Agnes Miegel

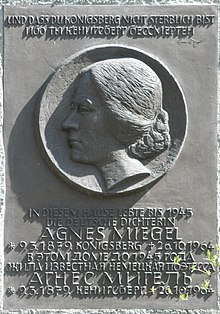

Agnes Miegel (born March 9, 1879 in Königsberg i. Pr. , † October 26, 1964 in Bad Salzuflen ) was a German poet and journalist.

Life

Empire and Weimar Republic

Agnes Miegel's ancestors on her mother's side lived in Filzmoos on the Oberhofgut, the oldest property in the Salzburg region . They were among the exiles from Salzburg who were summoned to East Prussia by Friedrich Wilhelm I (Prussia) in 1732 . She was the only child of the businessman Gustav Adolf Miegel and his wife Helene nee. Hofer.

Miegel attended the high school for girls in Königsberg and then lived from 1894 to 1896 in a boarding school in Weimar , where she wrote her first poems. In 1898 she spent three months in Paris , another study trip took her to Italy. Around 1900 she joined a literary group in Göttingen , which also included Lulu von Strauss and Torney and Börries von Münchhausen . He immediately developed a love affair with Münchhausen, which he ended in 1902 because of the differences in class. Miegel saw Münchhausen as her teacher in everyone, including the artistic field. After the end of the relationship, she saw herself as “the unfortunate creature that led him to sin”.

From 1900 Miegel trained as a pediatric nurse in a Berlin children's hospital and from 1902 to 1904 worked as an educator at the Clifton High School girls' boarding school in Bristol , England . In 1904 she attended the teachers' seminar in Berlin, had to drop out due to illness and in 1905 went to an agricultural school for girls near Munich. She also worked briefly as a journalist in Berlin.

In 1906, Agnes Miegel returned to Königsberg to look after her sick parents and especially her blind father until his death in 1917. From 1920 to 1926 she was the editor of the feature pages of the Ostpreussische Zeitung . She lived in Königsberg until 1945, interrupted by long trips, and worked there as a journalist, author and, from 1927, as a freelance writer.

Together with Hans Leip , Hans Frank , Hans Friedrich Blunck , Wilhelm Scharrelmann and Manfred Hausmann she founded in 1924 in Bremen, the conservative and nationalist -national aligned Autorenvereinigung The Kogge , which in 1934 resolved during the Nazi Gleichschaltung politics and founded in October 1933 Reichsschrifttumskammer with other authors' associations. In general and literary politics, Miegel was also close to the " Wartburg district ". In this union founded by Münchhausen in 1930, National Socialist and National Conservative authors and opponents of the democratic republic came together. He received financial support from the National Socialists. Miegel was one of the enthusiastic supporters of the Nazi movement. For years the authors grouped together in the Wartburgkreis had tried to enforce that German literature should only be regarded as "directed against internationalist, modernist and pacifist tendencies". That is what the Weimar Republic stood for . Miegel represents the "downfall" "like Käthe Kollwitz the beginning of the Weimar Republic", so the literary scholar Angelika Döpper-Henrich.

National Socialism

1933 Miegel after withdrawal and expulsion of Nazi opponents of the Prussian Academy of Arts together with Werner Beumelburg , Hans Friedrich Blunck , Hans Grimm , Hanns Johst , Erwin Guido Kolbenheyer , Borries von Munchhausen , Wilhelm Schäfer , Hermann Stehr and Emil Strauss in their Appointed to the Senate and also made a board member. With the exception of Beumelburg, all of the new senators were members of the Wartburg district.

Also in 1933, as one of 88 German writers, Miegel signed the pledge of loyal allegiance to Adolf Hitler . That year she joined the Nazi women's association. After the death of the Reich President Paul von Hindenburg , she signed the call of the cultural workers for a “ referendum ” because of the merging of the offices of Reich President and Reich Chancellor in the person of Hitler. In 1939 she accepted the Hitler Youth Badge of Honor . In 1940 she became a member of the NSDAP .

