History of england

The history of England is the history of the largest and most populous part of the United Kingdom . The first written records to prove the existence of what was then Britain are reports from Caesar of his landing in 55 BC. The term " England " comes from the time after the immigration of the Anglo-Saxons . After Wales was first incorporated into the legal area of England, but especially after the ascension of the English throne by James VI. from Scotland in 1603, it became increasingly difficult to distinguish between English and British history. Through the union with the Kingdom of Scotland in 1707, the Kingdom of England became part of the Kingdom of Great Britain. The English Parliament in London took on the role of Parliament from Great Britain.

Pre-Roman England

The history of England basically begins with the creation of the island. In the Mesolithic period, around 8500 BC. BC, the sea level rose during the last ice melt and made Britain approx. 7000 BC. To the island. In the Neolithic Age , which only appeared on the island around 4000 BC. Began, agriculture and animal husbandry began. Whether this is due to immigration from the continent or the acculturation of local hunters and gatherers is a matter of dispute in research. From around 3200 BC. Numerous henges ( Woodhenge , Durrington Walls , Marden Henge , Avebury ) and stone circles ( Castlerigg , but above all the well-known Stonehenge ) were erected as megalithic structures on the British Isles . The Iron Age began from 800 BC. In the south there are many remains of hill forts from this period that have survived as a system of concentric mounds and ramparts: from the great Maiden Castle in Dorset down to the much smaller ones like Grimsbury Castle in Berkshire .

Roman time

The Romans first landed under Caesar's leadership in 55 and 54 BC. In England, but initially not as a conqueror. Not until almost a century later, in AD 43, was England occupied by the Romans under Emperor Claudius and subjugated as a province of Britannia ; the most significant uprising of the Celtic population finally occurred in 61 under the leadership of Boudicca ( Boudicca uprising ). To protect oneself from the looting of the Picts , the inhabitants of Scotland at the time, a protective wall from east to west, Hadrian's Wall , was built under Emperor Hadrian at the height of the Solway Firth .

In the classical Roman style, the Romans built a highly efficient infrastructure to consolidate their military conquests, and thus opened up Britain, although the degree of Romanization was very different: the Roman influence was strongest in the south and east, where urbanization was also stronger was pronounced. From the 2nd century on, Christian proselytizing made its first progress in these regions .

From the 4th century, Britain was ravaged by usurpations several times . Flavius Theodosius reestablished order on the island in the 360s. But only a few decades later, most of the troops were withdrawn; they were needed more urgently on the mainland, where the Rhine frontier had collapsed after the advance of Germanic tribes . In 407/8 most of the Roman troops withdrew and in 409 the island rose against the Roman government. Some time later (the sources are very poor) the Roman presence on the island also died out; the Civitates now had to protect themselves as well as possible, for which Germanic mercenaries were used.

Saxon conquest

In the emerging power vacuum, Pictish groups repeatedly pushed their way south. Since the Romano-British population could not expect any help from the Roman Empire, they recruited Saxon troops to defend them. These mercenaries settled with their families. In the following period, however, groups of Angles , Jutes and Saxons poured into the country as a result of the migration to avoid the population pressure on the mainland. The early Middle Ages began in Britain .

The newcomers settled in East Anglia , the Midlands , East Yorkshire and Lincolnshire , partially driving out the native population. South of the Thames, the cities organized a resolute defense under the leadership of local magnates and, based on the Roman model, mostly employed Saxon federates . The Historia Brittonum reports that from 430 Jutian groups came into the country and settled in Kent . A revolt broke out under these federates in 442/443; After protracted fighting, the British population was pushed westward and had to give up Sussex (southern Saxony), Middlesex (central Saxony) and Essex (eastern Saxony) - the later Saxon settlement areas. At the end of the 7th century, the Anglo-Saxons had subdued the island from Cornwall to the Firth of Forth . Exceptions were the westernmost areas of Dumnonia and Wales and the northern area of Cumbria , and Scotland was able to maintain its independence.

Minor kingdoms

The new settlement areas were initially organized according to the tribal and group structure of the continental areas. At the end of the 6th century, the royal rule and seven competing Anglo-Saxon minor kingdoms developed :

- Northumbria , (from the merger of Deira and Bernicia ), East Anglia and Mercien as the foundations of the angling

- Sussex , Wessex and Essex as foundations of the Saxons

- Kent as the founding of the Jutes is considered to be the first consolidated empire, as the immigrants took advantage of the still intact Roman administration and urban culture. Christianity was adopted earlier than in other regions. Intensive writing and legislative activity takes place after 650.

The political primacy of the individual kingdoms was documented in the person of an overlord who was only referred to as Bretwalda in the 9th century . However, he did not rule over the whole of England, but rather a special position of power among the other kings. Northumbria dominated in the 7th century, Mercia in the 8th century, and finally Wessex gained political hegemony. From around 750 only these three kingdoms existed, because the others had merged into them.

The settlement by the Anglo-Saxons represented a clear break with Roman rule. The culture of the conquerors differed fundamentally from the urban way of life of the Romans. The Anglo-Saxons lived in rural clustered villages and were organized in clans and in family communities with servants around a house father (lord). The growth of these house communities led to the formation of the Anglo-Saxon nobility system with followers as the immediate power centers of a nobleman. In addition, an army kingship was formed based on the election of the leader by the most powerful members of the army. This counteracted the efforts of the army kings to make this office hereditary in the respective family.

Christianization

The Anglo-Saxon peoples brought their own Germanic and especially Anglo-Saxon religion with them during their conquest and, with their Christian beliefs , pushed the Romano-British population into the Welsh border areas.

From the monastery on Iona , which the Irish monk Columban von Iona (Irish Columcille ) had founded in 563, the Irish-Scottish missionary mission of the Anglo-Saxons began from the north. There Oswald of Northumbria converted to Christianity and, as King of Northumbria, called the monk Aidan to be bishop and missionary.

In the south, the Benedictine Augustine landed on the island in 597 and, at the request of King Æthelberht of Kent, whose wife was of Christian faith, began proselytizing the Anglo-Saxons.

Differences arose between the two Christian currents, which were based primarily on the different organizational structures. While the Irish-Scottish missionaries relied on monasteries and only knew flat hierarchies, the Roman mission was based on the episcopal hierarchy with its centers of power in the urban bishoprics. In addition, the different ways in which Easter is calculated led to confusion in people's everyday lives. At the Whitby Synod , the Roman rite prevailed and ties with the continental Roman Church tightened.

Christianity was generally first adopted by the ruling families and passed on to their subjects from there. The new faith offered the nobles the opportunity to found their own churches and thus exercise sacred power. With the educated clerics and monks they also had capable helpers in the administration of their territories. Finally, the anointing offered the army kings an opportunity to justify their power in addition to being chosen by their entourage, thereby reducing their dependence on them and getting one step closer to the hereditary nature of rule.

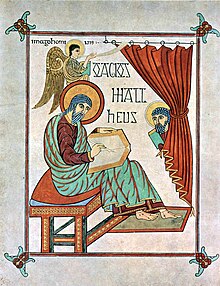

The Christian age produced masterpieces of island illumination such as the Book of Durrow , the Book of Lindisfarne and the Book of Kells . It was shaped by such important teachers as Beda Venerabilis . Around the beginning of the 9th century, the Christianization of England was complete, although strong pagan elements continued to have an effect in popular belief.

