Nine Years War (Ireland)

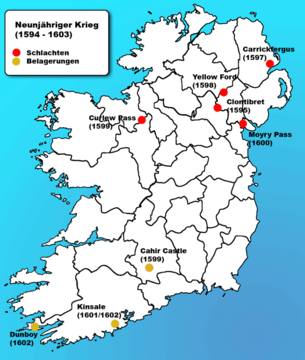

Clontibret - Carrickfergus - Yellow Ford - Curlew Pass - Cahir Castle - Moyry Pass - Kinsale - Dunboy

The Nine Years War ( Irish Cogadh na Naoi mBliain ) took place in Ireland from 1594 to 1603 and is also known as Tyrone's Rebellion (Irish Réabhlóid Thír Eoghain ). The armed conflict took place between the armed forces under the Gaelic - Irish clan chief Hugh O'Neill ( Earl of Tyrone ) and those of the Elizabethan English government of Ireland. The fighting extended across Ireland, but was mostly concentrated in the northern areas of Ulster . The war ended with the defeat of the Irish side, which eventually led to the flight of the Earls from Ireland ( Flight of the Counts ) and the Plantations in Ulster.

This Nine Years War should not be confused with the Irish War of the Two Kings from the 1690s or the War of the Palatinate Succession (1688–1697), which are often referred to as the “Nine Years War”.

Reasons for war

The causes of the Nine Years' War lay in the ambitions of the English government to expand the sphere of power to the entire Irish island and thus to keep the upper hand in the question of power. In order to oppose this plan, O'Neill managed to take advantage of the dissatisfaction with the English government in Ireland, also other clans as well as a large part of the Catholics (for whom the spread of Protestantism in Ireland was a thorn in the side) on his side bring.

The Rise of Hugh O'Neill

Hugh O'Neill comes from the powerful clan ( called Clan or Sept in English ) of Tyrone , who at the time were the dominant force in the center of Ulster province. His father was killed by Shane O'Neill and Hugh was driven from Ulster as a child. He grew up in the Pale and was considered a reliable lord by the English authorities. In 1587 he persuaded Elizabeth I to give him the title of Earl of Tyrone (Irish Iarla Thír Eoghain ) - the same title that his father held. But the real power in Ulster was not in this title, but with the head of the O'Neill clan (at that time Turlough Luineach O'Neill ). In 1595 - after much bloodshed - Hugh O'Neill had regained this title ("the O'Neill").

Within the O'Neill area, he tied the rural people more closely to his clan (he actually made them serfs ) and urged them to serve in the military. Of Red Hugh O'Donnell , one of his allies, O'Neill was supported by Scottish mercenaries (as Redshanks known). Furthermore, he hired large associations of Irish mercenaries (the so-called buanadha ) - partly under the leadership of Richard Tyrell. To arm his army, O'Neill bought muskets , ammunition and pikes from Scotland and England. Since 1591 O'Donnell (on behalf of O'Neill) was in contact with Philip II of Spain in order to campaign for military support against England and against the spread of Protestantism. With the help of Spain , O'Neill was able to arm and feed over 8,000 men. He was well armed against the advance of English troops in the Ulster area.

English troops in Ulster

In the early 1590s the province of Ulster came under the spotlight of Lord Deputy Fitzwilliam, who was entrusted by the English crown to bring the area under control and to set up a kind of provincial government - the most promising candidate for this post was Henry Bagenal, an English colonist Newry , who wanted to enforce English rule through an increased military presence. O'Neill was married to Bagenal's sister (against his will), but she died a few years after the wedding.

In 1591 Fitzwilliam conquered the MacMahon lordship in Monaghan . MacMahon defied an English sheriff and was hanged. His lands were divided - this led to resistance as allegations of corruption were raised against Fitzwilliam; but the same practice was used in Longford (O'Farrell area) and Cavan (O'Reilly area). In the O'Neill area, however, Fitzwilliam now expected a strong armed army that would oppose any attempt to take the area.

Probably the greatest difficulty the English forces had in conquering Ulster lay in the natural features of the landscape. Due to the mountain ranges, forests and marshland, there were only two sensible places for British troops to advance into the O'Neill area: Newry in the east and Sligo in the west. Sligo Castle was occupied by the O'Connor clan, but was in constant danger of being attacked by the O'Donnells. The route via Newry, on the other hand, led through various valleys which, in the event of a war, could only have been held by the English troops through enormous investment of money and human lives.

