Anointing

The anointing (to anoint "with an ointment ") is a religious ritual of healing, sanctification and the transfer and legitimation of political power, documented since the time of the ancient oriental empires .

Following the example of the biblical kings , the ordination rite of anointing has been a decisive act of the elevation of the king , which took place before the coronation , in many European countries since the Middle Ages . To this day, the anointing is part of several sacraments and sacramentals of the Catholic Church . The anointing is also practiced in the Orthodox as well as in various Protestant churches .

Origins

The use of mostly fragrant anointing oils or balms for care and healing purposes was already known in the ancient oriental cultures of Mesopotamia and Egypt . As a rule, it was only available to the wealthy, as it was usually precious and sometimes - as archaeological finds from Egypt and Babylonia show - in equally precious vessels, e.g. B. made of glass, was kept.

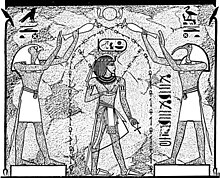

The advanced civilizations in the Fertile Crescent were also familiar with anointing rites that went beyond the healing and caring use of the oil. In Sumer , Akkad and Babylon , they were used as legal acts in the appointment of priests and officials. The Egyptian pharaoh anointed his highest minister as a sign of the transfer of power. The anointing of the kings of Israel mentioned in the Old Testament probably goes back to this model.

In biblical times

Old testament

As a means of sanctification, i.e. for the ordination of priests , prophets and sacred objects, an anointing oil is described for the first time in the Book of Exodus ( Ex 30,22–33 EU ). It had to be made from myrrh , frankincense , cinnamon , calamus and cassia . These aromatic plant components were mixed in olive oil , which absorbed their scent. Such anointing oil, which could only be used for sacred purposes, is also mentioned in Psalm 133:

- “See how good and how beautiful it is when brothers live in harmony with one another. It is like delicious anointing oil on the head, which flows down on the beard, the beard of Aaron, which flows down on the hem of his garment ”( Ps 133,2 EU ).

The Hebrew term Mashiach or Messiah ("the anointed") denotes various holy persons or things in the holy scriptures of Judaism (Old Testament):

- Moses brother Aaron and his sons in their function as priests ( Ex 30,22-33 EU )

- the tabernacle with the ark , the altar of burnt offering and all liturgical devices ( Ex 30.22 to 33 EU )

- the tent of revelation ( Ex 40.9 EU )

- Jewish priests ( Lev 4,3 EU ) and prophets ( Isa 61,1 EU )

- unleavened bread ( Num 6.15 EU )

- as well as the Persian king Cyrus II. ( Isaiah 45.1 EU ), of the return of the Israelites in exile Judea allowed

The ritual anointing of a king first appears in Book 1 of Samuel . They report the prophet Samuel had Saul as the first king of Israel anointed ( 1 Sam 10.1 EU ). The ritual, which was also performed on Saul's successors, David and Solomon , was intended to give the ruler divine grace and a prominent status among men, but also to show him that he in turn owes his power to God.

The eschatological expectation of salvation in Judaism was directed towards the restoration of the Old Testament kingship through the arrival of a future savior, as he did, for example. B. is described by the prophet Jeremiah ( Jer 23,5 EU ). As Maschiach , anointed one, he was already mentioned in the Psalms of David (around 1000 BC) ( Ps 2 : 1–8 EU ). The Hebrew term Maschiach was used from around 250 BC. In the Koine - Greek translation of the Old Testament, the Septuagint , translated into Greek ("Christós") and later Latinized in "Christ" (cf. among others the Vulgate ).

New Testament

In the New Testament , Jesus of Nazareth is identified as the anointed one by the words “Christ” or “ Messiah ” . The latter is a not entirely correct transliteration of the Hebrew Maschiach that has changed in meaning . According to New Testament statements, for example in the Acts of the Apostles ( Acts 4,25-27 EU ), which refer to prophecies of the Old Testament (e.g. in Jer 23,5 EU , Isa 52,13ff EU , Dan 7,13-14 EU , Isa 9,5–6 EU , Ps 2,1–8 EU ), the early Christians already saw in Jesus a descendant of David and the redeemer and anointed of the end times awaited by the Jews , whose second coming and future kingdom was imminent.

