Konradin

Konrad (called Konradin [ ˈkɔnradiːn ]; * March 25, 1252 at Wolfstein Castle near Landshut ; † October 29, 1268 executed in Naples ) was the last legitimate male heir from the Staufer dynasty . He was Duke of Swabia (1254–1268 as Conrad IV. ), King of Jerusalem (1254–1268 as Conrad III. ) And King of Sicily (1254–1258 as Conrad II. ).

The name Konradin common today goes back to the diminutive Corradino , which the Italian vernacular gave it.

Life

Early years

Konradin, the son of Elisabeth von Wittelsbach and the German king Konrad IV. , Was after the death of his father on May 21, 1254 the guardianship of his two unions , the dukes Ludwig II of Bavaria and Heinrich XIII. , assumed. He grew up together with Friedrich of Baden-Austria , who was about the same age and whose father had also died, at the court of Ludwig of Bavaria.

Konradin's Italian inheritance was administered by his uncle Manfred , who was present there , but in 1258, following a rumor about Konradin's death, he himself was crowned King of the Two Sicilies . In addition, Pope Alexander IV urged all feudal people and nobles in the Duchy of Swabia to renounce Konradin in 1255 and forbade support of the Hohenstaufen in the double elections of 1256/1257 . Also Ottokar II. Of Bohemia did not endorse a candidate Conradin. Duke Ludwig of Bavaria finally gave Richard of Cornwall his vote, with the proviso that Konradin could keep the duchy and the Staufer inheritance, and against the payment of 12,000 marks and the hand of a niece of the English king.

Especially in the course of his formal recognition as Duke of Swabia in 1262, the Bishop of Constance Eberhard II gained importance as a further guardian for Konradin . From then on Konradin lived in Meersburg on Lake Constance.

In September 1266 Konradin married Sophia , the eight-year-old daughter of Margrave Dietrich von Landsberg, by procurationem .

Train to Italy

After no way was seen in the empire to help Konradin gain the title of king, his party and Konradin himself concentrated on the Hohenstaufen legacy in southern Italy. There, Charles I of Anjou, with the support of Pope Clement IV, seized power and defeated Manfred of Sicily in the battle of Benevento in 1266 . Therefore, in the late summer of 1267, Konradin moved to Italy with the support of Duke Ludwig II of Bavaria, his stepfather Count Meinhard II of Görz-Tirol , his childhood friend Friedrich of Baden-Austria and others under the goodwill of the Ghibellines . Thereupon Pope Clement IV occupied Konradin on November 18, 1267 with the church ban , since the Holy See was already since the time of Henry VI. felt threatened by the Hohenstaufen rule in southern Italy and wanted to prevent its rebuilding.

Once in Verona , Konradin received further support from the Ghibelline Mastino I della Scala , but the whole undertaking came to a standstill for financial reasons. It was decided to spend the winter in Verona. In the end, Duke Ludwig II of Bavaria and Meinhard II of Gorizia-Tyrol refused to give Konradin any further help and demanded that his debts be settled before their return, which is why Konradin had a large part of his remaining legal and property claims as Duke of Swabia against Duke Ludwig II. had to pledge from Bavaria (so-called Conradin donation ).

Nevertheless, Konradin, accompanied by Friedrich von Baden-Austria and Mastino I della Scala and an army of 3,000 men, set out for southern Italy, crossed Lombardy , which was then predominantly Guelph, and reached Pavia , where he was reinforced again. He came to Rome via Pisa and Siena on July 24, 1268 , where Heinrich of Castile , then Senator of Rome, received him. Despite or because of the opposition to the Pope, Conradin was welcomed in Rome. Henry of Castile reinforced Konradin's army again and also personally joined the train. From Rome, Konradin moved south across the Abruzzo region with an army of about 4,800 men and a baggage train twice as large. The exact destination of the march is not known, but it is believed that it was the Staufer-friendly, rebellious parts of the kingdom. Soon after his invasion of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, his army was defeated on August 23, 1268 in the Battle of Tagliacozzo by the troops of Charles I of Anjou, who had been enfeoffed with Sicily by the Pope.

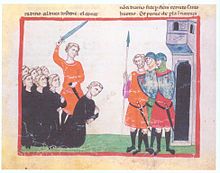

Capture and execution

Although Konradin initially escaped capture, he was picked up by Giovanni Frangipani at Astura and handed over to Charles I of Anjou. He had Konradin publicly beheaded on October 29, 1268 on the Piazza del Mercato in Naples with some companions such as Friedrich von Baden-Austria, Friedrich von Hürnheim , Count Wolfrad von Veringen and his marshal Konrad Kropf von Flüglingen .

