Charles IV (HRR)

Charles IV (Czech: Karel IV .; * May 14, 1316 in Prague ; † November 29, 1378 ibid), born as Wenceslaus ( Václav in Czech ), was a Roman-German King (from 1346), King of Bohemia (from 1347 ), King of Italy (from 1355) and Holy Roman Emperor (from 1355). He came from the Luxembourg dynasty and is one of the most important emperors of the late Middle Ages as well as the most influential European rulers of that time.

Life

Youth and the way to royalty

Charles IV, baptized in the name of Wentscheslaw ( Wenzel , Václav ), was the son of John of Luxembourg (also known as John the Blind), King of Bohemia (1311–1346), and his wife, who came from both the Přemyslids and the Habsburgs Elisabeth , the second eldest daughter of King Wenceslaus II. Přemysl .

Both in the paternal line of his father, the house Limburg-Arlon , his maternal line, the house Namur , as well as under the Přemyslids he became the first bearer of the name Karl. The Luxembourgers had good contacts with the French court for a long time, so it was the French King Charles IV who gave him his company name Karl (with Charlemagne as patron). In Paris, Charles received a comprehensive education that was by no means a matter of course for the time (approx. 1323-30). Pierre Roger (later Pope Clement VI , 1342-52) was one of his tutors. In France, the marriage with Blanca Margarete von Valois (French Blanche de Valois) was founded.

In 1331 he went to Italy, where his father Johann had far-reaching plans. It was here that Karl carried out independent official acts for the first time, even if his father's plan to establish a Luxembourg rulership complex in northern Italy failed in 1333, mainly due to the opposition of some powerful Italian city-states and the Kingdom of Naples . The relationship between father and son was ambivalent. It was by no means free of tension, which is partly due to the argument between Karl's parents, but also to the different characters. Johann was considered a chivalrous and daring character, Karl, on the other hand, looked more thoughtful and (except in his youth) averse to the tournament. Karl later wrote an autobiography , which does not cover his entire life, but only his childhood and adolescence; In any case, it tells us that he spoke five languages (Latin, German, Bohemian , French and Italian). In 1333 Charles returned to Bohemia and in 1334 was enfeoffed with the Margraviate of Moravia . In the conflict with the influential barons and his father, he was largely able to assert himself. In 1335 he was involved in the conclusion of the treaty between the Kingdom of Bohemia with Poland and Hungary (it was about the claims to the throne of the Bohemian crown on the two kingdoms). 1335–38 he was also regent in Tyrol for his younger brother Johann Heinrich (* 1322) and his Görzerische wife Margarete (later called Maultasch ) . The Tyroleans had refused to be divided between the Habsburgs and Wittelsbach, and Karl had to occupy the country militarily against the Habsburgs.

In 1336/37 and 1344/45 he accompanied his father on trips to Prussia . On June 8, 1341 Johann transferred the administration of the kingdom to Karl due to his blindness; soon afterwards Johann effectively withdrew completely from the government.

During the same period, the conflict between Ludwig the Bavarian and his opponents in the empire came to a head. Pope Clement VI , Karl's former tutor at the French court, promoted the opposition, and so Karl, supported by his great-uncle Baldwin von Trier , one of the most important imperial politicians of the 14th century, was finally set up as an anti-king to Ludwig and on November 26, 1346 - “wrong Place ”- crowned king in Bonn's cathedral basilica. After receiving the license to practice medicine, which Karl had not asked for, he was elected again on June 17, 1349 in Frankfurt am Main and crowned again on July 25 in Aachen that same year . Before the coronation he had to wait a few days in front of the city because Aachen was full of pilgrims and / or flagellants . Because of the plague, they came to Aachen for an unscheduled visit to the shrine .

