genealogy

Genealogy (from ancient Greek genealogia "genealogy, family tree "; dating back to genea "birth, descent, clan, family " and lógos " teaching ") in the narrower sense, the auxiliary historical science of family history research , general language genealogy or genealogical research (subject of this article). Genealogists or genealogists deal with human relationships and their representation. The genealogy of a person or family is generally understood to be the listing of their ancestors known by name .

In a broader sense genealogy denotes the genetic connection of a group of living beings, the biological descent of a living being from other living beings; In animal breeding , it is the prerequisite for a breeding value assessment . Derived from this meaning genealogies are also spoken of in the context of the history of ideas, so the Mathematics Genealogy Project records the published doctoral theses in mathematics .

In a figurative sense is in the Humanities under Genealogy a historical method meant that investigates the historical development of various issues of the present. In 1887, for example, the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche reconstructed in his Genealogy of Morals that moral concepts are not derived from absolute values, but are something that has become in the course of history. For the French philosopher Michel Foucault (1926–1984) genealogy was a central term for his developmental analyzes of mental illnesses and the prison system .

Subject of genealogy

Starting from a certain person as ego “I” or test person “test person”, genealogy investigates the ancestry of their ancestors (ancestors, hence “genealogy”) in ascending line , and their descendants in descending line . People who are genealogically related are related . As soon as the description of the connections goes beyond the pure representation of the descent, one speaks of "family history research" - for example with the aim of finding out the living conditions of distant ancestors.

While genealogy is often pursued for personal or family interests and as a recreational activity, genealogy is important in identifying heirs . While some countries restrict inheritance claims to grandparents and their descendants, inheritance claims are possible under German inheritance law if the common ancestor lived in the Middle Ages or even earlier.

Special questions

- Emigration research

- Research into specific professional groups ( scholars , pastors , glassmakers , millers , executioners )

- Complete registration of the population of a place in a place family book

- Wirte- and courtyards Research (owner of guest and farms )

- Determination of the loss of ancestors through the relationship of ancestors

Since genealogy is a sub-area of historical research, other related or obvious areas such as naming and heraldry , home and military history , war graves , but also degrees of kinship are often dealt with.

An independent area of genealogy is name research on the origin, distribution and meaning of family names .

Research methods

The interest in genealogy usually comes from one's own family. You start with questions to parents, grandparents and relatives about family relationships and the origin of the ancestors. Family books , family photos and a possibly still existing ancestral passport provide further information. In some regions, the tradition of death cards or death notes has existed for decades , which are ideal for genealogical research, as they often contain a photo of the deceased as well as dates of birth and death and other information (names of relatives, name at birth, references to the Type of death) included. In addition, especially in the last generations, you will also find something in the cemetery. Often there are other data on the tombstones as well. Photos, documentary evidence and the biographies and life pictures of grandparents, great-grandparents and other relatives are the basis for a family chronicle .

Further research requires dealing with the sources; this requires specialist knowledge that every genealogist acquires in the course of his research. In this context, the pitfalls of personal-historical research on the Middle Ages were pointed out and "the sometimes somewhat bold hypotheses about family relationships [...] were clearly criticized."

Research on older sources such as church registers or court books requires the ability to read ancient scriptures (see palaeography ) and, in Catholic areas, mostly knowledge of Latin. Variability of surnames and an extensive marriage circle of the people to be researched must be taken into account. Research sometimes comes to the so-called dead point that has to be overcome. With the doubling of the number of ancestors in each generation, the picture of personal ancestry expands to include topics such as home history , social history , economic history and population history of entire places (see local family book ) or regions.

Instead of your own, you can also research the ancestors and descendants of historical personalities or outstanding representatives of certain professional groups. At a more mature stage, the researcher comes to ever greater accuracy and detail in collecting the data. For example, one can include the siblings of the ancestors, their spouses, their children and the social position of their respective in -laws , which makes scientific secondary analyzes of the data meaningful and particularly meaningful.

An important quality goal of data collection and presentation in genealogy, which is largely carried out by lay researchers, is to provide the researchers with scientific standards and to motivate them to the extent that the data collected meet the criteria of quality and scientificity and are incorporated into the scientific discourse ( Publication, presentation, possibly internet) and can be placed in a historical context.

