Alsace

|

Alsace Former French Region (until 2015) |

|

|

|

| Basic data | |

|---|---|

| Today part of | Grand Est |

| Administrative headquarters | Strasbourg |

|

population

- total January 1, 2018 |

1,898,533 inhabitants |

|

surface - total |

8,280 km² |

| Departments | 2 |

| Arrondissements | 9 |

| Cantons | 40 |

| Municipalities | 904 |

| Formerly ISO 3166-2 code | FR-A |

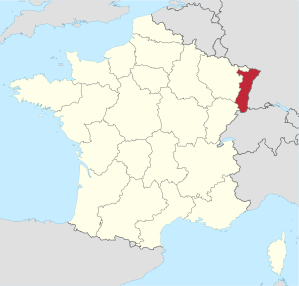

The Alsace (in older notation also Alsace , Alsatian 's Alsace's elses , French Alsace [ alzas ]) is a European authority in the region Grand Est in the east of France . It extends over the southwestern part of the Upper Rhine Plain and extends in the northwest with the Crooked Alsace to the Lorraine plateau. Alsace borders Germany in the north and east and Switzerland in the south . The capital of the local authority is Strasbourg.

In terms of landscape, Alsace is usually described as the area between the Vosges and the Rhine . The political borders that define Alsace, on the other hand, have changed several times in the course of its history. The Duchy of Alsace (7th and 8th centuries), the two Landgraviates of Alsace (12th-17th centuries) within the Holy Roman Empire and the first French province of Alsace (17th-18th centuries) are historically important .

The current boundaries of the Alsace is largely summarized from the 2021 departments of Bas-Rhin and Haut-Rhin is, based on the boundaries of the French Revolution (department boundaries, crookedness Alsace) and the Frankfurt Peace 1871 ( Belfort is separated from Alsace).

Since the 17th century, Alsace changed its political affiliation several times between the Holy Roman Empire or German Empire and France.

Between 1973 and 2015, the two Alsatian departments together formed a separate French administrative region of Alsace (Région Alsace) . With 8280 km² it was the smallest region in terms of area on the French mainland and had 1,898,533 inhabitants (as of January 1, 2018). As part of the regional mergers , the Grand Est (Great East) region with the capital Strasbourg was founded on January 1, 2016 . This includes Alsace, Lorraine and Champagne-Ardenne . As a European regional authority , the two départements of Alsace were again merged into one political unit " European regional authority Alsace " at the beginning of 2021 .

Names

The name Alsace refers to a landscape and political entity that was attested as early as the early Middle Ages . Early Latinized mentions are in pago alsacense (772) and in pago alisacense (774), the name appears purely in German as elisazon for the first time in a document from 877. It derives from early Old High German ali-sāzzo "inhabitant of the other (to be added :) Rheinufers ”or, elliptically abbreviated, from early High German ali-land-sāzzo “ residents in a foreign land ”and is thus a combination of old high German ali-, eli- “ other, foreign ”, possibly land “ land ”and sāzzo “ seated person , Resident ”. Among the "residents of the foreign country" one should most likely think of the Franconian new settlers who were settled by the Franconian monarchy on the left bank of the Rhine between Basel and the Palatinate after the Battle of Zülpich in 496 and met Romans and Alemanni there.

Due to the changeful history of Alsace between the Germanic (German) and Romanic (French) cultural areas, names based on it were created. Since Alsace was German-speaking and is still partially German, Welschi or Walschi in Alsace stands for inner French in general and for the Romance ( Lorraine / French) language enclaves on the east side of the Vosges (pays which) in particular and their language . The Alsatians are also known colloquially to derogatory in the German-speaking neighboring regions as Wackes , which in Alsatian dialect initially meant rural travelers or unemployed and partly corresponds to the reverse term Boche .

geography

Alsace borders Germany (in the north Rhineland-Palatinate , in the east Baden-Württemberg ) and Switzerland (cantons of Basel-Stadt , Basel-Landschaft , Solothurn and Jura ). In the west, Alsace borders on Lorraine and in the south on the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region .

Today's Alsace has a north-south extension of 190 kilometers, while the west-east extension is only 50 kilometers. In the east, Alsace is bordered by the Rhine , in the west for long stretches by the main ridge of the Vosges . In the north, the Bienwald and Palatinate Forest mark important border areas, in the south the northern edge of the Jura and in the south-west, in the open gate landscape of the Burgundian Gate , the border, which dates back to 1871, approaches the watershed between the Rhone and the Rhine.

The geological history extends from the Precambrian to the Quaternary .

The main natural units in Alsace are :

- The vast majority is taken up by the Alsatian Plain (Plaine d'Alsace) , which forms the southern part of the Upper Rhine Graben with Breisgau and Ortenau on the German side and the Petit and Grand Ried on the Alsatian side . The Ill flows through it and is characterized by the cultivation of grain . There are also large forest areas such as the Hagenauer Forest in the north and the Harthwald in the south. In addition to wide plains, there are also undulating to hilly areas (for example Kochersberg northwest of Strasbourg, western Sundgau and eastern Burgundian gate, area between Hagenauer Wald and Bienwald).

- In the west, the landscape is dominated by the Vosges , which are traversed by the broad valleys of the Ill tributaries. Here you will find high pastures (Hautes Chaumes) , which alternate with forests. The Große Belchen (Grand Ballon) is at 1,424 m the highest peak in Alsace and in the Vosges. In France, the areas north of the Zabern Valley are also counted among the Vosges (Vosges du Nord) , but they form a natural spatial unit with the Palatinate Forest .

- A narrow foothill zone mediates between the plain and the Vosges (analogous to the western edge of the Black Forest ). Wine- growing is typical of this “Piedmont of the Vosges” .

- In the far south, Alsace also has a share of the Jura ( Pfirter Jura).

coat of arms

Blazon : In red, a white diagonal right bar with a lily meander and three golden crowns placed on both sides after the bar .

history

Prehistory and early history up to 58/52 BC Chr.

Today's Alsace region was first settled by humans around at least 700,000 years ago, and by Homo sapiens around 50,000 years ago . The Neolithic Revolution lasted in the 6th millennium BC. Chr. Indentation. The first finds that indicate a political upper class were made around 2000 BC. Dated. For the approximately 550-year-old Celtic period , which took place in Alsace from about 600 to 58/52 BC. Lasted, one assumes the predominance of small territories.

