Franconia (people)

The Franks (meaning "the brave, bold") were one of the great Germanic tribes . They were formed in the 3rd century in the area of the part of Germania occupied by the Romans through alliances of several small tribes.

The Franks (Latin Franci ) were first mentioned in contemporary sources in 291 in a Panegyricus to the emperors Diocletian and Maximian . Around 360/61 the late ancient Roman historian Aurelius Victor reported in his imperial servants that the Franks (Francorum gentes) had already devastated Gaul at the end of the 250s . Salian Franks (also known as Salians) and Rhine Franks initially expanded spatially separately - the Salians via Toxandria to Gaul, the Rhine Franconians via the Middle Rhine and the Moselle area to the south and into the former Roman province of Gallia Belgica on the left bank of the Rhine . Frankish warriors served the emperor as foederati in the 4th and 5th centuries , before they founded the most important Germanic-Romanic successor empire in the west in the transition from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages , where the last western Roman emperor had been deposed in 476. The Merovingian Clovis I united the sub-associations of the Sal Franconians and Rhine Francs for the first time around 500 and created the Franconian Empire , which experienced its greatest expansion under the Carolingian Charlemagne .

Franconia and the local population mixed linguistically and culturally over the course of time. In the west the Gallo-Roman language dominated , in the east the Franconian language , between them a language border developed up to the 9th century . Most of the Salfranken later merged in the French and Walloons . The Salfranken on the IJssel and Niederrhein as well as the Moselle and Rhine Franconians retained their Franconian dialects until modern times and were absorbed by the Germans , Dutch , Lorraine , Luxembourgers and Flemings . The modern region of Franconia historically formed the eastern settlement area of the tribe. Its inhabitants are still referred to as Franks today.

Under the grandchildren of Charlemagne, the great Franconian Empire was initially divided into three. The middle Kingdom of Lorraine was divided between Eastern and Western France in 870 . The successor states of Germany , the Netherlands , Belgium and Luxembourg , as well as Switzerland , Liechtenstein , Austria , parts of Italy and east-central European border areas emerged from the East Franconian Empire (later the Holy Roman Empire ) . The successor state France emerged from the West Franconian Empire .

The name of the Franks

The ethnonym of the Franks is - like the names of other Germanic tribes - as a source with great proximity to historical events of importance for modern history . In the contemporary historical representations, mostly written in Latin, the ethnonyms remained as Germanic “foreign bodies” and were therefore relatively little influenced by the respective interpretation of the author; The same applies to the evidence of Germanic personal names.

In principle, the question of external or self- naming also arises for the interpretation of the Franconian name; A well-known example is the ongoing discussion of the Germanic term. The name of the Franks follows a common motif in Germanic tribal names after a characteristic peculiarity or property based on observation from the outside or one's own perspective.

The more recent naming system follows the reference work of the early medieval scholar Isidore of Seville (around 560–636) and traces the Franconian name to an Indo-European root * (s) p (h) ereg - "greedy, violent". The root also brought out Greek σπαργάν "swell, bristle, violently desire" and led, especially in the Germanic area, to the rich family of words from Old Norse frekr "greedy, hard, strict" - of which Old Norwegian frakkr "fast, courageous" and synonymous Swedish (dialect) fräk -, Middle Dutch vrec "greedy, greedy, hard-hearted" (from Dutch vrek "Geizhals"), Old High German freh "greedy, greedy, ambitious" (eighth century), Middle High German vrech "courageous, brave, brash" and New High German cheeky and Old English naughty "Greedy, eager, bold" and freca "bold man, warrior", from which the synonymous freak in modern English. The Franconians were called the "greedy, ambitious, brave, bold".

The meaning of the New High German frank in the sense of 'free', however, arose at the time of the Merovingians in the Romanized territory of the Franks and is probably based on the tribal name. In contrast to the Roman or Gauls , 'the Frankish man' was simply 'the free one', from which franc as a noun and franc as an adjective. It was not until the 15th century that the German meaning “free” was borrowed from French.

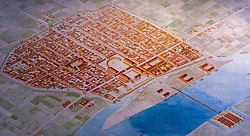

The location on the Lower Rhine Limes

At the turn of the century, the Lower Germanic Limes was the border between the Roman province of Germania inferior on the left bank of the Rhine and the barely controlled Germania Magna on the right of the Rhine. This Limes section, beginning around today's Bad Breisig and ending in the area where the Old Rhine flows into the North Sea, was primarily determined by the course of the river itself, less by ramparts or walls. Roman forts and fortifications stretched along the river via Nijmegen , Xanten , Neuss , Cologne to Bonn , where the Upper German Limes began a little up the Rhine . In this protection zone, a large number of Roman country estates ( Villae Rusticae ) and settlements ( Vici ) were built in the hinterland to the left of the Rhine ; The imperial city of Trier functioned as an important symbol of Roman power in the Gallo-Roman-Germanic border region .

In the large area between the Rhine and the Ardennes , however, there were also Germanic villages and settlements that lived in dependence on the Roman institutions. The Germans who settled to the right and left of the Rhine were thus familiar with Roman culture, civilization and military technology; Teutons were active in the service of the Romans to varying degrees, not infrequently as military alliance troops. The tribe of the Ubier was founded by the Romans around 15 BC. Settled in today's Cologne and gradually Romanized - this also applied to the Batavians in the Dutch Betuwe . There were repeated raids by Germanic groups against Roman institutions, which could also spread to larger disputes.

Rome's internal problems with secondary emperors and counter-emperors in the 3rd century (see Imperial Crisis of the 3rd Century ) had a destabilizing effect on the situation in Gaul and Germania. Later came the unrest of the beginning of the migration period and the clashes of the Romans with Goths and other Germanic tribes. That was the period in which the Germanic groups and tribes of the Germania Magna on the right bank of the Rhine first formed action communities, then tribal alliances and finally new peoples - this applies to the Franks as well as to the Saxons , Alemanni , Thuringians , Bavarians and Burgundians .

The Franks before the Francs

The (proto) Franconian tribes and associations initially settled to the right of the Rhine, often changed their settlement area and repeatedly pushed forward to raids into Gallo-Roman territory. Although the delimitation of the sub-tribes from one another and from other Germanic tribes is sometimes fraught with uncertainties, the Franconian tribes appeared to the Romans as a linguistic and ethnic unit that went beyond the narrower tribal name.

The “inner perception” of the tribes among themselves was initially more differentiated. At first they only formed loose alliances, as they were suitable for raids or defensive measures. From this "tribal swarm" a tribal association or tribal union emerged in the course of time (according to customs officers this is definitely to be mentioned) and only in the course of time the people. In recent research (Patrick Geary, Michael Kulikowski and others) it is increasingly assumed that the merger of the Franks was initially promoted by the Romans, who wanted to bring the Limes foreland under control in this way.

When the Imperium Romanum went through a phase of weakness in the 3rd century, the Franks, Alamanni and Saxons used this for raids. The first known Frankish forays into Roman territory took place in 257/59 and increased steadily in the period that followed. The mention of these first Frankish raids can only be found in a later late antique source in Aurelius Victor (around 360); the first mention of the Franks in a contemporary source can be found in a Panegyricus from the year 291. When the Roman Empire had stabilized again, many Franks served in the Roman military and some rose to high positions. The expansion of the Franks from the north-west and east across the Rhine created a certain pull for the following Germanic tribes ( Frisians , especially Saxons, also Thuringians), which always ensured points of contact, combat operations, but also cross-tribal small alliances.

In a Roman road map from the middle of the 4th century - the Tabula Peutingeriana - the "Francia" (the land of the Franks) on the right bank of the Rhine was already explicitly recorded.