Miegel went on lecture and reading tours, received honorary citizenship and was allowed to publish without restrictions. She took an uncritical and supportive stance towards National Socialism and never distanced herself from it. She was enthusiastic about Adolf Hitler . Their attitude becomes clear in the glorifications of Hitler, among others in Karl Hans Bühner's anthology Dem Führer (1938):

“Let

us confess in your hand, Führer, before all the world;

You and we,

never to be separated,

stand for our German country. "

After the attack on Poland , Miegel published her volume of poetry Ostland in 1940 with the verses "[...] Overpowering / humble thanks fills me that I experience this / can still serve you, serving the Germans / with the gift that God gave me!" A turn to blood and soil issues can also be observed. As early as 1934, in a letter to the Nazi writer and cultural politician Hans Friedrich Blunck , she justified why she was not yet a party member, even though she confessed to National Socialism: she considered it, she said, as a "guilt", later as to have connected others to National Socialism. You didn't want to appear as an "occasional hunter". Your confessions - "because I am a National Socialist" - would perhaps have a "more convincing effect on others". "We will", she declared, "be a National Socialist state - or we will not be!" This second possibility, however, would be "the downfall not only of Germany", but "the downfall of the white man."

In 1939 she dedicated a poem to the Reichsfrauenführer Gertrud Scholtz-Klink . The Nazi hereditary and racial ideology can be found in the story The Ransom and other works , as both characters who were for a time exposed to a different culture (here the Tatars ) and their children show changes in their behavior and appearance that Miegel associated with negative connotations .

As a well-known East Prussian homeland poet , she became a "literary figurehead" of the Nazi regime . In 1940 she received the Goethe Prize from the city of Frankfurt am Main, on whose board of directors both Heinrich Himmler and Joseph Goebbels had sat since 1935 . In August 1944, in the final phase of World War II , Hitler added her to the special list of the six most important German writers as an “outstanding national capital” , which released her from all war obligations.

After 1945

In March 1945, she fled to the west with her neighbors and her friend and poet Walter Scheffler from the advancing Red Army . Via Copenhagen they ended up in the Danish refugee camp Oksbøl . In 1946 Agnes Miegel returned to Germany and was accepted into the British zone of occupation in Apelern Castle by the von Münchhausen family. In 1948 she moved to Bad Nenndorf and lived there with her adopted daughter Elise († 1972) until the end of her life.

After 1945, Agnes Miegel remarked on her attitude and her activities under National Socialism: “I have to deal with this alone with my God and with no one else.” Miegel did not distance himself from National Socialism.

Evaluation after 1945

After the end of the Nazi state , Miegels Werke Ostland (Jena 1940) and Werden und Werk were established in the Soviet occupation zone . With contributions by Karl Plenzat (Leipzig 1938) placed on the list of literature to be sorted out.

In the Federal Republic, however, there were numerous honors after 1945. Associations of refugees and displaced persons from the east ("Landsmannschaften") played a prominent role. From the mystification of the East Prussian tradition, Miegel developed a transfigured memory poetry and was thus honored as a figure of identification for expellees. The German Federal Post Office issued a stamp in 1979 as a special stamp for her 100th birthday. In the former home in Bad Nenndorf one as was Agnes Miegel house designated Literature Museum set up dedicated to the namesake. It is operated by the literary Agnes Miegel Society, which is also based there. The street on which the building is located is also named after Miegel. In addition, an Agnes Miegel memorial was erected in a park.

With the distant reassessment that began in the 1990s of people who were important in the Nazi regime and who were honored beyond its end, a negative attitude towards the “cult of remembrance” (Anke Sawahn) also prevailed in the Miegel case.

In the literary stories she got no further than brief remarks. The leading literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki classified Miegel as an author who faithfully paid homage to Hitler (1998, 2014) and assigned her to those who were sponsored by the Nazi regime (1999). Nevertheless, he included three of her poems in his anthology Der Kanon (2005). The Handbuch der Deutschensprachigen Exilliteratur (2013) sees her in the group of authors who “worked with the regime”, while the New German Literature History emphasizes Miegel's poetry, which is laudatory “ Führer poetry”.