Roman period 58/52 BC BC to AD 476

With the conquest of Gaul by Caesar between 58 and 52 BC. BC Alsace also came under Roman rule, with which it remained until the end of the Western Roman Empire around the middle of the 5th century. During these 500 years or so, the Rhine was the Roman imperial border at the beginning and again since the 3rd century. It developed a Gallo-Roman , population assimilated since the 1st century. Chr. Also the first Germanic groups as well as for about 350 permanently settled Alemanni . The latter only developed a kind of pre-state (and pre-Franconian) independence in today's Sundgau.

Initially, the conquered areas were under military administration. In the year 89 or 90 the province Germania superior (Upper Germany) was founded, which also includes today's Alsace. In the course of the Diocletian reform of the Empire , southern Alsace was assigned to the province of Maxima Sequanorum in 297 , and the northern to the province of Germania prima (Germania I). The provincial border drawn here largely corresponds to the later or current borders between Sundgau , Upper Rhine and Haut-Rhin on the one hand and Nordgau , Lower Rhine and Bas-Rhin on the other.

Interim period

After the withdrawal of the Roman troops around 476, Alsace probably came under Ostrogothic protectorate together with Alemannia . About two decades later, around 496, Alsace and Alemannia became part of the Franconian Empire . Here, Alsace was part of the Duchy of Alemannia , which existed until the 7th century . After that, an Alsatian duchy existed under the Etichons until the middle of the 8th century .

Franconian Empire 511–925

In the Frankish times, from around 500 onwards, there was a strong immigration of Germanic settlers who gradually outnumbered the Gallo-Roman population. The name "Alsace" goes back to this time, see above for more information. Strasbourg, a bishopric since 614 , was the most important city in the region alongside Basel and Speyer .

As a result of the Franconian division of the Empire, Alsace changed its national political assignment four times between 842 and 925: 842 to the Middle Franconian Empire , 870 to Eastern Franconia , 913 to Western Franconia and finally in 925 to Eastern Franconia again. This slowly became the confederation of states of the Holy Roman Empire , as part of which most of the developing Alsatian regions and small states were regarded until the 17th century. Strasbourg developed into the second largest city in Eastern France (after Cologne).

Holy Roman Empire 925–1648

Back in Eastern Franconia (925), Alsace initially played a special political role, but formed part of the Duchy of Swabia from 988 to 1254 at the latest . Between the end of the 8th and the middle of the 10th century, the two counties Nordgau and Sundgau were established as administrative districts . The Jura areas (south to the Aare ) that had previously belonged to Alsace were separated.

Mainly due to the end of the Staufer in 1254 and the related quasi-dissolution of their Duchy of Swabia, but also due to the slow general disintegration of the central power in the empire, many different political rulers emerged. These quickly became the actual bearers of the most important political powers of government. They operated under the roof of the empire, since the 17th century under that of the Kingdom of France, and were tied to the empire and France to very different degrees. Regional political institutions were the estates and the imperial districts , in the French era Intendance , Governor and Conseil sovereign .

The princely houses of Habsburg (only until 1648), Hanau-Lichtenberg , Württemberg and Rappoltstein , the city of Strasbourg and the cities of the Ten- City League , the secular lords of the dioceses of Strasbourg and Basel, the Murbach monastery and the Count the possessions of the Lower Alsatian knighthood. The imperial city of Mulhouse joined in 1515 as facing site of the older Swiss Confederation and thus remained one of the few structures without French sovereign rights (to 1798).

French Kingdom 1648–1789

Between 1633 and 1681, the Kingdom of France gradually took over sovereignty in most of the Alsatian regions , partly by treaties (de jure) and partly by annexation (de facto), but mostly not the rights below the level of national rule. Habsburg, on the other hand, ceded all of its Alsatian rights and possessions in the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. The annexations (most recently Strasbourg in 1681) were carried out by France mainly as part of its so-called reunification policy . Due to the peace treaties of Rijswijk in 1697 and Rastatt in 1714 , the Kingdom of France now also took over de jure political power in the annexed areas.

However, France did not move the newly won territories to its own customs territory - the French customs border continued to run over the Vosges. Many rulers were only under French sovereignty , some of them could continue to act more or less autonomously and self-administered.

The combination of uniform sovereignty and the retention of the traditional customs and economic area were important factors in the cultural and economic heyday that Alsace experienced between 1648 and 1789. French spread throughout Europe, and even more so in Alsace, as the administrative, commercial and diplomatic language of the urban and rural elites. Otherwise, the Alemannic (and Romance) dialects in Alsace and the German language were retained; at the University of Strasbourg, for example, teaching was still in German.

After the French Revolution 1789–1871

At the beginning of the French Revolution in 1789, as part of the standardization and centralization of France, the traditional rights of the Alsatian rulers were dissolved and the two departments of Haut-Rhin and Bas-Rhin were founded. Since Mülhausen joined the French Republic in 1798, all of what is now Alsace has been part of France. The second peace of Paris in 1815 established the French external borders that are still valid today ( Landau and other smaller areas in northern Alsace became part of Bavaria ).

Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine 1871–1918

As a result of between France and Prussia conducted with the participation of the southern states war 1870-1871 in were Frankfurt Peace of 1871 parts of Eastern France, the majority of the two Alsatian departments and about the northern half of the neighboring Lorraine to the (1871 founded during the war and Ceded the German Empire to Prussia . The demarcation was made not only from a linguistic perspective, but also from a military perspective. For example, in the Schirmeck area, an area with a French-speaking population east of the Vosges ridge was included in the German Empire, as was a broad French-speaking strip along the new border in Lorraine with the city of Metz . The French-speaking Belfort and its surroundings (today's Territoire de Belfort ) remained with France due to the wishes of the Prussian military (shortest possible border line between Vosges and Jura). Within the federally organized German Reich, the ceded areas, which were formed into the so-called " Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine ", did not initially form an area of equal rank to the other sub-states, but were administered by the authorities of the Reich and Prussia. It was not until 1911 that Alsace-Lorraine was put on an equal footing with the other German federal states.

The Peace of Frankfurt also included the so-called “option”: by October 1872, the inhabitants of the new country Alsace-Lorraine could decide whether they wanted to stay or rather become citizens of France, which meant having to leave Alsace-Lorraine. For about a tenth of the population of Alsace-Lorraine, about 161,000 people, options were given to the authorities, about 50,000 citizens ultimately took advantage of them. French-speaking communities and families in Alsace-Lorraine, like the Polish-speaking regions of Prussia, were exposed to attempts at Germanization and assimilation . French remained the school and official language there only partially .

