Ludwig IV (HRR)

Ludwig IV. (Known as Ludwig the Bavarian ; * 1282 or 1286 in Munich ; † October 11, 1347 in Puch near Fürstenfeldbruck ) from the House of Wittelsbach was Roman-German King from 1314 and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire from 1328 .

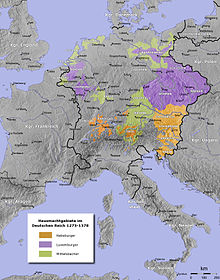

After the death of Emperor Henry VII in the Roman-German Empire in 1314, two kings, Ludwig Wittelsbach and Friedrich Habsburg, were elected and crowned. The controversy for the throne lasted for several years and in the battle of Mühldorf in 1322 a preliminary decision was made for the Wittelsbach side. The Munich Treaty of 1325 established for a short time a double kingship that was previously completely unknown to the medieval empire, and the dispute over the throne was settled. Ludwig's intervention in northern Italy sparked a conflict with the papacy that lasted from 1323/24 until his death in 1347, almost his entire reign. The Wittelsbach fell the 1324 excommunication and remained until his death in excommunication . During the conflict with the curia, the imperial constitution developed in a secular direction. In 1328 there was a “papal-free” imperial coronation when Ludwig received the imperial crown from the Roman people. Ludwig was the first Wittelsbacher as Roman-German emperor. In the 14th century, curial sources and sources close to the Pope gave it the nickname "the Bavarian" (Bavarus) in deliberate degradation . Since the 1330s Ludwig pursued a more intensive domestic power policy and acquired large areas with Lower Bavaria and Tyrol. The expansion of power also endangered the rule of consensus with the princes as an essential model of rule of the 14th century. These tensions in the equilibrium between prince and emperor led to the election of Charles IV as the opposing king in 1346 . Ludwig died under the church ban in 1347.

Life

Origin and youth

Ludwig came from the noble family of Wittelsbachers . His great-great grandfather Otto I was by the 1180 Staufer Emperor Frederick I with the Duchy of Bavaria invested. As a result, the Wittelsbachers rose to become imperial princes . However, they were not only politically loyal to the Hohenstaufen dynasty, they were also related to them. The Bavarian dukes Ludwig II the Strict , father of Ludwig of Bavaria, and Heinrich XIII. were related by marriage to the Roman-German King Conrad IV through their sister Elisabeth . Konrad's son Konradin was thus a cousin of Ludwig of Bavaria. Konradin failed to recapture southern Italy. With his execution, the Hohenstaufen died out in 1268. As a result, his uncle Ludwig the Strict inherited the Hohenstaufen possessions up to the Lech .

For the further rise of his family, Ludwig der Strenge used a marriage as a political means: on the day of Rudolf von Habsburg's coronation in 1273, he married the king's daughter Mechthild. From this marriage - his third - two sons emerged: Rudolf was born in 1274 and Ludwig, the future emperor, was born in 1282 or 1286. He was brought up together with the duke's sons at the Viennese court of Duke Albrecht I. Ludwig's “playmate” there was his cousin Friedrich the Beautiful , who would later become his rival for the royal throne. Ludwig's father died in early February 1294. Shortly after October 14, 1308, Ludwig married Beatrix, who was around eighteen from the Silesia-Schweidnitz line.

In 1310 there was a dispute between the brothers over the paternal inheritance in Bavaria. As Duke Ludwig II of Strictness had determined in his will, Ludwig shared rulership in the Palatinate and Duchy of Upper Bavaria with his older brother Rudolf I. In Lower Bavaria , where Duke Stephan I died in December 1310, Ludwig took over his cousin Otto III. the guardianship of Stephen's underage children Otto IV and Heinrich XIV . Disputes between Duke Ludwig of Upper Bavaria and the Habsburgs soon broke out over the perception of guardianship. Ludwig changed course with his brother: In the Peace of Munich on June 21, 1313, they settled their dispute and decided on a joint government for Upper Bavaria. The contract only lasted one year, but it gave Ludwig the necessary room for maneuver vis-à-vis the Habsburgs. In the battle of Gammelsdorf on November 9, 1313, Ludwig defeated the Habsburg Frederick the Handsome. Then he was able to secure the guardianship of his Lower Bavarian cousins and increase his influence in the southeast of the empire. He succeeded in finally ousting Friedrich the Beautiful from Lower Bavaria. His military success increased his reputation throughout the empire and made him a potential candidate for the upcoming royal election. During the subsequent peace negotiations in Salzburg, different symbolic signs and gestures were used to stage the peacemaking process: hugs and kisses, shared meals, shared camps, same clothes. This is passed down by both the Chronica Ludovici from the Wittelsbach perspective and the chronicle of the Habsburg-friendly Johann von Viktring . The symbolism of peace emphasized by both sides makes the later break of the agreements by the political opponent appear all the more dramatic. On April 17, 1314, a treaty concluded in Salzburg ended the disputes.

Controversy for the throne (1314-1325)

After the death of Emperor Henry VII of Luxembourg in August 1313, it took 14 months for the seven electors to elect a king . As the son of the deceased emperor from the House of Luxemburg, Johann von Böhmen initially wanted to succeed him. In addition to his own voting vote , he was able to count on the votes of Archbishop of Mainz Peter von Aspelt and his uncle, Archbishop of Trier, Baldwin . The French King Philip IV tried with his son to bring a member of his dynasty, the Capetians , to the Roman-German throne, but was unsuccessful in the election of Henry VII to the electors, as he had done in 1310. Only the Habsburgs offered serious resistance to the Luxembourgish claim to the throne. In the sphere of influence of Frederick the Beautiful (Austria, Styria, Switzerland, Alsace), a non-Habsburg king would hardly have found recognition if his throne ambition had been rejected. The Archbishop of Cologne, Heinrich von Virneburg, wanted to prevent the Luxembourgers from forming a dynasty. He assured the Habsburg that he would vote on the course.

In view of the confused circumstances, the Mainz and Trier Archbishop Johann von Böhmen persuaded to renounce a candidacy. They stood up for the Wittelsbacher Ludwig as a compromise candidate in order to prevent the Habsburg Frederick as the new Roman-German king. Ludwig had gained a reputation by his victory over Friedrich at Gammelsdorf and otherwise had sufficient charisma. In addition, the Wittelsbachers did not represent a great danger from a strong royal family because of the said fraternal dispute. From the perspective of the Luxembourgers, Ludwig was also suitable because of his extremely low power base - "he was a prince without a country" - and had neither domestic power nor significant income . In addition to the Archbishops of Trier and Mainz, Margrave Woldemar of Brandenburg was also for Ludwig. Ludwig had a good chance of being elected, but the Bohemian electoral vote was claimed by Duke Heinrich von Carinthia , who was expelled in 1310 and wanted to give his vote to the Habsburgs. The voice of Saxony was also uncertain. There both the Lauenburg and the Wittenberg lines claimed the right to vote. The Archbishop of Cologne, the Count Palatine Rudolf I of the Rhine and the Wittenberg Elector Rudolf of Saxony supported the Habsburg Frederick . The disagreement between the electors ultimately led to the election of both competitors by their respective supporters, with Ludwig's brother Rudolf voting for the opposing candidate Friedrich.

On October 19, 1314, Friedrich of Austria was made king in Sachsenhausen , and one day later Ludwig was elected at the gates of Frankfurt . Both royal coronations took place on November 25th. But they showed weaknesses to legitimize them. Ludwig was crowned together with his wife Beatrix at the traditional coronation site in Aachen, but he only had reproduced insignia and with the Archbishop of Mainz he had the wrong coronator ("King's Crown"). Friedrich was crowned by the real coronator, the Archbishop of Cologne, and was in possession of the real imperial insignia, but his elevation did not take place in the coronation city of Aachen, but in the completely unfamiliar coronation site of Bonn. In the anti-Habsburg Chronica Ludovici , it is alleged that Friedrich was elevated to king on a barrel and fell into the barrel. With this, the chronicler wanted to clarify the illegality of this king's elevation.

Both sides tried to get the Pope to recognize their rule. Pope Clement V , however, died six months before the king was elected on April 20, 1314. The chair of Petri remained orphaned until August 7, 1316, i.e. for more than two years. In this situation a military decision would have brought clarity; the outcome of the battle would have been understood as a divine judgment. Between 1314 and 1322, however, the crowned repeatedly evaded such a decision. His previous military failures gave Frederick the Fair cause for restraint: after losing to Ludwig at Gammelsdorf, the Habsburgs suffered a defeat against the Confederation on November 15, 1315 in the Battle of Morgarten . There were minor battles in 1315 near Speyer and Buchloe , 1316 near Esslingen , 1319 near Mühldorf and 1320 near Strasbourg. However, there was no major battle. The following years brought a personnel shift to Ludwig's disadvantage. Neither Ludwig nor Friedrich could take advantage of the death of Margrave Woldemar von Brandenburg (1319), but after the death of Archbishop of Mainz Peter von Aspelt on June 5, 1320, Pope Johannes XXII. Matthias von Bucheck , a supporter of the Habsburgs, as his successor. The pope, newly elected in 1316, had so far held back in the controversy for the throne, but now acted against Ludwig.