As early as August 1346, Karl's father Johann was killed in the Battle of Crécy , in which Karl also took part; However, Karl had withdrawn early and under circumstances that had not been clarified. On September 2, 1347, he succeeded his father as King of Bohemia. Then in the same year he undertook a homage trip from Prague to Bautzen , the capital of the Bohemian outlying region of Upper Lusatia , to be paid homage there by the Lusatian estates. Ludwig the Bavarian died soon after, so that an open conflict was prevented. Now Günther von Schwarzburg was raised to the rank of anti-king Charles (1349).

Charles's imperial policy until his death

Charles's first years of reign: securing rule, plague and pogroms against the Jews

Karl was able to quickly prevail against Günther von Schwarzburg. In May 1349, the weak rival king renounced his title in a treaty and died soon afterwards. After Karl had weakened his opponents through a marriage alliance with the Count Palatine near the Rhine and the false Woldemar (an allegedly surviving member of the Ascanian ruling family who put pressure on the Wittelsbachers in the Mark Brandenburg ), an understanding was reached with the Habsburgs in 1348 and 1350 with the Wittelsbachers (Treaty of Bautzen). Now Karl could consolidate his rule.

At the same time, the plague wave reached its peak. The epidemic, also known as the Black Death , depopulated entire regions, the population of which in some cases fell by more than a third. Since the desperate people were looking for the cause, the claim that the Jews had poisoned wells was often believed and now exploited. During the Jewish pogroms in Germany in 1349, the so-called plague pogroms , Karl was at least guilty of complicity: In order to pay off his debts, Karl pledged the royal Jewish shelves , including to Frankfurt am Main . It was even regulated what to do with the property of Jews, and impunity was assured if “the Jews were to be killed there next” (Frankfurt documents of June 23, 25, 27 and 28, 1349, referring to Nuremberg, Rothenburg ob der Tauber and Frankfurt am Main). Just a month later, such a pogrom occurred in Frankfurt. Although he was able to effectively protect the Jews in his territory of Bohemia and also elsewhere, e.g. B. in Ulm 1348/1349, at least made the (unsuccessful) attempt, this event raises many questions in relation to Karl's character, especially since Karl otherwise always endeavored to convey the image of a just Christian ruler. The toleration of the murders also violated the legal understanding of the time, since the Jews were under the direct protection of the king and made payments for it. It turned out that Karl often acted more expediently, with his behavior ensuring the loyalty of many cities that were involved in the pogroms against the Jews.

Charles's policy on Italy and France

In 1354 Karl, whose arrival Cola di Rienzo , who had stayed in Prague for some time, had repeatedly warned, moved to Italy with only a small army. He was crowned on January 6, 1355 in Milan with the iron crown of Lombardy. His coronation was in Rome on April 5, 1355 by one of Pope Innocent VI. who, like all popes since Clement V , resided in Avignon, was commissioned by a cardinal. A little later he left Italy again without having taken care of the order of the situation there, even though he was able to draw financial profit from the move to Rome through the payments of numerous municipalities and had at least achieved the imperial coronation without bloodshed. Nevertheless, his behavior towards the papacy contributed to the fact that he was referred to as "priest king" (rex clericorum), which is certainly wrong, but was characteristic of Karl's curial policy, which relied heavily on agreement with the pope.

Charles's first Italian train, like the second Italian train 1368-69 (in which he cooperated with Pope Urban V , from whom he hoped that the papacy would return from Avignon to Rome) had little significance. His Italian policy was by and large ineffective, because Charles was satisfied with the imperial crown. He withdrew funds from the communes and granted privileges for it, but otherwise did not interfere further in Italian affairs; for this his behavior was described as that of a merchant (see Matteo Villani and Petrarca ). With this, Karl gave up the universal policy of his grandfather Heinrich VII in favor of an imperial policy based on domestic power . However, he achieved recognition of his position as emperor through Florence and Milan and did not give up any imperial rights in Italy.

In the West, Charles did little to counteract the expansionary policy of the Kingdom of France there , with whose royal court he maintained good relations. On the contrary: despite his coronation in Arles in 1365, he released Avignon from the feudal rule of the empire and in 1378 abandoned the imperial vicariate in the Kingdom of Burgundy (Arelat), probably in order to be able to pursue his imperial policy undisturbed by external interference. Nevertheless, the advance of France was given a boost, even if in 1361 Geneva and Savoy were separated from the Kingdom of Burgundy and integrated directly into the Holy Roman Empire.

