Civil disobedience

Civil disobedience (from the Latin civilis 'bourgeois'; hence also bourgeois disobedience ) is a form of political participation whose roots go back to antiquity. By means of a symbolic, conscientious and thus conscious violation of legal norms , the acting citizen aims to eliminate an injustice situation with an act of civil disobedience and thereby emphasizes his moral right to participation. The norms can manifest themselves through laws , obligations or even orders of a state or a unit in a state structure. The symbolic violation is intended to influence the formation of public opinion in order to eliminate the injustice. The disobedient consciously accepts to be punished for his actions on the basis of the applicable laws . He often claims a right to resistance , which, however, differs from a constitutionally given right of resistance . Those who practice civil disobedience are concerned with the enforcement of civil and human rights within the existing order, not with resistance aimed at replacing an existing structure of rule. However, the methods and forms of action of civil disobedience and resistance are in many cases the same.

The modern fathers of the concept are Henry David Thoreau , Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr. Since the publication of his article The Justification of Civil Disobedience, John Rawls ' reflections have played a central role in the philosophical discourse .

Theoretical foundations

Civil disobedience can only be practiced within the framework of a state unit. It presupposes legal norms that are enforced by a state or a government. A citizen who is subject to these norms can either accept them or partially or completely reject them. However, since legal norms are constitutive for every state, the only legally compliant possibility for the citizen would be to partially or completely withdraw from them, to give up citizenship and to leave the scope of the legal norms in question. Therefore, individuals who practice civil disobedience in a morally motivated manner cannot be expected to unconditionally accept the political system in which they are acting; it is sufficient for them to temporarily accept or accept the laws or the state as a whole.

With acts of civil disobedience, the disobedient intends to draw attention to individual laws or rules which he unselfishly perceives as unjust . With this kind of indication he wants to work towards a change. Civil disobedience then manifests itself either in a conscience-required violation of precisely those laws or rules that are assessed as unjust (direct civil disobedience) , or as a violation of just laws in order to publicly and symbolically point out the injustice of others (indirect civil disobedience) . The agent thus appeals to a higher right, be it divine right , natural law or right of reason , than the positive right given by law . Those who practice civil disobedience take the risk of being punished for their actions. It is controversial whether civil disobedience must be fundamentally non-violent, since the concept of non- violence depends on the definitions of violence used in each case . Instead, reference is often made to the symbolic meaning of acts of civil disobedience and the problem of violence is left out.

In terms of legal philosophy , the actor stands in the field of tension between the positive right given by legal norms , to which he is subject as a citizen , and justice norms to which he feels obliged by his conscience. In legal theory , theories of civil disobedience assume the existence of a divine right, a natural right or a right of reason that goes beyond positive law and is related to this in a justification context. The legal positivism other hand, deals exclusively with the positive law and denies the existence of such a parent, unwritten law. Under the assumption of a strict dualism of law and morality , civil disobedience in this legal-theoretical doctrine has a priori no special legal status that could be taken into account in case law.

Henry David Thoreau

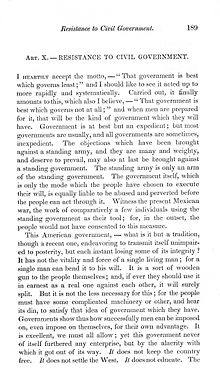

The expression civil disobedience (in English civil disobedience ) was coined by the American Henry David Thoreau in his essay Civil Disobedience , in which he explained why he no longer paid taxes in protest against the war against Mexico and slavery . Thoreau did not deal directly with civil disobedience, but with the conflicts of conscience that he had to resolve as a citizen , voter and taxpayer. Military service in war and the payment of taxes are Thoreau cases in which a citizen can conscientiously refuse to obey the state .

Proceeding from the view that governments are artificial structures that have the purpose of serving the interests of the people, his reflections on civil disobedience aim at a better government: “The lawful government [...] is always incomplete: namely, in order to be absolutely just it must have the authority and consent of the governed “Unjust laws and actions would have to be checked for legitimacy by honest citizens who feel obliged to a higher law than the constitution or that of the majority . These ideas build on the founding myth of the United States, which implies that individuals and groups can create justice against all odds , which is also reflected in the Federalist Papers of 1787/88. In these, Alexander Hamilton describes the individual as a fundamental element of any political unit. In the United States of the 1840s and 1850s, this understanding of politics led to all sorts of social and political experiments which, among others , took up some early socialist and some anarchist ideas. Colonies are exemplary here, based on the ideas of the utopian Charles Fourier and the anarchist Josiah Warren . Although Thoreau kept an intellectual distance from their concepts, he developed his own considerations in this overall context of social and political awakening. Thoreau argues that the political instrument of civil disobedience is to bring the law into conformity with what one's conscience dictates. As in the Federalist Papers, he describes the individual as a fundamentally shaping element of political units. But his statements also imply that laws must be respected as long as they are just. This results in the requirement of a - as Jürgen Habermas later calls it - qualified legal obedience to the individual citizen .

John Rawls and Jürgen Habermas

Based on Thoreau's founding of civil disobedience in the individual sense of justice , John Rawls and Jürgen Habermas describe acts of civil disobedience as calculated violations of rules of a symbolic character, which, through their illegality , are intended to indicate the urgency of the matter represented. The aim is to shake up the majority by appealing to their sense of justice and insight. Civil disobedience thus stands for "good reasons in the balance between legitimacy and legality". In order to have an effect as civil disobedience, the respective act must be morally justified and directed towards the public good. Actions that serve particular interests or even one's own, individual political or economic interests are therefore not designated as civil disobedience . After Rawls he will

“[...] exercised in situations where one expects arrest and punishment and accepts them without resistance. In this way, civil disobedience shows that it respects legal practice. Civil disobedience expresses disobedience to the law within the limits of legal compliance, and this feature helps create the impression in the eyes of the majority that it is really a matter of conviction and sincerity, which is actually what is involved their sense of justice is directed. "

For Habermas, too, civil disobedience must be morally justified and public in order to exclude members of society from exercising it for the sake of personal gain. Another factor contributing to this is that civil disobedience involves the violation of one or more legal norms and that this violation should be punished as illegal. It is only after the usual procedures in a democratic constitutional state have failed that civil disobedience can represent a last resort and is therefore not a normal political act. - Normally, the institutional possibilities to take action against decisions taken, for example by following the legal process, would have to be exhausted. However, cases are also conceivable in which the institutions have to be skipped and switched directly to the means of civil disobedience. For Habermas, the democratic constitutional state “[...] faces a paradoxical task: it must protect and keep up the mistrust against an injustice that occurs in legal forms, although it cannot take an institutionally secure form.” As for Thoreau, civil disobedience is for Habermas as an "element of a mature political culture" is an instrument for improving the state.