Computer genealogy

With the boom of the Internet, genealogy has also experienced a strong boom. Worldwide contacts between researchers can be established quickly and inexpensively through the medium of the Internet. In genealogical databases on the Internet today there are many millions of researched pedigrees and family trees to be found. With GEDCOM , a standard for the mapping and structuring of genealogical data has also been established, which is supported by a large number of genealogical programs .

With some genealogists the attitude is observed that this way of working is genealogy itself. In doing so, it is sometimes neglected that the material for such databases can only be created through thorough work on the sources.

Some American and also German companies use the topic of genealogy to determine personal data inexpensively. Users of web portals enter addresses and dates of birth about their relatives - but these can be misused in the course of viral marketing or by affiliate networks . In this way, unusually large amounts of personal data about living and deceased people can be marketed. The data protection law does not work here often, as when the user has agreed to the terms and conditions of cross-border processing and thus the German law is not applicable.

In 2019, Ancestry.com in Germany received the negative “ BigBrotherAward ” in the newly created biotechnology category , “because it encourages people interested in family research to send in their saliva samples. Ancestry sells the genetic data to commercial pharmaceutical research, enables covert paternity tests and creates the data basis for police genetic screening ”(see Computer Genealogy: Abuse ).

Scientific working method and meaning

Since scientific research requires representativeness for many questions , genealogical sources have long been considered unsuitable. For example, in the work of Jacques Dupaquier on the social history of France , representative samples were collected, with Dupaquier based on master lists .

For genealogists, too, the scientific nature of the working methods means the objectivity of research, regardless of the person who conducts it. Ancestry is only considered proven if other researchers, based on the available sources , must arrive at the same results. If there are doubts and uncertainties, these must be marked as such in the ancestral lists . Calculated values or mere assumptions must be recognizable as such.

Even established academic disciplines usually do not have permanent control bodies, but rather require that all researchers strive for truthfulness . The criterion that separates the researcher from the fantasist (for example with an unknown father for an illegitimate child) or even cheaters is the repeatability of the parentage verification by other researchers. Careful work, for example by including new, previously unknown sources and methods (see also paternity reports ) can in individual cases lead to revisions of ancestry that was previously considered to be sufficiently proven.

There is a mutual relationship between conceptual history and genealogy that has so far received little attention. Because language and concepts are changeable in space and time, over which genealogical research extends. Surnames , place names , place names , job titles , kinship terms , legal terms and folkloristic important terms - including the formulas with which the priest premarital sexual intercourse and illegitimate birth denounced - are included in good ancestry lists thousands. For example, if one maps the names of the occupations from hundreds of such lists, separated decade by decade, then the regional distribution, e.g. for the names of farmers and the change in terms, can be proven, which in turn is the prerequisite for correct classification of social history .

The genealogist can help to increase the informative value of his work by reproducing information on different spellings of family names and occupations in his work true to the source and not modernizing or overly generalizing them. This includes some experience of local history and a sure instinct: To differentiate between “baker” and “becker” is almost meaningless, but “butcher” from “butcher” is significant in terms of linguistic and conceptual history and the line between “Wagner” and “Stellmacher” even separates dialects - Spaces.

Family relationships can be illustrated with the help of genograms .

Genealogy and Inheritance

The beginning of the 20th century was shaped by the naive idea that genealogical data could make a direct contribution to clarifying the inheritance of numerous characteristics (" genetic genealogy "). One simply took given linguistic wholes for psychological variables, such as “ambition” and “good faith”, just as one took “blond hair” and “blue eyes”, and examined the inheritance of “ambition” and “good faith”.

Serious results could not be achieved with these methods, since the effects of upbringing and other environmental influences on the development of psychological properties are ignored. Only a few, mostly monogenic characteristics (such as hemophilia ) follow a genealogically traceable inheritance. In many more complex ( polygenic ) situations it has proven difficult or so far impossible to identify individual gene effects.

Genealogy and home history

Most of the time, the genealogist is not only familiar with the local history of certain areas, but also captures a living image of history in his work and explores the historical legacy. In almost every list of ancestors , the ancestors accumulate in certain communities in the 16th to 18th centuries , and even make up a considerable percentage of the population in some villages . Basic knowledge of local history is therefore indispensable for the classification and evaluation of professions, the purchase prices of goods and houses or concepts related to the landscape. In many cases, the existing literature on local history ( chronicles ; supplements in daily newspapers; series of values from our German homeland ) is a valuable genealogical source, in other cases the genealogist works on the local family book , the local chronicle , or works out contributions on local history and life pictures . Local history connected with genealogy and with personal reference to the present is not an abstract story . By connecting people, events, dates, houses and the living conditions of the past with their social conflicts and struggles, often including legends of origin , a comprehensive picture is created.