France between the wars 1918–1940

After the First World War , the Treaty of Versailles stipulated that the area ceded in 1871 was annexed to France again. The Territoire de Belfort , which had been part of the now rebuilt Haut-Rhin department until 1871 , was not reunited with it. Political life was largely based on pre-war patterns. In addition to two liberal parties, the Alsace-Lorraine Center Party was newly founded as the Union Populaire Républicaine (UPR).

The French language was introduced as the compulsory official and school language. The Imperial German officials and those who moved there after 1871 and their descendants (a total of 300,000 people) had to leave Alsace. Anyone who exercised the German “option” was naturalized as a Prussian citizen (uniform German citizenship has only existed since 1934). In return, many elderly people who had moved to France in 1871 returned.

Of the 1,874,000 inhabitants of Alsace-Lorraine, 1,634,000 were registered as native German speakers, with the Moselle-Franconian dialect predominating in "German-Lorraine" and the Alemannic dialect in Alsace. The ideas and aspirations for regional autonomy within France that developed against this background were unsuccessful, and the Alsace-Lorraine National Council, founded in 1918, soon dissolved. The General Commissariat formed in 1919 also quickly lost its importance. After 1924, an autonomy movement emerged which first demanded confessional, then more cultural (including linguistic) autonomy and which culminated in the founding of the National Autonomous Party in 1927 . After the so-called “conspiracy process” in Colmar (the four convicts were pardoned after two months), the cross-party alliance “Homeland Law Popular Front” was created, whose representatives - especially Charles Hueber - were elected mayor in Colmar and Strasbourg in 1929. Due to the sympathy of the Autonomist State Party for the NSDAP , the alliance broke up in 1933 when the UPR left.

Reich connection in World War II 1940–1945

With the conclusion of the western campaign in 1940, the German Wehrmacht initially occupied Alsace, placed it under a Reich German "civil administration" and merged it with the Gau Baden to form the new Gau Baden-Alsace . Through the annexation ( de facto ), the Nazi state took over sovereignty; the official cession of the area through treaties (de jure) with France, however, was no longer due to the ongoing war. Robert Wagner , the Gauleiter of Baden and head of civil administration in Alsace, pursued a violent policy of Germanization regardless of their mother tongue, during which 45,000 people were expelled or deported from Alsace. Of the approximately 130,000 people from Alsace and Lorraine (including many volunteers) who were recruited as ethnic Germans into the Wehrmacht and the Waffen SS between 1942 and 1944 , about 42,500 were killed. Most of the soldiers named Malgré-nous in Alsace (meaning: against our will) had been deployed on the Eastern Front. Many Alsatians had previously been recruited by the French army , but there were also Alsatian volunteers from the Waffen SS . A few Alsatians belonged to the French Resistance ( Resistance to). In an initiative launched in November 1944 , the Allies advanced, with the participation of the newly formed French 1 re Armée in large parts of Alsace, and had taken it back for France. Some parts of northern Alsace only came under French control in March 1945 through Operation Undertone .

France since 1945

After the end of the war, the French administration began to assimilate the region to the French language and culture, as it had done in the interwar period ; speaking German or Alsatian was now frowned upon in public and not allowed in schools until the 1970s.

In 1949 the newly established Council of Europe was given its seat in Strasbourg; he founded the "European tradition" of Alsace. In 1972 France received 21 regions as local authorities (cf. regions of France ). Since then, the two departments on the Rhine ( Haut-Rhin and Bas-Rhin ) have formed the "Alsace Region" (Région Alsace) until 2015 . The regional capital, Strasbourg, was chosen to host the European Parliament in 1979, making Alsace, together with the Benelux , a core region of the European Union . First, the European Parliament met in the meeting room (hémicycle) of the Council of Europe; In 1999 it moved to its own building.

The protests against the nuclear power plants in Wyhl and Fessenheim at the end of the 1970s are considered to be the birth of the German and French ecological movements . During this time, an autonomy movement developed again with the demand for bilingualism to be preserved , which, however, as everything German was burdened with memories of National Socialism for a long time, was only able to achieve little success.

In the 1980s, the German federal government provided financial compensation for the Alsatians who were drafted into the Wehrmacht during the Second World War, on average a little more than DM 3,000 per entitled person.

Since 1945, the Alsatian language and culture has been marginalized officially and politically, so that a large part of the population switched to French as the standard language: the urban bourgeoisie was already French-speaking in the interwar period, the workers and the rural population followed later. Due to the structural change in agriculture, urbanization, and immigration from other parts of France as well as Italy, Portugal, Turkey and the Maghreb is also the composition of the population changed. While in 1946 91% of the population said they spoke Alsatian, it was 63% in 1997 and only 43% in 2012. The official and school language in Alsace today is exclusively French. Knowledge of the autochthonous Alemannic dialects (summarized in the term Alsatian ) or High German is therefore strongly declining and can still be found predominantly among older people. For more details see under culture .

Close economic ties to neighboring regions can be found above all within the Regio Basiliensis and in the greater Strasbourg- Kehl area , the number of cross-border commuters and cross-border shopping and day-to-day tourism have risen sharply here in recent years. That is why there are now increasing economic and transport links along the entire eastern border of Alsace, which - within the framework of Franco-German relations - have contributed to the intensification of cross-border cooperation on the Upper Rhine since the 1970s .

On January 1, 2016, the former Alsace region was merged with the Lorraine and Champagne-Ardenne regions to form the Grand Est region , which led to protests among the population. In response to this, the French National Assembly decided in 2019 to create the Collectivité Européenne, in which the two departments of Alsace will be combined from 2021 (see above).