After the end of the Nazi regime, a large number of public places (schools, streets, etc.) in West Germany were named after Agnes Miegel. This has now often been withdrawn by the municipal representations because these honors were viewed as inappropriately dealing with National Socialism and those exposed to Nazism.

In 2014, the city of Hanover appointed an advisory board made up of experts to check whether people who gave their names to streets “had active participation in the Nazi regime or serious personal actions against humanity”. He suggested the renaming of the street named after Miegel. The advisory board describes them as "continuously working pillar of the Nazi regime in the journalistic operation of the dictatorship since 1933". With "war-glorifying and anti-Semitic writings" she moved in the "wake of Nazi ideology". After 1945 Miegel did not distance himself. In 2016 the Miegelweg was renamed Igelweg.

In 1968 a memorial stone was erected on the Blumenauer Kirchweg in Wunstorf on the initiative of an acquaintance of the poet. The memorial stone has been dismantled and the street named after her is to be renamed.

Awards and their withdrawal

- 1916: Kleist Prize

- 1924: Honorary doctorate from Albertus University in Königsberg at the Königsberg Kant celebration (1924)

- 1932: Goethe Medal for Art and Science from Reich President Hindenburg

- 1933: Silver rose of the Wartburg district

- 1935: Ring of honor of the General German Language Association

- 1936: First award of the "Agnes-Miegel-Plakette" by the NS cultural community

- 1936: Johann Gottfried von Herder Prize of the FVS Foundation (since 1994 Alfred Toepfer FVS Foundation )

- 1939: Honorary citizenship of the city of Königsberg

- 1939: Literature Prize of the City of Königsberg

- 1939: Schiller Prize, donated and distributed by the Prussian Ministry of Culture (associated with 7,000 Reichsmarks)

- 1939: Gold Medal of Honor of the Hitler Youth as the “greatest living German poet” and for “your successful work for the BDM” by the Reich Youth Leader

- 1939: Badge of Honor of the Hitler Youth

- 1940: Goethe Prize of the City of Frankfurt am Main (combined with RM 10,000), subject to approval by the Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels

- 1954: Honorary citizen of the Bad Nenndorf community

- 1957: Prussian sign of the East Prussian Landsmannschaft

- 1959: Literature Prize of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts

- 1962: Culture Prize of the Landsmannschaft West Prussia

Because of Miegel's NS burden, schools in Düsseldorf-Golzheim, Osnabrück (2010, new namesake: Bertha von Suttner ), Wilhelmshaven (2010, new namesake: Marion Dönhoff ), Willich-Schiefbahn (2008, new namesake: Astrid Lindgren ) were renamed. In 1969 the district council's attempt to rename the Oberschule in Bad Nenndorf to Agnes-Miegel-Gymnasium failed. The supporters came from all parties from the SPD to the NPD and were supported by the Minister of Education. As opponents, pupils (“Action Group for Democratic Pupils”), the majority of teachers and the parents' representatives prevailed.

Roads were renamed in Bielefeld-Sennestadt (2009, new namesake: Nelly Sachs ), Celle (2011, new namesake: Lise Meitner ), Detmold (2009, new namesake: Maria von Maltzan), Erftstadt-Friesheim, Ganderkesee-Elmeloh, Heiden ( Kr.Borken), Lage-Hagen, Lünen-Niederaden (2012, new name: Dohlenweg), Neuenkirchen (Steinfurt district), Osnabrück (2010, new namesake: Bertha von Suttner ), Quickborn-Heide (Kr.Pinneberg), Ratingen ( 2012), Schwerte (2014, new name: Kleine Feld-Straße), Velbert-Neviges and 2016 in Aachen (new name also here: Nelly-Sachs-Straße).