Viking age

First attacks and development of the Danish settlement area

Beginning in 789 and historically significant for the first time with the raid of 793 against Lindisfarne Monastery , the Danish Vikings landed in England, marking the beginning of the Viking Age . At first they only carried out lightning-like raids, after which they retreated to the sea. They were safe there, as the English kings hardly had any ships that could operate farther from the coast. Shortly thereafter, however, individual groups of Vikings overwintered on the island and established at least periodic settlements. In 865 Vikings landed in East Anglia with the apparent intention of settling down there longer. They demanded tribute payments from surrounding Anglo-Saxon settlements and built their own villages. A year later, the Great Army conquered York and installed an Anglo-Saxon vassal as king in the Kingdom of Jórvík . The raids on Mercien immediately began, and in 869 the first Danish troops reached the Thames, the river border with Wessex, the dominant Anglo-Saxon empire.

Creation of the Kingdom of England

Alfred the Great , King of Wessex, faced the Danish threat. The constant fight against the Vikings, in which Alfred initially failed to achieve any resounding success in the Battle of Englefield and the Battle of Reading , acted as a catalyst for the extensive unification of England under the King of Wessex. He also forced him to reorganize the army, build a powerful fleet, build numerous castles and create the system based on counties ( Shires ), which gave England a more or less uniform administration for the first time since Roman times. In 878 Alfred defeated a large Danish army at Edington . Thereupon the Danish king Guthrum , who had already come into contact with Christianity, was baptized with 30 of his men. They then withdrew to their core area in East Anglia ( Danelag ). This success led to the recognition of Alfred as ruler in Mercien. In 886 he finally conquered London and gave the empire a center. In the following years, the other Anglo-Saxon territories, including those under Danish rule, recognized him as their ruler (cf. Origin of England ).

Alfred's successors expanded the administrative system he had set up, in which sheriffs were crown officials at the head of a shire . The Shires were especially important for the judiciary and the army. In addition, an early form of an English "national consciousness" developed. Alfred's son Eduard inflicted another heavy defeat on the Danes in the Battle of Tettenhall in 910 and was then particularly successful in disputes with the southern Danish empires. In 918 the kings of these empires recognized him as lord, later also the rulers of Scotland.

Meanwhile, the Danish areas in the east of England, known as Danelag , were also changing . The former Vikings increasingly adopted a peasant way of life, built castles and settlements and adopted Christianity.

King Æthelstan expelled the Cornishmen from Exeter in 936 and secured the River Tamar as the border of Wessex. He called himself Rex totius Britanniae , but could only bring Wales and Scotland under a loose suzerainty. In contrast, he conquered Northumbria permanently. His documents after 930 were made by a single firm in Winchester , which suggests a kind of capital of his kingdom. Up to the late 10th century, Æthelstan was followed by a phase with comparatively few armed conflicts, but with political and ecclesiastical consolidation of the empire, especially under King Edgar .

Around 980 a new wave of Viking attacks from the sea began. Larger battles, however, largely failed to materialize, as the Anglo-Saxon rulers paid tributes and the Vikings withdrew. In order to raise these tributes, King Æthelred, on the advice of Archbishop Sigeric of Canterbury and his " greats ", was the first medieval ruler to introduce a general property tax , the Danegeld . Nevertheless, the Vikings continued their efforts to conquer the Anglo-Saxon territories. After losing the Battle of Maldon in 991, Æthelred paid 10,000 pounds (3,732 kg) of silver to buy the Vikings' departure. These sums increased over time. In 994, 7,250 kg of silver had to be used for Olaf Tryggvason's withdrawal , and in 1012 even 22 tons of silver.

In 1002 Æthelred married the Norman duke's daughter Emma in anticipation of Norman support against the Vikings. In doing so, he laid the foundation for the later Norman conquest of England. In the same year, for fear of an assassination attempt, he ordered all Danes in his domain to be murdered on November 13, 1002 . But the Danes even responded with increased attacks.

In 1013 the Danish King Sven Gabelbart set sail for a raid and conquest in England, whereupon King Æthelred fled to Normandy and left him with power. When Gabelbart died in 1014 just a few months after his coronation, Æthelred allied himself with the future King of Norway, Olaf Haraldsson, and returned to the throne. Knut, the son of Gabelbarts, also claimed the throne and in 1015 sailed with a large fleet from Denmark to England, where he defeated Edmund Ironside, the son of Æthelred, who died during the siege.

England under Canute the Great

Canute the Great was crowned King of England in 1016 and ruled England and Denmark in personal union as well as large parts of Norway and southern Sweden from 1018 . England was thus part of a great empire held together by seafaring. Knut's rule over England represented an extraordinarily long period of peace for the country. England recovered after decades of Viking raids and the Danegeld was abolished. Knut married Emma, Æthelred's widow , and converted to Christianity . The Christianization in Denmark and in 1028 conquered by Knut Norway began with Anglo-Saxon priests. In addition to including the church in his ruling structures, Knut tried to integrate both the Anglo-Saxons and the settled Danes in his newly created North Sea region . The population groups were largely treated the same by the king, but differed in the various legal systems that applied to them, which had developed from Germanic tribal constitutions . The king's most important legal tool was the king's peace , with which settlements, manors, facilities (e.g. churches, streets or bridges) and groups of people (e.g. Jews) were taken over into the personal household of the king and thus protected. As an additional administrative level over the Shires, the king, who was rarely present in England, set up four earldoms ( Wessex , Mercia , East Anglia and Northumbria ), each of which was administered by an Ealdorman . When making political decisions, he usually consulted the greats of the country.

The last Anglo-Saxon kings

After the death of Knut's son Hardiknut , the Anglo-Danish empire broke up, and Norman influence in England grew noticeably. In 1042 Hardiknut's half-brother Eduard the Confessor , a son of Æthelred and Emma, took over the English throne. Through his 25-year stay in Normandy, Eduard was alienated from domestic conditions. Under him there were two developments that quickly provoked conflicts: on the one hand, the influence of both the old Anglo-Saxon and Danish nobility, especially the earls of the duchies, and on the other hand, Eduard preferred Norman nobles at his court. This led to a conflict between the established nobility and the Normans. Edward's father-in-law Godwin, Earl of Wessex headed the opposition movement against the Normans. First, Eduard defeated Godwin and sent him into exile in 1051. A year later, however, Godwin came back and quickly established himself as the most powerful nobleman in the country. Up to this point, Eduard had introduced the new rulership organization that the Norman kings were to enforce later, in particular with the direct royal appointment of clerics to administrative posts and bishoprics based on the model of the Ottonian imperial church system . When Godwin returned to England, Edward began to withdraw increasingly from his government business and to worry only about the building of Westminster Abbey and his personal religious exercises.

Harold Godwinson , a son of Godwin, managed to get the childless Eduard to appoint him as his successor. However, this by no means resolved the question of the succession. Although Harold was the most powerful political figure in England and, according to his own statements, had the promise of Edward that he would be his successor, it was disputed whether this promise was actually made and whether it was legally binding. In addition, Harold was not related to the royal family. A still underage great-grandson of Æthelred, who lived in Hungary, and the Norwegian king Harald III could rely on family legitimation . Hardråde called as grandson of Canute the Great. Wilhelm, Duke of Normandy, was at least distantly related to the Anglo-Saxon royal family through his great-aunt Emma. He also relied on a controversial oath Harold Godwinsons had taken when he was taken prisoner on a trip to Norman and had assured William the succession to the throne in England.

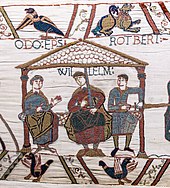

After Edward's death in 1066, Harold Godwinson was first recognized as the new king by the greats of the empire. Harald of Norway and Wilhelm of Normandy began preparations for campaigns in England immediately after the election. Harald was the first to reach the island and landed in Yorkshire with 300 longships. At the Battle of Stamford Bridge on September 25, 1066, Harold repulsed this invading army. On the morning of September 28, the Normans landed in the southwest near Pevensey . Harold had to lead his army, weakened by the battle, in forced marches towards the new attacker. On October 14, 1066, the English troops were defeated in the Battle of Hastings , in which Harold and his brothers were killed. After that Wilhelm hardly met any resistance. On Christmas Day 1066 he was crowned King of England in Westminster.

