Provisional Irish Republican Army

The so-called Provisional Irish Republican Army ( German Provisional Irish Republican Army ), in its own name simply Irish Republican Army , IRA for short , or Óglaigh na hÉireann ( Irish for volunteers of Ireland ) was a banned Irish Republican terror organization in the Republic of Ireland as well the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .

It saw itself as the direct and only legitimate continuation of the Irish Republican Army (the Army of the Irish Republic from 1916 / 1919-1922) , which fought for the independence of Ireland on the Easter Rising in 1916 and in the Irish War of Independence from 1919-1921.

The Provisional IRA was founded by Seán Mac Stíofáin , Ruairí , at the turn of the year 1969/70 at the beginning of the Northern Ireland conflict after a political-ideological split in the older Irish Republican Army , which arose after the War of Independence in 1922 and fought in the Irish Civil War (1922-1923) Ó Brádaigh , Dáithí Ó Conaill , Joe Cahill , Billy McKee , Seamus Twomey and others. The group was dissatisfied with the reformist Marxist leadership in Dublin, who appeared to prefer constitutional politics to armed struggle and had betrayed other essential Irish Republican principles for short-term political gain.

For its main goal of an independent, unified Ireland, it mainly used terrorist methods such as assassinations, bombings, hostage-taking and robbery in order to destroy the political system and the internal constitution of Northern Ireland as an integral part of British national territory. Other goals were to protect the Catholic nationalist minority from the Protestant Unionist majority and from the British security forces in Northern Ireland. In the course of the Northern Ireland conflict, it killed around 1,700 people in Northern Ireland, Great Britain , the Republic of Ireland and mainland Western Europe . In contrast, around 300 of their own members were killed. She was politically supported by her affiliated party Sinn Féin and support groups at home and abroad such as NORAID .

In 1997, after almost thirty years of struggle, the IRA announced a definitive ceasefire without having achieved its main objective of Irish reunification. On April 10, 1998, the parties to the conflict agreed on the Good Friday Agreement . On July 28, 2005, seven years later, the IRA leadership declared the end of the armed struggle: “All IRA units have been ordered to surrender their weapons. All IRA activists have been instructed to support the development of purely political and democratic initiatives through exclusively peaceful means. IRA activists are not allowed to take part in any other kind of action. ”This was followed by their complete disarmament or the destruction of their entire arsenal and in 2007 the recognition of the renamed Northern Irish Police PSNI .

IRA members and other Irish Republicans who disagreed with this development founded new militant groups with the so-called Continuity Irish Republican Army and Real Irish Republican Army (since 2012 New Irish Republican Army ), which are still engaged in armed struggle and thus today Detain terrorist methods for a united Ireland.

Established in 1969

The original IRA tried to reorient itself after the unsuccessful Border Campaign of the 1950s. Left-wing forces who wanted to give the organization a distinctly Marxist character now gained a strong influence . Instead of armed struggle, they saw the future in the political struggle and the reconciliation of Catholic and Protestant workers. The unrest in Northern Ireland, which escalated dramatically in the 1960s, took the IRA by surprise; as an armed movement it hardly existed at that time. It was now at a crossroads: Should one join the civil rights movement and advocate political equality for Catholics in Northern Ireland, or take up the armed struggle against the supremacy of British and Irish Unionists? Many pushed for violent guerrilla- style action ; Members with a traditionally Catholic nationalist background in particular were deeply suspicious of the Marxist ideology advocating a political solution. The break was finally led to the question of whether Sinn Féin as a political organization should abstain from the party systems in Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic ( abstentionism ), both of which were viewed as illegitimate by loyal Republicans.

The real reason, however, was the passive attitude of the Dublin leadership during the Northern Irish riots in the summer of 1969. At that time, Catholic-Republican residential areas, particularly in Belfast and Derry, were attacked by Protestant-Unionist militias. Many Northern Ireland Republicans believed that the Marxist IRA had abandoned the Catholic community by failing to prevent loyalists from attacking Catholic streets and burning their homes. The traditionalists and militarists accused the IRA leadership in Dublin of failing to bring in weapons, plans or personnel to defend the Catholic streets because of their purely political strategy. In addition, the British government had sent soldiers to Northern Ireland to protect the Catholics for the first time in decades, which the nationalist traditionalists in the IRA understood as an unbearable provocation that required a violent reaction. The Marxists within the left wing of the IRA, however, argued that tensions between Protestants and Catholics were deliberately provoked in order to pit workers of both denominations against each other. Violence is therefore only counterproductive to the solution of the Northern Ireland conflict.