It cannot be clearly clarified whether and to what extent a process had previously taken place. It is unclear whether Konradin was released from excommunication before his death. This is contradicted by the fact that Konradin was refused a Christian burial. The corpses were first buried in unconsecrated earth. It was not until ten years later that the bones of Conradin and Frederick were buried in the Christian church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Naples , under the main altar.

Particularly with regard to the history of the reception of this act, it should be emphasized that other prominent members of Konradin's followers were not executed; the most prominent example is Henry of Castile , the senator of Rome.

In the Central State Archive Stuttgart two sides in parchment are preserved on which dated to the anniversary of the death last expression of will, some donations, is held. These papers came to the main state archive via Weingarten Monastery .

Aftermath and reception

The end of the Hohenstaufen

Konradin was the last clearly legitimate heir of the Hohenstaufen in direct male line. But there were illegitimate survivors, i.e. H. Heirs from illegitimate relationships such as Enzio (around 1215-1272), an illegitimate son of Frederick II , the grandfather of Conradin, who was held captive in Bologna until his death , or his cousin Conrad of Antioch , who only died in 1301. Two of his sons were able to hold the office of Archbishop of Palermo until 1320 . The male descendants of King Manfred of Sicily all died in the dungeon of Karl von Anjous or while on the run in insignificance. Manfred's son Heinrich was the last to die in 1318 in prison in Sicily. However, there were still some descendants running through the female Staufer line, and a number of houses trace their ancestry back to them. So Konstanze , the eldest daughter of Manfred of Sicily, married Peter III in 1262 . from the house of Barcelona , who took over the rule of Charles of Anjou in Sicily after the Sicilian Vespers in 1282 and also referred to his Staufer connections. In addition, Margaretha von Staufen married Albrecht the Degenerate and thus joined the Wettin family . Her descendants include the Wettins as electors and dukes of Saxony as well as today's English royal house of the Windsors .

reception

Konradin's failure already received a lot of attention in the Middle Ages. For example, Johannes von Winterthur described that an eagle carried Konradin's blood on its right wings when he was executed, and with this symbolic-mythological image he wanted to point to the injustice and suffering of the event. Martinus Minorita reports in the Chronicle Flores Temporum about the appearance of a false Konradin, who is said to have been a blacksmith from Ochsenfurt , and thus documents the contemporary transfigured longing of the followers for the peacemaking final emperor at the end of the 13th century. This longing was projected onto Konradin as it had previously been projected onto Frederick II, whom his opponents, according to the prophecy of Joachim of Fiore (1132-1202), also saw as the Antichrist . After Konradin's death this expectation was u. a. also transferred to the Wettin Staufer heirs Friedrich the Freidigen of Thuringia . In addition, Konradin's death is mentioned in a number of other chronicles and stories. In the reception, the portrayal of Konradin as the “good young Staufer”, contrasted by Karl von Anjou as his adversary, prevailed in the course of the Staufer myth that was establishing itself.

Giovanni Villani regards the restless reign of Charles of Anjou as a god-sent punishment for his cruel behavior towards Konradin. Johann von Viktring also regards the killing of "iuventutis innocentis" ( the innocent youth ) as cruel. It should be emphasized, however, that in the Kingdom of Sicily, unusually harsh penalties have been imposed in similar cases for a long time, for example by the Staufer Friedrich II; Konradin himself had Charles Marshal executed before the lost battle. Also Dante Alighieri refers in the Divine Comedy on the events in the Kingdom of Sicily at this time, and in particular Manfred of Sicily.

In the 19th century Konradin was understood and received as the bearer of the German national idea, whereby it was emphasized that it was the opponents of the maintenance of the German Empire who murdered him, and the collapse of the Staufer House power and the "splendor of the German Empire" were the consequences of this murder be. This was seen as a milestone in turning away from the long-awaited strong central state. This interpretation was and is becoming increasingly common. a. questioned with reference to the personal dimension of rule in the Middle Ages.

