Prince Abbey of Kempten

|

Territory in the Holy Roman Empire |

|

|---|---|

| Prince Abbey of Kempten | |

| coat of arms | |

|

|

| map | |

|

|

| Territory of the Princely Monastery of Kempten (map from 1802) | |

| Location in the Reichskreis | |

(Map by F. de Witt, 17th century) (Map by F. de Witt, 17th century)

|

|

| Alternative names | Kempten Abbey, Kempten Abbey, Kempten Imperial Abbey, Kempten Imperial Abbey |

| Arose from | Carolingian own monastery or ordinary abbey ; Imperial monastery; Imperial Abbey |

| Form of rule | Elective monarchy |

| Ruler / government | Prince abbot |

| Today's region / s | DE-BY |

| Parliament | Reichsfürstenrat : 1 virile vote |

| Reich register | 2 glaives (1422); 5 on horseback, 18 foot soldiers, 180 guilders (1521); 6 on horseback and 20 foot soldiers or 152 florins (1663); 6 on horseback and 20 foot soldiers or 152 guilders, 90 guilders for the Supreme Court (18th century) |

| Reichskreis | Swabian Empire |

| District council | County council: 10 on horseback, 36 foot soldiers (1532) |

| Capitals / residences | Kempten |

| Denomination / Religions | Roman Catholic |

| Language / n | German , Latin |

| surface | approx. 1000 km² = 18 square miles (1803) |

| Residents | 40,000 to 42,000 (1803) |

| Incorporated into |

Electorate of Bavaria

|

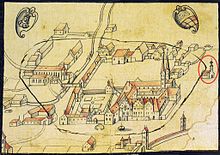

The Princely Monastery of Kempten (Latin Abbatia principalis Campidunensis ) was the historical territory of the former prince and exemte Benedictine Abbey Kempten in the Swabian Empire of the Holy Roman Empire . The sovereign was the respective prince abbot . The center of the prince abbey was the monastery ( prince abbot's residence ) and the collegiate church of St. Lorenz in Kempten (Allgäu) . In 1802 the prince monastery was occupied by troops from the Electorate of Churpfalz-Baiern and dissolved a year later in the course of secularization .

geography

In the area of today's Bavarian administrative district of Swabia , the prince monastery was the second largest area after the bishopric Augsburg with about 1000 km² . Until the abolition of the ecclesiastical principalities in the context of secularization in 1802/03, it included the district of Martinszell von Waltenhofen in the south , Legau in the north-west, Grönenbach in the north, Ronsberg in the north-east and Unterthingau in the east . In addition to the monastery town of Kempten as the residence of the prince abbot, nine markets, 85 villages and a few hundred hamlets and individual farms were part of the closed territory on both sides of the Iller . An enclave in stiftkemptischen area formed the imperial city of Kempten, an exclave of Prince pen was with laughter between Memmingen and Ottobeuren .

history

founding

The monastery, consecrated to Saints Mary and Gordian and Epimachus , was founded in 752 by Abbot Audogar .

The Carolingians , especially Queen Hildegard and her son Ludwig the Pious , supported the monastery sustainably, according to legends. In 773, an official founding act for the monastery was supposedly held by Hildegard. In 853 the Marca Campidonensis was confirmed as the area of disposal of the abbots . The extent of the mark almost coincided with the later county of Kempten. The monastery used a lot of effort to achieve a better rank as a Carolingian monastery at that time. This also included the forging of documents about the alleged involvement of Hildegard and Charlemagne in the founding of the monastery.

Rise to the imperial principality

Emperor Heinrich IV confirmed the imperial immediacy of the monastery in 1062 . The abbots from Kempten have held the title of prince since the 12th century. Early on, the monastery acquired a dominion in which, from 1213, it also had the count and bailiwick rights that had previously been exercised by the now extinct Margraves of Ronsberg . In 1218 Frederick II ceded the bailiwick to the abbot, who had to promise an annual payment of 50 silver marks and the waiver of the right to mint. Henry VII confirmed the transfer of the bailiwick to the monastery in 1224. Under Conrad IV , the bailiwick fell back into royal hands in an unknown manner, here the Staufer , but Konradin pledged it again to the monastery in 1262. Various attempts by King Rudolf I to call them in for the empire, and by Emperor Karl IV. To give them to Duke Friedrich III. von Teck was ended by repeated pledges to the monastery itself, finally in 1353.

