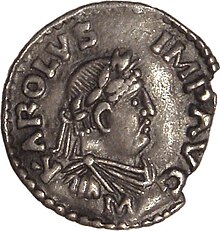

Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( Latin Carolus Magnus or Karolus Magnus , French and English Charlemagne ; * probably April 2, 747 or 748; † January 28, 814 in Aachen ) was King of the Frankish Empire from 768 to 814 (together with his brother Karlmann until 771 ). On December 25, 800, he was the first Western European ruler since antiquity to achieve the imperial dignity , which was renewed with him. The grandson of the mayor of the palace , Charles Martel was the most important rulers of the sex of the Carolingian. Under him, the Frankish empire reached its greatest expansion and power.

Karl managed to secure his power in the Franconian Empire and to expand it considerably in a series of campaigns. The Saxon Wars , which lasted from 772 to 804 with interruptions, were particularly fierce and fought with great losses . Their aim was the submission and forced Christianization of the Saxons . Charles also intervened in Italy and conquered the Longobard Empire in 774 . A campaign directed against the Moors in northern Spain in 778 failed. In the east of his empire he ended the independence of the tribal duchy of Baiern in 788 and conquered the remaining Avars in the 790s . The borders in the east against the Danes and Slavic tribes and in the southwest against the Moors were secured by the establishment of brands . The Franconian Empire rose to become a new great power alongside Byzantium and the Abbasid Caliphate . It comprised the core part of early medieval Latin Christianity and was the most important state structure in the West since the fall of Western Rome .

Karl ensured effective administration and endeavored to implement a comprehensive educational reform that resulted in a cultural revitalization of the Franconian Empire . The political high point of his life was the coronation as emperor by Pope Leo III. at Christmas of the year 800. It created the basis for the western medieval empire . He is counted as Charles I in the ranks of both the Roman-German emperors and the French kings . His main residence, Aachen, remained the coronation site of the Roman-German kings until the 16th century .

1165 he was from the antipope Paschal III. canonized ; the day of remembrance in the Catholic and Protestant Church is January 28th. Karl is considered one of the most important medieval rulers and one of the most important rulers in European historical consciousness ; During his lifetime he was called Pater Europae ("Father of Europe"). His life was repeatedly thematized in fiction and art, with the contemporary image of history being the starting point.

Life

Childhood and youth

Karl came from what is now known as the Carolingian family, which had only held the Franconian royal dignity since 751 , but had already been the determining power at the royal court in the decades before. Their rise began in the 7th century and resulted from the growing weakness of the Merovingian kingship , with real power increasingly passed into the hands of the caretakers . These were originally only administrators of the royal court, but gained more and more influence over time. The Arnulfingers and Pippinids , the ancestors of the later Carolingians , played an important role as early as the 7th century . Their power base was in the eastern part of Austrasia . From the time of Pippin the Middle and his son Karl Martell , they finally determined Frankish imperial politics. The later name of the family as "Carolingian" goes back to Karl Martell.

Charlemagne was the eldest son of Pippin the Younger , the Frankish house merchant and (since 751) king, and his wife Bertrada . The date of his birth is April 2nd, which was recorded in a calendar of the Lorsch Monastery from the 9th century . The year of birth, on the other hand, has long been controversial in research. In the meantime, based on a more precise evaluation of the sources, the year 747 or 748 has been proposed. The place of birth, however, is completely unknown, all attempts to determine it are speculative.

In 751 Karl's brother Karlmann was born, in 757 his sister Gisela († 810) followed, who in 788 became Abbess of Chelles . The names that Pippin gave his sons are striking. Although they can be traced back to the names of Pippin's father (Karl) and brother (Karlmann), they were otherwise isolated in the naming of the Arnulfinger-Pippinids. They were also not based on the Merovingian naming as the names of later Carolingian kings (Chlotar became Lothar, Clovis to Ludwig). Pippin probably wanted to illustrate the new self-confidence of his house.

The biography written by Karl's confidante Einhard - today often referred to as Vita Karoli Magni - represents the main source of Karl's life alongside the so-called Annales regni Francorum (Reichsannalen) , but it skips childhood, about which almost nothing is known. Modern research can also only make a few concrete statements about the factual “unknown childhood” of Charles.

At the beginning of the year 754, Pope Stephan II crossed the Alps and went to the Franconian Empire. The reason for this trip were the increasing attacks of the Lombard king Aistulf , who had conquered the exarchate of Ravenna in 751 . Formally, this area was under the rule of the Byzantine emperor, but Constantine V , who fought successfully against the Arabs on the Byzantine eastern border and was bound there, refused to intervene in the west at that time. Thereupon Stephan turned to the most powerful Western ruler and tried to persuade Pippin to intervene.

The presence of the Pope north of the Alps caused a sensation, because it was the first time that a bishop from Rome went to the Franconian Empire. At the meeting in the Palatinate of Ponthion , the Pope appeared as a seeker. Pippin entered into a friendship alliance (amicitia) with him and promised him support against the Lombards. Pippin also benefited from the alliance, who had only held the Frankish royal dignity since 751 after he had defeated the powerless last Merovingian king Childeric III. had dethroned. The alliance with the Pope helped Pippin to legitimize his kingship, at the same time the Franconian kings became the new patrons of the Pope in Rome, which had far-reaching consequences for further developments. At a further meeting with the Pope at Easter 754 in Quierzy , Pippin was able to announce the Frankish intervention in Italy and guaranteed the Pope several (also former Byzantine) territories in central Italy, the so-called Pippin donation , which formed the basis for the later Papal State. A specific papal consideration followed shortly afterwards, because in 754 Pippin and his two sons were anointed by Stephen II in Saint-Denis to be kings of the Franks, which gave the new Carolingian kingdom an additional sacred character. All three also received the high Roman honorary title Patricius from the Pope . Shortly thereafter, Pippin successfully intervened in Italy in favor of the Pope, which, however, met with resistance from the Byzantines, as they viewed this as an intervention in their domain.

There are also isolated references to Karl's youth in the sources. In addition to mentions in petitions for the family in Pippin's name, Karl is mentioned by name twice in his father's documents, referring to his official capacity to act. In 763, Pippin also seems to have transferred several counties to his sons.

Furthermore, at least some general conclusions can be drawn about Karl's youth and upbringing. It can be assumed that in his upbringing not only the usual Frankish warrior training, which was essential for a king as a military leader, but also a certain education was emphasized. It is unclear whether he was taught the full program of the septem artes liberales , the seven liberal arts, which he later attempted to restore as part of his educational reform and is assessed differently in research. Karl spoke Franconian from home , but he certainly received Latin lessons. Even in the Merovingian era, a certain education was by no means unusual for high-ranking aristocrats. Although the level of education had declined in the 8th century, Latin was omnipresent at court, in administration and in worship . In contrast to many of the later East Franconian or Roman-German kings, Karl apparently also understood Latin. According to Einhard, he spoke it like his mother tongue, which may be an exaggeration. He is also likely to have read Latin. In any case, Karl was a quite educated ruler for the time and was interested in education all his life.

Assumption of power

King Pippin spent the last years of his reign securing the outskirts of the Frankish Empire. He led campaigns in the former Visigothic Septimania and in 759 conquered Narbonne , the last Arab outpost north of the Pyrenees . Pippin's nephew Tassilo III. kept a certain independence in Bavaria . Aquitaine, on the other hand, was incorporated into the Franconian Empire in 768 after several campaigns.

On the way back from Aquitaine, Pippin fell seriously ill in June 768, after which he began to sort out his inheritance. He died in Saint-Denis on September 24, 768. Shortly before his death he had decreed that the empire should be divided between his sons Karl and Karlmann. According to Einhard, the division was based on the previous division of 741 between Karl Martell's sons, but it did not coincide with her. Charles received Austrasia, most of Neustria and the west of Aquitaine, Karlmann the rest of Aquitaine, Burgundy , Provence , Septimania, Alsace and Alamannia . Bavaria was excluded from the division of the estate and remained in fact independent. In this way, Karl's empire surrounded that of his brother in a semicircle in the west and north. On October 9, 768, the day of remembrance of Dionysius of Paris , each of the brothers was anointed king in his part of the empire, Karl in Noyon and Karlmann in the old Merovingian residence of Soissons .