1833 was the then Crown Prince and later King Maximilian II of Bavaria. Of Bertel Thorvaldsen in Rome a 215 centimeter high Konradin sculpture design. After Thorvaldsen's death in 1844, the unfinished marble figure was given to the Bavarian sculptor Peter Schöpf , completed by him and erected in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Naples in 1847. The bones of Konradin, who, because of his place of birth and his Wittelsbach upbringing, was considered to be the bearer of not only the German but also the Bavarian national idea, found their final resting place in the base of the monument. The base inscription reads: “Maximilian Crown Prince of Bavaria erected this monument to a relative of his house, King Conradin, the last of the Hohenstaufen family. In the year 1847 May 14th. "

The last Staufer inspired writers and playwrights in a special way with his tragic fate. Over 100 Konradin dramas and fragments have been known since the 18th century, as well as numerous poems, odes and other lyrical works and prose texts. The poets and authors who have dealt with Konradin are mainly Germans, such as Friedrich Schiller , August Graf von Platen , Gustav Schwab , Conrad Ferdinand Meyer , Agnes Miegel , Theodor Körner , Ludwig Uhland , Benedigte Naubert , Otto Gmelin and Konrad White . The Estonian writer Karl Ristikivi wrote a novel about the fate of Konradin .

In 2000, a memorial plaque was inaugurated in the collegiate church of the Stams Abbey, founded by his mother Elisabeth and her second husband Meinhard II of Görz-Tirol , in memory of Konradin. In 2002 a Staufer stele was inaugurated on the Hohenstaufen on the occasion of his 750th birthday .

meaning

With the failure of Conradin there was no one left who could have promised a personal union of the Kingdom of Sicily and the Holy Roman Empire . This put an end to what the Pope saw as a threat to control over both empires from one source.

Bavaria derived its claim to these areas by pledging the possessions of Konradin in the Upper Palatinate , around Sulzbach-Rosenberg , in southwest Bavaria and Bavarian Swabia to Duke Ludwig II ( donation from the Conradin ).

literature

- Odilo Engels : The Hohenstaufen. 9th, supplemented edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-021363-0 .

- Ferdinand Geldner : Konradin, the victim of a great dream. Greatness, guilt and tragedy of the Hohenstaufen . Meisenbach, Bamberg 1970.

- Knut Görich : The Hohenstaufen. 3rd, updated edition, Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-53593-2 .

- Karl Hampe : History of Konradin von Hohenstaufen . 3. Edition. Köhler Verlag, Leipzig 1942.

- Peter Herd : Corradino di Svevia . In: Enciclopedia Fridericiana 1. Rome 2005, pp. 375-379.

- Peter Herd: The Battle of Tagliacozzo. A historical-topographical study . In: Journal for Bavarian State History . Vol. 25 (1962), pp. 679-744. ( Digitized version )

- Gerald Huber : Konradin, the last Staufer. Games of Power , Regensburg: Pustet 2018, ISBN 978-3-7917-2842-1

- Hartmut Jericke: Konradin's March from Rome to the Palentine Plain in August 1268 . In: Roman historical communications . Vol. 44 (2002), pp. 150-192.

- Walter Migge: The Hohenstaufen in German literature since the 18th century . In: Reiner Haussherr (ed.): The time of the Staufer. History, art, culture . Vol. 3: Articles. Stuttgart 1977, pp. 275-290.

- Kurt Pfister: Konradin. The sinking of the Hohenstaufen . Hugendubel, Munich 1941.

- Hans Schlosser : Corradino sfortunato? Victim of power politics? For the condemnation and execution of the last Hohenstaufen . In: Orazio Condorelli (ed.): Panta rei. Studi dedicati a Manlio Bellomo . Vol. 4. Rome 2004, ISBN 88-7831-174-X , pp. 111-131.

- Klaus Schreiner : The Staufer in legend, legend and prophecy . In: Reiner Haussherr (ed.): The time of the Staufer. History, art, culture . Vol. 3: Articles. Stuttgart 1977, pp. 249-262.

- Hansmartin Schwarzmaier : The world of the Staufer. Way stations of a Swabian royal dynasty . Leinfelden-Echterdingen 2009 ISBN 3-87181-736-8 .

- Günther Schweikle : King Konrad the Young . In: The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . Vol. 5. Berlin / New York, pp. 210-214.

- Andreas Stark: Konradin von Hohenstaufen. The fall of a dynasty 750 years ago. Altnürnberger Landschaft eV 64/2018, [Offenhausen] 2018, ISSN 0569-1451 .

- Eugen Thurnher: Konradin as a poet . In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages . 34: 551-560 (1978). ( Digitized version )

- Hans U. Ullrich: Konradin von Hohenstaufen. The tragedy of Naples . Universitas-Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-8004-1463-5 .

Lexicon article

- Peter Herde : Konradin . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages . Vol. 5. Munich / Zurich 1991, Col. 1368.

- Hans Martin Schaller : Konradin. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 12, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-428-00193-1 , pp. 557-559 ( digitized version ).

- Romedio Schmitz-Esser : Conradin's Italian expedition, 1267/68. In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria . January 16, 2012, accessed February 29, 2012 .