Sources for genealogists

Central Europe is one of those parts of the world in which suitable sources for family history research have been available since the 16th century in the form of church registers and court trade books, and since the end of the 18th century also in the form of civil status books , in which the main life dates for every person have been available can be proven, provided that the relevant sources have not been destroyed.

Other important source groups of genealogy are, for example, citizen registers , funeral sermons and personal documents , university registers , parish registers , wills and other files from which the relationship of the people to each other or at least - so that the dead point of the research can be overcome - their hometown is recognizable, such as for example the passenger lists of the emigrant ships from the 19th and 20th centuries and the draft lists . Another group of sources are lists and files that prove the existence of people in a specific place and at a specific time and their social position, such as tax lists and address books . Often these and other sources are only available for certain population groups, such as the social upper class .

Aids were then developed on the basis of the sources already mentioned and other sources: cards, files and books. This includes the local family books , house books , property chronicles and servant books , but also the ancestral index of the German people .

With the help of Internet technology, many of these sources are gradually being published in online genealogy databases .

Church registers are located in the parish archives of the respective parish and religious community . In some territories, the originals of the church registers or their copies and film adaptations are concentrated in central archives and accessible there for use. These central archives can be church or state archives, in the responsible diocese , such as in Münster , in the responsible regional church archive, such as in Kassel , or in the archives based on an agreement with the church in the regional archive, such as in Innsbruck for Tyrol the Swiss cantons and Alsace . The respective responsibility and the storage location must be determined in each case.

Court trade books and other important sources can be found in the relevant state archives , and other source groups in the city archives . Since 1875 in Germany are civil status in the registry offices out.

By far the largest genealogical archive is maintained by the Utah Genealogical Society, founded in 1894 . Research into family history has more than just important religious significance within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (→ Mormons ) (see Baptism in the Dead ). Therefore the Genealogical Society of Utah archives church records and other genealogically important documents on the one hand on microfilm and on the other hand now also on digital media. The church book films are publicly available at many family genealogy centers around the world ; Personal data (of people who have already died) and family relationships can also be viewed on the Internet.

Numerous church book adaptations, especially from the former eastern German regions, can also be found in the Central Office for German Personal and Family History in Leipzig .

The Protestant regional church archives , among others, are now making church records available centrally via the Archion Internet platform .

Presentation of the results

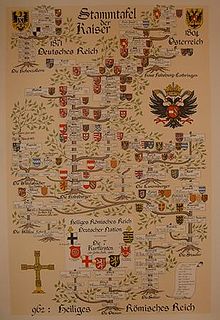

The research results are in genealogical tables illustrated, both with ascending ( ancestry , ancestors) and descending ( descent , descendants) content occur. Both directions can be in the form of a table or a list. The ascending line is referred to as a pedigree or ancestor list , the descending line as a descendant or descendant list . A combination of the two tables, in which all ancestors and descendants of a selected person are shown, are generally also called "hourglass" tables due to their shape.

If only the descendants of a person are recorded who have the same family name or who once had the same family name or were married to these persons (although strict adherence to this rule is not always possible, for example due to name changes, adoption, foreign naming rights and others) is it a family tree or family list. In reference works , the family name is a sorting criterion and thus the family tree or family list is the natural form of representation, also in "family stories". In monographs dealing with a particular person and their descendants, tables and lists of descendants predominate.

Whether the table or list form is selected for the presentation of genealogical results depends, among other things, on how extensive the data material is and how clearly it is to be presented. Basically, the more generations to be shown, the more likely it is that the list form is appropriate.

In addition to the representation of the ancestors or descendants, the following are known:

- Consanguinity tables and consanguinity lists (also known as kinship or clan tables ), in which all blood relatives are presented starting from a test person , both in ascending and descending order, with consequent increased problems with the representation, as well

- Affinity tables and affinity lists which, in addition to consanguinity, also include persons in law and their families in the display.

The family relationships of the inhabitants of a place are shown in a place family book ; limited to the homeowner only, in a house book .

Permanent backup of genealogical results

Safeguarding requires the permanent storage of research results that is accessible to the public. Of all the materials compiled by genealogists in the 20th century (lists of ancestors, church book mapping ), half have now been destroyed and lost. With the current state of computer-aided printing and copy technology that is accessible to everyone, this should no longer be a problem today.