The English troops had a base at Carrickfergus (north of Belfast Lough ), where a small colony of English settlers was established in the 1570s. But even from here the area offered a natural border to the O'Neill area through Lough Neagh and the River Bann . Another difficulty lay in the fact that the English troops did not control any ports on the northern coast that would allow an attack from the sea.

Outbreak of war

In 1592, Red Hugh O'Donnell drove the English sheriff Captain Willis from his area Tír Chonaill . In 1593, Maguire and O'Donnell allied to oppose the introduction of Willis as sheriff of Fermanagh. They also began attacking the English outposts south of Ulster.

O'Neill stayed in the background of the clashes up to this point, hoping to be named Lord President of Ulster through this reluctance . Elizabeth I, however, suspected that O'Neill would have no interest in such a simple title. Instead, she feared that O'Neill was seeking more power to subvert her authority and rule as a kind of "Prince of Ulster". Because of this, she denied O'Neill the title - as well as any other title that would have given him authority over Ulster in the name of the Crown. When it became clear that Henry Bagenal would receive the title of Lord President of Ulster , O'Neill intervened and raided an English fort on the Blackwater River .

Victory on the Yellow Ford

Even after the English defeat at the Battle of Clontibret in March 1595, the English authorities in Dublin found it difficult to understand the depth of this rebellion. After failed negotiations in 1596, English troops attempted to invade Ulster, but were easily routed by a well-established army of musketeers.

At the Battle of Yellow Ford in 1598, nearly 2,000 English soldiers were killed in an ambush while English troops marched towards Armagh . The surviving soldiers were surrounded in Armagh, but they were able to negotiate a safe retreat and in return left the city without a fight. O'Neill's personal enemy , Henry Bagenal, led these forces but was killed at the start of the battle. This battle was the greatest defeat England had suffered in Ireland up to that point.

The victory sparked rebellions across the country, aided by O'Neill's mercenaries. Hugh O'Neill bestowed Earl and Chieftain titles on his supporters, such as: B. James Fitzthomas as Earl of Desmond or Florence MacCarthy as MacCarthy Mór . In Munster nearly 9,000 men took part in the rebellion. The English plantations were largely destroyed and the English settlers, including Edmund Spenser , fled to safer areas.

Only a handful of resident lords remained loyal to the English crown during this period, and even among its followers there were supporters of the rebels. But all fortified cities remained in the hands of the English authorities, and O'Neill did not succeed in capturing them or in drawing their people to his side.

In 1599 Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex , reached Ireland with an army of 17,000 men. He accepted the recommendation of the State Council to bring the south of the country under control first, but his haphazard approach dispersed his units so much that he suffered various setbacks on his advance into Leinster and Munster . The climax of the setbacks in the south of Ireland was the attempt to get over the Curlew Mountains to Sligo - a quarter of the English soldiers were killed in the battle of Curlew Pass , while the men around O'Donnell suffered almost no losses.

Thousands more men from Devereux's troops were housed in filthy garrisons and died of typhus and dysentery .

When Devereux finally turned to Ulster , he immediately began peace negotiations with O'Neill and agreed to a truce, which was heavily criticized by his enemies in London . In order to forestall a recall to London, Devereux traveled back without the consent of the Queen, where he was executed after an attempted coup. His successor in Ireland was Charles Blount, 1st Earl of Devon ( Lord Mountjoy ), who proved to be a far more capable commander. At his side, the two war veterans George Carew and Arthur Chichester, 1st Baron Chichester, were given high command in Munster and Ulster.

The end of the rebellion in Munster

Carew managed to bring the rebellion in Ulster more or less under control by mid-1601. In the summer of 1601 he had retaken most of the castles in Munster and the rebel troops were dispersed. Fitzthomas and Florence MacCarthy were arrested and spent the rest of their lives in the Tower of London .

The Battle of Kinsale and the End of the Rebellion

Mountjoy, supported by landing forces, was able to penetrate inland from Ulster by sea (under Henry Dowcra at Derry and Arthur Chichester at Carrickfergus ). Dowcra and Chichester, aided by Niall Garve O'Donnell , a rival of Red Hugh , ravaged the countryside, killing indiscriminately among civilians. Their strategy was that without crops and humans, O'Neill could not get supplies and also could no longer feed his armies. These atrocities quickly began to work, and so the lords of Ulster were set in their territories to defend them. Although O'Neill was able to repel Mountjoy's offensive near Newry at the Battle of Moyry Pass in 1600 , his position became more and more hopeless.