- Eduard Winkelmann : Konradin . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 16, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1882, pp. 567-571.

Web links

- Hans Martin Schaller : Konradin. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 12, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-428-00193-1 , pp. 557-559 ( digitized version ).

- Facsimile of the Minnelieder ascribed to both Konradin in the Codex Manesse of the Heidelberg University Library

Footnotes

- ↑ Amalie Heck: Fateful Paths Baden History. Upper Rhine roads, regional traffic routes and lines of defense in their significance for the regional historical development. Badenia Verlag, Karlsruhe 1996. ISBN 3-7617-0331-7 . Pp. 55-56.

- ↑ Cf. Regesta Imperii V, 1.2, No. 4670a

- ↑ Cf. Regesta Imperii V, 2.3, no.9068

- ↑ Cf. Regesta Imperii V, 2.3, No. 9287

- ↑ Cf. Regesta Imperii V, 1.2, No. 4806b

- ↑ Cf. Regesta Imperii V, 1,2, No. 4840b

- ↑ See Karl Hampe: History of Konradin von Hohenstaufen . 3. Edition. Leipzig 1942, pp. 184f.

- ↑ Cf. Regesta Imperii V, 1,2, No. 4847

- ↑ See Karl Hampe: History of Konradin von Hohenstaufen . 3. Edition. Leipzig 1942, p. 211.

- ↑ See Hartmut Jericke: Konradin's March from Rome to the Palentine Plain in August 1268 . In: Roman historical communications . Vol. 44 (2002), pp. 150-192, here: p. 173.

- ↑ See Hartmut Jericke: Konradin's March from Rome to the Palentine Plain in August 1268 . In: Roman historical communications . Vol. 44 (2002), pp. 150-192, here: p. 192.

- ↑ Cf. Regesta Imperii V, 1.2, No. 4858g

- ↑ Cf. Regesta Imperii V, 1,2, No. 4860a

- ^ August Nitschke: The trial against Konradin. In: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History. Canonical department. Vol. 42 (1956), pp. 25–54 ( digitized version ) explains legal considerations on the death sentence in his article.

- ^ Karl Hampe: History of Konradin von Hohenstaufen . 3. Edition. Leipzig 1942, p. 316 lists a source according to which the absolution "per quosdam Ecclesiae Romanae Cardinales" took place.

- ↑ See Karl Hampe: History of Konradin von Hohenstaufen . 3. Edition. Leipzig 1942, p. 320.

- ↑ Der Thurm von Astura , in: Die Gartenlaube (1878) , Leipzig: Ernst Keil, Heft 25, p. 413. ( Transcription )

- ↑ The role of Konradin's mother Elisabeth von Wittelsbach is unclear here: Cf. Regesta Imperii V, 1,2, no. 4860a

- ↑ Thorsten Schöll: The end of the Hohenstaufen under the sword. In: Südkurier , November 10, 2018.

- ↑ Thorsten Schöll: The end of the Hohenstaufen under the sword. In: Südkurier , November 10, 2018.

- ↑ See MGH SS rer. Germ. NS 3 p.14 and Schreiner, Staufer, p. 253

- ↑ See Klaus Schreiner: Die Staufer in Sage, Legende und Prophetie . In: Reiner Haussherr (ed.): The time of the Staufer. History, art, culture. Vol. 3: Articles. Stuttgart 1977, pp. 249-262, here: p. 253

- ↑ See Klaus Schreiner: Die Staufer in Sage, Legende und Prophetie . In: Reiner Haussherr (ed.): The time of the Staufer. History, art, culture. Vol. 3: Articles. Stuttgart 1977, pp. 249-262, here: p. 251

- ↑ Cf. Knut Görich: Die Staufer. Ruler and empire. Munich 2006, p. 17.

- ↑ Bjarne Jørnæs: The Sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen. Copenhagen 2011, p. 190.

- ↑ Bjarne Jørnæs, pp. 196–197.

- ↑ Hohenstaufen 2002 on stauferstelen.net. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Konrad (IV./II./III.) |

King of Sicily 1254–1258 |

Manfred |

| Konrad (IV./II./III.) |

King of Jerusalem 1254–1268 |

Hugo I. |

| Konrad (IV./II./III.) |

Duke of Swabia 1254–1268 |

Rudolf |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Konradin |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Konradin von Hohenstaufen; Konrad |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Duke of Swabia, titular king of Jerusalem |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 25, 1252 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Wolfstein castle ruins (Isar) |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 29, 1268 |

| Place of death | Naples |