England in the High Middle Ages

Building the Norman rule

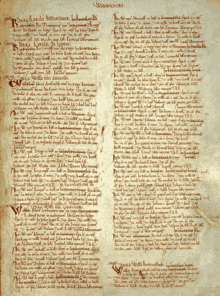

The victory of Wilhelm led to the introduction of the effective feudal system of the Normans . A small Norman upper class almost completely replaced the established nobility. Wilhelm ordered the creation of the Domesday Book , which recorded taxes on the entire population, their lands and possessions. Unlike in many other European countries, with William the English kingship established itself as the sole center of the feudal system. Ultimately, the entire property on the island was in the hands of the king, who passed it on to his tenants, who in turn had subordinate tenants . There was no manorial rule based on the princes' own power, such as in the Holy Roman Empire. The administration of England was also reorganized by William: With a few exceptions, the counties were introduced as new, smaller areas. At their head were Earls or Counts as royal tenants. Underneath, however, there was another layer of sheriffs as officials directly responsible to the king. Church offices were also increasingly occupied by Normans. Overall, the Norman domination resulted in the English ruling class to the fact that Anglo-Norman and Latin became the dominant languages. Anglo-Saxon was only spoken by the common people. In the legal system, the Norman influence was particularly noticeable through the new element of jury courts and through the clear separation of secular and spiritual jurisdiction.

There were disputes over the inheritance among Wilhelm I's sons, from which Henry I finally emerged as the victor and ruler over both England and Normandy. In 1100 Heinrich had to grant the nobility the Charter of Liberties , the forerunner of the Magna Carta , to secure his rule . Under him, the investiture dispute between the English crown and the Catholic Church was fought, which ended with the regulation that the church was allowed to give the bishops spiritual powers, but that they had to become vassals of the king beforehand. Until the end of his reign, Heinrich established further elements of a central royal rule with the Lord High Treasurer , an administrative court and the travel judges. The loss of his son William in 1120 in the sinking of the " White Ship " initiated disputes over the succession that would last about 20 years.

Civil War and Plantagenet Dynasty

The rule of Stephan I (1135-1154), a nephew of Heinrich, was marked by increasing unrest and the decline of the royal rule in favor of the nobility. Heinrich I's daughter, Matilda , had first married the German Emperor Heinrich V and then Gottfried von Anjou . Together with him and her half-brother Robert von Gloucester and an invading army, she returned to the island in the autumn of 1139. Stephan was captured in 1141. Matilda declared herself queen, but quickly met with opposition from the population and was expelled from London. Riots and civil war continued until Matilda returned to Normandy in 1148. Stephan continued to rule until his death in 1154, after in 1153, under the pressure of an impending invasion, he had reached an agreement with Heinrich from the house of Anjou-Plantagenet , the son of Matildas and Gottfried and later Henry II of England, which guaranteed his successor .

With his accession to power and his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry II founded the Angevin Empire , which included England, parts of France and the Iberian Peninsula . At the same time, however, Henry, as the most powerful prince in France, was in direct conflict with the French crown, into which England was drawn.

Under his rule, the kingship strengthened again, which was expressed above all in the expansion of the legal system. All free people were given the right to turn to the king directly in legal disputes, and the nobility's self-help rights were restricted. To enforce these innovations, travel judges (Justice in Eyre) and jury courts were increasingly used. By building castles and setting up a mercenary army, the king made himself largely independent of his knights. In relation to the church, Heinrich only partially prevailed: he enacted the Clarendon Constitutions in 1164. They should also extend royal jurisdiction to clergy, restrict ecclesiastical jurisdiction, and prohibit English priests from appealing to the Pope. This led to opposition from Chancellor Thomas Becket , Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1170 Becket was murdered (probably on the "advice" of Heinrich). The worship of martyrs, which began immediately, was also directed against the king, who then had to publicly humiliate himself and lift the ban on appeals. In 1169, an Irish king called English mercenaries into the country to support internal fighting and made contact with Heinrich. After the English knights had quickly conquered large parts of the neighboring island, Henry II went to Ireland himself in 1171 to prevent the knights from becoming too independent there. Henry received homage at the Synod of Cashel , which made Ireland a lordship subject to the crown from the English perspective. Since 1155 Henry also enjoyed through the papal bull " Laudabiliter " of the English Pope Hadrian IV. The right to enforce the submission of the Irish Church to Roman suzerainty.

Heinrich II, however, had not succeeded in establishing a reliable inheritance regulation for his empire. His eldest son Richard the Lionheart was engaged in campaigns in France and the Third Crusade when Heinrich died in 1189 . When he returned from the Holy Land, he was taken prisoner by Emperor Henry VI. Overall, he only spent a few months in England in ten years of reign. After a large ransom was paid for Richard's release in 1194 and he returned to his empire, he fought successfully against Philip II of France, but failed to recapture all of the territories that had been lost in his absence. This is how the Angevin Empire began to shrink. In the following years Richard concentrated on dealing with the rebellious nobility in Aquitaine. During the siege of Châlus-Chabrol Castle , he was hit by a crossbow bolt . He died on April 6, 1199.

His brother Johann took over the rule . When he lost an even larger part of his land holdings in the Franco-English War from 1202 to 1214 and was unable to assert himself in disputes with the church, the nobility defied a number of concessions that are laid down in the Magna Carta of 1215 . When Johann revoked these concessions, the First Barons' War broke out . Johann died during the war, the Regency Council for his underage son Heinrich III. confirmed the Magna Carta again. This ended the civil war and a French army that had landed in England to support the rebels had to leave England again in 1217. Also as Heinrich III. came of age, he repeatedly confirmed the Magna Carta, which thereby became a basis of English politics.

English parliamentarianism emerged

Under the weak kings after Henry II, the stability of the system he created became apparent. The institutions and the nobility maintained the Kingdom of England in spite of the ruler's absence and frequent opposition to him. England began to develop very early from a union state to a comparatively modern parliamentary monarchy . Under Henry III. The power of the nobility continued to grow: first of all, a regency council carried out government affairs for the underage king. After Heinrich himself came to power, he quickly overstrained his strength through engagements in Sicily , in the empire and through an equally unsuccessful attempt to recapture the French territories. In addition, the growing influence of French court nobles met with the reluctance of the English nobility. When the King convened a meeting of the Grand Council, also known as Parliament , in order to obtain financial support in 1258 , a group of magnates rebelled . They demanded that in future the king should no longer determine the composition and convocation of parliament and the structure of his permanent advisory group himself. In the Provisions of Oxford and the Provisions of Westminster in 1258 and 1259, among other things, it was stipulated that a magnate committee with 15 members should oversee all government affairs in the future and that the king was obliged to convene a parliament three times a year. When Heinrich III. tried to revoke the commission, the Second War of the Barons broke out in 1264 . The nobility opposition under Heinrich's brother-in-law Simon V. de Montfort was able to defeat the king and take over the government. To gain further support, Montfort convened De Montfort's Parliament in early 1265 , to which representatives of the towns and the lower nobility were also invited. However, Montfort lost the support of a large part of the magnates who defeated him decisively in 1265 under the leadership of the heir to the throne Eduard in the Battle of Evesham .

Even before he came to power in 1274, Eduard became the most important bearer of royal rule in England. He strengthened the kingship but left both the Magna Carta and Westminster Commissions in effect. In cooperation with parliament and magnates, he also implemented a comprehensive legal reform, which above all meant a departure from Germanic customary law towards codified and binding laws.

