Battle of Mühldorf

In the Battle of Mühldorf , often called the Battle of Ampfing , on September 28, 1322, the Wittelsbacher Ludwig IV. The Bavarian , Duke of Upper Bavaria , defeated the Habsburg Frederick the Fair , Duke of Austria . The disputes about the succession of the late Henry VII in the office of the Roman-German king , which had been going on since 1314, came to a military end here. Ludwig was able to assert himself as king and finally became Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire on January 17, 1328. In order to achieve a reconciliation with the Habsburgs, Ludwig recognized his adversary Friedrich as a co-king in September 1325. The battle of Mühldorf is now considered the last great knight's battle without firearms .

causes

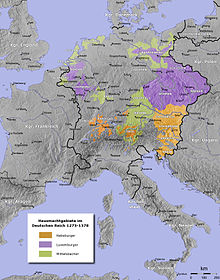

At the turn of the 13th to the 14th century, three noble families dominated political events in the Holy Roman Empire : the Habsburgs, the Luxembourgers and the Wittelsbachers. In order to put a stop to the growing influence of the Habsburgs, after the death of King Rudolf von Habsburg in 1291, it was not his son who was elected as successor by the electors, but the less influential Adolf von Nassau . Because Adolf policy aimed at expanding its power base, however, he quickly lost favor with the electors , and these replaced him seven years later by the overridden in the previous election son Rudolf, Albrecht I. After his violent death in 1308 was the Luxembourgish Count Heinrich elected King of Germany as Heinrich VII. In June 1312 he was anointed emperor in Rome, but died of malaria a year later . The dispute about his successor that followed was ultimately the starting point for the battle of Mühldorf.

The double election of Frankfurt

After Henry's death, both the Habsburgs and the Luxembourgers registered their claim to the throne. The House of Habsburg sent Frederick the Fair to fight for the throne. On the Luxembourg side, they wanted to see King John of Luxembourg , the son of the late Heinrich, on the throne. When Johann surprisingly withdrew his claims to the throne, but did not want to leave it to his rival Friedrich, he proposed the Wittelsbach Duke of Upper Bavaria and the Palatinate, Ludwig the Bavarian , as a candidate. On October 13, 1314, both candidates, Friedrich and Ludwig, came to the city of Frankfurt to vote. Friedrich left Ludwig's invitation to stand together for election to the elector unanswered, a decision that inevitably had to end in a double election. The electors from Cologne , the Palatinate and from Saxony-Wittenberg elected Frederick the Beautiful in Frankfurt-Sachsenhausen as king on October 19, 1314 . The coronation by Heinrich II. Von Virneburg , the archbishop of Cologne , then took place in Bonn , since Aachen , the traditional coronation city, refused to open the gates to Friedrich. On October 20th, one day after Friedrich's election, Ludwig was elected king in Frankfurt by electoral votes from Mainz , Trier , Bohemia , Brandenburg and Saxony-Lauenburg and on November 25th in Aachen by the Archbishop of Mainz , Peter von Aspelt , crowned.

Traditionally, the elections for kings took place in Frankfurt, the coronation itself afterwards in Aachen by the Archbishop of Cologne. In the double election of 1314, for example, there was the curious case that Ludwig the Bavarian was elected and crowned in the “right” place, but by the “wrong” archbishop. Friedrich, on the other hand, was able to show the "right" archbishop, but was crowned by him in the "wrong" place.

This was followed by mutual efforts to obtain papal approbation , i.e. the confirmation of one of the candidates by the Pope. Initially, however, he did not want to recognize either of the two pretenders to the throne in order to keep the situation open in the throne conflict and to be able to pursue his own interests. The result was an eight-year battle for the throne, in which both candidates initially had similar chances.

The way to the decision

On the basis of election promises with which he bought the favor of the electors, Ludwig ceded parts of the Wittelsbach property to Mainz, Trier and Bohemia. This angered his brother, Count Palatine Rudolf I , who had long had a dispute with him and who had voted against Ludwig in the election of the king. Rudolf now openly took the side of the Habsburgs under Frederick the Fair. A first encounter between Ludwig and Friedrich's troops ended in 1315 near Speyer without a fight. Meanwhile, the Upper Bavarian nobility tried to resolve the differences between Rudolf and Ludwig. Rudolf should therefore accept the kingship of Ludwig as well as the assignments of territory and receive the regency in Bavaria in return. Ludwig, however, did not want to grant his brother any power and secured the support of the Lower Bavarian and Upper Bavarian estates with several clever moves . Finally, Rudolf, robbed of his castles, had to flee to Worms .