In 2011, the Ardey-Verlag pulled out the memory book Agnes Miegel just one week after it was published . Her life, thinking and poetry from the imperial era to the Nazi era of the editor Marianne Kopp, chairwoman of the Agnes-Miegel-Gesellschaft , back from the trade.

In 1994 a statue of Agnes Miegel created by Ernst Hackländer was inaugurated in the spa gardens of Bad Nenndorf . In 2013, the Bad Nenndorf Council decided to remove the Miegel monument from the spa gardens. At the beginning of 2015, a referendum against its removal from public space, supported by the Agnes Miegel Society, failed. It should also have been important “that the city has been defending itself against annual neo-Nazi marches for a long time. In Bad Nenndorf in particular, such a monument in the spa gardens really has no business ”. In February 2015 the memorial was actually removed from the spa gardens. Since then it has been in the garden of the Agnes Miegel House .

In the city of Ahlen, however, a referendum against the renaming of Agnes-Miegel-Strasse was successful in August 2015. In Sankt Augustin , residents also spoke out against renaming. By resolution of the local city council, an additional legend sign was installed in 2012.

In Wunstorf , the Agnes Miegel memorial stone on the Blumenauer Kirchweg was removed.

Fonts

Miegel was first a poet, then became famous for her form of historical ballad, in which she preferred to thematize love and the fate of women. Further ballads take on legends and fairy tales, a frequent motif is the woman seduced by an elemental being (water or earth). From the 1920s onwards, Miegel turned into a traditional narrator. From the time of National Socialism, her poetry "as an expression of exaggerated love of home [...] the folkish demon after 1933". Her later memory literature in particular painted a glorified picture of East Prussia before the turn of the century, 1900.

- 1901: poems. Cotta, Stuttgart.

- 1907: ballads and songs. Book design by Fritz Helmut Ehmcke . Eugen Diederichs, Jena.

- 1920: poems and games. Eugen Diederichs, Jena

- 1926: home. Songs and ballads. Selected and introduced by Karl Plenzat . H. Eichblatt, Leipzig, 54 pp. (Eichblatt's German Homeland Books, Volume 2/3)

- 1926: Stories from Old Prussia. Eugen Diederichs, Jena.

- 1926: The beautiful Malone. Narrative. Afterword by Karl Plenzat . H. Eichblatt, Leipzig. (Eichblatt's German home books, vol. 1)

- 1927: Games. Dramatic seals. Eugen Diederichs, Jena

- 1927: collected poems. Eugen Diederichs, Jena

- 1928: The resurrection of Cyriacus. (With Die Maar ). Two stories. Edited and introduced by Karl Plenzat . Cover cover picture by Carl Streller . H. Eichblatt, Leipzig. (Eichblatt's German Home Books, Vol. 19)

- 1930: Kinderland. Home and youth memories. Introduced and ed. by Karl Plenzat . H. Eichblatt, Leipzig. 68 p. (Eichblatt's German Home Books, Vol. 47/48)

- 1931: Dorothee. (With returned home ). Two stories. Gräfe and Unzer, Königsberg / Pr. (East Prussia - Books, Vol. 10)

- 1932: Heinrich Wolff . Gräfe and Unzer, Königsberg / Pr. (Picture booklets of the German East, No. 11)

- 1932: The father, stories. Eckhart, Berlin.

- 1932: Herbstgesang, poems. Eugen Diederichs, Jena.

- 1933: Christmas game. Gräfe and Unzer, Königsberg / Pr.

- 1933: Churches in the Order Land - Poems. Gräfe and Unzer, Königsberg / Pr.

- 1933: the father . Three sheets of a book of life. Eckart - Verlag, Berlin - Steglitz 1933 (Der Eckart - Kreis, Vol. 7)

- 1933: The journey of the seven friars . Eugen Diederichs, Jena (German Series, Volume 3)

- 1934: Walk into the twilight - stories. Eugen Diederichs, Jena.