A few weeks before the decisive battle, Ludwig's first wife Beatrix died in August 1322. Three of the six children from this connection reached adulthood: Mechthild , Ludwig V and Stephan II. On September 28, 1322 Ludwig defeated his opponent Friedrich von Habsburg again in the battle of Mühldorf , where he was largely supported by the troops of the burgrave Friedrich IV von Nuremberg was supported. The Fürstenfeld monastery may even have helped the Wittelsbacher to decide the war by intercepting the Habsburg messengers. For this, the monastery was granted numerous privileges by Ludwig. Friedrich was taken prisoner. Ludwig is said to have received his Habsburg relatives with the words: "Cousin, I never saw you as much as I did today". For the next three years, Ludwig kept his cousin in custody at Trausnitz Castle in Upper Palatinate .

Ludwig's rule was not secured despite the victory, because the Habsburgs retained their hostile attitude and on March 23, 1324, John XXII was excommunicated. the king after repeatedly threatening to take this step. The Wittelsbach had without papal approval the title of Roman king out and started to operate in northern Italy in the imperial policy by close to the Papal States forgave offices and honors. The Pope even tried to subordinate Northern Italy to his influence. According to the will of the Pope, Ludwig should resign within three months and revoke all previous orders. After the deadline, the Pope imposed the excommunication. Ludwig remained under the ecclesiastical ban until his death in 1347. The king responded to the excommunication with three appellations ("Nuremberg Appellation" in December 1323, "Frankfurt Appellation" in January 1324 and "Sachsenhausen Appellation" in May 1324) to the Pope. He insisted on his right to rule through the election of the electors and coronation and declared himself ready to be justified before a council . However, the appellations were not heard by the Pope. Rather, John XXII withdrew. on July 11, 1324 Ludwig the royal rights of rule, excommunicated his loyalists and threatened him with further disobedience the withdrawal of his imperial fiefs and the Bavarian ducal dignity. The Friedrichs brothers tried to profit from the papal ban. Under the leadership of Leopold von Habsburg, they continued to resist the Wittelsbach rule.

In view of the resistance of the Habsburgs and the Pope, Ludwig decided to settle with Friedrich. In secret negotiations on March 13, 1325 in Trausnitz (' Trausnitzer Atonement ') , the prisoner Friedrich renounced the crown and the Habsburg imperial fiefs. He also had to acknowledge the Wittelsbacher's rule on behalf of his brothers. Thereupon Ludwig released the Habsburg. Friedrich did not have to pay a ransom, but had to hand over the imperial property acquired in the throne dispute to Ludwig. The Trausnitz Peace between Ludwig and Friedrich was visualized for all those present through the form of documents and symbolic actions. The agreement was ritually reinforced on Easter by the common reception of the Eucharist and the kiss of peace. The rivals heard mass together and received communion in the form of a host shared between them . The reception of the Lord's Supper gave peace a sacred character. Similar to an oath, the shared host bound both rulers to future agreement. Since the early Middle Ages, a common meal has been a common act of demonstrating peace and friendship. By sharing the Lord's Supper, Friedrich demonstratively ignored the Wittelsbacher's papal excommunication and opposed the Pope. A promise of engagement strengthened the peace treaty: Stephan, Ludwig's son, was to be married to Friedrich's daughter Elisabeth. With the Trausnitz Atonement of March 13, 1325, the controversy for the throne, which had been ongoing since 1314, ended.

Dual rule (1325-1327)

But Friedrich's brothers by no means accepted the Trausnitz Treaty. Further secret negotiations between Ludwig and Friedrich followed. Half a year later, Ludwig abandoned his claim to sole rule. In the Munich Treaty of September 5, 1325, Ludwig and Friedrich committed themselves to a dual kingship. Equal dual rule was a previously unknown political concept for the medieval empire, which was not even considered later. Friedrich was to become co-king in Germany and his brother Leopold was to receive the imperial vicariate in Italy.

Various assumptions have been made in research about Ludwig's reasons for this step. Heinz Thomas doubted that Ludwig wanted to stick to the agreement. He saw the treaty as a tactical move with which Ludwig wanted to win over the Habsburgs and, above all, Frederick's reluctant brother Leopold. In contrast, Michael Menzel , Martin Clauss and Roland Pauler assumed that the Wittelsbacher seriously intended to implement the Munich Treaty. Menzel saw the agreement as a tactical maneuver against Pope John XXII. Papal influence would become less important in the empire and an agreement with the most important princes would significantly reduce the effects of excommunication. For Clauss and Pauler, the Munich Treaty created greater scope for Italian policy. The Habsburg co-king was supposed to stabilize rule in the empire north of the Alps.

For the years of dual power, the consensus was shaped politically and symbolically. In the Munich Treaty, the two kings referred to each other as brothers. In doing so, they made clear their union as equal partners with the demand for mutual support. They did not have a double coronation, as the usual representation of power provided for only one king and the idea of monarchical rule dominated throughout the Middle Ages. In the feudal investiture, the imperial princes had to pay homage to both rulers. New seals were created to represent the dual power. Each king had his own seal, but the name of the fellow king had to appear before his own name. During the years of dual rule, the two kings demonstrated their consensus politically and symbolically. Mutual trust and unanimity were emphasized in a large number of files. The rulers referred to each other as kings, dined and drank together and even shared a bed. However, the possibilities of appropriately ceremonial expressing the previously unknown structure of rule were limited. The staging of this new concept of rule was limited to peaceful agreement. The Munich Treaty did not contain any specific provisions for the implementation of dual power. Important aspects such as coinage or communication with the princes and cities were left out. The Pope declared the contract sworn by the kings invalid.

The double kingship lasted only a short time. In Ulm, on January 7, 1326, Ludwig declared himself ready for the first time to renounce kingship if Frederick received papal approbation by July 26, 1326. But John XXII. delayed his decision and the deadline passed. Ludwig used the offer to renounce the throne as a tactical means to unite the princes and subjects behind him. The Pope could not decide in favor of Friedrich, as he had now grown too close to Ludwig. By rejecting the peace solution in the empire, the Pope appeared implacable and hard-hearted. This promoted the solidarity of the subjects with Ludwig. The two kings met for the last time in Innsbruck at the end of 1326 as guests of Duke Heinrich of Carinthia . This apparently led to tensions that may have affected the implementation of the common rule. Ludwig ended the double kingship in February 1327 when, in contradiction to the Munich Treaty, he made King John of Bohemia as Vicar General , rather than Frederick .

Situation in Italy before the start of the Rome train

The political situation in Italy in the late Middle Ages was complicated. Imperial Italy comprised large parts of central and northern Italy (excluding the Republic of Venice ) and formally belonged to the Roman-German Empire, although the Roman-German kings from the middle of the 13th to the early 14th century could no longer actively intervene there. The various city republics, where the Ghibellines and Guelphs were often hostile to one another, were politically decisive in northern Italy . However, there was no sharp division between the two groups, which can only be characterized in a very simplified manner as supporters of the emperors and opponents of the emperors. Rather, the respective city lords (Signori) primarily represented their own interests. When Henry VII (1310-1313) moved to Italy, the first since the fall of the Hohenstaufen in 1268, several Guelfi signori had tried to come to an understanding with the emperor before it came to an open break. The ultimate failure of Heinrich's move to Italy, mainly due to his early death, had further destabilized the political situation in Imperial Italy, so that the empire lost further political influence in Italy.

In addition, other powers were pursuing their own interests there. The popes had resided in Avignon since 1309 , where they were exposed to the influence of French royalty. The pope acted in the Papal States as a sovereign, while the King of Naples, southern Italy dominated. Pope John XXII. actually no longer recognized the imperial claims in imperial Italy. In 1317 he appointed the decidedly anti-imperial-minded King Robert of Naples , a grandson of the king who had defeated the Hohenstaufen, as vicar in Lombardy and Tuscany. Action was taken there against the pro-imperial forces, which were still an important power factor.