If no publication of the work in a magazine or book series is sensible or possible, at least half a dozen printouts and copies of the original should be made of each genealogical work. The German Library (which also has funds available for partial reimbursement of costs for such submissions) should and must receive two of them , one copy belongs in the responsible state library of the respective federal state, one in the Central Office for German Personal and Family History in Leipzig, and further copies in the regionally responsible state archive, the responsible rectory (in the case of a local family book) and at least one important regional scientific library and a city archive. This distribution key for the locations should be indicated on the title page at the top right. If such works that are not available in bookshops are cited, the location should always be stated.

In the estate , suitable (i.e. ordered and with a list of sources) materials should be handed over to archives, museums or libraries based on clear, written specifications made during their lifetime. According to all experiences, materials remaining in private ownership (with the biological heirs) for public use and thus for further research are often completely lost. Even card files, even if they get into archives, are unique as they are not protected against disorder and theft of individual cards. Their use is tied to a single location and is therefore difficult. Here, too, a coherent manuscript with several printouts is the safest solution. This is the only way to make the immense work usable for further research. File files that end up in any archive as a disordered legacy often remain undetectable and practically lost for decades.

Securing does not only mean safekeeping, but above all guaranteeing further public use, which for the genealogist was also the prerequisite for his own work.

The Utah genealogical society of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (→ Mormons ) provides assistance in securing important documents and family trees. These data can be digitally archived free of charge via the relevant local research centers or the Internet. These data can be viewed worldwide after a certain period of processing. Here, too, the rule is that only data from deceased persons can be viewed.

A special genealogical database, the so-called WW-Person , was created to ensure the genealogical results of European aristocratic families .

history

Germany until 1945

The German geographer and polymath Johann Gottfried Gregorii regarded genealogy as an auxiliary science of history and geography, in keeping with the zeitgeist of the beginning of the 18th century, and between 1715 and 1733 published his five-volume genealogical description of the European nobility under the title: The now living EUROPE. The Cosmographic Society associated with the Homann heirs wrote about this in 1750: "A world describer must have genealogy and coat of arms art", and: "Genealogy contains the reason for most of the changes in the rulers and the resulting territorial divisions."

“There was more genealogy among people than history,” said the historian Johann Christoph Gatterer (1727–1799), who in 1788 published an outline of the genealogy . In the ancient civilizations the genealogy of heroes and kings was the form of historical chronology par excellence (think of the first chapters of the Bible ). The early medieval genealogy was primarily a history of the lineage of the high nobility. The nobility as a whole needed proof of ancestry in order to assert claims of ownership or to prove qualification for certain offices.

Only at the turn of the modern age did wealthy middle-class families begin to write down their ancestors. The guilds required a birth certificate from every foreigner who wanted to learn or practice a trade in the city . With the associations Der Herold (Berlin 1869) and Der Adler (Vienna 1870) the first genealogical associations for heraldry and genealogy emerged. In 1902, Der Roland was founded in Dresden as the first civil society in the world.

In parallel, the parentage assessment in animal breeding developed . Since the 18th century, stud books have also been kept for racehorses, for example, followed later by herd books for numerous farm animal breeds .

At the turn of the 20th century genealogy began to really develop in breadth and depth. The Gotha Genealogical Pocket Books ( Almanach de Gotha , in short: Der Gotha ), which had originally appeared as the Genealogical Court Calendar in Gotha since 1763 and were published by the Justus Perthes publishing house in Gotha from 1785 to 1944 , now opened up to and gave to middle-class families Origin, partly from rural and other roots. In 1904, the Central Office for German Personal and Family History was founded in Leipzig . In 1913 the handbook of practical genealogy appeared. During this pioneering time, the young genealogy was shaped by forward-looking and interdisciplinary thinking personalities who wanted to put genealogy in the service of the social sciences . In genealogy, which is largely based on amateur research , there was little response to these suggestions.

In the 1920s, the anthropologist Walter Scheidt and his colleagues began to evaluate church records in terms of population genetics, for which he sought the collaboration of genealogists. Encouraged by several pastors, a line of work began to emerge under the heading of “ folk genealogy ” that no longer only focused on the genealogy of the wealthy, but also of the entire population.

Karl Förster (1873–1931) recognized the need to better organize genealogical lay research and to collect data centrally for research purposes. As early as 1921 he founded the circulation of ancestors lists, the data of which was incorporated into the ancestral index of the German people . Before 1933 there were already a large number of regional genealogical associations and journals in the German-speaking area . In her lectures and publications, catchwords such as heredity , race and homeland were common.