Whether one can speak of Franconian “tribes” at this time is controversial; some scholars (Guy Halsall et al.) view the factions more as mercenary troops. The Franconian ethnogenesis was in any case a process that dragged on over a longer period of time. When the development towards a common “popular feeling” was completed cannot be precisely determined historically; During the time of the initially spatially separated actions of the Salfranken and Rheinfranken, there was always contact between the associations and joint actions against common enemies. It was therefore easy for the Merovingian Clovis I in the year 509, after the elimination of the Ripuarian rex Sigibert of Cologne, to also head the Association of Rhine Franks, because they saw him, like themselves, as a "Franconian".

The subgroups of the Franks

In the founding phase of the Confederation of Franks in the 3rd century, the groups settling in the north-west and on the Lower Rhine had come together; The Salfranken Association was formed from the groups that settled from the Lower Rhine to Salland on the IJssel. The groups settled as foederati from the greater Cologne area across the Middle Rhine and south of it to the Lahn were gradually absorbed into the Rhine Franconia and the Moselle Franks descended from them .

The early Franks were probably primarily warriors from the tribes of the Istaevonen group. These included:

- Salfranken or Salier: with the subgroup of the Tuihanten . The Salians lived from the Lower Rhine to the Salland (on the IJssel) and took in neighboring tribes. They became the main tribe of the Franconian expansion and from them the ruling house of the Merovingians emerged.

It is most likely that those groups who settled from the mouth of the Rhine to the Lower Rhine (including the Sugambrers and Cugernians) joined the Salians, while the groups from the Cologne area to the Lahn valley (from the Brukterians to the Usipeters) joined the Salians the Rhine and Moselle Franconia rose. These "tribes" are listed below in the approximate order of their settlement areas from the mouth of the Rhine up to the Lahn:

- Chattuarier : were based on the upper (Dutch) Lek, individual groups penetrated deep into Gaul in the "Hatuyer".

- Chamaver : first settled north of the Lippe, penetrated to the Meuse in the 4th century.

- Tubanten : settled in the east of today's Netherlands and in the area of today's districts of Borken and Steinfurt .

- Sugambrer : (also Sigambrer or Sicamber) with the subgroup of the Cugerner on the left bank of the Rhine in the area of Xanten to Krefeld. The name of the Sugambres was occasionally used by ancient scribes instead of the Franks. Even at the baptism of Clovis I (between 497 and 499), Bishop Remigius of Reims spoke the words:

- “Now bow your head , proud Sicamber, and submit it to the gentle yoke of Christ!

- Worship what you have burned so far and burn what you have worshiped so far! "

- Brukterer : already mentioned in Tacitus , first settled on the Ems and Lippe, participated in the conquests of Cologne and Trier and settled there.

- Tenkerer : originally east of the Rhine, later advanced to Sieg.

- Usipeter : often referred to in connection with the Tenkers, later settled in the Lahn valley.

Groups of the Ingwäons also joined the Franks, including the

- Ampsivarians : mentioned by Tacitus as the southern neighbor of the Frisians ; Displaced by the Chauken from their home areas on the Ems, they migrated to the Lower Rhine.

- Chauken : (whose epic name is assumed to be "Hugen" in the Beowulf legend). They settled as neighbors of the Saxons, in whom most of them were absorbed. A part probably joined the Franks.

The following were only partially involved in the genesis of the Franks:

- Batavians : already Romanized at the time of the formation of the Franks, their descendants were absorbed by the Salians.

- Ubier : in the Cologne area as early as 18 BC BC settled on the left bank of the Rhine by the Romans in the oppidum ubiorum , already Romanized at the time of the formation of the Franks. After the conquest of Cologne, their descendants were absorbed into the Rhine Franconia.

- Chatting : settling on the upper reaches of Eder , Fulda and Lahn (namesake of the later Hessians ). They were an independent tribe that came under Franconian sovereignty in the course of the Franconian expansion and mixed with the Franconian settlers advancing to the southeast.

- Thuringian : (and scattered small groups of other Germanic tribes) who had occasionally penetrated to and across the Rhine and settled there. A "small kingdom" of the Thuringians on the left bank of the Rhine is also mentioned, although this has recently been controversial. These settlers - in contrast to their tribal peoples who remained to the east - were absorbed into the Franks.

Further groups settling in the expansion area of the Franks were integrated by the Franks. As far as these groups settled in today's German-speaking or Dutch-speaking areas, they were absorbed by the Franks. In today's French-speaking areas, the process was reversed: the Franks merged there with the local Romansh population in later centuries:

- Roman settlers who had not fled south from the advancing Teutons

- Germanic tribes settled by the Romans in the Gallia Belgica, who were predominantly Romanized at the time of the Franks genesis

- scattered remnants of Celtic (and Celtic-speaking) population in the area between the Rhine, Eifel / Ardennes and Scheldt

- Gallo-Romans (Romanized Celts), the majority of the population left of the Rhine before the Franconian expansion.

Salier and Rhine Franconia

Salier

The process of the emergence of the Franks from various smaller sub-tribes took place over a longer period in the 3rd century. In the year 294, Constantius I , elevated to the rank of emperor, expelled groups called Franks from the "Batavia", the former Bataverland in the Betuwe . Some of those who remained were settled as Laeten (semi-free) on Roman territory. In 358, Sal-Franconian groups crossed the Rhine to the southwest and invaded the Roman Empire via the Betuwe . The Romans were able to successfully defend themselves against the Frankish advances. The later emperor Julian (at that time still Caesar , i.e. lower emperor, under Constantius II. ), Allowed the Salians to settle in Toxandria , a sparsely populated area within the Roman province of Belgica II at the time. In return, the Frankish warriors stood there in the military service of the Romans. A testimony to this event and for the name of the Salians can be found in the historian Ammianus Marcellinus , who writes about the battles of Emperor Julian:

"... he turned against the Franks first, namely against those who are usually called Salians."

The Salfranken remained in Toxandria until the beginning of the 5th century, before they penetrated further south and gradually conquered Gallo-Roman lands. Childerich I laid the foundation by establishing a position of power in northern Gaul in the 460s and 470s of the 5th century. His son and successor Clovis I conquered several small Frankish empires and finally, in 486/487, the small empire of the last Roman ruler in Gaul Syagrius . This ended the Roman rule in Gaul. In the time from Clovis, the Merovingians made use of the knowledge of the old Gallo-Roman elites .

Whether the Salians had their tribe name at the beginning of the Franconian genesis and then part of them set off from the Lower Rhine to Salland (on the IJssel), or whether their proto-tribe moved to Salland together with other groups and were called "Salier" from then on is unclear among historians. What is undisputed, however, is their key role in the Frankish expansion; the Merovingian King Clovis I laid the foundation stone for the later Franconian Empire by uniting the Sal Franks with the Rhine Franks. Clovis converted to Christianity with 3,000 followers after the victory against the Alamanni in the Battle of Zülpich (496) as a result of a vow .

The most important Sal-Franconian kings in the time of the genesis of the Franks up to the accession of Clovis I:

- Chlodio (Chlojo) (around 430/440)

- The first historically verifiable King of the Salian Franks; he ruled in Dispargum (today's Duisburg or a place of the same name ( Duisburg (Belgium) ) in today's Belgium).

- Merowech (around 455/460)

- Namesake of the Merovingian family; his residence was Tournai in what is now the province of Hainaut . In the legend, Chlodio's wife gave birth to their son Merowech after bathing with a sea monster. This event should indicate the mythical origin of the Merovingian family.

- Ragnachar of Cambrai (486/508)

- Ragnachar was one of several part kings (himself possibly descendant of Chlodius) who were eliminated by Clovis.