Karl and Karlmann did not exercise joint rule over the Franconian Empire, but ruled independently of one another in their respective empires, which can be seen in their documents. Their relationship seems to have been strained from the start. There are indications of limited cooperation, for example with regard to a Roman synod in March 769, but this was the exception. Both acted in a power-conscious manner and competed with one another. Both became fathers in the same year (770) and each named their son after their father Pippin. The break became obvious when Karlmann refused to support his brother in 769 against the rebellious Aquitaine, where Huno (a) ld had revolted against Carolingian rule. Karl finally threw down the uprising alone, Hunold was taken prisoner, and then also moved in the part of Aquitaine that was formally under Karlmann.

In the period that followed, tensions increased. The mother Bertrada tried to mediate between the warring brothers, but soon lost her influence on Karl. He had initially consented to a marriage arranged by his mother with a Lombard princess whose name was unknown , for which he separated from his first wife, Himiltrud. Bertrada seems to have striven for a comprehensive alliance system: In addition to the alliance with the ambitious Longobard king Desiderius, which was reinforced by her marriage, her plan also included Tassilo, who was already married to another daughter of Desiderius. The concerns of Pope Stephen III. who was deeply alarmed by the sudden Frankish-Lombard rapprochement, tried to refute it. It is possible that Karlmann was also involved in the new alliance system promoted by Bertrada and probably some Franconian greats ; his wife Gerberga may have been a relative of Desiderius.

However, in the spring of 771, Karl changed his political plans and broke with his mother's conception. He sent his Lombard wife back to Desiderius, which was an affront for him. Instead, Karl took an Alamanness named Hildegard as his wife. This had to worry Karlmann, because Alemannia belonged to his domain, where Karl now apparently wanted to gain influence. By rejecting all his mother's plans, Karl acted independently for the first time.

An open confrontation between Karl and Karlmann, which had become more and more likely, was prevented by Karlmann's surprising death on December 4, 771. Karl immediately took power in the empire of the deceased, whose greats paid homage to him in Corbeny in December 771 . The assumption that Karl was involved in the death of his brother because he profited significantly from it is not supported by the sources. The claim that Karlmann's memory fell victim to a damnatio memoriae ("destruction of memory") is not correct; that Karlmann was buried in Reims rather than Saint-Denis is very likely due to his own wish. What is certain is that Karl now ruled unrestrictedly in the Franconian Empire. Karlmann's widow Gerberga and her children fled to Desiderius in Italy.

Military expansion and integration

Longobard campaign and incorporation of Italy

After Karlmann's death, Karl had consolidated his position in the empire, but the two sons of his brother, who had fled to the Longobard Empire with their mother and some of the Franconian greats, were a potential threat. In northern and central Italy the political situation came to a head. Desiderius had appropriated territories to which the Roman Church lay claim. In the spring of 773, envoy of Pope Hadrian therefore asked at the court of Charles for the support of the papal protective power against the Lombards. Karl did not hesitate and decided on a large-scale Lombard campaign, similar to what his father had undertaken about two decades earlier. Unlike Pippin, however, Karl planned to conquer the entire Lombard Empire and integrate it into the Frankish Empire, as Einhard noted. The historian Bernard Bachrach, who specializes in early medieval military history, believes, however, that Karl did not want the war against Desiderius from the start; It was only the development of the situation in Italy that prompted him to intervene.

In the late summer of 773 Karl moved from Geneva to Italy with two large Franconian troops . One he led himself over the Col du Mont Cenis , the other his uncle Bernhard led over the Great St. Bernhard . Desiderius found himself in an untenable position and withdrew to Pavia . Karl had the heavily fortified city besieged. Only after nine months did Pavia capitulate at the beginning of June 774 and was plundered by the Franks. Charles occupied the entire Longobard Empire and incorporated it into the Frankish Empire. From then on he called himself King of the Franks and the Lombards without a new coronation; this title is first attested in a document dated July 16, 774. Desiderius, his wife and daughter were probably imprisoned in a monastery at Corbie Abbey . The Lombard king's son Adelchis was able to escape to Constantinople . When there was a conflict between the Franks and the Longobard princes in Spoleto and Benevento in 787/88, the Byzantines brought Adelchis into play. But this was only a short episode; the Lombard princes accepted the Frankish suzerainty again and took action against the Byzantines, whereupon Adelchis had to give up all plans. The Lombard principalities in lower Italy remained effectively withdrawn from Charles's access, while Upper Italy and parts of central Italy belonged to the Franconian Empire from then on and later, as Imperial Italy, were also part of the Roman-German Empire.

In 773, Gerberga and her two sons fell into Karl's hands during an advance on Verona. Her further fate is unknown. Karl probably had his nephews eliminated or imprisoned because of their claim to the paternal inheritance.

At Easter 774, Charles suddenly appeared before Rome with his retinue, while his army was still besieging Pavia. Pope Hadrian was completely surprised by this. The Popes had always refused direct access to the city for the Longobard kings, but Hadrian apparently did not want to anger the Frankish rulers and new patrons of the papacy. The Frankish king was received in a ritual manner 30 miles from the city, the protocol being based on the reception of the Byzantine exarch, the highest military and civil administrator of the Byzantine emperor in Italy. Karl was escorted to St. Peter's Church, where Hadrian received him with a large crowd. The Pope and the King met each other with honor and assured each other of their mutual friendship. Karl is said to have asked for formal permission to enter the city, which he was allowed to do. Subsequently, the Frankish king and Roman Patricius moved into the former imperial city on the Tiber, which in the Middle Ages only had a fraction of the ancient population, but whose monumental buildings still had an impressive effect on visitors. Apparently, Charles strove to symbolically respect the position and authority of the Pope. The renewal of the Pactum , the agreement concluded by Pippin with the papacy with regard to papal territorial claims, was of real political importance . Spiritual and secular violence, the two universal powers of the Middle Ages, seemed to work together harmoniously. In the days that followed, Charles took part in all religious rituals in Rome before leaving the city.

The Saxon Wars

In the summer of 772 the Saxon Wars, which lasted up to 804 with interruptions, began. The still pagan ("pagan") Saxons did not know any central ruling institutions and did not live in a closed imperial union like the Franks and Lombards, but only in loosely organized tribal associations (Westphalia, Ostfalen, Engern and Nordalbingier). The Saxons had repeatedly come into conflict with the Franks before, as their tribal area was directly adjacent to the north-eastern Franconian dominion.

Einhard describes Karl's campaigns against the Saxons as the longest, cruelest and most strenuous fighting for the Franks to date. He condemns the Saxons as idolaters and enemies of Christianity, but does not name the goal of Karl's campaigns as the Christianization of the Saxons, but rather the elimination of this military threat on the Frankish border. Karl Martell and Pippin had already undertaken limited campaigns against the Saxons without attempting to convert them. In modern research, however, Charlemagne's Saxon Wars are viewed as missionary wars. Einhard and the Reichsannalen convey a rather tendentious picture of the Saxon Wars, while from the Saxon side only late reports from the time after Christianization are available. In contrast, timely letters, poems and rulers' edicts convey snapshots of the Saxon wars and show that the outcome was open for several years. What is certain is that this "Thirty Years War" required military campaigns almost every year. Even for a military society like the Frankish one, in which the king always had to prove himself as a military leader and where the booty and forced tributes were of economic importance, this was an enormous burden.