From 1933 onwards, National Socialist politics tried determinedly to bring the genealogical associations into line, and genealogy was placed at the service of the blood-and-soil ideology and anti-Semitism . The law on civil servants required proof of so-called Aryan descent (for example through the ancestral passport ), and genealogy became genealogical research . The churches were given the task of determining which Jews had converted to Christianity and had been baptized in the 19th and 20th centuries . With the help of appropriate information, the descendants of the baptized people could be “unmasked as Jews”. In the Protestant Church of Schleswig-Holstein alone, around 150 employees worked in 17 church offices who researched, issued certificates of parentage and created registers on a daily basis. In the area of the then North Elbian Church , 7731 Christians of Jewish origin were identified, singled out and killed with the help of the church's own genealogy. In 1939 work on village clan books was carried out in 3,000 municipalities in Germany .

In 1934 the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Genealogy and Demography was founded in Munich , in which a series of papers on the inheritance of mental illnesses, but also the genealogy of gifted people , were completed. This had the consequence that in 1945 almost the entire organizational basis of genealogy was dissolved.

International aspects

Until 1945 the development of the factual references of genealogy to population history , economic history and social history in the German-speaking area had a temporal advantage. Around 1950 the genealogists in Germany and Austria had started to reactivate old associations, publishers and magazines from the time before 1933 or to found new ones. In 1969 the first working group on genealogy was founded in the GDR in Magdeburg within the association of the Kulturbund. Although “International Genealogy Congresses” have been taking place since 1929, the emphatically regional and national language character of the sources has so far prevented the development of an international and theoretically comprehensive genealogy. However, the development of genealogical computer programs undoubtedly causes an increasing internationality. After 1945 new impulses came from France , the Netherlands , Sweden , Great Britain and the USA , where family history research has developed into a widespread leisure activity in recent decades .

United States

In the USA, John Farmer (1789–1838) in particular was a leader. Previously, the American colonists used pedigrees to prove their social positioning within the British Empire. Farmer had a more egalitarian, republican ethos. The American genealogy was increasingly used to highlight references to the Founding Fathers of the United States and heroes of the American War of Independence . An important female caregiver was the Indian Pocahontas , whose numerous descendants were mostly members of the white upper class, to which many representatives of the " first families of Virginia" (FFV) trace their ancestry back to this day . Her baptismal name Rebekah alluded to the role assigned to her as the archmother of North American New England . Around 1900 these references were considered with a number of exhibitions, such as the Jamestown Exposition of 1907, as well as researched in historical societies such as the Preservation Virginia . Farmer's efforts led to the founding of the New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS), which is committed to the preservation of historical records and family books in New England and publishes the New England Historical and Genealogical Register .

For religious reasons, the Utah Genealogical Society has taken on an organizational leadership and leadership role in the use of computers in genealogy internationally. It was founded in 1894 with the aim of helping members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints ( Mormons ) gather family history information. Vicarious baptism and other ceremonies for deceased non-Mormon ancestors are part of Mormon religious practice. As a non-profit organization, the Genealogical Society makes its facilities and materials generally available to family researchers and is systematically expanding its database worldwide.

Genealogy in Judaism

Genealogy has a special role in Judaism. In the Torah , genealogy is translated as toledot ("generations"). In Hebrew, terms like yiḥus and yuḥasin refer to legitimacy or nobility , in modern Hebrew שורשים shorashim ("roots") orגנאלוגי genealogi. To this day, the descendants of Levites and Kohanim as well as various rabbi families have received special recognition.

Judaism is a religious community that also claims to have a common ethnic background. The interest in genealogy stems from the written tradition of the biblical lineages , as can be seen against the background of a long history of persecution and displacement. In the 20th century, the Holocaust increased the role of Jewish genealogy as survivors sought to find missing family members or to preserve the memory of the lost. To this end, various genealogical institutions were founded, including the International Tracing Service (ITS) in Bad Arolsen , the Search Bureau for Missing Relatives in Jerusalem and, most recently, the creation of the central database of the names of Holocaust victims in the Yad Vashem memorial .

Genealogical associations and societies

Supraregional organizations

In the German-speaking area there are around 100 genealogical associations , mostly specialized in geographical regions, the majority of which are part of the umbrella association Deutsche Arbeitsgemeinschaft genealogischer Associations, founded in 1949 . V. (DAGV), which is the successor to the working group of German family and coat of arms associations, which was founded in 1924.