Expansion into the neighboring territories

In two campaigns from 1277 to 1283 Edward I was able to defeat the Welsh princes and conquer the country. He then initiated a targeted Anglicization of the country by founding settlements and building castles. The conquered areas were divided into counties following the English model and subjected to the English legal system. Welsh uprisings could be crushed quickly by the beginning of the 14th century. In Scotland, Eduard was initially active as an arbitrator in a controversy for the succession to the throne and tried to force the local nobility into a vassal relationship to the English crown through his candidate. In 1296 he intervened militarily in the northern neighboring kingdom, deposed King John Balliol and claimed the Scottish crown himself. There was Scottish resistance and by 1314 several reciprocal campaigns followed , in which neither side prevailed. In 1314 the Scots achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Bannockburn , after which Scotland remained independent until 1603. In 1169, Anglo-Norman nobles began to conquer Ireland . By the middle of the 13th century, a thin class of English nobility had spread over large parts of the island as rulers. The grand institutions of England and the more advanced economic system had largely been taken over. As early as 1172, however, Henry II had enforced his sovereignty over Ireland, which as lordship Ireland was under the English kings. However, an opposing process began as early as the High Middle Ages : the English ruling class slowly adopted the Gaelic culture and mixed with the remaining local nobility. In some cases, lower nobles of English origin and English settlements even paid tribute to Gaelic lords. Gaelic civil and criminal law increasingly prevailed again in the structures of English constitutional law. Until the late Middle Ages one can only speak of actual English rule in the region immediately around Dublin.

Economy and Society in the High Middle Ages

In the period from the middle of the 10th to the middle of the 14th century, the English population is estimated to have tripled, probably up to six million people. This development had a number of economic and social consequences: arable farming was intensified with the introduction of three- field farming and the reclamation of more areas. However, self-sufficiency with food was only possible in climatically favorable and politically stable times. Grain was often imported, as well as large quantities of wine and wood. The main export items were wool, iron and tin. Long-distance trade was mostly in the hands of continental European and Jewish merchants. There were hardly any English merchant ships.

The Norman conquest brought about a change in the village structures, with rural settlements increasingly grouping around the mansions of the nobility and no longer in cooperative villages according to Anglo-Saxon tradition. The growth of cities was mainly due to Viking impulses . However, large settlements quickly formed outside of the Danelag , which were soon given the status of boroughs with self-administration and separate jurisdiction by the king . With the exception of London, which had around 50,000 inhabitants in the High Middle Ages, the English mostly remained much smaller than continental cities. The high nobility is estimated to be around 170 families in the High Middle Ages. Around 5000 to 6000 knights were subordinate to them, who in turn had the unfree peasants as serfs. Free peasants were direct subjects of the king and enjoyed legal privileges vis-à-vis the unfree. Since the knights increasingly replaced their vassal services with monetary payments in the course of the Middle Ages, they had more and more time to manage part of their goods themselves, which was not done by unfree peasants, but by farm workers on the manors. The social structure experienced a change when all Jews were expelled from England in 1290 .

Spiritual Life in the High Middle Ages

After the Norman conquest, science and art in England were oriented towards developments in France, with their centers in Paris and the cathedral schools in northern France. In England, too, schools were initially founded in the episcopal cities in order to supply the church with a new generation of educated clergy. Universities began to emerge shortly before 1200 in Oxford and from 1209 in Cambridge , initially as loose associations of scholars and students, shortly afterwards specifically promoted and controlled by the king and the church, and from the middle of the 13th century also with permanent university buildings. Around 1220 the universities were also the first centers of activity in England for the new mendicant orders, the Dominicans and Franciscans .

Linguistically, the Norman conquest had led to a dichotomy: While the upper class Anglo-Norman language, English remained the language of the majority. After the French parts of the Angevin Empire had been lost, various Middle English dialects first prevailed among the landed gentry . Later the dialect dominated the London region and became the origin of modern English.

England in the late Middle Ages

Hundred Years War

The rise of the French kingship led to Philip VI. 1337 the Gascony confiscated because the English King Edward III. had violated his vassal duty to him. Eduard did not want to accept the final loss of the French possessions. In addition, Gascony was of great importance for the English wine trade. The fact that the fled Scottish King David II was staying at the French court also played a role . In return for the confiscation, Eduard III. Claim to the French throne, which started the Hundred Years War. After a victory in the naval battle of Sluis (1340), Eduard landed on the French mainland with four armies operating on a broad front. After the victory in the Battle of Crécy-en-Ponthieu (1346) and the conquest of Calais by the English, the French king had to enter into an armistice. The new beginning of the fighting in 1355 and another English victory under the leadership of the " Black Prince " in 1356 in the Battle of Maupertuis caused a deep crisis in France. In the Peace of Brétigny , Edward III secured himself. 1360 large territorial gains in France.

This was followed by a period of military failure for the British. In addition, the entire warfare burdened the state treasury more and more and the catastrophic consequences of the first plague wave of 1348 shook the English economy badly. The difficult military situation with simultaneous economic crisis and lack of fighters plunged the crown into considerable financial difficulties. The lack of money could only be remedied with new taxes, which the parliaments also granted the king. In return, they received the right to approve all future tax collections. This gave the parliaments their hand over centuries of power over the king. In addition, they enforced the abolition of the travel judges and thus a supervisory authority, who were replaced by the stationary justice of the peace. In 1376, the “ Good Parliament ” implemented a restructuring of the royal advisory group for the first time in collaboration with the Commons and Lords. In 1383 a campaign by Richard II to Flanders failed . This was followed by a phase of continued armistices until 1415, during which the Hundred Years War largely rested.

Richard II had to contend with revolts in the late phase of his rule. When he was on a campaign against the rebellious Henry IV in Ireland, an armed opposition formed in northern England under the leadership of the Archbishop of Canterbury. After his return, Richard was imprisoned by Heinrich in England in 1399, imprisoned in the Tower of London and forced to abdicate . Parliament sanctioned this procedure and awarded Heinrich the crown. With that it had attained an unprecedented level of power.

In 1415 the son of Henry IV, Henry V , took advantage of the unrest in the succession to the throne in France to become active again militarily on the continent. In the Battle of Azincourt he achieved a resounding victory, conquered all of Normandy by 1419 and formed an alliance with Burgundy . After the death of Henry V in 1422, the war did not flare up again until 1428. Jeanne d'Arc developed into a charismatic leader on the French side, and the Anglo-Burgundian alliance broke up. A series of French successes followed, which were crowned in 1453 in the Battle of Castillon with the conquest of Bordeaux. This ended the Hundred Years War, and England lost all of its mainland possessions except Calais .

In church politics, during the war with France, the English church was increasingly distancing itself from the papacy, weakened by the schism . In several statutes from the second half of the 14th century, the crown gained control over the benefice system and restricted the possibilities of appellation to Rome. Eventually the clergy became taxable to the king. Still, the papal influence did not entirely disappear. A spiritual challenge arose with the pre-Reformation Lollard movement of John Wycliff , which propagated a mystical Christianity with a universal priesthood. From 1380 Wycliff gained supporters in parliament and aristocratic circles. In addition, peasant revolts developed in the vicinity of the lollards in 1381, 1414 and 1431.

Wars of the Roses

The deposition of Richard II by the later Henry IV and the failures in the Hundred Years' War were the reasons for the outbreak of the Wars of the Roses . They were a power struggle for the English crown between the House of Lancaster , whose coat of arms contained a red rose, and the House of York , which had a white rose in its coat of arms. Social and economic reasons were the existence of large armies after the Hundred Years' War, which had no fields of activity outside of England, and the consequences of the plague.

