Internment Policy

As Operation Demetrius measures are the Northern Ireland government under Brian Faulkner refer to operations where mainly from August 1971 Catholics or Republicans without trial interned were. The introduction of internment contributed significantly to the worsening of the Northern Ireland conflict.

Operation Demetrius

In August 1969, the British Army was first used to end the escalating conflict in the Northern Irish cities of Belfast and Derry . Regardless of the use of the army, the number of bombings, shootings and riots increased in the following years. The Provisional IRA , which was newly formed at the end of 1969, was held responsible for numerous attacks . Brian Faulkner took over the post of Prime Minister of Northern Ireland in March 1971. Faulkner was Northern Ireland's interior minister in the 1950s and was against the IRA's Border Campaign at the timewent to internment without trial. After initial hesitation, on August 5, 1971, the British government gave in to Faulkner's pressure to reinstate internment without trial. The legal basis was the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act (Northern Ireland) of 1922; a law that gave the judiciary and police special powers.

The internment began with an arrest operation known as Operation Demetrius by the British Army and the Royal Ulster Constabulary, Northern Irish Police, in the early hours of August 9, 1971. 342 people were arrested, mostly residents of Irish Catholic neighborhoods in Belfast and Derry. The internees were initially held in Belfast Crumlin Road Prison and on the HMS Maidstone , a prison ship moored in Belfast Harbor .

The arrest led to serious unrest, particularly in Belfast, in which 17 people died within 48 hours. Ten of them were Irish nationalists shot by the British Army. A focal point of the unrest was the Belfast district of Ballymurphy, where British paratroopers shot eleven people, including a Catholic priest, in the so-called Ballymurphy massacre in August 1971 . As a result of the unrest, an estimated 7,000 people fled from districts previously inhabited jointly by Catholics and Protestants. The majority of the refugees were Catholics, some of whom found refuge in the Republic of Ireland .

Of those detained on August 9, 104 had to be released after 48 hours for mistaken arrests. Since the selection of those to be interned was based on outdated and insufficient information, active members of the Provisional IRA were hardly affected. Instead, inactive IRA veterans, activists of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) and the People's Democracy party, which consists mainly of left-wing students, have been arrested for years . The IRA had been warned in advance of the arrest by an informant, so that many members were able to go into hiding. On August 13, 1971, senior IRA members held a press conference in Belfast at which Joe Cahill stated that there were only 30 active members of the IRA among the internees.

From January 1972 the internees were held in the Long Kesh and Magilligan camps near Derry. In particular, the Long Kesh camp, which was quickly established and reminiscent of the WWII prisoner of war camp , was perceived negatively by the Irish public; In some media reports, Long Kesh was compared to National Socialist concentration camps . Protestant loyalists were interned for the first time on February 5, 1973 . The last internees were released on December 5, 1975. A total of 1,981 people were interned; 1,874 of these were Republicans and 107 were Loyalists.

Shortly after internment was introduced, accusations were raised against the British security forces that the internees had been subjected to brutal treatment and that they were systematically tortured in order to extort information. At the center of the allegations were five interrogation methods ("five techniques"): Standing against the wall for hours with arms and legs apart, sleep deprivation, covering the head with a hood for days, deprivation of food and drink as well as psychological terror through noise ("white noise") ). A commission of inquiry set up by the British government came to the conclusion in November 1971 that there had been “in-depth interrogation” and, in individual cases, “ill-treatment” of internees; however, it was not systematic torture. The investigation report sparked significant protests, as a result of which the government of the Republic of Ireland and several civil rights organizations turned to the European Commission for Human Rights . After a process lasting several years, the commission described the interrogation methods in September 1976 as "torture" and "inhumane and degrading" treatment. The European Court of Human Rights rejected the torture allegation in January 1978, but upheld the allegation of inhuman treatment.

Political Consequences

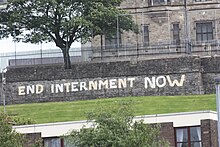

The introduction of internment had a significant impact on the further course of the Northern Ireland conflict and contributed to its worsening. Northern Ireland's Catholic minority saw the internment as a joint attempt by the government and the army to suppress the minority. The SDLP , founded in 1970 as a party of moderate Catholics, refused any political cooperation as long as the internment was ongoing. The civil rights organization NICRA launched a campaign of civil disobedience . Among other things, a rent strike was organized, in which up to a quarter of the Catholic households in Northern Ireland took part. In the Republic of Ireland there were numerous expressions of solidarity for the Northern Irish minority; Prime Minister Jack Lynch expressed his support for the passive resistance in Northern Ireland. The Provisional IRA was able to establish itself as the “protecting power” of the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland and considerably increase the number of its supporters. IRA-controlled no-go areas were created in Belfast and Derry . The security situation in Northern Ireland deteriorated considerably: eight people had been killed in the four months before the internment was introduced; 114 people died in the following four months.

Indirectly, the internments led to the dissolution of the Northern Irish government and to the direct administration of the province by the British government in March 1972: Before that, 13 demonstrators had been shot in Derry during a demonstration against the internments on January 30, 1972, the so-called Bloody Sunday .

Against the internments, the song Men behind the wire by Paddy McGuigan was directed , which topped the Irish charts for five weeks in 1972. McGuigan was later interned, believed to be in response to that song.

literature

- Johannes Kandel: The Northern Ireland Conflict. From its historical roots to the present. JHW Dietz successor, Bonn 2005, ISBN 3-8012-4153-X .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Tim Pat Coogan: The Troubles. Ireland's Ordeal 1966-1995 and the Search for Peace. Hutchinson, London 1995, ISBN 0-09-179146-4 , pp. 121-125.

-

↑ Prehistory: Kandel, Northern Ireland Conflict , pp. 139f.

Frank Otto: The Northern Ireland Conflict. Origin, course, perspectives. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-52806-6 , p. 99f. - ^ Edmund Compton: Report of the inquiry into allegations against the Security Forces of physical brutality in Northern Ireland arising out of events on the 9th August, 1971. HMSO, London 1971, ISBN 0-10-148230-2 . Online at CAIN - Conflict Archive on the Internet. (Accessed October 14, 2011).

- ↑ a b c Internment - A Chronology of the Main Events (Retrieved October 15, 2011).

- ↑ Kandel, Northern Ireland Conflict , pp. 140f.

- ↑ Otto, Northern Ireland Conflict , p. 100. Excerpt from the press conference on YouTube (accessed on October 15, 2011).

- ↑ Kandel, Northern Ireland Conflict , p. 141.

- ^ February 5, 1973 at CAIN - Conflict Archive on the Internet. (Accessed December 16, 2011).

- ↑ Kandel, Northern Ireland Conflict , pp. 141f.

- ^ Sabine Wichert: Bloody Sunday and the end of Unionist Government. In: Jürgen Elvert: Northern Ireland in the past and present / Northern Ireland - Past and Present. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-515-06102-9 , pp. 201-222, here p. 205.

- ↑ Kevin J. Kelley: The longest war. Northern Ireland and the IRA. 2nd edition, Lawrence Hill & Co, Westport 1988, ISBN 0-88208-149-7 , p. 158.

- ↑ Kandel, Northern Ireland Conflict , pp. 142ff.

- ^ Kelley, The longest war , p. 156.

- ↑ John McGuffin: Internment. Anvil Books, Tralee 1973. Online at irishresistancebooks.com.

Web links

- Internment (1971–1975) at Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN, English).