Salzburg exiles

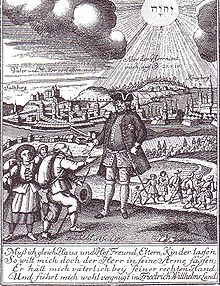

The Salzburg exiles were around 20,000 Protestant religious refugees from the Prince Archbishopric of Salzburg who had to leave their homeland due to a deportation decree of 1731. Most of the exiles were taken in by Prussia .

background

As early as the 1520s, the Reformation had found many followers in the Prince Archbishopric of Salzburg . The Archbishop Matthäus Lang (1519-1540) forbade Protestantism and criminalized his followers. Archbishops Michael von Kuenburg , Johann Jakob von Kuen-Belasy , Georg von Kuenburg , Wolf Dietrich von Raitenau and Markus Sittikus continued the measures against the Protestants as part of the Counter Reformation and recatholicization . Wolf Dietrich expelled them from the entire archbishopric in 1588, but only had resounding success in the city of Salzburg . Only a few secret Protestants lived there around 1600 . There were still numerous secret Protestants among the farmers in Pongau and the miners in the state's salt and ore mines .

There was no persecution during the Thirty Years' War as the Archdiocese focused on foreign policy. Between 1684 and 1690 Max Gandolf von Kuenburg expelled a number of Protestant miners from Dürrnberg and Protestant farmers from the Defereggental of the country.

The authorities were aware of the existence of secret Protestants. Against this, new ordinances were issued, for example by Archbishop Franz Anton von Harrach . His successor Leopold Anton von Firmian tried in 1729 to promote general piety in the country and, advised by his court chancellor Hieronimus Cristani, called the Rallo, Jesuit missionaries to the country, who quickly became aware of the secret Protestants. They (who pretended to be Catholics) were now required to demonstrate their loyalty to the Catholic Church, and some openly confessed persons were immediately expelled in breach of the provisions of the Peace of Westphalia . Therefore the Protestants turned to the Corpus Evangelicorum with a petition . In it they openly professed their Protestant faith. With the help of the Corpus, they wanted to be recognized in the country and have their own Protestant preachers or at least be allowed to emigrate unhindered. The Salzburg government was not ready for recognition. She decided to expel the Protestants as soon as possible so that they could not spread any further. To this end, 6000 imperial soldiers were brought into the country. The Salzburg Protestants coordinated their approach at several meetings. It came on August 5, 1731 in Schwarzach for allegiance of the evangelical Salzburg ( " Schwarzacher salt licks ").

Negotiating emigration

The Archbishop's emigration patent dated October 31, 1731 contradicted the Peace of Westphalia. In the case of Salzburg, expulsion of people of different faiths was not illegal in principle, but its design clearly violated the peace provisions. Instead of at least three years, the dispossessed were granted a withdrawal period of only eight days; The Corpus Evangelicorum therefore met and demanded the amendment of the patent in accordance with the Peace of Westphalia. Initially, the deportation began as planned with the help of the imperial soldiers.

Diplomatic pressure on Salzburg for this approach grew rapidly. Emperor Karl VI. saw Salzburg's actions as a violation of the law. Therefore, the Salzburg government granted some relief. The expulsion of the dispossessed was not ended until March 1732, the property owners were allowed to stay until the end of April 1732. All emigrants were allowed to take their children with them and to sell their houses even after they had left. Even so, the demands of the Peace of Westphalia were not fully met. Under imperial and Prussian pressure, the emigration patent was only replaced in September 1732 by one that fully reflected the peace. At this point the Protestants had already completely left the country.

From 1734 Charles VI. in the so-called Carolinian transmigration, expel another 3,960 Protestants from the neighboring Salzkammergut to Transylvania , which was depopulated by the plague . They did not want to lose any more subjects to Prussia and strengthen the German communities of Neppendorf , Großau and Großpold for possible Turkish incursions.

It was not until 1740, and at the repeated instigation of the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm I , that the surviving emigrants were partially compensated for the loss of the farms, which had to be sold well below price because of the many goods that were also available on the market. The circumstances of the eviction aroused anger across Europe. Especially in Protestant Germany there was a flood of publications on the subject.

Implementation of the emigration

In the late autumn and winter of 1731/32, 4,000 to 5,000 maids and servants were first expelled from the country. The first were captured without warning and taken out of the country. Their distribution in the Protestant regions of southern Germany caused considerable problems.

According to tradition, Friedrich Wilhelm I , King in Prussia , greeted the first arrivals in May 1732 in front of the old Zehlendorf village church with the words:

New sons to me - a mild fatherland to you!