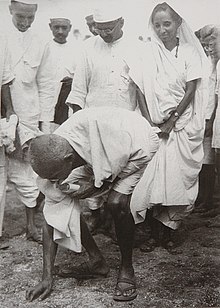

Gandhi's teaching of Satyagraha

At the beginning of the 20th century, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi developed his teaching of Satyagraha ( Sanskrit : सत्याग्रह satyāgraha) from an Indian tradition - not as a philosopher or theorist, but as an agent who has a concern. In this respect he stands in the tradition of Thoreau, albeit starting from a completely different starting point, which is based on the religious ideas of Hinduism and Jainism . Although he initially adopted the English term civil disobedience from Thoreau in order to explain his way of Satyagraha primarily to the English-speaking readers, he subsequently distances himself from Thoreau and explains that he pursues a broader concept:

“To say that I derived my idea of civil disobedience from Thoreau's writings is wrong. The opposition to the authorities in South Africa was well advanced before I received the essay ... When I saw the title of Thoreau's great essay, I began to use his expression to explain our struggle to English readers. However, I found that even civil disobedience did not convey the full meaning of the struggle. That's why I used the expression civil resistance . "

For Gandhi, civil disobedience is a method that works in a larger context. The strategy of Satyagraha is to appeal to the feelings and conscience of the respective addressee. Through Ahimsa ( Devanagari : अहिंसा , avoidance of violence , non-violence ), accompanied by the willingness to take pain and suffering on oneself ( love force or soul force ), Satyagraha wants to convince the opponent of the falseness of his action: “The goal of Satyagrahi is to convert the wrongdoer, not to subdue them. "

For the exercise of civil disobedience in the Indian struggle for independence , Gandhi makes it clear that without prior planning and a supplementary "constructive program" it is only daredevil, and that alone is worse than useless.

history

While Thoreau first described civil disobedience as a political instrument in 1849, by means of which citizens of a constituted state can point out injustices in the political process, approaches that describe the concept in concrete situations can already be proven several hundred years before our era. Many accounts from ancient times are either mythological in nature or it is not clear to what extent the historians of the time embellished actual events. These reports remain interesting because despite the lack of or controversial historical references, there is evidence that ideas and strategies comparable to concepts of civil disobedience after Thoreau first mentioned the term already existed in antiquity. Contrasting Thoreau's legal justification, a Christian tradition of civil disobedience, with reference to a divine right , traces its roots back to the Epistle to the Romans of the Apostle Paul ( Rom 13.1 EU ) and the Acts of the Apostles ( Acts 5.29 EU ): “One must obey God more because people. "

Since the concept was not yet theoretically founded before Thoreau, the examples listed below embed the theoretical developments since the 19th century and the forms of action from Thoreau to the present in a historical context. Civil disobedience is not a static concept; it was and is being practiced and developed as a social concept in different cultural and historical contexts with or without a dedicated philosophical reference. Therefore, for this form of social protest, even in the present, no complete agreement with theoretical approaches can be assumed.

Historical precursors

Bible

According to David Daube , the oldest written testimony to civil disobedience can be found in the Bible. In the Tanach , in Ex 1,15-17 EU , it is described how the Egyptian Pharaoh orders the Hebrew midwives to kill all newborn boys. This situation, in which the midwives refuse to carry out an ordered genocide , already fulfills the two main criteria of civil disobedience: it is non-violent, and the agents - in this case the midwives - invoke something higher in their fear of God than that of the ruler put positive right . The act of disobedience by the midwives towards the Pharaoh, however, remains recognizable only to the Hebrews, not to the ruler himself.

Early Christian concepts can be found in the Letter to the Romans of the Apostle Paul ( Rom 13.1 EU ) and in the Acts of the Apostles ( Acts 5.29 EU ). Here, too, divine law is placed above human law.

Greece

Prometheus

In Greek mythology, according to Hesiod (around 700 BC), the highest Olympian god Zeus refused fire to humans. The Titan Prometheus , who previously created humans, believes that humans have a right to use fire. Therefore he brings it to people and with this act opposes the divine right of Zeus. As a punishment, the immortal Prometheus in the Caucasus is tied to a rock and has to endure an eagle eating its liver every day until it is later freed by Heracles .

Antigone

In Sophocles ' tragedy Antigone (442 BC) the protagonist buries her brother Polynices against the orders of her uncle, King Creon . Here, too, a woman who feels committed to a higher law in her act non-violently, practices civil disobedience:

" Creon : And dared to violate my law?

Antigone : The one who announced this was not Zeus,

- Also Dike in the council of the dead gods

- Never gave such a law to people. So big

- Didn't your command seem to me, mortal

- That he has the unwritten God's commandments,

- The changeless, could surpass.

- They are not from today or yesterday

- They are always alive, nobody knows since when.

- [...] And I have to die, I knew that

- Even without your power of attorney. "

She is openly against the orders of her uncle, claims to have acted morally right and is ready to submit to the secular jurisprudence by Creon and to atone for her deed. It points out that this secular jurisprudence is not covered by divine law.

Lysistrata

The first description of a pacifist inspired sit-in is Aristophanes in his comedy Lysistrata (411 BC..): The women of Athens want the end of the Peloponnesian War force with Sparta by access to the Parthenon , the treasury Athens, by a kind of sit- in order to take away the material basis of the war. They exert additional private pressure on their husbands through mutually agreed sexual refusal. The subject of the Lysistrata gained importance in the peace movement in the second half of the 20th century, during which current events were artistically processed in film and theater productions using the name and strategies of Lysistrata.

According to Daube, the appearance of women in these very early cases is not a coincidence, but is based on the patriarchal structure of the respective societies, in which women had no legal participation in rule. In the first two cases described, two basic forms of civil disobedience emerge, on the one hand the passive refusal to obey instructions or orders, through inaction in the case of the ordered murder of the boys, and on the other hand through active and open resistance to Creon's orders Antigone. Antigone's disobedience comes closer to the modern conception of civil disobedience, as it - in addition to the criteria mentioned - draws the ruler's attention to his mistake, and thus gives him the opportunity to see his mistake, which he ultimately does not. With their sit-in, the Athenian women demonstrate a form of collective protest that is still widely used today. It is characteristic that the descriptions of all of these cases revolve around existential problems, life and death, that is, cases in which any delay as a result of observing the legal process has irreversible consequences. With this, disobedience is described as a last resort in accordance with modern conceptions.

Socrates

Plato makes Socrates in his Apology two cases describe in which he expressly opposes illegal commands, first under a democratic constitution, and later under the rule of the Thirty . As Prytan , he refuses to condemn ten generals during the Peloponnesian War (431 BC to 404 BC), contrary to the legal situation:

“And when the spokesmen were ready to arrest me and have me taken away […], I believed that I should rather expose myself to danger in alliance with law and justice than to stand on your side out of fear when the unjust decisions are made Prison and death. "

A few years later, under the rule of the Thirty (404-403 BC), he refused to carry out an order from the tyrants, with which they - according to Socrates - were trying to "entangle him in their debt" and left home without “doing anything wrong and indignant. [...] And maybe because of that I would have had to die if that government hadn't overturned shortly afterwards ”. As a public official, not just as a common citizen, Socrates refuses to carry out illegal orders in both cases.

Rome

By means of the secessio plebis , the march of the common people from the city, the plebeians of the city of Rome succeeded in 494 BC that the patricians granted them more rights in the Roman class struggles : They left the city of Rome and went to the Holy Mountain and declared that they would neither work nor fight until their demands were met. For the first time in history, the instrument of the general strike was used to enforce political and economic demands. With their action, the plebeians achieved, on the one hand, the appointment of two tribunes and three aediles as elected representatives to protect their interests, and on the other, they obtained a debt relief. Around 450/449 and 287 BC, two further secessiones plebis took place, which ultimately led to general legal certainty through the Twelve Tables and, as a result, to a significant improvement in the status of the plebeians.

The much rarer description of acts of civil disobedience by women in ancient Rome compared to Greece suggests, according to Daube, that the position of women there was different. This brings the focus of attention to two historical situations in which Roman women become active. - One in which they are threatened with a loss of status , and a second in which the normal course of authority for them initially fails: In 195 BC, the free women of Rome resisted a decree that would limit the financial expenses of women on clothing and Jewelry had been significantly limited several years earlier during the Second Punic War . They blocked the offices of two conservative tribunes until they gave up their resistance to the repeal of the decree. In the early period of cultural and economic growth, as Lucius Valerius argues on behalf of the Roman women, women feared that their husbands would be distracted from them by the better-dressed foreign women, while the men did not subject themselves to such dressing restrictions. In the rhetorical confrontation with Lucius Valerius , as Livius later reports, Cato tries unsuccessfully to expose the women's protests as self-interest, as an uproar and a damnable first step on the way to the demand for complete equality. While Cato assumes that women have revolutionary motives, Lucius Valerius explains the protest of the Roman women as a pragmatic demand for justice in a concrete situation that was felt to be unjust. Nonetheless, with the repeal of this law, a development began in which the women of Rome were increasingly granted rights, such as the right to freely dispose of their dowries.

In 42 BC, the triumvirs planned a special tax for wealthy women. This would have meant a significant change in the status quo, according to which women were not taxed. The women concerned first tried to exert influence through the wives of the triumvirs and thus overturn the special tax. When this path was unsuccessful, the women marched to the forum, as they had done 150 years earlier, and demanded to be allowed to present their concerns to the triumvirs. After they were initially supposed to be expelled by the lictors at the instigation of the triumvirs , their spokesperson, Hortensia , was given the opportunity to present their concerns the following day. She argued that women without official participation in political life should not be subject to tax. However, they did not accept the counter-argument of the triumvirs that women did not have to do military service and should compensate for this by paying a tax. In the end, Hortensia achieved a tax cut with her speech, supported by the women's demonstration.

Ciompi uprising in medieval Florence (Italy, 1378)

In the summer of 1378, under the leadership of Michele di Lando in Florence, the Ciompi , the woolen weavers - the wage workers in the Florentine clothing industry - rose against the prevailing order that had led to increasing poverty and dependence on their employers. It is characteristic of this uprising that in the second phase of the uprising, in July, the insurgents who were successful at the time completely renounced violence against people and looting. This is attributed to an ideology of justice, according to which this revolt should not serve personal enrichment, but justice in the sense of economic equality. This led to everything that was recognized as a luxury good - stately homes, furniture, jewelry - being destroyed and burned. As a result of this uprising, the Ciompi were temporarily granted their own guild. The Ciompi uprising can certainly not be classified as civil disobedience in its entire development. However, especially in July, the actions of those involved in this early industrial workers' uprising are at least partially comparable to modern ideas of civil disobedience due to the common goal of justice and the lack of violent actions against people. In contrast, the massive destruction of property, which goes well beyond symbolic gestures, is problematic for comparability with modern ideas of civil disobedience .

The Robert Ket Rebellion in Norfolk (England, 1549)

The tanner and landlord Robert Ket led a peasant rebellion in 1549 with around 15,000 rebels in the English county of Norfolk against the local landed gentry. During this time, clergy, landowners and nobility had increasingly begun to enclose previously freely accessible land to feed their sheep. In doing so, they not only opened up new land, but also often declared the local commons to be their private property. As part of the uprising, the enclosures were torn down, including those of Roberts Kets. What is remarkable about this uprising is that Ket forbade killing and looting, and that the demolition of the enclosures only happened after Ket had carefully judged it. The enclosure by the landowners was viewed by the rural population as theft. Ket made it clear through his jurisprudence that the aim of the uprising was to restore a lawful state of affairs.

Publication of Parliamentary Debates in the United Kingdom (1771)

After the publication of parliamentary debates had been banned in England under King Charles II in 1660 and this ban was renewed in 1723 and tightened in 1760, increasing resistance formed. From the mid-1760s onwards, London publishers suspected - motivated by publications by John Wilkes - an increased public interest in political reporting. In addition, there was increasing economic pressure due to increased competition in the newspaper market. The publication ban was deliberately violated by several newspapers. In 1771 two publishers - Robert Wheble of the Middlesex Journal and Roger Thompson of the Gazetteer - were arrested for this. When twelve other publishers were about to be arrested, the situation came to a head. Demonstrations ultimately achieved the release and change in practice. From 1774 Luke Hansard was allowed to publish the Journals of the House of Commons , the minutes of the House of Commons , verbatim. This was an important step in the British Enlightenment . The targeted violations of the law by the journalists made it possible to report openly and truthfully to parliament, which Edmund Burke , deploring a political culture of secrecy , had called for.

Henry David Thoreau (US, 1846)

In protest against slavery and the war against Mexico , Thoreau refused to pay his taxes and therefore spent July 23, 1846 in prison. This imprisonment motivated him to write On the Duty to Disobey the State , which later became the standard source. With this essay, he named the concept civil disobedience for the first time and inspired many subsequent theorists and practitioners of civil disobedience , such as Leo Tolstoy , Gandhi and Martin Luther King .

Gandhi and the Salt Marsh (India, 1930)

When Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi picked up salt on the beach of Dandi at the end of the salt march on April 6, 1930 , he symbolically broke the salt monopoly of the British colonial rulers . He had previously announced the action to the British Viceroy , Lord Irwin :

“If my letter does not touch your heart, on the eleventh day of this month I will continue to disregard the provisions of the Salt Laws with as many Ashram associates as possible. I consider this tax the most unfair of all from the point of view of the poor. Since the independence movement is essentially for the poorest in the country, a start is made with this evil. "

Gandhi moved with 78 of his followers, the Satyagrahi , on March 12, 1930 from his Sabarmati Ashram near Ahmedabad over 385 kilometers to the Arabian Sea to Dandi (Gujarat). After a 24-day march, he picked up a few grains of salt from the beach, symbolically breaking the British salt monopoly. The international press reported on the protest throughout the entire salt march, and tens of thousands of people lined the streets. After the salt march, many Indians followed his non-violent example and won salt by evaporating seawater and selling it on, some of it tax-free. As a result, around 50,000 Indians were arrested, including large parts of the leadership elite of the Indian National Congress . Ultimately, this protest led to the end of British colonial rule in India. In doing so, Gandhi's protests go beyond what is commonly referred to as civil disobedience . Gandhi himself had distanced himself from this term and saw his work as civil resistance . However, the methods that Gandhi used and developed in the protest actions are, in their non-violence, exemplary for protest actions of civil disobedience.