The Golden Bull and politics in Germany

In 1354 Charles's great uncle Baldwin of Luxembourg , who had proven to be the emperor's most important support in the west, died. Probably the most momentous step in Karl's government, the adoption of the Golden Bull in 1356, was only possible after difficult negotiations. The bull regulated, among other things, the electoral process of the Roman-German king and set the number and names of the electors . So it became the "Basic Law" of the Reich until its fall in 1806. The " Männleinlauf " at the Nuremberg Frauenkirche is still a reminder today.

In research, however, it is disputed whether Charles was able to record a success with this or whether it was not more of a success of the electors, who thereby put a stop to Karl's efforts to achieve a hegemonic monarchy . As history has shown, it could be used to their respective advantage by both the electors and the imperial government. What is remarkable about the Golden Bull is that it does not mention the need for papal confirmation, or approbation, in order to obtain imperial dignity. In addition, the papal imperial vicariate law was simply abolished in the law. Charles's eldest son, Wenceslaus , who had been King of Bohemia since 1363, was elected Roman-German King on June 10, 1376 while Charles was still alive. The Golden Bull did not provide for this, but did not prohibit it either, so that Karl was able to enforce the election of his son through a very clever policy, although he had to buy the votes of the other electors with large sums of money, which is generally a common method for Had been asserting his interests. Until the end of the Roman-German Empire in 1806, the dynastic succession of the Luxembourger and the Habsburgs related to them was only interrupted by the Wittelsbacher Ruprecht von der Pfalz (1400–1410) and Charles VII of Bavaria (1742–1745) while the elective monarchy continued .

In the north, Karl became aware of the Hanseatic League and in 1375 was the first Roman-German king since Friedrich I. to visit the city of Lübeck . In Tangermünde ( Altmark ), easily accessible from Bohemia on the Elbe, Karl set up his Brandenburg residence in the old imperial castle. The city was to become the capital of the central provinces, which was prevented by his death. Then there was a restless development in the Mark Brandenburg until the Hohenzollern took over the office of elector in 1415 and initially also resided in Tangermünde.

The imperial city of Nuremberg , with which the emperor worked closely ( Via Carolina , sponsorship of the burgraves from the house of Hohenzollern ) , also played an important role in Karl's politics . Karl u. a. the goal of creating an “imperial landscape” in this region (called New Bohemia ); The Nuremberg Imperial Castle and the Wenzel Castle in Lauf an der Pegnitz, built for him from 1356, served him as residences there . In the east, Karl pursued domestic power political goals with regard to Poland and Hungary (see below).

Karl died in the same year in which the occidental schism also occurred (1378). The emperor, who was personally pious and had always tried to rule in unison with the Pope, could do nothing more to prevent this schism, but decided in favor of the Roman Pope.

Charles as King of Bohemia

After Karl had ensured the elevation of the Prague diocese to an archdiocese in 1344 , he initiated the construction of the Gothic St. Vitus Cathedral (katedrála sv. Víta, Václava a Vojtěcha). He had the Karlštejn Castle built for the safe storage of royal and imperial regalia . The extensive construction activity in his residence made Prague the Golden City . The Charles Bridge over the Vltava is a testament to this . In 1348 Karl founded the first university in Eastern Central Europe , the Charles University (Univerzita Karlova), based on the model of the University of Naples established by Emperor Friedrich II and that of the Studium generale at the Paris "universitas". He developed Prague into one of the most important intellectual and cultural centers of its time and became the de facto capital and residence of the Holy Roman Empire ( Praga Caput Regni : Prague capital of the empire is an inscription on the Old Town Hall); Frankfurt am Main, Nuremberg and from 1355 Sulzbach (today Sulzbach-Rosenberg ) as the center of the imperial new acquisitions in today's Upper Palatinate continued to be of importance . The imperial chancellery led by Johannes von Neumarkt was exemplary for the training of the New High German language . The Prague School of Painting brought late Gothic panel painting to its peak.