Between May and August 1732, mainly craftsmen and farmers families left the country in 16 organized trains. They moved to Prussia as a group when they were already considered its subjects, which is why their journey was much easier. In 1733 Protestants from Dürrnberg were also brought to Regensburg by ship. Almost a quarter of those deported did not survive the arduous marches in the course of the expulsion.

Settlement in Prussia

On February 2, 1732, Friedrich Wilhelm I issued the Prussian invitation patent for the Salzburg residents. They should settle in East Prussia in order to "repopulate" it , since it had been depopulated by the so-called Great Plague 1708–1714. The first of 66 ships from Stettin arrived in Königsberg on May 28, 1732 . The first of eleven land transports came to Königsberg on August 6, 1732, the last on November 8, 1733. Of the 17,000 immigrants, 377 remained in the city. The active " Salzburg Association " had existed in Königsberg since 1911, and in the 1920s it set up a research center that was initially located in the Prussia Museum and later in the Hintertragheim district.

Most of the people from Salzburg settled in the Gumbinnen area . Poor peasants got a hoof here . Craftsmen could pursue their trade in the cities. In contrast to what is often widespread, the Salzburgers only played a subordinate role in the rétablissement of East Prussia. Most of the farm positions had already been filled by other German immigrants in the 1720s, which is why the Salzburg residents could not be settled as one. Johann Friedrich Breuer , the Lutheran pastor of the Salzburg colony, worked in Stallupönen from 1736 to 1769 .

East Prussian surnames of Salzburg origin (selection)

Aberger, Bleihöfer, Brandstädter, Brindlinger, Degner, Forstreuter, Haasler, Höfert, Hohenegger, Höll, Holle, Höllensteiner, Höllgruber (Hillgruber), Hölzel, Holzinger, Holzlehner, Holzmann, Hopfgärtner, Hörl, Hoyer, Habersatter, Huber, Hundsalz, , Kirschbacher (Kirchbacher), Klinger, Leidreiter, Lürzer, Meyhöfer, Milthaler, Moderegger, Dutch (Niderlehner, Niederlechner), Oberpichler, Pfundtner, Rappolt, Rohrmoser, Schaitreiter, Scharffetter, Schattauer, Schindelmeiser, Schweighofer, Schweinberger, sinn Steincker, Sinnbacher , Turner et al. a.

East Prussian descendants from Salzburg exiles

- Franz Brandstäter (1815–1883), philologist

- Wilhelm Brindlinger (1890–1967), lawyer, politician and writer

- Arthur Degner (1888–1972), painter

- Adalbert Forstreuter (1886–1945), school director and author

- Hans Forstreuter (1890–1978), high school teacher, author and sports teacher

- Hedwig Forstreuter (1890–1967), journalist and writer

- Kurt Forstreuter (1897–1979), archivist and historian

- Walter Forstreuter (1889–1960), CEO of the Gerling Group (1935–1948)

- Fritz Haasler (1863–1948), German surgeon and university professor

- Horst Haasler (1905–1969), lawyer and politician

- Ruprecht Haasler (1936–2017), major general ret. D. of the German Bundeswehr

- Walter Haasler (1885–1976), German author, civil engineer and university professor

- Erich Haslinger (1882–1956), lawyer and entrepreneur

- Bruno Loerzer (1891–1960), Colonel General

- Hans Pfundtner (1881–1945), administrative lawyer

- Günter Rohrmoser (1927–2008), social philosopher

- Franz Sinnhuber (1869–1928), doctor

- George Turner (* 1935), lawyer and science politician

- Agnes Miegel (1879–1964), poet

- Franz Schlegelberger (1876–1970), lawyer

- Hartwig Schlegelberger (1913–1997), politician

Netherlands

After the Dutch envoy had promised favorable conditions, around 780 people, mainly Lutheran miners from the Dürrnberg mine near Hallein and their relatives, set out on their journey to the Netherlands on November 30, 1732. After an arduous journey (ice, storms) they arrived on March 9, 1733 on the island of Cadzand . Since, contrary to promises, they were distributed all over the island and more than one hundred of the emigrants died from a fever epidemic, only 42 families with a total of 216 people decided to stay in the country after improvements had been initiated by the authorities. In the 1970s, a group of the descendants of the exiles interested in history published regular publications on the history of the Salzburg exiles, which are now in the Reich Archives of the Province of Zeeland.

Many of those who left the Netherlands soon after reaching the Netherlands settled in the area around Nuremberg and, thanks to their skills as picture carvers, contributed to the upswing of the Nuremberg toy manufacturers and the industry that developed from them.

