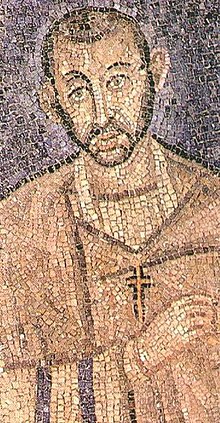

Gratian

Gratian (born April 18, 359 in Sirmium , † August 25, 383 in Lugdunum ), with full name Flavius Gratianus , was emperor in the west of the Roman Empire from 375 to 383 , but was appointed co-emperor by his father Valentinian I in 367 . Together with Theodosius I , he raised Christianity to the state religion in the Roman Empire.

Life

Youth and education

Gratian enjoyed an excellent education, among other things he was instructed by the educator and poet Ausonius . His father Valentinian I ruled the western part of the Roman Empire from 364, while his brother Valens ruled the eastern half. In 367, at the age of eight, after having held the consulate the year before, Gratian received the title of Augustus (co-emperor) after his father's serious illness . Around 374 he married Constantia († 383), the daughter of Constantius II ; after Constantia's death he married an otherwise unknown woman named Laeta.

After the death of his father in 375, Gratian became Emperor of the West. His half-brother Valentinian II was also proclaimed emperor by the troops under the Germanic army master Merobaudes , who was to play an important role at Gratian's court. Gratian agreed to this survey, especially since his brother was still a minor and therefore posed no danger.

Domination

Gratian first settled in Trier , where he stayed for most of his government, later he also resided in Milan, among other places, and celebrated his Decennalia (tenth anniversary of the government) in Rome in 376 . He maintained good relations with the Senate and also promoted Latin literature. Ausonius seems to have exploited his influence on the young emperor to help relatives and friends to get jobs and to increase the influence of the Gallic aristocracy at Gratian's court in general. The departure of Gratian from Trier ended this preference for Gallic aristocrats. But otherwise the daily government work was in the hands of others, so the Praetorian prefect and thus the highest administrative officer Sextus Petronius Probus had an important function.

In the military field Gratian put the steps taken by his father measures to secure the Rhine frontier fort, where he Germanic troops especially appreciated, and devoted himself to the fight against the invading Alemanni , with whom he 378 large to battle of argentovaria near Colmar delivered . Its connected Rhine crossing was the last of a Roman emperor.

In the same year, on August 9, 378, his uncle and eastern co-emperor, the senior Augustus Valens, was defeated and killed by the Goths in the battle of Adrianople . Gratian, who had come with troops from the west to support his uncle, was late. Since sole rule over the entire empire no longer seemed possible and his half-brother Valentinian II was still a child, Gratian then assigned the east to Theodosius I on January 19, 379 , who was pursuing a successful policy overall. However, in the following years it also became apparent that Theodosius tried to outdo his two western co-emperors.

Religious politics

The rule of Gratian is to be seen as a transitional period of the empire from paganism to Christianity and falls at the end of the Arian dispute . Under the influence of Ambrose of Milan, Gratian rejected (probably 382 or 383) the insignia of the Pontifex Maximus , which Constantine and his successors continued to accept.

In the Arian controversy, Gratian was at first wavering, but then, convinced of Ambrosius, especially through his treatise de Fide , took massive action against the Arians and Donatists and forbade their services; he gave the churches back to the Trinitarians. He supported the Orthodox clergy with several laws. From then on all clerics were exempt from burdens and taxes . Otherwise, however, Gratian did not pursue a particularly stringent course in religious policy and was also unable to settle several points of contention (such as the dispute between the bishops Priscillian and Hydatius), which was expected of an emperor.

With the Edict Cunctos populos issued on February 27, 380 together with Theodosius , he ended the religious freedom that Constantine had introduced with the Edict of Milan in 313. He declared the Catholic Orthodox Church to be the only state church .

It is generally believed that Gratian, on the advice of his advisor Ambrosius of Milan (more differentiated, but now Alan Cameron ), cracked down on paganism. In any case, he abolished all privileges of the pagan priests and vestals, including the special rights of their cults, and thus also deprived them of financial resources. In 381 he had the altar of Victoria removed from the Senate meeting room (see dispute over the Victoria altar ). Without government support, paganism gradually lost its influence. In 383, Gratian also declared apostasy (apostasy) to be a crime to be prosecuted by the state.

Usurpation of Magnus Maximus and Death of Gratian

In the spring of 383, a revolt of the Roman troops broke out in Britain under the Spanish-born Magnus Maximus , which encroached on the mainland and spread into Gaul . The background to the rebellion is not entirely clear, because Gratian could look back on a thoroughly successful reign and also had military victories to show, although at the end of his reign he had made himself very unpopular with the army and with parts of the (mostly pagan) senate aristocracy. In the sources it is mentioned that the preference for barbaric Alans caused unrest in the army , which resulted in the usurpation of Maximus, but this may only be an excuse. Gratian had apparently no longer paid sufficient attention to the threatened areas in Gaul and therefore lost his support there, which Maximus took advantage of to reach for the purple.