Italian train (1327-1330) and coronation as emperor (1328)

Ludwig set out on the Italian campaign in January 1327 . The request for help from imperial-minded forces in imperial Italy against the Guelphs is emphasized as a motive in contemporary Italian sources. The Lombard coronation took place in Milan at Pentecost 1327 . The Pope reacted with further measures: on April 3, 1327 he withdrew Ludwig's inherited dignity as Duke of Bavaria, on October 23 he condemned him as a heretic and denied him the remaining rights to his property. In the papal correspondence the Wittelsbacher was only disparagingly referred to as Ludovicus Bavarus ("Ludwig the Bavarian"). With this he was denied any rank and any dignity. The Pope's measures did not prevent the king from continuing the Italian march. Ludwig had to struggle with far fewer difficulties in Italy than his predecessor Henry VII, who, however, had also pursued more far-reaching plans than Ludwig, in particular the establishment of a permanent imperial administrative structure. At the beginning of January 1328 the Wittelsbacher reached Rome and was welcomed with jubilation by the people. At the head of the Roman nobles who supported him was Sciarra Colonna , who proved to be the "fulcrum of the cooperation" between the Romans and Ludwig. Sciarra initiated an alliance of the baronal families, i.e. the large, landed nobility, with the Popolaren, i.e. the political protection association of the citizens of Rome. On this basis, Ludwig was able to stabilize his rule in Rome from January to August 1328.

In Rome, the Wittelsbach was born on January 17, 1328 in St. Peter's Church by the three bishops Giacomo Alberti from Prato , Bishop of Castello (which belonged to Venice ), Gherardo Orlandi from Pisa , Bishop of Aléria (in Corsica ) and Bonifazio della Gherardesca from Pisa , Bishop of Chiron (in Crete ) and crowned emperor by four Syndici of the Roman people. The depiction of Ludwig's enemies, according to which the imperial coronation took place without spiritual participation and the Roman people alone was its author, was exposed as misleading by Frank Godthardt. After the imperial coronation, Ludwig IV began to stage imperial power and emphasized its divinity. The imperial seal shows him in a priestly robe with a crossed stole and an open cope . The depiction of his priestly appearance in the seals comes from the time after the imperial coronation against papal resistance. Franz-Reiner Erkens observes “an intensifying display of the ruler's sacredness tinted in the sazerdotal” and interprets it as “efforts to legitimize power” in the bitter disputes with the papacy. On April 18, 1328, the emperor deposed the Pope. On May 12, 1328 the people and clergy of Rome elected the Franciscan Peter von Carvaro as the new Pope. He took the name Nicholas V on. The Wittelsbacher introduced him to the office. At Pentecost on May 22, 1328, the new Pope Ludwig crowned Ludwig in St. Peter's Church. Through these acts, Ludwig tried to strengthen the legitimation of his emperor's dignity. Nicholas, however, was of no importance as Pope. He resigned in 1330 and submitted to John XXII.

While he was still on his way to Italy on August 4, 1329, Ludwig regulated the succession of the Wittelsbach family in the Pavia house contract with Rudolf II and his brother Ruprecht I. Ludwig received Upper Bavaria and left the Palatinate to his brother's descendants. In the event of the extinction of one of the two lines, the legacy should fall to the other. The two main lines of Wittelsbach thus created remained separate until 1777. In February 1330, Ludwig returned from Rome. He became the sole ruler because Frederick the Beautiful had died on January 13, 1330. During Ludwig's absence, Friedrich had hardly been able to develop any activity worth mentioning in the empire. After the end of the Italian campaign, Ludwig founded the Ettal Abbey near Oberammergau at a strategically important Alpine crossing in 1330 .

In a document dated November 19, 1333, Ludwig offered to renounce kingship in favor of Heinrich XIV of Lower Bavaria . The empire was left out of the document. The plan to just renounce the kingship is used in research as a diplomatic ruse of the Wittelsbacher in the negotiations with Pope Johannes XXII. viewed. Again Ludwig took advantage of the offer to resign from office in order to get the princes behind him and win sympathy among his subjects.

Intensification of sovereignty

In the 1330s, Ludwig began to intensify his rule. With the Upper Bavarian Land Law of 1346 , all rights should emanate from the sovereign. This was a code of law that should be the legal basis for all court decisions in Upper Bavaria. The land law was written in German and was only valid in Upper Bavaria. Only in the 17th century was there a uniform jurisdiction for the whole of Bavaria. In individual areas, Ludwig's Upper Bavarian land law was valid until the beginning of the 19th century. In 1334 Ludwig committed his sons to an inheritance regulation. Should one of his sons die, his property should fall back to the Wittelsbach family. The unity of family and property should be preserved.

Relationship to the north of the empire

Ludwig was more active than his predecessors in the north of the empire that was “far from the king”. After the Ascanians died out in 1319, he appointed his underage son Ludwig V as Margrave of Brandenburg in April 1323 . As Ludwig's guardian, Berthold VII von Henneberg-Schleusingen was granted numerous privileges and freedoms and was intended to form a counterpoint to the Luxemburgers. Brandenburg brought the House of Wittelsbach a second vote in addition to the Palatinate vote. The Bohemian King Johann had also made claims on Brandenburg. He wanted the margraviate as compensation for his renunciation of the Roman-German throne, but only received the Altmark , the Lausitz and Bautzen . Ludwig's intervention in Brandenburg resulted in a permanent estrangement from Johann. The emperor intended primarily to strengthen the empire, and only secondarily to increase the Wittelsbach power. He wanted to prevent a further increase in Luxembourg power and thus a parallel imperial power. Ludwig secured the takeover of Brandenburg through marriage agreements. Ludwig the Brandenburger, as he was later called, was married to the Danish king's daughter Margarete in November 1324. Ludwig also intervened in the Thuringian-Meissnian area. The Wettiner were tightly bound as Margrave of Meissen and Landgrave of Thuringia to the Wittelsbach family and the kingdom. Ludwig's eldest daughter Mechthild was married to Friedrich II the Serious. As a result, Ludwig prevented a close bond between Bohemia and the nearby margraviate of Meißen. In the event of his son's death, Ludwig decided in 1327 that his son-in-law Friedrich should inherit the Mark Brandenburg. In the same year the deed of mortgage was issued for Ludwig the Brandenburger. With the hereditary brotherhood of Friedrich von Meißen by marriage and the deed of lease, the Wittelsbach family policy only began in 1327.

In 1324 the dynastic connection to Holland-Hainaut followed. Ludwig married Margarete , the eldest daughter of Count Wilhelm III. from Holland-Hainaut. The count also owned Zealand and Friesland. The following children emerged from the connection with Margaret of Holland: Margarete (1325–1360 / 1374), Anna (around 1326–1361), Elisabeth (1324 / 1329–1401 / 1402), Ludwig VI. (1328 / 1330–1364 / 65), Wilhelm I. (1330–1388 / 1389), Albrecht (1336–1404), Otto V. (1341 / 1346–1379), Beatrix (1344–1359), Agnes (1345– 1352) and Ludwig (1347–1348).

A legal dispute that lasted for decades between the Teutonic Order and Poland prompted Grand Master Dietrich von Altenburg to seek reference to the Reich at the end of the 1330s. Ludwig used this opportunity to increase the imperial power beyond the north-eastern border with the help of the order. His younger son Ludwig VI. , called the Roman, he married the Polish king's daughter Kunigunde. This tied Poland more closely to the empire. In November 1337 the Emperor transferred Lithuania, which did not belong to the Empire, to the order. If the order's campaigns were successful, the profit would go to the order and sovereignty over Lithuania would be awarded to the empire. In March 1339, Ludwig asked the Teutonic Order Master to take the city and diocese of Reval and Estonia. In the Peace of Kalisch in 1343 , Poland and the Teutonic Order were able to settle their disputes. The protection of the empire against Poland requested by the order was dropped, so the emperor lost some leverage.

Several territorial princes ( Pomerania-Stettin , Jülich , Geldern ) were upgraded in their rank by Ludwig. The enfeoffment of his son with the Mark Brandenburg led to violent clashes with the Pomeranian dukes. As a result of the enfeoffment, Pomerania was again referred to as the Brandenburg fiefdom. In August 1338, the dukes Otto and Barnim III. Detached from Pomerania-Stettin from the feudal association of the Margraviate of Brandenburg and thus directly committed to the crown. Ludwig raised his brother-in-law, Count Wilhelm von Jülich , to margrave in 1336 and imperial marshal in 1338. Count Rainald II of Geldern was made duke in 1339. Ludwig's political reorganization in the north-east of the empire shaped the situation well into the 15th century.

