Tower of London

| Tower of London | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Aerial view of the fortress with the installation Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red |

||

| Creation time : | 11th century | |

| Castle type : | fortress | |

| Place: | London Borough of Tower Hamlets | |

| Geographical location: | 51 ° 30 '29 " N , 0 ° 4' 33" W | |

|

|

||

| Tower of London | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

| Contracting State (s): |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | (ii) (iv) |

| Reference No .: | 488 |

| UNESCO region : | Europe and North America |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1988 (session 12) |

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London (in German, in short: the Tower of London ) is a fortified complex of buildings on the north bank of the Thames near the southeastern edge of the City of London and at the same time in the center of the English region of Greater London ( London ). The ring castle with two fortress rings served the English and British kings as a residence, armory , workshop, warehouse, zoo, garrison, museum, mint, prison, archive and place of execution. The tower has been visited by tourists for 600 years. In 2011 it was the most visited paid attraction in the UK with more than 2.5 million visitors .

Originally the Tower was built in the 11th century as a fortress of William the Conqueror against the potentially hostile citizens of the City of London. Up until James I , all the English kings used the tower temporarily to stay. As the base of the British monarchy in the historic center of London, the Tower is closely linked to British history. The outer walls and towers of the tower were essentially built in the Middle Ages. In the centuries that followed, numerous additions and alterations were carried out within the walls. A redesign took place in the 19th century: walls and towers were rebuilt in neo-Gothic style, buildings within the walls were demolished.

Today there are exhibitions in the Tower about the building itself and its history, parts of the Royal Armories collection , the British Crown Jewels . The headquarters and museum of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers , living quarters for the Yeoman Warders as well as administrative and office space are located here. The Tower was home to the Board of Ordnance , the Royal Mint , the Ordnance Survey , the Royal Observatory , the Public Record Office and the London Zoo . The Tower is also the setting for numerous dramas and novels from Shakespeare to Edgar Wallace. In particular, writings and history paintings from the 19th century emphasize its role as a prison and contributed significantly to the tower's reception as a gloomy dungeon.

The UNESCO declared the Tower 1988 World Heritage Site . The tower belongs to the British Crown and is administered by the Historic Royal Palaces .

Building history

Foundation and expansion in the Middle Ages

After the conquest of England in 1066, the Normans under William the Conqueror built a number of fortresses to secure their power in the country. After it during the coronation of William the King of England in Westminster Abbey came at Christmas 1066 riots in the city, Wilhelm ordered the construction of a castle on a on the Thames located hill on the eastern edge of the City of London at. The fortress, about 200 feet by 400 feet (about 70 meters by 140 meters), was located in the southeast corner of Londinium's Roman city walls and was supported by the preserved Roman wall to the south and east, and by a moat with earthworks and wooden palisades to the west and north protected. This first fortress was replaced by a massive stone structure, the later White Tower , from 1077/78 . While Richard I went on crusades, William of Longchamp , the Lord Chancellor of England, began to convert the tower into a fortress with several buildings at the end of the 12th century. He strengthened the other walls around the White Tower, expanded the walls to the west and provided them with smaller watchtowers for the first time. Longchamp was the first to try to build a moat around the tower. But it still failed because of the current conditions in the Thames.

Heinrich III was decisive for the current shape of the tower . who extended the fortress to the mainland from 1220 to 1238 and to the river from 1238 to 1272. During this time, the entire fortress was named the Tower of London. Both the work on the great hall and other household-related constructions indicate that Heinrich wanted to upgrade the tower as a residential building, and wanted it to be on a level with Windsor Castle or the residences in Winchester and Clarendon . Heinrich had the king and queen's apartments redecorated and the walls whitewashed . He also had five tons of marble brought in from Dorset to fit out the interior.

After Heinrich had to hide in the tower for a month in the wake of the upheavals around the wedding of his sister Eleanor of England with Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, in front of angry nobles, he began to expand the tower as a fortress on top of the current one State of the fortress technology. He had a new fortress ring, a total of eight towers and a permanently filled moat built.

Edward I , who had extensive experience of warfare in the British Isles and the Continent, continued the ambitious building program of his predecessor. He expanded the inner wall so that a real ring castle was built, had a new trench dug and new outer walls built, so that a total of three defensive rings were created. The architecture followed the model of British ring castles developed in Wales . The fortress rings were raised from the outside in, so defenders on the inner rings could shoot over their fellow combatants on the outer rings. Should the outer fortress rings fall, the defenders would still have a height advantage.

Eduard replaced the big gate of his predecessor with two new gates, one to the water and one on the land side on the west (city) side of the fortress. St Thomas's Tower, named after Thomas Beckett , was built in 1275 . With this, the tower had reached its present size. In the times after Edward I, extensions and conversions followed rather sporadically, and often ad hoc. Eduard II. And Eduard III. had the outer wall built up in the 14th century to the height that is still present today.

Multiple renovations since early modern times

From the 16th century onwards, work on the actual defenses of the tower stalled. Numerous government agencies and organizations from the royal armory to the mint to the archive had meanwhile become at home in the Tower. Although these ensured regular new construction and an expansion of the inner buildings, they prevented the expansion of the defensive systems. Henry VIII had the fortress church of St Peter ad Vincula completely rebuilt, the Queen's House , the largest building of the Tudor period, built and the first defensive structures provided with loopholes for handguns.

Significant in the 17th century was the Grand Storehouse , which later fell victim to a fire. In addition, dozens of smaller buildings, apartment buildings and other structures were built. Among other things, there were two pubs on the outer wall of the tower, which were also demolished in the 19th century. The remaining medieval palace complexes outside the White Tower fell victim to two great fires in 1774 and 1788.

The last major new building took place in 1840, when the Chartists put Great Britain into an uproar and the British royal family had the tower brought back to the state of defense technology at that time. The construction of the Waterloo Barracks , which took the place of the old Grand Storehouse and is now the largest building in the fortress next to the White Tower, was a defining feature .

In the 19th century there was again a profound change in use. By 1850, the Royal Mint, Menagerie and Archives had left the Tower and moved to buildings further outside central London. Tourism and sightseeing increased in importance. In the 19th century, this was followed by major renovations inside. Buildings from previous centuries that were no longer needed were demolished and others erected. Following the fashion of the time, the builders tried to restore the tower to as medieval a state as possible.

Instead of building in brick with reminiscences of classical architecture, as in previous centuries , Anthony Salvin called for the use of natural stone, which should look as true to the original as possible from the Middle Ages. For both military and aesthetic reasons, the builders of the 19th century had numerous buildings removed from the fortress grounds. John Taylor's work sparked a heated dispute with the newly founded Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings , which led to one of the first fundamental discussions about modern monument protection in the 19th century.

The arrangement of the buildings in the tower has essentially remained the same since around 1900. From the 1960s, there was a further return to the history of the building. Extensive archaeological excavations began, and in several places restorers tried to restore the medieval state. For example, a wooden staircase was built for the first time in 300 years, making the original entrance to the White Tower accessible. Also in the 1960s, cleaning work began on buildings that had not seen this for centuries.

architecture

The ring castle of the tower originally consisted of three fortress rings, two of which can still be clearly seen. The tower occupies an area of 7.3 hectares. The innermost ring - innermost ward or coldharbour - consists of the White Tower and the courtyard surrounding it. It is the oldest part of the fortress. The inner ring - inner ward - includes the rest of the inner area with the Waterloo Barracks, the Church of St Peter ad Vincula, the open space of Tower Green and other residential, warehouse and administrative buildings. It is surrounded by walls with 13 other towers. The outer ring - outer ward - encloses the inner wall with a second wall. It has six towers facing the water and two semicircular bastions at the northwest and northeast corners of the fortress. Outside the walls are a moat, formerly filled with water, and some external structures. In the southwest area of the fortress, a bridge leads over the moat from the Middle Tower on the city side to the main entrance Byward Tower on the fortress side.