The usurpation of Henry IV had left considerable uncertainty about the succession to the English throne. The reign of Henry VI. then weakened the kingship further because of his minority and later because of mental illnesses. In this situation York and Lancaster, both related to the Plantagenets, claimed rule. After eventful battles, Eduard von York was crowned Edward IV in 1461 . By 1471 he had also prevailed militarily, whereupon he Heinrich VI. murdered. A successful campaign to France in 1475 secured Edward's rule financially. The Wars of the Roses flared up again in 1483 when Edward's brother Richard III. his nephews, the heir to the throne, imprisoned and probably murdered and declared himself king. This led to uprisings in England, which the last Lancaster heir, Heinrich Tudor, who fled to France, took advantage of. At the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, Richard III. slay. Heinrich Tudor became the new king as Henry VII. In 1486 he married Elizabeth of York, the daughter of the dead Edward IV, and thus united the two warring houses. With this he initiated a phase of stability for the English crown.

Welsh last survey

Previously there had been a rebellion in Wales from 1400 , in which the Welshman Owain Glyndŵr declared himself Prince of Wales and brought large parts of the country under his control. It was only after several campaigns that Prince Henry (later Henry V ) succeeded in retaking Wales by 1409 and finally put down the rebellion by 1412. This attempt to shake off English rule was the last major uprising of the Welsh. In 1497 Michael An Gof led Cornish rebels in a march on London. In a battle on the River Ravensbourne at the Battle of Deptford Bridge , An Gof and his men fought for the independence of Cornwall on June 17, 1497 , but were defeated. This fight was the last major rebellion before the Civil War .

Economy and Society in the Late Middle Ages

After the growth phase of the Early and High Middle Ages, the plague shaped development in England in the late Middle Ages . After two severe plague attacks in 1348 and 1361/62 there were several small outbreaks of the epidemic, which roughly halved the population. This development resulted in a widespread labor shortage from which, after an initial severe economic crisis, the surviving rural population in particular benefited: Agricultural workers received higher wages, free farmers bought the land that had become free and in some cases rose to become large farmers ( Yeomen ). The competition from self-cultivated goods of the nobles declined, as they withdrew from agriculture in view of rising wages and turned away from agriculture and turned to sheep breeding. Although some smaller free peasants also became dependent, the majority of the unfree received further rights from their masters, which were increasingly set down in writing and thus legally enforceable. As a result, serfdom had largely disappeared by the end of the Middle Ages . Overall, the class consciousness of the rural population grew, which was most clearly expressed in the peasant revolt of 1381 around Wat Tyler . The first, successful phase of the Hundred Years' War in particular had profound effects on the nobility. The classic vassal relationship turned into contractual relationships in which the crown or noblemen bought the military services of the landed nobility with lifelong maintenance payments. On the one hand, this increased the ability of the crown to carry out long campaigns, but on the other hand, it made powerful private armies available to the magnates.

After the great plagues were over, the development of cities accelerated, especially London. For the first time a larger layer of local long-distance traders emerged. Above all, London benefited from its function as a royal seat, which was established from the 13th century. Merchants' and craftsmen's guilds were given privileges to supply the farm. The king's need for money laid the foundation for London's banking system. The conquests in the early phase of the Hundred Years War increased the amount of money in circulation in England, so that the money economy finally prevailed in the second half of the 14th century.

Parallel to the expansion of sheep breeding and long-distance trade, the raw wool was increasingly processed into cloth in the country, which resulted in greater added value and well-paid jobs for the rural residents.

Tudor era

Consolidation of the Tudor rule

At the latest with the birth of his son Arthur on September 19, 1486, Henry VII's position as king was largely stable. In the following years he tried above all to combat the potential for insurrection among the remaining supporters of the House of York and to stabilize the royal finances. To this end, he created a number of offices whose owners had to cede fees. He rarely used special taxes that a parliament would have had to approve in order to keep his dependence on the assembly small. In the final stages of his reign, Henry pushed back the influence of the great noble houses by establishing the Council of the North and the Council of Wales . These two assemblies, each chaired by a bishop, involved not only the magnates, but also the lower landed gentry in political decisions about the respective region. In addition, Henry VII set up further advisory committees in which the magnates no longer dominated, but in some cases members of the bourgeoisie also became influential.

First years of reign of Henry VIII.

His son, King Henry VIII , tried again to retake the mainland areas. However, the campaigns in France did not bring lasting success. Only in 1513 succeeded in conquering Thérouanne and Tournai with a disproportionate military effort . James IV of Scotland used this campaign to invade northern England. His outnumbered army was defeated by the English defenders in the battle of Flodden Field , in which the king was also killed. His son Jacob V was underage and so his mother Margaret Tudor , a sister of Henry VIII, took over the reign, which secured the English king great influence in Scotland. Apart from his campaigns, Henry VIII cared little about politics. He left this field largely to his advisor Thomas Wolsey . The man of simple bourgeois origin became one of the most powerful men in England, but fell in 1529 over his failed attempts to arbitrate in the disputes between the Habsburg Empire and France and to obtain a divorce from the royal marriage.

During the first years of Henry VIII's rule, the question of succession to the throne and thus of the king's marriage became the focus of politics. With Katharina von Aragón , who had previously been married to Heinrich's deceased brother, he only had Maria, born in 1516, as a child. Several miscarriages followed. A lack of heir to the throne would have had catastrophic consequences for the continued existence of the Tudor dynasty. In this situation, Heinrich met Anne Boleyn , who, however, did not want to be modest with the position of mistress, but demanded that she become queen. Negotiations with the Pope began to divorce Heinrich from Catherine. However, they were largely unsuccessful, especially at the instigation of Emperor Charles V , a nephew of Katharina's. Over this failure Wolsey finally fell. His successor as Chancellor was Thomas More , who refused to continue the divorce negotiations.

Break with Rome

At the same time, the population became increasingly dissatisfied with the Catholic Church. Above all, the income of the clergy from benefices and the often inadequate pastoral care in the parishes triggered growing outrage. In the autumn of 1529, mainly London merchants and jurists formulated criticism of the church in a hitherto unknown degree of severity. In 1530 the king brought charges against the entire English clergy for alleged violations of canon law. In January 1531, Henry VIII forced the English bishops' assembly to accept the king's sovereignty over canon law. In addition, the king demanded the abolition of the right of appeal to the Pope, which not only gave him a free hand in his divorce, but would have largely withdrawn the English Church from Rome's grasp. In addition, the Archbishop of Canterbury was to be recognized as the highest cleric in England, a position he previously shared with the Archbishop of York. The theoretical foundation for these claims was what is known as Caesaropapism in research , which also granted the secular ruler sovereignty over the church in his territory. Henry VIII wanted to achieve this position of power. He received support from the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer . In January 1533, Anne Boleyn announced that she was pregnant by Henry VIII. Cranmer immediately trusted them. In May, a court dominated by him declared the marriage between Heinrich and Katharina invalid, which meant that the daughter Maria was illegitimate and therefore not entitled to inheritance. The Pope annulled the sentence and excommunicated Cranmer and the king. In this situation, Elisabeth , the daughter of Heinrich and Anne Boleyn, was born on September 7, 1533 .

With the Supreme Act of 1534, the King and Parliament finally established the independence of the English Church from Rome and the position of the King as its head. In addition, numerous, especially legal, special rights of the clergy were abolished. This was the hour of birth of the Anglican Church . In the following years, mainly at the instigation of Vicar General Thomas Cromwell , numerous ordinances were issued that also intervened in liturgy and church doctrine. The king's actions aroused considerable resistance. So the monastic orders rejected the dissolution of Rome and the divorce of the king. Henry VIII had all branches of the order dissolved by 1540 . The lands of the orders and a large part of the land owned by the universal church went free to the crown in the following years and subsequently to deserving followers from the petty nobility ( gentry ) and to wealthy large farmers ( yeomanry ) at low prices . In doing so, Henry VIII created for the future an unconditional leadership elite that would support him with the church and that had a strong interest in preserving the financial advantages and the associated social advancement. The power base of the English crown thus experienced significant economic and political reinforcement and consolidation. Numerous high-ranking clergy refused to recognize the Supreme Act by oath, including Chancellor Thomas More, who was executed for it in 1535. In 1536, the Pilgrimage of Grace , an armed pilgrimage with an estimated 35,000 members, was formed in northern England under the leadership of the lawyer Robert Aske . Heinrich agreed that he would negotiate the demands of the pilgrims, which went far beyond the protest against the royal church policy. On these promises the procession broke up, whereupon the king let the leaders go to trial.