In December 1969, therefore, the IRA split. The more nationalist-minded and more violent wing founded the Provisional IRA (short: Provos ), so named in reference to the declaration of the provisional government of the Easter Rising in 1916. The aim and task of this group was the armed guerrilla fight from the beginning . The more politically oriented left wing established the Official IRA , from which another actionist group, the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), split off in 1974 . Although there was also a split on the political level into Provisional Sinn Féin and Official Sinn Féin (later the Sinn Féin Workers Party or only Workers Party ), politics played no role in the early years of the Provos .

From the beginning there were feuds between the Provos and the Official IRA as both factions vied for control of the Catholic nationalist areas, especially in Belfast. However, because of their profile as the more reliable defenders of the Catholic community , the Provos quickly gained the upper hand.

organization

The IRA is organized hierarchically. At the head of the organization is the IRA Army Council, the chairman of which is the IRA Chief of Staff.

guide

All units of the IRA are authorized to send delegates to the IRA General Army Convention (GAC). This body is the supreme authority of the organization. Before 1969, the GACs met regularly. Because of an illegal organization's difficulty in keeping a meeting of so many members secret, there have only been three meetings since 1969 (1970, 1986, and 1997).

The GAC elects the twelve-person IRA Executive - nominally the Government of the Irish Republic of 1916. The Executive, in turn, elects the seven members that make up the IRA Army Council. This is the actual power center of the organization, which prescribes the political procedure and the strategic fundamental decisions as well as appoints the highest commanding officer, the chief of staff, from among its ranks or from outside the Army Council.

The chief of staff then appoints his deputy, the IRA Adjutant General, and occupies a headquarters (IRA General Headquarters; also GHQ), which consists of a number of individual departments. These departments are:

- IRA Quartermaster General (Quartermaster)

- IRA England Department (actions in England)

- IRA Overseas Department (Actions in Western Europe)

- IRA Department of Finance (Finance)

- IRA Department of Engineering (technical development)

- IRA Department of Training

- IRA Department of Intelligence (Reconnaissance)

- IRA Department of Publicity

- IRA Department of Operations (Head of Operations)

- IRA Department of Security (internal security service)

Regional command structures

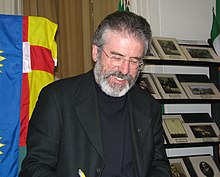

At the regional level, the IRA is divided into a Northern Command , which operated in the nine counties of Ulster and the five southern Irish counties on the border, and a Southern Command, which operated in the rest of Ireland. The Provisional IRA was initially commanded by an Army Council in Dublin . However, in 1977, parallel to the introduction of the cell structure at the local level, command of the “war zone” was transferred to the Northern Command. This reorganization, according to journalist and author Ed Moloney, was an idea of Ivor Bell, Gerry Adams and Brian Keenan .

The IRA Southern Command consisted of the Dublin Brigade and a number of smaller units in rural areas. These were mainly charged with storing and importing weapons for the northern units as well as raising money through bank robberies or the like. There were also organized units in Great Britain, Western Europe, and the United States.

Brigades

The IRA refers to its ordinary members as volunteers or óglaigh in Irish . Until the late 1970s, IRA volunteers were organized in units based on conventional military structures. Volunteers who lived in an area formed a company, which was usually part of a battalion. This in turn could be part of a brigade, although many battalions were not assigned to a brigade.

For most of its existence, the IRA had five areas in which there were brigades for what it called the “war zone”. These brigades were "stationed" in Belfast, Derry, Tyrone / Monaghan and Armagh. The Belfast Brigade had three battalions, specifically in the west, north and east of the city. In the early years of the Northern Ireland conflict, the IRA in Belfast developed rapidly. In August 1969 the Belfast Brigade had only 50 active members. At the end of 1971 it had 1,200 members; these gave it a large, but also more difficult to control structure. Derry City had one battalion and southern County Londonderry had a second. The Derry City Battalion became the Derry Brigade in 1972 because of a rapid surge in membership after Bloody Sunday (British paratroopers killed 14 unarmed protesters during an unauthorized civil rights march). County Armagh had three battalions. There were two very active battalions in South Armagh, making up the South Armagh Brigade , and a separate, less effective unit in North Armagh. The Tyrone / Monaghan Brigade, which also operated on both sides of the border and is often referred to simply as the East Tyrone Brigade , also frequently controlled units from County Londonderry and North Armagh. Fermanagh, South Down and North Antrim had units that were not assigned to any brigade or battalion. The command structures at battalion and company level were the same: both had their own commanders, quartermasters, and those responsible for explosives and reconnaissance. Sometimes there were those responsible for training or finances.

