Staufer

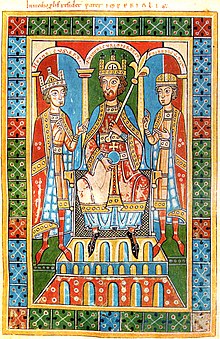

The Staufer (formerly also called Hohenstaufen ) were a noble family that produced several Swabian dukes and Roman-German kings and emperors from the 11th to the 13th centuries . The non-contemporary name Staufer is derived from Hohenstaufen Castle on the Hohenstaufen mountain on the northern edge of the Swabian Alb near Göppingen . The most important rulers from the noble family of the Hohenstaufen were Friedrich I. Barbarossa, Heinrich VI. and Friedrich II.

The beginnings

The earliest Hohenstaufen counts are said to be descended from the Counts of Riesgau , who were called Sigihard and Friedrich. They were in 987 in a document of the later Emperor Otto III. mentioned. Presumably they were related to the Bavarian Sieghardingers .

The name of the first Staufer known by name is known from a genealogical list of the 12th century that Friedrich Barbarossa had made. He was called Friedrich, the leading name of the noble family. All that is known about him is that his sister was married to a Berthold, Gaugraf im Breisgau . The son of this Friedrich, who was also called Friedrich , is mentioned in documents for the middle of the 11th century as Count Palatine in Swabia (1053-1069). From his son Friedrich von Büren , a "Burg Büren" is already known as the manor house, which was probably on the "Bürren" northeast of the village of Wäschenbeuren in what is now the district of Göppingen .

Well-known marriage connections from this generation suggest that the Hohenstaufen were among the most influential aristocratic families in southwest Germany as early as the middle of the 11th century. However, land ownership seems to have been rather low at this point; it was probably limited to areas around Büren and Lorch as well as near Hagenau and in and around Schlettstadt with the Hohenstaufen imperial castle Hohkönigsburg in Alsace .

The first precisely verifiable date in the family history and at the same time an important step in the growth of the importance of the Hohenstaufen to one of the most important noble families of the empire is the year 1079, when the Salian Heinrich IV. , Roman-German king and later emperor, the Hohenstaufen Friedrich I. with enfeoffed the Duchy of Swabia and gave him his daughter Agnes von Waiblingen as his wife.

Friedrich I built Hohenstaufen Castle and founded the Lorch Monastery around 1102 as the family monastery . He and his sons Friedrich II and Konrad III. increased the family's property. At the same time, the Hohenstaufen became important allies of the Salian imperial family in the south-west of the empire . The name Staufer was hardly emphasized by the rulers of this dynasty; the maternal relationship with the Salier emperors was more decisive.

The rise to kingship

After the death of Emperor Heinrich V in 1125, which meant the end of the Salian royal family, Friedrich and Konrad, as the sons of Duke Friedrich I of Swabia and the Salian woman Agnes von Waiblingen, claimed the royal dignity. Friedrich II stood for election, but was defeated by Lothar III. , under whose military leadership Emperor Heinrich V was defeated. Shortly afterwards there was a fight between the new king and the Hohenstaufen over former Salian property , which the family claimed for themselves. In 1127 Konrad, who had also held the title of "Duke of Franconia" since 1116, was proclaimed the opposing king by Swabian and Franconian nobles , but in 1135 had to submit to Lothar.

Crowned Roman-German kings

Conrad III.

After Lothar's death in 1137, Konrad III. In 1138 a Hohenstaufen was elected Roman-German king for the first time. Konrad was able to assert himself against the Guelph Duke Heinrich the Proud , the son-in-law and, through the transfer of the imperial regalia, already designated successor to the deceased emperor.