- 1935: The old and the new Königsberg. Gräfe and Unzer, Königsberg / Pr.

- 1935: German ballads. Eugen Diederichs, Jena.

- 1936: Under a bright sky, stories. Eugen Diederichs, Jena.

- 1936: Kathrinchen comes home, stories. Eichblatt, Leipzig.

- 1936: Nora's fate, stories. Gräfe and Unzer, Königsberg / Pr.

- 1937: The amber heart, stories. Reclam, Leipzig.

- 1937: Audhumla, short stories. Gräfe and Unzer, Königsberg / Pr.

- 1937: Herd of the homeland. Stories with drawings by Hans Peters . Gräfe and Unzer, Königsberg / Pr.

- 1938: And the patient humility of the most loyal friends, poetry. Books of the Rose, Langewiesche-Brandt, Ebenhausen .

- 1938: Viktoria, poem and story. Society of Friends of the German Library, Ebenhausen.

- 1939: early poems. (New edition of the poems from 1901). Cotta, Stuttgart.

- 1939: Autumn song. Eugen Diederichs, Jena.

- 1939: The Battle of Rudau, game. Gräfe and Unzer, Königsberg / Pr.

- 1939: autumn evening, story. Private printing, Eisenach.

- 1940: Ostland. Poems. Eugen Diederichs, Jena.

- 1940: In the east wind, stories. Eugen Diederichs, Jena.

- 1940: Whimsical weaving, stories. Langen and Müller, Königsberg / Pr.

- 1940: Order cathedrals. Gräfe and Unzer, Königsberg / Pr.

- 1944: My amber country and my city. Gräfe and Unzer, Königsberg / Pr.

- 1949: But you remain in me, poems. Seifert, Hamelin.

- 1949: The flower of the gods, stories. Eugen Diederichs, Cologne.

- 1951: The shuttlecock, short stories. Eugen Diederichs, Cologne.

- 1951: My own, stories. Eugen Diederichs, Cologne.

- 1952: Selected poems. Eugen Diederichs, Cologne.

- 1952–1955: Collected Works. (GW). Eugen Diederichs, Cologne.

- Vol. 1: Collected Poems.

- Vol. 2: Collected Ballads.

- Vol. 3: Voice of Fate (Stories I).

- Vol. 4: Strange Stories (Stories II).

- Vol. 5: From Home (Stories III).

- Vol. 6: Fairy tales and games.

- 1958: Truso, short stories. Eugen Diederichs, Cologne.

- 1959: My Christmas Book, Poems and Stories. Eugen Diederichs, Cologne.

- 1962: homecoming, stories. Eugen Diederichs, Cologne.

See also

literature

Biographies and individual biographical topics

- Jens Riederer , Marianne Kopp (ed.): When I came to the pension in Weimar ... From letters and memories of Agnes Miegel about her time in the girls' boarding school from 1894 to 1896. Agnes-Miegel-Gesellschaft eV, Bad Nenndorf 2015, ISBN 978 -3-928375-30-6 .

- Marianne Kopp: Agnes Miegel. Life and work . Husum Druck- und Verlagsges., Husum 2004, ISBN 3-89876-116-9 .

- Anni Piorreck: Agnes Miegel. Your life and your poetry . Corrected new edition. Diederichs, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-424-01036-7 .

- Annelise Raub: Miegel, Agnes. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 17, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-428-00198-2 , pp. 471-473 ( digitized version ).

- Ursula Starbatty (ed.): Encounters with Agnes Miegel . Agnes-Miegel-Gesellschaft, Bad Nenndorf 1989, DNB 890820155 (annual edition of the Agnes-Miegel-Gesellschaft 1989/90).

- Jürgen Manthey : The longing for the authoritarian (Agnes Miegel) , in this: Königsberg. History of a world citizenship republic . Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-423-34318-3 , pp. 576-586.