In the 1980s, the number of informants in the IRA increased significantly. The units in Derry and Belfast were particularly hard hit. While the Belfast Brigade was the most active of the four brigades in the 1970s, that changed in the 1980s and 1990s. Thus the rural IRA units from East Tyrone and South Armagh became increasingly important within the organization.

Active Service Units

In 1977 the IRA abolished the great conventional military organization principle, recognizing that it was vulnerable. Instead of the battalion structures, a system with two parallel types of units was used, some of which had been in use since 1974. The old company structures were used for tasks such as protecting nationalist areas, educating and hiding weapons. These were essential ancillary activities, but the main part of the actual attacks was now carried out by a second type of unit - the Active Service Unit (ASU). To ensure secrecy, the ASUs were small cells with usually five to eight members, which then carried out armed attacks. The ASUs' weapons were controlled by a quartermaster who was under the direct control of the IRA leadership. In the late 1980s and early 1990s it was estimated that the IRA had approximately 300 members in ASUs and approximately 450 more in supply units.

The exception to this reorganization was the South Armagh Brigade , which retained its traditional hierarchy and battalion structure and employed relatively large numbers of volunteers in its operations.

Provisional Fianna

The youth organization of the Provisional Irish Republican Army is called Provisional Fianna . The Fianna, whose name is derived from the Irish Fianna for warrior group , primarily served the recruitment of young people, but also had a supporting function for the activities of the IRA in the disputes of the 1960s and 1970s.

Strategy from 1969–1998

"Escalation, escalation, escalation"

The Provisional IRA's strategy at the beginning of the conflict consisted of three phases. In the first phase (1970), while the military arm was being established, the Provos concentrated on the defense of the Catholic-nationalist quarters in Northern Ireland, then in 1971 came the phase of "retaliation", in which the police and the British army " legitimate goals ”. In the third phase, the Republicans went on the offensive at all levels in the hope of a speedy end. In doing so, the IRA's strategy was to use as much force as possible to bring about a breakdown in the Northern Irish administration, while inflicting such great losses on the British armed forces that public opinion in London should be forced to withdraw from Ireland . This strategy was described by Sean MacStiofain as “escalation, escalation and escalation”. The model was the success of the Irish Republican Army in the Irish War of Independence from 1919 to 1921. "Victory 72" was the watchword. There was still optimism in the following year (“Victory 73”) and the next (“Victory 74”). However, these policies underestimated the Unionists' strong will to remain within the UK and risked that the armed struggle could not lead to a united Ireland but to a sectarian civil war.

At the time of the Irish War of Independence in the 1920s, Protestant loyalists had retaliated for IRA actions in the north with attacks on Catholic nationalists. To avoid this retaliation against the Catholic nationalist community in the future, the IRA did not take any action in urban centers of Northern Ireland during the Border Campaign in the 1950s. The Provisional IRA, however, no longer showed any inhibitions about carrying out such a campaign and accepted the risk of escalation and sectarian violence. This was one of the key differences between the Provos and the Official IRA .

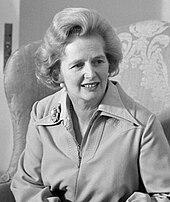

In 1972 the British government held secret talks with the IRA leadership in an attempt to enforce a compromise-based ceasefire in Northern Ireland, as support for the IRA and subsequent recruitment soared after the events of Bloody Sunday . The IRA agreed a temporary ceasefire from June 26 to July 9. In July 1972, IRA leaders Seán Mac Stíofáin, Dáithí Ó Conaill, Ivor Bell, Seamus Twomey, Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness met with a British delegation led by William Whitelaw . The IRA leaders, however, refused to agree to a solution that did not include an obligation to withdraw the British Army immediately (first to the barracks, then from Ireland) and the release of Republican prisoners. Irish independence should also be guaranteed. The British rejected these demands and broke off the talks.