Alliances with England (1338) and France (1341)

To protect the interests of the Reich, Ludwig tried to bind neighboring sovereigns to himself. In July and August 1337, alliance agreements were concluded between the Empire and England. This resulted in an alliance in 1338. In September 1338 a court day took place in Koblenz, which is often regarded as the high point of Ludwig's reign. Almost all the electors and numerous greats were present. In addition, King Edward III. came from England . Personal meetings between king and emperor were rather unusual in the Middle Ages. In a higher-ranking society, border locations were preferred at rulers' meetings in order to make the equality clear. This time the English king made his way into the empire to the emperor. On September 5, Ludwig appointed Eduard III in Koblenz. as imperial vicar for " Gaul " and Germany. Eduard was allowed to act as the emperor's deputy. He was supposed to pay 400,000 guilders to Ludwig and for this the Kaiser was supposed to provide 2000 armored riders. The war alliance did not come about, however; Eduard did not pay and Ludwig did not provide an army.

In January 1341 Ludwig changed course and entered into an alliance with the French King Philip VI. a. The change of alliance took place against the background of the Hundred Years War and from this point of view has received a lot of research attention. But Ludwig did not intervene in the war. Rather, his policy was aimed at the stability of the crown violence. In April 1341 Ludwig withdrew the imperial vicariate that had been awarded in Koblenz.

Relationship with the Jews

The Jews were directly subordinate to the emperor and had to pay taxes to protect him ( chamber servitude ). Ludwig did not accept persecution of the Jews as an attack on his own majesty. In 1338 there were riots against Jews in Alsace. The oppressed fled to the imperial city of Colmar . As a result, Ludwig drove out a violent group of persecutors of the Jews who were besieging Colmar. He also took action against attacks on Jewish communities several times. In Ludwig's time, no pogroms were favored . In the contemporary assessment, Ludwig's pro-Jews policy was criticized.

court

Until well into the 14th century, medieval royal rule in the empire was exercised through outpatient rulership practice. There was neither a capital nor a permanent residence. The center of the empire was where Ludwig stayed with his court. The court was the news and communication center of the empire. Given that there were hardly any fixed structures, personal relationships at court were crucial. On the “difficult path to the ruler's ear”, subordinates had no prospect of being heard without the intercession of the Wittelsbacher's closest confidants.

The most important part of the court was the chancellery . Under Ludwig, the proportion of German documents compared to Latin ones increased sharply since the return of the emperor in 1330 on German soil. By 1330, the ratio of Latin (49 percent) and German document transmission (51 percent) in the office was almost balanced. From 1330 it shifted significantly to the vernacular, insofar as 189 German and only 30 Latin documents were issued. In contrast to the English, French and Sicilian kings, who stylized themselves as knightly, pious or wise kings, Ludwig emphasized his imperial primacy and distinguished himself as emperor and lord of the world. To this end, he used the “rhetoric of power” in his diplomas, following the example of his predecessors. He highlighted the imperial grace generously bestowed on deserving subjects. As emperor he graciously hears their requests and thus encourages the zeal of his subjects. At the same time he is honoring the office given by God.

Ludwig spent 2000 days in Munich during his 33 years of rule , 138 stays there are verifiable, but only 19 percent of the documents of the Reich Chancellery were issued in Munich. There were no royal court days or imperial assemblies in Munich. Despite all the importance that Munich had for the Wittelsbacher, there can be no question of a royal seat or even a center of the empire in the time of Ludwig of Bavaria. Apart from Munich, Ludwig stayed particularly often in the imperial cities of Nuremberg and Frankfurt. This is reflected in his deeds: after Munich (992), Ludwig did most of his deeds in Nuremberg (738) and Frankfurt am Main (699).

Robert Suckale saw a style-forming artistic center in the courtyard. He spoke of a targeted "court art of Ludwig of Bavaria". Suckale's research received both broad approval and criticism. He based his view mainly on 22 works a. a. from Munich (Anger-Madonna, Christophoroskonsole), Nuremberg (figures of the Epiphany and Apostle cycle in St. Jakob), Frankfurt ( Trumeaumadonna of the collegiate church St. Bartholomäus ) and Donauwörth (tomb of the Teutonic Order Commander Heinrich von Zipplingen ). None of these works is secured as a commission from the Wittelsbacher. The works cited by Suckale for his thesis can be broken down into several heterogeneous style groups and are related in very different ways to the imperial court and its surroundings.

At times important lawyers and theologians stayed at the imperial court. Several Franciscans and Parisian theologians came to Ludwig who, like him, were in conflict with the papacy. In the period 1324–1326 the Parisian scholars Marsilius of Padua and Johannes von Jandun joined the Wittelsbacher, in 1328 Michael von Cesena , Bonagratia von Bergamo and Wilhelm von Ockham , who were involved in the poverty dispute with the papacy , sought refuge with the emperor. The older thesis that the Old Court was a kind of “court academy” cannot be upheld. Ludwig took little interest in the intellectual debates and discussions that took place at his court. He used his ignorance as a justification to put the blame in the conflict with the papacy on his advisors.

Theoretical argument between emperor and pope

Already at the end of the reign of Henry VII there was a theoretical discussion regarding the position of the empire and the relationship to the papacy. While the emperor emphasized the imperial universal claim and independence from the papacy in his coronation encyclical of June 1312, shortly after Henry's death Clement V issued the bull Romani principes , in which the emperor was degraded to a vassal of the papacy.

The fundamental debate regarding the position of the empire continued during the reign of Ludwig. Pope John XXII. emphasized the papacy's claim to power also in secular questions, whereby curialist authors (such as Augustine of Ancona and Alvarus Pelagius ) wrote corresponding treatises. Wilhelm von Ockham and Marsilius von Padua, on the other hand, were on Ludwig's side, both of whom were influenced by the political philosophy of Aristotle . Wilhelm von Ockham, who had positioned himself against the Pope in the poverty struggle, wrote the (incomplete) so-called Dialogus, a constructed dialogue between a scholar and his pupil. Among other things, the thesis was put forward that the Pope could also be wrong and even be a heretic. Above all, this by no means has an all-encompassing plenitudo potestatis . At the same time, Ockham emphasized the importance of the imperial universal monarchy.

Marsilius of Padua dedicated his work Defensor pacis ("Defender of Peace") explicitly to Ludwig, to whose court he went in the period 1324-1326. Marsilius primarily addressed the "good life" in a political community, what conditions must be present for it and what the corresponding goals are. The primary goal in a state community is peace and its preservation, with Marsilius emphasizing the role of the citizens and putting that of the church into perspective. Marsilius resolutely rejected the papacy's claim to absolute power, advocated by curialist authors such as Aegidius Romanus and Jakob von Viterbo , and criticized the papal claim to rule in secular questions, which disrupted the peace of the community.

The Würzburg canon Lupold von Bebenburg also sided with Ludwig. In his work Tractatus de iuribus regni et imperii Romani (“treatise on the rights of the Roman kingdom and empire”) he separated between secular and spiritual power and emphasized the rights of the Roman-German kingdom. In contrast to other pro-imperial theories of rule, the universal empire did not play a decisive role in Lupold's considerations; At the same time, however, he emphasized the independence of the Roman-German monarchy vis-à-vis the papacy and strictly rejected the papal license to practice medicine.

Constitutional development

The conflict between the emperor and the pope led to the formation of a new consciousness of the empire. Princes, clergy, cities and subjects stood behind Ludwig. Only the Dominicans followed the papal instructions. The imperial constitution became increasingly condensed and developed in the direction of a secular understanding of the state.

On July 16, 1338 the " Kurverein von Rhens " took place with six electors . Majority voting should apply to the election of a king. The elected do not need papal approvals. Three weeks later, on August 6, 1338, on a court in Frankfurt, the laws on the power of attorney for imperial power " Fidem catholicam " and " Licet iuris " were promulgated. The Roman kingship was based on the majority decision of the electoral princes. With the election by the electors, the new king was also allowed to exercise the rule of Roman emperor. Intervention by the Pope was rejected. The kingship was connected with the empire. The imperial coronation in Rome by the Pope was thus superfluous. With these views on the imperial idea, Ludwig anticipated some developments in modern times. It was Maximilian I who first called himself “Elected Roman Emperor” in 1508. From the second half of the 16th century, the election of the prince electors in Frankfurt produced not only the king but also the emperor.

In September 1338 a court in Koblenz confirmed the Rhenser and Frankfurt announcements again. Ludwig was able to mobilize almost all the greats of the empire for the court day in Koblenz in 1338. The court days of 1338 were also the time of greatest support from the imperial episcopate. Johann von Böhmen also gave up his aloof attitude towards Ludwig and submitted. At the Frankfurter Hoftag in 1339, everything that had been said was confirmed once again. According to Michael Menzel, "the series of struggles for demarcation and integration" was over. Ludwig was at the height of his power. The inclusion in later manuscripts proves the importance of the imperial laws for the constitution of the late medieval empire.