Surroundings

The tower is located directly on the Thames on the eastern edge of the City of London and thus forms the eastern entry point into central London. While the tower visually dominated the city around it for many centuries, this began to change after the Great Fire of London in 1666. St Paul's Cathedral , built by Christopher Wren , was similarly impressive. New, larger buildings replaced the medieval buildings that had shaped the cityscape up to that point. The large wharfs of the 19th century were built on a similar scale to the Tower, the Tower Bridge from 1894 towered over it. Since the 20th century, the city began to allow numerous high-rise office buildings near the tower, which were gradually replaced by larger buildings. Tower Bridge is located in the southeast of the fortress. To the east, its busy driveway - part of the inner city ring of London - leads directly past the Tower; Another main street, Byward Street (an extension of Lower Thames Street ) is to the north of the tower. These busy streets are bordered by narrow sidewalks, pedestrians are advised not to use them. However, the open spaces of Tower Hills in the west and the banks of the Thames in the south still allow an impression of the fortress that is not determined by the roaring traffic.

The location in the urban area is the result of various master plans in the 20th century that focused on the tower itself. They only included the area around the fortress in their planning to the extent that it was needed to smuggle visitors to the tower. This changed at the turn of the century. Under the title Tower Environs Scheme , the main entrances to the tower were redesigned between 1995 and 2004 and car traffic was banned from the west and south of the tower.

The Tower can be reached through the Tower Hill station of the London Underground , which about half of the Tower visitors use. Other visitors come via Fenchurch Street Station and Tower Gateway Station on the Docklands Light Railway , take a ship to Tower Millennium Pier , or take a bus in the parking garage under Tower Place .

Moat, outer wall and outer fortress ring

The trench is 36 meters wide and six meters deep. The brick surrounds date from the years 1670 to 1686. On the river side, the trench is narrower due to the construction, on the east side the approach to Tower Bridge is partly on the former trench area and cost this volume. On the south side is Tower Wharf, a stone quay that dates from the late 14th century in its current form.

On the land side there are two bastions in the north: Brass Mount in the northeast and Legge's Mount in the northwest. The larger brass mount seems a little older than the wall that encloses it. It is one of the oldest brick buildings in the British Isles. The smaller Legge's Mount was built together with the outer wall ring. It was increased between 1682 and 1686.

On the water side in the south, the tower is protected by several towers. The most striking building is the St Thomas's Tower, where the remains of a water gate with a boat entrance to the Thames can still be seen. The gate that allows land access to the tower from the south dates from the 19th century.

Later backfilling of the trench made the outer wall appear lower than it was originally. Only parts of the once elaborate access to the tower from the west have survived. From the Lion Tower southwest of the moat, only the remains of the foundation and the bridge system remain, which are visible in the moat. Today access to the tower is through the gate in the Middle Tower , then over a bridge over the moat and finally through the gate in the Byward Tower .

Directly behind the Byward Tower is the Bell Tower as the remainder of a fortification that protected the entrance to the tower. From the Byward Tower and Bell Tower, two streets run through the fortress ring. Mint Lane, which is not open to the public, leads north to Legge's Mount. There are casemates and various workshops from the 18th century.

The route to the east, Water Lane, runs parallel to the Thames and leads to the Bloody Tower. It is protected on the side by the Wakefield Tower . Through this, visitors get into the inner fortress ring. The inner wall from the Bell Tower to the Bloody Tower dates back to 1190, but has since been raised by brick structures and broken through with numerous windows. The waterside wall from the late 13th century was raised in the 1330s and, after weathering over the centuries, was comprehensively rebuilt in the years 1679 to 1680.

A second access to the river is through the Cradle Tower , which is east of St Thomas's Tower and also dates from the 14th century. The gate in this tower is significantly smaller than the Traitors' Gate. The upper areas of this tower were dismantled in 1777 to make way for a gun battery. During the neo-Gothic restoration of the tower under John Taylor in the 19th century, it was given a medieval-looking top again. The actual gate dates back to the 14th century.

Inner ring, innermost ring, and white tower

The gate from the outer to the inner fortress ring runs through the Bloody Tower. With the construction of the outer fortress ring, the Bloody Tower was subjected to various renovations: While the lower parts date from the 13th and 14th centuries, the constable of the tower had the tower raised in the 17th century to accommodate the prisoner Walter Raleigh . The uppermost buildings date from the 19th century. At the southeast corner of the inner ring is the Salt Tower , probably built in 1238. The three-quarter cylinder still has remains of a former connection to the outer wall. The top of the Salt Tower dates from the 19th century.

A conspicuous tower in the inner wall is the Beauchamp Tower in the west, the former function of which can be seen as a gate. In the north there are smaller towers from different centuries that are not open to the public. Similar towers stand in the east, over them the masonry runs. Lanthorn Tower and the wall between Bloody Tower and Lanthorn Tower are completely new buildings from the 19th century. The bare and straight part of the wall west of the Lanthorn Tower clearly shows its origins from the industrialized 19th century, it reminds little of the medieval walls in other parts of the tower. In the vicinity of this section of the wall, however, there are remains of the Roman walls facing the Thames, dating from around the 4th century. These were archaeologically excavated and examined from 1976 to 1977.

The large individual buildings of the tower are located in the inner ring. In addition to the Waterloo Barracks, this is the Church of St Peter ad Vincula, the New Armories , the former hospital, the former officers' building to the Waterloo Barracks, the Queen's House , which is overgrown with the inner wall , a former engine house and other residential buildings.

The innermost ring is hardly recognizable at first glance today. Most of the walls that delimited it have been torn down over the past few centuries or are now only in fragments. The wall in the west of the inner fortress ring came from the 11th century. In the east the former Roman city wall formed the border, in the north the White Tower delimited the area. Originally the protected area for the royal rooms within the inner ring was located here.

The remains of the Wardrobe Tower from the 12th century and the foundations of the Coldharbour Gate from the 13th century have been preserved on older fortifications .

In the middle of the area is the keep known as the White Tower . On an almost square base area of around 30 by 30 meters, the tower rises over almost 30 meters. In the southeast corner it has a semicircular ledge in which the chapel is located. The White Tower is designed in the Norman style . It consists of limestone that was mined in Kent and marlstone from the surrounding area, including recycled stones from Roman fortifications. The facade was decorated with stones from Caen when it was built ; in the early modern period this was almost entirely replaced by Portland Stone . The walls are 4.6 meters thick in the lower part of the tower and 3.4 meters in the upper part. The White Tower has shaped the name of the fortress since the Middle Ages. Although the fortress consists of numerous walls, towers, gates, houses, barracks and ditches, it was called the Tower in England for almost the entire period of its existence , as the White Tower was the visually distinctive building.

Usage history

The area around the tower was shaped over many centuries by the conflict between the crown and the city, which resulted from the tower's position as a fortress against London. Until the late 19th century, the tower was administratively separate from the city and had its own taxes, police, judiciary and prison. Since 1686, the Tower Liberties included not only Tower and Tower Hill, but also three other areas in the city area. Since the early 19th century, various police laws restricted the rights of the liberties and transferred the powers to the city of London. From 1855 Tower and Liberties belonged to the Whitechapel District , from 1900 to the Metropolitan Borough of Stepney , from 1965 to the London Borough of Tower Hamlets .

Residence (1078 to 1533)

Originally, the first completed White Tower served as the apartment of the English kings in the tower. But as early as 1171/1172, written evidence for other living spaces on the fortress grounds can be found. These do not provide any information about the type and size of the buildings. In the reign of Henry III. from 1216 the relocation of the king's living quarters to the fortress grounds outside the White Tower finally began.

Heinrich III., Who is largely responsible for the present shape of the fortress, was only eleven times in the tower and stayed there for a total of 32 weeks. Seven of the eleven visits took place in 1261, when political crises repeatedly prompted him to seek refuge in the Tower. The other great tower builder, Edward I, came just as rarely. He was only in the tower six times in total. Like Heinrich before him, he preferred the more spacious Westminster and stayed mainly in the Tower when he wanted to show the exercise of power. Other kings, such as Johann Ohneland , used the tower much more often as living space, even if they contributed little to its expansion.

Edward I established the tradition that the king spent the night before his coronation in the tower. The English monarchs maintained this tradition for 300 years. During the crisis-ridden rule of Edward II, he repeatedly used the tower as a place of refuge. His son Edward III. did not consider this to be necessary any more and in the following centuries it was hardly used as a royal residence.