In the year of his coronation, Konrad demanded that Heinrich renounce one of his two duchies, Bavaria (which the Welfs had held since 1070) or Saxony (which had gone to his son-in-law Heinrich after the death of Lothar). After Heinrich's refusal, he was ostracized on a court day in Würzburg ; both duchies were revoked from him. Bavaria was awarded to the Babenberg Leopold IV of Austria (half-brother of Konrad), Saxony went to the Ascanian Albrecht the Bear . However, Heinrich the Proud was able to maintain his position of power in Saxony until his death (1139) and secure it for his still underage son Heinrich the Lion ; In 1142, Heinrich the Lion was recognized as Duke of Saxony by Konrad, which brought the duchy back into Guelph hands.

The conflict with the Welfs overshadowed Konrad's entire reign and also prevented an early Italian march for the imperial coronation . During these years Europe-wide coalitions were formed in which Konrad reached an alliance with the Byzantine Empire by marrying Bertha von Sulzbach , a sister of his wife, with the Byzantine emperor Manuel I. Komnenos ; the alliance was directed against the Norman kings of Sicily on the one hand, and against the Guelphs on the other. Ultimately, however, this alliance was not successful either in Germany or in Italy. Konrad's coronation as emperor in Rome was also prevented by the (unsuccessful) Second Crusade (1147–1149), which Konrad joined at the urging of Bernhard von Clairvaux , but above all by the subsequent internal political disputes with the Guelphs. Although Konrad was never crowned emperor, he nonetheless carried the title of emperor, presumably to emphasize his equality with the Byzantine emperor.

Even before his participation in the crusade, Konrad had his eldest son Heinrich elected as German king; Heinrich died as early as 1150 at the age of 13. His second son Friedrich was only six years old in 1152. Therefore, shortly before his death, Konrad is said to have appointed his nephew, the later Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa , the son of his older brother, Duke Friedrich II of Swabia, as his successor. To compensate, he appointed the young Friedrich as his successor in the Duchy of Swabia.

In addition to the intensifying dispute with the Guelphs, Konrad's reign was mainly due to a moderate expansion of the Hohenstaufen domestic power and the like. a. as the legal successor of the Counts of Comburg - Rothenburg and shaped by the forging of alliances with numerous territorial rulers (Askanier, Babenberger ). In doing so, however, the Hohenstaufen quickly came up against the territorial limits set by other rulers.

Friedrich I. Barbarossa

After Konrad's death in 1152, Frederick I, known as “Barbarossa”, was elected a king who was trusted to balance the Welfs, to whom he was related on his mother's side, and the Hohenstaufen. In fact, in 1156 an agreement was reached with Heinrich the Lion, who was now Duke of Saxony and Bavaria, from which Austria was separated as an independent duchy under the Babenbergs. In addition, the Guelphs in the north of the empire were assigned a de facto independent sphere of interest. Only when the Guelph was no longer willing to support the ambitious Italian policy of his cousin Barbarossa without consideration did the breakup and in 1180 the dismissal of the powerful Duke of Guelph take place. The beneficiaries, however, were not Barbarossa, but the princes who appropriated the ruined complex of rule of the Guelph.

On his first Italian campaign in 1154/55, Friedrich Barbarossa began a major restoration policy in Italy (Reichstag of Roncaglia , keyword honor imperii ), with which he wanted to withdraw many earlier imperial rights ( regalia ) from the cities. The conflict between the emperor and the pope became increasingly clear. Barbarossa undertook some Italian moves, but with which he largely failed. At this time there was the so-called Alexandrian Pope schism , as the emperor opposed Pope Alexander III, who was elected by the majority of the College of Cardinals . who was considered hostile to the emperor. In the following power struggle, Alexander III. Support for the northern Italian cities striving for autonomy, which joined together in 1167 to form the Lombard League. Barbarossa, who raised several anti- popes, could not achieve his goals militarily, which would have resulted in a subjugation of the cities and greater independence from the papacy, whereby the pope would have had to forego rights in favor of the emperor, so that he in 1177 Peace of Venice Alexander III recognized and shortly thereafter also made peace with the Lombard cities.

