy.

After the death of John Brown on March 29, 1883, the Queen wrote in her diary that she was “terribly moved by this loss, which has robbed me of a person who has served me with so much devotion and loyalty and so much for my personal well-being did. With him I am not only losing a servant, but a real friend. ”Brown“ didn't leave her for a day for 18½ years ”- Victoria dedicated the second volume of her diary entries to him.

Between Gladstone and Disraeli

Under Victoria's reign, ten prime ministers headed the government, and their relationship with these statesmen was very different. Particular attention was paid to Victoria's personal affection for the conservative Benjamin Disraeli and her aversion to his political rival, the liberal William Gladstone , both of which shaped British politics in the second half of the 19th century - Disraeli foreign policy, Gladstone domestic policy. From 1868 until Disraeli's death in 1881 they took turns at the head of the government. To Victoria's chagrin, Gladstone's reign (1868 to 1874, 1880 to 1885, 1886, 1892 to 1894) was twice as long as Disraeli's (1868 and 1874 to 1880).

Already during his first term of office (February to December 1868) the charming Disraeli had succeeded in winning over the "fairy queen" ("The Faery"), as he called Victoria. He skillfully exploited her weaknesses, created an atmosphere of familiarity, showed exaggerated respect and thus gave the queen a sense of self-affirmation, which is why his return to the office of prime minister was downright longed for by the monarch after the Tories' electoral victory in 1874 . Disraeli made Victoria feel that he was her minister and permanent servant and that the country was jointly governed. As a special token of her favor, she allowed him to sit in her presence during the audiences; a privilege she had granted only to Lord Melbourne besides himself, and Disraeli became her “Melbourne of old age.” Victoria was particularly taken with his foreign policy, and the imperial self-confidence prevailing in Great Britain at this time made it possible for Disraeli, the personal desire to enforce the Queen's parliamentary title after another title. Through the founding of the German Empire in 1871, her eldest daughter was Vicky , with the Crown Prince Frederick William of Prussia was married to designate Empress and opposite her mother formal precedence would have had. Hardly anyone in Great Britain regarded the titles as not being equivalent, but the class-conscious queen feared for her rank. A change in the British title would not have been enforceable, but since Victoria was considered Empress ( Kaisar-i-Hind ) in India , she endeavored to officially bear this title. The proposal was not new: Disraeli had already pointed out during the Indian uprising of 1857 that it was important to bind all layers of the Indian people more closely to the crown. At the instigation of Disraeli's Parliament adopted the Royal Titles Act , the Victoria on May 1, 1876 in the rank of Empress of India ( Empress of India ) rose. From then on, Victoria signed with the abbreviation VR & I. (Victoria Regina et Imperatrix) , which became a symbol of the heyday of British imperialism . The proclamation in Delhi took place on January 1, 1877 as part of a Delhi Durbar , at which Victoria was represented by the British Viceroy . The appointment as empress was also the key catalyst for Victoria's return to the public. As a token of gratitude and appreciation, Disraeli was ennobled by the queen and she bestowed on him the hereditary title of Earl of Beaconsfield . After Disraeli's death (1881), Victoria described him as "one of my best, most devoted, and most amiable friends and one of my brightest advisers."

Victoria developed a special interest in India, which she was never to visit in person. She had a Durbar grand piano built in Osborne House especially for gifts of homage to Indian princes, she surrounded herself with an Indian bodyguard, invited Indians staying in Great Britain to an annual reception and founded the Order of the Star of India . From 1887 she employed a servant, Abdul Karim , who was promoted by her to "The Queen's Munshi " . Karim gave Victoria language classes in Hindustani and Urdu and taught them Indian customs, in later years the favorite became the "Indian Secretary of the Queen."

In the absence of personal intuition and experience, Victoria's knowledge of the colonies was limited to official documents and, under these conditions, it was hardly possible for her to see through the complexity of the problems. The numerous wars - for example the Zulu War (1879) or the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878 to 1880) - that were waged in her rapidly growing empire , Victoria now legitimized, unlike before, when it came to British issues, with civilizational principles Sense of mission; she considered them regrettable but necessary, while for civilizational reasons she continued to regard wars in Europe as reprehensible. "Because the local rulers cannot maintain their authority (...) Not to expand our colonial possessions, but to avoid war and bloodshed, we have to do this." Victoria thus justified colonial power politics as a policy to prevent war.