The war began in 772 with a Frankish advance deep into the Saxon tribal area. Karl advanced from Worms to the Eresburg and conquered it. Then the Franks came to the (probably central) Saxon cult sanctuary, the so-called Irminsul , which Karl had destroyed. The destruction of the Irminsul fits perfectly into the image of a missionary work that was planned at least in the future in 772, but pure lustfulness is also conceivable as a motif. The Franconian advance, which was also supposed to relieve tension between some of the Franconian greats and the king, had been successful for the time being. But this was only an apparent victory, especially since the decentralized tribal organization of the Saxons made it much more difficult for the Franks to control. The Saxons took advantage of the absence of the king, who was in Italy in 773/74, and devastated Franconian territory in 774 in what is now Hesse, with several Christian churches and monasteries being attacked. Karl invaded Saxony with a large army in 775 and forced the submission of the Engern (under Bruno) and the Ostfalen (under Hassio / Hessi); the Westphalia were also defeated. The king apparently proceeded with great brutality during this campaign: the imperial annals near the court reported three bloodbaths that Karl had caused in 775, and according to the North Humbrian annals he raged among his enemies. Karl's reaction to the breach of contract by the Saxons was the slogan that there could only be baptism or death for the Saxons. At this point in time at the latest, Karl regarded the Saxon campaigns as a missionary work, because in the revised version of the Reichsannals, the so-called Einhardsannals , it is noted that the war against the Saxons will continue until they have submitted to the Christian faith or have been exterminated.

In 776 there was another Saxon uprising, which was also suppressed. The Eresburg was rebuilt and the Saxons had to take hostages. Karl had further bases built in Saxony, including the so-called Karlsburg (civitas Karoli) , which was later destroyed and then rebuilt as Pfalz Paderborn . In the following years churches and monasteries were founded in order to force the missionary work of Saxony and to consolidate the Frankish rule. In 777, the situation in Saxony seemed to be so much under control that the king could hold an imperial assembly in Paderborn . This was a spectacular demonstration of Frankish rule, the first imperial assembly outside the Franconian heartland. At this point in time, the Franks apparently believed themselves to be the complete winner. In the same year there were repeated mass baptisms, some of which, contrary to church law, took place under duress; In addition, there were Frankish tax claims, which represented an additional burden for the Saxons from the Frankish foreign rule. In 778, the Saxon Widukind appears for the first time as a new leader of the rebels who continued to oppose Frankish rule; it was not primarily nobles who were involved, but free and semi-free, while parts of the Saxon nobility came to terms with the conquerors. The time for a renewed uprising seemed opportune, because Karl had suffered a severe defeat in Spain that same year. Karl now viewed the Saxon resistance as a departure from the Christian faith, and the Saxons involved were treason for him. The harder he reacted. As early as 778 he gathered troops, in the summer of 779 he defeated the Saxons near Bocholt in one of the rare open battles of this conflict. Karl penetrated further into Saxony and received the submission of several rebels who again had to take hostages.

In 780 and 782 , Karl again held imperial assemblies in Saxony. The Saxon resistance seemed broken. Saxon aristocrats were involved in Frankish rule and rewarded, and a Frankish-Saxon troop contingent was even to be deployed against the Slavs. Then in 782 large parts of the Saxons rose again under the leadership of Widukind. On the Süntel in the Weser Uplands they defeated a Frankish troop contingent, which is concealed in the original version of the Reichsannalen, but admitted in the Einhardsannalen. Karl hurriedly marched to the Weser to stifle the uprising. Some of the rebels submitted again, but at Verden an der Aller there was still the so-called blood court of Verden in 782 : According to the Reichsannalen, 4,500 Saxons were killed on Karl's orders. This process has received a lot of attention in research to this day. The number 4500 may be clearly exaggerated, but it is indisputable that Karl took an extremely brutal measure in Verden, which contributed a lot to the darkening of his image for posterity, even if the number of Saxons killed may be significantly lower. Since a similar action did not take place later, the "blood court" will have served primarily as a deterrent. In the same year, the Franconian county constitution ( see below ) was introduced in Saxony, hostages were again placed and Saxony deported. The so-called Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae was also enacted, which stipulated severe punishments (often the death penalty) for deviations from the Christian faith, attacks on Christian dignitaries or institutions, and for pagan cult activities.

In 783 the Franks defeated the Saxons in two battles. At the end of 784, Karl moved back to Saxony in winter to secure his rule. In the following year further campaigns were carried out, the Saxon resistance had now been brutally broken and Karl offered Widukind talks. Widukind agreed and submitted to the Frankish king; he was even baptized at Christmas 785 in the Palatinate Attigny , with Karl acting as his godfather. The Saxon resistance flared up in the following years, but did not reach the extent of the first phase of the Saxon Wars. In 792 riots broke out again and between 793 and 797 Franconian troops had to deploy regularly, but these battles mainly took place in northeastern Saxony in the Elbe region. The Franks consolidated their rule in Saxony, Christianization and church organization were promoted and several deportations were carried out. The Frankish rule was now largely secured. The "sovereign terror" criticized by Alkuin , which had apparently been pursued in a targeted manner, could therefore be softened. In 797 the Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae was replaced by a milder regulation. In 802 with the Lex Saxonum written law was issued for the Saxons, which also incorporated elements of their tribal law. In 802 and 804 there were further Franconian campaigns in the northern Elbe region. Saxon residents were deported from there to the eastern Franconian Empire, instead of them Franconians were settled in the Elbe region. The Saxon Wars were now finally over. Saxony remained Christian and was integrated into the Carolingian Empire not least through the involvement of the local elites.

Spain

While Karl's early expansion policy was hard-won (as in Saxony), but overall it was extremely successful, 778 was a year of crisis in his reign. At the imperial assembly of Paderborn in 777 unexpectedly high-ranking ambassadors from the Arab-ruled Iberian Peninsula ( al-Andalus ) appeared. The Umayyad Abd ar-Rahman I , who escaped the Abbasid overthrow and fled to Spain, had established a rule there that was independent of the new caliph in Baghdad , the Emirate of Cordoba . In this empire there was strong tension between Arabs and Berbers. The opposition included the Arab Wali Suleiman al-Arabi. Together with two other envoys in Paderborn, he asked Karl for assistance against Abd ar-Rahman. In return, the three great Arabs submitted to the Frankish king. This gave Karl an opportunity for further expansion, especially since the Franks had already been involved in battles with Arab troops on several occasions. As early as 759 an Arab governor seems to have offered King Pippin his submission.

In the following year (778), Karl undertook a campaign to northern Spain. As a justification he used Arab raids, at least that is how he put it in a letter to the Pope; he was also able to act as a protector of the Spanish Christians. He divided the army into two divisions: one first advanced on Pamplona , the other on Saragossa . The Christian King of Asturias viewed Charles' campaign rather suspiciously, perhaps he even came to an understanding with the Emir of Córdoba. Pamplona, the capital of the Christian Basques, was conquered, but the advance on Saragossa, where the Frankish army reunited, was unsuccessful. The sources for the Spanish campaign are extremely poor, but Abd ar-Rahman's position of power evidently proved to be stable and the opposition directed against him was not sufficiently strong. Al-Arabi provided hostages and Barcelona and other cities were placed under Charles's rule, but these seem to have been purely formal subjugations that had no consequences and did not bring the Franks any profit. Obviously, Karl only had insufficient ideas about the conditions in Spain, he miscalculated his chances of success. When he received the news of the renewed uprising in Saxony, he broke off the already failed campaign and began to retreat.

As he retreated, Charles had the walls of Pamplona destroyed, but the Basques took revenge for his harsh actions. In August 778 they ambushed the Frankish army and inflicted considerable losses on the rearguard in the battle of Roncesvalles . The Reichsannals conceal the defeat of Charles, but in the revised version, the Einhard Annals, it is mentioned. Along with other Frankish nobles, Hruotland , Count of the Breton Marks , also fell . His death served as the material for the very popular Roland song recorded in the 12th century .

The events of the Spanish campaign, glossed over in pro-Carolingian sources, are rated as a complete failure in research. Nevertheless, Karl was later to become active again in northern Spain, this time with more success. In 792/93 there were Arab incursions into the Frankish empire, whereupon the Franks undertook campaigns to northern Spain. Several fortified cities could be captured, including Barcelona (803) and Pamplona (811). Christians were settled in the conquered area. The Franks had thus established a strategically important buffer zone, which was only established as a regular border county, the Spanish mark , after Charles' death .

Avar war

In the southeast the Franconian Empire bordered the Avar Empire . The Avars were equestrian nomads from the Asian steppe region who had appeared in the field of vision of the Byzantines in the late 6th century and who had established a powerful empire in the Balkans by the early 7th century. An Avar embassy to Karl is documented for the year 782. Although the Avar Empire had long since passed its zenith in the late 8th century, the Avars undertook raids into the Franconian Empire in 788, including northern Italy and Bavaria. These advances may have been triggered by requests for help from opposition circles in the Franconian Empire or arose from the Avars' fear that they would be the next victim of Karl's expansionary policy. The Avar advance failed in any case, and no agreement could be reached in the subsequent negotiations in Worms 790.

Whether Karl wanted to stabilize the border in the south-east or was simply out for conquest, in 791 a large-scale Frankish invasion of the Avar Empire began. Einhard describes the following war as the greatest of Charles besides the Saxon Wars. The Avar War was also of great symbolic importance because it was waged against “pagans” and Charles was able to stylize himself as a Christian ruler. In the 791 campaign, the Avars evaded the Franks, who used a large river fleet on the Danube to supply the army. In the following years Karl planned another campaign. In this context, a canal was also built ( Fossa Carolina ). Initially, however, renewed uprisings in the Saxony prevented the project. In 794/95 there were internal power struggles in the Avar Empire, which resulted in the death of the ruling khagan . In 795 a delegation from an Avar group appeared completely unexpectedly on the Elbe and offered Karl the submission of their leader, the Tudun . He accepted Karl as overlord and was even baptized the following year.

In 796 a Frankish army marched again into the Avar Empire and made rich booty (so-called Avar treasure ); the new khagan submitted to the Franks. The power of the Avars was broken and their empire was falling apart. In 799/803 there was an uprising against the Frankish suzerainty, but this remained ineffective, especially since the Franks did not intervene in the internal structures of the Avar Empire. Christianization and resettlement were promoted in the border area. Avar ambassadors are mentioned again in the sources for the year 822, but the Avar empire itself was in a final process of dissolution. The Franks now moved the border area directly into the empire and organized a border mark, this time to defend themselves against the Bulgarians who had established a new empire in the Balkans.

The end of Bavaria's independence

After Karl took over his brother Karlmann's part of the empire at the end of 771 and successfully intervened in Italy in 773/74, there was only one empty space in the Carolingian Reichsverband: Bavaria, where Tassilo III. , a nephew of King Pippin, ruled as Duke. Tassilo had been an allegiance to Pippin and had taken part in a campaign against the Lombards in 756. Subsequently, however, he took over the independent power of rule in the Duchy of Bavaria from 757. Hardly anything can be said more precisely about the following years. The records of the Carolingian imperial annals about Tassilo were made in retrospect and should above all show his behavior in an unfavorable light. There it is reported that the duke swore an oath to King Pippin in 757 and broke it in 763 by " deserting " ( old high German harisliz ) during a campaign in Aquitaine . In modern research, this representation is generally not believed, especially because of the subsequent process and the political background. If it were true, the Bavarian Duke would have been promptly called to account, because such behavior was punishable by death.

Tassilo came from the old and noble family of the Agilolfinger . Bavaria has enjoyed a special role in the empire since the Merovingian era. As a duke, Tassilo appeared self-confident. He married the Longobard Princess Liutberga and had very good relations with the Pope. He exercised his sovereign power in Bavaria extensively, not least in the church area. At that time, there was also lively cultural activity in Bavaria. In fact, Tassilo enjoyed a position similar to a king in his duchy and even documented it in 769 based on the Carolingian royal statute. However, Karl did not tolerate any political competitors. Therefore, his action against the Agilolfinger, on which he decided relatively late, was the consequence of his policy.

In 787 Tassilo was summoned to Worms, where he was supposed to submit to the Frankish king. The Bavarian Duke did not appear, however, and tried to mediate with the papal. Soon, however, he had to realize that not only was the Pope completely in line with Charles and calling on him to submit to complete submission, but that he now had little support even in his own duchy. When Karl was still taking military action against Tassilo in 787, several Bavarian greats went over to the Franconian side. Tassilo was isolated and submitted to Karl in October 787, to whom he now also swore an oath of allegiance. Gerd Althoff interpreted this process as the earliest occurrence of the ritual deditio (submission). Nevertheless, tensions remained and Karl now apparently saw a favorable opportunity to clear up the situation in his mind. In June 788, Tassilo was summoned to Ingelheim and arrested there with his family. He was accused of making pacts with the Avars; there was also the accusation of "desertion". Profrankic Bavarian nobles testified against the duke, who was sentenced to death. Karl converted the sentence into lifelong monastic imprisonment. In 794 Tassilo was briefly released from monastery custody in order to publicly express repentance again at the Synod of Frankfurt and to waive his claims in a document.

In modern research there is no doubt that the allegations against Tassilo were fabricated and that a sham political trial took place in Ingelheim. For political reasons, Karl had decided to end the unpleasant special position of the powerful Bavarian Duke. He did not want to tolerate a royal-like sideline within his sphere of influence. Tassilo's rule quickly collapsed, as he had opponents in his duchy who expected more from working with Karl. The official point of view of the Carolingian royal court is especially visible in the description of the imperial annals, in which an easily understandable "chain of evidence" of the alleged offenses of Tassilo was listed and the duke was portrayed as an unfaithful follower. Bavaria retained a certain special position in the period that followed: it remained a church unit and the county constitution was not introduced in administration either, but the government was handed over to a royal prefect. Politically, however, it finally became part of the empire.

The imperial coronation

Since 795 Leo III. Pope in Rome. During this time, the papacy came under the influence of the Roman city nobility, which was split up into various factions and was decisive in the papal election. Leo was accused, among other things, of an unworthy lifestyle, but above all he had no political support from the urban Roman nobility, and his situation became increasingly precarious. At the end of April 799, the confrontation between the Pope and the nobility came to a head in such a way that an assassination attempt was made on Leo, behind which confidants of the previous Pope Hadrian I stood. Leo survived and fled to Karl in Paderborn . The Paderborn epic describes these processes .

Karl gave Leo military support and had him returned to Rome at the end of 799. In the late summer of 800 Charles himself went to Italy, at the end of November he appeared in Rome. There it happened on Christmas Day, December 25th, 800, in Alt-St. Peter for the imperial coronation of Charlemagne by the Pope. This set in motion an extremely powerful development for the rest of the Middle Ages: the transfer of Roman rule to the Franks ( translatio imperii ). The Roman empire in the west, where the last emperor in Italy had been deposed in 476, was renewed with the coronation of Charles. In this context aspects of salvation history played an important role; the Roman empire was considered the last world empire in history ( doctrine of the four kingdoms ). Now there was a new "Roman Empire", which was linked to the claim to rule of the ancient Roman emperors and was claimed first by the Carolingians, then since the Liudolfingern (Ottonen) by the Roman-German kings. Without being able to estimate the scope, Karl laid the foundation stone for the Roman-German Empire . These are the certain facts, but essential details of the imperial coronation are unclear.

There are a total of four reports on the process of the imperial coronation: in the Lorsch Annalen , in the Liber pontificalis , the Reichsannalen and in Einhard. In essence, the protective function of Charles against the Church and the Pope is praised there. The people were enthusiastic and the imperial coronation was more of a spontaneous act. Einhard even claims that Karl would not have entered the church if he had known about Leo's plans.