Éire Nua and the 1975 Truce

The primary goal of the Provisionals during this period was the abolition of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland and their replacement by a new federal All-Ireland Republic with decentralized governments and parliaments for each of Ireland's four historic provinces. This program became known as Éire Nua - "New Ireland".

By the mid-1970s, most of those involved had realized that the IRA leadership's hopes for a quick military victory were becoming increasingly unfounded. More and more fighters and sympathizers were detained in Long Kesh and other prisons and camps. At the same time, the British military was just as unsure when it would finally achieve a resounding success against the IRA. At secret meetings between IRA leaders Ruairí Ó Brádaigh and Billy McKee with the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Merlyn Rees , the IRA guaranteed a ceasefire from February 1975 to January of the next year. The IRA initially believed this was the beginning of a long-term process that would ultimately lead to British withdrawal. But she quickly concluded that Rees was trying to take advantage of the disagreement within the movement and push the Provisionals to peaceful means without giving them any guarantees. Critics of the IRA leadership, particularly Gerry Adams' group, believed that the effects of the ceasefire on the IRA were catastrophic. Above all, they complained about infiltration by British informants, the arrests of many activists and the breakdown of discipline - the latter leading to sectarian killings and a feud with other Republicans of the Official IRA. The ceasefire broke out in January 1976.

The "Long War"

Thereafter, the IRA, under the leadership of Adams and his supporters, drafted the new strategy of the so-called "Long War" which it pursued for the remainder of the Northern Ireland conflict. It was a reorganization of the IRA in small cells that replaced the previous paramilitary structure. This was an admission that the campaign would have to go on for many years and that direct military confrontation would now increasingly be replaced by terrorism . In addition, it was decided to place greater emphasis on political activity through the Sinn Féin party . A Republican document from the early 1980s noted, “Both Sinn Féin and the IRA play different but converging roles in this war of national liberation. The Irish Republican Army is waging an armed campaign ... Sinn Féin maintains the war propaganda and is the public and political voice of the movement. ”The 1977 edition of the Greenbook , a handbook that was used to induce and train new recruits, lists the main points of the“ Tall War ":

- A war of attrition against enemy British Army forces based on causing as many deaths as possible, thereby creating public pressure on the [British] people at home for the government to consider withdrawing.

- A bombing campaign aimed at making the enemy's financial interest in our country unprofitable.

- To make the six counties ... ungovernable so that the enemy can only rule through repressive colonial-military rule.

- Sustaining the war and gaining support for its ends through national and international propaganda and public relations.

- Defending the war of liberation by punishing criminals, collaborators and informants.

Hunger strike and elections

The IRA prisoners who were sentenced after March 1976 no longer enjoyed special status and were treated like "normal" criminals in prison. In response, over 500 inmates refused to wash or wear prison clothes ( dirty protest and blanket protest ). These protests culminated in the second hunger strike in 1981 . Seven IRA and three INLA members starved themselves to death for recognition of their political status. A hunger striker ( Bobby Sands ) and anti-H-Bloc activist Owen Carron were elected to the British Parliament and two other prisoners on hunger strike in the Irish Dáil. There were also work stoppages and large demonstrations across Ireland to show sympathy for the hunger strikers. More than 100,000 people attended the funeral of Sands, the first hunger striker to die, in Belfast.

After the success of the IRA hunger strike in mobilizing support and winning parliamentary seats, Republicans invested increasingly more time and resources in elections after 1981. As a result, the Sinn Féin party gained more and more importance within the republican movement. Danny Morrison summed up this policy at a Sinn Féin Ard Fheis (annual meeting) that same year: "with the ballot in one hand and the Armalite in the other". In the early 1980s, the Éire Nua program was also rejected by the Provisionals under the leadership of Gerry Adams for the goal of a centralized Republic of Ireland.

"TUAS" - Peace Strategy

In the 1980s the IRA attempted to escalate the conflict with the so-called "Tet Offensive". When this failed, the Republican leaders increasingly sought a political compromise to end the conflict. From 1988, Gerry Adams met regularly for secret talks with John Hume , party leader of the moderate Social Democratic and Labor Party (SDLP). Secret talks were also held with British officials. After that, Adams increasingly tried to distance Sinn Féin from the IRA by claiming they were separate organizations and refusing to comment on IRA actions. Within the republican movement (IRA and Sinn Féin) the new strategy was described by the abbreviation TUAS (i.e. either "Tactical Use of Armed Struggle" (official) or "Totally Unarmed Strategy").