The Verein für Computergenealogie (CompGen) with over 3,700 members is responsible for national interests of general importance and the topic of computer genealogy in particular . This association focuses on the publication of genealogical research results on the Internet . In addition to many databases , the GenWiki is a wiki that deals exclusively with genealogy.

Regional associations

The genealogists often join associations in the regions where their ancestors came from. If you live in another area yourself today, you are often a member of the genealogical association or homeland association of your place of residence and of the association that is responsible for the home of your ancestors.

The largest and most active regional genealogical associations for the German-speaking area include:

- West German Society for Family Studies V. (WGfF), over 2050 members

- Association for Family Studies in Baden-Württemberg e. V. (until 2015 Association for Family and Heraldry in Württemberg and Baden e.V. (VFWKWB)), around 1200 members

- Genealogical Society in Franconia e. V. (GFF), about 1300 members

- Hessian family history Association e. V. (HfV), about 1000 members

- Bavarian State Association for Family Studies V. (BLF), around 1200 members

- Herold, Association for Heraldry, Genealogy and Related Sciences in Berlin , about 800 members

- Die Maus, Gesellschaft für Familienforschung e. V., Bremen, over 900 members

- Working Group for Central German Family Research e. V. (AMF), about 900 members

- Palatinate-Rhenish Family Studies (PRFK), over 850 members

- Oldenburg Society for Family Studies e. V. (OGF), over 800 members worldwide

- Familia Austria, Austrian Society for Genealogy and History , founded in 2008, more than 880 members (June 2020)

- Heraldic-Genealogical Society "Adler" , Vienna, about 700 members

- Genealogical Society Hamburg e. V. (GGHH), over 600 members

- Lower Saxony State Association for Family Studies e. V. (NLF), about 600 members

- Working group for Saarland family studies e. V. (ASF), over 500 members

- Genealogical-Heraldic Society of the Basel Region (GHGRB), over 500 members

- Pomeranian Greif e. V. - Association for Pomeranian Family and Local History, over 400 members

- Genealogisch-Heraldische Gesellschaft Bern (GHGB), over 300 members

- Genealogical-Heraldic Society Zurich (GHGZ), about 300 members

- Schleswig-Holstein Family Research e. V., about 300 members

- Society for Family Research in the Upper Palatinate V. (GFO), about 230 members

- Interest group Ahnenforschung Ländle (IGAL), about 200 members

- Working group on family history research in Jeverland (family history regulars' table), including mailing list approx. 200 participants

- Association for Mecklenburg Family and Personal History e. V. (MFP), about 180 members

- Brandenburg Genealogical Society "Roter Adler" e. V. (BGG), around 150 members

- Working Group Genealogy Thuringia e. V. (AGT), about 100 members

The former German settlement areas in east and south-east Europe were created by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Ostdeutscher Familienforscher e. V. (AGoFF, around 1000 members) as a research area. Individual sub-areas are worked on by their own associations, some of which have emerged from the AGoFF or work with it:

- Association for Family Research in East and West Prussia e. V. (VFFOW), over 1000 members

- Working group for Transylvanian regional studies (AKSL), over 800 members

- Working Group of Danube Swabian Family Researchers (AKdFF), over 700 members

- Artushof Association Thorn e. V., about 600 members

- Association of Sudeten German Family Researchers (VSFF), over 500 members

- German-Baltic Genealogical Society V. (DBGG), about 100 members

Associations with special research topics

Some associations are dedicated to the descendants of refugees who came to Germany because of religious persecution:

- German Huguenot Society e. V. (DHG)

- Salzburg Association V., about 1000 members

Clubs abroad

There are also some associations abroad whose members research their ancestors in German-speaking countries:

- Anglo-German Family History Society, Great Britain

- Centraal Bureau voor Genealogie, Netherlands

- Nederlandse Genealogische Vereniging, Netherlands

- Swiss Association for Jewish Genealogy, Switzerland

- Society for German Genealogy in Eastern Europe, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

- Werkgroep Genealogisch Onderzoek Duitsland, Netherlands

Family associations

In addition, there are also family associations and clubs in which the descendants of a specific person, those who have a family name or people who are related to one another are organized:

- Adam Ries Association V. (ARB), descendants of the arithmetic master Adam Ries , over 200 members