Secondary literature

- Steffen Stadthaus: Agnes Miegel - dubious honor of a National Socialist poet. A reconstruction of their work in the Third Reich and in the post-war period. In: Matthias Frese (Ed.): Questionable honors !? Street names as an instrument of history politics and remembrance culture. Münster 2012, ISBN 978-3-87023-363-1 , pp. 151-178.

- Tilman Fischer: "East Prussia" by Agnes Miegel. In: "Immer Grenzernot und Tänen." Reflection of nationalism in East Prussia in the middle of the 20th century in German literature . Essay at the Internet portal for West Prussia, East Prussia and Pomerania. Dortmund, November 16, 2009.

- Helga Neumann, Manfred Neumann: Agnes Miegel. The honorary doctorate and its history as reflected in contemporary literary criticism . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2000, ISBN 3-8260-1877-X .

- Jurgita Katauskiené: Country and people of the Lithuanians in the work of German writers of the 19th and 20th centuries Jhs. (H. Sudermann, E. Wiechert, A. Miegel and J. Bobrowski) . Verlag Matrica, Vilnius 1997, ISBN 9986-645-04-2 (also dissertation; University of Frankfurt am Main 1997).

- Annelise Raub: Almost like sisters. Agnes Miegel and Annette von Droste-Hülshoff. Outlines of a comparison . Agnes-Miegel-Gesellschaft, Bad Nenndorf 1991, ISBN 3-928375-10-5 (annual edition of the Agnes-Miegel-Gesellschaft 1991).

- Harold Jensen: Agnes Miegel and the fine arts . Rautenberg, Leer 1982, ISBN 3-7921-0261-7 (annual edition of the Agnes-Miegel-Gesellschaft 1982/83).

- Walther Hubatsch: East Prussia's history and landscape in the poetic work of Agnes Miegel . Agnes-Miegel-Gesellschaft, Minden 1978, DNB 800867432 .

- Alfred Podlech (arr.): Agnes-Miegel-Bibliography . Agnes-Miegel-Gesellschaft, Minden 1973, DNB 750830662 (annual edition of the Agnes-Miegel-Gesellschaft 1973).

- Klaus-Dietrich Hoffmann: Agnes Miegel's image of man. With a bibliography. (= Publications of the East German Research Center in the State of North Rhine-Westphalia; Series A. No. 16). East German Research Center in the State of North Rhine-Westphalia, Dortmund 1969, DNB 720280346 (also dissertation; University of Iowa, Iowa City 1967).

- Ruth Pietzner: The nature in the work of Agnes Miegels. (= Rostock studies. Volume 2). Hinstorff, Rostock 1937, DNB 362041857 (also dissertation, University of Rostock).

Web links

- Literature by and about Agnes Miegel in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Agnes Miegel in the German Digital Library

- Information from the Historians' Commission on the website of the City of Münster

- The estate of Agnes Miegel in the German Literature Archive in Marbach

- Website of the Agnes Miegel Society

- Memorial plaque for the ancestors of Agnes Miegel at the Oberhof in Filzmoos (Austria)

- Emancipatory group Bergisch Gladbach, material collection on Agnes Miegel

- Agnes Miegel in the Lexicon of Westphalian Authors

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Gisela Brinker-Gabler, Karola Ludwig, Angela Wöffen: Lexicon of German-speaking women writers 1800–1945. dtv, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-423-03282-0 . P. 220ff.

- ↑ Agnes Miegel to Lulu von Strauss and Torney, letter from January 30, 1903, in: Marianne Kopp, Ulf Diederichs (ed.): When we found each other, sister, how young we were, Agnes Miegel to Lulu von Strauss and Torney. Letters 1901 to 1922. Augsburg 2009, p. 15.

- ↑ a b Agnes Miegel - biography . Agnes-Miegel-Gesellschaft, accessed March 8, 2010.

- ^ Peter Oliver Loew: The literary Danzig - 1793 to 1945: building blocks for a local cultural history. (= Danzig contributions to German studies ). Peter Lang, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften, 2008, p. 136.

- ↑ http://www.vvn-bda-re.de/pdf/Jung.pdf p. 8.