In contrast to the eloquent Disraeli, William Gladstone showed no interest in flattering the Queen; rather, the "People's William" was considered sober, matter-of-fact and pedantic. Gladstone endured his monarch's apparent dislike ("I could never have the slightest confidence in Mr. Gladstone after his impetuous, harmful, and dangerous behavior") while being loyal to her - without ever receiving credit - that he was her took active protection from opponents of the monarchy and enforced controversial apanage demands of her children in parliament. Under the influence of the Paris Commune and the continued absence of Victoria from public life, the opponents of the monarchy received a strong influx around 1870/71, which led Gladstone to urge the Queen to return to the public. On the occasion of the Crown Prince's recovery from typhoid fever, Victoria took part in a thanksgiving service in London's St Paul's Cathedral on February 27, 1872 . Her first appearance after nine years outside of the opening of parliament or the inauguration of Albert monuments. Victoria's appearance sparked great enthusiasm among the population and turned into a demonstration of affection for the royal family. “It was a very moving day and several times I had to suppress my tears” (“It was a most affecting day, and many a time I repressed my tears”) the moved queen confided in her diary. Gladstone's priorities were undoubtedly domestic politics, and from 1868 he headed the most important reform cabinet of the Victorian era. He abolished patronage of office in the civil service in favor of specialist exams, banned the sale of officers' certificates , opened the universities of Oxford and Cambridge to non-Anglican students, extended compulsory schooling up to the age of thirteen and introduced secret voting , thereby exerting influence on the landowners on the voting behavior of the dependent population should be prevented. In particular, defusing the Irish conflict caused Victoria to feel uncomfortable. Gladstone dissolved the Anglican state church in Ireland, improved the position of the Irish tenants ( Land Act ) and saw above all Irish self-government ( Home Rule ) as inevitable. For Victoria, who, like the majority of British people, actually viewed Ireland as a colony , this practice was shocking and she complained that her government did not have the power to pacify the country. The Queen showed a behavior towards the Prime Minister Gladstone that she should not have allowed herself as a constitutional monarch, in that she very unconventionally tested and occasionally even exceeded the limits of the constitution. She secretly tried to isolate Gladstone from his party, urged subordinate officials to abandon their loyal behavior to the government, and colluded with the opposition to the Prime Minister. Gladstone made himself particularly unpopular with Victoria because he hardly supported colonial imperialism and even rejected it out of moral values. Mainly because of his agitation against Disraeli's government from 1876 , but subsequently also his hesitant foreign policy during the Mahdi uprising in Sudan , Gladstone incurred the displeasure of his monarch, who claimed him personally for the military defeat during the siege of Khartoum and the death of the governor-general Charles George Gordon held responsible ( see Gordon Relief Expedition ). "The news from Khartoum is appalling, and the thought that previous action could have prevented all of this and saved many precious lives is too appalling." Victoria found the Crown's humiliation for Gladstone's indecision just as inexcusable like Gladstone the deliberate affront of his sovereign. When the 85-year-old Gladstone announced his departure from Prime Minister in March 1894, Victoria's dislike of him was still so great that she couldn't find any words for anything more than expressions of general regret during his final audience.

Late years of government

Great Britain was the leading trade, economic and maritime power at the end of the 19th century and took on the role of a “world policeman.” Foreign policy was characterized by the principles of splendid isolation and the Pax Britannica : other great powers were bound by conflicts in Europe while Great Britain deliberately did not intervene and was able to further expand its supremacy by concentrating on trade. In the mid-1870s, Victoria said goodbye to self-chosen seclusion and began to take part in public life again. People no longer saw in her the grieving, withdrawn widow who neglected her public duties as a monarch, but for them Victoria was the mother of the country , to whom they showed respect and affection. It gave the population a sense of continuity and consistency and became a symbol of the British Empire and its achievements. The monarchical traditions, personified by Queen Victoria, gave people support and security in an increasingly complex, changing world. For this purpose and for the empire's self-portrayal, the courtly rituals became more and more pompous, without this having any impact on the modest life of Victoria. The actual power of the crown had diminished considerably under Victoria's reign ( Reform Act 1867 ), but its prestige had grown enormously. The reputation of the monarchy was, however, tied to the person of Victoria and she in turn exuded a political power that should not be underestimated. As consistently as Victoria tried to influence the politics of her country, especially foreign policy, the social change and the social problems ( see main article: Social question ) left her largely untouched. Victoria gave its epoch its name, but it did not have a decisive influence on it.