However, Friedrich arranged the marriage of his second eldest son Heinrich to the Norman Princess Konstanze of Sicily , the daughter of Rogers II.

Barbarossa achieved some successes in the field of domestic power politics. In 1156, for example, the Palatinate near Rhine under his half-brother Konrad (until 1195) became Hohenstaufen and in Alsace and Swabia (where Frederick's eldest son Friedrich V of Swabia ruled nominally since 1167 ) the Hohenstaufen property was administered centrally. Barbarossa even succeeded in buying the Guelph house in Swabia from Welf VI. to acquire. After 1167, the year of the malaria catastrophe near Rome, Barbarossa succeeded in acquiring some goods from count houses in Swabia that were owed to him and in using his old possessions to build up a relatively closed administrative area in Swabia.

Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa died in 1190 on the Third Crusade in Asia Minor .

Henry VI.

Friedrich's son and successor Heinrich VI. operated a policy that resulted in the unification of the empire with the southern Italian Norman empire ("Unio regni ad imperium"). After a few setbacks, he was able to achieve this in 1194. The Hohenstaufen empire thus extended from the North and Baltic Seas to Sicily. With the capture of Richard the Lionheart he became a fiefdom of England and, thanks to the ransom payments, he financed his successful campaign in Sicily around 1194. However, the inheritance plan he had designed failed .

Because of his sometimes cruel behavior in the Italian policy, Henry VI. sometimes described extremely negatively in historiography. Henry VI. had only one male offspring, which meant a significant narrowing of the family tree of the main Staufer line.

Philip of Swabia

After the death of Henry VI. In 1197 a controversy for the throne began between the Staufer Philip of Swabia and the Guelph Otto IV of Braunschweig . On July 27, 1206 Otto was defeated in the battle of Wassenberg . Philip offered, after successful negotiations with Pope Innocent III. , the vanquished his daughter Beatrix (the elder) for marriage. The coronation of the emperor had already been agreed and was to be announced by the Pope's legates. Philip gathered his army for a final blow against his adversary. However, he left his army to attend the wedding of his niece Beatrix of Burgundy with Otto VII of Andechs in Bamberg. On the day of the wedding, on June 21, 1208, he was stabbed to death in his bedroom by the Bavarian Count Palatine Otto VIII von Wittelsbach . This Count Palatine probably acted out of a motive for revenge. As a member of the Staufer party, he was engaged to one of Philip's daughters. However, this connection was broken under the pretext of being closely related. The exact circumstances of the murder are still unclear. They are discussed as a single perpetrator theory with the motive of a "private revenge" or as a coup d'état involving several princes.

After the murder of Philip and the start of an aggressive Italian policy by Otto IV, who was crowned Emperor of the Empire in 1209 , Pope Innocent III, who had previously supported Otto, called for the election of a new king. So in 1211 Philip's nephew Friedrich II., Who at the death of his father Heinrich VI. was still a minor, elected Roman-German king by a circle of imperial princes who were friendly to the Hohenstaufen .

Friedrich II.

Frederick II , later called "stupor mundi" ("the astonishment of the world") by contemporaries, is considered one of the most important Roman-German emperors of the Middle Ages and is still the subject of numerous scientific and popular representations. He was highly educated, spoke several languages, and showed a lifelong interest in Islam , which did not prevent him from persecuting Christian heretics with all vigor. Growing up under uncertain conditions in the kingdom of Sicily he loved, he moved to Germany in 1212. The south-west of the Staufer fell quickly to him, and Otto IV had to withdraw to the north. The decision in favor of Frederick was not made in Germany, but in France , where in the battle of Bouvines Otto, who was allied with the English king, was defeated by the French king, Philip II, who was allied with Friedrich . Otto died soon afterwards, making Friedrich the unrestricted Roman-German king.