America

Under the leadership of the preachers Johann Martin Boltzius and Israel Christian Gronau , a few hundred emigrants found refuge in North America. A good twenty miles northwest of the city of Savannah, Georgia , they founded the Ebenezer settlement. Due to the unhealthy climate, many children of the Salzburg population died in the beginning.

consequences

Until 1772 “convicted” Protestants were expelled from the country. Goethe's Hermann and Dorothea goes back to an episode that was reported in contemporary literature on emigration from Salzburg. For the archbishopric of Salzburg, the high population loss was by the expulsion other than long assumed no catastrophic economic Folgen.Erzbischof Andreas Rohracher asked all 1,966 evangelical Christians to forgiveness for those expulsion of Protestants.

The last Protestants of the Archdiocese of Salzburg were expelled from the Zillertal of the country in 1837 (disregarding the tolerance patent of Emperor Joseph II ) and resettled in the Giant Mountains (Silesia). The main forces behind the expulsion of the Zillertal inclinants were the Archbishop of Salzburg, Prince Schwarzenberg, and the Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I, "the benevolent" .

Remembrance day

August 6 in the Evangelical Name Calendar .

See also

- Deferegger and Dürrnberg exiles

- Joseph Schaitberger

- Transmigration (Austria)

- Friedrich von Görne

- Erhard Ernst von Röder

- Karl Heinrich zu Waldburg

- Salzburg Association (East Prussia)

swell

- Gerhard Gottlieb Günther Göcking : Complete emigration story of those Lutherans who were expelled from the Ertz-Bissthum Saltzburg and mostly accepted into the Kingdom of Prussia . Part I, Frankfurt and Leipzig 1734 ( online ); Part II, Frankfurt and Leipzig 1737 ( online ) - a representation from a Lutheran perspective

- Ludwig Clarus [= Wilhelm Gustav Werner Volk], The emigration of the Protestant-minded Salzburgers in the years 1731 and 1732 , bookstore and book printing company Innsbruck, 1864 digitized - a representation from a Catholic point of view

literature

- Horst-Günter Benkmann : ways and work. Salzburg emigrants and their descendants . 1988.

- Artur Ehmer: The literature on the Salzburg emigration 1731/33. Self-published, Hamburg 1975.

- Gabriele Emrich: The Emigration of the Salzburg Protestants 1731-1732. Imperial law and denominational political aspects . Lit, Münster 2002, ISBN 3-8258-5819-7 .

- Gerhard Florey: History of the Salzburg Protestants and their emigration 1731/1732 . Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Graz 1977, ISBN 3-205-08188-9 .

- Hermann Gollub: Studbook of the East Prussian Salzburg . Susan Ferrill, Dig.

- Charlotte E. Haver: From Salzburg to America. Mobility and Culture of a Group of Religious Emigrants in the 18th Century. (= Studies on Historical Migration Research; Vol. 21) Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2011, ISBN 978-3-506-77105-6

- Christoph Lindenmeyer: rebels, victims, settlers. The expulsion of the Salzburg Protestants . Verlag Anton Pustet , Salzburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-7025-0786-2 .

- Walter Mauerhofer, Reinhard Sessler: For the sake of faith. The expulsion of the Salzburg population . CLV Christian Literature Distribution, Bielefeld 1990, ISBN 3-89397-318-4 .

- Josef Karl Mayr: The Emigration of the Salzburg Protestants from 1731/1732. The game of political forces. In: Communications from the Society for Regional Studies in Salzburg. 69, pp. 1-64 (1929); Vol. 70 (1930), pp. 65-128; Vol. 71 (1931), pp. 129-192. - still relevant, but often confusing, dealing with diplomatic problems.

- Franz Ortner: Reformation, Catholic Reform and Counter-Reformation in the Archbishopric of Salzburg . Pustet, Salzburg 1981. (= Salzburg, Univ., Habil.-Schr., 1981), ISBN 3-7025-0185-1 - most detailed prehistory (16th and 17th centuries).

- Hedwig von Redern : Seeker of Home . Trachsel, Frutigen 1983, ISBN 3-7271-0049-4 - historical tale about the history of the Salzburg exiles.

- Gertraud Schwarz-Oberhummer: The emigration of Gastein Protestants under Archbishop Leopold Anton von Firmian. In: Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde 94th year of association 1954 SS 1–85, Verlag Kiesel, Salzburg 1954 - in somewhat more detailed form as a dissertation from the Leopold Franzens University of Innsbruck to obtain a doctorate in philosophy: Gertraud Oberhummer: The persecution and emigration of Gastein Protestants under Archbishop Leopold Anton von Firmian. Innsbruck 1950.