In 1879, at the age of 60, she became a great-grandmother for the first time ; from Princess Feodora of Saxe-Meiningen .

Golden Jubilee of the Throne (1887)

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of her accession to the throne of the Golden Jubilee (was in 1887 Golden Jubilee ) organized. Fifty European monarchs and princes, with the exception of the Russian tsar, and numerous overseas delegations were expected in London for the main festivities, which were scheduled for May and June. In addition to parades, family dinners, official banquets and pageants, a service on June 21, 1887 in Westminster Abbey was the main highlight (“My sons, sons-in-law, grandchildren (...) and great-grandchildren came forward, bowed and kissed my hand, and I kissed everyone; the same ritual then with the daughters, daughters-in-law, granddaughters and great-grandchildren; they curtsied and I hugged them warmly. It was a very moving moment, and in some eyes I saw tears ”). With frenetic cheers, Victoria was escorted from Buckingham Palace to the Abbey in an open landau , escorted by Indian cavalrymen . For Victoria herself, the celebrations were overshadowed by concern for her seriously ill son-in-law, Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm. With the marriage of their eldest daughter, Victoria and Albert had once hoped to export British constitutionalism to Prussia and to create a British-Prussian alliance. Victoria was particularly depressed by the prospect that her grandson Prince Wilhelm (the future Wilhelm II), who, in her opinion , had inherited all the unfortunate traits of the Hohenzollern family , would apparently face an early assumption of office and a long reign. She doubted Wilhelm's personal maturity and experience for the office of emperor. The thought that he would be supported by her hated Chancellor Otto von Bismarck , whom she had met personally on a private family visit in April 1888, did not calm her in any way.

Diamond Jubilee (1897)

On September 23, 1896, Victoria's reign outlasted that of her grandfather Georg III. and she became the longest reigning monarch in English , Scottish, and British history . In accordance with Victoria's wishes, the celebrations on the occasion of her 60th jubilee on the throne were postponed to 1897. At the suggestion of the Conservative Prime Minister Lord Salisbury and the Colonial Minister Joseph Chamberlain , the Diamond Jubilee was hosted as the Festival of the British Empire . To demonstrate the size and power of the Empire, delegations from all colonies were to take part instead of the European monarchs. On the sidelines of the celebrations, the heads of government of the Dominions met for the first time for a conference ( Colonial Conference ).

On June 22, 1897, 78-year-old Victoria paraded in an eight-horse state carriage on a nearly ten-kilometer route through London, accompanied by troops from all parts of the Empire. An open-air thanksgiving service was held in front of the steps of St Paul's Cathedral , which Victoria had to attend while sitting in her carriage, as she could no longer climb the steps due to her rheumatoid disease. Eventually the procession crossed the poorer parts of London, south of the Thames . Victoria thought she was at the height of her popularity. Celebrations took place in the British colonies around the world, with countless fireworks, festive events, parades and church services for weeks.

Despite her advanced age, Queen Victoria continued to work hard and unwilling to let her eldest son participate in the business of state. Bertie was exposed to the persistent criticism of his mother, who repeatedly denied him the ability to fill the office of ruler ("totally, totally unfit for ever becoming king"). In the course of the costly and costly Boer War (1899-1902) in South Africa , the self-confident Victoria repeatedly urged her government to vigorously defend British interests: “Please understand that no one in this House is depressed; We are not interested in the possibility of defeat; They do not exist. ”(“ Please understand that there is no one depressed in this house; we are not interested in the possibilities of defeat; they do not exist ”).