The shape and shape of the tower prevented renovations or additions that could have met the increasing royal demands on living space in the following centuries. In order to adapt the tower to the fashions of the time, larger parts of the building would have had to be demolished. It turned out to be significantly easier to build other palaces elsewhere. The last English king who voluntarily stayed at the Tower of London was Henry VIII when he stayed here for the coronation of his wife Anne Boleyn . He lived in the last apartment built in the Tower, which his father Henry VII had built. All subsequent kings and queens who stayed here no longer did so voluntarily. Anne Boleyn found herself just as involuntarily in the Tower a little later as the later Elizabeth I. Lady Jane Gray waited here for her execution after only nine days in reign.

Military facility (since 1078)

Fortress and barracks (since 1078)

The Tower served as a fortress designed to protect and control London. The central location on the Thames made it possible to repel attackers on London. But it was also a safe haven from which the King's troops could control London and its potentially troubled population. The tower was seldom the subject of siege . During the Wars of the Roses in 1460 allies of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York besieged the Tower and damaged its outer walls with artillery. But they did not succeed in taking the fortress.

On the occasions when attackers managed to get inside the fortress, this was due to the passivity of the fortress garrison. During the Peasants' Revolt with Wat Tyler , rebels managed to invade the tower without resistance in 1381. A crowd of around 20,000 had already stayed near the tower and threatened to storm the fortress if their demands were not met. Richard II , who was in the Tower, decided to pretend to accept demands and proposed negotiations in Mile End . When the gates opened to let the king and his entourage out, about 400 people stormed into the fortress with Wat Tyler, Jack Straw and John Ball . They searched and found Simon Sudbury , the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Chancellor of the Exchequer Robert Hales and his entourage. The rebels managed to get her out of the Tower and behead her on Tower Hill. The attackers looted the royal armory on this occasion. They destroyed archival materials and official documents that were kept in the tower. Since the documents handed down record shortly afterwards the replacement of the damaged lock on the treasury, it can be assumed that the insurgents also penetrated the treasury.

Shortly after the Kingdom of England introduced its first standing army after the English Civil War in 1661 , it began to permanently station troops in the Tower. There are 300 soldiers in the tower from 1661 who were permanently stationed there, but who later no longer appear in the sources. For the most part, troops were only temporarily stationed in the tower and had headquarters and barracks elsewhere. The uprising by James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, provoked new troops, which also created the 7th Foot The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers in 1685 . This was located in the tower and originally had the task of guarding the guns in the tower. Over the centuries it changed its structure several times and was incorporated into the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers in 1968 . This still has its headquarters and regimental museum in the tower.

In the early 19th century, the troops in the tower were reinforced. The French army under Napoleon Bonaparte threatened the English monarchy from the mainland. In its ongoing conflict over space in the Tower with the Board of Ordnance, Royal Mint and Archives, the British Army finally demanded decisive changes and in 1811 demanded a total of 929 soldiers stationed in the Tower, which could be increased to 1,700 men in an emergency. To do this, the Board of Ordnance would have had to vacate several buildings and hand over all stables to the Army. The standard of housing the soldiers would have been worse than in the regular barracks. The lack of space for the army was only helped by the construction of the Waterloo Barracks in the mid-19th century. Several hundred soldiers were stationed here until 1947.

Although the tower had not been attacked for centuries, the construction of Tower Bridge in 1893 provoked angry reactions from the army, who feared for the defensive ability of the tower. The crisis could not be resolved until the army was granted the right to occupy Tower Bridge as part of its duty. Until the 20th century, the tower was mainly used for counterinsurgency purposes. A permanent garrison was established in the Tower during the Commonwealth of England , when the then governor of the Tower stationed six to eight companies in the Tower. These soldiers would regularly move out in the centuries that followed when there were demonstrations or other insurgency-like situations in London. Under the conflict-ridden rule of James II , the king had mortars stationed on the two bastions to the north of the tower, whose obvious field of fire would have been the City of London. While the Chartists did not storm the Tower in the 19th century, contrary to the constable's expectations, the garrison located there moved out again at the beginning of the 20th century. Tower garrison members took part in the siege of Sidney Street in Stepney, London.

Arsenal, weapons store and weapons workshop (1078 to 2000)

From the late Middle Ages into the 20th century, the tower served as an arsenal and warehouse for armor and other weapons. It evolved from the king's wardrobe - that part of the royal household that was responsible for his personal possessions, including weapons. This has sat in the tower since the times of the Norman kings. Over the centuries the Wardrobe developed into the Board of Ordnance , which was responsible for all weapons and equipment of the English armed forces. It had its headquarters in the Tower of London until its dissolution in 1855.

During the Hundred Years War , supplies from all over England were collected in the tower and distributed from there to the fighting troops. The overwhelming success of the English longbow archers in the battles of war was due, among other things, to the stocks of arrows and bowstrings that were stored in the tower and were quickly available across the Thames.

Of the various users of the tower, the royal armory took up the most space until the middle of the 19th century. In the disputes of the 16th and 17th centuries, the tower was the king's most important weapons and ammunition depot. It was only with the rise of Great Britain to a world power that this role of the tower began to change. If the central and storage rooms of the tower were sufficient to be the most important warehouse in a civil war, they were by no means sufficient to equip a global imperial fleet. The conversion to firearms and explosives made the tower's location a problem: the mayor and council of London complained several times to the king that large quantities of explosives were being stored on the outskirts of the City of London. While the royal armory continued to play the dominant role in the Tower, the role of the fortress began to wane over other large warehouses and arms factories. In the centuries that followed, the tower continued to serve as an arms store and factory, but often for items and weapons for which there was no long-term storage facility and which were therefore housed in the easily accessible tower.

It was used as a makeshift arsenal until the 20th century. During the Second World War, the tower was primarily used to hold courses and train officers. In 1914, however, the British War Department had the earth backfilled in the Brass Mount Bastion removed so that 41,000 rifles could be stored there. The Brass Mount served as a weapons storage facility until the 1990s.

Map workshop (1683 to 1841)

The drawing room in the tower probably existed since 1683 as a storage room for cards. The Drawing Room in the Tower had existed as its own map workshop, which supplied the Army and Navy with new military maps, since 1717 with the two map-makers George Michelson and Thomas James. While Michelson was drawing maps, James was mostly busy making scale models of enemy fortresses. After Michselson's death in 1740, the model maker moved to the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich and the Tower concentrated on map drawing. In 1733 the workshop moved to larger rooms in the White Tower, as the number of employees presumably had increased. In 1752 the British lieutenant general introduced an organizational plan for 15 employees with clearly regulated hierarchies, working hours and salaries for the workshop, which had been run rather informally until then. In the various armed conflicts in which the crown was involved in the 18th century, the number of employees rarely fell below 30.

From 1790 onwards, numerous draftsmen traveled through the country in order to complete the Survey of Kent by 1801 . The cartographers finally left the Tower in 1841 when they moved to Southampton .

For a short time in the 17th century, John Flamsteed was able to set up his telescope in the northeastern Tourelle of the White Tower, which thus housed the first Royal Observatory .

Prison and execution site

Prison (1101 to 1941)

The tower served as a prison from 1101 to 1941. Until the 14th century, the tower served as a normal criminal prison for London and the surrounding regions. The direct connection to the English kings, the location on the water, the strong fortress walls against the possibly rebellious London population and the security by military troops turned out to be advantages for the imprisoned kings. Presumably at that time there was a separate prison building on the fortress area, which was later demolished. Newgate Prison , rebuilt in 1188, slowly replaced the Tower in this role. A prisoner breakout probably contributed to this, in which armed prisoners could run to the neighboring church All Hallows-by-the-Tower , the church bells rang, and an angry number of parts broke out of the gates and walls of the fortress.