Cities

The most populous cities in Alsace are:

| city | Inhabitants (year) | Department |

|---|---|---|

| Strasbourg (Strasbourg) | 284,677 (2018) | Bas-Rhin |

| Mulhouse (Mulhouse) | 108,942 (2018) | Haut-Rhin |

| Colmar | 68,703 (2018) | Haut-Rhin |

| Haguenau | 34,789 (2018) | Bas-Rhin |

| Schiltigheim | 33,069 (2018) | Bas-Rhin |

| Illkirch-Graffenstaden | 26,830 (2018) | Bas-Rhin |

| Saint-Louis (Haut-Rhin) | 21,646 (2018) | Haut-Rhin |

| Sélestat | 19,360 (2018) | Bas-Rhin |

| Lingolsheim | 18,930 (2018) | Bas-Rhin |

| Bischheim | 17,137 (2018) | Bas-Rhin |

politics

Political organization (1972-2015)

The Alsace Region was created in 1972 and in the course of administrative reform in 2016 with the regions Lorraine and Champagne-Ardenne merged , leading to protests with five-digit number of participants. The region was divided into two departments :

| Department | prefecture | ISO 3166-2 | Arrondissements 2015 (until 2014) |

Cantons 2015 (until 2015) |

Municipalities | Inhabitants (year) | Area (km²) |

Density (inh / km²) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bas-Rhin | Strasbourg | FR-67 | 5 (7) | 23 (44) | 527 |

|

4,755 | 238.4 | ||

| Haut-Rhin | Colmar | FR-68 | 4 (6) | 17 (31) | 377 |

|

3,525 | 217 |

Alsace has a large number of municipalities , as in France - unlike in Germany or Switzerland - there were never any significant municipal mergers. Many congregations have simply joined together to form a communal association , to which they have only delegated some rights. Depending on their size and status, they are called Métropole , Communauté urbaine (CU) , Communauté d'agglomération (CA) or Communauté de communes (CC) .

The Eurométropole de Strasbourg was founded in 1966 as Communauté urbaine and in 2015 raised to the legal form of a metropolis. As a Eurometropolis, it also has to make cross-border contacts. It currently comprises 33 municipalities with around 505,916 inhabitants.

There are two communities of agglomeration in Alsace. The Mulhouse Alsace Agglomération comprises 32 municipalities and 255,000 residents, the Colmar Agglomération 9 municipalities and 95,000 residents.

On April 7, 2013, a referendum took place on the creation of an Alsatian regional authority by merging the Conseil général du Haut-Rhin and Bas Rhin and the Conseil régional d'Alsace . The referendum was accepted by a majority of the voters, but the turnout was too low so that it did not become legally binding.

→ A list and comparison of French and standard German versions of Alsatian place names can be found in the list of German-French place names in Alsace .

Regional administration

The regional government and head of the regional administration was the Conseil Régional d'Alsace , the regional council, until 2015 . The seat of the regional council was Strasbourg . A list of the presidents of the regional council can be found here . Alsace is traditionally bourgeois-conservative and tends towards the political right ; between 2010 and 2015 it was the only region that was not led by a left-wing government: the ruling UMP party and its allies had 28 representatives in the regional council, socialists and the Greens 14 , the Front National , which had one of its strongholds here for a long time (see below), but has now only achieved average election results here, 4.

Partner regions

The former regional council concluded an "Agreement on International Cooperation" (Accord de coopération internationale) with the following regions:

- Gyeongsangbuk-do , South Korea

- Jiangsu , China

- Lower Silesia , Poland

- Upper Austria , Austria

- Moscow Oblast , Russia

- Quebec , Canada

- Planning region West , Romania

economy

With a gross domestic product (GDP) of 28,470 euros per inhabitant, Alsace ranked second among the regions (in the old form until 2015) in France. In comparison with the GDP of the EU , expressed in purchasing power standards, the region achieved an index of 107.2 (EU-25: 100) (2003).

Alsace is a region where many industries are based:

- Viticulture (especially in the area between Schlettstadt and Colmar on the Alsace Wine Route ). See also the article Alsace (wine-growing region) .

- Hop growing and brewing ; Half of French beer production comes from Alsace, especially from the Strasbourg area such as Schiltigheim and Obernai . Kronenbourg has been brewed in Strasbourg since 1664, the name of the beer is derived from the Kronenburg near Marlenheim .

- forestry

- Automotive industry ( Mulhouse )

- Chemical industry ( Ottmarsheim ), oil refinery ( Reichstett )

- Biotechnology in the cross-border network Biovalley , the leading center of its kind in Europe

- tourism

- as well as other industrial and service sectors.

Economically, Alsace has a strong international focus: Companies from Germany , Switzerland , the USA , Japan and Scandinavia are involved in around 35% of the companies in Alsace . Numerous German companies such as Adidas , Schaeffler , Merck or Liebherr have branches or production sites in Alsace.

In 2002 around 38.5% of Alsatian imports came from Germany. While Alsace had low unemployment in the 1990s, this has changed since 2002 and even more so since the economic crisis since 2008. In the fourth quarter of 2019, the unemployment rate in Bas-Rhin was 6.8 and in Haut-Rhin at 7.8% (national average: 8.1%). This was mainly caused by the economic problems of the industrial companies, which employ around a quarter of Alsatians. The Alsatian economy is therefore trying to reorient itself and open up new fields of work in the service sector and in research.

In mining, a century some 560 million tons of potash has promoted, yet about 13,000 people were employed in 1950 in potash district . Today mining is only the subject of a museum near Wittelsheim .

Alsace is one of the largest European growing areas for white cabbage , which is processed into sauerkraut .

Since the Middle Ages, flax cultivation and linen weaving played an important role, especially in the Colmar area. The checked goblet is a typical Alsatian linen fabric .

traffic

Road network

The most important road connection in Alsace is the toll-free A 35 motorway , it is the north-south connection from Lauterbourg to St. Louis near Basel . A short stretch of the A 35 runs south of Strasbourg as a national road, with plans to close this gap.

The busy A4 leads from Strasbourg to Saverne and on to Paris . It is subject to toll from the toll station at Hochfelden (20 km northwest of Strasbourg). The A 36 leads from the German A 5 from the Neuchâtel motorway triangle to the west in the direction of Paris / Lyon and is subject to tolls from the toll station at Burnhaupt-le-Haut .

In the 1970s and 1980s, the highways were converted into transit routes and arterial roads for the major metropolitan areas. Since then, through traffic has been flowing in two to three lanes 1 km around Strasbourg and 1.5 km around Mulhouse. The high traffic density causes severe environmental pollution, especially on the A 35 near Strasbourg with 170,000 vehicles per day (as of 2002). The heavy city traffic on the A 36 near Mulhouse also regularly causes traffic delays. This could only be reduced temporarily by expanding to three lanes in each direction.

In order to take up the north-south through traffic and relieve Strasbourg, a new motorway route is planned west of the city. This route is to connect the motorway triangle at Hœrdt in the north with Innenheim in the south. The opening was scheduled for the end of 2011. A traffic volume of 41,000 vehicles per day is then expected. The benefits are controversial, however, according to some estimates, the new route will only take up 10% of the traffic volume of the A35 near Strasbourg.