However, Charles failed with his land peace ( Maiestas Carolina ) in 1355 due to the resistance of the local nobility. During his reign, Silesia was finally incorporated into the Bohemian rulership with the Treaty of Namslau in 1348, for which his father had created the conditions with the Treaty of Trenčín . In return, the Polish king Casimir the Great received Mazovia as a personal fief. Charles's marriage to Elisabeth, a granddaughter of Kasimir, in 1363 was supposed to settle the old Bohemian-Polish conflict for the time being.

Further information on this topic: → History of Prague

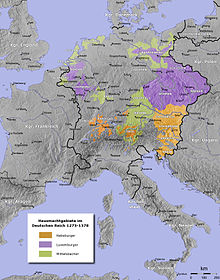

Charles's power policy

Karl was without a doubt the most successful domestic power politician of the late Middle Ages . The Bohemian sovereignty over Silesia (finally 1368) and Lower Lusatia (purchase in 1367) was also secured. In 1373 he received full power of disposal over the Mark Brandenburg in the Treaty of Fürstenwalde and thus a second electoral dignity for his house; In addition, the mark was recorded statistically as precisely as possible in the so-called land book in order to be able to collect taxes more efficiently. The marriage of his son Sigismund to the heiress of King Ludwig I of Hungary (betrothal in 1372) also secured this kingdom for the Luxembourgers. However, the hoped-for acquisition of Poland did not succeed. In order to strengthen his house power, Karl did not shy away from pledging imperial property or even giving up imperial rights, as in the west of Burgundy (see above).

Charles's pledge policy was partly due to his chronic lack of money (he had to raise an enormous sum just to secure his election as Roman-German king), and partly to his dynastic policy. From now on, every subsequent king was dependent on his household power. The House of Luxembourg was now almost invulnerable. But this turned out to be a heavy burden for his son Sigismund, as he had no significant household power and no major imperial estates outside of Luxembourg's sphere of influence. Karl also determined that after his death his sons and relatives should be taken care of from the house power complex, which ultimately meant that the position of power created by Karl was lost again.

End of life

After the emperor's death on November 29, 1378, his body was laid out for eleven days in the auditorium of Prague Castle . The funeral ceremonies that followed lasted four days, during which the deceased, accompanied by 7,000 participants, was transferred from the castle through Prague's Old and New Towns and then over the Charles Bridge to Vyšehrad . There he was laid out for one night. For two more days the remains were made accessible to the public in the convent of St. Jacob and in the St. John's Church of the Virgin Mary. The concluding burial ceremony in St. Vitus Cathedral in the presence of his entire court was celebrated by Prague Archbishop Johann Očko von Wlašim , assisted by seven other bishops.

Chronology of the title

- First election as Roman-German King ( Gegenkönig ) in Rhens on July 11, 1346, coronation on November 26, 1346 in Bonn

- From September 2, 1347, King of Bohemia as Charles I.

- Second election as Roman king on June 17, 1349 in Frankfurt am Main, coronation on July 25, 1349 in Aachen

- From January 6, 1355 titular king of Italy

- From April 5, 1355, Roman-German Emperor as Charles IV.

- From June 4th 1365 King of Burgundy

Marriages and offspring

First marriage: Charles IV married Blanca Margarete von Valois in 1329 .

Second marriage: Charles IV married Anna von der Pfalz in 1349 .

- Wenceslas (1350-1351)

Third marriage: Charles IV married Anna von Schweidnitz in 1353 .

- Elisabeth of Luxembourg-Bohemia (1358–1373) ⚭ 1366 Albrecht III. , Duke of Austria

- Wenceslas IV (1361–1419), King of Bohemia

- ⚭ 1370 Johanna of Bavaria

- ⚭ 1389 Sophie of Bavaria

Fourth marriage: Charles IV married Elisabeth of Pomerania in 1363 .