Civil disobedience during the National Socialist dictatorship (1933–1945)

The resistance of the Norwegian teachers (1942) and other comparable contexts of action are sometimes interpreted as acts of civil disobedience. However, since there are occupation situations here, only the instruments are comparable: the teachers practiced consistent non-cooperation with the occupying power, which was intended to make clear to them the lack of support for the occupation by the population. Thus the protest of the teachers is more comparable to the resistance of Gandhi, who wanted to free India from the colonial power Great Britain through his actions.

Official suspension of Aktion T4 after public protests (1941)

In 1940 and 1941 about 100,000 disabled and psychiatric patients were systematically murdered by SS doctors and nurses as part of Operation T4 . The euthanasia murders were justified by the ideas of eugenics that were exaggerated in the Nazi racial hygiene . For a long time, attempts were made to keep these killings secret by using only politically reliable medical personnel, cremating the murdered and issuing false death certificates. After the euthanasia became known, protests began by family members and by the Catholic Church - especially by the Münster bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen in his sermon on August 3, 1941 , in which he explained the meaning of the fifth commandment - "You shall not kill!" - stressed. As a result, the T4 campaign was officially discontinued, but then continued in hiding.

Demonstration in Berlin's Rosenstrasse (1943)

1945 documented Georg Zivier in from Helmut Kindler , Heinz Ullstein and Ruth Andreas-Friedrich published weekly magazine she protests from women in Berlin's Rosenstrasse. Between February 27 and March 6, 1943, they demonstrated their displeasure over the arrest and detention of their Jewish spouses in the administrative building of the Jewish community at Rosenstrasse 2-4 in Berlin-Mitte by the Gestapo :

“The secret state police had sorted out the" Arischversippten "from the huge assembly camps of the assembled Jewish population of Berlin and had them brought to a special camp on Rosenstrasse. It was completely unclear what would happen to them. Then the women intervened. [...] they appear en masse in front of the improvised prison. The police officers tried in vain to push the demonstrators - about 6,000 - away and divide them. Again and again they gathered [...] and demanded the release. Terrified by this incident [the Berlin control center made assurances to the Gestapo] and finally released the men. "

The aim of this week-long protest was to change a state-induced state of affairs that those affected found unbearable. Without attacking the National Socialist system as a whole, the demonstrators - according to other sources only about 200–600 at the same time - disregarded the ban on demonstrations that had been in force since 1933 and refused to obey the orders of the Gestapo. The spouses were released after the demonstration, and the Gestapo head of operations, Schindler, was transferred to a sentence.

Since, among other things, there are no records of the demonstrators' negotiations with the Gestapo, it has not been definitively clarified whether the release was due to the demonstration, whether the civil disobedience was the cause of the Gestapo's relenting, or whether the Gestapo's decision was for other reasons would have.

Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott (USA, 1955)

After Rosa Parks was arrested on December 1, 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama , for failing to vacate her seat for a white man during the period of racial segregation in the USA, the first day of a day followed on December 5, at the instigation of the local Women's Political Council Black boycotts of public buses. The Montgomery Improvement Association was founded under the direction of Martin Luther King , Jr., to organize peaceful protest against segregation by black people. The protest lasted 381 days. The boycott was lifted on December 20, 1956 after the United States Supreme Court upheld a similar ruling by the federal district court dated June 19, 1956 that racial segregation in schools and public transportation was unconstitutional. This protest finally helped the American civil rights movement break through.

Boycott of the Census (Federal Republic of Germany, 1987)

After several years of planning, a census was to take place in the Federal Republic of Germany in 1987 . Above all, this should provide statistical data for expanding the infrastructure . The census was originally supposed to take place in 1983, but after numerous protests it was finally prohibited due to a ruling by the Federal Constitutional Court . For a new count in 1987, the survey was partially redesigned on the basis of the Federal Constitutional Court ruling. The census opponents called for a boycott. The refusal to participate was justified by them as “civil disobedience for more democracy”. Depending on the region, around 15 percent of those surveyed refused to participate. As a consequence, the total census has been replaced by register surveys for the following surveys.

Social practice

The methods or forms of action used in civil disobedience are not synonymous with civil disobedience . As shown above, civil disobedience is based on an idea of justice derived from a higher law. Forms of action, on the other hand, are neutral in that they can also be used to enforce individual or group interests.

Forms of action

Theodor Ebert presents civil disobedience as an element in a matrix of forms of action:

| Escalation level | Subversive action | Constructive action |

| 1 | Protest ( demonstration , vigil , sit-in, ...) | functional demonstration ( teach-in , preparation of reports , ...) |

| 2 | Legal non-cooperation (e.g. election boycott , hunger strike , emigration , ...) | Legal role innovation (establishment of own educational institutions, publication of newspapers, ...) |

| 3 | civil disobedience (tax refusal, sit-ins, ...) | civil usurpation (formation of self-governing bodies, development of their own jurisdiction, ...) |

While the actors on the first escalation level do not intervene in the functioning of the system, actions on the second escalation level can paralyze the system without violating the law. Only at the highest escalation level are laws and regulations openly and non-violently disregarded. As a form of subversive action, civil disobedience means a symbolic ignoring of the authority of the state or the rulers. It lacks the constructive element that Gandhi called for in Constructive Programs . According to Theodor Ebert, the forms of action that are used within the framework of the instrument of civil disobedience include the open disregard of laws, for example through tax refusal, sit-in strikes, general strikes, occupying land or houses, and sit-ins in forbidden places.

Topics and actors

Civil disobedience can be exercised wherever the state influences the coexistence of its citizens and where there are morally justified doubts either about the intentions or about the expected or real consequences of this influence. This includes a diffuse spectrum, ranging from protests against racial segregation to the peace movement and anti-nuclear power movement to protests over data protection concerns.

Well-known examples of civil disobedience, which was reflected in political movements , were the Indian independence movement , the American civil rights movement (Civil Rights Movement) of the 1950s and 1960s, and since the mid-1970s the anti-nuclear power movement, the peace movement and the Monday demonstrations in 1989 in the GDR.

Well-known representatives of civil disobedience were Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi , Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King . In this tradition, many opponents of nuclear power , grassroots , peace demonstrators, pacifists , globalization critics and total objectors resist in the form of civil disobedience.