- Childerich I. (457 / 63-481 / 82)

- Childerich acted in the final stages of Roman Gaul as administrator (administrator) of the Roman province of Belgica Secunda, where he was also a military commander; at the same time he was King of the Salians. At times he was supposedly deposed because of his "way of life" by the Franks, who are said to have temporarily chosen the Roman army master Aegidius as their leader. After eight years Childerich returned from his exile with the Thuringians and was reinstated as king. To what extent this legendary story is true is very controversial in research.

- Clovis I , son of Childerich (481 / 82–511)

- The Merovingian is described in our main source (the histories of Gregory of Tours ) as a capable, but also cunning and brutal ruler; the extent to which the individual descriptions are correct is, however, controversial. In any case, he gradually eliminated his adversaries, and had Syagrius († 486/487) executed in Gaul after his victory over this last Roman ruler. At last he eliminated the king of the Ripuarier Sigibert of Cologne by a plot and thus sat at the head of all Franks. Around 497 (or only at the end of his reign) he was baptized a Catholic and thus avoided religious-political problems in his empire between the Germanic rulers and the Romansh majority population.

Rhine Franconia

The term Francia Rhinensis has been handed down since the 5th century. From around the 6th century onwards, the tribes that settled on the Middle Rhine and upwards were also referred to as Ripuarians , "bank residents". Along with the Salians, they were the second mainstay of the Franconian expansion - they later became the branch of the Moselle Franconia . The Rhine Franconia spread in the course of the Franconian conquest of Cologne via Mainz to today's Hesse and via Worms to Speyer . The branch of the Moselle Franconia settled in the Moselle valley and in the neighboring areas up to Trier and what is now Luxembourg .

The Rhine Franconians had their own petty kings ; their most important was Sigibert von Köln , also known as "the lame". In alliance with the Salier king Clovis I, he had defeated the Alamanni in the battle of Zülpich in 496 . Nevertheless, he fell victim to a plot by his former comrade in arms, who then also took power with the Rhine Franconians and united the two great Franconian people.

The following are mentioned in written sources from the tribal leaders and kings of the Rhine Franks in the time of the genesis of the Franks to the plot against King Sigibert of Cologne:

- Gennobaudes I (287/289)

- Frankish tribal leader who had to submit to the Romans.

- Ascaricus and Merogaisus (about 306)

- were Frankish tribal leaders who invaded Roman territory in 306, but were defeated by Emperor Constantine . They were accused of wild animals in the Trier arena.

- Mallobaudes (from 378)

- was initially a military leader in the Roman army before he turned away from the Romans and became the small king of the Franks on the Rhine. It is said that in the year 380 he killed the king of the Alemannic Bukinobants, Makrian, in battle.

- Gennobaudes II (from 388)

- in 388 he undertook an attack on the Roman province of Germania together with the military leaders Marcomer and Sunno . The Franks broke through the Roman Limes and devastated the area around Cologne.

- Theudomer (Richimer's son, 413-428)

- It is not known whether the Frankish King Theudomer , mentioned at the time of the Western Roman Emperor Jovinus , belonged to the Rhine Franks. The historian Gregory of Tours reports that Theudomer, son of Richimer , was executed by the sword along with his mother Asycla.

- Sigismer mentioned in 469 as the "son of a king"

- Because of his name he could be counted among the Rhine Franconians. However, his affiliation to the Rhine Franconian region is not guaranteed.

- Sigibert of Cologne (King 483 to 509)

- Sigibert had defeated the Alemanni in alliance with the Salfränkischen Merovingian Clovis I in the year 496/497 in the battle of Zülpich - whereupon Clovis accepted the Christian religion. Sigibert suffered a knee injury in the fight, as a result of which he was nicknamed "the lame". He was murdered by his son at the instigation of Clovis.

- Chloderich the parricide (short term 509)

- The Salfränkischen ruler Clovis I had incited Chloderich to murder his father. After the murder, Clovis also had the "patricide" killed and was proclaimed king by the Rhine Franks.

With Sigibert von Köln and his son, the independent royal house of the Rhine Franconia ended.

Franconian society

The Merovingian Clovis I was the first Franconian ruler to unite all parts of the Franconian region - that of the Sal and the Rhine Franks - in one hand. Former non-Franconian areas were also incorporated into the empire, so that the Franconian Empire (Regnum Francorum) and the Franconian country (Francia) have no longer been identical.

Within the empire, the Franks lived as a people with linguistic and cultural traditions that went back to the time of the (proto) Franconian tribes and whose customs were based on old Germanic-Franconian law despite the advancing Christianization . Clovis I had the Lex Salica written down between 507 and 511 , the legislation of the Salian Franks; the oriented Lex Ripuaria appeared in the 7th century in the Rhine-Franconian area during the reign of King Dagobert I - the last Merovingian who, according to traditional research, still ruled independently. After him, the Hausmeier gradually took over power in the Franconian Empire, although a more precise assessment is made difficult by the tendentious Carolingian (and anti-Merovingian) historiography. While the law of the Frankish people was primarily laid down in the Ripuarian legislation, the Salian legislation also contained extensive legal texts that affected the non-Franconian, especially the Gallo-Roman population. Regulations for the clergy (priests, monasteries, bishops) were also part of the Lex Salica.

Royal law and popular law complemented each other, also in the judiciary. In addition to the Thing , which was held at regular intervals every 40 to 42 days, there were “required” court meetings , the attendance of which was compulsory for those invited.

King and Retinue

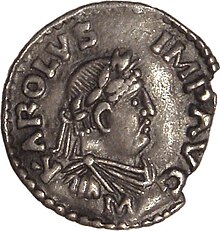

- At the head of the people stood the king (Rex Francorum). His symbols of power were the spear, browband and signet ring . The people paid homage to their king through the so-called "oath of subjects".

- The nobility consisted of the dukes (dux) and counts (comes).

- The military service consisted of the " Leudes ".

Only the male line was entitled to inheritance, after the sons the brothers; these with priority if the sons were considered "not capable of governing".

It is controversial whether the origin and nature of the Franconian nobility are based more on traditional Franconian or late antique tradition - and whether equating the noble titles (comes = "count"; dux = "duke") is justified for the time. In Gregory of Tours is commander and tribal leader Germanic peoples. He speaks of the "Duces of the Franks before these kings had". There was also a “amalgamation” of Frankish-Germanic and Roman-Gallo-Roman factors in the administration. The mounted royal retinue (Antrustionen) originally consisted only of Franks. The queen was also entitled to her own protection force.

In the administration (especially in the spiritual area), members of the Gallo-Roman elites who had the appropriate knowledge still dominated in the early Merovingian period . Gregor von Tours, for example, was one of the distinguished Gallo-Romans who never completely gave up their Roman-influenced cultural identity and who also played an important mediating role in this regard.

An important attribute of the Germanic king was the treasure, which was his personal property; without this it would hardly have been possible to reward the services of the followers, to lead a lavish lifestyle or to release hostages. Loot of war, inheritance, tribute payments , gifts, and looting increased the treasure. Taxes and duties were levied to deal with government spending.

The king and his entourage were constantly on the move to be present in many places. The empire was ruled from the saddle. The armies carried a train with them and were equipped with carts and wagons, which were put together to rest (or to protect against attacks) in a wagon castle. The aim of the war was - besides honor and reputation - above all the booty. For the ruler it consisted of land and an expansion of power, for the Frankish warrior it consisted of captured property. It was not uncommon for the prey to begin while passing through one's own territory, as the entourage had to be fed. Bringing in prisoners was also worthwhile, as they were cheap labor or - if they were of high birth - promised lucrative ransom money.