The name Jesus Christ expresses the creed of the early Christians : for them Jesus was the anointed of God, whose deeds and signs (e.g. Jn 9 : 1–34 EU ), in addition to the prophecies, confirmed the institution and authorization by God. The Evangelist John remarks in Jn 20 : 30–31 EU :

“Jesus did many other signs before the eyes of his disciples, which are not recorded in this book. But these are written so that you might believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that through faith you may have life in his name. "

Anointing as a sacramental of the ruler's ordination

Based on these biblical models, the Christian kings of Europe had themselves anointed at their coronation since the early Middle Ages . The first known anointing of the king was that of the Visigothic ruler Wamba in the year 672. The emperors of the Byzantine Empire followed this custom since around the year 1000, but only since the 13th century . The new ruler was then regarded as Christ Domini , the “anointed of the Lord”, who received his rule not from people but from God himself. The anointing thus clarified the idea of the divine right of rulers and was therefore the most important ritual at the coronation of kings in the Holy Roman Empire as well as in France, England and most other kingdoms of the West .

In the Frankish Empire and in France

The ritual had a long tradition in France , probably going back to the Frankish times. In the cathedral of Reims , the coronation church of the French kings , the holy ampoule was kept until the French Revolution , a vial of anointing oil which, according to legend, a dove from heaven to earth for the baptism of the Merovingian king Clovis I in the year 496 or 499 should have brought.

In fact, Pippin the Younger , the father of Charlemagne, was probably the first ruler to be anointed King of the Franks . The first Carolingian on the throne had deposed the last Merovingian with the consent of the Pope, but possibly required a visible sign of legitimacy for his coronation in 751. This is precisely what the new sacraments of anointing might have served. It made it clear that the new king was chosen by God himself. Over time, this idea of divine right displaced the earlier idea of the salvation of kings, which could be passed on to the ruling dynasty under the Merovingians solely through blood rights .

It has been proven that the anointing took place at all royal coronations in French history since the time of the early Capetians . Before the Archbishop of Reims presented the actual regal insignia such as crown , scepter and imperial sword to the king to be crowned , he rubbed a few drops of this holy oil on his chest with his right thumb, which had previously been mixed with chrism on a paten . He spoke the ritual formula "Ungo te in regem" ("I anoint you to be king"). The fusion of anointing oil and chrism underscored the double sacredness of the French king.

In the Roman-German Empire

At the coronation of the Roman-German kings and emperors , the monarch kept an undergarment on during the anointing, which had openings over the body parts to be anointed. The coronator ("König crowner") - usually the Archbishop of Cologne, in whose archdiocese the original coronation city of Aachen was located - anointed the future king on the head, chest, neck, between the shoulders, on the right arm, on the joint of the right arm and on the inner surface of the right hand with the words: "I anoint you king in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit". Then two auxiliary bishops dried the anointing oil with cotton and rye bread. Like the French king, the Roman-German king was only then put on the coronation robes and the imperial insignia presented.

In England

The only royal anointing that is still in use today takes place at the coronation of British monarchs in Westminster Abbey . The English coronation liturgy stipulates that it should take place after the enthronement - on the coronation chair of Edward I - and before the ruler's insignia is presented and the crown is erected. The new monarch takes off his purple robe beforehand and is dressed in an alb . As soon as he is seated on the throne, the Dean of Westminster pours consecrated anointing oil from a vial into a spoon held by the Archbishop of Canterbury . This now anoints the new king or queen on the hands, chest and head. For the duration of the anointing four hold Knights of the Garter a canopy over the new rulers. This part of the coronation was still considered so sacred in 1953, at the coronation of Elizabeth II , that it was not televised.

Sacred meaning

The anointing as a sacramental at the coronation gave the kings a spiritual meaning in addition to their worldly power. As a result of the ecclesiastical reform ideas , which had given the priesthood priority over the principality since the 11th century , the spiritual significance of the anointing became increasingly secondary in the 11th century. In the Caeremoniale Romanum of 1516 it is said that the cardinal deacon only has to anoint the future emperor on the elbow of his right arm, the sword arm, with catechumen oil . This rite was used in Bologna in 1530 during the anointing of Charles V , the last, imperial coronation , carried out by the Pope himself.