Notes on the legal evaluation

Civil disobedience as a political instrument stands between positive law that is violated and the goal of enforcing principles of justice for the community. In the event of a direct violation of a law, the injustice of which is to be pointed out by means of civil disobedience , the Radbruch formula formulated by the legal philosopher Gustav Radbruch offers jurisdiction under certain narrowly defined conditions the possibility of taking into account the motivation for the violation of the law. In doing so, it indirectly provides a justification for the practice of direct civil disobedience :

“The conflict between justice and legal certainty should be resolved in such a way that positive law, secured by statutes and power, has priority even if it is unfair and inexpedient in terms of content, unless the contradiction of positive law to Justice has reached such an unbearable level that the law as “wrong right” has to give way to justice. It is impossible to draw a clearer line between the cases of legal injustice and the laws still valid despite their incorrect content; but another demarcation can be made with all sharpness: where justice is not even striven for, where the equality, which constitutes the core of justice, was deliberately denied in the establishment of positive law, then the law is not just 'incorrect' law, rather, it lacks any legal nature at all. Because one cannot define law, including positive law, in any other way than an order and statute which, according to their meaning, is intended to serve justice. "

Germany

Civil disobedience as such is neither an administrative offense nor a criminal offense under German law. However, it expresses itself in actions that violate laws, ordinances or orders. This means that it is not civil disobedience that can be sanctioned, but the specific violation of the law, for example trespassing under §§ 123 f. StGB , threat according to § 241 StGB and damage to property according to §§ 303 ff. StGB. Disruptions in judicial processes can be subject to administrative penalties in accordance with procedural law.

Even if those who commit acts of civil disobedience emphasize the nonviolence of their actions , for example in the case of sit-downs or roadblocks , this can be assessed differently in the context of legal appraisals, as a different concept of violence is sometimes used and the assessed actions are analyzed differently from their respective intention . That is why - at least in German case law - for some actions that are attributed to civil disobedience by the participants, it is disputed whether they can still be viewed as nonviolent in the legal assessment; in the case of sit-down blockades, this question preoccupied the Federal Constitutional Court . The evaluation of an act as coercion subject to punishment according to § 240 StGB depends on this evaluation . A compulsion is not necessarily illegal as an open offense. The illegality must therefore be determined separately in the case law. “From § 152 of the StPO , whose addressees are the public prosecutor's office and the police , there is an obligation to prosecute. According to the law, there is no room for opportunity decisions by the police. ”There is no uniform case law here.

The situation is complicated from a legal perspective, as the term violence is used in the relevant criminal offenses of coercion, resistance to state violence ( § 111 , § 113 , § 114 StGB), dangerous interference in the railroad ( § 315 StGB) or Road traffic ( § 315b StGB), and the breach of the peace ( § 125 StGB) is defined differently.

While civil disobedience is only indirectly punished by sanctioning the violations of the norms committed, the motivation that is expressed in civil disobedience has consequences for the sentencing: According to Section 46 (2) StGB, motives, goals and attitudes must be taken into account in the sentencing; according to § 153 StPO, the proceedings can be discontinued "if the guilt of the perpetrator is to be regarded as minor" and no public interest in the prosecution can be assumed.

Austria

In Austria there is neither a right to civil disobedience nor a clearly defined sanctionable offense of civil disobedience . Violations of the law committed as part of civil disobedience are sanctioned. Under Austrian law, they can have consequences under civil law, criminal justice law, administrative criminal law and administrative procedural law.

Under civil law , the right of possession gives rise to the possibility of provisional injunctions, actions for disruption of possession (§§ 454ff. ZPO) and claims for damages or recourse claims (for example, according to § 896 ABGB). According to Section 344 of the Austrian Civil Code (ABGB), those affected can enforce residence bans through private coercion within the framework of self-help.

Under criminal law, individuals who commit civil disobedience run the risk of convictions resulting from the forms of action: coercion (Section 105 StGB), trespassing (Section 109 StGB), damage to property (Section 125 StGB), sabotage of military equipment (Section 260 StGB), resistance to state power (Section 269 StGB), violation of official notices (Section 273 StGB), blowing up a meeting (Section 284 StGB) and preventing or disrupting a meeting (Section 285 StGB) are possible offenses. In the event of coercion there are problems that result from the lack of a uniform definition of violence.

In terms of administrative criminal law , acting individuals are confronted with the problem that there is no general, codified administrative criminal law in Austria. The relevant provisions can be found in the administrative laws of the federal and state governments. For civil disobedience, facts of disorder , of "impetuous behavior", the violation of the assembly law or the violation of local or security police orders can become relevant.

In terms of procedural law, there are consequences from behavior in the courtroom. Disruptions to the negotiation can result in administrative fines.

Switzerland

In principle, the Swiss legal system provides neither a right to nor a criminal offense of civil disobedience . Actions that manifest civil disobedience are punished. According to Art. 47 of the Swiss Criminal Code (StGB), the court measures

“(1) [...] the punishment according to the culpability of the perpetrator. It takes into account previous life and personal circumstances as well as the effect of the sentence on the life of the offender.

(2) The culpability is determined according to the severity of the violation or endangerment of the legal interest concerned, according to the reprehensibility of the action, the motives and goals of the perpetrator and according to how far the perpetrator was able to endanger the internal and external circumstances or avoid injury. "

According to Art. 48 StGB, if the perpetrator acted "for reasons worthy of respect", the sentence can be mitigated. For this purpose, according to the highest court rulings, an ethically high or at least ethically justifiable attitude must be proven. Political motives are not worth paying attention to per se.

See also

- Public invitation to criminal offenses (Section 111 StGB)

literature

Text collections

- Hugo A. Bedau (Ed.): Civil Disobedience in focus. Routledge, London / New York 1991, ISBN 0-415-05055-3 .

- Andreas Braune (Ed.): Civil disobedience. Texts from Thoreau to Occupy. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-15-019446-1 .

- Peter Glotz (Ed.): Civil disobedience in the rule of law. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-518-11214-7 .

- Wolfgang Stock (Ed.): Civil disobedience in Austria. Böhlau, Vienna 1986, ISBN 3-205-05040-1 .

philosophy

- Hannah Arendt : Civil disobedience. In: At the moment. Political Essays (1943–1975). Rotbuch, Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-434-53037-1 .

- Juan Carlos Velasco Arroyo: Political Dissidence and Participatory Democracy. On the role of civil disobedience today (PDF; 222 kB). In: Archive for Legal and Social Philosophy. (ARSP). Volume 84, No. 1, 1998, pp. 87-104.

- Hugo A. Bedau: On Civil Disobedience. In: The Journal of Philosophy. Vol. 58, No. 21, 1961, pp. 653-661.

- Ronald Dworkin : Civil Disobedience. In: Ronald Dworkin: Civil rights taken seriously. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-518-28479-7 , pp. 337-363.

- Johan Galtung : Models for Peace. Methods and aim of peace research. Preface by Lutz Mez . Youth Service, Wuppertal 1972, ISBN 3-7795-7201-X .

- Mohandas K. Gandhi : Constructive Programs. Its Meaning and Place . Ahmedabad 2004, ISBN 81-7229-067-5 (first published 1941).

- Mahatma Gandhi: My life. Edited by CF Andrews. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-518-37453-2 .