However, these descriptions are considered inaccurate in modern research. It is considered impossible that the preparations could go unnoticed, that Karl could have stayed away from the church on Christmas Day and that a coronation he did not want could have been carried out. Rather, it was Karl himself who for some time had been working specifically towards the coronation and the renewal of the Roman Empire in the west. Although the Pope acted as a coronator, he was in an extremely weak position and was entirely dependent on Karl's support. As emperor, Karl took on the role of judge over Leo's Roman opponents.

The creation of the Western Empire was favored by several factors. In the east there was still the empire of the Byzantines, who called themselves " Rhomeans " (Romans) and could look back on an uninterrupted state continuity to the late ancient Roman empire. In the year 800, however, the Empress Irene was ruled there (which was viewed disparagingly in the West) who had to struggle with numerous domestic political problems. From a Carolingian perspective, the so-called "Empire of the Greeks" - a provocative designation for the Byzantines - was taken into account, but judged derogatory; an alleged transfer of the empire from Byzantium to Charles was even constructed. In Byzantium, however, Karl was viewed simply as a usurper and maintained the exclusive claim to the “Roman” empire. It was not until 812 that an understanding was reached regarding the two emperor problem . The coronation of the emperor in the year 800 was also significant in terms of salvation history, as end-time expectations were widespread, which were connected with the Roman idea of empire. At a time when the religious was decisive in determining thought, the coronation of the emperor received such an eschatological component.

External relations

Karl maintained foreign relations that reached from England to the eastern Mediterranean. Einhard goes into this aspect in his biography of the ruler and briefly describes the wide-ranging Carolingian diplomacy. The possibilities of foreign policy at that time, the main instrument of which were embassies, should not be overestimated, but the contacts gave the court an insight into a much wider world.

In the context of more recent studies, however, it becomes clear how relatively limited the creative power of the empire of Charles was, after all, the most powerful system of rule in Latin Europe since the fall of Western Rome, compared to other great empires of this time. A simple example makes this clear: In 792, Karl ordered the construction of a 3 km long canal in Middle Franconia that would have connected the Rhine and Danube river systems. However, the construction work soon got stuck, so that in 793 the construction was canceled. In contrast, in 767 much more extensive construction projects in Byzantium (where water pipes were repaired over a distance of more than 100 km) and in the Caliphate ( round city of Baghdad , whose construction over 100,000 workers were involved) succeeded without major problems. In the China of the Tang Dynasty, on the other hand, a canal around 150 km in length was built according to plan in 742/43. All of these empires had universal claims to rule, similar to the Carolingian empire after Charles' coronation; however, the resources and the creative leeway based on them were much more limited in the case of Karl.

The Anglo-Saxon England was divided into several competing empires, including the Franks talked traditionally good relations. Among other things, Karl was in (not always tension-free) contact with the powerful King Offa von Mercien , who temporarily achieved supremacy in England. The later King Egbert of Wessex stayed for some time at Charles' court. According to Einhard, the Scottish rulers even recognized Charles' supremacy.

In the east and, after the conquest of Saxony, also in the northeast, the Franconian Empire bordered the territory of the Slavs . These did not form a closed unit, but were split up into individual trunks. The work of the " Bavarian Geographer " from around 850 lists the Abodrites , Wilzen , Sorbs and Bohemia, among others . At the beginning of the 780s, Slavic attacks on Franconian territory are documented, such as a Sorbian invasion in 782. In the following period, there were repeated individual Franconian campaigns in Slavic tribal areas. The larger Frankish offensive under Karl's command in 789, which was directed against the Wilzen under Dragowit on the other side of the Elbe, where Dragowit's main castle was besieged and he finally had to submit. Under the leadership of the emperor's son Charles the Younger , in 805 and again 806 Franconian, Bavarian and Saxon armies invaded Bohemia. On the other hand, individual Slavic tribes also functioned as Frankish allies; the most important were the Abodrites. In 808 the Wilzen attacked the Abodrites and the east of Saxony in alliance with the Danes, but were defeated in 812. Karl renounced systematic Christian missionary work in the Slavic regions. In this area he did not seek territorial expansion, but only wanted to secure the imperial border and pacify the adjoining domains. In research, Karl’s Slav policy is rated as much more defensive than his approach in the other border areas of the Frankish Empire. For the purpose of securing the border, he wanted to achieve a formal subjugation of the Slavs and loose dependencies of the tribal areas concerned, similar to what the Romans and Byzantines strived for on the borders of their empires.

In general, material motives played an important role in the Frankish campaigns. Timothy Reuter was able to prove that booty (praedae) from targeted looting during military campaigns and regular tribute payments (tributa) were structural features of the Carolingian Empire. In addition to material possessions, this income also included slaves. The tributes went straight to the king. Such income was an important motive for military actions, for example against Saxons, Avars and later against the Slavs. The Carolingians did not have a standing army. Rather, their troops were mobilized as needed, with armored cavalry being of great importance. Every free person in the Franconian Empire was obliged to serve in the army , although the estimates of the total strength differed widely. The prospect of booty was an important incentive for the troops deployed. At the same time, military successes secured the Franks a hegemonic position vis-à-vis weaker neighbors such as the Slavic tribes and gave the victorious king additional legitimacy in the Frankish warrior society. However, Bernard Bachrach recently questioned the economic significance of the income from looting and tribute payments.

In 804 the region north of the Elbe, which was forcibly evacuated by the Saxon population, was assigned to the Abodrites. It was soon hit by attacks by the Danes, who, according to the Reichsannals, had sent embassies to the Franks in 782 and 798. Under Gudfred , the Danes in 804 and 808 made forays into the northern border area by ship, in 810 a large fleet raided the Frisian coast. The Franks saw themselves forced to take over the border protection in this area again. The construction of Esesfeld Castle, ordered by Karl, served this purpose . In 811 and 813 peace treaties were signed with the Danes. After Karl's death, however, there were repeated, this time much more serious, raids by the Northmen against the Frankish Empire. As early as 799, Norsemen (Danes or Norwegians) carried out raids on the Gaulish Atlantic coast, which highlighted the maritime inferiority of the Franks. On the other hand, there were also trade relations with the northern neighbors; In the time after Karl, the missionary efforts were also promoted.

The Frankish empire had had loose contacts with the caliphate since the time of King Pippin. One aspect was the wish of the Franconian rulers to secure access for Christian pilgrims to the holy places. In 797, Karl made contact with Hārūn ar-Raschīd , the caliph of Baghdad from the Abbasid family . Einhard gives the caliph's name correctly as Aaron and emphasizes that he ruled the entire east except India; Notker's later report on the embassies, on the other hand, is already heavily embellished with legend. Hārūn ar-Raschīd actually ruled over a vast area that stretched from North Africa across the Middle East to Central Asia. The caliph gave Karl an Asian elephant named Abul Abbas , which the Jewish long-distance trader Isaak brought to the Frankish Empire in 801. The exact background of the diplomatic mission is unknown, but the pilgrimages and the protection of Christians in the Caliphate were probably the subject of the negotiations. In 802 a second Frankish embassy was sent to Baghdad. This time, Charles's new self-image as emperor and protector of Christian sanctuaries (as in Jerusalem) was clearly decisive. This was followed in 807 by a return embassy from the caliphate, which brought rich gifts to Karl. The relationship between the emperor and the caliph was good, and trade relations also benefited. Possibly, alliance considerations against Byzantium played a role. After the death of the caliph, however, the situation of Christians in the caliphate deteriorated and relations between the two kingdoms ebbed.

In the course of Charles' contacts with the Lombard principalities of southern Italy, which are still independent, a loose contact was established with the Muslim Aghlabids in what is now Tunisia. Charles maintained more intensive relationships with Spain, for example with Muslim rulers (which led to the fatal failure of the Spanish campaign in 778) and with the Asturian King Alfonso II .