After the 13th century, the tower's role as a regular prison came to an end. After that, it was mainly used to hold higher-ranking prisoners who were kept safe on the one hand, and housed appropriately on the other. In the daily life of the tower, and in the demands on the buildings, the prison function was a minor matter that hardly tied up resources. In the tower there were various English kings or ex-kings such as Richard II , Henry VI. , Eduard V. - one of the two princes in the Tower - as well as the "Nine Day Queen" Jane Gray . In the Tower, Henry VIII had two of his wives, Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard , executed. In addition, there were high-ranking prisoners of war, who were often ransomed for ransom: The Scottish kings John Balliol , David II and Jacob I were held in the tower, as was the French king John II.

In addition, the tower was repeatedly used to hold prisoners of war until the crown distributed them to other prisons. It started with hundreds of French prisoners in the Hundred Years War and didn't end until World War II, when German spies and angry submarine crews were smuggled through the tower. One of the last prisoners was Rudolf Hess , who was imprisoned in the Tower until May 20, 1941.

Due to the centuries of use as a prison, the buildings of the tower contain around 300 carvings, graffiti and other remains of the prisoners. Most of these inscriptions are limited to the names and initials of the prisoners - sometimes with a date added - but there are often more detailed and elaborate works on the walls. So graffiti representing the name of the prisoner graphically how Thomas Abbell that his name as A in a bell (english find bell recorded).

The next most common group are sayings or little wisdom. These are found in particular among prisoners who ended up in the Tower as part of the religious conflicts of the 16th and 17th centuries. These often refer to scriptures or other known Christian wisdom.

The most elaborate and elaborate work in the Tower was created in the 16th century by the Catholic clergyman Hugh Draper . He worked an astronomical clock in one of the walls of the tower, which has been preserved to this day.

Place of execution (1483 to 1941)

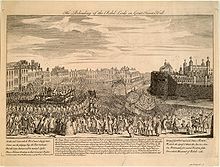

In general, the prisoners awaiting execution in the Tower were executed outside the gates of the fortress on Tower Hill. A total of seven executions took place in the Tower between 1483 and 1603. The first victim was William Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings , who stood between Richard, Duke of Gloucester and the English throne. Hastings was unexpectedly accused of high treason at a meeting in the White Tower, dragged onto Tower Green, and executed there after a few minutes. A few weeks later Richard was king. Henry VIII used the Tower to have his ex-wives and their confidants executed in private away from the general public. Henry's daughter Maria I had her rival to the throne, Jane Gray, beheaded on Tower Green, and Henry's other daughter, Elisabeth, had her former favorite Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, beheaded .

Anne Boleyn † May 19, 1536

Catherine Howard † February 13, 1542

Robert Devereux † February 25, 1601

The largest public execution on the Tower grounds took place in 1743. A total of 107 soldiers from the Scottish 43rd Regiment of Foot (the Black Watch ) were charged with mutiny and sentenced to death by a court of officers. Of these, 104 were pardoned and sent to the Mediterranean or America. Three, Samuel Macpherson, Malcolm Macpherson and Farquhar Shaw, were shot dead in front of their comrades on July 19 outside the Church of St. Peter ad Vincula . The riflemen came from the guard regiment on duty, which happened to consist of the Scots Guards .

After no further executions had taken place in the Tower or on Tower Hill for 150 years, World War I and World War II brought about a brief resurgence of executions on the Tower grounds. Eleven German spies were shot between 1914 and 1916. In 1941 Josef Jakobs , who was again executed by the Scots Guards , was also a German spy and the last person to be killed in the Tower. All spies were killed far less ceremonially than the victims of the 15th to 17th centuries. The shootings took place in a shooting range between Martin Tower and Constable Tower. This was removed in 1969.

Exhibition building

Menagerie (1235 to 1835)

From 1235 to October 1835, the Tower of London housed a menagerie of wildlife. Most of them were big cats and bears ; The animals kept there also included elephants , monkeys , rhinos and eagles , for example .

The tradition of keeping animals in the tower goes back to Heinrich III. back, who received three lions as a present from his brother-in-law on the occasion of the marriage of his sister Isabella to Emperor Friedrich II . The three big cats that Henry III. The tower that had just been extended did not survive long. In 1252 the tower housed a light-colored bear, this time a gift from the Norwegian king to Henry III. The successors of Henry III. continued the tradition of keeping animals in the tower. Lions were a traditional part of the menagerie.

From 1420 the animals in the menagerie in the tower could be viewed against payment of an entrance fee. The increasing interest in natural sciences from the 18th century had an impact on animal husbandry: the cages were modernized in the second half of the 18th century. They could now be heated.

Towards the end of the 18th century, the public's interest in the animals in the tower menagerie gradually waned. The number of animals and species kept in the menagerie steadily decreased until the crown hired Alfred Cops as the first experienced animal keeper in 1822. He found only an elephant, a few birds and the first grizzly shown in Great Britain as part of the royal menagerie. With the support of George IV , he began to rebuild the menagerie and to add a large number of new animal species. In 1829, in addition to the obligatory lions, tigers and bears, an ocelot , cheetah , caracal , various hyenas, zebras, llamas, parrots, anaconda and rattlesnakes could be seen. However, the renewed bloom of the tower menagerie lasted only a very short time. After the London Zoo opened, the animals were transferred to the zoo.

Tourist destination (since the 16th century)

Since the 16th century it has been possible to visit parts of the tower by prior arrangement. The first reports from travelers mainly referred to the Tower Menagerie and the " Line of Kings " - an exhibition of the figures of English kings on horse figures with real armor and weapons. The exhibition of the British Crown Jewels began when they moved to the Martin Tower in 1669. However, it was only open to the general public since the social reforms of the 19th century. Ticket sales in front of the tower have existed since the 19th century.

The first public written guide for the building was published in 1841, and was intended to replace various privately written guides that had been in circulation since the mid-18th century. In 1851 the first public ticket sales point was added to the tower. By 1900 the number of visitors was already half a million annually. Big attractions were the armories, the crown jewels, and the menagerie. In 2011, 2.55 million people visited the tower. After various free London museums, it was ranked seventh of the British tourist destinations and was the best-visited attraction that requires an entrance fee.

The Tower Ravens are closely connected to tourism . According to legend, these go back hundreds of years, but can only be historically proven when mass tourism began in the Tower. The first reliable sources of their existence appear at the end of the 19th century. A legend has been recorded since 1944, according to which the existence of the ravens for centuries has been linked to the welfare of the British Kingdom.

Museum (since around 1600)

The armories , the armory , have been part of the tower since its inception. Since the late Middle Ages, the pieces contained there have occasionally been shown informally to important visitors in order to impress them. After the Stuart Restoration , the Royal Armories developed into an organized exhibition open to the general public . The new kings recognized the propagandistic splendor that a new exhibition of national greatness would cast on them.

The Royal Armories Museum developed from three exhibitions. The Line of Kings featured historic British kings in their uniforms on horseback. This collection was a crowd puller, but historically not very authentic. When it was revised in the 19th century, the greatest exaggerations were erased, and public interest suddenly waned. In the Grand Storehouse , current weapons were presented in a spectacular exhibition until the building burned down in 1841. Finally, the Spanish Armories exhibition was designed to show the spoils of war from the victory over the Spanish Armada . Most of the objects presented, however, were older and came from the Tower's own holdings. Later, other own stocks, gifts and other spoils of war were added. The Royal Armories have been one of the main attractions of the Tower over the centuries. The particularly impressive showpieces include various armor from Henry VIII.

In the 1980s, the Royal Armories took the White Tower, the New Armories and part of the Waterloo Barracks. Since the 1990s, most of the Royal Armories' collections have been housed in a purpose-built museum in Leeds, Northern England . The exhibits in London continue to fill the lower two floors of the White Tower.

Since the 20th century, the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers has not only had its headquarters in the Tower, but also its own museum, the Fusilier Museum London . It arose from a private collection of objects important to its history, begun in 1949 by members of this infantry unit, which the regiment made public in 1962. The museum, like the headquarters, is located in the former officers' building of the Waterloo Barracks. The highlight of the collection are twelve Victoria crosses that were awarded to members of the regiment.

For a short time from 1981 to the 1990s, the Heralds' Museum was located in the Waterloo Barracks in the Tower. This museum of British heraldry displayed items from the College of Arms in particular . Now that the tower is managed by an independent organization, Historic Royal Palaces, there is no longer any space in the fortress for this museum. The Jewel House now occupies the entire ground floor of the Waterloo Barracks.

