John of Bohemia

Johann von Luxemburg ( Czech Jan Lucemburský , Polish Jan Luksemburski , French Jean de Luxembourg or Jean l'Aveugle and Luxemburgish Jang de Blannen ; * August 10, 1296 in Luxemburg , † August 26, 1346 in Crécy ), German also Johann von Böhmen , later called John the Blind , was King of Bohemia 1311–1346, Margrave of Moravia , Count of Luxembourg and Titular Kingof Poland 1311-1335. He was considered to be the embodiment of the knight ideal of his time, was a famous tournament hero and was also able to achieve some success in increasing his domestic power .

Life

Youth and the first years in Bohemia

Johann was the son of Emperor Henry VII and Margaret of Brabant . From a young age he accompanied his father and spent some time in Paris , where he also studied. After Henry VII was elected Roman-German king in 1308 , he initially enfeoffed Johann with the county of Luxembourg . In 1309 a Bohemian aristocratic party, which opposed the then Bohemian King Heinrich of Carinthia , made contact with Henry VII. Henry VII reacted by conducting negotiations with the Bohemian opposition circles from the beginning of 1310 and enfeoffing 14-year-old Johann with the Kingdom of Bohemia on August 30, 1310. Later that same day, Johann was married to the Bohemian Princess Elisabeth , a sister of Wenceslaus III, in Speyer . , with whose murder in 1306 shortly before the old ruling house of the Přemyslids had died out in the male line.

In October 1310 Johann moved to Bohemia with a contingent of troops, while his father Heinrich set out for Italy to obtain the imperial crown there. Two francs are set aside for the minor. Berthold Graf zu Henneberg, his tutor, and Archbishop Peter von Mainz received the power of attorney on October 16, 1310 to arrange the things of the Kingdom of Bohemia according to their well-being . Both are called excellent confidants. Johann, who had also been appointed imperial vicar by Heinrich , besieged the richest city of Kuttenberg at the time , but did not succeed in conquering it. So he turned to the small town of Kolín and was defeated again by Heinrich of Carinthia. When Johann finally marched into Prague , where he was crowned on February 7, 1311, he had not yet conquered anything. In his electoral capitals, he had to admit to the local nobility that offices could only be filled with Bohemians and Moravians. This expressed the increase in power of the nobility and the development of a Bohemian national feeling. For John, accepting the Bohemian crown also meant that he was claiming the thrones of Poland and Hungary held by the last two Přemyslids .

1313 was a bad year for Johann. Henry VII 's fatherly company , the Italian campaign, became a family tragedy: both his father, his mother and one of his father's brothers (Walram) were killed during the Italian campaign. Three years after Speyer's children's wedding, the Luxemburg house almost went out. Baldwin of Luxembourg , Archbishop of Trier, was now the senior of the House of Luxembourg. Johann was 17 years old and the father of a daughter. He tried in vain to succeed his father as the Roman-German king. He did not succeed in getting the German electors on his side, mainly because the electors feared for the balance of power and preferred to choose a weaker candidate. The choice finally fell on Ludwig from Wittelsbach in 1314 and Johann had to submit. In response to social pressure, the king dismissed Archbishop Peter von Mainz, Berthold von Henneberg and Ulrich Landgrave von Leuchtenburg from his service. From then on, the Luxembourgers and the Wittelsbachers stood together against the Habsburg Frederick the Fair , who had been elected by part of the electors. It became noticeable that some votes (such as those of Saxony) were controversial.

In the meantime, Johann, “King Stranger” in Bohemia, was forced to give the Bohemian aristocracy a greater share in power ( inauguration diplomas ), which ultimately ended in a civil war. To mitigate this, appointed Johann the Mainz Archbishop Peter von Aspelt the captain general of Bohemia. In 1317 the high nobility threatened not only with constant war, but also with the election of a Habsburg.

European politics

In an alliance with the Wittelsbachers, Johann fought in 1322 in the Battle of Mühldorf , in which the Wittelsbach-Luxembourg alliance was victorious. Johann received the Eger Reich pledge for this . Soon afterwards, however, there was a significant cooling of the relationship between Johann and Ludwig. In the dispute between Ludwig and the Pope, Johann wanted to convey what he hoped for Upper Italy as a rulership and the division of rulership, but these plans no longer came to fruition.