- Anne (1366–1394) ⚭ 1382 Richard II , King of England.

- Sigismund (1368–1437), Holy Roman Emperor

- ⚭ 1385 Mary of Hungary

- ⚭ 1408 Barbara von Cilli

- Johann (1370–1396), Duke of Görlitz, Margrave of Brandenburg ⚭ 1388 Richardis of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

- Karl (1372-1373)

- Margarete (1373–1410) ⚭ 1387 Johann III. , Burgrave of Nuremberg

- Heinrich (1377-1378)

ancestors

Karl as a writer

Vita Caroli Quarti

Charles IV's autobiography is the first self-portrayal of a medieval German ruler and covers the period from his birth (1316) to the election of a king (1346). While the first 14 chapters are strictly subjective and tell the story continuously until 1340, the last 6 chapters remain objectively distant, so it is assumed that another author from the ruler's circle is responsible. The autobiography is not uniform, but also includes other literary genres, e.g. B. a treatise on life and domination or an exegesis of scriptures for the feast of St. Ludmilla . The main focus of the presentation, however, is the moments in the life of Charles IV, in which he proved himself against great opposition. B. when he was the only one who survived the poisoning of his followers by the grace of God, as he writes (chap. 4). Another interesting anecdote is the story of a ghostly apparition during an overnight stay in Prague Castle (Chapter 7). Chapter 7 also contains a vision of Charles: An angel kidnaps him at night and takes him to a battlefield, where another angel cuts off the genitals of the leader of the attackers, the Dauphin of Vienne, because he has sinned against the Lord. The vision follows the classic structure of medieval visions, and the punishment of the Dauphin is also a medieval topos. The Dauphin Guigo VIII actually died on July 28, 1333 of the consequences of a wound inflicted on him during the siege of La Perrière Castle.

Wenceslas legend

The cult of St. Wenceslas played a central role in Charles' life. He himself was named after the Bohemian national saint until he was seven years old and had his firstborn baptized in this name. Charles' writing is considered the high point of the Wenceslas worship. He wrote it between 1355 and 1361, possibly 1358 as a votive offering for the birth of his daughter Elisabeth. Like every fully developed medieval legend of saints, the legend of Charles Wenceslas consists of a life story and a miracle story (following the translation of the saint's corpse to his place of worship, the Prague Cathedral). Charles IV processed the surviving lives of the saint probably from the 10th century. So it is a compilation of earlier texts. Charles IV felt obliged to the Catholic Liturgia Horarum. Even today, the Liturgy of the Hours is binding for the clergy of the Catholic Church. The purpose of the Liturgy of the Hours is to bring each time of day with its particularity before God. Charles IV performed the Divine Office like a clergyman, since by virtue of his coronation he also felt himself to be a deacon. During the Christmas service he therefore exercised the right to sing the Christmas Gospel in front of the clergy and the people in full imperial regalia. He underscored his readiness to defend the gospel by swinging the kingdom sword three times. So it is not surprising that the individual parts of the Wenceslas legend consist of lessons from a rhyme office. A classic passage can be seen in Lectio V: the so-called footstep miracle. According to this, St. Wenceslas is said to have visited the churches in the area in the company of his servant on a winter night. The saint walked barefoot through the snow, causing his feet to bleed and leave marks. The servant followed the trail of the saint and felt no more cold. This miracle is best known in the English-speaking world through the Christmas carol Good King Wenceslas .

Morality

A collection of philosophical sentences, spiritual texts and reflections on various religious and moral issues. The morals are evidence of Karl's deep faith and his conception of the virtue of a king: a king has to ensure justice and well-being of his country within the grace of God (chap. 1). Karl is explicitly named as the author in three headings. An example of Bible exegesis, from the sixth chapter, in which Charles IV is named as the author ("Haec est moralisatio domini Caroli regis Romanorum"). In this chapter Charles IV refers to a passage in Genesis (Gen. IV, 22) about "Thubalcain, who forged the tools of all ore and iron craftsmen". In the emperor's moralization, Thubalcain is equated with man: According to Karl, man has the task of acting like him: Namely, just as Thubalcain coaxed notes out of iron, so man should "cast" himself "notes" through mortification ( castigatio ) elicit and thus achieve perfection.