- English first edition: Mahatma Gandhi: His Own Story. 1930.

- Jürgen Habermas : The new confusion. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-518-11321-6 .

- Jürgen Habermas: Law and violence - a German trauma. In: Jürgen Habermas: The new confusion. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-518-11321-6 , pp. 100-117.

- Jürgen Habermas: Disobedience with a sense of proportion. In: The time. September 23, 1983.

- Jürgen Habermas: Civil disobedience - test case for the democratic constitutional state. Against authoritarian legalism in the Federal Republic. In: Peter Glotz (Ed.): Civil disobedience in the rule of law. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1983, pp. 29-53. Reprinted in: Jürgen Habermas: The new confusion. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1985, pp. 79-99.

- John Rawls: The Justification of Civil Disobedience. In: John Rawls: Justice as Fairness. Karl Alber, Freiburg / Munich 1977, ISBN 3-495-47348-3 , pp. 165-191.

- English first edition: The Justification of Civil Disobedience. In: Hugo Adam Bedau (Ed.): Civil Disobedience: Theory and Practice. Pegasus Books, New York 1969, pp. 240-255.

- Henry David Thoreau: On the Duty to Disobey the State. Diogenes, Zurich 1967, ISBN 3-257-20063-3 .

- English first edition: The Resistance to Civil Government. In: aesthetic papers. Edited by Elizabeth P. Peabody . The Editor, Boston 1849.

- Leo Tolstoy : What should we do? 1991.

- Howard Zinn: Introduction (PDF; 115 kB). In: Henry David Thoreau: The Higher Law. Thoreau on Civil Disobedience and Reform. Edited by Wendell Glick. Princeton University Press, Princeton 2004, ISBN 0-691-11876-0 .

history

- Judith M. Brown: Gandhi and civil disobedience. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1977, ISBN 0-521-21279-0 .

- David Daube : Civil disobedience in antiquity. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 1972, ISBN 0-85224-231-X .

- Martin Humburg: Nonviolent Struggle. Historical and psychological aspects of selected actions from the Middle Ages and early modern times. MG Schmitz, Giessen 1984, ISBN 3-922272-25-8 .

- Hans-Heinrich Nolte : History of civil resistance. In: Hans-Heinrich Nolte, Wilhelm Nolte: Civil resistance and autonomous defense. Baden-Baden 1984, pp. 13-140; Nomos-Verlag, ISBN 3-7890-1038-3 .

- Arthur Kaufmann : On disobedience to the authorities. Aspects of the right of resistance from ancient tyranny to the injustice state of our time, from suffering obedience to civil disobedience in the modern constitutional state. Decker / Müller, Heidelberg 1991, ISBN 3-8226-1391-6 .

- Edward H. Madden: Civil disobedience and moral law in nineteenth-century American philosophy. University of Washington Press, Seattle 1968, ISBN 0-295-95070-6 .

- Jacques Semelin: Without weapons against Hitler. A study on civil resistance in Europe. Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-7638-0324-6 .

- Vishwanath T. Patil: Mahatma Gandhi and the civil disobedience movement. A study in the dynamics of the mass movement. Renaissance Publishing House, Delhi 1988, ISBN 81-85199-21-3 .

Politics, sociology, law

- Ralf Dreier : Right of Resistance and Civil Disobedience in the Rule of Law. In: Peter Glotz (Ed.): Civil disobedience in the rule of law. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-518-11214-7 , pp. 54-75.

- Theodor Ebert : Civil disobedience. Waldkircher Verlagsgesellschaft, Waldkirch 1984, ISBN 3-87885-056-5 .

- Nicolaus H. Fleisch: Civil disobedience or Is there a right to resistance in the Swiss constitutional state? Rüegger, Grüsch 1989, ISBN 3-7253-0359-2 .

- Hans Joachim Hirsch : criminal law and convicts. Lecture given to the Berlin Legal Society on March 13, 1996. de Gruyter, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-11-015542-7 ( Series of the Berlin Legal Society. Volume 147).

- Gernot Jochheim : The nonviolent action. Hamburg (Rasch and Röhring) 1984, ISBN 3-89136-004-5 .

- Martin Luther King : Call to Civil Disobedience. Econ 1993, ISBN 3-612-26036-7 (1st edition 1969; title of the original: The Trumpet of Conscience )

- Martin Luther King: I have a dream. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2003, ISBN 3-491-45025-X .

- Elisabeth Schnieder: Civil disobedience in Anglo-American law. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-631-45705-7 .

- Horst Schüler-Springorum : Criminal law aspects of civil disobedience. In: Peter Glotz (Ed.): Civil disobedience in the rule of law. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-518-11214-7 , pp. 76-98.

-

Gene Sharp : Politics of Nonviolent Action. 3 volumes, Sargent, Boston 1973.

- Volume 1: Power and Struggle. ISBN 0-87558-070-X .

- Volume 2: The Methods of Nonviolent Action. ISBN 0-87558-071-8 .

- Volume 3: The Dynamics of Nonviolent Action. ISBN 0-87558-072-6 .

- Norbert Kissel: Calls for disobedience and § 111 StGB. Fundamental rights influence in the determination of criminal injustice . 1996, ISBN 3-631-30661-X .

To its recent history

- Jürgen Bruhn: Worldwide Civil Disobedience: The Story of a Nonviolent Revolution. Tectum, 2018, ISBN 978-3-8288-4118-5 . (Chapter 6 deals with the peace movement and 7 with the protests against environmental destruction and predatory capitalism )

- Johan Galtung: The journey is the goal. Gandhi and the alternative movement. Peter Hammer Verlag, Wuppertal / Lünen 1987, ISBN 3-87294-346-4 .

- Johan Galtung: 50 Years: 100 Peace and Conflict Perspectives. Transcend University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-82-300-0439-5 .

Web links

- Civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance - Network Peace Cooperative

- Civil Disobedience in the 21st Century by Peter Nowak

- Sternstunde Philosophy: Demos, sit-ins, riots - where does civil disobedience end? Barbara Bleisch in conversation with Robin Celikates , SRF, October 13, 2019.

Central English-language web links:

- Kimberley Brownlee: Civil Disobedience. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Edward H. Madden: Civil Disobedience in the Dictionary of the History of Ideas

Individual evidence

- ↑ “In front of a Renaissance architecture on the left and a built-up hilly landscape, an image space created in perspective opens up like a stage under a wide, cloudy sky. The half-clothed Iusticia, the personification of justice, leans against a pillar - the symbol of power and strength. In front of her is a winged putto, who is holding out scales with his right hand and pointing with his left to a sword lying below the globe. However, Justice turns away from the signs of earthly justice and points to God the Father in heaven, the source of heavenly or divine justice. The tower on the right, adorned with trophies, which is to be interpreted as a symbol of earthly strength and justice, rests on a fragile foundation. " ( Source )

- ↑ Symbolically here usually means that nobody is allowed to suffer physical damage, nor that people are inflicted with greater material damage. For example, the British legal philosopher H. L. A. Hart assumes in a different context the existence of unambiguous principles of justice, "which limit the extent to which general social goals may be pursued at the expense of the individual." (H. L. A. Hart: Prolegomena zu einer theory of punishment . P. 75, in: H. L. A. Hart: law and morality , Göttingen (Vandenhoeck) 1971, pp 58-86). In other words, it means that harming others must be moderate .