The Frankish warrior was armed with a lance and a throwing spear. The characteristic Franconian national weapon was the " Franciska ", the throwing ax. It can often be found in the inventory of Franconian graves up to the 8th century. Handling them was difficult and required a certain degree of accuracy. It is known of Clovis that he (at least according to Gregor von Tours) split the skull of a warrior with an ax in front of everyone who wanted to dispute his booty - the "Vase de Soissons". Another powerful weapon was the "Spatha", which was used by all Germans, but was also widespread in the late Roman army. It is a double-edged long sword, often damascene . Some warriors used a "slash sword", the "scramasax" or daggers (saxa) as stabbing weapons.

As a protective weapon there was the shield (which also played a role in the elevation of the king's shield ). Armor and iron helmets were only worn by distinguished warriors. The Lex Ripuaria reports on Brünne , helmet and greaves (begnberga). In 1962 the pristine grave of a local Franconian prince named Arpvar was uncovered in the area in front of the former Roman fort Gelduba in what is now Krefeld-Gellep , and it was richly furnished with personal and military gifts, among others. a. with a golden Byzantine spangenhelm and a complete set of weapons.

Free and unfree

The population was divided into classes, including:

- Free ( ahd. Frīhals , lat. Liberi , ingenui ) (the individual Frankish man, conscript)

- Freedmen ( mnl. Vrilaet , lat. (Col) liberti )

- Semi-free (mnl. Laet , lat. Leti , lidi )

- Serfs , unfree ( ahd.teo , dio , lat.servi )

- Roman (Free Roman = Romanus Possessor, member of the middle class)

- Roman serfs (colone)

From the term Franci for the (individual) Free (Franconian), the adjective “franc” for “free” emerged over the years in Romansh-speaking countries - from which the German equivalent was borrowed around the 15th century. In contrast to, for example, the relationship between the ( Arian-Christian ) Goths and their Roman ( Catholic-Christian ) roommates, there was no legally prescribed marriage ban between Franks and other ethnic groups among the Franks. An integral part of the Franconian legal system was the wergeld (man money, from Old Franconian who for "man"), an expiation money that was created to curb the blood vengeance and the resulting permanent feuds between the clans. For members of the Franconian people different sentences than for "non-Franconians" (Romans and Gallo-Romans) applied. For the killing of a franc, double the Wergeld was due as for a Roman living in a comparable position.

The wergeld was for example:

- 200 solidi for one free franc (franci)

- 100 solidi for one half-free franc (lidi)

- 100 solidi for a free Roman (romanus possessor)

- 600 solidi for the mounted Frankish followers ( Franco - Latin dructis ) of the king (Antrustiones)

- 300 solidi for followers from the Gallo-Roman population (convivae)

- 600 solidi for a priest

- 900 solidi for a bishop

Since "cash" (coins) were usually rare (among the general population), wergeld - if it was due - was often converted into natural products, cattle or land.

The Frankish man was the typical “free one”; a Roman always dependent in some way. However, as a result of mixed settlement, religious equality and connubium, he had the opportunity to join the "Frankism". This was expressed in the preference for Frankish names on the part of the Gallo-Romans as well. It was also not uncommon for the Romans to take on important administrative posts, which also applied to spiritual offices and the priesthood.

Cult and Church

Before converting to Christianity, the Franks had cultivated their tribal cults. In addition to general Germanic traditions, the - predominantly Istaevonian - Franks were worshiped of the Germanic progenitor "Mannus" and his son "Istio".

In Germania Tacitus reports on the Germanic god Tuisto and his son Mannus, founder of the Germanic family. Accordingly, Mannus had three sons, after whom the tribes living by the sea were named Ingaevonen , the middle (inland) Herminonen and the Istaevonen living on the Rhine. For the Merovingian rulers there was also a mythological saga of origin about a sea monster as the founder of the Merovingian family.

For the early Franks, nature and the forces working in it were of great importance. There were sacred places and wooden temples in forests and meadows and carved figures that were modeled on sacred animals. The Franks knew animal sacrifices (horse sacrifices) and human sacrifices. It is said that even after their Christianization, Frankish warriors sacrificed the corpses of prisoners to the river spirit before crossing a river.

Although the Merovingian Clovis I was baptized around the year 497 (the exact date is still disputed in research today), many Franks remained stuck with their old beliefs for a long time.

Cremation was originally common among the Teutons. From the 4th century onwards, the Franks switched to body burial, depending on the status of the deceased with rich grave goods. The grave of the Merovingian king Childerich I, rediscovered in Tournai in May 1653, was unusually richly furnished. In the grave there was a purple, gold-woven cloak set with gold cicadas. The king's golden signet ring and a bangle made of solid gold, an iron throwing ax, a lance and a gold handle spatha with quillons and scabbard were found. The skeleton of the Frankish king measured 179 cm. In the grave itself there was a sacrificed horse's head, and other horses had been buried in the ground in the immediate vicinity. Up until the 8th century, grave goods were found in Franconian graves - atypical for Christian graves - which indicate “ pagan ” burial rites - for example in the grave fields of Krefeld-Gellep ( Gelduba ).

According to Gregory of Tours , at the time of Theuderic I (from 511 to 533 King of the Rhine Franks in Australia ) there were pagan temples in Cologne, where the Franks had sacrificed and enjoyed food and drink. The Franconian temples, which were scattered around the country, were burned in the following years. T. Christian chapels or churches built.

Rules were laid down in the Lex Ripuaria to ward off pagan customs . So was z. B. the hazel magic prohibited. The fruits of the hazel were considered an elixir of love. The hazel bush was ascribed powers against lightning strikes and earth rays, hazel rods were used as dowsing rods and hazel branches were used to ward off witches . Despite the ban, the hazel customs persisted into the high Middle Ages.

Frankish Christianity emerged with the baptism of Clovis, which was of epoch-making importance. With the conversion, the empire was considered Christian ( Catholic ). Since Catholicism had prevailed among the Gauls in the preceding centuries, there were no conflicts between Franks and Gallo-Romans in this regard. The organization of the Gaulish Church - dependent on Rome - had survived the crumbling of the Roman Empire. Through the Christianization of the Frankish king and his followers, the church experienced a consolidation. The ecclesiastical administrative units (dioceses) were consolidated and formed a bastion in the Franconian Empire. No resistance against the Frankish rulers was to be expected from the church; on the contrary, it saw itself fully integrated into the Frankish state to which it submitted. This in turn helped the Merovingians to enforce their claims to power against other Gallo-Roman areas without resistance from the church and thus to enlarge their empire. Inside, the church occasionally formed a refuge for the defeated of the internal Merovingian power struggles. Opponents of the king and unpleasant counts were either killed or given the choice of being sheared and going to a monastery.

House and yard

The farms of the early Franks were scattered across the country; however, there were village settlement structures and hamlets, especially near rivers or in forest clearings. The most common building material used was wood. In the Franconian expansion areas to the left of the Rhine and in Toxandria, the Franks linked up with the abandoned settlement areas of the Romans.

Since livestock farming played a major role, people preferred to settle near bodies of water because of the water supply.

A group of houses comprised residential buildings, annex buildings, stables and storage rooms, all of which were fenced off. Overcoming the fence (not just entering the house) was already a violation of the law. Two different types can be distinguished in the construction of residential buildings:

- ground-level post structures

- recessed pit houses

The length of the single-storey buildings varied between 10 and 40 meters, the width was usually 4 to 6 meters. The beam construction of the buildings required competent and solid carpentry. The buildings were mostly single-nave, with a central section open to the roof with a hearth space. Often times the houses were residential / stable houses in which the cattle were housed in a separate area. The so-called in today Oberfränkische Ernhaus was such a eaves serviced byre-dwelling with entrance on the long side, which in the Ern led (the central hall with cooker).