The IRA finally announced an indefinite ceasefire in 1994 on the condition that Sinn Féin be involved in the political talks for a solution. When this did not happen, the IRA terminated its ceasefire from February 1996 to July 1997. During this time she carried out several bomb attacks and shootings. After a renewed ceasefire, Sinn Féin was once again involved in the “peace process”, which ultimately resulted in the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

IRA member Seana Walsh, convicted of murder but later released from prison, published a video on July 28, 2005 with a statement by the IRA in which it declared the end of the armed struggle.

"The leadership of [the IRA] has formally ordered an end to the armed campaign. This will take effect from 4pm this afternoon.

All IRA units have been ordered to dump arms. All volunteers have been instructed to assist the development of purely political and democratic programs through exclusively peaceful means.

Volunteers must not engage in any other activities whatsoever. "

In its declaration, the IRA justified its fight as necessary because there had been pogroms against Catholics in the 1960s and 1970s . At the same time, the suffering on both sides of the conflict was recognized.

British Prime Minister Tony Blair called the statement "a previously unknown magnitude" and Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern called it a "huge and historic decision".

On the part of the DUP , the declaration was not further evaluated, except with the statement that there was a lack of an end to all “criminal activities”.

On August 22, 2015, George Hamilton, the head of the Police Service of Northern Ireland stated that the IRA still had an organizational infrastructure. The assumption that this dissolved with the 2005 declaration is wrong. He acknowledged, however, that the orientation of the group had changed significantly and that a peaceful policy was being pursued alone. However, individual members of the IRA are still involved in criminal activities or acts of violence, which, however, happen for purely personal reasons. With this in mind , the British Northern Ireland Minister Theresa Villiers set up a new monitoring body for compliance with the PIRA ceasefire in September 2015.

Examples of attacks

The following attacks occurred in the period from 1970 to 1997 (incomplete selection):

further activities

The IRA was funded primarily by an organization in the United States called the Irish Northern Aid Committee ( NORAID ). She also received help from the PLO in the form of weapons and training from Libya .

Separately from its armed campaign, the Provisional IRA was also active in other ways, such as fighting drug crime with the Direct Action Against Drugs group, "protecting" the nationalist areas in which they (especially parts of Belfast , Derry and rural areas South Armagh ) levied "taxes". Their opponents call this practice protection racket. But it is also legally active in the construction industry and gastronomy .

Attacks against other Republican paramilitaries

The IRA also had various feuds with other Republican paramilitary groups such as the Official IRA in the 1970s and the Irish People's Liberation Organization (IPLO) in the 1990s.

Joseph O'Connor, 26, was shot dead on October 11, 2000 in Ballymurphy, West Belfast. He was a senior member of the Real Irish Republican Army (RIRA). O'Connor's family and people associated with the RIRA claim that he was murdered by the Provisionals as a result of a feud between the two organizations, but Sinn Féin denied the allegations. To date, no one has been convicted or charged with this murder.

Organized crime raising money

The IRA has carried out many kidnappings and robberies of banks and post offices north and south of the Irish border during its 30-year history. During these actions, the IRA killed six gardaí and one Irish soldier .

According to the Irish Secretary of Defense from 2002 to 2007 Michael McDowell, the IRA was involved in organized crime on both sides of the Irish border. This includes smuggling counterfeit goods, cigarettes and diesel fuel .

Numerical strength

The number of Provisional IRA recruits may have been several thousand by the early to mid 1970s, but it fell sharply when the IRA reorganized in 1977. A 1986 RUC report estimated that the IRA had around 300 volunteers in Active Service Units and up to 750 active members across Northern Ireland. However, this estimate did not include the IRA units in the Republic of Ireland or those in Britain, continental Europe, or around the world. In 2005, then Irish Justice Minister Michael McDowell told the Dáil that the organization had "between 1,000 and 1,500" active members. According to the book The Provisional IRA (Eamon Mallie and Patrick Bishop), approximately 8,000 people joined the IRA in the first 20 years of its existence, many of whom left after prison sentences, "retired" or became disaffected. The exact number of those who joined the organization must therefore be even higher if one counts those who have been recruited since 1988. In recent times the strength of the IRA has been weakened somewhat, as members kept leaving the organization to join radical factions such as the Continuity IRA and the Real IRA . According to former Irish Attorney General Michael McDowell, each of these two organizations has little more than 150 members. Notwithstanding many of the successes of the British and Irish Army and Police Security Services in infiltrating the IRA, especially from 2001 onwards, the British, Irish and American governments believe that the IRA remains an extremely strong and capable terrorist organization.

P. O'Neill

The IRA traditionally uses a mysterious signature on its public announcements, all under the pseudonym "P. O'Neill "by the Irish Republican Publicity Bureau, Dublin".

According to Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, it was Seán Mac Stiofáin, Chief of Staff of the IRA, who came up with the name. The name was written or pronounced as the Irish orthography and pronunciation provides, ie “P. Ó Néill “. Ó Brádaigh also claims that the name has no special meaning. In doing so, he contradicts claims that see the name as a reference to Sir Phelim O'Neill , the executed leader of the Irish Rebellion of 1641 . After Danny Morrison , the pseudonym "S. O'Neill ”used during the IRA campaign of the 1940s.

Casualty numbers

The IRA has killed more people since the beginning of the Northern Ireland conflict than any other organization involved in it. However, members of the IRA have often denied that the organizations that opposed the IRA during the Troubles were separate and distinct. In the republican analyzes of the conflict, organizations such as the Ulster Defense Regiment (UDR), the British Army and RUC together with the UVF and UDA represented an alliance of the state and the paramilitary. So you have to add up their number of "murders".

Two very detailed studies of violent deaths during the Northern Ireland conflict, the University of Ulster's CAIN project and Lost Lives, differ slightly in the number of deaths by the Provisional IRA, but they both add up to approximately 1,800 deaths. Of these, about 1,100 were members of the Security Forces - British Army , Royal Ulster Constabulary and Ulster Defense Regiment. Between 600 and 650 were civilians. The rest are either loyalist or Republican paramilitaries (including over 100 IRA members who accidentally blew themselves up with their own bombs).

To date, not yet fully understood is the fate of the so-called " disappeared " ( "The Disappeared" , almost without exception Catholics) who were abducted by the IRA, killed and initially buried at an unknown location.

It is also estimated that the IRA injured 6,000 British Army, UDR and RUC men and up to 14,000 civilians during the conflict.

The IRA lost a little less than 300 volunteers in the Troubles. In addition, there are about 50 to 60 dead members of Sinn Féin .

Far more common than the killing of IRA volunteers was their arrest. Journalists Eamonn Mallie and Patrick Bishop estimate in their book The Provisional IRA that between eight and ten thousand members of the organization were in jail in the mid-1980s. That is a number that they also give for all former and then IRA members who have ever been in the IRA until then.

References

See also

- For history, see the general article on the IRA .

- Arms crisis

- Operation banner

- Internment Policy

- SAS (Special Air Service, a British special unit)

- Long Kesh

- Tiocfaidh ár lá

literature

- Martin Dillon: 25 Years of Terror - the IRA's War against the British.

- Richard English: Armed Struggle. A History of the IRA . MacMillan, London 2003, ISBN 1-4050-0108-9 .

- Peter Taylor: Provos - the IRA and Sinn Féin .

- Ed Moloney: The Secret History of the IRA . Penguin, London 2002.

- Eamonn Mallie and Patrick Bishop: The Provisional IRA . Corgi, London 1988. ISBN 0-552-13337-X .

- Toby Harnden: Bandit Country - The IRA and South Armagh . Hodder & Stoughton, London 1999, ISBN 0-340-71736-X .

- Brendan O'Brien: The Long War - The IRA and Sinn Féin . O'Brien Press, Dublin 1995, ISBN 0-86278-359-3 .

- Tim Pat Coogan: The Troubles .

- Tim Pat Coogan: The IRA: A History . 1994.

- Tony Geraghty: The Irish War .

- David McKitrick, Seamus Kelters, Brian Feeney, Chris Thornton, David McVea: Lost Lives .

- J Bowyer Bell: The Secret Army - The IRA . 3rd edition, 1997, ISBN 1-85371-813-0 .

- Christopher Andrews: The Mitrokhin Archive (also published as The Sword and the Shield ).