Prince mirror

The authorship of Charles IV, represented by the editor S. Steinherz, is no longer accepted in research today (see Prince's Mirror of Charles IV ). In the Fürstenspiegel, an unspecified emperor describes the correct way of governing for his son. The author draws mainly from Augustine and Petrarch.

reception

In modern research, Charles IV is judged differently. Representatives of a positive view are u. a. Ferdinand Seibt and Peter Moraw , partly also Jörg K. Hoensch . Sometimes very critical, but also very differentiated Heinz Thomas looks at him .

It is undisputed that Karl was highly intelligent and an excellent diplomat and that he promoted the arts and sciences. In the context of positive appreciations (for example by Moraw) he is referred to as the greatest Roman-German emperor of the late Middle Ages .

He is also credited with the fact that he did not get involved in Italian conditions like his grandfather Henry VII and that he was able to achieve the imperial title without bloodshed and in agreement with the Pope. His reign is seen as the last high point of the old empire in the Middle Ages, even if his empire hardly resembled the universal empire of bygone times.

On the other hand, it is critically noted that he was not ready to settle the political situation on the ground in Italy. His Italian move, on which he immediately headed north after the coronation, was viewed very critically by his contemporaries Petrarch and Matteo Villani . It is also pointed out that he did not succeed in maintaining the position of power that had been created. Moraw also admits that he left the base of the dynasty in Bohemia fragile. The policy of pledging is also negatively credited to him , as a result of which the empire developed into a pure power kingship . The fact that he partially failed to fulfill his duty to protect the Jews also weighs on the negative side of his government balance sheet.

The yardstick for the scientific and public interest in medieval rulers has been large-scale exhibition projects since the Staufer Show in 1977. The 600th anniversary of the death of Charles IV in the following year brought with it three such exhibitions. Competitive project to "Emperor Karl IV. 1316-1378" with approx. 200,000 visitors to the Nuremberg Imperial Castle is evaluated. The exhibition “The Parler and the Beautiful Style 1350–1400” (approx. 300,000 visitors), which opened in Cologne at the end of the year, with its three-volume catalog provided a foundation for “Art and Culture among the Luxembourgers”. A comprehensive re-presentation of these aspects offered “ Charles IV. Emperor by God's grace ”2006 in New York (Metropolitan Museum) and Prague (Burg), whereby the driving force was not understood as much as the Parler family of architects, but rather at court culture and the will to represent the House of Luxembourg. The first Bavarian-Czech state exhibition for the 700th anniversary of the birth of Charles IV in 2016 in the Wallenstein Riding School and Charles University in Prague as well as the Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg is linked to the consciously European perspective of this show, both in terms of organization and content . and cultural-historical objects presents the biography of the ruler in the context of an epoch described as a crisis.

Statues and monuments

- c. 1350, statues of Charles IV and Blanche von Valois, Duke Rudolph IV of Habsburg on the south tower of St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna .

- 1851, colossal statue for Prague , executed by Jacob Daniel Burgschmiet .

- 1899, Monument in Siegesallee in Berlin , Monument Group 13 , executed by Ludwig Cauer .

- 1900, bronze statue for Tangermünde , executed by Ludwig Cauer , gift from Kaiser Wilhelm II to the city.

literature

- alphabetically ascending

- Evamaria Engel (Ed.): Karl IV. - Politics and Ideology in the 14th century. Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 1982, DNB 830490582 .

- Jiří Fajt, Markus Hörsch, Andrea Langer: Exhibition catalog Charles IV., Emperor by God's grace. Art and Representation among the Luxembourgers 1347–1437, Prager Burg, February 15 - May 21, 2006. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-422-06598-7 (comprehensive new representation with numerous illustrations on art and culture of the Luxembourg house).