Relations between the Frankish Empire and Byzantium were intense, even though the relationship had been heavily burdened for several years since Charles' coronation as emperor in 800, because now the so-called two- emperor problem arose : Both sides claimed to be in the footsteps of the Roman emperors and raised one connected universal validity. Nikephorus I , Byzantine emperor ("Basileus") since 802, felt that Charles was presumptuous and refused to recognize it. The conflict intensified when Charles incorporated the regions of Dalmatia and Veneto, which had been claimed by Byzantium, into his sphere of influence. There was limited fighting, but both sides were fundamentally interested in a compromise: Charles was still bound by the borders, while the Byzantines were threatened by the Bulgarians in the west and by the Caliphate in the east. Karl had already sent a letter to Constantinople in 811, but Nikephorus was killed shortly afterwards. In the Peace of Aachen (812) a viable compromise with his successor was Michael I. achieved. In 813 Karl sent him a new letter in which he addressed him as his venerable brother. The great importance of the contacts between the Frankish Empire and Byzantium can also be seen in the quite high number of embassies: a total of four Frankish and eight Byzantine embassies are documented during Charles's reign.

Court and rulership practice

The court was the center of stately activity. The early medieval kings were traveling kings who traveled with the court from Palatinate to Palatinate and regulated government affairs on the way. The money economy played a role in the early Middle Ages and coins were minted almost continuously, even in the time of Charlemagne. Nonetheless, natural economy dominated in the Franconian Empire ; the material basis of kingship was the crown property . Karl maintained a large number of palaces, which were scattered over the empire, temporarily functioned as royal residences and served to supply the royal court. The places visited included those that were already favored by the Frankish kings in earlier times, but new places were added under Karl, for example in the conquered areas. The focus of his travel routes, the ruling itinerary , was in the northeast, especially in the region between the Meuse and the Rhine-Main area. The number of stays varies greatly and ranges from a single (albeit important) stay in Frankfurt am Main to 26 stays in Aachen . Aachen was probably because of the nearby forest areas, in which the king could pursue his passion for hunting, and because of the hot springs Karl's favorite residence; after 795 he stayed in other places only three times during the winter. In the Paderborn epic - ignoring Byzantium - even touted as Roma secunda , the second Rome, and in an eclogue by the Franconian scholar Moduin as the future “golden rebirth of Rome”, Aachen now functioned as the main royal residence. Extensive construction work was carried out on site, including the establishment of the magnificent Aachen Royal Palace .

The work De ordine palatii by Archbishop Hinkmar von Reims from 882 gives an insight into the structure of the courtyard. In the administrative area at the court, the court orchestra , which the capellanus presided over, played an important role. Then there were the chancellor and the notaries. These were all clergy, while the Count Palatine regulated secular affairs and also belonged to the king's closest advisory group. In addition, a large number of servants worked at the court, including the chamberlain, the cupbearer , the quartermaster, the seneschal and other domestic staff ("house servants"). Not to be underestimated is the importance of the queen who presided over the royal household.

The court was not only a political center, but also an important cultural center. Charlemagne himself was evidently interested in culture and deliberately gathered several scholars from Latin-speaking Western and Central Europe at his court. The most respected of them was the Anglo-Saxon Alcuin (died 804). Alcuin had previously been director of the famous cathedral school in York ; he owned an extensive library and enjoyed an excellent reputation. He met Karl for the first time in the winter months of 768/69 and in 782 followed the call to his court, where he not only worked as an influential advisor, but also rose to head the court school. There were also a number of other educated people like Einhard. He was initially a pupil of Alkuin, later head of the court school, confidante of Charles and worked as his builder. After the death of Charles, he wrote his famous biography of the emperor, which was based on ancient models. Peter von Pisa was a Latin grammarian who was also appointed to the Karlshof and gave Karl Latin lessons. The Lombard scholar Paulus Diaconus had served as a king in Italy and had come to Charles's court in 782, where he stayed and worked for four years. The Patriarch Paulinus II of Aquileia had a wide range of knowledge. Theodulf von Orléans was an extremely well-read and educated Visigoth theologian and poet. He wrote the Libri Carolini for Karl . From Ireland came the scholars Dungal and Dicuil , who were engaged in scientific studies. In his cultural endeavors, Karl was able to rely on other people in his environment, including Arn von Salzburg , Angilbert , the brothers Adalhard and Wala , who were related to the ruler, and his sister Gisela (died 810, Abbess of Chelles since 788). The court and the court school gave impulses for a cultural renewal, whereby the Carolingian church was reformed as the central cultural carrier.

As a rule, court days were called twice a year as meetings of the king and the greats of the empire to clarify pending political questions or to settle disputes. In the early Middle Ages, rule was essentially tied to individual persons; there were in fact no "state institutions" (and thus no abstract concept such as statehood) apart from these personal structures of rule. Nevertheless, the Carolingians established an administrative structure that was relatively effective for contemporary conditions. Karl removed the last remains of the older tribal duchies , with Tassilo III. the last Duke was deposed in 788. The administration in the empire was now (as in some cases in Merovingian times) mainly in the hands of the counts . These not only acted as military leaders, but also as royal officials in the exercise of the regalia within the framework of the so-called county constitution . In certain areas they were representatives of the king (margraves, castle and palatine counts). The margraves achieved particular importance : In their office, various competencies were bundled in the new border stamps , where they had extensive special rights. The transfer of offices and property to selected aristocratic families secured their loyalty and founded a new imperial aristocracy that participated in the royal rule; In the time of Charles, it was not yet a question of hereditary, but conferred offices. The Carolingian Empire was a multi-ethnic empire over which the Franks did not rule alone, but in which other ethnic groups were also integrated. The so-called royal messengers (missi dominici) were supposed to serve a more effective penetration of rule . These were sent in pairs, a secular and a spiritual messenger (usually a count and a bishop) to enforce instructions and edicts and to collect taxes, but also to demonstrate the royal presence and for on-site inspections. If necessary, they could exercise direct power and pass judgments in an assigned district. It was the missi who accepted the oath of allegiance that all male residents of the empire from the age of twelve had to take to the king in 789. With this, Karl endeavored to further secure the loyalty of his subjects. The oath was requested again in 802.

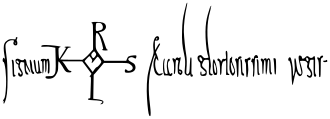

In addition to the stately infrastructure, the basis of effective administration was the written form. The number of issued certificates can serve as an indicator of the sovereign penetration of the Reich territory. 164 documents from Charles that are regarded as genuine have survived, but these are only the original or copies of the far more numerous documents that Karl issued. Some of the content of lost documents can be obtained from other preserved sources ( Deperdita ). The early Merovingian kings initially employed mainly laypeople who were literate, but in the following years writing and reading skills were only imparted to clergymen. Knowledge of writing in the Franconian Empire had been declining since the 7th century, and Latin became increasingly wild. Charles' so-called educational reform not only served to revitalize the culture, but was also an important element in ensuring efficient rule. Charles' reforms aimed at a comprehensive reorganization in the ecclesiastical, cultural and manorial realms.

An important instrument of royal rule was legislation, which Charles made extensive use of. With the so-called capitularies a largely uniform legislation was created, the judiciary and the judiciary were also reformed. A famous source for economic history, especially for agriculture and horticulture, is the Land Estate Ordinance Capitulare de villis vel curtis imperii , which Charlemagne issued as a detailed regulation on the administration of crown estates . With this he obviously wanted to ensure a smooth supply of the royal court. In March 789, Charles issued the chapter Admonitio generalis . It was a "programmatic capitular" that included a general exhortation and was directed against ills in the Church and in the kingdom. In 82 chapters the church reorganization, the revitalization of knowledge and the fight against heresy and superstition were dealt with, and generally a better way of life of the subjects was worked towards. Peace and unity were promoted, undesirable factors such as hatred, envy and discord were condemned, with several direct instructions addressed to the clergy and relatively few to all subjects. These admonitions and orders were part of a comprehensive reform program, which included the educational reform and which Karl did not develop himself, but significantly promoted and promoted. The entire life in the empire was to be based on the program of the Admonitio generalis , the implementation was entrusted to the missi .

