Bernhard of Clairvaux

Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (* around 1090 at Fontaine-lès-Dijon Castle near Dijon , † August 20, 1153 in Clairvaux near Troyes ), Latinized Sanctus Bernardus , was a medieval abbot , crusade preacher , church teacher and early Scholastic mystic . He is considered to be one of the most important monks of the Cistercian order , for whose spread across Europe he was responsible.

Live and act

Bernhard was the third son of the knight Tescelin le Roux (the red-blonde) and his wife Aleth from the Montbard family . His siblings were Guido, Gerhard, Andreas, Bartholomäus, Nivard and Humbelina . He received his education in Châtillon-sur-Seine .

In 1112 (after some 1113) Bernhard and about 30 relatives and friends, including four biological brothers, entered the Cîteaux monastery south of Dijon , founded in 1098 , from which the name of the Cistercians is derived: the Latin cistercium is Cîteaux, German in French Cisterce. Two years after joining the company he was sent to the Western Champagne the Clairvaux to establish ( 1115 ), the first abbot, he was. His biographer and brother Wilhelm von Saint-Thierry reports in the Vita Prima of a liturgy of a priestly and abbot ordination of Bernhard by the learned Bishop of Chalons, Wilhelm von Champeaux . They became good friends afterwards.

Abbot Bernhard's Clairvaux, a primary abbey of the Cistercian order, initiated a renewal of the monastic community life, which was also expressed in monastic architecture. This art, so Georges Duby , owes everything to St. Bernhard, it is inextricably linked with the ethics that Bernhard embodied and that he wanted to convey to the world by all means.

The Cistercian order distinguished itself from the life of the monks in the Benedictine monastery of Cluny . In the monasteries of the Cistercians the Regula Benedicti of St. Benedict of Nursia interpreted literally and ascetically. Bernhard is not the founder of the Cistercians, but he was decisive for the rapid expansion of the order, which is why he is venerated as the greatest saint of the order alongside the three founding abbots of the order - ( Robert von Molesme , Alberich von Cîteaux and Stephan Harding ).

Role in ecclesiastical and secular diplomacy

Bernhard dealt in detail with the papal schism between Innocent II and Anaclet II , where he advocated Innocent II, who was generally recognized in reform circles. Bernhard is also said to have won King Henry I of England for Innocent II - as his vita reports . For Bernhard, the founding of a subsidiary monastery in England, which he had planned and which took place in Rievaulx in 1132, played an important role in this negotiation .

Bernhard received Innocent II in Clairvaux in 1131, and the Pope and his companions admired the brothers' poverty and humility. The abbot subsequently traveled to Aquitaine to win Duke Wilhelm X for Innocent II. In February 1132, Stephan Harding and a week later Bernhard were given particularly coveted exemption privileges for the order.

On his travels, Bernhard tried hard to win over more monks for monastic life. From a trip to northern France in 1131, for example, he brought 30 educated men of distinguished origin back to Clairvaux. Bernhard's convent grew to an estimated total of around 200 monks and 500 conversations during his lifetime.

In 1133 he accompanied Pope Innocent II on his journey to Italy. He was active on behalf of the Pope in the talks between Genoa and Pisa, which were previously attached to the antipope Anaclet II. Bernhard was so successful as a diplomat that he was offered the bishopric of Genoa ; however, he rejected the episcopate. On his return to France, Pope Innocent II commissioned him to decide the controversial archbishopric in Tours .

Crusades

With his sermons he sparked a storm of enthusiasm for the Crusades across Europe. He advertised them in northern France , in Flanders , on the Rhine and on the Main. In Bernhard's time, the idea of the crusade no longer only related to the defense of Jerusalem and the crusader states , but was now also applied to goals in Europe. Bernhard's Letter 457 from 1147, in which he called for a crusade against the Wends , is perhaps the most famous call for religious war; According to Dieter Hehl, Bernhard was "probably the first to give the idea of a violent mission a place in the history of the crusade". In the letter, Bernhard emphasizes the forgiveness of sins as a reward for participating in a religious war, even if it is not considered a crusade. The text can be seen as a turning point in the theology of just defense war. In Bernhard's time, the church teaching office came to the conclusion that war could not be opened simply because of the non-Christianity of the enemy.