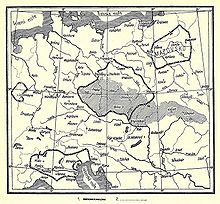

Johann could never really develop his power in Bohemia, since he was hardly in the country and intervened in several European conflicts. So he tried again and again to enforce his claim to Poland by intervening in the conflict between the Teutonic Order and the Polish King Władysław I. Ellenlang on the side of the order and participating in campaigns of the order in 1328/29, 1336/37 and 1344/45 against Lithuania . He was able to record certain successes in Silesia , where between 1327 and 1335 several dukes swore allegiance to Johann. In return, the Polish and Hungarian kings allied, both of whom felt threatened by John's claim to the throne.

Johann turned to France again after the traditionally good relations between the House of Luxembourg and the French royal house of the Capetians had suffered in previous years: Emperor Henry VII had braced himself against the French policy of expansion in the western border area of the empire; The French King Philip IV had also acted against the Emperor during Henry's trip to Rome . Now, however, the relationships normalized and Johann often spent several weeks a year at the Paris court, where the tournament system was cultivated. Philip VI, who came to the throne . even supported Johann with troops.

Finally, in 1335, the Polish King Casimir III tried . to settle the conflict with Johann. The kings met in Visegrád . Casimir recognized the Bohemian sovereignty over Silesia and waived the claims of the Bohemian crown in exchange for a cash payment. Johann gave up his claims to the Polish crown and limited support for the Teutonic Order.

Johann's Italian policy

King Johann and Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian met each other in 1330. Ludwig had long since been excommunicated by the Pope , but nevertheless led an Italian campaign. Johann, on the other hand, with wise restraint between Pope and Emperor, had become a powerful sovereign in recent years and acted skillfully in terms of real politics. He had become something like the arbiter and justice of the peace of Europe. Johann held the position of the German king until he returned home from Italy without luck. Johann seemed to be at the height of his success and so he came up with a new plan: He wanted to set off for Northern Italy himself. In fact, such a move to Italy was quite unusual in the context of a domestic power policy: Johann planned to set up a Luxembourg rulership complex in northern Italy.

Johann moved from Innsbruck to Trento in 1330 with only a small army of 400 armored riders . The reasons for moving to Italy are controversial in research; perhaps he wanted to protect the rights of the empire and respond to the request of the ambassadors from Brescia . They asked him to rule over their city: Mastino II. Della Scala , Lord of Verona , threatened them. Maybe Johann was just acting out of a thirst for adventure. Most likely, however, the establishment of a new power base in northern Italy was likely, whereby he could refer to his father Henry VII, who had also come to Italy to restore order in the war-torn country. It was precisely the city of Brescia, which once opposed his father to death and defeat, that opened its gates to Johann von Luxemburg. Within three months, all the major cities in Lombardy submitted to his patronage. This rule was against Philip VI. To defend.

In the Easter days of 1331, his son and heir to the throne, Karl, who was born in 1316, came to his side. He soon learned to contradict his father, but also to act independently. It was he who, as Crown Prince, at the age of 17, without consulting his father, ordered war against Florence - albeit with little success. Johann, on the other hand, received the signory over several cities and even the powerful Visconti recognized his formal sovereignty, but at the same time the distrust of Ludwig grew, who instructed his Italian confidants to obey only his imperial vicar Otto of Austria .

The last few years - between France and the Empire

Johann turned to the problems in the west. In 1332 he signed a treaty with the French king . In it, Johann pledged to provide assistance in the event of war (unless the Roman-German king was involved in the conflict). With this, Johann tied himself to the French court, but he probably hoped that this would result in a smoother domestic power policy, especially since the French were now supporting Johann in northern Italy with a contingent.

Several powerful cities and the King of Naples had formed an alliance there. Johann suffered several defeats and had to withdraw in October 1333 because his son Karl refused to defend the few remaining bases. The Italian policy of Johann had failed, but his appearance south of the Alps at least ensured that Northern Italy did not break away from the Empire - which would have been in line with the Pope's plans.

In 1335 Johann waived the Polish crown in exchange for financial compensation and those Silesian duchies , which had since become feudal dependent on Bohemia. At the same time, growing tensions between Johann and Ludwig were released. The emperor laid claim to the Alpine countries, which Johann claimed for himself due to the (albeit incomplete) marriage of his second son Johann Heinrichs to Margarete von Tirol . Fighting broke out in 1336, but a peaceful settlement was reached that same year. Shortly afterwards Johann embarked on a crusade against the Lithuanians.