Last years

In 1340 the ducal line died out in Lower Bavaria and the land fell to Upper Bavaria. The union brought Ludwig a great gain in power. After the partition of 1255 , Bavaria was reunited for the first time, but without the Upper Palatinate. In the 1340s, Ludwig took the opportunity to secure the state of Tyrol for the Wittelsbachers. In doing so, however, he also impaired relations with the Luxembourg and Habsburgs. In 1330 the marriage between Margarete , the then twelve-year-old heir daughter of the County of Tyrol, and the eight-year-old Johann Heinrich von Luxemburg , the younger son of King John of Bohemia and brother of Charles of Moravia, who later became Emperor Charles IV . The rule of the Bohemians met increasing resistance in Tyrol. A fait accompli were created in secret agreements between Margarete and Emperor Ludwig. After a hunting excursion in November 1341, the castle gate of Castle Tyrol remained closed to Johann Heinrich . Locked out, he had to leave Tyrol. In February 1342, Ludwig compelled his son, Margrave Ludwig of Brandenburg, to marry Margaret of Tyrol, even though the marriage between Margarete and Johann Heinrich had not been declared invalid. According to the procedure customary at the time, only an ecclesiastical process and thus the Pope could have annulled the marriage. As a result of this behavior, Ludwig finally became hostile to the Luxembourgers. Johann von Böhmen fell away from the Wittelsbacher. The Tyrolean affair also had far-reaching consequences for the Luxembourg-papal alliance. On April 25, 1342 Pope Benedict XII. died. The new Pope Clement VI. was a close confidante of Charles of Moravia. Both tried to push through a new election in the empire, with which Ludwig should be replaced by Karl.

Ludwig's brother-in-law, Count Wilhelm IV of Holland, died on September 26, 1345, leaving no heir. His sisters could make claims. His eldest sister Margarete was able to assert herself in the three counties with the help of her husband, the emperor. By acquiring the counties of Tyrol (1342), Holland, Hainaut, Zealand and Friesland (1346), the Wittelsbacher had achieved significant territorial gains in the last years of his rule. In doing so, however, he neglected reaching a consensus with the princes as an elementary model of rule and increasingly encountered their resistance. He failed when he tried to get his son Ludwig the Brandenburger through as co-king. Even Baldwin von Trier, Ludwig's most loyal prince, changed sides on May 24, 1346. John of Bohemia began to set up his son Charles of Moravia as the future king. From 1344 Ludwig bound the four imperial cities of the Wetterau ( Frankfurt , Gelnhausen , Friedberg and Wetzlar ) against the Luxembourg-papal alliance. On April 13, 1346 Pope Clement VI. the final papal curse on the emperor and called on the electors to a new election.

On July 11, 1346, the Moravian margrave Karl was elected (counter) king by the three Rhenish archbishops, including the Mainz archbishop Gerlach von Nassau , as well as the Bohemian and Saxon votes. Karl's influence, however, remained limited. The election took place in Rhens , as Frankfurt was on the imperial side. On November 26th, 1346, Charles had to be crowned in Bonn, because Aachen stuck to Ludwig. There were no protracted conflicts over rule in the empire, however, as Ludwig died unexpectedly in the autumn of the following year while hunting in Puch near Fürstenfeldbruck . He may have suffered a stroke and fell from his horse. He was buried in a high grave in the choir of the Marienkirche in Munich , the predecessor of today's Frauenkirche . For reasons of ban, no details have been passed on about the funeral. After Ludwig's death, the Marienkirche developed into the burial place of the Wittelsbach family. Despite the excommunication, Ludwig managed to "swear to his legitimacy and orthodoxy" to the population and clergy. Michael Menzel counted 26 necrologies in which a memory of Ludwig is handed down. Ludwig linked the memory of his person and his family with public holidays such as Candlemas (February 2nd) or St. Mark's Day (April 25th). It was not the actual date of the event that was thought that was decisive, but the public effect. Ludwig's memory was able to benefit from the gatherings of the numerous prayers for the church festival activities. Ludwig's descendants continued this new form of remembrance.

Karl was gradually able to assert himself as the new ruler in the empire. In February 1350, the Wittelsbachers also recognized him as the new king and undertook to deliver the imperial regalia. After Ludwig's death, the Wittelsbach possessions were divided several times ( 1349 , 1353 , 1376). It came to the earlier separation of Upper and Lower Bavaria. Ludwig the Brandenburger took over Upper Bavaria, Tyrol and Brandenburg. His brother Stephan II received Lower Bavaria and the property in the Netherlands. In 1392 four lines were established for a longer period of time with Upper Bavaria-Munich , Upper Bavaria-Ingolstadt , Lower Bavaria-Landshut and Lower Bavaria-Straubing-Holland .

Domestic power against the Luxembourg and Habsburgs could not be maintained for long. Tyrol fell to the Habsburgs in 1363 and Brandenburg to the Luxembourgers in 1373. Holland, Hainaut, Zealand and Friesland were lost in 1425. The Wittelsbach family, however, was able to secure the rulership complex in Bavaria until the 20th century.

effect

Late medieval judgments

In the 13th and 14th centuries, significantly more documents were drawn up than before, and the written form increased significantly. Around 5000 documents have been handed down from Ludwig. The importance of the document system also became clear in the forms of text preservation. The registers introduced by Henry VII at the imperial level were systematically continued on a large scale by Ludwig.

One of the most important historiographical sources is the imperial chronicle of Matthias von Neuchâtel , who was active in the diocese administration in Basel (1327) and Strasbourg (since 1329). As envoy to the curia, he is well informed about the curial developments during the reign of Ludwig the Bavarian. Matthias von Neuenburg was friendly to the Habsburgs and dubbed Ludwig as emperor mostly only as “the prince”. The chronicle of the Eichstätter cleric Heinrich Taube von Selbach , which extends from the 1290s to 1363, is divided into a Ludwig-friendly part until 1343 and a very antiquarian part afterwards. The two different parts of the chronicle depend on the political position of the Eichstätt bishop. During the drafting period, the bishop of Eichstätt, who was dependent on the emperor, was replaced by a bishop approved by the pope. The Chronica Ludovici was probably created in the Augustinian canons of Ranshofen in large parts in 1341/42 and was then supplemented by additions until 1347. She is strongly anti-Habsburg and speaks about Ludwig in a panegyric form. Giovanni Villani from Florence was a bitter enemy of the Wittelsbacher. In his chronicle, he passed a devastating judgment on the Italian march and the coronation of the emperor. For him, the bishops involved were “schismatics and banned”. Villani emphasized the unheard-of and unique of the Wittelsbacher's coronation as emperor: “And just imagine how arrogant this cursed Bavaria was. Because in no older or more recent chronicle have I found that any other Christian emperor ever allowed himself to be crowned by anyone other than the Pope or his legate [...]. ”The contemporary historiography that emerged in the context of the French royal court reported on the events in Rich seldom and then only barely. Only Ludwig's Italian march 1327-29 received more attention.

The Wittelsbacher's sons were born in September 1359 by Bishop Paul von Freising on behalf of Pope Innocent VI. released from the church ban. However, the curia did not allow the Wittelsbacher to be reassessed until several decades after his death. In the curious course of business in 1409, the pious commemoration of the Wittelsbacher Ludwig no longer caused a scandal when the privileges were confirmed. In 1430, Pope Martin V responded to a request from the Bavarian Dukes Ernst and Wilhelm of Bavaria-Munich to resolve the infamy of the offspring of a heretic himself. Since around 1480 and thus around 130 years after the death of Ludwig of Bavaria, he was again referred to as emperor at the curia. However, the excommunication was never lifted.

In the controversies between followers of the emperor and the papacy, in addition to traditional judgments about the ruler's physical constitution, the question of his scholarship was also raised for the first time when the Wittelsbacher spoke of a controversy with the pope about his orthodoxy at the court day in Frankfurt on August 6, 1338 let in. Due to the protracted conflicts with the Pope, the theoretical discussions about rule increased. The theoretical discussion about rule and empire reached a considerable differentiation of the individual positions. For Engelbert von Admont , Dante Alighieri , Wilhelm von Ockham and Lupold von Bebenburg , however, the emperor was still regarded as chosen by God and his rule as universal.