Web links

- CAIN (Conflict Archive Internet) Archive of IRA statements

- Official website of the Sinn Féin

- FAS Intelligence Resource Program - Irish Republican Army (IRA)

- Terrorism: Q&A Irish Republican Army

- Behind The Mask: The IRA & Sinn Fein PBS Frontline Documentation on the subject.

- Long interview with Martin Ingram, in which he describes his FRU activities on Radio Free Eireann (Attention, the interview starts after 25 minutes.)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Home Office - Proscribed Terror Groups ( Memento March 18, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) - Home Office Website, accessed May 11, 2007

- ↑ McDowell insists IRA will remain illegal. RTÉ , August 28, 2005, accessed May 18, 2007 .

- ^ Sutton data base of deaths: Organization Responsible for the death. Ulster University , accessed October 2, 2019 .

- ^ Sutton data base of deaths: Status of the person killed. Ulster University , accessed October 2, 2019 .

- ^ Full text: IRA statement. The Guardian , July 28, 2005, accessed March 17, 2007 .

- ↑ Kevin Cullen: Among IRA veterans, quiet acceptance of peace declaration. The Boston Globe , July 31, 2005, accessed October 24, 2007 .

- ^ Provos The IRA & Sinn Féin , pp. 77-78

- ↑ a b Brendan O'Brien: The Long War: The IRA and Sinn Féin . O'Brien Press, 1999, ISBN 0-86278-606-1 , pp. 158 .

- ^ English, pp. 114-115.

- ↑ English, p. 43.

- ↑ Moloney, pp. 155-160.

- ↑ a b O'Brien p. 158.

- ^ Moloney, p. 103.

- ↑ a b c O'Brien p. 161.

- ^ Bowyer Bell, p. 437.

- ^ Moloney, p. 377.

- ^ Conlon, Gerry (1990): In the name of the father, Bastei Lübbe paperback, p. 58 ff.

- ↑ Taylor p. 139.

- ↑ Peter Taylor: Brits . Bloomsbury Publishing , 2001, ISBN 0-7475-5806-X , pp. 184-185 .

- ^ Taylor, p. 156.

- ^ O'Brien p. 128.

- ↑ Quoted from O'Brien, p. 23.

- ^ O'Brien p. 127.

- ^ Moloney, p. 432.

-

↑ a b IRA orders end to armed campaign in: The Guardian, July 28, 2005, accessed on August 23, 2015

“The leadership [of the IRA] has ordered an end to the armed struggle. This order comes into effect at 4 a.m. this afternoon. All units of the IRA are ordered to lay down their arms. All volunteers have been instructed to support the development of a purely political and democratic program by exclusively peaceful means. The volunteers are not allowed to participate in any other activities of any kind. " - ↑ PSNI: Provisional IRA leadership did not sanction Kevin McGuigan murder in: The Guardian, August 22, 2015, accessed August 23, 2015

- ^ Henry McDonald: Government creates Northern Ireland ceasefire monitor after IRA claims. The Guardian, September 18, 2015, accessed on September 18, 2015 (English): "Villiers said: 'I am announcing today that the government has commissioned a factual assessment from the UK security agencies and the PSNI (Police Service of Northern Ireland) on the structure, role and purpose of paramilitary organizations in Northern Ireland. '"

- ^ Controversy over republican's murder. BBC , October 17, 2000, accessed March 17, 2007 .

- ↑ IRA denies murdering dissident. BBC , October 18, 2000, accessed March 17, 2007 .

- ^ Barry O'Kelly: McDowell takes stock. The Sunday Business Post , January 18, 2004, archived from the original on September 29, 2007 ; Retrieved March 9, 2007 .

- ↑ a b debates.oireachtas.ie , Vol. 605 No. 1 dated June 23, 2005

- ↑ a b Mallie, Bishop p. 12.

- ↑ a b Who is P O'Neill? - BBC News article, September 22, 2005.

- ↑ These allegations were particularly widespread after the Miami Showband massacre , the shoot-to-kill policy in Northern Ireland during the 1980s, the assassination of Pat Finucane, and the Brian Nelson / Force Research Unit controversy. After these episodes, Republicans claimed there was an overlap between loyalist paramilitaries and units of the British security services.

- ↑ Lost Lives (2004. Ed David McKitrick, Seamus Kelters, Brian Feeney, Chris Thornton, David McVea)

- ^ O'Brien p. 135.

- ↑ Lost Lives p. 1531.

- ↑ Quoted from O'Brien, Long War, p. 26.