In addition, due to the introduction of the truck toll in Germany in 2005, there is a considerable increase in the freight traffic previously driven on the German A 5 on the parallel and toll-free Alsatian motorway. Therefore, at the beginning of 2005, Adrien Zeller , the then President of the Alsace region , called for the German toll system Toll Collect to be extended to the Alsatian route.

Rail network

There is a rail network in Alsace that is connected to both high-speed and regional transport . Streetcars (trams) are found in Strasbourg ( Strasbourg tramway ) and Mulhouse ( Mulhouse tramway ).

In Alsace (and in the Moselle department in Lorraine), trains use the right-hand track on double-track connections, contrary to the rule otherwise applicable in France.

The Vosges tunnel from Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines (Markirch) to Saint-Dié was a railway tunnel until 1973. Since 1976 it has been reserved for road traffic as a toll route. The structure was closed from 2004 to 2008 to expand the safety devices and was reopened on October 1, 2008.

The rail network is still being expanded:

- LGV Est européenne from Paris to Strasbourg and on via the Europabahn to Stuttgart or Munich, as well as branching off via Saarbrücken to Frankfurt

- LGV Rhin-Rhône from Dijon to Mulhouse station and on in the direction of Basel and Freiburg

Waterways

Over 15 million tons of goods are handled in the Alsatian ports. Three quarters of this is in Strasbourg, which has the second largest inland port in France. The extension of the Rhine-Rhône Canal , which connects the Rhone and thus the Mediterranean with the Central European river network ( Rhine ) and thus the North Sea and the Baltic Sea , was in 1998 because of the costs and the destruction of the landscape, especially in the Doubs valley , set. The Canal de la Bruche was used until 1939.

Air traffic

There are two international airports in Alsace:

- the Strasbourg Airport (Aéroport International Strasbourg) in Entzheim southwest of Strasbourg

- the binational Basel-Mulhouse airport (EuroAirport Basel Mulhouse Freiburg) in Saint-Louis between Mulhouse and Basel

In 2011, both airports together had a total of 6,090,979 passengers.

Bike paths

Alsace has over 2000 kilometers of paved bike paths.

Three EuroVelo routes lead through Alsace:

- EV5: Via Francigena from London to Rome / Brindisi via the Saar Canal and the Rhine-Marne Canal

- the EV6: from the Atlantic to the Black Sea - from Nantes to Budapest via the Rhine-Rhône Canal

- EV15: Véloroute Rhin / Rhine Cycle Route from Andermatt (Switzerland) to Rotterdam

Smaller connections link Alsace with the neighboring Palatinate and Baden , including:

- the Pamina cycle route Lautertal (Itinéraire cyclable de la Lauter) from Lauterbourg to Dahn via Wissembourg

- Baden-Baden - Haguenau

- Offenburg (Baden Wine Route) - Molsheim (Alsace Wine Route) - Itinéraire cyclable européen (European cycle route) via Kehl - Strasbourg

- Elzach in the Black Forest - Villé in the Vosges via the Kaiserstuhl

All towpaths of the Alsatian canals ( Saar Canal , Rhine-Marne Canal , Breusch Canal , Rhine-Rhône Canal ) are paved. Many disused railway lines can be used as cycle paths, for example:

- Woerth - Lembach (former Maginot Line )

- Surbourg - Betschdorf and Hatten (Bas-Rhin) - Niederroedern

- 2.5 km west of Obermodern to before Bouxwiller and to Bouxwiller via Neuwiller-lès-Saverne to Dossenheim-sur-Zinsel

- Odratzheim - Westhoffen (former tram route from Strasbourg to Westhoffen)

- Romanswiller - Wasselonne - Marlenheim

- Marlenheim - Molsheim on the Alsatian Wine Route .

Culture

Languages and dialects

→ See also: Languages and dialects in Alsace , Alsatian , border towns of the Alemannic dialect area , Romance dialects in Alsace , Which

Germanic dialects have been at home in Alsace since the early Middle Ages . Today they are summarized under the term " Alsatian " (more rarely also "Alsatian German"). Among these, Alemannic dialects predominate, predominantly Upper Rhine- Alemannic , in the far south also High Alemannic . South Franconian dialects are spoken in the far north around Wissembourg and Lauterbourg and Rhine Franconian in the north-western corner of the Crooked Alsace around Sarre-Union. The use of a standard German language depended on political circumstances.

In the early Middle Ages, however, not all of today's Alsace was linguistically Germanized: Romanic dialects ( patois ) or the French language are therefore already traditional in some areas of the Vosges (upper Breuschtal, parts of the hamlet valley, around Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines and around Lapoutroie ) and anchored in the western Sundgau (around Montreux) (see Romanesque dialects in Alsace and border towns of the Alemannic dialect area ) . Today's Territoire de Belfort , which was part of the Habsburg or royal French Sundgau until 1648 or 1789 and was only separated from the Haut-Rhin department in 1871 , is traditionally Romansh or French-speaking.

French gradually gained in importance, especially between the 16th and 20th centuries. This was mainly due to the political history, in particular the consequences of the 30-year war, but also partly to the reputation that French enjoyed in the nobility and upper middle class across Europe , especially in the early modern period .

After the conquest by French troops 1639–1681, French came to Alsace with the royal administrators as well as immigrants and traders from central France. However, the majority of the population continued to use German or their respective Germanic or Romance dialect.

French spread throughout Europe, and even more so in Alsace, as the administrative, commercial and diplomatic language of the urban and rural elites. Otherwise, the Germanic (and Romance) Alsatian dialects and the German language were retained; at the University of Strasbourg, for example, teaching was still in German.

After the French Revolution , the language policy of the French state changed, which now advocated linguistic unity for France. In addition, French found its way into those sections of the population who sympathized with the ideas of the revolution. German or the German dialects were now part of a development towards partial bilingualism . In the areas of the patois, French prevailed because of the school lessons. As in other non-French-speaking regions of France or other minority regions of other European countries, the minority language, especially in schools, has increasingly been supplemented by or supplanted by the language of the majority.