The battle between the Emperor of Wittelsbach and the papacy became less important soon after his death. In the empire, Ludwig played no special role in historiography from 1370 to 1500. In the historiographical works in Bavaria, however, he was recognized as an important figure. The Wittelsbachers used their imperial ancestors for political purposes. Ludwig was the common ancestor of all Bavarian branches of the Wittelsbach dynasty. The dynastic branch that wanted to reunite the duchy tried to appear as the descendant and legitimate heir of Ludwig of Bavaria. The image of Ludwig as the reunification of Bavaria and ancestor of all Wittelsbachers of the 15th century becomes clear in the Bavarian chronicler Andreas von Regensburg .

Early modern age

Since the 15th century, numerous architectural and art monuments have been erected that are reminiscent of Ludwig. The monuments had very different goals. Ludwig's importance for Bavarian history lies in the fact that he was one of the two emperors of the Wittelsbach dynasty. With their imperial ancestors, the princes from the House of Wittelsbach tried to demonstrate the historical greatness of their dynasty and to justify their rulership claims. The Bavarian dukes Albrecht IV and Maximilian I wanted to emphasize the dynastic unity and the imperial dignity of the Wittelsbach house with Ludwig's burial place in the Munich Frauenkirche, which was newly built in 1470. On the cover plate of the late Gothic imperial tomb, Emperor Ludwig can be seen on a throne in the upper half of the picture. The lower half of the picture shows the inner dynastic reconciliation between Duke Ernst , the great grandson of Emperor Ludwig, and his son Albrecht III. The topic was probably chosen by Albrecht IV because the agreement was decisive for his father's marriage to Anna of Braunschweig and for the continued existence of the dukes. In the image program, Ludwig is elevated to the patronage of the unity of the Wittelsbach house.

Duke Maximilian I had a special sympathy for Ludwig the Bavarian. In 1617/18, the Dominican Abraham Bzovius , as the editor of the 14th volume of the Annales Ecclesiastici , a standard work of church history, expressed violent criticism of Ludwig the Bavarian. Bzovius questioned its orthodoxy and the legality of his kingship. For Maximilian, the criticism of Ludwig was also a criticism of the emperor's worth of the Wittelsbach dynasty. Therefore, he advocated a diplomatic revocation of the work and first commissioned his archivist and secret councilor Christoph Gewold and then the rector of the Munich Jesuit college Jakob Keller to prepare a letter of defense. The curia gave way at the end of 1627 after lengthy diplomatic negotiations. From 1601 Maximilian undertook an extensive redesign of the imperial tomb. He took care of the memorabilia of his imperial ancestors and linked them with the wills of his father and grandfather. In 1622 he had the mausoleum of Ludwig of Bavaria built over the late Gothic imperial grave in the Frauenkirche in Munich. Of the successors of Maximilian, only the Elector and Emperor Charles VII pursued increased memory maintenance. Karl tried to historically underpin his imperial claims on Austria. Ludwig occupied a prominent place in the ancestral gallery built between 1726 and 1729/30 in the Munich Residence.

Ludwig was the Cistercian Abbey of Fürstenfeld as an imperial benefactor and guarantor of the dignity of the monastery. In times of crisis, the Abbey and Convent of Fürstenfeld hoped that their memory of Ludwig as an imperial patron would protect them from the abolition of their monastery. In the 16th century, a free-standing tumba was created as a representative donor's tomb. In 1766 two donor portraits of Ludwig the Strict and Ludwig of Bavaria, carved from wood by the sculptor Roman Anton Boos, were erected. In the second half of the 18th century, Fürstenfeld feared that the state's domestic policy against the church would be disadvantageous, and the monastery even threatened to be abolished. On the 450th anniversary of the emperor's death in 1797, a sign of the connection with the Wittelsbach rulers should be set. Delayed by the coalition wars, the marble obelisk was erected as a memorial in Puch in 1808/09 .

As Karl Borromäus Murr observed, a secularization of memory took place in modern times , which increasingly freed itself from the context of a religious memoria. Access to the history of Ludwig of Bavaria by Wittelsbach descendants, historiography and poetry of the 18th and 19th centuries was always based on interests and tied to the location. The enlightened Peter von Osterwald saw the Wittelsbacher as a historical figure in argument for a Bavarian state church policy. For Michael Adam Bergmann , Ludwig was a pioneer of bourgeois emancipation, for Lorenz Westenrieder he appears as the embodiment of an enlightened ruler. In the Kaiser-Ludwig-Schauspiel by Johann Nepomuk Längenfeld from 1779, Ludwig became an anti-Austrian symbol. The Bavarian Elector Karl Theodor agreed to Emperor Joseph II to exchange Bavaria for the Austrian Netherlands . The War of the Bavarian Succession , which was triggered off in 1778/79, made the Austrian threat in Bavaria acute. Before the exchange plans that became public in 1778, the play met with great interest from the public.

Modern

Public honors

In 1806 the Electorate of Bavaria was elevated to a kingdom. Ludwig was used for the historical legitimation of the young Kingdom of Bavaria. In 1809 the Bavarian Academy of Sciences took the initiative to research the history of the Wittelsbacher. King Ludwig I had the dilapidated Isartor renewed from 1833 to 1835, with Ludwig the Bavarian on the program as a symbol of a mutual loyalty commitment between monarch and people. The Bavarian king also financed the portrait of Emperor Ludwig of Bavaria created by Karl Ballenberger for the Imperial Hall in Frankfurt . Nevertheless, King Ludwig had an ambivalent relationship with Ludwig the Bavarian. He had the bust of the emperor removed from the Walhalla because he did not consider him a great monarch because of his breach of his word with Frederick the Fair before the king's election in 1314. His son Maximilian again confessed to Ludwig the Bavarian without reservation. No less than 13 Ludwig-der-Bayer dramas were written during his reign.

In the late 19th century, Ludwig was remembered in Bavaria as the giver of privileges. In 1877, Anselm von Feuerbach created the painting Kaiser Ludwig the Bavarian Granted Privileges to the Citizens of Nuremberg , which the Nuremberg Chamber of Commerce had commissioned for their meeting room. Eduard Schwoiser completed the mural Kaiser Ludwig the Bavarian in 1879 and gave the city of Landsberg city rights . It is located in the ballroom of the Landsberg town hall. With the end of the monarchical government in Bavaria, the political claims of Ludwig of Bavaria also lost importance. It became almost exclusively an object of medieval research.

In June 1967, the almost six meter high bronze equestrian statue by the Munich sculptor Hans Wimmer was erected in the courtyard ditch in front of the gate of the Old Court . In 2013 it was included in the Bavarian list of monuments. In December 1973, 660 years after the Battle of Gammelsdorf, the shooting club "Ludwig the Bavarian" was re-established. Ludwig's nickname “the Bavarian” is no longer a swear word, but rather “country team cohesion” is in the foreground.

research

Older research interpreted Ludwig's rule as a historical transition period between the “imperial glory” of the Hohenstaufen and the hegemonic kingship of Charles IV. According to Sigmund von Riezler , Ludwig the Bavarian was “so insignificant” in terms of “spirit and character” “that any sustainable development would trigger him the events had to fail ”.

More recent research has put this view into perspective. According to Jürgen Miethke , the importance of the Wittelsbacher lay in his ability to integrate, as he succeeded in “including important forces, especially the electors, in his lines of defense”. Ludwig had "set the course that would determine the direction of future developments for a long time". Michael Menzel called the reign of Ludwig “the time of drafts” because of the radical changes and new ideas in the empire, constitution and society. In 1993 Heinz Thomas presented a modern biographical account of the ruler and his time. On January 23, 1996, a conference was dedicated to Ludwig the Bavarian as sovereign. A colloquium was held in the former Cistercian monastery of Fürstenfeld on the 650th anniversary of the emperor's death on October 11, 1997. The conference proceedings were published in 2002.

On October 20, 2014 it was the 700th anniversary of the Wittelsbacher's election as king. On this occasion, the international conference “Ludwig the Bavarian (1314–1347). Empire and Reign in Transition ” takes place at the Historical College in Munich. The focus was on the changes and the numerous new approaches in the empire, in the constitution and in the practice of power of the Wittelsbacher. The articles were published in spring 2014. The House of Bavarian History organized the Bavarian State Exhibition “Kaiser Ludwig the Bavarian” from May to November 2014 in Regensburg and published a catalog. On the occasion of the anniversary and the Bavarian State Exhibition, Martin Clauss presented a description of the person and rule of Ludwig IV. For Clauss, Ludwig was successful in two areas: "As king and emperor, he emphatically rejected the papal license to practice medicine - as a duke he pushed ahead with the intensification of national rule."

swell

historiography

- The Chronicle of Johann von Winterthur , published by Friedrich Baethgen (MGH Scriptores rerum Germanicarum NS 3), Hanover 1923.

- Johann von Viktring, Liber certarum historiarum , edited by Fedor Schneider (MGH Scriptores rerum Germanicarum 36), Hanover / Leipzig 1909/10.