The most pressing problem of Henry VIII was not solved with the gain in power in church politics: the lack of a male heir. In May 1536 he had Anne Boleyn executed, officially for multiple adultery. A few days later the king married the lady-in-waiting Jane Seymour . She gave birth to the heir to the throne Eduard on October 12, 1537 and died in childbed. Pan-European religious policy played a central role in the search for a new wife for the king. Thomas Cromwell campaigned for an alliance with the Protestant forces in the empire and brokered a marriage between Heinrich and Anna von Kleve . When the bride arrived in England, the king was appalled at her unappealing appearance, but entered into the marriage for reasons of alliance. However, Cromwell fell out of favor and was executed on July 28, 1540 for treason and heresy. A court party had previously campaigned against Cromwell for an alliance with France. She now initiated appropriate negotiations and introduced Heinrich to the attractive Catherine Howard . The marriage with Anna von Kleve was immediately divorced, and Heinrich married Catherine on the day of Cromwell's execution.

At the same time, Henry VIII took military action against Scotland, which was allied with France. At the Battle of Solway Moss in 1542 an English army defeated the Scottish troops. Probably out of horror at this news, the Scottish King James V died. In 1543, Henry of Calais started a campaign against France, which with a large military contingent only resulted in the conquest of Boulognes and thus a strategic defeat. Henry VIII died on January 28, 1547.

Incorporation of Wales

Henry VIII incorporated the Principality of Wales as King of England from 1534–1542 , which finally lost its independence. With English law and the English language as the official language from now on, the Welsh- speaking locals were kept away from public office, among other things.

Tudor crisis

The affairs of government for the still underage Edward VI. took over the 16-member Privy Council , in which the protector Edward Seymour , the brother of Edward's mother, quickly assumed a dominant position. Seymour had to deal with several problems: In the war against France and Scotland, public opinion demanded success from him, at the same time the campaigns weighed heavily on the treasury. In addition, the church political course was controversial among the members of the council and the magnates. While some called for a connection to the Reformation, there were also numerous voices in favor of largely retaining old beliefs despite the Rome solution. Edward Seymour repealed numerous censorship and heresy laws in the face of this question, so that a broad debate unfolded and relieved him of the need for central regulations. With several detailed laws, especially on the liturgy, the Lord Protector favored Protestantism. The most important was the Uniformity Act of 1549, which laid down the first Book of Common Prayer as a binding order of worship.

At the same time, the social situation came to a head. The reasons for this were the high taxes to finance the war, population growth, poor harvests and inflation. These tensions erupted in Devon and Cornwall in 1549 in the Western Rebellion . The reason for the surveys, however, was church legislation. Clerics who campaigned against the curtailment of church power and for the retention of old forms of worship became leaders of the rebellion. In 1552 a second Book of Common Prayers followed , with which the Anglican Church finally joined Protestantism.

From 1551 Edward Seymour increasingly lost his power to John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland , chairman of the Privy Council. This tried to end the war and to fight mass poverty. In this situation the not very robust Edward VI fell ill. 1553 of tuberculosis. Since his death was foreseeable, an alternative line of succession moved into the center of the political dispute. Officially Maria I was still entitled to inheritance. As an avowed Catholic, her government would have meant considerable upheaval and probably also the removal and punishment of the Protestant Dudley. He then tried, contrary to the regulation of succession to the throne , to build Jane Gray , a great niece of Henry VIII, as the new queen. When Edward VI. died in July 1553, Dudley claimed the title of king for Gray, while Mary proclaimed herself queen. Dudley's attempt to capture Maria failed because his troops deserted because they, like the majority of the population, viewed Maria as a legitimate queen regardless of their denomination. Soon the Council also supported Maria. Dudley was executed.

Reign of Mary I.

At the beginning of her reign, Maria opted for an integrative policy. It left a large part of the old Privy Council in its position of power and added personal, mostly Catholic confidants to the body. First of all, their policy of re-Catholicisation made itself felt mainly through the removal of a few, downright Protestant bishops and the installation of determined Catholics. In 1553 the old, Catholic liturgy was largely restored and religious censorship tightened again. However, it was only Maria's marriage policy that led to an intensification of denominational conflicts. Through her marriage to Philip II of Spain in 1554, she established a connection with the leading Catholic power, which was rejected by the magnates and large parts of the English population. Although she made numerous concessions that were intended to prevent Spanish influence on English politics, discontent with her rule grew. Also in 1554 the Anglican Church was again subordinated to Rome. For the time being, the magnates and the aristocracy agreed because they were allowed to keep their acquisitions from church property. The heretic laws, which were restored in the same year, however, formed the basis for the persecution of Protestants from the following year, during which almost 300 people were burned at the stake. A resounding success of the recatholicization did not materialize, however, mainly because Maria died in 1558 without having given birth to an heir to the throne. Only in terms of foreign policy was there a rapprochement with Spain, when England joined it in the war against France in 1557, an undertaking which, however, turned into a disaster when, on January 7, 1558, England's last bridgehead on the continent, the port city of Calais from France was conquered. Apart from that, however, Maria managed to put the crown on a stable financial footing through a series of reforms and to initiate a naval building program that would play an important role for England in the centuries to come .

Spiritual Life in the Late Middle Ages and in the Early Modern Age

The language of the surrounding area of London increasingly prevailed as the entire standard English language, taking numerous loanwords from French. After literature in the High Middle Ages had almost exclusively an ecclesiastical connection, more and more lay people appeared as authors towards the end of the Middle Ages. The emerging English national consciousness was increasingly reflected in the literature written in the national language. The ability to read and write increasingly spread among urban artisans and traders. In 1525 the first English edition of the New Testament appeared, translated directly from the Vulgate . However, starting with the Renaissance in the 15th century, a return to antiquity under the sign of humanism became noticeable. A wave of church-independent school foundations can also be observed in this century. In the curricula of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, the religious subjects were freed from their dominant positions as part of the Reformation under Henry VIII. From 1500 the number of students increased significantly. Noble sons increasingly used the universities, as the aristocracy as a whole placed greater emphasis on education. Also as a result of the Reformation, English replaced Latin as the measurement language. As a result of the religious upheavals and the associated church looting in the 16th century, the visual arts and architecture experienced a phase in which hardly any new works were created.

Elizabethan Age

According to Henry VIII's succession to the throne and the assurances made by Maria I to the magnate when she married, Elizabeth I ascended the throne in 1558. The new, Protestant queen was enthusiastically received by the people. From the beginning of her reign, a possible marriage of the queen was the dominant theme. Several parliaments have asked them to do so with the aim of obtaining a male heir to the throne.

Implementation of the Reformation

Initially, however, Elisabeth became politically active for Protestantism. In the year of her accession to the throne, she revoked Roman sovereignty over the English Church. In 1559 she made all officials, including all clergymen, swear an oath to be head of the church. 17 bishops appointed by Mary refused this oath and were removed from their offices. In the same year, the religious conformity of the common population was codified with an obligation to attend church services. Theologically, the Anglican Church was finally geared towards Protestantism in 1563 with the 39 Articles drawn up by the clergy , which became law in 1571. Determined Protestants, for whom this did not go far enough, gathered in the movement of the Puritans , some of whom became radicalized from 1570 onwards under the name Presbyterians . Elisabeth took sharp action against these currents, so that from 1590 there was practically no resistance to royal church policy in the Anglican Church. Rome reacted to the turn to Protestantism in 1570 with the excommunication of Elisabeth and a targeted counter-reformation . From 1574, Catholic clergymen, soon also Jesuits , infiltrated England. A total of 650 Catholic priests are said to have worked in England during Elizabeth's reign. They were mostly covertly active in the households of the nobility and gentry; Catholicism no longer found supporters among the common people. Elisabeth reacted with harsh anti-Catholic laws. From 1585 the death penalty was imposed on discovered Catholic priests. In total, Elisabeth had 133 priests and 63 Catholic lay people executed.