During the affiliation to the German Empire ( Reichsland Elsaß-Lothringen , 1871-1918), the "language question" was initially regulated in a law of March 1872 so that the official language was basically German. However, in the parts of the country with a predominantly French-speaking population, public notices and enactments should be accompanied by a French translation. Another law of 1873 allowed the use of French as the language of business for those administrative units in which French predominated in whole or in part. In a law on education from 1873 it was regulated that in the German-speaking areas German was the exclusive school language, while in the French-speaking areas the lessons should be held exclusively in French. French-speaking communities and families in Alsace-Lorraine, like the Polish-speaking regions of Prussia, were exposed to attempts at Germanization and assimilation. French remained the school and official language there only partially.

The French language policy between 1918 and 1940 was strictly directed against the German language and the Alsatian dialect. The French language was introduced as the compulsory official and school language. Only French was allowed in schools and administration. However, from the November 1919 elections until the beginning of 2008, candidates from the three departments of Haut-Rhin, Bas-Rhin and Moselle were allowed to distribute campaign literature in both languages, French and German.

During the occupation by the Nazi state between 1940 and 1944, Alsace once again experienced an increase in restrictive language policy. This was ruthlessly adapted to the Nazi ideology . The conversion of French first names into German is certainly one of the more harmless but typical examples. The policy of the NSDAP and the civil administration that it ruled (oppression of the population, Germanization policy , grotesque anti-French cultural policy, entry into the Wehrmacht, etc.) sustainably promoted the turning away of Alsace from Germany.

After the Second World War, French became the lingua franca, official and school language. Knowledge and, above all, active use of the autochthonous Alemannic, South or Rhenish Franconian dialects (summarized in the term Alsatian ) or standard German are therefore strongly declining and increasingly limited to the older generation.

The French language policy of the pre-war period continued in principle, reinforced as a result of the experience of the occupation of France and the National Socialist terror, which led to everything German being viewed suspiciously or negatively. The older generations continued to communicate in Alsatian dialects, while the transmission , the passing on to the following generations, waned more and more - especially in the fear that the children had to learn "good French". While Alsatian retained its position as the language of the majority of the population in the first post-war decades, the transmission of Alsatian began to decline sharply from the 1970s. The younger generations, especially in the larger cities, use the French language more and more, in line with their schooling. In schools, German is mainly taught as a foreign language. It was not until the 1990s that measures were first taken to stop the decline in both the dialect and Standard German. In 1991 the first bilingual schools with both German and French as the language of instruction were founded. Since then, the number of students attending bilingual schools and kindergartens has risen continuously . In September 2003, bilingual schools in Alsace were attended by 13,000 students. In 2009, 17.1% of pre-primary and primary schools and 28.2% of secondary schools offered bilingual education.

While in France, which has been heavily researched in terms of statistics, there are no official surveys on “private matters” such as B. the mother tongue, surveys show that even in the third millennium, more than half of the population ascribes skills in the regional dialect to themselves. As the Strasbourg-based Office pour la Langue et Culture d'Alsace (OLCA, "Office for Language and Culture in Alsace") indicates, in 2013 43% (2001: 61%, 1997: 63%) of the respondents in a study named themselves as "dialect-speaking" (dialectophone) - that would correspond to around 800,000 inhabitants. These Alsatian speakers are most common in rural areas, in villages, and to a lesser extent in cities. In addition to these 43% Alsatian speakers, 33% said they spoke little and 25% said they had no knowledge of Alsatian. Even among the 18 to 29 year olds, 38% were Alsatian speakers in 1997; in 2012 it was only 12%.

Under the motto E Friehjohr fer unsi Sproch (“A spring for our language”), theater and music groups, dialect poets, local associations and language tutors have come together since 2001 to promote the preservation of Alsatian. The Regional Council also subsidizes Alsatian language courses. France 3 Alsace broadcasts the news program “Rund Um” from Monday to Friday, in which only Alsatian is spoken. There is a danger in the folklore of dialects, a tendency that can also be observed in German-speaking countries. The disappearance of German and the Alsatian dialects has become the subject of many well-known writers ( René Schickele , André Weckmann , Hans Arp and others).

In the political debate about the preservation of German, a clear preference has been set in favor of dialects and against standard German. The focus is less on Switzerland , where dialect and the associated standard language coexist ( diglossia ), but more on language models such as Luxembourg , where the dialect is valued more highly than the associated standard language and is even expanded into a written language . In Strasbourg , for example, in connection with the documentation of German street names on street signs, after a long discussion it was decided not to use standard German, but instead to use the Strasbourg dialect. The problem with the higher valuation of the dialects compared to the associated standard language is that dialects also show strong regional and social differences in Alsace. The survival of the dialects may then also depend on the extent to which a “standard Alsatian” is or can be established.

The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages , signed by the French government in 1992, has not yet been ratified by the French parliament (as of 2015) and is therefore still not legally valid in France.

In Alsace today (as of 2010), German is learned as a foreign language by 48.1% of children in pre-school and 91.1% of children in primary school. In the middle school it is still 73.2%, in the grammar school (Lycée) then 15.4%. These are all values well above the French average. A quarter of all AbiBac degrees in France are also obtained in Alsace. Nevertheless, from the point of view of the education authority, the track record is mixed. It is true that 10% of kindergarten pupils start to take German lessons on an equal footing, but of the initial 19,000 pupils only 3500 are left in the college . In the grammar school there are only less than 1000 students. In addition, there is a shortage of teachers, which one wants to combat through cooperation with German schools. A total investment of one million euros is planned to promote German-language teaching. The effort also includes an advertising campaign for the German language. Politicians support this, as only around 1% of first graders spoke Alsatian and since 2005 the Alsatians have not been able to apply for 10,000 jobs because they lack language skills.

Religions

Alsace was Christianized in the 5th century and produced a number of important churches and monasteries in the Middle Ages. In the Reformation , Alsace played a major role through personalities such as Martin Bucer , and the imperial city of Strasbourg became a center of the Reformation in southwest Germany, but most of Alsace remained Catholic except for a few territories. Other cities in Alsace also became strongholds of the Reformation before 1530: Haguenau , Mulhouse , and possibly Wissembourg .

The Christian denominations in Alsace have retained their historical ties to the state to this day. Unlike in the rest of France, where state and church were separated in 1905, the parishes still receive subsidies for pastors' salaries from the state as a state benefit due to the Napoleonic so-called organic articles . The Protestant Church of the Augsburg Confession of Alsace and Lorraine belongs with the Reformed Church of Alsace and Lorraine to the independent Union of Protestant Churches of Alsace and Lorraine . The same status, which thus reflects the status of the Napoleonic Concordat of 1801 , applies to the Alsatian parishes of the Roman Catholic Church in France .