- ↑ Joachim Dyck, Gottfried Benn: A "thoroughbred Jew"? In: Matías Martínez (Ed.): Gottfried Benn. Interplay between biography and work. Göttingen 2007, pp. 113–132, here: p. 119.

- ↑ a b c Angelika Döpper-Henrich: "... it was a deceptive time in between". Writers of the Weimar Republic and their relationship to the socio-political transformations of their time. Kassel 2004, p. 14. (full text)

- ↑ Werner Mittenzwei: The Fall of an Academy or The Mentality of the Eternal German. The influence of the national conservative poets at the Prussian Academy of the Arts 1918 to 1947. Berlin 1992, p. 269.

- ^ Joseph Wulf: Literature and Poetry in the Third Reich. Sigbert Mohn, Gütersloh 1963, DNB 455768994 , pp. 33, 35.

- ↑ List of names in Joseph Wulf: Literature and poetry in the Third Reich. Sigbert Mohn, Gütersloh 1963, DNB 455768994 , p. 96.

- ↑ a b c Ernst Klee : The culture lexicon for the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-10-039326-5 , p. 409.

- ↑ Quoting a poem from Ernst Klee: Das Kulturlexikon zum Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 409, quoted from Bühner's anthology Dem Führer .

- ↑ Volker Koop : Poem for Hitler. Evidence of madness and delusion in the “Third Reich”. be.bra verlag, Berlin 2013, pp. 183–187.

- ↑ According to Meyer's encyclopaedic lexicon , corrected reprint 1981, volume 16, p. 201 “let them occasionally. Recognize blood-and-soil romance; sympathized with the national socialist. Ideas ”.

- ↑ Agnes Miegel and National Socialism. In: muenster.de. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ Eva-Maria Gehler: Female Nazi Affinities. Degree of affinity for the system of women writers in the »Third Reich«. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2010, p. 136 f.

- ^ Arnulf Scriba: Literature during the Nazi regime . LeMO , accessed March 8, 2010.

- ↑ Oliver Rathkolb: Loyal to the Führer and God-Grace. Artist elite in the Third Reich. Österreichischer Bundesverlag, Vienna 1991, ISBN 3-215-07490-7 , p. 173, names p. 176.

- ↑ Agnes Miegel . In: Literaturatlas.de. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ↑ Documented. From the songs of Agnes Miegel. In: young world . Main emphasis. March 19, 2009, p. 3.

- ^ German administration for popular education in the Soviet occupation zone, list of the literature to be sorted out : Transcript letter M, pp. 264–293. Zentralverlag, East Berlin 1946 (see serial no. 7941. Miegel, Agnes […]).

- ^ German administration for popular education in the Soviet occupation zone, list of the literature to be sorted out: Transcript letter M, pp. 186–206. Second supplement, Deutscher Zentralverlag, East Berlin 1948 (see serial no. 5294. Miegel, Agnes […]).

- ^ Andreas Kossert: East Prussia. History and myth. 5th edition. Munich 2007, p. 371.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Agnes Miegel: Identity figure for displaced persons and namesake for schools and streets. In: vvn-bda-re.de. VVN-BdA , accessed in 2020 .

- ^ Working group for the history of the 19th and 20th centuries of the Historical Commission for Lower Saxony and Bremen: Lectures and scientific debate on the topic of “Questionable honors ?! - The reassessment of historical figures and the renaming of streets and prices as a result of debates on the culture of remembrance. ” Newsletter No. 19, May 2014, p. 9.

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki: Literature. You write more sensitively. In: Der Spiegel. March 30, 1998. (spiegel.de) ; Marcel Reich-Ranicki: My History of German Literature. From the Middle Ages to the present. Munich 2014.

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki: My life. Munich 1999.

- ↑ Bettina Bannasch, Gerhild Rochus (ed.): Handbook of German-language exile literature. From Heinrich Heine to Herta Müller. Berlin / Boston 2013, p. 195.