Johann von Luxemburg, the great rider and tournament hero, was blind in his right eye in 1337. This ophthalmia was a hereditary disease of the Luxembourgers, only removing the diseased eye can prevent it from spreading to the healthy eye. Despite an operation by Guy de Chauliac , he also lost his left eye three years later and was henceforth called the blind man . During the fighting that soon broke out between England and France (see Hundred Years War ), Johann was on France's side, but Ludwig was on England's side. Johann even exercised command in Gascony in 1339 - and with success. Because of this, he was not present at the so-called Kurverein von Rhense , where the electors emphasized their claim to the election of the Roman-German king and rejected papal claims.

Tensions between the Luxemburgers and Ludwig persisted, and the opposition also grew in the Reich. On July 13, 1346, Karl, Johann's eldest son, who had shown more and more initiative and thus often contradicted his father, was elected the new Roman-German king - he was to rule the empire unchallenged soon after Ludwig's death and develop into a capable emperor, whose massive marriage and house policy in the empire, especially in northern Germany, which is far from the king, brought in a lot of opposition and resentment.

Johann fell in the battle of Crécy in 1346 , during which his son Karl withdrew from the battlefield under unexplained circumstances. According to tradition, the completely blind Johann is said to have been ridden practically defenseless into the fray and killed. Legend has it that after the battle, the then 16-year-old Prince of Wales , Edward of Woodstock (also known to posterity as the "Black Prince") approached the corpse. With the admiring words "There lies the Prince of Chivalry, but he does not die" ("Here lies the prince of chivalry, but he does not die") he is supposed to take Johann's Zimier , which consisted of two wings, among other things and made it his own. However, this episode is not historically secure. The ornament in the form of three ostrich feathers - which could, however, also have other origins - and Johann's German motto Ich Dien can still be found in the Prince of Wales's coat of arms (" badge ") to this day .

The death of the king made a deep impression on the European nobility: Johann remained true to his oath of alliance until the end and died as the embodiment of the ideals of European chivalry. The English remembered the dead king in a special funeral ceremony presided over by the Bishop of Durham . Incidentally, Johann's political work is usually judged more benevolently by modern research than was the case in the past, when he was mostly seen in the shadow of his politically more successful son and portrayed as an intolerant father who did not recognize the qualities of Karl.

Johann was first buried in the Luxembourg Altmünster monastery. After the destruction of the Benedictine abbey in 1543, Johann was buried in the Luxemburg monastery of Neumünster . During the turmoil of the French Revolution, Johann's bones came into the possession of the Boch industrial family in Mettlach an der Saar. According to the Boch family, Johann's bones rested there in an attic room. Pierre-Joseph Boch is said to have received the remains from monks to hide them from French revolutionary troops. His son Jean-François Boch donated the remains of Johann to the Prussian Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm in 1833 during his journey through the Prussian Rhineland. The Crown Prince, who saw Johann as an ancestor, commissioned the master builder Karl Friedrich Schinkel to design a burial chapel for Johann the Blind. From 1834 to 1835, Schinkel built the chapel in Kastel-Staadt in place of the old hermitage Klause Kastel on a rock above the Saar valley. On the anniversary of Johann's death in 1838, his bones were buried there in a black marble sarcophagus. The burial in the Klausenkapelle in 1838 is entered in the parish death register for 1838 on page 202.

“On August 26th, it was extremely lively in the romantic surroundings of the village of Castel an der Saar, an hour and a half from the district town of Saarburg. One expected the earthly remains of King John of Bohemia, which had previously found a place and asylum with the factory owner Boch-Buschmann in Mettlach and now in the municipality of Sr. Königigl. The Highness of the Crown Prince was cleverly transformed into a chapel, the former Roman camp, near Kastel, was to be solemnly buried. It was chosen on the day on which King John died almost 500 years ago (in 1346) in the battle of Crecy . […] In the middle of the chapel you can see a marble sarcophagus on which there is a bronze plate in which a biographical sketch of the life of King John of Bohemia is carved in Latin . Arrived at this point, Mr. Boch-Buschmann gave the district president von Ladenberg the key to the coffin in which the royal remains had hitherto been; whereupon such, after the coffin was opened, were recognized as far as possible by Mr. Boch-Buschmann and Count von Villers, who had seen them several times before. The coffin was then locked, and after the sarcophagus had previously been consecrated in the usual place, placed in it under the prescribed ceremonies, whereupon the blessing of the royal corpse and the closing of the sarcophagus took place. "

As part of a military state act (Ordre général No 5 of August 20, 1946 and Ordre général No 6 of August 22, 1946 of the Luxembourg Army), the Luxembourg national hero was on August 25, 1946 by Kastell (today Kastel-Staadt / District of Trier- Saarburg) with a military escort to the capital Luxembourg and there to today's resting place in the crypt under the Notre Dame Cathedral .

progeny

Johann von Luxemburg married Elisabeth (1292-1330) in Speyer in 1310 , daughter of Wenceslaus II , King of Bohemia. After her death, he married Beatrix of Bourbon in Vincennes Castle in 1334 .