Altogether around 70% of the population in Alsace are Catholic, 17% Protestant (most of them Lutherans , the rest mostly Reformed ), and 5% belong to other religions. This is the highest percentage of Protestants in any French region today. Until they were ousted in the Thirty Years' War , the Anabaptists had a strange presence in Alsace. Historically, the Jewish communities were well represented, especially when compared to inner France. This was due to the fact that the Jews were completely expelled from France as early as the Middle Ages , while they were able to assert themselves in Alsace, which at that time belonged to the Holy Roman Empire and only came to France much later. In the years 1940–44, many Alsatian Jews were deported and murdered; since the 1960s, many Sephardic Jews from North Africa settled in Strasbourg, and they revitalized the communities. Organizationally, the Jewish communities are represented by the consistory for the Upper Rhine and Lower Rhine . In the meantime, Muslims are also strongly represented here, especially by immigrants from Turkey and the Maghreb . This makes Alsace the “most religious part of France”.

to eat and drink

The Alsatian cuisine is known for some culinary specialties. These include:

- Flammkuchen (tarte flambée) (Alsatian: Flammekuech - "ue" pronounced as üe or ö )

- Gugelhupf (yeast bowl cake) (in Alsace: Kugelhopf; Alsatian: Köjelhopf , French often Kouglof )

- Choucroute (Sauerkraut) (Alsatian: Sürkrüt )

- Baeckeoffe ("baker's oven": stew made from meat, potatoes and leek, the Alsatian main course)

- Schiffala (smoked pork shoulder, Schäufele )

- Bredele ("bread roll": butter cookies with cinnamon and nuts)

- Mignardises (sweet tartlets)

- Friands (sweet pastry pies)

- Birewecke (fruit bread with pears)

- Crémant d'Alsace (Alsatian sparkling wine)

- Quetsch d'Alsace ( plum water ), which is produced in house distilleries in two distilleries due to old (Alsatian / German) rights with an alcohol content of over 50% (compare the French article)

- Tarte aux pommes (Alsatian apple pie) (Alsatian: Äpfelwaia )

- Tarte aux quetsches (plum cake) (Alsatian: Zwatschgawaia )

- Galettes de pommes de terre (small potato pancakes): (Alsatian Grumbeerekiechle ., Literally "Grundbirnenküchlein" Even in the Palatine dialects they say Grumbeere or Grumbiere According to the Austrian for "potato"), Erdapfel and the North German Drake .

- Tarte à l'oignon (Alsatian onion cake) (Alsatian: Zwiwwelkuech )

- Coq au Riesling (Coq au Vin "Rooster in Wine"; using Alsatian Riesling )

- Foie gras (pie from the liver of stuffed goose or duck)

- Munster ( Munster cheese; intense tasting, creamy cheese with reddish rind ) (Alsatian: Minschterkas )

Sports

Racing Strasbourg's footballers played for many years in Ligue 1 , the top division of French football, and were even among the top teams there at the end of the 1970s. In 1979 the club became French champions for the first and only time so far . Most of the clubs in Alsace have their roots in previous German clubs due to its changeful history. For example, Racing Strasbourg was founded in 1906 as FC Neudorf .

Newspapers, magazines, periodicals

-

Dernières Nouvelles d'Alsace (DNA) , online edition of the daily newspaper (French)

- DNA (German)

- DNA, France edition (French)

- DNA, international edition (French)

Well-known Alsatians

See also

- List of important churches in Alsace

- Bibliothèque Alsatique

- Elsgau

- Cette histoire qui a fait l'Alsace

Filmography

- The Alsatians . Feature film, France, 1996, with Irina Wanka and Sebastian Koch , among others

- Picture book Germany . Alsace - The southern wine route. Documentation, 2007, 45 min., Script and direction: Willy Meyer, production: SWR , first broadcast: June 17, 2007, summary ( memento from September 25, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) by ARD

- Picture book Germany. Alsace - The Northern Wine Route. Documentation, 2008, 45 min., Script and direction: Willy Meyer, production: SWR, first broadcast: March 9, 2008, summary ( memento from September 25, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) by ARD

- The linden trees of Lautenbach . TV movie, France / BR Germany 1982, directed by Bernard Saint-Jacques, with Mario Adorf . Based on the book by Jean Egen.

literature

- Modern monographs and treatises

- Alsace. A literary travel companion . Insel, Frankfurt 2001, ISBN 3-458-34446-2 .

- Michael Erbe (Ed.): The Alsace. Historical landscape through the ages . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-17-015771-X .

- Gustav Faber: Alsace (= Artemis-Cicerone art and travel guide ). Artemis, Munich / Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-7608-0802-6 .

- Christopher F. Fischer: Alsace to the Alsatians? Visions and Divisions of Alsatian Regionalism, 1870-1939. Oxford-New York: Berghahn 2010.

- Robert Greib, Frédéric Hartweg, Jean-Michel Niedermeyer, François Schaffner: Language & Culture in Alsace: A Story. Salde-Verlag, Strasbourg 2016, ISBN 978-2-903850-40-1 .

- Frédéric Hartweg: Alsace. The stumbling block and touchstone of Franco-German relations . In: Robert Picht et al. (Ed.): Strange friends. Germans and French before the 21st century . Piper, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-492-03956-1 , pp. 62-68.

- Marianne Mehling (Ed.): Knaur's cultural guide in color Alsace . Droemer Knaur, Munich 1984.

- Hermann Schreiber: Alsace and its history, a cultural landscape in the tension between two peoples . Katz, Gernsbach 1988, ISBN 3-925825-19-3 ; NA: Weltbild, Augsburg 1996.

- Bernard Vogler: A Little History of Alsace . DRW-Verlag, Leinfelden-Echterdingen 2010, ISBN 3-7650-8515-4 .

- Rudolf Wackernagel : History of Alsace , Frobenius, Basel 1919, OCLC 10841604 .

- Bernard Wittmann: Alsace, Une langue qu'on assassine, Livre noir du jacobinisme scolaire en Alsace.

- Jean-Michel Niedermeyer: The places of one language. Alsatian language from 1789 in pictures and caricatures . SALDE-Verlag, 2020, ISBN 978-2-903850-62-3 .

- Older representations

- Johannes Friese: New Patriotic History of the City of Strasbourg and the former Alsace. From the oldest times up to the year 1791 . Volumes 1–2, 2nd edition, Strasbourg 1792 ( books.google.de )

- Adam Walther Strobel, Heinrich Engelhardt: Patriotic history of Alsace from the earliest times to the revolution in 1789, continued from the revolution in 1789 to 1813 .