- George Koppehele'sche Family Foundation , descendants of the siblings of Magdeburg canon Georgius Koppehele

- Küchmeister and Lietzo family scholarships in Zerbst , descendants of the Zerbst families Küchmeister, Lietzo and Ziegenhagen

- Lutheriden Association e. V., descendants and relatives of Martin Luther , around 200 members

- Hofrat Simon Heinrich Sack'sche Family Foundation , descendants of Hofrat Simon Heinrich Sack (1723–1791) from Głogów ( Lower Silesia ), around 17,000 members

- Goldberg'scher Familienverband e. V., descendant of Warnsdorf Chief Justice Michael Goldberg († 1641), based in Rheine (Westphalia)

See also

- German Genealogy Day

- Degener & Co (specialist publisher, genealogy magazine ) - Starke Verlag ( genealogical manual of the nobility )

- Genealogical Signs and Symbols - Ancestral List Collection

- Generational designations

- List of Latin-German family names - List of the family names of Turkish

- Huguenot genealogy

literature

- Institut für Demoskopie Allensbach: Ancestry and family research: Every second person would like to know more about their ancestors. In: allensbacher reports. 2007, No. 7 (Genealogical Society in the Scientific Search Engine: Allensbach Survey on Genealogy in Germany; PDF: 14 kB, 5 pages ( Memento from December 9, 2008 in the Internet Archive )).

- Hermann Athens: Theoretical Genealogy. In: Sven Tito Achen (Ed.): Genealogica & Heraldica: Report of the 14th International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences in Copenhagen 25. – 29. Aug. 1980. Copenhagen 1982, pp. 421–432 (German; PDF: 1.3 MB, 13 pages on genetalogie.de).

- The people: genealogy. In: Ahasver von Brandt : Tool of the Historian. An introduction to the historical auxiliary sciences. 17th edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-17-019413-7 , chapter 2.3., Pp. 39–47 (11th supplemented edition 1986, first edition 1958; limited page previews in the Google book search).

- German Gender Book - CD-ROM. Genealogical handbook of middle class families. Complete list of volumes 1–216. Verlag CA Starke, Limburg an der Lahn 2003, ISBN 3-7980-0380-7 .

- Eckart Henning , Wolfgang Ribbe (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Genealogie. Degener, Neustadt an der Aisch 1972.

- Eduard Heydenreich: Handbook of practical genealogy. 2 volumes. 2nd Edition. Degener, Leipzig 1913 ( online: Volume 1 in DjVu format).

- Helmut Ivo: Family research made easy: instructions, methods, tips. Piper, Munich / Zurich 2006, ISBN 3-492-24606-0 .

- Bettina Joergens (Ed.): Jewish genealogy in the archive, in research and digitally. Source studies and memory (= publications of the North Rhine-Westphalia State Archives. Volume 41). Klartext, Essen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8375-0678-5 .

- Astrid Küntzel, Yvonne Leiverkus: Genealogy for eternity? Family research, history and archives together in the digital age. In: Archivist. Volume 61, 2008, ISSN 0003-9500 , pp. 48-49.

- Wolfgang Ribbe, Eckart Henning: Pocket book for family history research. 13th edition. Degener, Neustadt an der Aisch 2006, ISBN 3-7686-1065-9 (standard work).

- Reinhard Riepl: Dictionary for family and homeland research in Bavaria and Austria. 3. Edition. Waldkraiburg 2009.

- Viktoria Urmersbach, Alexander Schug : Warning, ancestors, I'm coming. Practice book modern family research. Past Publishing, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-86408-001-2 .

- Verein für Computergenealogie (Ed.): Ahnenforschung. In the footsteps of the ancestors. A guide for beginners and advanced users. Genealogy-Service.de, Reichelsheim 2004, ISBN 3-9808739-4-3 .

- Volkmar Weiss: Prehistory and consequences of the Aryan ancestral passport: On the history of genealogy in the 20th century. Arnshaugk, Neustadt an der Orla 2013, ISBN 978-3-944064-11-6 .

- Thomas Wieke: Genealogy. How to explore your family history. Stiftung Warentest , Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86851-085-0 .

- Joachim Wolters: Family and family tree research made easy. The Handbook of Genealogy. Goldmann, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-442-13677-6 .

Web links

Tools:

- Association for computer genealogy e. V .:

- Database: online project memorials to the fallen. Thilo C. Agthe, 2003–2012 (name inscriptions on war memorials).