- Children from first marriage

- Margaret (1313-1341); ⚭ Heinrich II , Duke of Lower Bavaria (1305–1339)

- Jutta (1315-1349); ⚭ 1332 John II , King of France

- Charles IV (1316–1378), Roman-German Emperor

- Přemysl Ottokar of Luxembourg (1318-1320)

- Anna (1319-1338); ⚭ 1335 Otto , Duke of Austria

- Johann Heinrich (1322–1375), Margrave of Moravia; ⚭ Margarete , Countess of Tyrol

- Second marriage children

- Wenceslaus (1337–1383), first count, then duke of Luxembourg

Illegitimate children:

- Nicholas (1322–1358), Patriarch of Aquileia

See also

- Blanne Jang , the boiled sausage named after him, filled with cheese and coated with bacon

literature

- Marek Kazimierz Barański: King John of Bohemia and the Silesian Dukes. Editions Saint Paul, Luxembourg 1997.

- Jörg K. Hoensch : The Luxembourgers. A late medieval dynasty of pan-European importance 1308–1437. (= Kohlhammer-Urban pocket books. Volume 407). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 978-3-17-015159-8 , p. 51ff (good overview work, which also contains further references).

- Michel Pauly (Ed.): Johann the Blind. Count of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia. 1296-1346. Proceedings of the 9es Journées lotharingiennes. 22-26 October 1996. Center Universitaire de Luxembourg. Sect. Historique de l'Inst. Grand-Ducal, Luxembourg 1997, ISBN 978-2-919979-11-0 (important anthology with contributions on the life of Johann von Luxemburg, partly in German, partly in French).

- Nicolas van Werveke : Johann, King of Bohemia and Count of Luxembourg . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 14, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1881, pp. 120-148.

- Michel Pauly (ed.): The heir, the foreign prince and the country. The marriage of John the Blind and Elizabeth of Bohemia in a comparative European perspective. CLUDEM, Luxembourg 2013.

- Ferdinand Seibt : Johann of Bohemia. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 10, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1974, ISBN 3-428-00191-5 , p. 469 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Jiří Spěváček: Jan Lucemburský a jeho doba. [John of Luxembourg and his time 1296–1346. On the first entry of the Bohemian countries into the union with Western Europe]. Prague 1994, ISBN 80-205-0291-2 .

- Klaus Sütterlin: King Johann. Knight on the scene of Europe. Knecht, Landau 2003, ISBN 3-930927-77-2 .

Web links

- Iohannes Lucemburgensis Bohemiae rex in the repertory "Historical Sources of the German Middle Ages"

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cf. Regesta Imperii 6.4, No. 600.

- ^ Jörg K. Hoensch: The Luxemburger. A late medieval dynasty of pan-European importance 1308–1437. Stuttgart 2000, p. 69.

- ^ Werner Paravicini : The Prussian journeys of the European nobility. Part 1 (= supplements of Francia. Volume 17/1). Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1989, ISBN 3-7995-7317-8 , p. 147 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Michael Prestwich: The Battle of Crecy . In: Andrew Ayton, Philip Preston (eds.): The Battle of Crecy, 1346. Woodbridge 2005, pp. 139ff., See especially pp. 150, 152.

- ↑ Burial of the earthly remains of King John of Bohemia. In: The eagle. World and national chronicles; Entertainment newspaper, literary and art newspaper for the Austrian states / Der Adler / Vindobona. City of Vienna , September 12, 1838, p. 1 (online at ANNO ).

Remarks

- ↑ Munificenz comes from the Latin munificentia 'charity, charity, generosity' , see munificence . In: Herders Conversations-Lexikon . Volume 4, Freiburg im Breisgau 1856, p. 266 .

| predecessor | government office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Heinrich |

King of Bohemia 1311–1346 |

Charles IV |

| Heinrich |

Margrave of Moravia 1311–1333 |

Charles IV |

| Henry VII |

Count of Luxembourg 1313–1346 |

Charles IV |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | John of Bohemia |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Johann of Luxembourg; John the Blind; Jan Lucemburský |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | King of Bohemia and Hereditary King of Poland |

| BIRTH DATE | August 10, 1296 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Luxembourg |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 26, 1346 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Battle of Crecy |