Gratian was in northern Italy at the time of the usurpation and marched to meet Maximus as soon as he learned of his emperor's rise. There were some minor skirmishes near today's Paris . Maximus had served under Theodosius the Elder , the father of the new Emperor Theodosius. From this time, some of Gratian's troops still had fond memories of Maximus, so it was not difficult for him to convince them to overflow. Gratian soon found himself abandoned by his troops and fled with a few companions to Lyon, where he was caught up with and slain by the army master Andragathius on August 25, 383. Gratian's head was cut off and put on public display.

Gratian's half-brother Valentinian II remained in office, but had to share power in the west with Maximus. Theodosius remained master in the east of the empire. When Maximus invaded Italy in 387 and drove Valentinian II out, Theodosius opposed him, married Valentinian's sister and defeated Maximus in 388, who was murdered shortly afterwards by his own men. Valentinian II committed suicide in 392.

rating

Gratian's reign on the one hand set itself apart from his father's rule (as far as the good relationship with the Senate was concerned), on the other hand it also showed continuity (as far as military and border policy were concerned). According to the sources, Gratian was pious, well educated, and not untalented. Politics, however, was not his primary concern and he appeared to have lacked determination; he was also quite dependent on his advisors, which in part explains his rather fickle internal policy. This is likely to have been the main reason for the discontent in the military that led to the successful usurpation of Maximus.

In the dispute over the Victoria Altar, however, he was entirely on the side of Ambrosius . In addition to his religious policy, the appointment of the capable Theodosius and his overall successful defense of the frontier, even if the emperor as a person was relatively insignificant, is of particular importance. However, his character and personal life seem to have differed positively from some of his predecessors.

reception

The city of Grenoble (Gratianopolis) in France was named in his honor; the current form of the name is the result of a sound shift over the centuries.

swell

The most important narrative sources are Ammianus Marcellinus (main source up to 378, although Gratian has a rather negative attitude), Zosimos (partly flawed and not very objective), the anonymous Epitome de Caesaribus (with not unimportant and absolutely reliable information), the historical work of Orosius and the church history of Sozomenos and that of Socrates Scholastikos . Other important sources are the various laws of Gratian (collected in Codex Theodosianus ) and coins.

literature

- Thomas S. Burns: Barbarians within the Gates of Rome. A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians (ca. 375-425). Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1994, ISBN 0-253-31288-4 (important military history).

- Alan Cameron : The Last Pagans of Rome. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2011, ISBN 978-0-19-974727-6 .

- Alan Cameron: Gratian's Repudiation of the Pontifical Robe. In: Journal of Roman Studies . Volume 58, 1968, pp. 96-102.

- Gunther Gottlieb: Gratianus. In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 12, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-7772-8344-4 , Sp. 718-732.

- Peter Kehne : Gratian. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 12, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1998, ISBN 3-11-016227-X , pp. 598-601.

- Otto Seeck : History of the fall of the ancient world. Volume 5, Primus, Darmstadt 2000, ISBN 3-89678-161-8 (unchanged reprint of the Stuttgart 1921 edition; comprehensive presentation of the history of the event, but partly outdated in terms of interpretation).

- Otto Seeck: Gratianus 3 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume VII, 2, Stuttgart 1912, Sp. 1831-1839.

Web links

- Walter E. Roberts: Short biography (English) at De Imperatoribus Romanis (with references).

Remarks

- ↑ Cf. Hagith Sivan: Ausonius of Bordeaux . New York 1993, pp. 119ff.

- ↑ Brief description with references in Kehne, pp. 599–601.

- ↑ The dating is uncertain (at least between 379 and 383), cf. Cameron, Gratian's Repudiation of the Pontifical Robe and Cameron, Last Pagans of Rome , pp. 51ff.

- ↑ See Cameron, Last Pagans of Rome , pp. 33ff.

- ↑ See on Gratian's religious policy: Gottlieb, Gratianus .

- ↑ Guy Halsall: Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West. Cambridge 2007, p. 186 f.

- ↑ Seeck, Geschichte , vol. 5, p. 167 f.

- ↑ See also the criticism by Ammianus Marcellinus 31,10,18f.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Valentinian I. |

Roman Emperor 367 / 375–383 |

Valentinian II and Magnus Maximus |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gratian |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Flavius Gratianus |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Emperor in the west of the Roman Empire (375–383) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 18, 359 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Sirmium |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 25, 383 |

| Place of death | Lyon |