- Web catalog: chgh.net (genealogical-heraldic web catalog of Switzerland with a large collection of coats of arms).

- Matriculation books: matricula-online.eu.

- Heraldic-Genealogical Society Adler in Vienna: adler-wien.at (Genealogy in Austria).

- Online service: roglo.eu August 2007 (information on 2 million people from the European nobility and contemporary history).

- Geogen: stoepel.net (geographical distribution of family names in Germany and Austria).

- List: vdda.de (noble family associations).

Individual evidence

- ^ Wilhelm Gemoll : Greek-German school and hand dictionary. Freytag / Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, Munich / Vienna 1965.

- ^ Wilhelm Pape , Max Sengebusch (editor): Concise dictionary of the Greek language. 3rd edition, 6th impression. Vieweg & Sohn, Braunschweig 1914, p. 480 ( page scans on zeno.org).

- ^ Werner Hechberger : Nobility in the Frankish-German Middle Ages. Ostfildern 2005, pp. 306–328, here p. 316. For his part, Hechberger refers to Hans K. Schulze : Reichsaristokratie, Tribesadel and Franconian freedom. In: Historical magazine . Volume 227, 1978, p. 361/362, as well as on Gerd Althoff : Relatives, friends and faithful. Darmstadt 1990, pp. 39/40.

- ↑ Big Brother Awards 2019 : Official website. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ↑ a b Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints : FamilySearch.org. Retrieved March 8, 2020 .

- ^ Herbert Stoyan : WW-Person: A WWW-Person database of the higher nobility in Europe. Own website, accessed on March 8, 2020 (1994–2010, around 820,000 people).

- ↑ Carsten Berndt: MELISSANTES. A Thuringian geographer and universal scholar (1685–1770). Rockstuhl, Bad Langensalza 2013, ISBN 978-3-86777-166-5 , p. 127.

- ↑ Cosmographic Society: Cosmographic News and Collections for the year 1748. On the growth of world descriptive science, gathered by the members of the cosmographic society. Vienna / Nuremberg 1750, preface.

- ↑ Volkmar Weiss : In the shadow of the Nuremberg Laws. In: Prehistory and consequences of the Aryan ancestral pass. On the history of genealogy in the 20th century. Arnshaugk, Neustadt an der Orla 2013, ISBN 978-3-944064-11-6 , pp. 151–178.

- ↑ comparisons about the new index for genealogy with ancestors index and clan index as they were driven from Munich publisher Lehmann.

- ↑ Christine Kükenshöner: German blood in church registers. ( Memento from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) In: Evangelische Zeitung. June 18, 2008, accessed March 8, 2020.

- ^ A b François Weil: Family Trees. A History of Genealogy in America. Harvard University Press, Cambridge 2013, Chapter 1.

- ^ Robert S. Tilton: The Evolution of an American Narrative. Cambridge University Press, 1994, p. 182 (English).

- ^ François Weil: John Farmer and the Making of American Genealogy. In: New England Quarterly. Volume 80, Issue 3, 2007, pp. 408-434 (English).

- ^ A b Jacob Liver, Israel Moses Ta-Shma, Sara Schafler, Efraim Zadoff: Genealogy. In: Michael Berenbaum , Fred Skolnik (Ed.): Encyclopaedia Judaica. Volume 7. 2nd edition. Macmillan, Detroit 2007, pp. 428-438.

- ^ Sara Schafler: Jewish Genealogy. In: Encyclopaedia Judaica year book. Volume 5. 1983, pp. 68/69 (English).

- ^ Emil G. Hirsch: Genealogy. In: Isidore Singer (Ed.): Jewish Encyclopedia . Funk and Wagnalls, New York 1901-1906.

- ↑ Hessian Family History Association : Official website.

- ^ Bavarian State Association for Family Studies : Official website. Bavarian State Association for Family Studies V. (BLF), accessed on March 8, 2020 (family research in Altbayern [Oberbayern, Niederbayern, Oberpfalz] and Swabia).

-

^ Familia Austria: Official website. Austrian Society for Genealogy and History, accessed June 24, 2020 .

As of June 2020 = 880 members: [1]

- ^ Brandenburgische Genealogische Gesellschaft e. V .: Official website. Retrieved March 8, 2020 (Family and Regional History Research in Brandenburg).

- ↑ Hofrat Simon Heinrich Sack'sche Family Foundation : Official website.

- ^ Goldberg'scher Familienverband e. V .: Official website.