On behalf of Pope Eugene III. , the first Cistercian Pope, Bernhard was successful in bringing about the second crusade (1147 to 1149). At Christmas 1146, Bernhard achieved that the German King Konrad III. as well as his Guelf opponent Welf VI. agreed to participate in the crusade. In his eulogy for the Knights Templar , he denounced secular knighthood as corrupt and pleaded for a spiritual knighthood that he wanted to see realized among the Templars.

Bernhard understood the knightly ideal of the Crusades, dying for the Lord, as a high merit. He resolutely stood up for the "spiritual soldiers", the Knights Templar. In his letter to this knightly order, he gives a theological justification for religiously motivated arms deals and at the same time warns them against excesses and vices in military service.

Episcopal appointments rejected

Bernhard is often shown with the bishop's miter at his feet, which he has rejected. At the end of 1130, Bernhard was elected bishop for the first time in Châlons-sur-Marne .

Overall, he rejected the episcopate five times: in Châlons (around 1130), Genoa (1133), Milan (1135), Langres (1138) and Reims (1139). In the latter case, King Ludwig VII even asked Bernhard to answer the call of the cathedral chapter, but Bernhard refused because he was neither physically nor physically capable of doing so.

The quarrel with Abelard

Bernhard's argument with Petrus Abelard is considered to be one of the most violent theological arguments of the 12th century. Bernhard called the speculative-discursive theology of Abelard stultilogia (roughly “doctrine of gates” from Latin stultus = “stupid”, as noun: “the gate”); the abbot of Clairvaux represented rather the theology of practical appropriation and prayerful realization. There should have been a public argument between Bernhard and Abelard in May 1141 before bishops and theologians to find a decision, but on the eve of this disputation Bernhard obtained a condemnation of Abelard's tenets by the bishops present. As a friar of Bernhard and a student of Abelard, Otto von Freising later criticized Bernhard's actions because the Abbot of Clairvaux had acted mercilessly against Abelard. The quarreling theologians were reconciled before death.

Adoration

Bernard of Clairvaux was canonized in 1174 ; his feast day is August 20th. Among other things, he is the patron saint of monastic vocations , preachers and beekeepers . In 1830 he was appointed Doctor of the Church . He appears in Dante's Divine Comedy and Goethe's Faust . Bernhard von Clairvaux was highly valued by Martin Luther , who wrote about him: "If there has ever been a godly and pious monk, it was St. Bernhard, whom I alone hold much higher than all monks and priests on the whole earth." Bernhards emphasized Of course, Luther addressed loyalty to the Pope less; What Protestants like about Bernhard are his approach to reform and his emphasis on gospel simplicity. For these and similar reasons, Bernhard's memorial day on August 20 is also included in the calendar of names of the Evangelical Church in Germany , the Missouri Synod of the Lutheran Church , the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and the Anglican Church . Pope Pius XII dedicated the encyclical Doctor mellifluus to the saint on May 24, 1953, on the 800th anniversary of his death . For centuries, Bernhard has been called the “Last Church Father” because his writings were written in the style of the great church fathers, geared towards the whole of Christian existence and emerged from a liturgical context.

Representations

He is represented with a staff , bible , miter , passion instruments or beehive , dressed in a white monk's habit with a cowl . The beehive is a reference to his honey-flowing sermons and has only appeared since the 16th century. Medieval representations in manuscripts and church windows show him with the miter at his feet, as a reference to the repeatedly rejected bishop appointments. Bernhard is often depicted with the Virgin Mary. Because of his visions of Mary, artists portray him looking up at her or helping him to write. Another Marian motif, the lactatio , refers to the wetting of Bernhard's lips with Mary's breast milk; this helps him to his eloquence. Finally, one knows depictions of Bernhard embracing Christ crucified; Although this amplexus motif is based on medieval tradition, it did not appear as an artistic motif until the 15th century and was widely used in the baroque era. However, there are also earlier depictions of the motif. Representations with a dog at his feet refer to the legend that his mother saw him in a vision before he was born as a little white dog with a reddish back, which was interpreted as follows: she carried the future “watchdog of God” under her heart.