- ↑ In the Federal Republic of Germany this right is laid down in Article 20, Paragraph 4 of the Basic Law (GG). According to Article 20, Paragraph 4 of the Basic Law , all Germans have the right to oppose all efforts aimed at eliminating the constitutional and democratic order if other remedies are not possible. See also: Dieter Hesselberger: The Basic Law. Bonn (BpB) 1988, p. 174f.

- ↑ Elke Steven: Civil disobedience. In: Ulrich Brand et al .: ABC of alternatives , Hamburg (VSA) 2007, p. 262f.

- ^ John Rawls: The Justification of Civil Disobedience. in: Hugo Adam Bedau (Ed.): Civil Disobedience: Theory and Practice , New York (Pegasus Books) 1969, pp. 240-255; German-language edition: John Rawls: The justification of civil disobedience. In: John Rawls: Justice as Fairness , Freiburg / Munich (Verlag Karl Alber) 1977, pp. 165–191.

- ↑ Jürgen Habermas and John Rawls , for example, make a further limitation , for whom civil disobedience can only be practiced in a democratic constitutional state, since the citizen is part of the sovereign. Following your argumentation, in a non-democratic system, resistance can only be exercised using non-violent methods.

- ↑ Cf. Edward H. Madden: Civil Disobedience ( Memento of the original from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. in: Dictionary of the History of Ideas , Vol. 1, p. 436.

- ↑ The legal theorist Ralf Dreier speaks of prima facie disobedience, since in the context of a legal assessment, the violation of the norm can later prove to be fundamentally justified. Cf. Dreier, Ralf: Right of Resistance and Civil Disobedience in the Rule of Law. P. 61, in: Glotz, Peter (Ed.): Ziviler Disobedience in the Rule of Law , Frankfurt am Main (Suhrkamp), 1983, pp. 54–75.

- ↑ Cf. Dreier, Ralf: Right of Resistance and Civil Disobedience in the Rule of Law. P. 62f.

- ↑ cf. the explanations of the theories and the legal evaluation below; Civil Disobedience ( Memento of the original from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Dictionary of the History of Ideas , Vol. 1, p. 436; Civil Disobedience . In: SEP.

- ↑ The Austrian legal philosopher Hans Kelsen, for example, describes justice as an illusion, as an irrational ideal that must therefore have nothing to do with a scientific conception of law. (See Hans Kelsen: Reine Rechtslehre. Aalen (Scientia) 1994, p. 1f; And: Hans Kelsen: Die Illusion der Gerechtigkeit , Vienna (MANZ'sche Verlagbuchhandlung) 1985.) The Briton Hart argues similarly. (Cf. H. L. A. Hart: Positivism and the separation of law and morality. P. 23, in: H. L. A. Hart: Recht und Moral , Göttingen (Vandenhoeck) 1971, pp. 14–57.)

- ↑ Published under this title since 1866, originally given in January 1848 as a lecture under the title On the Relation of the Individual to the State , first published under the title: Resistance to Civil Government (1849).

- ^ Zinn, Howard: Introduction. S. XIV, in: Thoreau, Henry David: The Higher Law: Thoreau on Civil Disobedience and Reform , ed. by Wendell Glick, Princeton (Princeton University Press) 2004.

- ↑ Thoreau, HD: On the duty to disobey the state. P. 34, in: Thoreau, H. D .: On the duty to disobey the state and other essays , Zurich (Diogenes) 1973, pp. 7–35.

- ^ Zinn, Howard: Introduction. S. XVIII.

- ↑ cf. Ostrom, Vincent: The Meaning of American Federalism. Constituting a Self-Governing Society. San Francisco (ICS Press) 1991, p. 6.

- ↑ See Walter E. Richartz: About Henry David Thoreau. P. 71ff, in: Thoreau, HD: On the duty to disobedience against the state and other essays , Zurich (Diogenes) 1973, pp. 71–83.

- ↑ Thoreau, HD: On the duty to disobey the state. P. 8f.

- ^ Habermas, Jürgen: Law and violence - a German trauma. In: Habermas, Jürgen: The new confusion , Frankfurt am Main (Suhrkamp) 1987, pp. 100–117.

- ↑ Habermas, Jürgen: Civil disobedience - test case for the democratic constitutional state. P. 33f, in: Peter Glotz (Ed.): Civil disobedience in the rule of law , Frankfurt am Main (Suhrkamp) 1983, pp. 29–53.

- ↑ Habermas, Jürgen: Civil disobedience - test case for the democratic constitutional state. P. 51.

- ↑ John Rawls: The Justification of Civil Disobedience. S. 177, in: Rawls, John: Gerechtigkeit als Fairness , Freiburg (Alber) 1976, pp. 165–191.

- ↑ For Rawls and Habermas, civil disobedience can only be practiced in a democratic constitutional state, since the citizen is part of the sovereign here. In other systems, accordingly, resistance can only be exercised using nonviolent methods.

- ↑ Habermas, Jürgen: Civil disobedience - test case for the democratic constitutional state. P. 32ff.

- ↑ Habermas, Jürgen: Disobedience with a sense of proportion. In: DIE ZEIT, 23/09/83.

- ↑ cf. Gandhi, MK: For Passive Resisters. In: Indian Opinion , October 26, 1907.

- ↑ orig .: The statement that I had derived my idea of Civil Disobedience from the writings of Thoreau is wrong. The resistance to authority in South Africa was well advanced before I got the essay… When I saw the title of Thoreau's great essay, I began to use his phrase to explain our struggle to the English readers. But I found that even 'Civil Disobedience' failed to convey the full meaning of the struggle. I therefore adopted the phrase 'Civil Resistance.' from: Letter to P. K. Rao, Servants of India Society, September 10, 1935, quoted in: Louis Fischer: The Life of Mahatma Gandhi , London (HarperCollins) 1997, pp. 87-88.

- ^ "The Satyagrahi's object is to convert, not to coerce, the wrong-doer." Gandhi, M. K .: Requisite Qualifications. In: Harijan , March 25, 1939.

- ^ Mohandas K. Gandhi: Constructive Program. It's Meaning and Place , Ahmedabad 1941.

- ↑ Cf. Theodor Ebert: Tradition and Perspectives of Christian Disobedience. S. 218, in: Theodor Ebert: Ziviler Disobedience. From the APO to the Peace Movement , Waldkirch (Waldkircher Verlagsgesellschaft) 1984, pp. 217–235.

- ^ Daube, David: Civil Disobedience in Antiquity. Edinborough (Edinborough University Press) 1972, p. 5.

- ↑ In his act Prometheus again subordinates the divine right of Zeus to a right of reason.