Mint (1279 to 1812)

The Royal Mint has its origins in the Tower. A mint had been in London since the 9th century. The exact location of this site is unknown. The first mentions of a specific location refer to the tower. Since Edward I had coins minted in the outer fortress ring of the tower, the Royal Mint has developed from this. A mint had been in the Tower since at least 1279. Although there have been attempts to centralize English coinage since the early Middle Ages, it was not until the 16th century that the Royal Mint achieved a de facto monopoly on coin production in the kingdom. In the early 19th century, the Royal Mint took up about a third of the entire tower area. Both the workshops in the tower and the living quarters of the craftsmen and officers involved in the production of coins were found.

Even during the short period of the English Republic , the London mint was minted. The lord protector Oliver Cromwell had the English silver crowns known as Cromwelltaler, which became particularly famous after his death, minted in London under the mint master Pierre Blondeau, which were associated with his posthumous execution.

It is not known where the Mint was in the Tower in the first centuries of its existence. However, it is likely that she occupied workshops and living quarters to the west of the outer fortress ring from the beginning to the end of her time in the Tower. The earliest archaeological finds on the Mint can be dated to the late 15th century. In the 16th century, the entire outer ring was known as The Mint . In contrast to the Board of Ordnance, which appropriated the tower, the Royal Mint always tried to maintain personal and organizational independence from the rest of the tower. The Mint area in the Tower was a separate area. Employees of the Mint were mostly there, the other Tower residents were not welcome inside the Mint.

Over the centuries the demand for new money increased and the amount of money to be minted increased. The coin in the tower was sufficient for everyday use in the following years, but the increased space requirement for more complicated processes for creating larger quantities of coins became evident. For space constraints, the Royal Mint moved from the Tower to the neighborhood in 1812, and in 1978 it moved entirely to Wales . Various buildings from the Mint have been preserved in Mint Lane to the west of the outer defensive ring. There is only a few archaeological evidence of the actual coinage.

Safe warehouse

Archive (13th century to 1858)

Since the late 13th century, the Tower has been one of the most important national archives in England and the United Kingdom. Documents are known from the year 1312 that deal with an already existing archive. Eduard II gave instructions to organize and sort the existing documents. In 1325 this task was completed. The documents were in different buildings over the centuries, and important collections were in the White Tower and the Wakefield Tower. The documents were also for a long time in archive buildings specially built for them.

The names of various Keepers of the Records are known from the Middle Ages. There are also documents that prove that the Tower handed over documents to the King and Parliament. These are strong indications for the existence of an organized archive in the Tower, but little is known about it from the Middle Ages. The first systematic attempts to organize the archive have come down to us from the time of Elizabeth I. At that time the documents were in the Wakefield Tower. The Keeper of the Records William Bowyer produced a multi-volume overview of the documents stored in the Tower, which they handed over to the Queen. As the correspondence of the English administration continued to increase after the Middle Ages, the archive spread over the entire tower area. Since the 16th century it has occupied numerous buildings that had previously served the king as a lounge or for military purposes. Much of the documents were in the Wakefield Tower, which was also the center of archival activities, throughout the early modern period. However, this was only accessible to archivists and researchers. Visitors who wanted to see “the archive” were normally shown the chapel in the White Tower, which was converted from a chapel into an archive building in the 17th century.

The archive was almost destroyed when the Ordonance Office burned down in 1788. Its building was right next to the Wakefield Tower. The tower and its contents only survived the fire because the wind drove the fire away from the Wakefield Tower. In the 19th century the English Parliament tried to amalgamate and modernize the various archives that existed in the United Kingdom. To this end, it united the various archives of the United Kingdom in the Public Record Office in 1858 . For this a building was built outside the tower. The fire in the Grand Storehouse in 1841 had also shown the danger in which the documents were. This was reinforced because at that time there were still large amounts of gunpowder in the White Tower, which also pose a threat to the archives. The new Public Record Office was located on Chancery Lane west of the city in the 19th century and has now been incorporated into the National Archives in the London borough of Kew .

Storage location of the crown jewels (since 1303)

The Crown Jewels have been kept in the Tower since 1303 after they were stolen from Westminster Abbey . The exact storage location in the tower changed several times over the centuries. Originally, the Keeper of the Jewels did not exhibit these pieces of jewelry in public. They were locked and kept as far away from the public as possible behind thick walls. The crown jewels are now the most popular tourist attraction within the tower.

The return of the Stuarts after the English Civil War awakened a regained monarchism. The public coronation of Charles II was enthusiastically received by parts of the London population. Since parliament destroyed the old crown jewels during the civil war, new jewels had to be made for this coronation. As the old Jewel House in the White Tower no longer existed, a new place for the crown jewels had to be found on the occasion of the restoration. These landed in the Martin Tower. The jewels were on the first floor, while the Keeper's apartment was on the first floor. Access to the Martin Tower was via the first floor.

The exhibition of the crown jewels began at this time. The exhibition was paid and an important source of income for the Masters of the Jewel House. At the beginning the demonstrations were informal. Guests were allowed into the room with the jewels. Then the Master of the Jewel House closed the door and retrieved the jewels from the closet where they were kept. After a few years this almost led to the theft of the crown, scepter and orb by Thomas Blood and an accomplice. After Blood's attempted theft, the monarchy systematized the exhibition. She had a list of the exhibits drawn up, built benches in the Martin Tower and a cage in which the jewels were kept. Visitors from this period describe the Martin Tower as a dark, narrow cave in which the jewels look like locked up. Nevertheless, the demand for the visitor attraction grew over the years.

When the Grand Storehouse burned down in the immediate vicinity of the Martin Tower in 1841, the Crown Jewels and the Martin Tower were briefly in danger. A newly built Jewel House next to the Martin Tower soon proved to be impractical and unsafe against theft or fire. Even so, the Jewel House remained in use for another 20 years, as none of the possible sites was ready to invest in a new building again. Only in the course of the major renovation work under Anthony Salvin did the crown jewels move into the Wakefield Tower in 1869 . The Jewel House has been located in the Waterloo Barracks since 1967 . The larger building can cope better with the flow of visitors. They were kept underground in the Waterloo Barracks until the 1990s. Since 1995 the exhibition has occupied the entire ground floor of the former barracks. A moving walkway transports the tourists past the pieces of jewelry.

Cemetery (since 1535)

Prisoners who were executed on Tower Hill outside the Tower or on Tower Green were often interred in the grounds of the Tower itself. Important prisoners of high social status were buried in often solemn funeral ceremonies at Westminster Abbey or St Paul's Cathedral . Prisoners who did not have this status were usually buried without any ceremony in the church of St Peter ad Vincula in the inner ring of the tower. This usually took place without the grave being marked.

In the 19th century, historian Lord Macaulay described the church as the saddest place on earth . Queen Victoria, at whose behest the tower was subject to major renovations in the 19th century, also complained about the condition of St. Peter ad Vincula. She ordered that all graves on the site be identified and restored. The Tower administration found the graves of Anne Boleyn († 1536), Catherine Howard († 1542), Jane Boleyn († 1542), Allen Apsley († 1630), Margaret Pole († 1541), Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset († 1551), John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland († 1553). The altar in the chapel was decorated with the coats of arms of those lying there. The chapel also contains the graves of Thomas More († 1535), John Fisher († 1535) and William Howard, 1st Viscount Stafford († 1680). A shrine where the faithful can pray has been a reminder of More since 1970.

Residents and rituals

Over the centuries, numerous and different groups of people who were related to the English or British monarchy lived in the Tower. In 2007 about 140 people lived in the area. These are the constable of the tower , the resident governor, the officers of the tower, the Yeoman warders and their families, the guards of the crown jewels, as well as a resident clergyman and a doctor.