Growing influence on Scotland

Elizabeth's first foreign policy activities focused on Scotland. There Marie de Guise , the widow of Jacob V, incurred the massive discontent of the nobility because she ruled with the help of numerous French advisors and soldiers. Elisabeth supported a revolt of Protestant Scottish nobles that broke out in 1559. After Marie's death in 1560, the Treaty of Edinburgh was signed, which should increase the English influence on Scotland and decrease the French. Shortly afterwards, however, Mary Stuart , the widow of Francis II of France , came to Scotland and asserted her claims to the throne. Since she was the legitimate heir to the throne under inheritance law, the Protestant nobles also initially accepted the Catholic queen. However, after Maria had her Scottish husband killed in 1567, a general uprising broke out against her, which forced her to renounce the crown in favor of her one-year-old son Jacob and recognize a Protestant regent. In May 1568, Maria Stuart fled to England and placed herself under the protection of Elizabeth. This found herself in a political quandary: Mary was clearly the legitimate Queen of Scotland who had been driven out by an uprising. If Elisabeth had supported this claim, a Catholic ruler would have come to the throne again in the neighboring country. Although the parliaments repeatedly pushed for the execution of Maria Stuart, this did not take place until February 8, 1587.

Conflict with Spain

Meanwhile, relations between England and Spain had deteriorated. While Spain supported Catholicism in England, English privateers, with Elizabeth's approval, attacked Spanish ships in the English Channel and England supported the Protestant Netherlands in their revolt against Spanish rule. Spain responded with attacks on the Anglo-Dutch trade lines. In 1569 a Spanish-backed uprising broke out in the north of England, which Elisabeth could only suppress with massive use of force and thanks to the support of the Protestant forces of Scotland. Elisabeth then intensified her support for the now organized insurgents in the Netherlands around William of Orange . In 1574 the situation eased temporarily when Philip II and Elizabeth I signed an agreement that forbade each other from supporting rebels and restarted trade between the two empires. Nonetheless, internal resentments against the other state grew in England and Spain. Finally, in 1585, Philip decided on a large-scale invasion of England, in which he received massive financial support from the Vatican.

In 1588, the technically superior English fleet defeated the Armada in a series of naval battles in the Channel. Storms finally destroyed the fleeing Spanish fleet. With this began England's rise to sea and colonial power. Although the first English expeditions to North America had already taken place around 1500, there was initially no targeted policy of conquest. Larger overseas trade did not take place until 1550 and was based primarily on the initiatives of individual English traders. In the course of the dispute with the Spaniards, the crown increasingly supported trade and piracy in Spain's sphere of influence. The seafaring nation of England reached its first high point with Francis Drake's circumnavigation of the world from 1577 to 1580. Several campaigns promoted colonization and overseas trade among the English public. The Anglo-Spanish War did not end until 1604.

From 1600 there was an uprising against English rule in Ireland, which still had a large Catholic population, supported by troops from Spain . However, until 1607 the English troops crushed the movement. After this decision, the English colonization, which had previously only progressed in small steps, began to encompass the entire island.

Last years of Elizabeth's reign

From 1590 the support for Elizabeth I began to wane. The main reason for this was the growing tax burden. Until the victory against the Spaniards, it had little financial burden on the population. In the 45 years of her rule, she only had to convene 13 parliaments, the main task of which was to approve new taxes. However, as continued fighting with Spain followed the destruction of the Armada, the state's need for money grew rapidly. In addition, Elisabeth had created a system of offices at court, in the justice system and the church as well as economic privileges with which she rewarded important magnates. In the years before her death in 1603, this system devoured ever larger sums of money and placed an additional burden on the household.

Economy and Society in the 16th Century

By 1550, the English population had grown again to around three million after the plague. The rural population was by far the majority. However, by 1500 London already had a population of 60,000 and grew to around 215,000 by the end of the century. The next largest cities around 1500 were significantly smaller: Norwich with 12,000 and Bristol with 10,000 inhabitants. An influential class of long-distance traders also formed in London, mainly serving the London-Antwerp route and giving itself an institutional framework for the first time around 1500 with the Guild of Merchant Adventurers . Last but not least, this guild, granted many privileges by the kings, led to the rise of London and at the same time to the stunted long-distance trade in the other port cities of England.

The strong population growth and the final assertion of the monetary economy in all areas of life led to a considerably growing demand for coins, which in turn led to a significant deterioration in the coin metal and inflation . This development led to the impoverishment of large sections of the workforce, who were dependent on wages paid in money. In contrast, both aristocratic and peasant landowners, grocers and, in some cases, tenants with long-term leases made profits. Overall, the importance of food production for sales and no longer just for one's own maintenance rose sharply, especially for supplying the rapidly growing metropolis of London. This also brought about technical innovations, such as the addition of three-field farming with soil-improving forage plants, targeted fertilization and the temporary grazing of arable land, which largely displaced the previous fallow land. Another source of income for the rural population in winter was the publishing system , especially in textile production.

The English peasantry of the early modern period divided into three groups. The worst off were the leaseholders (around 1500 around a ninth of the farmers). They had lease agreements with a limited duration that were repeatedly renegotiated. They have been hit hardest by inflation as a result. The copyholders made up more than half of the peasantry. Their long-term leases were practically non-cancellable and provided for fixed payments for a very long time. The freeholders (around a fifth) were nominally liable to pay taxes to the landlord, but in principle appeared as free farmers.

Throughout the 16th century there were repeated disputes about the privatization of the commons around the farming villages. While the landowners tried to convert this land into private ownership ( enclosure ) in order to increase high-yielding food production, in the face of inflation the landless workers were increasingly dependent on the use of communal property in order to be able to support themselves. The government also recognized these connections and tried to prevent the privatization of the commons with laws, but only partially asserted itself against the interests of the landowners.

In the sixteenth century in England, much earlier than in the rest of Europe, the social barriers between the lower nobility ( gentry ) and the bourgeoisie began to disappear. Influential, wealthy and educated bourgeoisie were able to attain a level with the nobility in terms of reputation. Conversely, it was not dishonorable for younger sons from noble families who were not entitled to inherit, by the end of the 16th century at the latest, to pursue a career as a trader, although by far the majority opted for a clerical or military career.

Spiritual life in the 16th century

Closely connected to the Reformation and a condition for the economic upswing in this epoch was a change in attitudes towards gainful employment and wealth. In hardly any other country has the Protestant work ethic asserted itself as consistently as in England. Gainful employment was understood as a divinely given human duty and the wealth gained from it as a yardstick for divine grace. In addition to the economic upswing, this change in mentality resulted in restrictive poor legislation , which only allowed public support to be given to those in need who were considered unable to work. From 1563 onwards, the wealthy citizens were forced to maintain these poor people in the respective communal communities under threat of imprisonment. On the other hand, from 1576 at the latest, employable poor people were obliged to work with coercive measures. This led to the development of the workhouses , which were de facto mostly forced labor camps and were assigned to the arms even without having committed a crime.

In the 16th century, especially in its second half, there was a marked nationalization of English culture. The national character and the superiority of one's own country were emphasized in the literature, especially in historical and geographical works. Elisabeth often served as a projection surface for this understanding, which was particularly evident in the upswing in festive culture in connection with political events (throne anniversaries, birthdays, victory over the Armada).