Together with the regulations from 1220, the acquisition of a high bailiwick created a good basis for the management of the monastery to establish a sovereignty within the district of the county. This created the basis for Kempten to be the only royal monastery in East Swabia to become an imperial principality - a status that finally reached its climax in 1548 with the award of a virile vote at the Reichstag .

Power and territorial development in the 14th and 15th centuries

In the late Middle Ages , the area was expanded to include fiefs and serfdom . It was a view that was fixed on regional customary law, according to which tax sovereignty , compulsory courts and military sovereignty were not liable to the country, but to the individual's legal status. In the rest of Swabia, however, there were lower court rights over people in the manor . In addition to serfs, there were numerous independent farmers in the county of Kempten. They could put themselves under the protection and protection of a court lord or assume the status of a stake citizen of an imperial city and freely choose their master. Only a small part of the peasant property in the county was under the manorial rule of the monastery, many individual farms had a noble landlord or were free property of the peasants.

These reasons motivated the prince abbots to have a closed territory. The high jurisdiction of the County Court of Kempten was one way of making this possible. The abbots tried to demote the peasants living in the county borders to the status of serfs of the monastery. This humiliation generated anger and aggression on the part of the subjects, which escalated into a peasant uprising in 1491/1492. After the conflict subsided, the monastery took on its previous fiefdoms orders again, so that the aggression of the subjects intensified and finally culminated in the Great Peasants' War of 1525.

Peasants' War and Allgäu heaps

The Allgäu heap played an important role in the peasant war . The prince abbot Sebastian von Breitenstein , who hid from the peasants in the Abbey-Kemptischen Hauptburg Liebenthann in 1525 , was forced to leave his refuge by the siege; the peasants gave him free retreat. He sought asylum within the walls of the imperial city, which, however, forced him to sign a contract with which the monastery ceded the rights over the imperial city for 30,000 guilders. A year later, in 1526, Sebastian von Breitenstein acquired the Sulzberg rule for this amount.

The uprisings of the peasants against the prince abbot were put down with the help of the Swabian Federation , but the goal of the Federation was to restore peace in the prince monastery. The framework for this was formed by the Memmingen Treaty of 1525, through which tax levies and fees were fixed.

Destruction and rebuilding

The monastery and collegiate church were burned down by Swedish troops in the Thirty Years War in 1632. From 1651 onwards, the monastery was rebuilt as the first monumental baroque monastery complex in Germany. Prince Abbot Roman Giel von Gielsberg appointed the Auer master builder Michael Beer , who designed the abbot's residence and collegiate church in the baroque style. The foundation stone was laid on 16 April 1652, 1654 which came Graubündner builder Johann Serro Beers in succession. The shell was finished in 1656, the main building of the residence was completed in 1670 with the sacristy between the residence and the church. Work on the church towers stopped in 1673 without being completed.

On April 19, 1728, the settlement around the residence and the collegiate church of St. Lorenz by a diploma from Emperor Karl VI. raised to town. This meant for the pen city, although the city charter , but we gave up a bourgeois government.

secularization

With the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 25 February 1803, the monastery and prince monastery were dissolved. The secularization of the monastery, together with the mediatization of the imperial city of Kempten, enabled the first steps towards a merger of the two city structures developed next to each other, which then took place in 1818.

The former collegiate and parish church of St. Lorenz now serves as a pure parish church for the parish of St. Lorenz . The rooms of the residence are used by the public prosecutor's office and by the district and regional court. The state rooms of the residence can be visited as part of guided tours.

Cultural assets of the prince monastery after secularization

After the dissolution, 94 pictures from the princely collection came to Munich. The archive was transferred to the General Reich Archive. Part of the library went to Augsburg; many books remained in the monastery attic, the remains were later given to the Metten monastery . Part of the working library returned to the residence in 2010 as a gift from Paul Huber (1917–2010), the former owner of Kösel-Verlag . Today the rich archive holdings of the prince monastery are in the Augsburg State Archives ; its reconstruction by Gerhard Immler is considered an archival model case of the opening up of an official registry for an important territorial rule of the Old Empire. The differentiated administrative structure of the monastery association is taken up by historical research, also because of the development by the monastery archivist Pater Feigele in the 18th century.

Inner development

administration

Bailiffs and nursing offices

The administration of the large territory was initially carried out by provincial bailiffs in the respective districts.

Roman Giel von Gielsberg rearranged the territorial administration of the dominion in 1642 by abolishing the office of governor and setting up seven nursing offices and other central authorities. Although these were based on the previous bailiwicks, they were also responsible for the old monastery property in the respective catchment area:

- Nursing office on this side of the Iller with its seat in Kempten

- Hohenthann Nursing Office based in the Hohentann Castle of the same name , later in the village of Lautrach

- Falken nursing office based in the Falken Castle of the same name , later - extraterritorial - in the monastery town of Kempten

- Liebenthann nursing office based in the Liebenthann Castle of the same name , later in the Obergünzburg market

- Kemnat Nursing Office based in Kemnat Castle of the same name

- The Thingau Nursing Office, based in the Unterthingau market

- Sulzberg and Wolkenberg nursing office initially located at Wolkenberg Castle (today the Wildpoldsried community , in the village of Lenzfried since 1642 ) (the Wolkenberg lordship was acquired by the prince monastery in 1398)

Rupert von Bodman set up an eighth nursing office in 1695 with the acquisition of the rulers of Rothenstein and Grönenbach .

The nursing offices were divided into parishes and main teams, larger parishes each comprised several main teams.

Sovereign rights of third parties

In some areas the rights of the prince monastery overlapped with other rulers:

- In the Reichsvogtei Aitrang , the sovereignty was exercised by the prince monastery, but the monastery of St. Mang in Füssen owned the manor and the lower court.

- For Wollmuths ( Waltenhofen ) the owner was the rule Rauhenzell (St. Immenstadt ), they had the lower jurisdiction there.

- 180 families from Augsburg lived in the Unterthingau nursing office , while some Kemptic families lived in the episcopal nursing office in Markt Oberdorf .

- In the rule of Ronsberg the House of Austria exercised certain rights belonging to the state sovereignty.

- In Steinbach , the monastery exercised the highest jurisdiction and some regalia; it belonged to the Premonstratensian Monastery of Rot an der Rot.

From 1767, the feudal lordship of Binswangen formed a remote exclave .

Imperial city of Kempten as an enclave with princely rights

The history of the prince monastery was also determined by constant disputes with the neighboring imperial city of Kempten, which had been on the way to imperial freedom since a first privilege in 1289 and represented an enclave in the territory of the prince monastery. The contrasts intensified from 1527 when the city joined the Reformation . As early as 1525, under the mayor Gordian Seuter, the city had succeeded in buying all of the remaining rights and possessions in the city from Prince Abbot Sebastian von Breitenstein , the former lord of the city.

right

The Benedictine monastery was able to acquire bailiwick rights from the empire in the 13th and 14th centuries, finally in 1353. Although the abbot claimed an imperial prince from 1212 the title and rank, but received only this mid-14th century, the rights as imperial prelate .

The abbots and prince abbots exercised episcopal rights. They were therefore allowed to consecrate churches, for example . Disputes with the Bishop of Constance about the canonical position of the abbey, which began in 1382, were settled in 1483 by the papal exemption . The religious reforms of the 15th century did not affect the monastery.

economy

Until modern times, the economy of the prince monastery was that of a very agricultural country. From the second half of the 17th and 18th centuries, the prince abbots tried to strengthen the economy. The pronounced state economic control played a key role. The economic center was the monastery rebuilt after the Thirty Years War with the monastery settlement. The social life of the abbey town was shaped by the prince's court and the court officials. In addition to the employees of various ranks, professional life in the monastery city was shaped by craftsmen.

Craft

Important business operations were the brewery (see Altes Brauhaus and Stiftsmälzerei ) and the pen printing house. Both were operated independently by the monastery.

Guilds of the collegiate city also included masters from the surrounding villages. However, it was never possible to achieve such a variety as existed in the neighboring imperial city of Kempten.

The penal area included several markets, the oldest was built in 1407 and was called Obergünzburg . With its small-town character, this market made a significant contribution to economic life. Other markets in the monastery area were significantly weaker. They developed into centers from handicrafts and retail trade to local supply. Except for a higher proportion of tradespeople compared to normal villages, they hardly differed in terms of structure.

The usual rural crafts were butchers, millers, tailors, shoemakers, blacksmiths, weavers and stocking knitters.