Friedrich was crowned emperor on November 22, 1220, but left Germany to his son Heinrich (VII) and took care of the interests of his Sicilian empire himself. There he centralized the administration, undertook numerous reforms and founded the first state university. He also fought the Saracens in Sicily and, when they were defeated, incorporated them into his bodyguard. A conflict arose with the papacy when Frederick did not immediately embark on the promised crusade and adopted the anti-communal policy of his grandfather Barbarossa. He was thereupon by Pope Gregory IX. banned, but nevertheless traveled to the Holy Land in 1228 , where he reached an armistice without a fight, only through diplomacy, and in Jerusalem himself set the crown of the Kingdom of Jerusalem on his head.

Back in Italy, fighting broke out with papal troops who had invaded the Regnum. Friedrich asserted himself, however, and made peace with the Pope in 1230. He now turned to the problems in Germany, where his son had acted arbitrarily against the sovereigns. Frederick was forced to recognize the rights of the sovereigns by contract in 1232 ( Statutum in favorem principum ; he had already made similar concessions to the clergy prince in 1220), giving up several royal rights. When Heinrich (VII.) Finally rebelled openly, the emperor deposed him in 1235 and had Conrad IV , his second eldest son, elected king in 1237 . The emperor now fought the rebellious Lombard cities. Although he was able to beat them at Cortenuova in 1237 , Friedrich was banned again shortly afterwards by the Pope, who assessed the Staufer's Italian policy as dangerous for the papacy.

The following years were marked by a struggle between empire (emperor) and sacerdotium (pope), in which both universal powers used not only military, but increasingly also propagandistic means and made serious accusations against each other in circulars. Friedrich was called an antichrist , while the emperor accused the pope of only pursuing pure power politics and declared him an antichrist in turn. Friedrich's followers, on the other hand, sometimes apostrophized the emperor as the Messiah . Gregor's successor, actually a Ghibelline (an emerging term for those loyal to the emperor), whose election Friedrich initially supported, continued the hard line. Pope Innocent IV withdrew Friedrich's emperor's dignity in 1245 - a unique incident that was largely received negatively in the world dominated by Catholicism, but nevertheless led to the election of some opposing kings in Germany, which, together with the papal bribery policy, weakened the Hohenstaufen position over time.

Friedrich asserted himself, but died surprisingly on December 13, 1250. The emperor died as a banned man, but his will makes it clear that he was very interested in an understanding with the papacy. It is significant that Frederick II never raised an antipope. Despite all his abilities, Frederick II was not a modern renaissance prince , but a monarch deeply committed to the ideals of the universal Christian empire.

The last Hohenstaufen

After the death of Frederick II in 1250, the Hohenstaufen position of power collapsed, first in Germany and a little later in Italy. In 1251 Conrad IV moved to Italy, where he died in 1254.

In Sicily his half-brother Manfred was able to secure the Hohenstaufen kingship until the battle of Benevento in 1266. Konradin , son of Conrad IV and the last male Staufer in the direct line, suffered a crushing defeat against the knights of Charles of Anjou in the battle of Tagliacozzo on August 23, 1268 . He was publicly executed on October 29, 1268 at the age of 16 on the orders of Charles of Anjou in the Piazza del Mercato in Naples .

In Germany, the interregnum began with the deposition of Frederick II . For the universal empire, the subsequent development meant an extreme weakening, although there were tentative restoration attempts in the late Middle Ages (see above all Henry VII.) And the emperors at least formally adhered to the basic concept of universal rule until the end of the Middle Ages. After the Interregnum, the Habsburgs established themselves with Rudolf von Habsburg as the new royal dynasty, with the Luxembourgers - sometimes very successfully - competing with the Habsburgs from the early 14th century to the early 15th century .

reception

Especially since the time of humanism , the end of the last Staufer Konradin was not only taken up by scholars.

After the German Empire was founded in 1871, the Staufer myth was revived. So Emperor Wilhelm I was occasionally called Barbablanca ("white beard"), analogous to Barbarossa ("red beard"). Wilhelm I as the finisher of Friedrich I Barbarossa - this idea was implemented in its purest form in the Kyffhäuser Monument in 1896 . According to legend, Barbarossa slept down in the Kyffhäuserberg only to wake up one day and save the empire.