death

Victoria, who had enjoyed stable health throughout her life, increasingly struggled with age-related physical ailments from the mid-1890s. As a result of falling down stairs in 1883 and rheumatism in her legs, she found it difficult to walk, which is why she was increasingly dependent on a wheelchair. In addition, cataracts permanently worsened Victoria's eyesight, which made reading and writing more difficult, but her mental vitality remained considerable. Against the background of the death of her son Alfred (in her diary she noted: "Oh, God! My poor darling Affie has also passed away. It's been a terrible year, nothing but sadness & one horror after the other.") And always As the Boer War became less popular, mental deficits first became noticeable in the summer of 1900 - the beginning of a physical decline that spread over the next few months without being able to be associated with a specific clinical picture. Victoria complained of general weakness, tiredness during the day, loss of appetite and insomnia . As usual, Victoria had spent the Christmas days and the turn of the year in Osborne House, at the beginning of January 1901 she felt “weak and unwell”, in mid-January she felt “drowsy… dazed and confused” (“drowsy… dazed and confused”) ), which is why her surviving children, with the exception of Vicky, who was seriously ill, came to Osborne and gathered at her deathbed. On January 22, 1901 around 6:30 p.m. Queen Victoria died at the age of 81 in the arms of her grandson Wilhelm II and her son Albert Eduard.

On January 25, her successor Edward VII , Kaiser Wilhelm II and Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught laid her in her coffin. Victoria's personal doctor made sure that a collection of favorite items was placed in the coffin, as she had ordered in a secret instruction. These included an alabaster cast of Albert's hand, photos, and a lock of John Brown's hair. Her wish to be buried in a white dress and with her bridal veil was also granted. On February 2, 1901, Victoria was laid out for two days in St George's Chapel at Windsor Castle and then buried next to Albert in the Royal Mausoleum of Frogmore , which she had built for herself and her deceased husband in the style of Italian Romanticism .

With a reign of 63 years, seven months and two days, Victoria was the longest-ruling British monarch before being surpassed by her great-great-granddaughter Elizabeth II on September 9, 2015 . The death of Victoria ended the rule of the House of Hanover , which had existed since 1714 , which passed to the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha with the assumption of the throne by their eldest son Edward VII (renamed House Windsor from 1917 ).

progeny

The connection between Queen Victoria and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha resulted in nine children:

- Victoria ( Vicky ) (born November 21, 1840 - † August 5, 1901), Princess Royal

- ⚭ 1858 Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia ; as Friedrich III. German emperor

- Albert Eduard ( Bertie ) (born November 9, 1841 - May 6, 1910), Prince of Wales ; as Edward VII King of Great Britain and Ireland, Emperor of India

- Alice (April 25, 1843 - December 14, 1878)

- Alfred ( Affie ) (born August 6, 1844 - † July 31, 1900), Duke of Edinburgh and ruling Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha

- Helena ( Lenchen ) (born May 25, 1846 - † June 6, 1923)

- Louise (March 18, 1848 - December 3, 1939)

- Arthur (May 1, 1850 - January 16, 1942), Duke of Connaught and Strathearn

- Leopold (April 7, 1853 - March 28, 1884), Duke of Albany

- Beatrice ( Baby ) (April 14, 1857 - October 16, 1944)

Victoria was so closely connected with her husband that she was rather indifferent to the children during his lifetime. After Albert's death, the children certainly meant more to her, but there was no sign of intimacy in their daily dealings with them. Her relationship with heir to the throne, Prince Albert Eduard, was difficult and a constant disappointment throughout her life. She even accused him of his looks (not unlike hers). Many sources claim that the strict upbringing of the heir to the throne severely hampered his development and caused many of his later behaviors. The relationship with the daughters was a lot better, especially in the later years. Victoria made sure that there was always a daughter close by as secretary and companion. Helena, Louise and Beatrice took over this task one after the other. She only agreed to Beatrice's marriage on the condition that she should continue to live with her after the wedding.

She was much more loving and indulgent towards her grandchildren and great-grandchildren, for example she looked after the children of her daughter Alice, who died at an early age. However, she often felt overwhelmed by the large number of her descendants and the personal financial burden that many of them represented, as Parliament saw no reason to publicly support descendants who did not succeed to the throne.

Grandmother of Europe

Victoria had 40 grandchildren and 88 great-grandchildren. She determined that all of her grandchildren should bear her name or that of Alberts. As a result of their marriages, she has descendants in almost all European monarchies, which is why she was nicknamed the "Grandmother of Europe". For them it was an instrument of peacekeeping to cover the European continent with a dense network of relatives on the princely thrones. How ineffective this form of peacekeeping was, was shown in the German-Danish War (1848-1851), in the German War (1866) and finally in the First World War (1914-1918), where the fronts ran across the kinship.