Constable, Lieutenant and Resident Governor

The constable of the tower represents the king as commander in the tower in his absence. The post can be traced back almost completely to the year 1066. The position of constable was an important military and administrative position for many centuries, allowing control of the Pool of London and rule over the Tower Division east of London. The constable received duty on all luxury goods that came to London across the Thames. He owned the swans in the London Pool, all the debris that was there and all the teams and animals that had fallen from one of the London bridges. When the constable did not reside in the tower himself, the lieutenant of the tower took his place and exercised the constable's privileges. This division has been the rule since the reign of Elizabeth I. After the lieutenant had mostly not resided in the tower since the 18th century, the deputy lieutenant and a major took over its duties.

Often the constables came from the nobility or were high spiritual dignitaries. Several Archbishops of Canterbury also held the office. High officers, mostly generals who had retired from active service, have occupied this post since the 18th century. Since the 20th century, the positions of constable and lieutenant have primarily been ceremonial posts given to high officers after they have retired from active service. Since 1933 the office of constable has been awarded for five years. The constable's main privilege, which lasted into the 21st century, is direct access to the Queen of England. The current constable is General a. D. Nicholas Houghton .

The actual administration on site has been the responsibility of the Resident Governor of the Tower since the late 19th century. He is an active officer in the British Army and the Tower in Chief. His term of office is limited to five years. Since 1968 the office of Resident Governor has been linked to that of Keeper of the Jewel House .

Yeoman Warders and Guards

The Yeoman Warders under Chief Yeoman Warder are the police and law enforcement forces in the Tower. The group is about 30 to 40 strong and is responsible for guarding the gates and keeping order in the tower and on the tower wharf. Yeoman Warders were the only authorized guides in the Tower for a long time and are now best known as tourist guides. They are former officers and NCOs. They have been public service employees since 1952 and retire at the age of 65. They and their families have to live on the tower grounds.

The first mention of Yeoman Warders goes back to the 16th century in the reign of Henry VII. The prison guards in the tower were given the right to wear royal colors and to count themselves among the Yeomen of the Guard . The items were partially paid. Above all, however, the Warders lived on fees they collected from prisoners and tourists. The uniforms are supposed to imitate medieval uniforms, but date back to the 19th century. Since 2007, for the first time in history, a woman has been on the tower's security guards.

In addition to the Yeoman Warders, units of the regular army and guards from the Metropolitan Police guard the crown jewels. These come from one of the five regiments of the Guards Division . The delegation in the tower normally consists of an officer, five NCOs, a drummer and 15 soldiers. The army guards are provided by the same regiments that guard the other London palaces.

Ceremonies in the tower

The various ceremonies in the tower go back to the 19th century in their present form. Just as the architecture of the fortress was made medieval again during this period, the ceremonies were also more formalized and made more spectator-friendly. The uniforms of the servants in the tower go back to the 19th century as well as the exact sequence of the key ceremony or various other processes. In addition to the public ceremonies, the Tower celebrates the introduction of new Yeoman Warders or a new constable to the Tower. At the ceremony of lilies and roses, which has been taking place in Wakefield Tower since 1923, Eton College and King's College from Cambridge commemorate their founder Henry VI, who was presumably murdered in the tower.

Tower as part of the coronation celebrations

The Tower is closely linked to British history and the Crown in particular. He is considered one of the symbols of the United Kingdom and its history since the Middle Ages. In the Middle Ages and Tudor times, the British coronation ceremony began in the Tower. New Knights of the Bath , after a ritual cleansing, spent the night in the chapel in the White Tower. The next morning the king to be crowned knighted them, after which they accompanied the coronation procession from the Tower to Westminster Abbey.

Salute from the tower

Since Anne Boleyn's coronation in 1533, gun salutes from the tower have been guaranteed, and they still take place regularly. Of the longstanding traditions of the tower, this is the only one that can be traced back to the present day. Today, too, there are gun salutes on important monarchy occasions, such as the queen's birthday, the opening of parliament or state visits. Since the early 20th century, a total of 62 cannons have fired on monarchy events and 41 on state visits.

Historically, victories in battles were celebrated with gun salutes from the Tower. The last salute handed down in this way dates back to 1855, when the British conquered the city of Sevastopol in the Crimean War . In 1800 the Tower shot a salute on the occasion of the unification of Great Britain and Ireland and in 1894 on the occasion of the opening of Tower Bridge .

Originally fired from the small artillery unit located in the tower, the Honorable Artillery Company took on this task after it was disbanded in 1924 . This has existed under several names since 1537 and already provided the remaining artillery in the tower during the First World War.

Key ceremony

The most popular ceremony among tourists is the daily key ceremony . In the ritual, which has been taking place in this form since 1914, the Chief Warder, accompanied by regular soldiers, goes through the gates and guards of the tower between 9:53 p.m. and 10 p.m. and closes the gates. The basic form of the ceremony probably comes from the Tudor period, when prisoners were in the tower, who were often allowed to stay in the open areas such as the Tower Green. The exact design in its current form took place in the 19th century. The time the ceremony takes place at 10 p.m. has been fixed since 1914. Only at the time of World War II have there been any deviations since then. The London Blitz caused several shifts. At times there were no regular troops in the tower, so the ceremony took place without them. Today tourists can watch the key ceremony if they register in advance.

Beating the Bounds

The beating of the bounds , the pacing of the boundaries of the tower, goes back to the time when the tower and its surroundings were directly subordinate to the royal family and administratively did not belong to the city of London. The landmark hitting ceremony was intended to ensure that the boundary stones had not gone mad in the meantime. The main features of the ceremony were widespread in larger parts of England, but are now rarely performed. After the ceremony has been held every year on Ascension Day since the 17th century , it has only been held every third year since the 20th century. In addition, a group of Chief Yeoman Warder, the Vicar of the Tower, children of Tower residents and choirboys runs from Tower Millennium Pier over Tower Hill and Trinity Square to the former Iron Gate at what is now Tower Bridge. At each boundary stone, the children hit the boundary stone with sticks. Finally, the group sings the British national anthem on Tower Green. The ceremony largely follows the form that has been handed down from the 17th century.

Reception and research

Until the 19th century

The tower as a seemingly overpowering and terrifying structure inspired traditions and legends that ascribe the tower a longer past. Geoffrey von Monmouth , who only lived about 50 years after construction began, and numerous authors after him, dated the tower back to the times of the legendary English king Belinus , who is said to have lived well before the arrival of the Romans. The fort's timelessness and presence was evident in the Tudor period when people viewed the White Tower as a Roman fortress and called it Caesar's Tower .

As the fortress of the English kings opposite the city of London, the tower has always been a symbol of the rule of the English kings. The people of London and the residents of the Tower were in conflict for a long time. When, for example, the foundations of the fortress collapsed in 1240 when the fortress was being expanded, the people of London were evidently delighted and thanked the city saint of London, Thomas Beckett, for protecting them from unjustified exercise of royal power. Rebellions against the reigning monarch often sought the Tower as their target, and many of the King's visits to the Tower were primarily intended to demonstrate power. In the rebellions of Simon de Montfort as well as in the rebellion of Roger Mortimer and Isabelle , the City of London and the Tower played decisive roles. In both cases, the people and the City of London council clearly sided with the insurgents.

During the time of Elizabeth I and Jacob I , a total of 24 major dramas played in the tower. Although the tower is a center of royal exercise of power, it often represents an ambivalent symbol in the dramas of the time, which just as often shows the loss of power or the doubted power of the kings. In William Shakespeare's Henry VI. the king loses control of the tower. In the play The Life of Sir John Oldcastle by Anthony Munday is the basis for Tower traitor. The same piece also shows a successful escape from the fortress.

William Shakespeare used the Tower as a backdrop in some of his royal dramas about the Wars of the Roses . It appears particularly prominently as Cesar’s Tower in the play Richard II. The Tower also plays an important role in Shakespeare’s play Richard III. that popularized the story of the Princes in the Tower . In Richard III. the power of the king in the tower is untouched; but the monarch uses the fortress for activities of dubious moral value.

In particular, the function of the tower as a prison went down in cultural memory. Although the prison conditions there were mostly better than in the other prisons in London, the Tower is particularly associated with often gruesome stories from prison. In particular, the princes in the Tower brought to the stage by Shakespeare have entered the cultural memory. The reputation was reinforced by numerous Protestant and Catholic clergy who sat in the Tower during the wars of religion in the 16th century.