- Jiří Fajt, Markus Hörsch (ed.): Emperor Karl IV. 1316-2016. Exhibition catalog First Bavarian-Czech national exhibition (National Gallery Prague and Germanic National Museum Nuremberg). Národní galerie v Praze, Prague 2016, ISBN 978-80-7035-613-5 .

- Stephan Haering : KARL IV .. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 3, Bautz, Herzberg 1992, ISBN 3-88309-035-2 , Sp. 1136-1140.

- Marie-Luise Heckmann : Deputy, co-ruler and substitute ruler. Regents, governors-general, electors and imperial vicars in Regnum and Imperium from the 13th to the 15th century (= studies on the Luxembourgers and their time , volume 9), volume 2. Fahlbusch, Warendorf 2002, pp. 511–684, ISBN 3- 925522-21-2 .

- Marie-Luise Heckmann: Real-time awareness and international appeal. The Golden Bull of Charles IV in the late Middle Ages with a view of the early modern era . With an appendix with the collaboration of Mathias Lawo: Copies of the Golden Bull, arranged according to traditional configurations. In: Ulrike Hohensee , Mathias Lawo , Michael Lindner , Michael Menzel and Olaf B. Rader (eds.): The Golden Bull. Politics, perception, reception. Volume 1 . 2 volumes, Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-05-004292-3 , pp. 933-1042.

- Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller : Cogor adversum te. Three studies on the literary-theological profile of Charles IV and his office (= studies on the Luxembourgers and their time , volume 7). Fahlbusch, Warendorf 1999, ISBN 3-925522-18-2 .

- Christian Hesse : Synthesis and Awakening (1346–1410). (= Gebhardt: Handbook of German History. Volume 7b). 10th, completely revised edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-608-60072-8 .

- Eugen Hillenbrand : Karl IV . In: The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . Volume 4 . 2nd, completely revised edition. Berlin / New York 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-022248-7 , Sp. 995 ff.

- Jörg K. Hoensch : The Luxembourgers. A late medieval dynasty of pan-European importance 1308–1437 (= Kohlhammer-Urban pocket books. Volume 407). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-17-015159-2 , pp. 105-192.

- Klaus-Frédéric Johannes : Comments on the Golden Bull of Emperor Charles IV and the practice of electing a king 1356–1410. In: FS Jürgen Keddigkeit, 2012, pp. 105–120.

- Klaus-Frédéric Johannes: The golden bull and the practice of the king's election 1356-1410. In: Archives for Medieval Philosophy and Culture . Vol. 14 (2008) pp. 179-199.

- Martin Kintzinger : Karl IV. In: Bernd Schneidmüller , Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): The German rulers of the Middle Ages. Historical portraits from Heinrich I to Maximilian I. Unchanged reprint of the 2nd edition. Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-406-72804-4 , pp. 408-432 and pp. 593 f.

- Uwe Ludwig: Karl IV. And Venice: the Luxembourgers, the Markus Republic and the Reich in the 14th century , 1996, DNB 956486711 (Habilitation University of Duisburg 1996).

- Dietmar Lutz (Ed.): The Golden Bull of 1356, the most distinguished constitutional law of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, 650 years after it was passed at the Reichstag in Nuremberg and Metz , Schmidt-Römhild, Lübeck 2006, ISBN 978-3-7950- 7034-2 .

- Hans Patze (ed.): Kaiser Karl IV. 1316-1378. Research on emperors and empires (= sheets for German national history. Volume 114). Schmidt, Neustadt an der Aisch 1978, DNB 780478134 .

- Ferdinand Seibt : Karl IV. An emperor in Europe. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 978-3-596-16005-1 (reprint of the 1978 edition).

- Ferdinand Seibt (Ed.): Emperor Karl IV. Statesman and patron . Catalog of the exhibition in Nuremberg and Cologne 1978/79, Prestel, Munich 1978, ISBN 3-7913-0435-6 (catalog for the exhibition with essays by well-known historians).