In 1316 there was another encounter between the Wittelsbachers and the Habsburgs, this time near Esslingen am Neckar . It was true that there was a short battle when servants clashed while watering the horses, but since no flags were shown and the army command of both sides was not present, the result of the battle did not count. A few years of calm followed in the dispute between the two houses, which Ludwig used to expand his power in Bavaria. He was also able to agree on a settlement with Rudolf, in which Ludwig granted sole rule in Bavaria. Rudolf himself had to be satisfied with a few castles and financial achievements. Without being reconciled with his brother, Rudolf finally died on August 13, 1319 in Heidelberg . In September 1319, the troops of Frederick the Beautiful advanced to Mühldorf for the first time, where they finally faced the troops of Ludwig. Due to death threats against Ludwig, his troops withdrew without a fight, they did not want to be in danger of losing their leader. The Habsburg troops then moved, leaving a trail of devastation behind them, as far as Regensburg . As a result of this setback, Ludwig suffered an enormous loss of power, but could continue to count on the important support from Lower Bavaria. Friedrich now sensed the chance to finally get Ludwig out of the way in the fight for the throne, and in 1321 moved with his troops again towards Mühldorf, despite all warnings from their own ranks.

procedure

The approach routes of the troops

The Habsburg troops

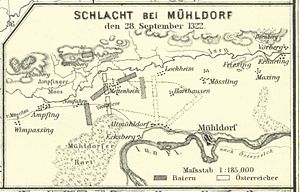

Friedrich's troops, coming from the west, united with the troops of the Passau bishop near Passau on September 21, 1322 and then moved together along the left bank of the Inn towards Mühldorf, where they arrived about five days later. Friedrich's ally, Friedrich III. von Leibnitz (the Bishop of Salzburg ) and Dietrich Bishop von Lavant moved from Salzburg to Mühldorf in the north, where they arrived before September 20th. Friedrich the Beautiful arrived in Mühldorf on September 24th. Leopold I of Austria , Friedrich's brother, was supposed to come from Swabia to join the Habsburg troops, but he did not succeed. He was still on the Lech on September 25th , so in the best case four to five days' march from Mühldorf. The armed force available in Mühldorf consisted of 1,400 helmets, heavily armed riders, 5,000 Hungarians and pagans, which means Cumans , and many warriors on foot. Duke Leopold would have had over 1200 helmets, but at the time of the battle he was still near Fürstenfeld near Munich.

The Wittelsbach troops

At the head of his troops, Ludwig moved from Regensburg towards Mühldorf on September 7, where he arrived on the day of the battle. His troops were composed of his own vassals and those of his Lower Bavarian nephews. Important allies were Johann von Luxemburg and the burgrave Friedrich IV. Von Nürnberg . But also Swabian troops under Wilhelm von Montfort and Berthold von Seefeld were used to repel the Habsburg troops. The main purpose of the Swabians is presumably to stop Leopold's advance, or to interrupt the line of communication between him and Friedrich, which they apparently succeeded in doing. The troop consisted of 1,800 heavily armed riders, 4,000 foot soldiers and riflemen.

The place of the battle

The exact location of the battle has long been extremely controversial. Some sources report that the battle took place between Mühldorf and Ötting an der Isen , while other sources state that the Ampfinger Wiesen was the site of the battle. The battle of Ampfing has therefore been talked about for a long time . Since almost all sources mention a ridge near the battlefield, the hypothesis of the location of the battle near Ampfing has meanwhile been rejected. Austrian stories from the 14th century speak of a place of the battle "Oberthalben Mühldorf". This coincides with several independent narratives that connect Dornberg Castle northeast of Erharting with the site of the battle. The hypothesis of the location of the battle in the northeast of Mühldorf makes it very probable that some sources also speak of a fight on the Erhartinger meadows . This is supported by research by Ernst Rönsch, who also provides an explanation for the mention of Ampfing in several sources. In Salzburg registers, for example, there is talk of a customs duty “to Ampfing im Rohrbach”. However, the village of Rohrbach is not located near Ampfing, but two kilometers northwest of Erharting. More recent finds also support the thesis of the site of the battle west of Erharting, which can therefore be considered safe.

The course of the battle

The information about the course of the battle is contradictory and, depending on the party, endeavors to emphasize the fame of Ludwig or to excuse the defeat of the Habsburgs. Who initiated the battle is controversial. According to the Bohemian Chronicle, King John suggested the feast day of the Bohemian patron saint Wenceslaus as the day of the battle. The victory on this Czech national holiday is then appropriately honored in the Bohemian Chronicle. The Bavarian Fürstenfelder Chronik attributes the initiative to King Ludwig, who had a lot of trouble convincing King John of the battle, and dates it to the day before Saint Michael’s Day . At least there is agreement on the date, September 28th, even with different names. The battle seems to have been offered by the Bavarian party by presenting itself to the enemy in battle order the evening before.

Since Friedrich was unable to gather all of his troops in time and was thus inferior to his opponent by 400 knights, several sides advised him not to start the battle prematurely. Despite all the dissenting votes, he accepted the fight. There is disagreement about the people involved. Whether King Ludwig himself took part in the fight is stated differently depending on the party. It seems certain that Friedrich rode into battle with a full helmet . According to older Habsburg records, Ludwig did not take part in the fight at all, a reproach that no longer appears in more recent sources. Bavarian sources admit, however, that in order to remain undetected, he joined a group of eleven other knights, which could be interpreted as unknightly behavior.

