Romance languages

| Romance languages | ||

|---|---|---|

| speaker | approx. 700 million | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| ISO 639 -5 |

roa |

|

The Romance languages belong to the (modern) Italian branch of the Indo-European languages . The group of Romance languages offers a special feature in that it is a language family whose common precursor language was Latin (or Vulgar Latin ), which can be proven in its history and written traditions. There are around 15 Romance languages with around 700 million native speakers, 850 million including second speakers. The most widely spoken Romance languages are Spanish , Portuguese , French , Italian and Romanian .

History of the linguistic classification of the Romance languages

One of the first to classify and write about the Romance and other European languages was Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada with his History of the Iberian Peninsula from 1243 De rebus Hispaniae . De Rada distinguished three major groups, which he divided into the Romance, Slavic and Germanic languages; he also mentioned other languages, such as Hungarian and Basque . In the Spanish Renaissance , Andrés de Poza (1587) wrote down the first classification of the Romance languages. It was an overview of the Romance languages, which also included Romanian and retained their meaning until the 18th century.

The general development, which began in the 16th century, continued to advance. Joseph Justus Scaliger arranged languages into a Romance, Greek, Germanic and Slavic family, Georg Stiernhielm specified and expanded this classification. Sebastian Münster recognized a relationship between Hungarian, Finnish and Sami. Claudius Salmasius showed similarities between the Greek and Latin and the Iranian and Indian languages.

In Germany , Friedrich Christian Diez, with his "Grammar of Romance Languages" from 1836, is considered the founder of academic Romance studies. Diez wrote scientific works on Provencal literary history, such as "The Poetry of the Troubadours" (1826), "The Life and Works of the Troubadours" (1829). In his comparative grammar of the Romance languages - published as a three-volume work between 1836 and 1844 - he stated that all Romance languages go back to Vulgar Latin. His students in Bonn included u. a. Hugo Schuchardt , Gaston Paris and Adolf Tobler . In 1876 he was succeeded by Wendelin Foerster at the University of Bonn . In 1878 he founded the “Royal Romanesque Seminary” as the first university institute for this discipline. He, too, devoted himself to researching the languages that developed from Latin.

History of the Romance Languages

In contrast to most other language groups, the original language of Romansh is well documented: It is the spoken Latin of late antiquity (folk or vulgar Latin ). Latin itself is not considered a Romance language, but is counted together with the Oscar - Umbrian language to the Italian languages , of which only Latin today still has "descendants", namely the Romance languages.

The Romanization began as spread of the Latin language in by the Roman Empire administered territories. This spatial expansion peaked around AD 200.

The areas in which there are only relics or indirect evidence of Latin such as place names are called Romania submersa ("submerged Romania"); Romania continua is used in connection with the part of Europe that is still Romansh- speaking today. With Romania nova ( "new Romania") that region is called, in which a Romance language only through the modern colonization has come.

While the ancient Indo-European languages that developed from the original Indo-European language, such as Sanskrit and then, to a lesser extent, Greek and Latin, were from a synthetic language structure , the development of vulgar Latin dialects and languages increasingly led to an analytical language structure . This change had far-reaching consequences. While in more or less pure synthetic languages the word order is free and thus ensures flexible expression, in the analytic languages the relationships must be expressed through word orders. For this purpose, in the course of this turn to the analytical structure of the Romance languages , the speakers created articles before the nouns, personal pronouns before the verbs, introduced auxiliary verbs into the conjugation, replaced the case with prepositions and introduced adverbs to compare the adjectives and much more.

Morphologically , the Romance verbs have retained the use of word forms in many respects, but also show a tendency towards analytical formations in many places. In the morphology of nouns, however, the development was different, there was a far-reaching loss of the case - a development that can already be traced in Vulgar Latin, where Latin case endings were regularly replaced by prepositions.

This development towards the Romance languages resulted in a completely different syntax . Although the verb forms are still strongly marked , i.e. the predicate retained its compact position, the syntactic relationships between the clauses were no longer expressed by the case, but by prepositions and the more rigid word order. This made the sentence order rules simpler for the speaker , because syntactically related units remain next to each other.

Today's standard languages

Today's standard Romance languages are:

| language | Native speaker | distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Spanish (español, castellano) | 388,000,000 | Spain , Mexico , Central and South America (excluding Brazil, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, Belize), Equatorial Guinea , Western Sahara and parts of the United States and the Philippines . |

| Portuguese (português) | 216,000,000 | Portugal , Brazil , Angola , Equatorial Guinea , Mozambique , East Timor , Cape Verde , Guinea-Bissau , São Tomé and Príncipe , Macau |

| French (français) | 110,000,000 | France , Belgium ( Wallonia ), western cantons ( Romandie ) of Switzerland , Antilles , Canada (especially Québec , parts of Ontario and New Brunswick / Nouveau-Brunswick ), United States of America in the state of Louisiana , in former French and Belgian colonies in Africa (especially Ivory Coast and DR Congo ) |