Since the 19th century

In the 19th century, the trend to see the Tower as a place of horror and prison, insidiousness and execution increased. John Everett Millais ' painting The Princes in the Tower was just as influential as Paul Delaroche's painting The Execution of Lady Jane Gray .

At the end of the 19th century, W. Harrison Ainsworth's horror novel The Tower was an influential bestseller. Even the opera The Yeomen of the Guard by Gilbert and Sullivan , published in 1888, is unusually serious and gloomy for the author duo. The English writer Edgar Wallace made the key ceremony a central point in an attempt to steal the crown jewels in his later filmed detective novel " The Traitors' Gate " .

In the 19th century, the public began to take a keen interest in the tower's history. 1821 appeared John Bayley's The History and Antiquaries of the Tower of London and 1830 Brayleys and Brittons Memoirs of the Tower of London . Both relied mainly on tradition and written documents. Scheduled archaeological exploration of the building did not begin until the 20th century. The first scheduled excavation took place in 1904 at the instigation of the Society of Antiquaries of London , which was looking south of the Wardrobe Tower for the former Roman city walls of London. In the following years, such work took place mainly in the course of renovations to the tower: 1914 in the northeast area near the Brass Mount, between 1934 and 1938 at the Byward Tower. In the course of the redesign of the entrance area, the researchers discovered larger remains of the Lion Tower and the former moat from the times of Edward I.

The tower as a symbol of English power and the English monarchy has been the target of political attacks on several occasions since it has been open to the public. As early as 1885, opponents of the English occupation of Ireland detonated a bomb in the White Tower. In 1974 an IRA bomb exploded in the collection of the Royal Armories in the White Tower.

Monument protection and endangerment

The tower is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is a Scheduled Monument in the United Kingdom. Almost every single building on the fortress site has its own listed building .

The UNESCO took the Tower on the World Heritage List because it fulfilled two criteria. According to criterion (ii), it was the model for numerous other castle complexes with stone keeps such as Colchester Castle , Rochester Castle , Hedingham Castle , Norwich Castle and Carisbrooke Castle . On the other hand, according to criterion (iv), it is an example par excellence for a castle in the Norman architectural style and an important reference point for military architecture of the Middle Ages.

Images of the Tower in London's cityscape have been popular since the Tudor era. The once dominant building forms the background of numerous London images. Over the centuries, the view from the other side of the river across from Traitors' Gate has proven to be particularly important. This allows a view of Traitors' Gate, the west and south facades of the White Tower up to the Waterloo Block. From this perspective, new buildings in the background are completely protected by White Tower. This view, and the clear sky in the background of the tower, is now protected by the London View Management Framework .

Historic Royal Palaces, as the manager of the tower, must be informed about every construction project within a radius of 800 meters as well as about construction projects further away that could significantly change the appearance of the tower. The organization considers the view from London's City Hall on the opposite bank of the Thames to be particularly important.

Nevertheless, the United Kingdom and UNESCO are in a dispute over the condition of the tower, as the newly towed skyline of numerous skyscrapers in East London significantly limits the effect of the tower from many perspectives. In a 2006 report, UNESCO complained that several construction projects in the vicinity of the tower could endanger its World Heritage status. These included the now-abandoned Minerva Building in the City of London and the 20 Fenchurch Street in the City of London, which was still under construction in 2012 . Since 2006, UNESCO has been calling for relevant studies by the World Heritage parties to ensure better protection of the tower.

literature

Overview literature

- John Whitcomb Bayley: The History and Antiquities of the Tower of London. London 1821 ( digitized ).

- Simon Bradley, Nikolaus Pevsner : London 1, The City of London . Penguin, London 1997, ISBN 978-0-300-09624-8 , pp. 354-371.

- John Britton and Edward Wedlake Brayley: Memoirs of the Tower of London. London 1830 ( digitized ).

- John Charlton (Ed.): The Tower of London. Its Buildings and Institutions. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1978, ISBN 0-11-670347-4 .

- Howard Montagu Colvin (Ed.): The History of the King's Works . Volume 2: The Middle Ages . Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1963, pp. 706-729.

- Howard Montagu Colvin (Ed.): The History of the King's Works. Volume 3: 1485-1660 (part 1) . Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1975, pp. 262-277.

- Brett Dolman, Susan Holmes, Edward Impey, Adrian Budge, Bridget Clifford, Jane Spooner: Experience the Tower of London , London 2013, ISBN 978-1-873993-01-9

- Geoffrey Parnell : English Heritage Book of the Tower of London . Batsford, London 1993, ISBN 0-7134-6864-5 .

- Geoffrey Parnell, Ivan Lapper: The Tower of London: A 2000 Year History. Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2001, ISBN 1-84176-170-2 .

Further information on individual aspects

- Christoper Edgar Challis: A New History of the Royal Mint. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1992, ISBN 0-521-24026-3 .

- Daniel Hahn: The Tower Menagerie. Simon & Schuster UK, London 2003, ISBN 0-7432-2081-1 .

- Brian A. Harrison: The Tower of London Prisoner Book: A Complete Chronology of the Persons Known to have been Detained at Their Majesties Pleasure, 1100-1941 . Trustees of the Royal Armories, London 2004, ISBN 0-948092-56-4 .

- Edward Impey (Ed.): The White Tower . Yale University Press, London 2008, ISBN 978-0-300-11293-1 .

- Simon Thurley: The Royal Lodgings at the Tower of London 1240-1320 . In: Architectural History. Vol. 38, 1995, pp. 36-57.

Web links

- Website at Historic Royal Palaces (English)

- Bibliography for Tower (English)

- A list of all monuments in and around the Tower (English)

- The Tower of London as a 3D model in SketchUp's 3D warehouse

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ivan Lapper, Geoffrey Parnell: The Tower of London. A 2000-Year History ( Landmarks in History ). Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2000, pp. 16-18.

- ^ A b c d John Steane: The archeology of medieval England and Wales Taylor & Francis, 1985, ISBN 0-7099-2385-6 , p. 9.

- ^ A b Anthony Sutcliffe : London: an architectural history Yale University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-300-11006-5 , p. 12.

- ^ A b Simon Thurley: Royal Lodgings at The Tower of London 1216-1327. In: Architectural History. Vol. 38, (1995) p. 37.

- ^ A b John Steane: The archeology of medieval England and Wales Taylor & Francis, 1985, ISBN 0-7099-2385-6 , p. 10.

- ↑ Simon Thurley: Royal Lodgings at The Tower of London from 1216 to 1327. In: Architectural History. Vol. 38, (1995) p. 39.

- ^ A b Simon Thurley: Royal Lodgings at The Tower of London 1216-1327. In: Architectural History. Vol. 38, (1995) p. 46

- ↑ Simon Thurley: Royal Lodgings at The Tower of London from 1216 to 1327. In: Architectural History. Vol. 38, (1995) p. 47.

- ^ A b c Anthony Emery: Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Southern England Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-521-58132-X , p. 245.

- ↑ Historic Royal Palaces: Tower of London World Heritage Site - Management Plan 2007. as pdf ( Memento of December 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) p. 24.

- ↑ Geoffrey Parnell: English Heritage Book of the Tower of London . Batsford, London 1993, ISBN 0-7134-6864-5 , p. 55.

- ^ A b c d Geoffrey Parnell: English Heritage Book of the Tower of London . Batsford, London 1993, ISBN 0-7134-6864-5 , p. 111.

- ↑ a b c Historic Royal Palaces: Tower of London World Heritage Site - Management Plan 2007. as pdf ( Memento of December 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) p. 30.

- ↑ a b c d Historic Royal Palaces: Tower of London World Heritage Site - Management Plan 2007. as pdf ( Memento of December 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) p. 12.

- ^ A b c d e Nigel R. Jones: Architecture of England, Scotland, and Wales Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005, ISBN 0-313-31850-6 , p. 290.

- ↑ a b Historic Royal Palaces: Tower of London World Heritage Site - Management Plan 2007. as pdf ( Memento of December 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) p. 31.