The pit house was laid out more simply. A rectangular or oval pit was dug, three to four meters in diameter. With a roof that reached to the ground, it may have looked like a tent-like hut.

Several such courtyards formed the hamlet or the village. Adjacent to this were the gardens, meadows and fields, and depending on the area also vineyards. The names of the villages often ended in "-weiler", "-rode" and especially on forms of "-heim" often transformed to "-um" (examples: Gerresheim, Blankenheim, Latum = Latenheim, Ossum = Ochsenheim).

Agriculture was the most important livelihood for the Franks. Even if (or because) the farmer was the rule, there was no special word for it. Every Franconian living in the country was a farmer. The term "Ackerer" or "Ackermann" appears in translations. The word farmer - in the sense of "cultivating the land" - did not emerge until the early modern period.

Because of the transience of the materials, archeology found hardly any equipment made of wood or bone, although there were a few iron plowshares, sickles, scythes, spade and saw blades and winegrower's knives. The potter's wheel was common from the 6th century, before pottery was made “by hand”. Cattle breeding was of particular importance. Cattle and goats were short and lightweight. The horses, too, were stout, with a height at the withers of 140 cm, and were used, in addition to oxen, for field and forest work. Pigs in particular were kept for meat, but also poultry (chickens, geese).

Today, pig herds of around 25 to 50 animals are assumed, with cattle the herds were smaller. Theft of cattle was punished severely. The Lex Salica provided graduated penalties for cattle theft. In popular law, the swineherd is emphasized above the cattle, sheep and goatherds, for example by a higher wergeld (fine for manslaughter).

Pond fowl and chickens were also kept for the eggs. Beekeeping was an important branch of agriculture, since honey was in principle the only means of sweetening food and drinks (enclosed beehives were part of the domestic peace area). The horse was a work animal and a riding animal; a herd of horses consisted of the stallion with up to 12 mares and foals.

Fishing with a net and trap also had a certain importance. The forerunners of today's wheat and barley varieties were grown on grain, and to a lesser extent rye and oats. Flax was used for linen production and oil production. The Franks knew wine-growing from the Romans. In the Franconian region on the right bank of the Rhine, the aforementioned structures persisted into the Carolingian era. In the area on the left bank of the Rhine in what is now Germany, many Roman settlements and forts were plundered and destroyed by attacks by the Franks and were never repopulated. Only the big cities such as Cologne, Trier, Koblenz or Mainz were continuously inhabited from Roman times through the Franconian times to modern times. Fortresses like Gelduba were razed to the ground or fell into disrepair. This also applies to the formerly flourishing Roman city of Xanten ( Colonia Ulpia Traiana ). In the new town built a few hundred meters to the south, there are plenty of bricks from the old Roman settlement used as building material.

The situation was different in the (Gallo-Roman) cities - as long as they were not abandoned by the inhabitants fleeing from the Franks. In what is now the French part of the Franconian Empire, the Franks found stone-built cities and houses surrounded by walls. Quite a few Francs, especially those of a higher class, settled there or married into urban families.

A distinction between the settlement structures, construction methods, forms of burial or the customs of Sali, Rhine and Moselle Franconia is - for the early Franconian period - neither proven by written sources nor by archaeological findings.

Clothing and equipment

From grave finds, illustrations and descriptions it can be deduced how the Franks were dressed. Linen and sheep's wool must be verified as the main material for clothing . The men wore long, tight-fitting trousers-like trousers and calf bands . In addition, an almost knee-length outer garment with long, wide sleeves. A throw served as a coat.

Leather belts up to 8 cm wide and metal buckles and metal brooches to hold the throws together were worn around the hips. The women wore a tunic- like robe, cut from a rectangular piece of fabric and sewn to the side. It was thrown over the shoulder and held by two fibula clasps . The Franks wore simple waistbands on their feet, pulled together with straps, the ends of which crossed around their calves. Waistband shoes and calf bands were typically Franconian and unusual among the Gallo-Romans.

The Gallo-Roman Sidonius Apollinaris reports on the clothes of noble Franks and their war followers :

- “As for the princes and their followers, they were a terrifying sight even in peacetime. Her feet were laced up to the ankles in shoes made of fur, her calves uncovered, and over them brightly colored, tight-fitting clothing. Their green coats wore dark red braids; their swords hung from their shoulders in weir hangings and pressed against the waist, wrapped in a leather belt adorned with nails. Her equipment adorned and protected her at once. They carried barbed lances and throwing axes were in their right hands; their left side was protected with shields, the sheen of which - silver-white on the edges - golden-yellow on the shield bosses - betrayed both the wealth and the passion of their wearers. "

Elsewhere Sidonius continues:

- "... Their eyes are as clear as water, their faces are clean-shaven, instead of beards they wear thin mustaches that they groom with a comb."

Sidonius later explains, slightly glorifying:

- “... They enjoy throwing their axes through the wide space and knowing beforehand where they will fall. Swinging their shields and throwing spears that overtake them in leaps. Undefeated, they are steadfast and their courage almost outlasts their lives. "

The Franconian women wore their hair held together with hairpins, often in a knot or braided wreath hairstyle.

From the vita of the Frankish emperor Charlemagne , written by the Franconian historian Einhard , we know how the emperor dressed himself:

- “... according to Franconian custom he hunted and rode diligently. He loved the hot springs (of Aachen) and swam a lot and well. Often more than a hundred people bathed with him. He dressed in the costume of the Franks: a linen shirt on his body, linen trousers covered over his thighs; over it a tunic, which was edged with silk, the lower legs were wrapped with ribbons. His calves were also laced and he wore boots on his feet. In winter he protected his shoulder and chest with a doublet made of otter skin or marten skin . Over it a blue cloak. He always wore a sword with a hilt of gold and silver. At receptions he wore a sword studded with precious stones. He never wore foreign clothes. On high feast days he wore gold-woven clothes and shoes and a diadem made of gold and precious stones. On ordinary days he was dressed like any other Franconian. "

- Finds from the Frankish period

Golden Spangenhelm from the princely grave of Krefeld-Gellep

(6th / 7th century)Parts of the sword hilt of the Salfränkischen king Childerich I

(5th century)

Franconian language

There are only a few written documents on everyday language from the founding time of the Frankenbund. In late ancient Latin or Greek scripts, there are occasional Franconian names , mostly in connection with names of areas, tribes or rulers.

Franconian, like other Germanic rulers' names, often contain syllables like “Theud” (Theuderich) “Mero” (Merowech), “Chlod” (Chlodwig, Chloderich), “Sig” (Sigibert, Sigismund), which can be easily identified as Germanic . The frequently encountered sequence of letters at the beginning of a name like "Ch" in Clovis was probably not pronounced as a hard "K" but as a fleeting throat-h and then sounded more like "hLudwig" instead of Clovis , after "hLothar" instead of Chlothar .

The earliest Old Franconian (Salfränkische) sentence that has survived comes from the Lex Salica of the 6th century:

- Maltho thi afrio lito

- Literally: (I) report to you free late

- Basically: (I) tell you I set you free, semi-free (lito)

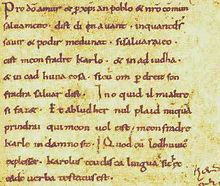

From the 9th century (300 years later) there is a document from the period of the separation of the western Franconian people from the rest of the people: the Strasbourg oaths . They sealed the alliance between two grandchildren of Charlemagne against their brother, the third grandson. Because the Franconian entourage did not ( or no longer) understood the language of the other side, the oaths were spoken in two languages - in a forerunner form of Old French (the language of Charles the Bald ) and Old Franconian (the language of Ludwig the German ). The text in the old Franconian language read:

- In godes minna ind in thes christanes folches ind our bedhero salary fon thesemo dage frammordes so fram so mir got geuuizci indi mahd furgibit so haldih thesan minan bruodher soso man with rehtu sinan bruodher scali in thiu thaz he mig no sama duo indi thing ne gango the minan uillon imo ce scadhen uuerdhen.