- ↑ cf. Daube, David: Civil Disobedience in Antiquity. P. 60.

- ^ Sophocles: Antigone. 449-461.

- ↑ See: Edward H. Madden: Civil Disobedience ( Memento of the original from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. in: Dictionary of the History of Ideas , Vol. 1, p. 435.

- ^ Aristophanes: Lysistrate ; see. also: Edward H. Madden: Civil Disobedience ( Memento of the original from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. in: Dictionary of the History of Ideas , Vol. 1, p. 435.

- ↑ cf. Daube, David: Civil Disobedience in Antiquity. P. 5ff.

- ↑ Plato: Apology. Cape. 20; (quoted from the Reclam translation by Kurt Hildebrandt).

- ↑ Plato: Apology. Cape. 20th

- ^ Daube, David: Civil Disobedience in Antiquity. P. 73ff.

- ↑ See Alföldy, Géza: Römische Sozialgeschichte. Wiesbaden (Steiner) 1984, pp. 23-26; and Will Durant : Kulturgeschichte der Menschheit , Volume 4, Cologne (Naumann and Göbel) 1977 (?), pp. 40f.

- ^ Livy, XXXIV.

- ^ Daube, David: Civil Disobedience in Antiquity. P. 27ff.

- ↑ cf. also Will Durant : Kulturgeschichte der Menschheit , Volume 4, Cologne (Naumann and Göbel) 1977 (?), p. 107f.

- ↑ With this argument she anticipated the slogan of the American independence movement “ No taxation without representation ” .

- ↑ Valerius Maximus 8.3.3 ; see. Daube, David: Civil Disobedience in Antiquity. P. 29ff.

- ↑ cf. Piper, Ernst: The uprising of the Ciompi, Pendo Verlag 2000; Humburg, Martin: Nonviolent Struggle. Historical and psychological aspects of selected actions from the Middle Ages and early modern times, Gießen (M. G. Schmitz Verlag) 1984, pp. 35–40.

- ^ Humburg, Martin: Nonviolent Struggle. Historical and psychological aspects of selected actions from the Middle Ages and early modern times, Gießen (M. G. Schmitz Verlag) 1984, p. 62f; Robert Ket and the Norfolk Rising (1549) . For a detailed description cf. also the article Kett's Rebellion in the English Wikipedia.

- ↑ Patrick Bullard: Parliamentary rhetoric, enlightenment and the politics of secrecy: the printers' crisis of March 1771. In: History of European Ideas 31 (2005) 313-325; See also: Theodor Ebert: Civil disobedience in parliamentary democracies. S. 114, in: Martin Stöhr (Ed.): Civil disobedience and constitutional democracy , Arnoldshainer Texte, Volume 43, Frankfurt am Main (Haag + Herchen) 1986, pp. 101-133.

- ↑ King wrote in his autobiography (chapter 2) that he first learned about nonviolent resistance in 1944, at the beginning of his time at Morehouse College , by reading 'On Civil Disobedience'

- ↑ see also English Wikipedia

- ↑ orig. If my letter makes no appeal to your heart, on the eleventh day of this month I shall proceed with such co-workers of the Ashram as I can take, to disregard the provisions of the Salt Laws. I regard this tax to be the most iniquitous of all from the poor man's standpoint. As the Independence movement is essentially for the poorest in the land, the beginning will be made with this evil. In: Gandhi's letter to Irwin. Gandhi & Dalton, 1996, p. 78.

- ^ Letter to PK Rao, Servants of India Society, September 10, 1935, quoted in: Louis Fischer: The Life of Mahatma Gandhi , London (HarperCollins) 1997, pp. 87-88.

- ^ Gernot Jochheim : The non-violent action , Hamburg (Rasch and Röhring) 1984, p. 264f.

- ^ Ernst Klee : "Euthanasia" in the Nazi state: The "Destruction of life unworthy of life." Frankfurt am Main (Fischer) 1983, p. 333 ff.

- ↑ Documentary essay uprising of women by Georg Zivier in them , No. 2, December 1945, pp. 1-2; quoted from: Heinz Ullstein: Playground of my life , Munich (Kindler) 1961, p. 340.

- ↑ On the problem of the number cf. Myth and reality of the “factory action ” and resistance against Rosenstrasse (In Chapter 4 The Protest and the Consequences (pp. 139–189)…) .

- ^ Ordinance of the Reich President for the Protection of the German People of February 4, 1933 , in: Reichsgesetzblatt Part I, February 6, 1933.

- ↑ Cf. Nathan Stoltzfus: Resistance of the Heart. The uprising of the Berlin women in Rosenstrasse - 1943. Munich (Hanser) 1999.

- ↑ See also Ruth Andreas-Friedrich: Der Schattenmann / Schauplatz Berlin. Diary entries 1938–1948. Frankfurt am Main (Suhrkamp) 2000; and: Gernot Jochheim : The non-violent action , Hamburg (Rasch and Röhring) 1984, p. 261f; Wolf Gruner : The factory action and the events in Berlin's Rosenstrasse. In: Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): Yearbook for Antisemitism Research 11 , Metropol Verlag, Berlin, 2002; and: Documentation on the protest .

- ↑ Roland Appel , p. 32ff, in: Roland Appel, Dieter Hummel (ed.): Beware of the census - recorded, networked and counted. 4th edition. Kölner Volksblatt Verlag, Cologne 1987.

- ↑ See e.g. B. the 19th activity report 1998 of the State Commissioner for Data Protection Baden-Württemberg ( Memento from June 13, 2009 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Theodor Ebert: Nonviolent uprising. Alternative to civil war. Frankfurt (Fischer) 1970, p. 37.

- ↑ Cf. Theodor Ebert: Nonviolent uprising. Alternative to civil war. Frankfurt (Fischer) 1970, pp. 38-45.

- ^ Gustav Radbruch: Legal injustice and supra-legal law. In: SJZ 1946, 105 (107).

- ↑ On the definition of psychological violence in sitting blockades .

- ↑ Jürgen Meyer : Civil disobedience and coercion according to § 240 StGB. P. 8, in: Martin Stöhr (Ed.): Civil disobedience and constitutional democracy , Arnoldshainer Texte, Volume 43, Frankfurt am Main (Haag + Herchen) 1986, pp. 5–26.

- ↑ Horst Schüler-Springorum: Criminal law aspects of civil disobedience. P. 83, in: Glotz, Peter (Ed.): Ziviler Disobedience in the Rule of Law , Frankfurt am Main (Suhrkamp) 1983, pp. 76-98.

- ↑ See Horst Schüler-Springorum: Penal aspects of civil disobedience .

- ↑ Wolfgang Stock: Possible legal consequences of civil disobedience. In: Wolfgang Stock: Ziviler Disobedience in Austria , Vienna (Böhlau) 1986, pp. 101–125.

- ↑ Nicolaus H. Fleisch: Civil disobedience or Is there a right to resistance in the Swiss constitutional state? Grüsch (Rüegger) 1989, p. 386f.