In 1968 the Society for Staufer History was founded in Göppingen to promote research, dissemination and communication of knowledge about the Staufer people.

In 1977, on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the state of Baden-Wuerttemberg , the Stuttgart State Museum organized the exhibition "Zeit der Staufer", one of the first major history shows in post-war Germany. In the same year the street of the Staufer was established, a tourist route along the historical sites in the former heartland of the Staufer. Since 1977, the Prime Minister of Baden-Württemberg has been awarding a Staufer Medal to people who have made special contributions to the state.

The masterpiece of Hohenstaufen architecture and aesthetics, the Castel del Monte , has been recognized as the cultural heritage of Italy on the reverse of the Italian 1 cent coin since 2002 . In the same year, the painter Hans Kloss completed a 30-meter-long and 4.5-meter-high Staufer circular painting in Lorch Abbey , which depicts the history of the Staufer from 1102 to 1268.

From September 19, 2010 to February 20, 2011, the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museums Mannheim showed the exhibition of the states of Baden-Württemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate and Hesse Die Staufer and Italy .

The city of Schwäbisch Gmünd adorns itself with the title “Oldest Staufer City ”. On the occasion of the Staufer Festival for the 850th anniversary of the city in July 2012, the specially written stage work Die Staufersaga was performed, which depicts the history of the Staufer family.

Since 2001, the Staufer Friends Committee has erected over thirty Staufer steles in Germany, France, Italy, Austria and the Czech Republic .

Frederick II is still venerated in southern Italy today. There are almost always fresh flowers on his porphyry sarcophagus in the Cathedral of Palermo .

Kyffhäuser Monument (1896) with Wilhelm I (above) and Friedrich I (below)

Italian 1 cent coin (2002) with Castel del Monte

Staufer round picture by Hans Kloss (detail, 2002)

Tourist information sign from Schwäbisch Gmünd (2012)

Staufer stele in Cheb , Czech Republic (2013)

Flowers at the tomb of Frederick II in the Cathedral of Palermo (2014)

Important Staufer

- Conrad III. , Roman-German king 1138–1152

- Friedrich I. Barbarossa , Roman-German king 1152–1190, emperor from 1155

- Konrad der Staufer , Count Palatine of the Rhine 1156–1195

- Henry VI. , Roman-German King 1169–1197, Emperor from 1191, King of Sicily 1194–1197

- Philip of Swabia , Roman-German King 1198–1208

- Friedrich II. , King of Sicily 1198–1250, Roman-German King 1212–1250, Emperor from 1220

- Conrad IV. , Roman-German King 1237–1254, King of Sicily 1250–1254

- Manfred , King of Sicily 1254–1266

- Konradin , the last Staufer in the direct male line

See also

literature

Overview works

- Odilo Engels : The Hohenstaufen. 9th supplemented edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-021363-0 . (1st edition from 1972).

- Odilo Engels: Staufer Studies. Contributions to the history of the Hohenstaufen in the 12th century. Celebration for his 60th birthday. Edited by Erich Meuthen and Stefan Weinfurter . Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1988, ISBN 3-7995-7060-8 (2nd modified and expanded edition, ibid 1996).

- Knut Görich : The Hohenstaufen. Ruler and empire. 3rd updated edition, Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-53593-2 .

- Reiner Haussherr (ed.): The time of the Staufer. History, art, culture. 5 volumes. Cantz, Stuttgart 1977-1979.

- Werner Hechberger : Staufer and Welfen 1125–1190. On the use of theories in historical science (= Passau historical research. Vol. 10). Böhlau, Cologne et al. 1996, ISBN 3-412-16895-5 (refutation of the theory of a basic Staufer-Welf antagonism).

- Werner Hechberger, Florian Schuller (eds.): Staufer & Welfen. Two rival dynasties in the High Middle Ages. Pustet, Regensburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-7917-2168-2 . ( Review )

- Hans Martin Schaller : Staufer time. Selected essays (= Monumenta Germaniae Historica Schriften. Vol. 38). Hahn, Hannover 1993, ISBN 3-7752-5438-2 .

- Hansmartin Schwarzmaier : The world of the Staufer. Way stations of a Swabian royal dynasty. Library of Swabian History. Leinfelden-Echterdingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-87181-736-6 .

- Hubertus Seibert , Jürgen Dendorfer (Ed.): Counts, dukes, kings. The rise of the early Hohenstaufen and the empire (1079–1152). (= Medieval research. Vol. 18). Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2005, ISBN 3-7995-4269-8 ( digitized version ).

- Wolfgang Stürner : The Staufer. Volume 1: Rise and Power Development (975–1190). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2020, ISBN 978-3-17-022590-9 .

- Wolfgang Stürner: Thirteenth Century. 1198–1273- (= Gebhardt. Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte . Vol. 6). 10th, completely revised edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 3-608-60006-X .

- Stefan Weinfurter: Stauferreich in transition. Concepts of order and politics in the time of Friedrich Barbarossa. (= Medieval research. Vol. 9). Thorbecke, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-7995-4260-4 ( digitized version ).

Biographies

- Peter Csendes : Heinrich VI. (= Design of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance ). Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1993, ISBN 3-534-10046-8 .

- Peter Csendes: Philipp von Schwaben. A Staufer in the struggle for power. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-89678-458-7 .

- Knut Görich: Friedrich Barbarossa. A biography. CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-59823-4 .

- Hubert Houben : Emperor Friedrich II. (1194-1250). Rulers, people and myths (= Kohlhammer-Urban pocket books. Vol. 618). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-17-018683-5 .

- Bernd Ulrich Hucker : Emperor Otto IV. (= Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Writings. 34). Hahn, Hannover 1990, ISBN 3-7752-5162-6 .

- Johannes Laudage : Friedrich Barbarossa. (1152-1190). A biography. Edited by Lars Hageneier and Matthias Schrör . Pustet, Regensburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-7917-2167-5 .

- Ferdinand Opll : Friedrich Barbarossa. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1990, ISBN 3-534-04131-3 .

- Wolfgang Stürner: Friedrich II. (= Shaping the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. ). 2 volumes. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1992–2000;

- Vol. 1: The royal rule in Sicily and Germany 1194-1220. 1992, ISBN 3-534-04136-4 , review ;

- Vol. 2: The Emperor 1220-1250. 2000, ISBN 3-534-12229-1 , review .

Conference proceedings

- Bernd Schneidmüller , Stefan Weinfurter and Alfried Wieczorek (eds.): Metamorphoses of the Staufer Empire. Theiss, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8062-2365-1 .

Web links

- "The Staufer and Italy" - Exhibition of the states of Baden-Württemberg , Rhineland-Palatinate and Hesse 2010

- The world of the Hohenstaufen . Der Spiegel special issue, issue 4, 2010; Detailed overview of contents

Remarks

- ↑ Lexicon of the Middle Ages , Vol. 8, Col. 76–79.

- ↑ Cf. for example Knut Görich: Friedrich Barbarossa: Eine Biographie . Munich 2011, p. 32f.

- ↑ Knut Görich: The Staufer. Ruler and empire. Munich 2006, p. 119.

- ↑ a b Round Staufer image in Lorch Abbey (description on Hans Kloss website)

- ↑ Origin meets future , on staufersaga.de, accessed on July 20, 2019

- ↑ a b What is a Staufer stele? , on stauferstelen.net (with interactive maps), accessed on December 13, 2013.

- ^ Hubert Houben: Kaiser Friedrich II. (1194-1250). Ruler, man, myth. Stuttgart 2008, p. 9.