- For the love of God and the Christian people and our salvation, from this day on, as far as God gives me knowledge and ability, I will support my brother Karl, both in helping and in every other matter, just as one supports his brother should that he do the same to me, and I will never make an agreement with Lothar that willingly harm my brother Karl.

The following text comes from a document from the 11th century, written in the Dutch Abbey of Egmond and called Leidener Willeram :

- Section 22 (Vox Christi ad ecclesiam):

- Sino, scona bistu, friundina min - sino, scona bistu; thin ougan sint duvan ougan.

- Scona bistu to guoden werkan, scona bistu to reynan gethankon. Thin eynualdigheyd skinet an allan thinan werkon, wanda thu ueychenes ande gelichnis niet neruochest.

- Section 22 (Christ speaks to the Church):

- You are beautiful, my friend, you are beautiful; your eyes are dove eyes.

- You are beautiful in good deeds, you are beautiful in pure thoughts. Your purity / sincerity (eynualdigheyd) becomes clear (skinet) in all your deeds, because (wanda) you do not strive (niet neruochest) for deceit and hypocrisy (ueychenes ande gelichenisses).

A "famous" sentence is dated to the 12th century and is considered the most important Old Dutch (Old Franconian) written document - Hebban olla vogala - an almost poetic rhyme:

- Hebban olla vogala nestas hagunnan hinase hic enda thu uuat unbidan uue nu

- Have all the birds started nests except me and you, what are we waiting for?

Charlemagne can also serve as a spokesman for Franconian; In his vita , Einhard reports on the emperor that although he could speak Latin and hardly speak Greek, he could understand it - but he prefers to use his Frankish mother tongue. Abstract:

- ... he also had the ancient pagan songs written down, the deeds and wars of the old kings. He also started with a grammar in his mother tongue. He also gave the Latin names of the months uniform Franconian names. He named January Uuintarmanoth (winter month), February Hornung, March Lenzinmanoth (springtime), April Ostarmanoth (Easter month), May Uuinnemanoth (pasture month), June Brachmanoth (fallow month), July Heuuimanoth (hay month), August Aranmanoth (harvest month), September Uuitumanoth (forest or wood month), October Uuindumanoth (wine month), November Herbistmanoth (autumn month), December Heilagmanoth (holy month). He also gave Franconian names to the winds ...

Only the written documents from the 14th to the 16th century seem more understandable for today's readers. Here is an example from the Rhine Maasland period of the Lower Franconian:

From an alliance letter dated 1364 from Count von Berg (Düsseldorf) and Kleve to the Dukes of Brabant, Jülich and the city of Aachen (available in the public state archive of Düsseldorf):

- At dyn gheswaren des verbunts of the hertoghen van Brabant, van Guilighe ind the stat van Aken ... but we can say that we are in touch with af vernemen, of uytgheghaen, that soude wi like to na onsen so special iin doen, dat ghiit with gůede nemen soudt. Oeck soe siin wi van daer baven vast aenghetast end ghebrant, daer wi but the waerlich nyet monkey enweten, van wylken steden of sloeten ons dat gheschiet sii. Got bewaer u guede vrynde altoys. Contr. tot Cleve op den Goedesdach na sent Lucien dagh.

A certain closeness of this text to today's Dutch and to the dialects spoken on the Lower Rhine from Kleve to Düsseldorf is unmistakable. From the examples given, it is easy to deduce how far the dialects known today as "Lower Franconian", "Ripuarian", "Rhine" or "Moselle Franconian" are from the language of the early Franks or Charlemagne.

The influence of the Franconian language on Gallo-Roman and Old French was very strong and ultimately led to the special position of French within the Romance languages, as it has developed most strongly from Latin. In addition to phonological and grammatical influences, several hundred loanwords have been preserved, especially terms from the military, seafaring and abstract terms. Many Franconian words have also been preserved in the basic French vocabulary: too much = trop, hardly = guère, screeching = crier, dancing = danser, forest / forest = forêt, win = gagner and also installer which is related to the German hiring. The Germanic influence is also noticeable in the colors: brown = brun , blue = bleu , white = blanc , gray = gris .

From the Merovingians to the Carolingians - the separation of the people

The process of concentration in the political sphere, which finally led to the unification of the Sal Franks with the Rhine Franks under Clovis I, had promoted the common popular consciousness of all Franks living within the borders of the empire. This was expressed in the written people's rights, the Lex Salica and the Lex Ripuaria , in which the members of the Frankish people are differentiated from other tribes and ethnic groups. The development of sub-tribes over the large tribe to popular education was completed at the latest with the unification of the Sal and Rhine Francs in the empire. After that, however, a process began that was to lead to the linguistic separation of the people in the 9th century.

The religious rapprochement with the Gallo-Roman population, which was also Catholic, and the legal tolerance of marriages between the ethnic groups, brought about by Clovis I's conversion to (Catholic) Christianity, laid the foundation for a cultural, but also (for the majority of the Salfranken) linguistic merger with the subject Population laid. The Franks, who settled in today's German-Dutch language area, assimilated the subject population linguistically and culturally.

In the period that followed, there were repeated internal power struggles among the Merovingians and the division of the empire several times. They lost power in the course of the 7th century and came under the influence of the increasingly influential Hausmeier , who gradually took over government. The Merovingian Dagobert I (629–639), who first ruled Austrasia and then ruled the entire empire, gained importance again . After that, the Pippinids or the early Carolingians were in fact the rulers of the empire, although the Merovingians continued to provide kings until the middle of the 8th century. The most important early Carolingian was Karl Martell (an illegitimate son of Pippin the Middle ), who subjected the Alemanni and Thuringians to the rule of the Hausmeier and made Bavaria dependent on the Franconian Empire. In 732 his army defeated the Arabs and prevented them from advancing further into Central Europe.

The last Merovingian shadow king Childerich III was among the sons of Karl Martell . discontinued; Karl Martell's son Karlmann went to a monastery, whose brother Pippin was elected King of the Franks in 751. After Pippin's death, the empire was divided among his sons Karl and Karlmann - the latter died before disputes broke out and thus Charlemagne was able to take over power in the Frankish Empire . Under Charlemagne, who was crowned emperor in December 800 and thus renewed the western empire, the Frankish empire reached its greatest extent. After the brutally waged Saxon Wars, Karl incorporated the Saxons into his empire and extended the borders to the Slavic regions and to northern Spain. The Franconian Empire had long ceased to be a “land of the Franks”, but rather a multi-ethnic empire and comprised the core area of western Christianity.

The process of separation of the Franconian people finally became clear when the alliance between the grandchildren of Charlemagne, the West Franconian King Charles the Bald and the East Franconian King Ludwig the German against their brother Lothar was sealed . The Strasbourg oaths spoken on February 14, 842, were taken in two different vernacular languages because the respective followers did not (or no longer) understand the language of the other side. The division was finally sealed in the Treaty of Verdun in 843.