Flax cultivation and processing was an important source of income . The climatic conditions were almost ideal. The rural weavers were a cheaper labor than the masters of the imperial city of Kempten, so that the prices could be kept low and thus competitive through the regulated economic planning. The weavers of the imperial city thus had a strong competitor and difficult competitive situations.

Agriculture

Agriculture played an enormous part as the basis of existence for the people. In animal husbandry, the focus was on raising cattle. The northern areas of the prince monastery were intended for arable and grain cultivation. The grain was stored centrally in the grain house .

The planned desertification was important for efficient agriculture . In this case, scattered properties were merged and assigned to one owner.

forestry

The economic importance of forestry for the prince monastery was only recognized in the 17th century. In the Kürnach and Eschach valleys , Prince Abbot Rupert von Bodman had glassworks built that consumed a lot of wood. This clearing made it possible for small farmers to settle. The brewery in Kempten also consumed a lot of wood.

Pond and fish management

With the fasting regulations , the fishing industry was given some importance. This has been intensively pursued since the Middle Ages. In modern times, various still waters ( Wagegger Weiher , Schwabelsberger Weiher , Bachtelweiher , Stadtweiher , Herrenwieser Weiher , Eschacher Weiher ) have been developed. These served at the same time through long-distance lines to supply the abbey city and the local industry with water.

coat of arms

The prince monastery had its own coat of arms. Probably the oldest surviving character came from the second half of the 14th century. It is divided into red and blue with a white wave head. This traditional coat of arms can still be seen in the middle of the 16th century on the court seals of Obergünzburg, Kimratshofen , Unterthingau and Legau .

In the abbey seals, under Abbot Friedrich von Laubenberg , the abbey coat of arms appeared next to his personal coat of arms: the split shield with the crowned bust of the founder Hildegard.

The upper coat of arms of the monastery may have originated in the second half of the 14th century and showed a boy dressed in black with a sword and abbot's staff growing on a helmet.

At a later time, the princely court chamber had a coat of arms divided into red and blue with the crowned bust of Hildegard in a white veil and black skirt with a yellow hem and five yellow baubles hanging on it. On the blasting helmet a growing boy in a black coat sprinkled with yellow baubles, who holds a sword on the right and a scepter on the left.

The basic colors blue and red remained an essential part of the coat of arms for many communities in the districts of Oberallgäu , Unterallgäu and Ostallgäu . Examples include Durach , Buchenberg and Aitrang .

The former district of Kempten (Allgäu) continued the abbey coat of arms almost true to the original.

Abbots and prince abbots of Kempten

The first abbot of Kempten was Audogar. Prince abbots are attested from the 12th century, the last being Castolus Reichlin von Meldegg .

literature

- Birgit Kata et al. (Ed.): More than 1000 years: The Kempten Abbey between founding and closing 752–1802 . Allgäu research on archeology and history, No. 1. Friedberg 2006.

- Wolfgang Petz: Kempten twice. History of a twin city. Vögel, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-89650-027-9 .

- Maximilian Walter: The Princely Monastery of Kempten in the Age of Mercantilism. Economic policy and real development (1648–1802 / 03) (= contributions to economic and social history, vol. 68). Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-515-06812-0 .

Web links

- Gerhard Immler: Kempten, prince abbey: territory and administration. In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria . January 20, 2010, accessed March 9, 2012 .

- Gerhard Immler: Kempten, prince abbey: political history (late Middle Ages). In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria . July 7, 2011, accessed March 9, 2012 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Wolfgang Petz: Twice Kempten. History of a Twin City (1694–1836) , 1st edition, Ernst Vögel Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-89650-027-9 , pp. 504–506.

- ^ Gerhard Immler : Kempten, Fürstabtei: Territorium und Verwaltung, in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- ↑ Friedrich Zollhoefer (ed.): In Eduard Zimmermann, Friedrich Zollhoefer: Kempter coat of arms and signs including the city and district of Kempten and the adjacent areas of the upper Allgäu. In: Heimatverein Kempten (Ed.): Allgäuer Geschichtsfreund. 1. Delivery, No. 60/61, Kempten 1960/1961, pp. 46-49.

Coordinates: 47 ° 43 ′ 42.1 ″ N , 10 ° 18 ′ 46.2 ″ E