In 1601 the long-promised Spanish support (3500 men) near Kinsale ( County Cork ) finally reached Ireland. Immediately after landing, the Spanish troops were surrounded by 7,000 English soldiers who, however, were weakened by hunger and disease. O'Neill, O'Donnell and their allies decided to come to the aid of the Spanish troops and made their way south. On December 24th, O'Neill and O'Donnell attacked the English troops. But due to poor coordination and a lack of experience, the two could not take advantage of their surprise effect and were ultimately defeated by an overwhelming British force in the siege of Kinsale .

The rest of the Irish troops fled back to Ulster to defend their own lands, but more men died from the cold than in the actual battle. The last rebel-occupied stronghold in the south of the island was captured by George Carew during the siege of Dunboy Castle in June 1602 . Red Hugh O'Donnell left Ireland to seek further support in Spain, albeit in vain. He died there in 1602. His brother Rory stayed in Ireland to defend Tír Chonaill . Rory O'Donnell and Hugh O'Neill used guerrilla tactics to fight in small groups against the forces of Mountjoy, which had already penetrated far inland from Ulster.

End of war

With the destruction of the inauguration stone in Tullaghogue , Mountjoy symbolically sealed the end of the O'Neill clan. Due to the scorched earth tactics , a famine soon struck Ulster. Thereupon O'Neill's subordinate Lords O'Hagan, O'Quinn and MacCann surrendered. Rory O'Donnell, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell , surrendered at the end of 1602. O'Neill was able to hold his secret base in the dense forests of Tír Eoghain until March 30, 1603, before he too surrendered (though not unconditionally). Elizabeth I died a week earlier.

Aftermath

The rebels received astonishingly large concessions for their surrender from the new English King James I. O'Neill, O'Donnell and the other surviving lords of Ulster received full pardons and their lands back. However, they had to give up their Irish titles, their private armies and control over their former serfs, as well as swear an oath of allegiance to the English crown. In 1604, Mountjoy issued a pardon for all rebels in Ireland. The background to these far-reaching concessions on the part of the English was that they could not afford to continue the war in Ireland. Elizabethan England had no standing army , nor was the English parliament prepared to spend more tax money on protracted wars, since England was also involved in the war in the Spanish Netherlands . The war in Ireland, which had cost over two million pounds, had almost led to the British state becoming insolvent.

Irish sources estimate that up to 60,000 Irish people died in the 1602–1603 famine. Even if this number cannot be proven, it is now believed that up to 100,000 Irish people died during the entire period of the war. At least 30,000 people died on the English side, most of them from disease or epidemic.

Although O'Neill and his allies had got out of the conflict very lightly, an insurmountable distrust of the other remained on both sides. O'Neill, O'Donnell and the other Gaelic lords of Ulster left Ireland on the Flight of the Earls in 1607 when the new Lord Deputy of Ireland , Arthur Chichester, 1st Baron Chichester , began restricting the freedoms of the two Earls in 1605 . Both feared imprisonment, and since Ireland was now completely under English control again, both ultimately decided to leave the Irish island for the European continent. They planned to start another war in the future with the help of other Catholic forces, but could not get any support. Their lands in Ireland were confiscated after their escape and colonized with English settlers. The Nine Years War is therefore an important step in the English settlement of the north of the Irish island.

See also

Literature (all in English)

- John O'Donovan (Ed.): Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland, by the four masters, from the earliest period to the year 1616. Edited from Mss. In the library of the Royal Irish Academy and of Trinity College, Dublin, with a translation, and copious notes. 7 volumes. Hodges, Smith and Co., Dublin 1851-1856.

- John Sherren Brewer, William Bullen (Ed.): Calendar of the Carew manuscripts preserved in the Archiepiscopal Library at Lambeth. = Calendar of State Papers. Carew. 6 volumes. Longmans, Green & Co., London 1867–1873.

- Richard Bagwell: Ireland under the Tudors with a succint account of the earlier history. 3 volumes. Green and Co., London 1885-1890.

- Thomas Stafford : Pacata Hibernia. Or a history of the wars in Ireland during the reign of Queen Elizabeth. Especially within the province of Munster. Edited and with an introduction and notes by Standish O'Grady. 2 volumes. Downey & C., London 1896.

- Cyril Falls: Elizabeth's Irish Wars. Methuen, London 1950 (Reprint. Constable, London, 1997, ISBN 0-09-477220-7 ).

- Steven G. Ellis: Tudor Ireland. Crown, Community and Conflict of Cultures, 1470-1603. Longman, London et al. 1985. ISBN 0-582-49341-2 .

- Hiram Morgan: Tyrone's War. The Outbreak of the Nine Years War in Tudor Ireland. (= Royal Historical Society Studies in History 67) Boydell Press, Woodbridge et al. 1993, ISBN 0-86193-224-2 .