- Chronica Ludovici imperatoris quarti . In: Bavarian Chronicles of the XIVth Century , edited by Georg Leidinger (MGH Scriptores rerum Germanicarum 19), Hanover / Leipzig 1918.

- History of Ludwig of Bavaria. After the translation by Walter Friedensburg, revised and edited by Christian Lohmer. 2 vols. Phaidon, Essen / Stuttgart 1987.

Certificates

- Regesten Emperor Ludwig of Bavaria (1314–1347). Organized by archives and libraries. Edited by Peter Acht and Michael Menzel, Cologne et al. 1991ff [previously published: Volumes 1–11, 1991–2018] ( detailed overview of publications online )

literature

Representations

- Konrad Ackermann , Walter Jaroschka (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian as a Bavarian sovereign. Problems and state of research. Festschrift for Walter Ziegler (= magazine for Bavarian national history. Volume 60.1). Beck, Munich 1997 ( digitized version ).

- Martin Clauss : Ludwig IV. The Bavarian. Duke, King, Emperor. Pustet, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2560-4 .

- Martin Kaufhold : Gladius spiritualis. The papal interdict over Germany in the reign of Ludwig of Bavaria (= Heidelberg Treatises on Middle and Modern History. New Series, Issue 6). Winter, Heidelberg 1994, ISBN 3-8253-0192-3 .

- Michael Menzel : The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbook of German History . Vol. 7a). 10th, completely revised edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-608-60007-0 , pp. 153-191.

- Michael Menzel: Ludwig the Bavarian. The last battle between the Empire and the Papacy. In: Alois Schmid , Katharina Weigand (Hrsg.): The rulers of Bavaria. 25 historical portraits of Tassilo III. until Ludwig III. Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-48230-9 , pp. 106-117.

- Hermann Nehlsen , Hans-Georg Hermann (Ed.): Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian. Conflicts, setting the course and perception of his rule (= sources and research from the field of history. New series, issue 22). Schöningh, Paderborn et al. 2002, ISBN 3-506-73272-2 . (Collection of essays on important topics; digitized version ).

- Roland Pauler : The German kings and Italy in the 14th century. From Heinrich VII. To Karl IV. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1997, ISBN 3-534-13148-7 , pp. 117ff.

- Alois Schütz: Privy Council and Reich Chancellery as central authorities of the empire under Ludwig the Bavarian (= sources and research from the field of history. New series, issue 23). Schönigh, Paderborn 2005, ISBN 3-506-73273-0 .

- Hermann Otto Schwöbel : The diplomatic struggle between Ludwig the Bavarian and the Roman Curia in the context of the canonical graduation process 1330–1346 (= sources and studies on the constitutional history of the German Empire in the Middle Ages and Modern Times. Vol. 10). Böhlau, Weimar 1968.

- Hubertus Seibert (Ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7954-2757-3 .

- Robert Suckale : The court art of Ludwig of Bavaria. Hirmer, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-7774-5800-7 .

- Heinz Thomas : Ludwig the Bavarian (1282-1347). Emperors and heretics. Pustet, Regensburg 1993, ISBN 3-222-12217-2 (the only scientific biography so far).

Exhibition catalogs

- Peter Wolf et al. (Ed.): Ludwig der Bayer. We are emperors! Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7954-2836-5 (catalog for the state exhibition in Regensburg).

Lexicon article

- Stephan Freund : Ludwig the Bavarian. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 5, Bautz, Herzberg 1993, ISBN 3-88309-043-3 , Sp. 345-352.

- Jürgen Miethke : Ludwig IV. In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie . Volume 21, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1991, pp. 482-487.

- Sigmund Ritter von Riezler : Ludwig the Bavarian . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 19, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1884, pp. 457-476.

- Alois Schütz: Ludwig the Bavarian. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 15, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-428-00196-6 , pp. 334-347 ( digitized version ).

- Michael Straub: Ludwig the Bavarian. In: Large Bavarian biographical encyclopedia. Saur, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-598-11460-5 , Sp. 1216.

- Karl Bosl : Ludwig IV, the Bavarian. In: Biographical dictionary on German history. Edited by Karl Bosl, Günther Franz , Hanns Hubert Hofmann . 2nd completely revised and greatly expanded edition, second volume: I – R. Francke Verlag, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-7720-1082-2 , column 1715-1718.

Web links

- Literature by and about Ludwig IV. In the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Ludwig IV in the German Digital Library

- Ludovicus IV Imperator in the repertory "Historical Sources of the German Middle Ages"

- Publications on Ludwig IV in the Opac of the Regesta Imperii

- Certificate from Emperor Ludwig of Bavaria for the Heilig-Geist-Spital in Nuremberg, digitized version of the image in the photo archive of older original documents from the Philipps University of Marburg

Remarks

- ^ Waldemar Schlögl : Contributions to the youth history of Ludwigs of Bavaria. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 33 (1977), pp. 182-198 ( digitized version ). Heinz Thomas: Ludwig the Bavarian (1282-1347). Emperors and heretics. Regensburg 1993, p. 13. Tobias Appl: Relatives - Neighborhood - Economy. The freedom of action of Ludwig IV on his way to the election of a king. In: Peter Wolf et al. (Ed.): Ludwig der Bayer. We are emperors! Regensburg 2014, pp. 51–57.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347) and Friedrich the beautiful (1314-1330). In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): The German rulers of the Middle Ages. Historical portraits. Munich 2003, pp. 393-407, here: p. 394.

- ↑ Tobias Appl : Kinship - Neighborhood - Economy. The freedom of action of Ludwig IV on his way to the election of a king. In: Peter Wolf et al. (Ed.): Ludwig der Bayer. We are emperors! Regensburg 2014, p. 51–57, here: p. 53. Joseph Gottschalk: Silesian Piastinnen in Southern Germany during the Middle Ages. In: Zeitschrift für Ostforschung 27 (1978), pp. 275-293, here: p. 285. Martin Clauss: Ludwig IV. Der Bayer. Duke, King, Emperor. Regensburg 2014, p. 30. Gabriele Schlütter-Schindler: The women of the dukes. Donations and foundations from the Bavarian duchesses to monasteries and foundations of the duchy and the palatinate from 1077 to 1355. Munich 1999, pp. 64–70 and Bernhard Lübbers : Briga enim principum, que ex nulla causa sumpsit exordium… The battle of Gammelsdorf on 9. November 1313. Historical events and aftermath. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 205–236, here: p. 214. have pointed out that Beatrix came from the Silesia-Schweidnitz line.

- ^ Bernhard Lübbers: Briga enim principum, que ex nulla causa sumpsit exordium… The battle of Gammelsdorf on November 9, 1313. Historical events and aftermath. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 205–236, here: p. 235.

- ^ Claudia Garnier : Staged Politics. Symbolic communication during the reign of Ludwig of Bavaria using the example of alliances and peace agreements. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 169–190, here: p. 176.

- ^ Andreas Kraus : Basics of the history of Bavaria. 2nd, revised and updated edition. Darmstadt 1992, p. 148.

- ^ Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbuch der Deutschen Geschichte 7a). 10th completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, pp. 153–159.

- ^ Claudia Garnier: Staged Politics. Symbolic communication during the reign of Ludwig of Bavaria using the example of alliances and peace agreements. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 169–190, here: p. 177.

- ^ Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbuch der Deutschen Geschichte 7a). 10th completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, p. 159.

- ↑ Mirjam Eisenzimmer: Introduction. In this. (Ed.): Regesten Emperor Ludwig of Bavaria (1314–1347). Organized by archives and libraries. Booklet 10: The documents from the archives and libraries of Franconia I: Administrative districts of Middle and Upper Franconia. Cologne et al. 2015, pp. VII – XLIV, here: pp. XXVII.

- ↑ Markus T. Huber: The appropriation of Ludwig of Bavaria by posterity. Memoria and representation using the example of Munich and the Fürstenfeld Abbey. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 495–525, here: p. 508.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 121.

- ^ On the episodes of Heinz Thomas: Ludwig der Bayer (1282-1347). Emperors and heretics. Regensburg 1993, p. 163ff.

- ^ Alois Schütz: The appellations of Ludwig of Bavaria from the years 1323/24. In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung , Vol. 80 (1972), pp. 71–112.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 124ff.

- ↑ Claudia Garner: The double king. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 269.

- ↑ MGH Const. 6.1 pp. 18-20, No. 29 ( digitized version ). Regesta Imperii , [Regesta Habsburgica 3] No. 1511 ( digitized version ). Claudia Garnier: Staged Politics. Symbolic communication during the reign of Ludwig of Bavaria using the example of alliances and peace agreements. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 169–190, here: p. 182.

- ↑ Claudia Garner: The double king. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 271.

- ↑ Claudia Garner: The double king. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 271.

- ↑ See Gerd Althoff: The peace, alliance and community-creating character of the meal in the early Middle Ages. In: Irmgard Bitsch, Trude Ehlert, Xenja von Ertzdorff (eds.): Eating and drinking in the Middle Ages and modern times. Sigmaringen 1987, pp. 13-25.

- ↑ Claudia Garner: The double king. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 274.

- ↑ MGH Const. 6.1 pp. 72-74, No. 105 ( digitized ). Regesta Imperii , [RI VII], H. 8, No. 107 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Claudia Garner: The double king. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 267.

- ^ Heinz Thomas: Ludwig the Bavarian (1282-1347). Emperors and heretics. Regensburg 1993, p. 172.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347) and Friedrich the beautiful (1314-1330). In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): The German rulers of the Middle Ages. Historical portraits. Munich 2003, pp. 393-407, here: p. 397.

- ^ Roland Pauler: Friedrich the beautiful as guarantor of the rule of Ludwigs of Bavaria in Germany. In: Zeitschrift für Bayerische Landesgeschichte vol. 61 (1998) pp. 645–662, esp. P. 657. Martin Clauss: Ludwig IV. Der Bayer. Duke, King, Emperor. Regensburg 2014, p. 48.

- ↑ Claudia Garner: The double king. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 280. Marie-Luise Heckmann: The double king of Frederick the beautiful and Ludwig of Bavaria (1325 to 1327). Contract, execution and interpretation in the 14th century. In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 109 (2001), pp. 53–81, here: p. 61.

- ^ Claudia Garnier: Staged Politics. Symbolic communication during the reign of Ludwig of Bavaria using the example of alliances and peace agreements. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 169–190, here: p. 186.

- ↑ Claudia Garner: The double king. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 284.

- ↑ Bernd Schneidmüller: Emperor Ludwig IV. Imperial rule and imperial princely consensus. In: Journal for Historical Research 40, 2013, p. 369–392, here: p. 382. Claudia Garner: Der doppelte König. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 288.

- ↑ Claudia Garner: The double king. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 289. Claudia Garnier: Staged Politics. Symbolic communication during the reign of Ludwig of Bavaria using the example of alliances and peace agreements. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 169–190, here: pp. 188ff.

- ↑ Gerald Schwedler: Bavaria and Austria united on the throne. The principle of the whole hand as a constitutional innovation for the double kingship of 1325. In: Hubertus Seibert (Hrsg.): Ludwig der Bayer (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 147–166, here: p. 160.

- ↑ Marie-Luise Heckmann: The double kingship of Frederick the Beautiful and Ludwig of Bavaria (1325 to 1327). Contract, execution and interpretation in the 14th century. In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 109 (2001), pp. 53–81, here: p. 55.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: Ludwig the Bavarian. The last battle between the Empire and the Papacy. In: Alois Schmid, Katharina Weigand (Hrsg.): The rulers of Bavaria. 25 historical portraits of Tassilo III. until Ludwig III. Munich 2001, pp. 106–117, here: p. 112. Hubertus Seibert: Ludwig der Bayer (1314–1347). Empire and Reign in Transition - An Introduction. In the S. (Ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314–1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 11–26, here: p. 13.

- ↑ Claudia Garner: The double king. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 286.

- ^ John Larner: Italy in the Age of Dante and Petrarch, 1216-1380. London et al. 1980, p. 38ff.

- ^ On Henry VII's policy in Italy, cf. William M. Bowsky: Henry VII in Italy. The Conflict of Empire and City-State, 1310-1313. Lincoln, Nebraska 1960.

- ↑ Cf. Fritz Trautz : The imperial power in Italy in the late Middle Ages. In: Heidelberger Jahrbücher 7, 1963, pp. 45–81.

- ^ Roland Pauler: The German kings and Italy in the 14th century. Darmstadt 1997, p. 125ff.

- ↑ Martin Berg: The Italian procession of Ludwig of Bavaria. The itinerary for the years 1327–1330. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries 67 (1987), pp. 142–197 ( online ).

- ↑ Frank Godthardt: Marsilius of Padua and the Romzug Ludwigs of Bavaria. Political Theory and Political Action. Göttingen 2011, pp. 189ff.

- ↑ Jörg Schwarz: Turning away from the papal coronation claim. The imperial coronation of Ludwig of Bavaria and the Roman nobility. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 119–146, here: pp. 125, 130 and 145.

- ↑ Frank Godthardt: Marsilius of Padua and the Romzug Ludwigs of Bavaria. Political Theory and Political Action. Göttingen 2011, pp. 258-264, 264-270.

- ^ Jean-Marie Moeglin: The ideal ruler: Ludwig's empire in a European comparison (1320-1350). In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 97–117, here: p. 108.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Sol iusticie and regis regum vicarius. Ludwig the Bavarian as the "priest of justice". In: Journal for Bavarian State History , Vol. 66 (2003), pp. 795–818, here: p. 808. ( digitized version )

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Sol iusticie and regis regum vicarius. Ludwig the Bavarian as the "priest of justice". In: Journal for Bavarian State History , Vol. 66 (2003), pp. 795–818, especially p. 815. ( digitized version )

- ^ Ludwig Holzfurtner: The Wittelsbacher. State and dynasty in eight centuries. Stuttgart 2005, p. 72f.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 127.

- ↑ Heinz Thomas: Emperor Ludwig's renunciation of Roman royalty. In: Journal for historical research , Vol. 12 (1985), pp. 1-10. Hubertus Seibert: Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and Reign in Transition - An Introduction. In the S. (Ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314–1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 11–26, here: p. 13.

- ↑ Martin Clauss: Ludwig IV. The Bavarian. Duke, King, Emperor. Regensburg 2014, p. 89.

- ↑ Martin Clauss: Ludwig IV. The Bavarian. Duke, King, Emperor. Regensburg 2014, p. 86.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: Europe's Bavarian Years. A sketch of the northeast and west of the empire in the 14th and 15th centuries. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 237–262, here: pp. 238f.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: The Wittelsbach house power expansions in Brandenburg, Tyrol and Holland. In: German Archives for Research into the Middle Ages 61 (2005), pp. 103–159, here: pp. 111–116.

- ^ Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbuch der Deutschen Geschichte 7a). 10th completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, p. 163.

- ↑ Michael Menzel, The Wittelsbach House Power Expansion in Brandenburg, Tyrol and Holland. In: German Archives for Research into the Middle Ages 61 (2005), pp. 103–159, here: pp. 126f., 154.

- ↑ Michael Menzel, The Wittelsbach House Power Expansion in Brandenburg, Tyrol and Holland. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 61 (2005), pp. 103–159, here: p. 126.

- ↑ The dates of life and the number of offspring differ slightly in the family tables: Martin Clauss: Ludwig IV. Der Bayer. Duke, King, Emperor. Regensburg 2014, p. 13. Ludwig Holzfurtner: The Wittelsbacher. State and dynasty in eight centuries. Stuttgart 2005, p. 462f. Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbuch der Deutschen Geschichte 7a). 10th completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, p. 294. Wilhelm Störmer: Ludwig IV. The Bavarian (1314-47). In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Courtyards and residences in the late medieval empire. A dynastic-topographical handbook, Vol. 1: Dynasties and courts. Ostfildern 2003, pp. 295–304, here: pp. 295f. Stefanie Dick: Margarete von Hennegau. In: Amalie Fößel (Ed.): The Empresses of the Middle Ages. Regensburg 2011, pp. 249–270, here: p. 250.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: Europe's Bavarian Years. A sketch of the northeast and west of the empire in the 14th and 15th centuries. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 237–262, here: pp. 245ff.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: Europe's Bavarian Years. A sketch of the northeast and west of the empire in the 14th and 15th centuries. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 237–262, here: pp. 252f.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: Europe's Bavarian Years. A sketch of the northeast and west of the empire in the 14th and 15th centuries. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 237–262, here: p. 249.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: Europe's Bavarian Years. A sketch of the northeast and west of the empire in the 14th and 15th centuries. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 237–262, here: p. 256.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: Europe's Bavarian Years. A sketch of the northeast and west of the empire in the 14th and 15th centuries. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 237–262, here: pp. 253f.

- ↑ Martin Clauss: Ludwig IV. The Bavarian. Duke, King, Emperor. Regensburg 2014, p. 77f. Stefan Weinfurter: Ludwig the Bavarian and his Koblenz program from 1338. In: Nassauische Annalen 123, 2012, pp. 55–79, here: p. 79.