The theater experienced a "golden age" , especially with William Shakespeare at the turn of the 17th century. The Renaissance in England was most clearly reflected in the acting . In this form of literature, the medieval theater is replaced by the orientation towards ancient models, whereby the self-determined and active individual comes into focus. From 1570 large, public theaters such as the Globe Theater were built, which gave the new dramas a broad impact. The sonnet emerged as another important form of literature .

In addition, the Elizabethan age was also extremely active musically. Instrumental and choral ensembles were formed at the royal court as well as at the courts of powerful nobles and in the big cities, and music was also made in middle-class households. Lutes and early keyboard instruments were particularly popular . The compositions mixed Italian influences with popular English music, especially in dances and madrigals .

Stuart era

Jacob I. - The unsuccessful reformer

Elisabeth's successor was Jacob I , the son of Maria Stuart , in 1603 . The 37-year-old had already gained rulership experience as King of Scotland and represented an unusually liberal stance on religious issues for his time, but an already absolutist understanding of rule based on the ruler's divine grace . The parliament, which in its time increasingly emancipated itself from the crown, met with rejection. From 1621 onwards, parliament used a new tool in the power struggle: impeachment . This was an indictment instrument that was occasionally used as early as the Middle Ages, with which the two chambers of parliament could conduct an extrajudicial process against royal officials in cooperation. In the same year the parliament also tried to enforce a basic right to deliberate on all state and church issues, but could not assert itself against the king. For the time being, the assembly remained subject to the king's specification of subjects. Parliament gained additional power because various court parties allied with it, depending on their current interests.

Jakob was also not very popular as a “Scot” among the population. The fact that, in contrast to Elisabeth, he kept an elaborate and expensive court and surrounded himself with Catholics and Spaniards made him even more unpopular. Various projects, such as the unification of England and Scotland, failed due to massive resistance in both countries.

His success in religious politics was similarly low. At the Hampton Court Conference in 1604, no fundamental agreement was reached with the Puritan movement. Jakob successfully countered demands for a renewed persecution of Catholics after the Gunpowder plot of 1605. Jakob promoted individual representatives of the emerging Arminianism , and he did the same with cooperative Puritans. The debts that Elisabeth had left grew significantly as a result of Jacob's sumptuous household, inflation and increasing tax evasion. Jacob's efforts to reform the tax system and thereby stabilize income failed in parliament. He was only able to alleviate the financial crisis by selling more nobility titles.

There was room for maneuver in Ireland . In 1607, after the end of the uprising supported by Spain, several Gaelic nobles fled into exile, including several counts. In the same year, James I moved in six of Ulster's nine counties and began redistributing the land to emigrants from England and Scotland. These population shifts were flanked by the expansion of the economy, church structure and a Protestant school system. Nevertheless, the Gaelic way of life was often adopted by the settlers. The Irish Parliament was also restructured and, in contrast to the English, mostly proved to be a supporter of the Stuart kings in the following decades. However, under Jacob the alienation process between the Stuart dynasty and their native Scotland began. The absence of the Westminster resident king meant that both the assembly of clan leaders and the newly formed Scottish Parliament became independent. In addition, the king could hardly influence the country through the Presbyterian and thus “from below”, ie from the community level, organized Scottish Church.

Immediately after taking power, Jacob ended the war against Spain. Then he tried to moderate the disputes between the denominations on the European continent through marriage negotiations over his daughter Elisabeth. But after Elisabeth had been married to Friedrich V of the Palatinate , Jakob threatened to be drawn into the outbreak of the Thirty Years War himself after the controversial election of his son-in-law . Ultimately, however, he limited himself to diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict. Also from 1604, Jakob conducted marriage negotiations for the heir to the throne Karl . After Elisabeth was married to a Protestant, the marriage negotiations for Karl quickly concentrated on the Catholic hegemonic power Spain, which was also interesting for England because of its wealth. However, Parliament refused to bind Spain because it feared a strengthening of Catholicism in England. The negotiations dragged on for years. After Charles traveled to Spain in 1622, the negotiations were officially ended and the heir to the throne advocated another war against Spain. Jakob finally consented to a campaign against the Palatinate occupied by Spain. In this difficult foreign policy situation, which was further complicated by a marriage contract with France, James I died in 1625.

Charles I - Wrestling with the Parliaments

Charles I resembled his father in some respects: he too was interested in art and science and ran a splendid court. Immediately after his accession to the throne, the intervention in the Thirty Years' War on the Protestant side, which he had previously propagated, began, but it quickly failed with a devastating defeat of the expedition to the Palatinate. Also in 1625 the marriage with the French princess Henrietta Maria, the daughter of Henry IV. , Was concluded.

The military failure in the Palatinate had caused considerable costs, which Karl tried to cover with taxes that Parliament, which had also called for entry into the war, was supposed to approve. The assembly refused to do so, however, and even further restricted the royal disposal of the customs revenue. In addition, it initiated an impeachment against George Villiers in 1626 . The king's favorite had failed as the commander of a fleet in an attack on Cádiz . Karl then dissolved parliament, but had to convene it again in 1628 because alternative attempts to finance the state through forced loans had hardly brought any income. The parliament ultimately granted the king the taxes, but was rewarded with a considerable expansion of his power: with the Petition of Right it enforced a right of initiative for laws for the first time ; previously it had merely approved or rejected royal laws. The petition itself contained a number of allegations against the king that he had exceeded his powers over traditional English law and the Magna Carta . By agreeing to the petition, Karl promised that he would refrain from doing this in the future. The following year there were disputes over the interpretation of the law, in the course of which the king dissolved parliament for eleven years. However, this did not change anything in parliament's gain in power at the expense of the crown.

Without a parliament and thus without approved taxes, not only was Charles I's financial leeway limited, but also his ability to act in foreign policy. Therefore, Charles quickly made peace with France and Spain. In the following years, domestic political tensions intensified. The king appeared to many subjects like his father as an absolutist ruler. In the eyes of the population, the legitimacy of royal rule without parliament was questionable. Above all, the in many cases actually arbitrary collection of additional taxes, which Karl urgently needed to rule without taxes, led to growing resistance, as did administrative reforms and the king's favoring of the Arminians . In addition, due to the marriage contract with Henrietta Maria, a strong Catholic party again emerged at court. From the king's point of view, Ireland in particular developed positively. The country flourished economically under the harsh reign of Thomas Wentworth . In 1641, however, the Gaelic resistance flared up again and quickly slipped out of the control of its leaders, around 12,000 Protestant settlers perished in the process. In Scotland, Charles I had already caused resentment among the nobles when he took office when he tried to revoke numerous privileges. Attempts to influence the Scottish Church caused a broad protest movement from 1637 onwards, which forced the king to convene a large church assembly. This declared all bishops deposed and raised their own army, which even invaded northern England in 1640.

With the war against the Scots began a serious crisis in the English monarchy. In order to finance the struggle in the north, Charles I had to convene a parliament again. Its members were not prepared to make any concessions because of their eleven-year elimination. After only one month, Charles dissolved parliament again in May 1640. In the summer the king could only end the Scottish invasion by agreeing to pay £ 850 a day pending a final peace. With this, the state finances finally collapsed. On November 3, 1640, the Long Parliament met, which should exist until 1660. Under the spokesman John Pym , parliament pushed through the removal and partial execution of royal advisors. Numerous royal privileges were abolished. Above all, however, Parliament fought for the right not to be dissolved without its own consent. Soon, however, overly radical demands led to a split in parliament. A royalist group emerged that was basically willing to negotiate with Charles I. In addition, public opinion, especially that of the London population, played an increasingly important role in the dispute between the King and Parliament. Violent clashes broke out, after which Karl left London in January 1642.

Civil war