Theological meaning

His works were very widespread - 1,500 manuscripts are known today - and have been translated and eagerly read at all times. One of his most famous writings is the letter to his former pupil, which goes by the name of Eugene III. became Pope. Bernhard was fatherly towards the Pope, but also critical. He exhorts him not to conform to the flattery and material prosperity of the papal court. The letter, widely known as De consideratione , is frequently reprinted and quoted today.

Bernhard is considered the founder and pioneer of the medieval Christ mysticism, the Christ devotion. At the center of his mysticism is Jesus as the crucified, as a man of suffering. Bernhard's work had a lasting influence on piety over the next few centuries, including Protestantism. Until recently he has been ascribed the lyric text to which Salve caput cruentatum belongs, which Paul Gerhardt O Haupt wrote after, full of blood and wounds . However, the author was a different Cistercian, Arnulf von Löwen , who had emerged from the Bernhardin tradition. The devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus is rooted in the Bernardine doctrine and was deepened by the Cistercian nuns of the Helfta Monastery .

In addition, Bernhard is considered Doctor marianus , one of the great mariologists of the Middle Ages. In sermons and letters he dealt with the motherhood of Mary, the Marian figure in the Proto-Gospel (Gen 3:15), the Immaculate Heart of Mary, the Annunciation to Mary and her Ascension; preoccupation with the Virgin Mary was widespread among the early Cistercians. Bernhard took a controversial position on the question of Mary's Immaculate Conception . Bernhard also appears as a Mariologist in the final scene of Goethe's Faust . As a chivalrous young man with poetic talent, he wanted to pay homage to the Virgin Mary spiritually. His Marian sermons are now valued as masterpieces of Marian devotion. The last verse of the Antiphon Salve Regina is said to come from Bernhard's pen.

Last but not least, Bernhard's understanding of aesthetics is praised. He advocated purity of style in music and architecture, which significantly influenced the history of Western architecture. Since all church buildings of the Cistercians should have the same dimensions, one spoke of a Bernhardine plan after Bernhard's architectural reform . The simplicity of the Cistercian buildings is seen as a component of the entire reform program; the churches of the first centuries are mainly famous for the dramatic light.

On behalf of the General Chapter, Bernhard was given an overview of the so-called “second” Cistercian reform of Gregorian chant . The first reform was made by St. Stephan Harding carried out. From 1148 to 1153, Bernhard and his colleagues created new versions of the liturgical chant based on criteria of originality and beauty. This choral reform in turn influenced the young Dominican order .

literature

Works

- MS-B-183 - Hugo de Balma. Jan van Ruusbroec. Bernardus Claraevallensis. Augustine (theological collective manuscript). Rhineland (Cologne?) Around 1440–1450. Digitized

- MS-B-176 - Gerardus de Zutphania. Bonaventure. Johannes de Schonhavia. Petrus de Alliaco. David de Augusta. Gerlacus Petri. Johannes Cassianus. Bernardus Claraevallensis et alia ( composite manuscript). Eastern Netherlands [15. 3rd quarter]. ( Digitized version )

- MS-C-16 - Gesta trium regum. Bernardus Claraevallensis. Jacobus de Marchia. Vita prima sancti Bernardi abbatis et alia. (Composite manuscript) . Kentrop, Cistercian Abbey, around 1467 ( digitized version )

- Speculum de honestate vitae. Attached works: Octo puncta perfectionis assequendae. Ulrich Zell, Cologne around 1473. ( digitized version )

- MS-B-208 - Sermones (oral). Lower Rhine 1478. ( digitized version )

- MS-B-203 - (Ps .-) Anselmus Cantuariensis. Bonaventure. (Ps .-) Augustine. (Ps .-) Bernardus Claraevallensis. Arnulfus de Boeriis. Petrus de Alliaco (theological collective manuscript). Kreuzherrenkonvent (?), Düsseldorf around 1508. ( digitized version )

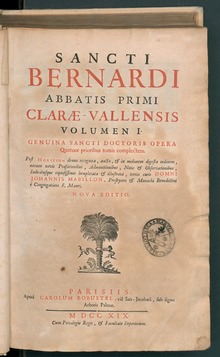

- Opera omnia in six books (in 2 volumes), edited and annotated by Jean Mabillon, Paris 1690.