Heinz Thomas reconstructs the following course of the battle from various sources : King Johann with troops from Bohemia, Silesia and the Rhineland stood on the right wing of the Bavarian party. In the center and on the left wing stood Ludwig and Bavaria from the two duchies, as well as the troops from Franconia and Swabia. Opposite the Bohemian king were Duke Heinrich of Austria and the troops from Salzburg. After the first closed cavalry attacks, the Bavarians are said to have dismounted and together with the foot troops, the horses of the Austrians were brought down. It is not clear today why the 5,000-strong Hungarian troops fighting on the Habsburg side could not be effectively deployed. It is believed that she was inferior to heavily armored opponents due to her light armor. They were also unable to use their cavalry effectively, as the Bavarian line leaned against the slope and so it was not possible to bypass its rear. According to Austrian sources, betrayal is said to have significantly influenced the outcome of the battle. Bohemian fighters who had already been captured are said to have been freed by an Austrian and intervened in the fight. At the same time, the Nuremberg burgrave attacked with 500 knights (including the field captain Seyfried Schweppermann ) from the north-west and drove the left wing of the Austrians back towards their center. The Habsburgs initially thought the burgrave's troops were Duke Leopold's troops and could no longer counter the surprise attack. King Friedrich and his brother were captured by the Nuremberg people. According to Bavarian sources, the two Austrian brothers Ludwig threw each other at their feet in tears because they feared they would be killed. But Ludwig ordered them to rise and declared them captured.

After the end of the battle, Friedrich was first brought to Dornberg Castle and later to Trausnitz Castle . Although there is no precise information about the number of losses, these were undoubtedly quite high. The Bohemian Chronicle of Peter von Zittau speaks of around 1100 dead. The victorious Ludwig left the battlefield on the same day for fear of a possible delayed arrival of Leopold. This was again interpreted as unknightly behavior, as he did not stay on the battlefield for three days as usual to make the victory obvious. Ludwig did not allow the Habsburg auxiliary troops, who were plundering towards Austria, to be pursued any further. The members of the Austrian and Salzburg nobility captured during the battle were gradually released by the victorious parties for ransom . The city of Mühldorf, which belongs to the Archdiocese of Salzburg , was not taken. Mühldorf remained under Salzburg rule until 1802.

Effects

Despite his victory, Ludwig was initially not generally recognized as king. Nevertheless, after his victory, he took over the power of government and was also able to obtain the handover of the imperial regalia by the Austrians. Since other houses tried to intervene in the conflict over the imperial candidacy, Ludwig sought a comparison with Friedrich. After two and a half years in prison, Friedrich renounced the throne and stated that he was protecting Ludwig against everyone. In return, he only wanted to be enfeoffed with the hereditary lands and to marry his son with Ludwig's daughter. Since his brothers had to agree to this settlement, but Leopold did not do so, Friedrich was imprisoned again, the settlement was invalid. Reconciliation with the Habsburgs only came about when Ludwig recognized Friedrich as co-king in Munich on September 5, 1325 . Only on January 17, 1328 was Ludwig then crowned Roman-German Emperor in Rome , the only medieval coronation without any papal participation.

swell

- Regesta Imperii . Edited by Lothar Gross. Vol. 7.2. Innsbruck 1927, p. 151f .; here online .

literature

- Wilhelm Erben : The battle of Mühldorf September 28, 1322 historically, geographically and legally investigated . Leuschner & Lubensky, Graz-Vienna-Leipzig 1923.

- Josef Steinbichler: The battle near Mühldorf: September 28, 1322; Causes - process - consequences . Heimatbund Mühldorf, Mühldorf a. Inn 1993, ISBN 3-930033-10-0 .

- Josef Weber: The Battle of Mühldorf: A historical study on the 600th anniversary of the battle. Festschrift for the Kraiburg folk play "Ludwig the Bavarian or the dispute of Mühldorf". D. Geiger, Mühldorf a. Inn 1922.

- Bernhard Lübbers : Overlooked sources for the battle of Mühldorf 1322. In: The mill wheel. Contributions to the history of the country to Isen, Rott and Inn 61 (2019) pp. 93–102.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Steinbichler (1993), pp. 9-11

- ↑ a b c Steinbichler (1993), p. 19 ff.

- ↑ Steinbichler (1993), p. 22 ff.

- ↑ a b c d e Heinz Thomas: Ludwig the Bavarian (1282-1347). Emperors and heretics. Pustet, Regensburg 1993. pp. 101-107

- ↑ Steinbichler (1993), p. 43 ff.

- ↑ Hans Delbrück: History of the Art of War: The Middle Ages, 2nd edition 1907 as a new edition published in 2000, p. 624

- ↑ Steinbichler (1993), p. 52

- ↑ Emler (1884), p. 263

- ^ Karl von Hegel: Chronicles of the German cities . Volume 8. Göttingen, 2nd edition, 1961. P. 68.

- ↑ Steinbichler (1993), p. 50 ff.

- ↑ Steinbichler (1993), p. 59 ff.

Coordinates: 48 ° 16 ′ 35 ″ N , 12 ° 33 ′ 35 ″ E