Dispute over the Victoria Altar

The dispute over the Victoria Altar in the 4th century AD was the final climax in the intellectual dispute between the followers of the traditional Roman state cult and representatives of Christianity , which was soon to become the state religion of the Roman Empire .

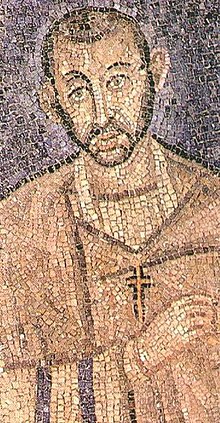

The debate centered on whether or not the altar of the goddess of victory Victoria should be removed from the Curia Iulia , the meeting building of the Senate of Rome . In addition, however, she also touched on questions of mutual tolerance and expressed the fundamental differences between the two religions. The dispute began in 357 with the initial removal and ended in 394 with the final removal of the altar. Its main protagonists were Quintus Aurelius Symmachus , the pagan prefect of Rome, and Bishop Ambrose of Milan . Both tried to convince the adolescent Emperor Valentinian II of their opposing points of view in programmatic writings in 384.

meaning

When it came to the question of removing or rebuilding the altar, the different positions of the two faiths collided in a fundamental way: Influenced by Neoplatonism , Symmachus, as a supporter of the ancient Roman religion, pleaded for a religious tolerance in principle that resulted from his polytheistic ideas. From the point of view of monotheistic Christianity, which saw itself as a revelation religion with an absolute claim to truth, this attitude had to meet with opposition from Ambrosius.

Even if the dispute was ultimately decided in favor of the Christians, the argumentation of Symmachus required fundamental replies from Christian authors, such as the church father Augustine of Hippo , who were supposed to exert considerable influence on late antique and medieval theology and philosophy.

The altar

The altar was dedicated to the Roman goddess of victory Victoria. It included a gilded statue of the winged goddess holding a palm branch and a laurel wreath. The Romans had this statue in 272 BC. Conquered in the war against Pyrrhus of Epirus . In the year 29 BC BC Emperor Augustus had them set up in the Senate building to celebrate his victory at Actium . Since then it has been the custom for the senators to offer the goddess a smoke offering on the specially erected altar before each meeting .

The course of the dispute

The dispute started in 357 when the Christian Emperor Constantius II had the altar removed from the Senate Curia for the first time. His successor Julian , the last pagan emperor who ruled from 361 to 363, reversed this decision, but in winter 382/83 Emperor Gratian again ordered the removal of the altar and statue. At the same time, he cut financial donations to pagan institutions such as the Temple of the Vestals . This was a crucial point in the argument that followed. After all, the dispute was not only about religious issues, but also about the financial endowment of pagan institutions, which until then had been the responsibility of the state. The British ancient historian Alan Cameron particularly emphasized this point: For him, the financial aspect was decisive for the decisions of Gratian and his successor, not so much the influence of Ambrosius. Gratian rejected all petitions from pagan senators for restoration of the altar. The city prefect of Rome, Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, who came from the prestigious Symmachi family and led an embassy of pagan senators to the court in Milan in 382, was turned away due to pressure from Christian senators and advisers to the emperor.

After Gratian's death, Valentinian II confirmed his decision in 384. In the same year Quintus Aurelius Symmachus wrote his third Relatio , which he sent to the imperial court in Milan. In it he asked Valentinian to reverse the decision of his predecessor.

Bishop Ambrosius of Milan, a close advisor to the emperor, opposed the argumentation of this relation with the Christian point of view. He did this first in two letters (nos. 17 and 18) and years later in a third (no. 57). The reason for this could have been the last - historically uncertainly documented - installation of the altar by the usurper Eugenius in 394. Those involved argued comparatively objectively, which in view of the sometimes bloody clashes between pagans and Christians - for example in Alexandria in 391 - was not a matter of course. This may have contributed to the fact that Symmachus had good relationships with Christians, for example with Sextus Petronius Probus , just as Ambrose, who also came from the Roman upper class, conversely had good contacts with pagans.

Symmachus' reasoning

In his third Relatio, Symmachus tied in with the Rome idea , according to which the city was called to world domination. He recalled her glorious past and explained that she owed her ascent to the head of the world to the faithful execution of the state cult and the veneration of the ancient gods. From this point of view, the former military victories were also a result of the worship of the goddess of victory Victoria. The reverse conclusion remained unspoken, according to which devastating defeats in recent times, such as those against the Goths in the Battle of Adrianople in 378, were due to the turning away from the gods. Symmachus only alludes to this with a rhetorical question: "Who would be so friendly towards the barbarians that they would not want the altar of Victoria to be rebuilt?" The renunciation of the cult of Vesta in 383 also caused the famine in the city of Rome. Historical experience and cleverness therefore require adherence to the traditional state cult.

A logical consequence of Symmachus' argument was his demand that state support for the temples be resumed. From the perspective of the pagan Romans, intercourse between humans and gods was a reciprocal give and take with a contractual character. For them, the protection of the state by the gods depended not only on the meticulous execution of the cults, but also on the state itself paying for sacrifices and for the maintenance of the temples and their colleges of priests. In the eyes of a traditionalist like Symmachus, the private execution of state cults must appear completely pointless. Ambrose seems to deliberately misjudge this in his reply when he urges the heathen to get along without state funds, just as the Christians in earlier times. In fact, like other Christian theologians before him, he is likely to have recognized the close connection between the state and state cult as a weak point in the pagan position. If the state stopped funding traditional cults, they lost their original purpose. In this respect, the financial aspects of the dispute also had a religious dimension.

Finally, Symmachus touched on fundamental questions of the relationship between the followers of the individual religions. He was a conservative traditionalist and was rather skeptical of the attempts of his friend, the philosopher Vettius Agorius Praetextatus , who strived for a renewal of belief in gods in the sense of Neoplatonism. Nevertheless, he now made use of these ideas and argued that the differences between Christians and pagans were only external. In any case, there is only one deity behind the various names that people give the gods. But this is - analogous to Plato's theory of ideas , for example in his allegory of the cave - only shadowy and understandable for people to a limited extent. Basically, however, pagans and Christians worshiped the same thing under different names, just as they looked at the same stars. How does it matter how each individual comes to the truth? One way alone does not lead there. In short: Symmachus pleaded for philosophical pluralism and religious tolerance; Admittedly, this tolerant attitude was also due to the fact that the pagan religions towards Christianity increasingly lost their political and cultural significance towards the end of the 4th century. The argumentation of Symmachus with Neoplatonic ideas was clever in that early Christian philosophers and theologians also relied on it, but unlike Symmachus to justify monotheism.

Ambrose's reply

The argument of Symmachus seems to have had an effect at the imperial court. Ambrose therefore countered her energetically in two letters. The bishop, who privately dealt with pagans very friendly and was highly educated, did not give in in principle and finally got his position through.

Ambrosius apparently saw the demand for tolerance as a threat to Christianity's sole claim to truth and therefore used sometimes harsh formulations. The emperor should not be fooled by empty phrases; he has to serve God and faith. For the individual there is salvation only if he adheres to the true, i.e. Christian, faith. Ambrose referred to the persecution of Christians by pagan rulers. Now the side is demanding tolerance, which under Emperor Julian tried a few years ago to push back Christianity. The fact that Christian senators should now also attend sacrifices on a pagan altar is unacceptable. Contrary to the facts, Ambrose claimed that the pagan senators were only a minority in Rome. Symmachus does not demand tolerance, but equality. But how could the emperor reconcile this with his conscience? As a servant of Almighty God, he must not be tolerant of the enemies of true faith. Ambrose even indirectly threatened Valentinian with excommunication - with which the salvation of the young emperor's soul was threatened: If the emperor decided in favor of Symmachus, it would burden the priests heavily. The emperor could continue to attend church, but he would not find a priest there, or at least no one who would not resist him.

If Ambrose had drafted his first reply without precise knowledge of the content of the Relatio des Symmachus, the bishop carefully dealt with his arguments in another letter and tried to refute them point by point. He noted that Rome had previously suffered defeats against foreign peoples. When the Gauls advanced on the Capitol (387 BC), only the cackling of geese, not Jupiter, protected the temples. Also have Hannibal no other gods worshiped as the Romans. So the pagans would have to choose: if their rites had triumphed with the Romans, they would have suffered defeat with the Carthaginians and vice versa. Ambrose therefore denied the connection between earlier successes of the Romans and the old cult order for which Symmachus campaigned so vehemently. According to Ambrosius, the successes were due solely to the proficiency of the Romans themselves. The observance of the cult regulations did not save even an emperor like Valerian , who had Christians persecuted, from getting into captivity. The Victoria Altar was also in the Senate in his day. As for the withdrawal of state funds for the old cults, Ambrosius referred to the early days of Christians, who had to organize without state help: Would the temples have freed slaves or distributed food to the poor? Everything the Church has is used to support the poor. The mos maiorum , the main argument for the advocates of the old cults, had already been discredited by the introduction of foreign deities from the east.

Post-history and effects

In 390, Emperor Theodosius I , who had been in Italy since the suppression of Magnus Maximus, refused a senatorial embassy a renewed request to re-erect the altar. The usurper Eugenius, on the other hand, himself formally a Christian but tolerant of traditional cults, may have allowed the altar to be erected again, although this is controversial in research. However, the attitude of Eugenius, who had temple property returned, was the reason for Ambrosius to argue against it in his 57th letter. The traditional pagan cult celebrations were last celebrated in Rome in 393, but Eugenius was defeated in the Battle of Frigidus in 394 and was killed by soldiers of Theodosius. Theodosius was demonstratively mild towards the vanquished, but no longer allowed the cults to be practiced. Only sparse archaeological remains of the altar and statue have been found in modern times.

The final removal of the altar - whether by Gratian or ten years later by Theodosius - meant a powerful symbolic defeat for paganism. In addition, Theodosius had banned all pagan cults in his sphere of influence as early as 391, thus making Christianity the sole state religion.

At the beginning of the fifth century, however, than during the Great Migration the Visigoths under Alaric I had invaded Italy and 410 Rome had conquered, Symmachus' arguments fell on fertile ground again. Some Romans could only explain the capture of the former imperial capital by so-called barbarians with the apostasy from the old gods. Christian theologians, who had proclaimed since the time of Constantine that the kingdom of God was being realized in the Roman Empire, now found themselves in need of explanation.

The most important theologian and Doctor of the Church of this time was Augustine of Hippo . In 384, when the dispute over the altar reached its journalistic climax, he had come to the imperial court in Milan as a rhetorician. No one other than Symmachus had recommended him for this position, but influenced by his adversary Ambrosius, he finally professed to be Catholic. Under the influence of the catastrophe of 410 Augustine wrote his work De Civitate Dei , in which he explains that the kingdom of God does not manifest itself in an earthly state but in the individual believers who live according to the commandments of Christianity. One of the main works of late antique and medieval philosophy is an answer to the questions that the pagan Symmachus had raised in the dispute over the Victoria Altar.

Sources and translations

- Richard Klein : The dispute over the Victoria Altar. The third relatio of Symmachus and the letters 17, 18 and 57 of Bishop Ambrose of Milan. Introduction, text and explanations (research texts 7) . Darmstadt 1972, ISBN 3-534-05169-6 .

literature

- Herbert Bloch : The Pagan Revival in the West at the End of the Fourth Century . In: Arnaldo Momigliano (Ed.): The Conflict Between Paganism and Christianity in the Fourth Century. Essays . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1963, pp. 193-218.

- Alan Cameron : The Last Pagans of Rome . Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2011, ISBN 978-0-199-74727-6 .

- Willy Evenepoel: Ambrose vs. Symmachus. Christians and Pagans in AD 384 . In: Ancient Society. Volume 29, 1998/99, ISSN 0066-1619 , pp. 283-306.

- Richard Klein : Symmachus. A tragic figure of the outgoing paganism (= impulses of research. Volume 2). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1971, ISBN 3-534-04928-4 (2nd unchanged edition, ibid. 1986).

- Daniel Carlo Pangerl: On the Power of Arguments. The strategies of the Roman city prefect Symmachus and the Bishop Ambrose of Milan in the dispute over the Victoria Altar in 384 . In: Roman quarterly for Christian antiquity and church history 107, 2012, pp. 1–20.

- Friedrich Prinz : From Constantine to Charlemagne. Development and change of Europe . Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf et al. 2000, ISBN 3-538-07112-8 , p. 323 ff.

- Klaus Rosen : Fides contra dissimulationem. Ambrosius and Symmachus in the fight for the Victoria altar . In: Yearbook for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 37, 1994, pp. 29-36.

- Rita Lizzi Testa: The Famous 'Altar of Victory Controversy' in Rome: The Impact of Christianity at the End of the Fourth Century. In: Johannes Wienand (Ed.): Contested Monarchy. Integrating the Roman Empire in the Fourth Century AD ( Oxford Studies in Late Antiquity ). Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-976899-8 , pp. 405-419.

- Jelle Wytzes: The last fight of paganism in Rome (= Etudes préliminaires aux religions orientales dans l'empire Romain. Volume 56). Brill, Leiden 1977, ISBN 90-04-04786-7 (important, but partly outdated historical study of the disputes between Christians and Pagans in the second half of the 4th century in Rome, with Latin text, German translation and commentaries on the third Relatio and the 17th, 18th and 57th letters of Ambrosius).

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Cameron (2011), p. 39ff.

- ↑ Klein (1971), p. 76ff., Especially p. 99ff.

- ↑ See Klein (1971), pp. 20 f. and p. 62 f.

- ↑ See Klein (1971), p. 127

- ↑ Symmachus, rel. 3.9f.

- ↑ See Klein (1971), p. 122ff.

- ↑ Epist. 17, 4

- ↑ Epist. 17, 9f. See also epist. 18, 31.

- ↑ Epist. 17, 16

- ↑ Epist. 17, 13. This is reminiscent of the later confrontation between Ambrosius and Emperor Theodosius.

- ↑ Epist. 18, 5f.

- ↑ Epist. 18, 7

- ↑ Epist. 18, 11ff., Esp. 18, 16

- ↑ Epist. 18, 23, see also Klein (1971), p. 57ff. and 129f.

- ↑ Epist. 18, 30

- ↑ Cf. Joachim Szidat: The Usurpation of Eugenius . In: Historia 28, 1979, pp. 487-508, here p. 500.