The sub-tribes united for the first time under Clovis I were henceforth linguistically separated and in the late Carolingian period two separate empires emerged with West and East Franconia. The concept of the "people of the Franks" receded more and more. From then on, the new Gallo-Roman ( old French ) language, which was created by amalgamation, dominated in the west, while the Franconian dialects remained in the east . A large part of the Salfranken merged in the people of the French and Walloons . The Salfranken and the Moselle and Rhine Francs that remained in today's Netherlands and the Flanders region and on the Lower Rhine were later absorbed by the Germans, Dutch, Lorraine, Luxembourgers and Flemings.

Chronology to Clovis I.

(From the first mention to the unification of the sub-peoples under Clovis I; excerpt):

- 257/259 raids by Germanic groups against the Romans take place, referred to as Franks in later sources

- 275/76 (proto) Franconian tribes repeatedly advance into Roman areas from the right bank of the Rhine

- In 288/89 the military leader Gennobaudes submitted to the Roman emperor Maximian , who confirmed Gennobaudes as a minor king

- 291 first recorded mention of the name of the "Franks" - but the names of the tribes remain in use

- 294 francs penetrate into the "Batavia", be there by Constantius Chlorus as laeti settled

- 306/307 Frankish groups break into Gaul (see Ascaricus ). There follow Roman punitive actions against the Brukterer; the Franconian leaders are thrown into the hands of the predators in Trier.

- 313 to 341 incursions by Franconia into the area on the left bank of the Rhine. Trier and Cologne are repeatedly attacked

- 352 Collapse of the Roman Rhine line, Rhine Franconia settle on the left bank of the Rhine

- 356 to 387 battles between Romans and Franks with varying successes

- In 388, under the Roman emperors Valentinian I and Gratian , Frankish military leaders attained top military positions ( Merobaudes , Richomer , Bauto , Arbogast and others). in the fight against the Alemanni

- 388 to 400 constant unrest on the Rhine, a. a. under the Frankish leaders Marcomer , Gennobaudes and Sunno . Relocation of the Roman-Gallic prefecture from Trier to Arles for security reasons

- 413 to 435 francs attack Trier repeatedly; In 435 the city fell into the hands of the Franks

- 446 Chlodio , leader of the Salfranken, crosses the coal forest and conquers the country as far as the Somme

- 451 in the battle of the Catalaunian fields , Franks fight on the side of the Romans as on the side of Attila, king of the Huns .

- 455 to 460 Merowech , namesake for the Merovingian family, ruled the Salfranken.

- around 459 Cologne finally falls into the hands of the Franks and becomes the residence of the Rhine-Franconian kings.

- 463 and following years: the Merovingian Childerich I , king of the Salfranken, penetrates as far as Paris; repeated fighting in the Loire region (see also Adovacrius ).

- 483 in Cologne ruled the Rhine Franconian small king Sigibert

- 486/87 Clovis I (Childeric's son) defeats the Roman Syagrius and thus removes the last Roman bastion in Gaul.

- In 496/97 in the Battle of Zülpich the Rhine-Franconian King Sigibert and the Sal- Franconian Merovingian Clovis I fight together against the Alemanni. After the victory, Clovis converts to Christianity.

- 509 The King Clovis I of Sal Franconia instigates Sigibert's son Chloderich to assassinate his father. Then Clovis eliminates Chloderich too . Clovis I is made king by the Rhine Franks; Association of Rhine Francs and Sal Francs .

- 511: Death of Clovis and division of the empire

1: North Lower Franconian ( Brabantisch , Kleverländisch , Ostbergisch)

2: South Lower Franconian ( Limburgish )

3: Ripuarian

4: West Moselle Franconian

5: East Moselle Franconian

6: Rhine Franconian

Name of the franc

Historically, the terms “Salier” and “Salfranken” on the one hand and the terms “Rheinfranken” and “Ripuarier” on the other hand have been equated. The early "Salians" are, however, to be distinguished from the sex of the dukes of Lorraine and Upper Franconia of the 11th / 12th. Century, who also called themselves "Salier".

The equation of “Rhine Franconians” and “Ripuariern” is only partly justified today. "Rheinfranken" were all Franks that spread from the Middle Rhine with a focus on Cologne to the south, southeast and southwest, with the subgroup of the "Moselfranken". From the 6th century on, the Rhine Franconians were also called "Ripuarier" (river bank inhabitants). From a dialect point of view, “ Ripuarian ” is only used today to refer to dialects across the Rhine in south-west Bergisch via Cologne to Aachen; This is to be distinguished from Moselle Franconian on the Moselle and Rhine Franconian in the Rhine-Main area as well as the Lower Franconian dialects on the (German) Lower Rhine, in the Netherlands and Belgium, which are derived from Sal Franconian , according to the Rhenish subjects published by the Rhineland Regional Council (LVR) .

Numerous dialects of the German and Dutch-speaking areas in today's Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands - but also Afrikaans and other emigrant dialects - were traditionally referred to as Franconian .

The modern region of Franconia historically formed the eastern settlement area of the tribe. Its inhabitants are still referred to as Franks today. Archaeologically, the area was heavily franked in the 6th and 7th centuries. Franconian graves from this time can be found in northern Bavaria . The settlement movement of the Franks from west to east is called Franconian land acquisition . Whether this should be interpreted as a violent campaign of conquest or as a step-by-step process is discussed in science.

swell

The Franks are mentioned in various late antique sources, but not dealt with in detail. In addition to scattered mentions in the non-narrative sources, Aurelius Victor , Ammianus Marcellinus and Priskos , among others , are important . The most important and detailed source on the history of the Franks (especially since the late 4th century) is the historical work of Gregory of Tours until the late 6th century , which is known as Decem libri historiarum ("Ten books of stories") or Historiae (" Histories "), often incorrectly referred to as" Franconian history ". The less reliable Fredegar Chronicle (7th century) and the Liber Historiae Francorum are important for the late Merovingian period .

The most important Carolingian source is the Annales regni Francorum (from 741 to 829), which is above all a kind of account of Charlemagne's deeds; this is followed by various sequels for West and East Franconia ( Annalen von St. Bertin , Annalen von Fulda ). There are also other works, including Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni .

In addition to the narrative historiographical sources, various other sources are available, including legal texts, letters, church sources, edicts and various vites.

- Reinhold Kaiser , Sebastian Scholz : Sources on the history of the Franks and the Merovingians. From the 3rd century to 751st Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 3-17-022008-X .

- Alexander Callander Murray (Ed.): From Roman to Merovingian Gaul: A Reader. Broadview Press, Peterborough (Ontario) 2000.

- Gregory of Tours: Ten Books of Stories. 2 volumes. Based on the translation by Wilhelm Giesebrecht , revised by Rudolf Buchner. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1955/1956 (and reprints).

- Reinhold Rau (Hrsg.): Sources for the Carolingian Empire history. 3 volumes. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1955–1960 (several NDe).

literature

See also the information in the articles Merovingians and Carolingians .

- A. Wieczorek, P. Périn, K. von Welck, W. Menghin (eds.): The Franks. Pioneer of Europe. 5th to 8th centuries. 2 volumes. von Zabern, Mainz 1996 (1997), ISBN 978-3-8053-1813-6 .

- Eugen Ewig : The Merovingians and the Franconian Empire . 5th updated edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-17-019473-9 .

- Dieter Geuenich (ed.): The Franks and the Alemanni up to the " Battle of Zülpich " (496/497). Real Lexicon of Germanic Antiquity . Supplementary volume 19. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1998, ISBN 3-11-015826-4 .

- Bernhard Jussen : The Franks. History, society, culture. C. H. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66181-5 .

- Mischa Meier , Steffen Patzold (Ed.): Chlodwigs Welt. Organization of rule around 500. Steiner, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-515-10853-9 .