Nevertheless, ideas of the divine right of kings nourished from the anointing for Christ Domini . Moreover, the idea was connected to the anointed monarchy in France and England, they grant the king the power to the Skrofeln to heal sick people by merely laying. The ritual of the anointed king touching the sick was practiced in England until the 18th century, and in France until 1825, when Charles X performed it for the last time. In the Middle Ages, it was seen as a means to demonstrate the legitimacy of the king, since it was assumed that only the true king had the healing powers.

Anointing in the churches

In the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church has an anointing in four of its seven sacraments :

- The anointing of baptismal candidates before baptism with catechumen oil and after baptism with chrism

- The anointing at confirmation with chrism

- The anointing of priestly ordination and episcopal ordination with chrism

- The anointing of the sick . This sacrament is given to the sick and dying and is intended to bring them strength and comfort. Furthermore, the anointing is supposed to make the suffering in faith an image of the suffering Christ ("anointed"). The sacrament is traced back to a passage in James ( Jak 5,14-15 EU ) in which the sick of the community are asked to call the elders ("presbyters") of the community so that they intercede for them and they " anoint with oil in the name of the Lord ”.

In addition, the Catholic Church practices the anointing of some sacramentals such as the consecration of a church, an altar or that of a chalice .

In the orthodox churches

In the Orthodox churches, too, the administration of some sacraments is accompanied by an anointing

- The anointing with Myron which is confirmation and takes place immediately after baptism

- The anointing of the sick , which in the Eastern Churches has always been supposed to serve healing rather than preparation for death. In its solemn form it is supposed to be donated by seven priests, which, however, rarely happens. In addition, as part of the annual preparation for Easter , the sick oil is also donated to physically healthy people in order to help them with the "sickness" of sins .

In the Evangelical Church

For a long time, the anointing of the sick was hardly practiced in the Protestant Church , which mainly focuses on the preaching of the word. As a result of the ecumenical movement, however , it has recently been increasingly used there again.

In the free churches

Many free churches, such as the Evangelical Free Churches ( Baptists ) or the Free Evangelical Churches , practice the anointing of the sick. This prayer service, which here belongs to the area of responsibility of the elders of the congregation, usually runs as follows: The sick person asks for this service or has the elders called. After a short discussion and mutual confession of possible sins ( Jak 5,16 EU ) the elders lay their hands on the sick person and anoint him symbolically in the name of Jesus Christ with oil. This is followed by free intercessory prayers by the elders, in which the suffering and wishes of the sick are named as specifically as possible. The anointing of the sick is often concluded with Psalm 23 , which is prayed together and which also speaks of the anointing by God ( Ps 23.5b EU ).

In the charismatic movement

The charismatic movement very often uses the term "anointing" in a figurative sense. While oil is seldom anointed, within the charismatic movement the sacred atmosphere in a congregation or the divine authority inherent in a pastor , preacher or leader is called "anointing." According to this understanding, it is synonymous with the presence and work of the Holy Spirit .

literature

- Jean-Pierre Bayard: Sacres et couronnements Royaux. Guy Trédaniel, Paris 1984, ISBN 2-85707-152-3 .

- Marc Bloch : The Miraculous Kings , CH Beck Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-47519-1

- Alain Dirkens: Coronation, anointing and royal rule in the Carolingian state and in the states following it. In: Mario Kramp (Ed.): Coronations. Kings in Aachen - history and myth. Two volumes, Zabern, Mainz 2000, Vol. I, pp. 131–140.

- Kenneth E. Hagin: The anointing , breakthrough Verlag Augsburg, 4th edition March 2006, ISBN 3-924054-14-2

- Ernst Kutsch: Anointing as a legal act in the Old Testament and in the Old Orient , supplements to the journal for Old Testament science, ed. by Georg Fohrer, No. 87, Berlin 1963

- Josef J. Schmid: Rex Christ - the tradition of the French monarchy as a bridge between East and West (5th – 19th centuries). In: Peter Bruns / Georg Gresser (eds.): From the Schism to the Crusades: 1054–1204. Schöningh, Paderborn 2005, ISBN 3-506-72891-1 , pp. 205-234.

- Josef J. Schmid: Sacrum Monarchiae Speculum - the Sacre Louis XV. 1722: monarchical tradition, ceremonial, liturgy , Aschendorff, Münster 2007, ISBN 3-402-00415-1 .

Web links

- Anointing in the Evangelical Church ( Memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive )