Lex Ripuaria

The Lex Ripuaria (also Lex Ribuaria ) is a collection of legal texts written in Latin that was published at the beginning of the 7th century during the reign of the Austrasian King Dagobert I for the area of the Duchy of Ripuarien (area of the Rhine Franks). The collection of laws was based on the law of the Salian Franks ( Lex Salica ) from the years 507 to 511, but emphasized traditional Franconian law. In contrast, the Lex Salica also contained extensive legal regulations for the Roman or Gallo-Roman population.

The Ripuarians

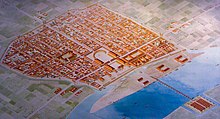

The Rhine Franks , next to the Sal Franks or Salians, the most important sub-tribe of the Confederation of Franks , which had been declared since the 3rd century , had moved up the Rhine from the Lower Rhine in the 4th century and attacked the Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (Cologne) and the Roman colony in the fall of 355 Conquered at the beginning of the 5th century. The inhabitants - Romans , Gallo- Romans and largely Romanized remains of the Germanic Ubier - were absorbed in the Rhine Franconia in the following generations, provided they had not fled. Around the year 500 the first known small king Sigibert of Cologne ruled over Cologne and parts of the Rhineland; From around the 6th century on, the name Ripuarier came up for the Rhine Franconians .

Dagobert I.

The Fredegar chronicle reported Dagobert I as the last king of the House of the Merovingian, not yet in the shadow of coming after him to power home Meier stood. In 623 Dagobert was appointed subordinate ruler in Australia by his father Chlothar . Although the salfränkischen line of Merovingian entstammend, he was recognized by the Ripuarian francs as king. In the year 629 he became king of the whole empire with the capital Paris . With this he also had Burgundy and Aquitaine under his rule and became one of the most powerful in the line of Merovingian rulers .

Legal content

The Lex Ripuaria summarized orally handed down law of the Rhine Franconia. The 89 chapters, especially those of the second part (of three parts), were strongly influenced by the Lex Salica , which the Merovingian Clovis I had published between 507 and 511 as the code of the Salian Franks . In addition to the law of the Franks, the Lex Salica also included regulations on the position of the church, the Roman ( Gallo-Roman ) population and the coexistence between Franks and other ethnic groups. Ripuarian law emphasized the traditional Franconian legal conceptions - many Rhine Franconians were still caught in pre-Christian beliefs and later converted to Christianity than the vast majority of Salians. Regulations of the funeral system, the grave goods and the equipment of warriors (Brünne = bruina; helmet = helmo; greaves = bagnbergae) are handed down by the Lex Ripuaria. Questions of everyday life and nature were also regulated in the Lex Ripuaria. So was z. B. the hazel magic prohibited. The fruits of the hazel were considered an elixir of love and were used to promote fertility. The hazel bush was ascribed powers against lightning and earth rays, hazel rods were used as divining rods and hazel branches were used to ward off witches and evil spells . Despite the ban, the hazel customs persisted into the high Middle Ages. A special feature of the Lex Ripuaria was the recognition and regulation of the so-called court battle (duellum) between opponents, usually in front of an audience. These duels did not appear in the Lex Salica.

Both Lex Ripuaria and Lex Salica knew wergeld (man money), an atonement that had been created to curb blood vengeance and the resulting permanent feuds between the clans. For members of the Franconian people different sentences than for "non-Franconians" (Romans and Gallo-Romans) applied. For the killing of a franc, double the Wergeld was due as for a Roman living in a comparable position.

The wergeld was z. B .:

- 100 solidi for a free Roman (romanus possessor)

- 100 solidi for one half-free franc (lidi)

- 200 solidi for one free franc (franci)

- 300 solidi for followers from the Gallo-Roman population (convivae)

- 600 solidi for the mounted Frankish followers of the king (Antrustionen)

- 600 solidi for a priest

- 900 solidi for a bishop

In the wergeld for one (killed) franc, in addition to the portion that had to be paid to the family of the person concerned, a “tax portion” of 1/3 was due for the tax authorities. 2/3 went to the clan, half of them to the immediate relatives, the other half to the relatives as Magsühne . Since the Roman population did not know the term of the clan , this proportion did not apply to this group, which relativizes the wergeld ratio somewhat.

Standing at the head of the people

- The King (Rex Francorum)

- his symbols of power were the spear, browband and signet ring

- the people paid homage to their king through the so-called "oath of subjects"

- The nobility consisted of the dukes (dux) and counts (comes)

- The military service consisted of the " Leudes ".

Only the male line was entitled to inheritance, after the sons the brothers, with priority if the sons were considered "not capable of governing".

The population was divided into classes u. a .:

- Free (ingenui, Franci) (the single Frankish man, conscript)

- Semi-free (liti, lidi)

- Freedmen (liberti)

- Servants, unfree (servi)

- Roman (Free Roman = Romanus Possessor, member of the middle class)

- Roman servants (colone)

From the term “Franci” for the (individual) Free (Franconian), the adjective “franc” for “free” emerged over the years in Romansh-speaking countries - from which the German equivalent was borrowed around the 15th century.

Unlike z. For example, in the relationship between the ( Arian-Christian ) Goths and their Roman ( Catholic-Christian ) roommates, there was no statutory ban on marriage between the Franks and other ethnic groups.

structure

Rudolph Sohm examined the Lex Ripuaria in detail in his publication “On the Origin of the Lex Ribuaria” and compared it with the Lex Salica .

Sohm found the oldest references to a Lex Ripuaria in the prologue to the Lex Bajuvariorum . It reports on the law of the Austrasian Franks such as that of the Alemanni and Bavarians . The first writings of the Lex Ripuaria date from the time of Theuderich I , additions were made under Childebert I and Chlothar I, as well as a revision under Dagobert I , who is considered to be the editor of the complete version.

The Lex Ripuaria was divided into three parts (with an appendix as part four):

- Part 1 (Chapters 1 to 31; with few references to the Lex Salica ):

- Composed under Theuderich I. - 511 to 533 king in the east of the Franconian Empire .

- In this part u. a. Wergeld rates and fines for bodily harm and killing of the free and unfree are set. The punishment of “serious theft” with death can also be found in the first part.

- Part 2 (Chapters 32 to 56; contains almost unchanged parts of the Lex Salica ):

- The origin lies in the time of Childebert I. (about 558), Chlothar I. (558-561) and Childebert II. (575-596).

- In this part u. a. Procedures and process regulations are dealt with, from complaints to evidence judgments to execution. Also rules about what should happen if a defendant does not appear in court or evades the court by fleeing. Whoever does not pay his wergeld will die. Such peculiarities are also regulated, for example when B. the master has to pay for the deeds of his slave. Although almost complete parts of the Lex Salica have been taken over, some passages have been left out completely (which were already dealt with in Part 1).

- Part 3 (Chapters 57 to 89; extensive, incomplete use of the Lex Salica ):

- Originated at the time of Dagobert I (623 king in Australia, 629–638 total king).

- This part contains important provisions on public law, the positive and negative duties of subjects. This is how the king's right to ban is treated (king's ban, military ban, call to arms) to which the free and freed are subject - as well as the penalties for non-compliance. Insults and attacks against the king and his family, incitement to rebellion and apostasy from the Frankish Empire are punishable by death .

The fourth part (appendix to the Lex Ripuaria) contains a list of additional penalties and newer terms for criminal offenses and perpetrators (for example, the term outlaw appears). This part is considered a product of the Carolingian era , possibly published by Karl Martell . Even at the time of Charlemagne , there were further Carolingian reviews .

Overall, the Lex Ripuaria can be regarded as an update of the Lex Salica, with adjustments to the law of the Ripuarians where it was considered necessary.

Its model, the Lex Salica, gained importance beyond the Merovingian period to the time of Charlemagne. A number of laws, such as the regulation of the succession to the throne (to the male successor), lasted for the European ruling houses into the high Middle Ages and were still valid for some monarchies into modern times .

literature

- Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand : Lex Ribuaria. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 18, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2001, ISBN 3-11-016950-9 , pp. 320–322.

- Rudolf Sohm: About the origin of the Lex Ribuaria . Hermann Böhlau publishing house, Weimar 1866

- Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century . CH Beck, Munich 1970

- Werner Böcking: The Romans on the Lower Rhine . Klartext, Essen 2005, ISBN 3-89861-427-1

- Bruno Bleckmann : The Teutons . CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-58476-3

- Renate Pirling : The Roman-Franconian grave fields of Krefeld-Gellep . Museum Burg Linn, Krefeld 2011

- Tilmann Bechert, Willem JH Willems: The Roman imperial border from the Moselle to the North Sea coast. Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1189-2

Web links

- Lex Ribuaria in the repertory "Historical Sources of the German Middle Ages"

- The lex Ribuaria in the Bibliotheca legum regni Francorum manuscripta , manuscript database on secular law in the Franconian Empire ( Karl Ubl , University of Cologne ).

- Lex Ribuaria in the LegIT project ( digital recording and indexing of the vernacular vocabulary of the continental West Germanic Leges barbarorum in a database )

Individual evidence

- ↑ F. Beyerle: Völksrechtliche studies I-III, Journal of Savigny-Stiftung, germ Abt.. LXII 264vv, LXIII ivv; Forever 450vv; 487vv

- ^ Werner Eck: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. Greven Verlag, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 586-627.

- ↑ Patrick J. Geary: The Merovingians . Munich 2003, p. 154ff.

- ↑ Margarete Weidemann: On the chronology of the Merovingians in the 7th and 8th centuries . In: Francia 25/1, 1999, p. 179ff.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the 6th century , Verlag CH Beck, Munich, pp. 105, 123

- ^ Rudolf Sohm: About the origin of the Lex Ribuaria . Verlag Hermann Böhlau - Weimar 1866, pp. 1 to 82

- ↑ F. Beyerle: Völksrechtliche studies I-III, Journal of Savigny-Stiftung, germ Abt.. LXII 264vv, LXIII ivv; Forever 450vv; 487vv

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the 6th century , Verlag CH Beck, Munich, p. 161 ff.

- ↑ Johannes Hoops: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, Volume 14 , P. 35 ff

- ^ Rudolf Sohm: About the origin of the Lex Ribuaria . Verlag Hermann Böhlau - Weimar 1866, pp. 1 to 82

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, pp. 115-119.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century . CH Beck - Munich 1970, pp. 117, 162, 146 - 207

- ^ Rudolf Sohm: About the origin of the Lex Ribuaria . Verlag Hermann Böhlau - Weimar 1866, pp. 1 to 82

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century . CH Beck - Munich 1970, pp. 117, 162, 146 - 207

- ^ Rudolf Sohm: About the origin of the Lex Ribuaria . Verlag Hermann Böhlau - Weimar 1866, pp. 1 to 82

- ^ Karl August Eckhardt: The laws of the Carolingian Empire 714–911 / I. Salian and Ribuarian Franks . Verlag Böhlau, Weimar 1934, (Germanic rights. Texts and translations, revised 1953, 2, 1)