- Ulrich Nonn : The Franks. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010.

- Rudolf Schieffer : The Carolingians . 4th edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2006.

- Sebastian Scholz : The Merovingians. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3-17-022507-7 .

- Erich Zöllner : History of the Franks up to the middle of the 6th century. Revised on the basis of the work of Ludwig Schmidt with the assistance of Joachim Werner. Beck, Munich 1970.

- Hermann Ament, Hans Hubert Anton, Heinrich Beck, Arend Quak, Frank Rexroth, Knut Schäferdiek, Heiko Steuer, Dieter Strauch, Norbert Voorwind: Franconia . In: Heinrich Beck, Herbert Jankuhn, Heiko Steuer, Dieter Timpe, Reinhard Wenskus (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Vol. 9, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1995, ISBN 3-11-014642-8 , pp. 373-461.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Aurelius Victor, Caesares , 33.3.

- ↑ See the background to Henning Börm : Westrom . Stuttgart 2013.

- ↑ Jörg Jarnut: Germanic. Plea for the abolition of an obsolete central concept of early medieval research . In: Walter Pohl (Ed.): The search for the origins. On the importance of the early Middle Ages. Vienna 2004, pp. 107–111.

- ↑ Ludwig Rübekeil: European names of nations . In: Ernst Eichler, Gerold Hilty , Heinrich Löffler, Hugo Steger, Ladislav Zgusta (eds.): Name research. An international handbook on onomastics, second half volume, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-020343-1 , pp. 1330–1343, here: 1330–1332; Ludwig Rübekeil: tribal and peoples names . In: Andrea Brandler (Ed.): Types of names and their research - A textbook for the study of onomastics. Festschrift for Karl-Heinz Hengst , Baar, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-935536-34-8 , pp. 744–771, here: pp. 757–761 (on the basic methodology etc.).

- ↑ See the hints in Lemma cheeky , in: Etymologisches Dictionary des Deutschen. Developed at the Central Institute for Linguistics, Berlin, under the direction of Wolfgang Pfeifer. Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, Munich 1997, p. 371.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 11ff.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 1–3 (Chapter: “Tribal formation”); Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 14. - Cf. already the Lemma frank , in: Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, German dictionary . 16 volumes in 32 sub-volumes. Leipzig 1854–1961.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 35 ff.

- ^ Margot Klee: Limits of the Empire. Life on the Roman Limes. Verlag Konrad Theiss, Stuttgart 2006, pp. 33-40, ISBN 3-8053-3429-X .

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 109.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 2; Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 18

- ↑ General see Eugen Ewig: Die Franken und Rom (3rd – 5th centuries). An attempt at an overview. In: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter. Volume 71, 2007, pp. 1-42.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 32 (map)

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , pp. 19-30.

- ^ Gregory of Tours , Histories II 31.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , pp. 30-31

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 33

- ↑ Friedrich Prinz: Celts, Romans and Germanic peoples. Piper, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-492-24295-0 , p. 128 ff.

- ↑ Heike Grahn-Hoek: Was there a Thuringian empire on the left bank of the Rhine before 531? In: Journal of the Association for Thuringian History. 55, 2001, pp. 15-55.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 146 (timetable).

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 17

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 106 (King's list, excerpt)

- ^ Joseph Milz: History of the City of Duisburg. Mercator, Duisburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-87463-522-6 , p. 20.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 83

- ^ Matthias Becher : Clovis I. The rise of the Merovingians and the end of the ancient world. CH Beck, Munich 2011.

- ↑ Reinhold Kaiser: The Roman Heritage and the Merovingian Empire. 3rd revised and expanded edition. Munich 2004, p. 20.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 91 (map) to p. 94 (map)

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 106 (King's list, excerpt)

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 38, 106

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 111

- ^ Rudolf Sohm: About the origin of the Lex Ribuaria. Hermann Böhlau publishing house, Weimar 1866.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 149.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 120, 122-124.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 125.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 139-145.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 138.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 136, 171.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 153-158.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 155-161.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 155.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 155-162.

- ↑ Feinendegen / Vogt (ed.): Krefeld - the history of the city, volume 1. Renate Pirling - chapter: Das Fürstengrab / page 227 f., Verlag van Ackeren, Krefeld 1998, ISBN 3-9804181-6-2 .

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 115, 117, 119, 132 ff.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 117 ff.

- ^ Rudolf Sohm: About the origin of the Lex Ribuaria. Verlag Hermann Böhlau, Weimar 1866, p. 17.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 115-119.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 119.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 178-179.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 177.

- ↑ Bruno Bleckmann: The Teutons. CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-58476-3 , p. 291.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , pp. 114-116.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 124.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , pp. 110-113.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 177-178.

- ↑ Real Lexicon of Germanic Antiquity . 2nd Edition. Volume 14, p. 35 ff.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. C. H. Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 181-183.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , pp. 34, 117-119.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 121.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 122 ff.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 122 ff.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 125.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 125.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks . Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , pp. 33-36.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 130.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 127 ff.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 130.

- ^ Einhard: Vita Karoli Magni. Cape. 22 f.

- ^ Karl August Eckhardt : Lex salica. Hahn, Hannover 1969, ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica ; Leges; Leges nationum Germanicarum; 4, 2) ISBN 3-7752-5054-9 .

- ↑ Erwin Koller: On the vernacular of the Strasbourg oaths and their tradition. In: Rolf Bergmann, Heinrich Tiefenbach, Lothar Voetz (Ed.): Old High German. Volume 1. Winter, Heidelberg 1987, ISBN 3-533-03878-5 , pp. 828-838, EIDE.

- ↑ A. Quak, JM van der Horst: Inleiding Oudnederlands. Leuven 2002, ISBN 90-5867-207-7 ; Willy Sanders, article Leidener Willeram. in: Autorlexikon 5. 1985, Sp. 680-682.

- ↑ A. Quak, JM van der Horst: Inleiding Oudnederlands. Leuven 2002, ISBN 90-5867-207-7 .

- ^ Translation according to Einhard: Vita Karoli Magni. Reclam, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 978-3-15-001996-2 , p. 55 ff.

- ↑ Irmgard Hantsche: Atlas for the history of the Lower Rhine. Series of publications of the Niederrhein Academy Volume 4, ISBN 3-89355-200-6 , p. 66.

- ^ Stadtarchiv Düsseldorf, archive directory - Dukes of Kleve, Jülich, Berg - Appendix IV.

- ↑ For an introduction to Merovingian history, see Eugen Ewig: The Merovingians and the Franconian Empire. 5th updated edition. Stuttgart 2006.

- ↑ For the development in West and East Franconia see Carlrichard Brühl: Germany - France. The birth of two peoples. 2nd edition Cologne / Vienna 1995.

- ^ Children, Hilgemann: DTV Atlas for World History - From the Beginnings to the French Revolution. Dtv, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-423-03001-1 , pp. 121-123.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 146 ff.

- ^ Nina Kühnle: Konrad II. (1024-1039) - Prelude to a dynasty . In: Historisches Museum der Pfalz Speyer (Hrsg.): The Salier . Power in change. 2011, p. 12 .

- ^ Frank Siegmund: Alemannen und Franken (supplementary volumes to the Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde Volume 23). Walter de Gruyter Verlag, Berlin 2000, p. 355 f.

- ^ Christian Pescheck: The Franconian row grave field of Kleinlangheim, district of Kitzingen / Northern Bavaria . Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1996.

- ↑ See Reinhard Schneider: Das Frankenreich . Walter de Gruyter Verlag, Berlin 2014, pp. 7–8

- ↑ See the two source collections by Kaiser / Scholz and Murray mentioned here, where the source texts are available in translation.