- Ferdinand Seibt: Karl IV (baptismal name Wenzel). In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 11, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-428-00192-3 , pp. 188-191 ( digitized version ).

- Jiří Spěváček: Charles IV. His life and statesmanship . Union, Berlin 1979, DNB 790357070 (translated by Alfred Dressler).

- Heinz Stoob : Charles IV and his time. Styria, Graz a. a. 1990, ISBN 3-222-11942-2 (comprehensive biographical presentation).

- Heinz Thomas : Between Regnum and Imperium. The principalities of Bar and Lorraine at the time of Emperor Charles IV. Ludwig Röhrscheid Verlag, Bonn 1973.

- Heinz Thomas: German history of the late Middle Ages. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1983, especially p. 212 ff. (Good representation of the political history of the German late Middle Ages).

Web links

- Literature by and about Charles IV in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Charles IV in the German Digital Library

- Entry in the Residences Commission

- Regesta Imperii

- Publications on Charles IV in the Opac of the Regesta Imperii

- Constitutiones et acta publica imperatorum et regum 1357–1378 , digital advance publication of Charles IV's documents by the MGH

- Carolus IV in the repertory "Historical Sources of the German Middle Ages"

- Eva Schlotheuber : Petrarch at the court of Charles IV and the role of the humanists. In: Collective publication of the lecture series of the summer semester 2004 at the LMU Munich ( digitized version )

- Heiner Wember : May 14th, 1316 - birthday of Emperor Karl IV. WDR ZeitZeichen (podcast).

Remarks

- ↑ František Kavka: Chapter 3: Politics and culture under Charles IV . In: Mikuláš Teich (Ed.): Bohemia in History . Cambridge University Press , 1998, ISBN 0-521-43155-7 , p. 60.

- ^ Werner Paravicini : The Prussian journeys of the European nobility . Part 1 (= supplements of the Francia . Volume 17/1 ). Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1989, ISBN 3-7995-7317-8 , pp. 147 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Historical Association Ingelheim e. V. of August 3, 2010. (No longer available online.) Ingelheimergeschichte.de, archived from the original on January 20, 2009 ; Retrieved January 7, 2011 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Bernhard J. Huber, Hans R. Mackenstein: The male running at the Frauenkirche in Nuremberg and its history. In: Annual journal of the German Chronometry Society. Volume 44, 2005, pp. 127-160.

- ↑ Diether Krywalski: History of the German-language literature of the Middle Ages in the Bohemian countries . (= Contributions to German-Moravian literature ) Volume 11, Olomouc 2009, p. 232

- ↑ Milada Řihová: Classes at the Prague Medical Faculty in the Middle Ages. In: Würzburger medical history reports 17, 1998, pp. 163–173; here: p. 163.

- ↑ Memory of the Land

- ^ The autobiography of Charles IV = Vita Caroli Quarti. Introduction, translation and commentary by Eugen Hillenbrand, edited by Wolfgang F. Stammler, Alcorde Verlag, Essen 2016, ISBN 978-3-939973-66-9 .

- ↑ Eva Schlotheuber : The wise king. Concept of rule and mediation strategies of Emperor Charles IV († 1378). In: Hémecht. Journal for Luxembourg History # 63 (2011), pp. 265–279 ( digitized version ; PDF, 1.6 MB).

- ↑ René Küpper: Cat.-No. 19.9 a – c “Renaissance of Charles IV through three exhibitions in 1978”, pp. 619f. In: Exhibition cat. Prague / Nuremberg 2016.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Ludwig IV. |

Roman-German king from 1355 Emperor 1346–1378 |

Wenceslaus |

| Johann |

King of Bohemia 1347-1378 |

Wenceslas IV |

| Johann |

Margrave of Moravia 1333–1349 |

Johann Heinrich |

| Johann I. |

Count of Luxembourg 1346-1353 |

Wenceslaus I. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Charles IV |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Charles I of Bohemia |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Holy Roman Emperor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 14, 1316 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Prague |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 29, 1378 |

| Place of death | Prague |