However, Karl did not achieve complete success with it. This is not only due to the inadequacy of his means of rule, but also to the desires and encroachments of the great. Karl recognized that the existing conditions often actually set limits to his ideas of order and law, and responded to this, for example by trying to reorganize the missi in 802 . In his capitularies, Karl emphasized, among other things, the protection of the free and sometimes denounced ecclesiastical desires. The protection of the poor (pauperes) was part of the royal catalog of tasks, and Karl tried to at least partially improve the living conditions for the poorer classes and also for unfree people, who even had certain opportunities for advancement. The Jews , some of whom were traditionally active as long-distance traders, enjoyed royal protection.

Church politics

The church played a prominent role in the reorganization and strengthening of the interior, as it had an additional infrastructure that spanned the entire empire. The interplay between royalty and church was not a fundamental innovation, as this was generally of particular importance in the early Middle Ages. The Merovingians had already included the church in their conception of rule and the early Carolingians had built on this. Karl also pushed this process through the massive expansion of the clerical infrastructure. Numerous new monasteries were founded and dioceses established, with Charles reserving the right to appoint the bishops himself. Furthermore, Karl gave the church extensive donations and favors, and church reforms were also carried out. The introduction of the Metropolitan Constitution , the regular holding of synods in the presence of the king and the carrying out of visitations strengthened the bond between the king and the Church. The comprehensive educational reform of Charles affected above all the church, which benefited from the increase in the level of education and from the measures to eliminate church grievances.

Karl saw himself not only as a patron of the church, but also as the lord of the imperial episcopate . He had great influence on church issues. In general, he was able to rely on the bishops, who mostly came from the local noble families and played an important role in both the spiritual and secular areas. Faith and politics were often closely linked in the Middle Ages. Karl, who also bore the title defensor ecclesiae (“Defender of the Church”), was not only a believer, he was also anxious to translate his role as Christian ruler into real politics. This is reflected in numerous decrees of the emperor, not least in the context of the pronouncements on educational reform, where the use of the written word in worship was of central importance. In a letter from Alcuins to Pope Leo III, probably written on behalf of Charles. From the year 796 it becomes clear that the emperor gave high priority to the fight against the "infidels" abroad and the consolidation of the faith within. Karl relied on an active missionary policy, especially in Saxony. This was sometimes carried out with considerable violence, something which Alkuin, for example, who insisted on the voluntary nature of faith, explicitly criticized. In addition, according to church doctrine, a person first had to be instructed in the faith before they volunteered to do so. The converted Saxons had only been introduced to Christianity very superficially, while strict laws were supposed to ensure compliance with them; a reinforced mission to the Saxons began after 785. Inside, Karl urged his subjects to lead a Christian way of life, a stronger "Christianization of society", for example with regard to compliance with the ten commandments and the Sunday commandment.

The center of Carolingian church politics had been Aachen since the end of the 8th century, although there was no bishopric there. After 794 synods were only held in Aachen in the presence of the king. In the years that followed, Charles repeatedly took care of church problems at synods. While the iconoclast erupted in Byzantium in the 8th and 9th centuries , in the Franconian Empire the synod of Frankfurt in 794 dealt with religious image worship, which was ultimately rejected. The reform of the liturgy based on the Roman model initiated by Pippin was continued. At the Council of Aachen (809) the so-called Filioque formula was declared binding. Charles' son and successor Ludwig the Pious continued this tradition and held further synods in Aachen before the Carolingian central authority broke up in the struggles for the succession.

The cooperation with the papacy practiced since Pippin's reign was continued, from which both sides profited greatly. Pope Stephan II had legitimized the new Frankish royal family, while the Franks acted as the pope's new secular protective power. However, the source reports vary about the circumstances of the first meeting between Pippin and Pope Stephen II in 754. In the continuation of the Fredegar Chronicle (Continuatio Fredegarii) it is described that the then five-year-old Karl the Pope hurried with a delegation to greet Stephan II in the Frankish Empire and to accompany him to Ponthion in the Palatinate . There Pippin and several Franconian greats received rich gifts from the Pope. The report in Stephen's biography in the Liber Pontificalis deviates from this on one crucial point. Accordingly, Charles also met the Pope here, but Pippin also received the Pope in a solemn ceremony an hour's walk from the Palatinate in Ponthion and even threw himself to the ground in front of him. This deviation is due to the respective character of the sources, in which the corresponding rituals were interpreted differently to the readers and the king or the pope was emphasized.

Karl took advantage of opportunities to increase his own influence. In 773/74 he undertook the Italian campaign to protect the Pope from the Lombards, but largely incorporated the conquered areas into his empire. The fundamental question of how the relationship between the Frankish king and the Pope was structured became more topical after the imperial coronation at Christmas 800, for which Karl himself had worked. The empire and papacy were both universal powers and neither side could accept a formal subordination to the other without being contradicted. But at the time of the imperial coronation, Charles was in a much more favorable political position, while Pope Leo III. was de facto dependent on the emperor due to his weak position in Rome. However, shortly after Charles's death, the papacy gained new room for maneuver. The papacy reached a new high point under Nicholas I in the 9th century, a certain "world position" before papal influence declined in the late 9th century and the papacy in the following period from urban Roman circles and then often from up to the early 11th century strong emperors was dominated.

Carolingian educational reform

In the Franconian Empire, the Latin language was in the 7th / 8th centuries. Century became increasingly "wild", the Proto-Romanesque Vulgar Latin had moved far away from the "classical" ancient Latin in both morphology and syntax . The church educational institutions also fell into disrepair. Knowledge of Greek was barely available in the West, but correct Latin also had to be learned from novels. The linguistic decline in the Carolingian Empire was stopped by targeted measures to promote culture and vice versa since the end of the 8th century. This new boom phase is often referred to as the Carolingian renaissance . The term “ renaissance ” is very problematic for methodological reasons. In the Franconian Empire it was not a question of a “rebirth” of classical ancient knowledge, but only a purification and standardization of the existing cultural property. For this reason, the Carolingian educational reform is nowadays referred to as the Carolingian era . The aim was to renew the “wisdom of the ancients”, whereby the basis of early medieval education in the West was formed by the septem artes liberales known from late antiquity . The reform of the Frankish Church by Boniface in the middle of the 8th century probably gave the impetus for the educational reform . This cultural renewal was also promoted by external impulses, since the spiritual life in England and Ireland had already experienced a revival and the literary culture was increasingly strengthened, as the work of the Beda Venerabilis in the early 8th century shows. Anglo-Saxons like the educated Alcuin also played a role in the scholarly circle of the so-called court school.

Karl himself was by no means uneducated and was very interested in culture. He promoted the educational reform as much as possible, but the implementation was largely due to Alcuin's achievement. The key term for this was correctio . This meant that the Latin script and language, i.e. the basis for the cultural and spiritual discourse in the Latin West, as well as the worship service, had to be "corrected". The existing educational material should be systematically collected, maintained and disseminated. The establishment of a constantly expanding court library also served this purpose . In the famous Admonitio generalis from 789, the educational program is also explicitly addressed. Among other things, the monasteries were warned to set up schools, to pay attention to the education of the priests and to the correct reproduction of the texts when copying; What needs to be corrected is to be corrected. The reform of the monastery and cathedral schools was also important for religious reasons, as the clergy had to rely on the most precise language and script knowledge possible in order to interpret the Vulgate , the Latin version of the Bible, and to be able to create theological writings. This is a central idea of the reform: clarity of the written and spoken word is essential for effective worship. In this way, “science” was placed at the service of faith. The written Latin language has been cleaned up and improved. The Carolingian minuscule , which was well suited as a cursive script, became the new font . Great emphasis was placed on grammar and spelling, correct according to ancient standards, which raised the stylistic level.