- George Turner : We'll take home with us. A contribution to the emigration of Salzburg Protestants in 1732, their settlement in East Prussia and their expulsion in 1944/45. 5th revised and expanded edition. Berliner Wissenschaftsverlag, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-8305-3753-3

- George Turner: Salzburg, East Prussia. Integration and identity retention. Berliner Wissenschaftsverlag, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-8305-3787-8

- Mack Walker: The Salzburg trade: expulsion and salvation of the Salzburg Protestants in the 18th century Göttingen 1997, ISBN 3-525-35446-0 . - current standard work on the subject.

- Friederike Zaisberger (Ed.): Reformation, Emigration, Protestants in Salzburg. Exhibition from May 21-26. October 1981, Goldegg-Pongau Castle, State of Salzburg. Salzburger Landesregierung, Salzburg 1981 - Exhibition catalog with short, easily understandable articles as an introduction.

- Wolfgang Splitter: "We ask you to accept this money": Jewish help for the Salzburg and Berchtesgaden emigrants 1732/33 , magazine for religious and intellectual history, vol. 63, no. 4 (2011), pp. 332-347 JSTOR 23898209

- Study on the situation in Württemberg

- Eberhard Fritz: Christian charity or economic calculation? Problems with the admission of Salzburg exiles to the Duchy of Württemberg . In: Leaves for Württemberg Church History. 110/2010, pp. 241-263.

Web links

- "Salzburger Verein", association of the descendants of the Salzburg emigrants

- Private website about the emigrants from Salzburg

- The story of the Salzburg emigrants and other exiles

- Evangelical Church in Salzburg

- Plan of the Neu-Ebenezer housing estate (State and University Library Bremen)

- Salzburg in East Prussia

- Information and exchange list on: Salzburg emigrants · Salzburg emigration from 1731/32

- Salzburg emigrants - contemporary literature until around 1860

Individual evidence

- ^ Gerhard Florey: History of the Salzburg Protestants and their emigration 1731/32. Vienna u. a., 2nd ed. 1986, p. 52.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Ludwig: Mining, Migration and Protestantism. In: Friederike Zaisberger (Ed.): Reformation, Emigration, Protestants in Salzburg. Exhibition May 21–26. October 1981 (Goldegg Castle in Pongau), Salzburg 1981, pp. 38–48, here p. 42.

- ^ Mack Walker: The Salzburg trade. Expulsion and salvation of the Salzburg Protestants in the 18th century. Göttingen 1997, pp. 51-56.

- ^ Josef Karl Mayr: The Emigration of Saltzburg Protestants from 1731/32. The game of political forces. In: Communications from the Society for Regional Studies in Salzburg. 69 (1929), pp. 1-64, here p. 27.

- ^ Josef Karl Mayr: The Emigration of Saltzburg Protestants from 1731/32. The game of political forces. In: Communications from the Society for Regional Studies in Salzburg. 71 (1931), pp. 128-192, here pp. 165f.

- ^ Artur Ehmer: The literature on the Salzburg emigration 1731/33. Hamburg 1975.

- ^ Ship contract Hallein-Regensburg ; Parish archive Dürrnberg: Older parish history, written by GR Josef Lackner 1949-1970 , Volume 1, (Dürrnberg, February 4, 1733), p. 274f. See also: Dürrnberg Protestant persecution

- ^ R. Albinus: Königsberg Lexicon . Wurzburg 2002

- ^ Website of the Salzburg Association , accessed on May 10, 2013

- ↑ Extensive detailed studies on this at Mack Walker: Der Salzburger Handel. Expulsion and salvation of the Salzburg Protestants in the 18th century. Göttingen 1997, pp. 134-171.

- ^ Daniel Heinrich Arnoldt: Brief messages from all preachers who have been admitted to the Lutheran Churches in East Prussia since the Reformation . Verlag Gottlieb Leberecht Hartung, Königsberg / Pr. 1777, p. 116 .

- ^ Hermann Gollub: Studbook of the East Prussian Salzburgers. Gumbinnen 1934. (Reprint: Salzburger Verein e.V., Bielefeld), Familienkunde.at

- ↑ Family name of East Prussian Salzburg residents. In: salzburger.homepage.t-online.de. Salzburg Association, accessed on July 22, 2020 .

- ↑ Description of the holdings. In: archieven.nl. Retrieved July 22, 2020 (Dutch).

- ^ Mack Walker: The Salzburg trade. Expulsion and salvation of the Salzburg Protestants in the 18th century. Göttingen 1997, p. 97f.

- ↑ ORF.at March 14, 2016: Evangelical Church accepts apology from 1966

- ↑ The Salzburg Exulanten in the Ecumenical Saint Lexicon. In: heiligenlexikon.de. Retrieved July 22, 2020 .