- Complete works , 10 vols., Ed. v. Gerhard B. Winkler ; Tyrolia: Innsbruck 1990, ISBN 3-7022-1732-0 .

- Bernardin Schellenberger (Ed.): Bernhard von Clairvaux. Return to God. The mystical writings , Düsseldorf 2006.

Secondary literature

- Günther Binding : Bernhard von Clairvaux . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 1, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7608-8901-8 , Sp. 1992–1997.

- Adriaan H. Bredero: Bernhard von Clairvaux. Between cult and history; about his vita and its historical evaluation. From the Dutch by Ad Pistorius. With a foreword by Ulrich Köpf, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-515-06898-8 .

- Peter Dinzelbacher : Bernhard von Clairvaux; Life and work of the famous Cistercian . Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2012, ISBN 978-3-86312-310-9 .

- Gillian R. Evans: Bernard of Clairvaux . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, ISBN 0-19-512525-8 .

- Wilhelm Hiss: The anthropology of Bernhard von Clairvaux. De Gruyter, Berlin 1964 (= sources and studies on the history of philosophy. Volume 7).

- Jean Leclercq: Art. Bernhard von Clairvaux . In: Theological Real Encyclopedia . Volume 5, Berlin 1980, pp. 644-651.

- Jean Leclercq: Bernhard von Clairvaux. Mystic and man of action. Neue Stadt, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-87996-782-7 .

- Ulrich Köpf: Bernhard von Clairvaux . In: Hans Dieter Betz (Hrsg.): Religion in past and present . Volume 1, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-16-146949-7 , Sp. 1328-1331.

- Hartmut Sommer: Bridegroom of the Soul. The stations in life of Bernhard von Clairvaux in Burgundy. In: The great mystics. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2008, ISBN 978-3-534-20098-6 .

- Bernhard Vošicky : Bernhard about Bernhard. Spiritual teachings of St. Bernard of Clairvaux. Be & Be Verlag, Heiligenkreuz im Wienerwald 2008, ISBN 978-3-9519898-4-6 .

- Gerhard Wehr : Bernhard von Clairvaux . Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-86539-287-9 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Bernhard von Clairvaux in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Bernhard von Clairvaux in the German Digital Library

- Database of all medieval representations by Bernhard

Works

- Opera omnia Sancti Bernardi Claraevallensis , works based on Patrologia Latina 182–185

- Sermones sancti Bernardi abba - // tis clareuallis super Ca [n] tica ca [n] tico [rum] . Flach, Strasbourg 1497. Digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Homiliae super evangelio Missus est angelus Gabriel . Printer of pseudo-Augustine, De fide (= Johann Solidi ?; GW 2953), Cologne to 1473. urn : NBN: de: hbz: 061: 1-96292 }

- Speculum de honestate vitae . Martin Flach, Basel around 1472/74 ( digitized edition )

- De planctu B. Mariae Virginis . Ulrich Zell, Cologne around 1470. Digitized edition

- Meditationes de interiori homine . Johann Amerbach, Basel 1492 ( digitized version )

- Opuscula (Cologne around 1478) ( digitized version )

- Sermons de tempore et de sanctis et de diversis . Nikolaus Keßler, Basel 1495 ( digitized version )

- Sermons de tempore et de sanctis et de diversis . Peter Drach, Speyer after 1481 ( digitized version )

- Digitized manuscript: Commentary on the Canticum canticorum. De libero arbitrio. Passio Margaretae of the Bamberg State Library

-

Works at archive.org, including:

- Saint Bernard On consideration , engl. Translated by George Lewis, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1908.

Audio books

- Hartmut Sommer: Bernhard von Clairvaux - the places where a great mystic lived. Auditorium Maximum, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-534-60073-1 .