| Italian (italiano) | 65,000,000 | Italy , Switzerland ( Ticino and southern Graubünden ), San Marino , Vatican City , Croatia ( Istria County ), Slovenia ( Koper , Piran , Izola ) |

| Romanian (română) | 28,000,000 | Romania , Moldova , Serbia ( Vojvodina and Timočka Krajina ) and other countries in Eastern Europe and Western Asia (including Ukraine and Israel ) |

| Catalan (català) | 8,200,000 | Catalonia including Roussillon (southern France ), Andorra , Balearic Islands , Valencia , Franja de Aragón and Sardinia in the city of L'Alguer / Alghero |

| Venetian (vèneto) | 5,000,000 | Veneto ( Italy ), Friuli-Venezia Giulia , Trentino , Istria and in Rio Grande do Sul ( Brazil ) |

| Galician (galego) | 3,000,000 | Galicia (Spain) |

| Occitan ( Occitan ) | 2,800,000 | southern third of France , peripheral areas of Italy ( Piedmontese Alps) and Spain ( Val d'Aran in Catalonia) |

| Sardinian (sardu) | 1,200,000 | Sardinia ( Italy ) |

| Furlanic (furlan) | 350,000 | Friuli ( Italy ) |

| Asturian (asturianu) | 100,000 | Asturias (Spain) |

| Bündnerromanisch (Romansh; Rumantsch / Romontsch ) | 60,000 | Graubünden ( Switzerland ) |

| Ladin (ladin) | 40,000 | Italy ( South Tyrol , Trentino , Veneto ) |

| Aragonese (aragonés) | 12,000 | Aragon (Spain) status as a standard disputed |

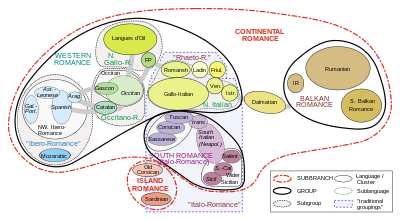

Romance languages by subgroup

The Romance languages can be divided into several subgroups according to partly system linguistic, partly geographical criteria. In the following list of Romance languages, it should be noted that it is difficult to list many Romance idioms , as they are sometimes listed as independent languages, sometimes as dialects , depending on the source . This is due to the fact that they do not have a uniform standard language , but are mainly used alongside another standard language, especially in informal contexts ( diglossia ).

With the exception of Sephardic and Anglo-Norman, the linguistic forms listed here are language forms that have developed directly and in unbroken temporal continuity from spoken Latin. With the exception of Romanian, they also form a spatial continuum in Europe . Due to the temporal and spatial continuity, one also speaks of the Romania continua .

The most important distinction among the Romance languages in the field of historical phonology and morphology is that between Eastern and Western Romance languages . For West Romanesque the whole are Ibero-Romance and Gallo-Roman and the northern Italian varieties and Romansh languages ( Romansh , Ladin and Friulian ) expected; for East Romance the Italian (with the exception of North Italian varieties ) and the Balkan Romance . The Sardinian is usually quite exempt from this distinction, as it can be clearly assigned to either group.

Ibero-Romance languages

For Ibero Romanesque include the Spanish , the Portuguese and the Galician Language (the latter are sometimes a slide system together). The position of Catalan spoken in the north-east of the Iberian Peninsula (including Valencian ) is controversial; it occupies a transition position between Ibero-Roman and Gallo-Roman. The Ibero-Romance languages also include:

- Aragonese in the north of the Aragon region in Spain

- Asturleonese in the Asturias region and the provinces of León and Zamora in Spain. Closely related to this is Mirandesian (Mirandés) in northeastern Portugal, which is the local official language there.

- Jewish Spanish or Ladino, the language of the Sephardi expelled from Spain after 1492 , is still spoken today in Turkey , Israel and New York .

Gallo-Roman languages

The standard French language is used today in almost all of the Gallo-Roman languages . According to system linguistic criteria, the Gallo-Roman languages can be divided into three groups:

-

Langues d'oïl . In addition to French, these include several dialects that are more closely related to it, which are also viewed by some as separate languages:

- Picard in northern France and Belgium

- Walloon in north-eastern France and Belgium

- Anglo- Norman, the language of the Norman upper class in medieval England after 1066

- Norman in north-west France and the Channel Islands ( Jèrriais on the island of Jersey , Dgèrnésiais on the island of Guernsey and Sercquiais on the island of Sark )

- Gallo in the eastern part of Brittany

- Angevin in western France

- Lorraine in the Lorraine departments of Moselle , Meurthe-et-Moselle and Vosges , a sub-dialect is which in Alsace .