- First part. Second edition. Strasbourg 1851 ( books.google.de ).

- Volume 2, Strasbourg 1842 ( books.google.de )

- Volume 3, Strasbourg 1843 ( books.google.de ), 2nd edition, continued from the revolution from 1789 to 1815, by L. Heinrich Engelhardt, Strasbourg 1851 ( books.google.de )

- Fourth part, Strasbourg 1844 ( books.google.de ).

- Fifth part. Second edition. Strasbourg 1851 ( books.google.de ).

- Sixth part. Second edition. Strasbourg 1851 ( books.google.de ).

- Johann Friedrich Aufschlager: The Alsace. New historical-topographical description of the two Rhine departments .

- Volume 1, Johann Heinrich Heitz, Strasbourg 1825 ( books.google.de )

- Volume 2, Johann Heinrich Heitz, Strasbourg 1825; archive.org

- Volume 3: Supplement , Johann Heinrich Heitz, Strasbourg 1828; archive.org

- Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl : Alsatian culture studies . In: Historical paperback . Fifth episode, first year, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1871, pp. 1–64.

- The history of Alsace. A book for school and home . R. Schultz and Co. (Berger-Levrault's Nachf.), Strasbourg 1879 ( books.google.de )

- Statistical office of the Imperial Ministry for Alsace-Lorraine: Local directory of Alsace-Lorraine. Compiled on the basis of the results of the census of December 1, 1880 . CF Schmidts Universitäts-Buchhandlung Friedrich Bull, Strasbourg 1882; archive.org .

- Alsace-Lorraine. In: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition. Volume 6, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1906, pp. 725–736 .

Web links

- Link catalog on Alsace at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Literature on Alsace in the catalog of the German National Library

- Regional culture. alsace-culture.com

- Rolf Müller: Memories of a time when oil was drilled in Alsace badische-zeitung.de , April 7, 2018 ( musee-du-petrole.com Musée Français du Pétrole )

- Alsace: in the heart of Europe ´. france.fr

- Visit Alsace , the official Alsace tourism website

- Christiane Kohser-Spohn: The dream of a common Europe. Autonomy movements and regionalism in Alsace 1870–1970 (PDF, 4.3 MB) Herder Institute (Marburg) , 2003. In: Philipp Ther , Holm Sundhaussen (Ed.): Regional movements and regionalisms in European spaces since the middle of the 19th century. Century , pp. 89–112

Individual evidence

- ^ Dictionary of Alsatian dialects . Volume I, p. 34.

- ↑ It was initially named Alsace-Champagne-Ardenne-Lorraine; see France: The border region is to be called Grand Est in the future . orf.at, April 4, 2016; Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ Report on vie-publique.fr of June 27, 2019

- ^ Report of the Direction de l'information légale et administrative. vie-publique.fr

- ↑ a b c Alsace . In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Volume 7. pp. 175-177.

- ↑ miserable . In: Etymological dictionary of the German language . 18th edition, edited by Walther Mitzka. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1960, p. 163.

- ^ Geology of Alsace . Lithothèque d'Alsace website (French).

- ↑ More detailed Reinhard Stupperich : Alsace in Roman times . In: Michael Erbe (Ed.): The Alsace . Pp. 18-28.

- ↑ Gerhard Ritter, Staatskunst und Kriegshandwerk I, The Old Prussian Tradition, p. 287

- ↑ Bernard Vogler: Small history of Alsace . DRW-Verlag, Leinfelden-Echterdingen 2010, ISBN 3-7650-8515-4 , p 160

- ↑ Law on the Constitution of Alsace-Lorraine of May 31, 1911 (full text)

- ↑ see also Stefan Fisch: Nation, 'Heimat' and 'petite patrie' in Alsace under German rule 1870 / 71–1918. In: Marco Bellabarba, Reinhard Stauber (ed.): Identità territoriali e cultura politica nella prima età moderna (= territorial identity and political culture in the early modern period), Bologna / Berlin 1998, pp. 359–373.

- ↑ Article 27, paragraph 3

- ↑ See chap. 5 in Christopher J. Fischer: Alsace to the Alsatians? Visions and Divisions of Alsatian Regionalism, 1870-1939 . 2010 (hardcover), 2014 ( ISBN 978-1-78238-394-9 ). Both from Berghahn Books

- ^ Antonio Elorza: Alsace, South Tyrol, Basque Country (Euskadi): Denationalization and Identity . In: Georg Grote , Hannes Obermair (Ed.): A Land on the Threshold. South Tyrolean Transformations, 1915-2015 . Peter Lang, Oxford-Bern-New York 2017, ISBN 978-3-0343-2240-9 , pp. 307-325, here: p. 319 .

- ↑ olcalsace.org

- ↑ schwarzwaelder-bote.de

- ^ Manifestation à Strasbourg pour une Alsace sans la Lorraine. In: Liberation.fr , October 11, 2014; Olivier Mirguet: Contre la fusion des régions, l'Alsace défile et caricature la Lorraine. In: L'Express .fr , October 11, 2014.

- ↑ Eurométropole de Strasbourg ( French ) Direction générale des collectivités locales. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ "Les Accords de coopération entre l'Alsace et ..." ( Memento of March 9, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), region-alsace.eu , January 20, 2009

- ↑ Eurostat press release 63/2006 (PDF; 580 kB)

- ↑ journaldunet.com

- ^ Parliamentary question from Jean-Louis Masson, Member of the Moselle Department, dated December 9, 1991 to the French Minister of the Interior

- ↑ 20minutes.fr

- ↑ lexpress.fr

- ↑ Histoire de la langue . olcalsace.org; Retrieved April 14, 2014

- ↑ a b aplv-languesmodernes.org (PDF)

- ↑ ABCM bilingualism. Association pour le Bilinguisme en Classe dès la Maternelle

- ↑ Le dialecte en chiffres

- ↑ Alsace wants to learn more German . In: Badisches Tagblatt

- ↑ Géographie RELIGIEUSE France. ( Memento of the original from August 1st, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. eurel.info

- ↑ The film consists of four episodes of 90 minutes each and tells the story of Alsace between 1870 and 1953 using stories from fictional families

- ↑ Alsatian impressions from fifty writers from five centuries

Coordinates: 48 ° 15 ' N , 7 ° 32' E