- ↑ Peter J. Brenner : New German Literature History. From “Ackermann” to Günter Grass. 3rd, exp. and revised Edition. Berlin / New York 2011, p. 262.

- ^ Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung. October 2, 2015, p. 18.

- ↑ These ten streets are to be renamed. In: Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung. Online edition. October 2, 2015, accessed October 3, 2015.

- ↑ Renaming: Miegelweg becomes Igelweg. In: New Press . accessed on November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Homeland researcher wants to leave Miegel-Stein in the camp.

- ↑ For this and the following honors see: Schaumburger Nachrichten. Online dossier "Nazi honors in the 3rd Reich", in: sn-online.de ( Memento from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Dirk Fisser: Agnes on the roof and Bertha in the name . ( noz.de [accessed on August 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Persistence rewards . In: Gegenwind - newspaper for work, peace and environmental protection. 251, March 2010, accessed April 14, 2010.

- ↑ Schools. Agnes Miegel School. Spiritual mother. In: Der Spiegel. March 17, 1969. (spiegel.de)

- ↑ Bi: street renaming vs. Historical revision, March 12, 2009, see: de.indymedia.org .

- ^ Celle today, April 8, 2011: celleheute.de ( Memento from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ); see also: Bernhard Strebel (on behalf of the city of Celle), "It doesn't matter what the street you live on is called". Street names in Celle and personal connections with National Socialism, Hanover 2010, see: celle.de .

- ↑ Hans-Heinrich Hausdorf: Salzekurier.de. In: www.salzekurier.de. Retrieved April 9, 2016 .

- ↑ Dohlenweg instead Agnes Miegel Street. In: ruhrnachrichten.de. March 23, 2012.

- ↑ Frank Henrichvark: Agnes Miegel is no longer a role model . In: New Osnabrück Newspaper . May 2, 2009, accessed October 13, 2015.

- ↑ Joachim Dangel Meyer: street name change. The end for Stehr and Miegel. In: Westdeutsche Zeitung. May 11, 2012 ( wz-newsline.de ).

- ↑ WDR Studio Dortmund, November 5, 2014. See: wdr.de .

- ↑ muenster.de

- ^ Website of the city of Aachen, aachen.de

- ↑ VVN-BdA NRW: Untruths about Agnes Miegel. March 13, 2012, see: nrw.vvn-bda.de .

- ↑ Inge Hartmann: Immortal poetry. Agnes Miegel in commemoration - celebration in Bad Nenndorf . In: Ostpreußenblatt . November 19, 1994, p. 6 ( preussische-allgemeine.de [PDF; accessed on December 16, 2019]).

- ↑ Poetry for Hitler: Miegel statue is removed. NDR report from January 11, 2015.

- ↑ Miegel days in the sign of parting. on: sn-online.de

- ↑ Agnes Miegel. In: Homepage of the literary. Agnes-Miegel-Gesellschaft e. V. October 24, 2015, accessed December 16, 2019 .

- ↑ die-glocke.de .

- ↑ Additions to controversial street names have been added. In: General-Anzeiger . October 1, 2012, accessed July 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Günter Niggl, in Handbuch der Deutschen Gegenwartsliteratur , quoted from Gisela Brinker-Gabler, Karola Ludwig, Angela Wöffen: Lexicon of German-language writers 1800–1945. dtv, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-423-03282-0 , p. 220.

- ↑ One of the four stories in this volume, The Journey of the Seven Brothers in the Order , was published in 1933 as a special volume. This book has been reprinted many times, the last time in 2002. The story is reviewed here by Frank Westenfelder.

- ↑ A surviving copy bears a handwritten dedication to the top Nazi propagandist Johann von Leers : "Agnes Miegel, August 19, 1939, Heiligendamm / Doberan"

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Miegel, Agnes |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German writer, journalist and ballad poet |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 9, 1879 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Königsberg (Prussia) |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 26, 1964 |

| Place of death | Bad Salzuflen |