In the ecclesiastical field, among other things, the liturgy was revised , collections of homilies were created, and observance of ecclesiastical rules was demanded. There were also changes in the administrative area. The church educational institutions received increased support. In addition, a revised version of the Vulgate was made, the so-called Alcuin Bible . Older writings were looked through and corrected, copies made and distributed. The court school became a teaching center, which radiated across the entire Franconian Empire. Several monasteries were newly founded or experienced a significant boom, including St. Gallen , Reichenau , St. Emmeram , Mondsee and Fulda . They were the main promoters of the educational reform and have therefore been expanded many times. In the Fulda monastery, for example, a distinctive literary culture developed under Alkuin's pupil Rabanus Maurus . In addition to the royal court, several monasteries and bishops played a central role in the educational reform. Research has identified 16 “written provinces” in addition to the Aachen court for the period around 820, each with several scriptoria .

The educational reform ensured a significant strengthening of intellectual life in the Franconian Empire. After the sharp decline since the 7th century, literary production increased noticeably, and art and architecture also benefited from it. Ancient Latin texts that were still preserved by both pagan and Christian authors were now increasingly being used, read, understood and, above all, copied, whereby the effort for the book production was not insignificant. Important ecclesiastical texts were cleared of linguistic overgrowth and made available in sample copies for reproduction. From the court library rare texts were made available to the cathedral and monastery libraries for copying. Book stocks were viewed and recorded in writing in catalogs, and new libraries were set up. Ovid and Virgil were particularly in demand, and Sallust , Quintus Curtius Rufus , Suetonius and Horace , among others , were increasingly being read again. The Carolingian educational reform was therefore of great importance for the transmission of ancient texts. To a large extent, these have only survived because they were copied and thus saved as part of the educational reform. The copying activities sharpened the knowledge of Latin at the same time, so that there was also a qualitative increase in Latinity. Furthermore, Karl had "barbaric" (ie Germanic, vernacular) "old heroic songs" written down, but the collection has not been preserved. The educational reform also strengthened the development of vernacular literature , such as Old High German. Centers of old German tradition were later among others the monasteries Fulda, Reichenau, St. Gallen and Murbach. The Hildebrandslied , an Old High German hero song (around 830/40), has been preserved in fragments .

The time of the Carolingian educational reform was also a heyday of art, especially goldsmithing, which includes the so-called talisman of Charlemagne , and book art . The great importance of culture and art at the court of Charlemagne, where this development was strongly encouraged, was expressed in numerous works. Emerged in several workshops of the Empire (often in division of labor processes) precious and masterfully "illuminated" (illustrated) manuscripts , as in the famous palace school of Charlemagne in Aachen, also known as Ada School known in particular by the Ada Gospels became famous . This production includes the Godescalc Evangelistary , which was made at the beginning of the 780s. Among other things, the Dagulf Psalter and very probably the Lorsch Gospels were written at the court school . The group of artists who worked in Aachen for some time gave a strong impetus and created the Vienna Coronation Gospel Book , which founded its own group . The style of Carolingian book art varies according to the group involved; Reminiscences of works of late antique and Byzantine book illumination occur again and again . In addition, ornate, gem-studded and often decorated with ivory relief carvings were made for the manuscripts .

Death and succession

On January 28, 814, Charlemagne died in Aachen . Einhard reports that the otherwise good state of health of the emperor has deteriorated in his last years. At the end of January 814 Karl suddenly suffered from a high fever, and there was also pain in his side; possibly it was pleurisy. Karl fasted and believed that he could cure the illness in this way, but he died shortly afterwards and was buried in the Aachen Palatine Chapel. It is controversial whether he was buried in the so-called Proserpine sarcophagus back then . The exact location of the original burial place in or on the Palatine Chapel is unknown. According to Einhard's report, a gilded arcade arch with a portrait of Charles and an inscription was placed over the grave .

Karl had suffered from fever attacks since 810, and in the following year he made his personal will. In view of his deteriorating health, he was concerned for the welfare of the empire in his final years. He had made early arrangements for his death. In 806 he wrote a plan for the division of the empire in a political will, the so-called Divisio Regnorum .

After his two older sons had died, however, in September 813 Karl had raised his son Ludwig , who had been sub-king in Aquitaine since 781, to co-emperor and (probably following the Byzantine model) waived the Pope's participation. Father and son were not particularly close, but Ludwig was the last remaining son from Karl's marriage to Hildegard and thus the next legitimate candidate. All this shows that Karl tried very hard to ensure the smoothest possible transition. However, during the reign of Ludwig, the imperial unity was to break up due to internal conflicts . This led to the emergence of Western and Eastern Franconia , the "germ cells" of what later became France and Germany.

The bones of Charles are sealed in a shrine in Aachen Cathedral. The left tibial bone was made available to researchers in 2010, which was examined by scientists led by Frank Rühli, head of the Swiss Mummy Project at the University of Zurich. They estimate the height of Charlemagne at 1.84 meters. In 2019, Frank Rühli and the anthropologist Joachim Schleifring published an analysis of Karl's bones.

Marriages and offspring

Karl was certainly married four times, possibly five marriages. High nobility weddings were primarily political connections. However, nothing is known about the origin of Karl's first wife, Himiltrud. She gave Karl a son who was given the lead name Pippin . Pippin, who evidently saw himself as being neglected within the hierarchy in the empire, rose unsuccessfully against Charles in 792. He was then imprisoned in Prüm Abbey and died in 811. Charles's second wife was the daughter of Desiderius , King of the Lombards ; her real name is unknown, in research often Desiderata is given. This marriage took place as part of the plans of Karl's mother Bertrada, but Karl disowned his Lombard wife in 771.

Instead, shortly afterwards, he married the very young Hildegard , who came from the Alemannic nobility. She bore him a total of nine children, four boys (Karl's later successor Ludwig and Karl , Lothar, who died as a toddler, and another son named Pippin ) and five girls ( Rotrud , Bertha , Gisela and the two Adalhaid and Hildegard, who died as toddlers). Karl's marriage to Hildegard and the queen herself are highlighted particularly positively in the sources. Karl was particularly fond of Hildegard; she accompanied her husband on several trips and is even referred to in a certificate, completely untypical, as dulcissima coniux (“very sweetest wife”). She died in 783.

After only a short period of mourning, Karl married Fastrada in the autumn of 783 . Theodrada and Hiltrud, who died young, came from this marriage . Contrary to the rather negative statements of Einhard, Fastrada is viewed positively in research; Karl himself was evidently closely connected to her. Fastrada fell ill in 794 and died that same year. Shortly thereafter, Karl possibly entered into a fifth and final marriage to Luitgard , who died in 800. However, it is not clear from the source evidence that it was a regular marriage. However, there is no doubt about their position of power at Charles's court.

In addition to his religiously legitimate connections, Karl had numerous concubines. Madelgard, Gerswind , Regina and Adelind are known by name. This was incompatible with church norms and did not fit what is expected of a Christian emperor, but such behavior was not unprecedented. The cohabitation already played a not unimportant role in Merovingian times. Contemporary secular law and sometimes even church law around 800 also offered freedom with regard to married life. Nevertheless, Karl's behavior was fundamentally contrary to church expectations. With the concubines, Karl fathered several other children (including Drogo von Metz and Hugo ), but they were not legitimate heirs.

Karl showed particular affection for his daughters. In a letter written in 791, he referred to her as dulcissimae filiae , his “sweetest daughters”. While the sons received military and political training and were far away from court at a young age (the sources also contain references to partly homoerotic relationships between Karl's son of the same name, Karl the Younger), his daughters received a very comprehensive education. Karl made sure that no one could gain a political advantage by marrying into the family, which is why he mainly kept his daughters at court. But he gave them considerable freedom in their conduct of life; in the sources the love affairs of the daughters are partly criticized. Bertha, for example, had an affair with Angilbert and had two sons, including the future historian Nithard . After Karl's death, his successor Ludwig, who was more strongly oriented towards church norms, put an end to this indulgence.

effect

middle age