Secondary literature

- Marie Gildas: Entry in the Catholic Encyclopedia , Robert Appleton Company, New York 1913.

- Tiburtius Hümpfner SOCist : Iconography of St. Bernhard of Clairvaux . Dr. Benno Filser Verlag, Augsburg, Cologne, Vienna 1927.

- Pius Maurer: Bernhard von Clairvaux in the Biographia Cisterciensis

- Pope Pius XII : Encyclical Doctor Mellifluus in English translation

- Werner Robl: Bernhard and Abelard

- Entry in the dictionary of saints

Individual evidence

- ↑ Paul Sinz (ed.), The life of St. Bernard of Clairvaux (Vita prima), Düsseldorf 1962, [Chapter 7] p. 65.

- ↑ Georges Duby, Der Heilige Bernhard und die Kunst der Zisterzienser , Stuttgart 1981, p. 9. ISBN 3-12-931800-3 .

- ↑ Étienne Delaruelle: L'idée de la Croisade chez Saint Bernard , in: Mélanges Saint Bernard (Dijon 1953), pp. 53-67.

- ↑ Ernst-Dieter Hehl, Church and War in the 12th Century. Studies on canon law and political reality, Stuttgart 1980, p. 134.

- ↑ Gerhard Winkler (ed.), Bernhard von Clairvaux, Complete Works lat.-dt. , Vol. 3, Innsbruck 1992, pp. 890-893.

- ↑ Arnold Angenendt, Tolerance and Violence. Christianity between the Bible and the sword, Münster 2007, pp. 403–404.

- ↑ Archivio della Latinita italiana del medioevo: Liber ad milites Templi de laude novae militiae ( Memento of 5 November 2013 Internet Archive ), in Latin, accessed January 17, 2007. German translation: Book of the Knights Templar - eulogy to the new one Chivalry , accessed January 17, 2007.

- ^ Arno Paffrath, Bernhard von Clairvaux. Life and Work, Altenberg-Bergisch Gladbach 1984, p. 126.

- ↑ Erwin Iserloh : Die Deutsche Mystik , in: Hubert Jedin (ed.), Handbuch der Kirchengeschichte III / 2, Freiburg 1973, pp. 460–478, here p. 463

- ↑ St. Bernhard in Dante's Divina Dommedia , in: Cistercienser-Chronik 19 (1907), pp. 321-324.

- ↑ Sabine Poeschel: Handbuch der Ikonographie (Darmstadt 2005), pp. 223–224.

- ^ Franz Posset: Amplexus Bernardi: The dissemination of a cistercian motif in the later middle ages , in Cîteaux 54 (2003) 3–4, pp. 251–400 (with a chronological list of the early amplexus representations).

- ↑ Archive link ( memento from March 15, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) on June 16, 2012

- ^ Dominique Nogues , Mariologie de Saint Bernard , 2nd edition, Paris 1947.

- ↑ JM Delgado Varela, Principios mariologicos de San Bernardo , in: Estudios Marianos 14 (1954); Pp. 157-186.

- ^ Leopold Grill, The alleged opposition of St. Bernhard von Clairvaux on the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of Mary , in: Analecta Cisterciensia 16 (1950), pp. 60-91.

- ↑ See also Karl-Werner Gümpel: On the interpretation of the Tonus definition of the Tonale Sancti Bernardi (= treatises of the humanities and social sciences class of the Academy of Sciences and Literature in Mainz. Born 1959, No. 2).

- ^ Matthias Untermann, Forma Ordinis. The medieval architecture of the Cistercians, Kunstwissenschaftliche Studien 89, Munich 2008.

- ^ Robert Haller, Early Dominican Mass Chants. A Witness to Thirteenth Century Chang Style (Phil. Diss. Washington 1986), pp. 74-79. (PDF; 7.2 MB)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bernhard of Clairvaux |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Bernard de Clairvaux (French) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | medieval abbot, crusade preacher and mystic |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1090 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Fontaine-lès-Dijon Castle near Dijon |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 20, 1153 |

| Place of death | Clairvaux near Troyes |