- ↑ Historic Royal Palaces: Tower of London World Heritage Site - Management Plan 2007. as pdf ( Memento of December 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) p. 32

- ↑ Geoffrey Parnell: English Heritage Book of the Tower of London . Batsford, London 1993, ISBN 0-7134-6864-5 , p. 115.

- ↑ a b C. Sabbioni et al: The Tower of London: a case study on stone damage in an urban area in C. Saiz-Jimenes (Ed.): Air Pollution and Cultural Heritage Taylor & Francis, 2004, ISBN 90-5809- 682-3 , p. 58.

- ↑ Historic Royal Palaces: Tower of London World Heritage Site - Management Plan 2007. as pdf ( Memento of December 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Derek Worthing, Stephen Bond: Managing built heritage: the role of cultural significance John Wiley & Sons, 2008, ISBN 978-1-4051-1978-8 , p. 40.

- ↑ Historic Royal Palaces: Tower of London World Heritage Site - Management Plan 2007. as pdf ( Memento of December 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) p. 43.

- ^ A b c Simon Bradley, Nikolas Pevsner: London 1, The city of London. Penguin, London 1997, ISBN 978-0-300-09624-8 , p. 359.

- ^ A b Simon Bradley, Nikolas Pevsner: London 1, The city of London. Penguin, London 1997, ISBN 978-0-300-09624-8 , p. 362.

- ^ A b c Simon Bradley, Nikolas Pevsner: London 1, The city of London. Penguin, London 1997, ISBN 978-0-300-09624-8 , p. 360.

- ^ Simon Bradley, Nikolas Pevsner: London 1, The city of London. Penguin, London 1997, ISBN 978-0-300-09624-8 , p. 363.

- ↑ a b c d Simon Bradley, Nikolaus Pevsner: London 1, The city of London, 1997, London: Penguin, ISBN 978-0-300-09624-8 , p. 367.

- ^ A b Nigel R. Jones: Architecture of England, Scotland, and Wales Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005, ISBN 0-313-31850-6 , p. 287.

- ↑ a b Abigail Wheatley: The Idea of the Castle in Medieval England Boydell & Brewer, 2004, ISBN 1-903153-14-X , p. 34.

- ^ Tower Liberties. In: Christopher Hibbert Ben Weinreb, John & Julia Keay (Eds.): The London Encyclopaedia. 3. Edition. Pan Macmillan, 2011, ISBN 978-0-230-73878-2 , p. 924.

- ↑ Simon Thurley: Royal Lodgings at The Tower of London 1216-1327. In: Architectural History. Vol. 38, (1995), p. 36.

- ↑ Geoffrey Parnell: English Heritage Book of the Tower of London . Batsford, London 1993, ISBN 0-7134-6864-5 , p. 52.

- ^ A b c Geoffrey Parnell: English Heritage Book of the Tower of London . Batsford, London 1993, ISBN 0-7134-6864-5 , p. 53.

- ^ Lindsey German, John Rees: A People's History of London Verso Books, 2012, ISBN 978-1-84467-855-6 , p. 35.

- ↑ WM Ormord: The Peasants' Revolt and the Government of England Journal of British Studies, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Jan. 1990), pp. 4-5.

- ^ A b W. Reid: The Tower and the Army in John Charlton (Ed.): The Tower of London. Its Buildings and Institutions. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1978, ISBN 0-11-670347-4 , p. 138.

- ^ A b c d W. Reid: The Tower and the Army in John Charlton (ed.): The Tower of London. Its Buildings and Institutions. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1978, ISBN 0-11-670347-4 , pp. 140-141.

- ^ W. Reid: The Tower and the Army in John Charlton (ed.): The Tower of London. Its Buildings and Institutions. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1978, ISBN 0-11-670347-4 , p. 142.

- ^ A b Geoffrey Parnell: English Heritage Book of the Tower of London . Batsford, London 1993, ISBN 0-7134-6864-5 , p. 116.

- ^ A b John Steane: The archeology of medieval England and Wales Taylor & Francis, 1985, ISBN 0-7099-2385-6 , p. 8.

- ^ A b John Steane: The archeology of medieval England and Wales Taylor & Francis, 1985, ISBN 0-7099-2385-6 , p. 11.

- ↑ Geoffrey Parnell: English Heritage Book of the Tower of London . Batsford, London 1993, ISBN 0-7134-6864-5 , p. 110.

- ^ A b Geoffrey Parnell: English Heritage Book of the Tower of London . Batsford, London 1993, ISBN 0-7134-6864-5 , p. 113.

- ^ Douglas W. Marshall: Military Maps of the Eighteenth-Century and the Tower of London Drawing Room Imago Mundi, Vol. 32, (1980), pp. 21-44, pp. 21.

- ^ Douglas W. Marshall: Military Maps of the Eighteenth-Century and the Tower of London Drawing Room Imago Mundi, Vol. 32, (1980), pp. 21-44, p. 23.

- ^ Douglas W. Marshall: Military Maps of the Eighteenth-Century and the Tower of London Drawing Room Imago Mundi, Vol. 32, (1980), pp. 21-44, pp. 27.

- ↑ Historic Royal Palaces: Tower of London World Heritage Site - Management Plan 2007. as pdf ( Memento of December 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Ruth Ahnert: Writing in the Tower of London during the Reformation, approx. 1530–1558. In: Huntington Library Quarterly. Vol. 72, no. 2, 2009, pp. 172-173.

- ↑ Ruth Ahnert: Writing in the Tower of London during the Reformation, approx. 1530–1558. In: Huntington Library Quarterly. Vol. 72, no. 2, 2009, p. 174.

- ↑ Geoffrey Parnell: English Heritage Book of the Tower of London . Batsford, London 1993, ISBN 0-7134-6864-5 , p. 118.

- ^ Daniel Hahn: The Tower Menagerie. Simon & Schuster UK, London 2003, ISBN 0-7432-2081-1 , p. 178.

- ^ Daniel Hahn: The Tower Menagerie. Simon & Schuster UK, London 2003, ISBN 0-7432-2081-1 , pp. 206-207.

- ^ Daniel Hahn: The Tower Menagerie. Simon & Schuster UK, London 2003, ISBN 0-7432-2081-1 , pp. 209-212.

- ↑ a b c Historic Royal Palaces: Tower of London World Heritage Site - Management Plan 2007. as pdf ( Memento of December 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) p. 81

- ↑ a b c d e f Geoffrey Parnell: English Heritage Book of the Tower of London . Batsford, London 1993, ISBN 0-7134-6864-5 , p. 112.

- ↑ ALVA: Visitor Statistics 2011

- ↑ Boria Sax: How Ravens Came to the Tower of London. In: Society and Animals. 15 (2007) pp. 269-283.

- ^ ACN Borg: The Museum: The history of the Armories as a showplace. In: John Charlton (ed.): The Tower of London. Its Buildings and Institutions. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1978, ISBN 0-11-670347-4 , p. 69.

- ↑ Historic Royal Palaces: The Fusilier Museum ( Memento from September 24, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ A b Sarah Barter: The Mint. In: John Charlton (ed.): The Tower of London. Its Buildings and Institutions. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1978, ISBN 0-11-670347-4 , p. 117.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica: London. 4th edition. London 1810.

- ↑ a b c Historic Royal Palaces: Tower of London World Heritage Site - Management Plan 2007. as pdf ( Memento of December 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) p. 74.

- ↑ a b c d A.CN Borg: The Record Office in John Charlton (ed.): The Tower of London. Its Buildings and Institutions. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1978, ISBN 0-11-670347-4 , p. 104.

- ↑ Geoffrey Parnell: English Heritage Book of the Tower of London . Batsford, London 1993, ISBN 0-7134-6864-5 , p. 109.

- ↑ MR Holmes: The Crown Jewels. In: John Charlton (ed.): The Tower of London. Its Buildings and Institutions. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1978, ISBN 0-11-670347-4 , p. 62.

- ↑ MR Holmes: The Crown Jewels. In: John Charlton (ed.): The Tower of London. Its Buildings and Institutions. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1978, ISBN 0-11-670347-4 , p. 63.

- ^ A b John Wittich: Catholic London. Gracewing Publishing, 1988, ISBN 0-85244-143-6 , p. 25.