- Franco-Provencal . This term the dialects of the center are of linguists Rhone valley , the greater part of the French-speaking Switzerland ( Romandie ), Savoy and the Aosta valley summarized. However, there is no standard language or independent language awareness; French has been used as the written language here from time immemorial.

-

Occitan or Langue d'oc in southern France ( Occitania ), the Alps of northwest Italy and the Val d'Aran in Catalonia . Due to the system spacing, this must be classified as an independent Romance language in any case, but does not have a generally recognized standard variety:

- Auvergnatisch in the Auvergne

- Gaskognisch in southwest France between the Garonne and the Pyrenees as well as in the Val d'Aran ; in the Val d'Aran the local variety, Aranese , is the local official language.

- Languedoc in the Languedoc

- Limousin in the Limousin

- Nissart in the area around Nice (is often counted as part of the Provençal)

- Provencal in Provence (the term Provençal was also used earlier for Occitan as a whole)

The distinction between Gallo-Romanic and Iberor-Romanic and Italian-Romanic within the Romance dialect continuum is not clear. The Catalan occupies a transitional position between Gallo-Roman and Iberoromanisch that Gallo Italian varieties are purely systemlinguistisch considered more in common than with the rest of Italo Romanesque to which they are usually counted for geographical and cultural and historical reasons, the Gallo-Roman. The close connection with the Romansh of today's France becomes clear, for example, in the Gallic / Celtic relic words of Gallo-Italian , most of which can also be found in the Celtic relic vocabulary of the Transalpina.

Romansh languages

The term Alpine or Rhaeto-Romanic languages is often used to summarize Furlanic , Graubünden Romance and Ladin . They were, as it were, isolated from the Gallo-Italian idioms when their speakers increasingly orientated themselves towards the Central Italian dialects.

Italo-Romance languages

The only standard Italian-Romance language is Italian . With the exception of Corsican and Monegasque, the remaining Italian-Romanic languages all belong to the scope of the standard Italian language and are therefore often classified as "Italian dialects". They can be divided into three subgroups, between which there are major differences:

- The varieties of the northern group partly assume a transitional position to Gallo-Roman . Those who have more in common with it in the field of sound development, morphology and vocabulary than with the rest of Italo-Romanic are therefore also summarized as Gallo-Italian . The Venetian Romansh in northeastern Italy, however, has more in common with the rest of the Italian Romansh . Belong to the northern group

- as Gallo-Italian varieties:

- Emilian in Emilia-Romagna

- Ligurian in Liguria ; a Ligurian variety is also the Monegasque in Monaco

- Lombard in Lombardy and southern Switzerland

- Piedmontese in Piedmont ,

- as Gallo-Italian varieties:

- such as:

- Venetian or Venetian Romance, in the Veneto region of northeast Italy.

- Central Italian varieties ( dialetti centrali ) are spoken in the regions of Tuscany and Umbria and for the most part in Lazio and Marche . The border to the northern Italian varieties roughly follows the line La Spezia - Rimini , the border to the southern Italian varieties of the line Rome - Ancona . They form the basis of the standard Italian language . The Corsican in Corsica , which has acquired there in addition to the French and to a limited extent official recognition belongs systemlinguistisch also considered the central Italian varieties, however, for geographical and cultural and historical reasons a special status.

- The southern Italian varieties ( dialetti meridionali ) are spoken in the southern half of the Apennine Peninsula and in Sicily . The best known are the Neapolitan in Campania and some neighboring regions, the diverse and for standard Italian speakers practically incomprehensible Calabrian dialects in Calabria and the Sicilian in Sicily.

- The Istriotische is in the southwest of Istria spoken and, together with the extinct Dalmatian language be included among the group of dalmatoromanischen languages.

Sardinian

The Sardinian in Sardinia cannot be assigned to any of the subgroups. It does not currently have a uniform standard language, but due to its system difference to the other Romance languages it must be classified as an independent language in any case. Due to the cultural and linguistic Italianization of the Sardinians since the late 18th century, the language is nevertheless very endangered.

Balkan Romance languages

Romanian is the only standard language belonging to the Balkan-Romance language group (the dialects covered by the Romanian written language are also summarized as Dacorumanian ). In the Republic of Moldova , too , following a constitutional amendment, the official language is again Romanian instead of Moldovan .

The group of Balkan Romance also includes several small languages spoken in Southeast Europe:

- Aromanian (also Macedorumanian ) in northern Greece , North Macedonia , Albania , Kosovo

- Istrian Romanian in northeastern Istria ( Croatia )

- Megleno-Romanian in the upper Meglen level on the border between Greece and North Macedonia .

Extinct Romance languages

Romance languages that are now extinct ( Romania submersa , submerged Romania) are:

- Dalmatian on the eastern Adriatic coast (with the variants Vegliotic on the island of Krk (Italian: Veglia ) and Ragusa around Dubrovnik (Italian: Ragusa ))

- Mozarabic (in Spain between the Arab conquest and the Reconquista )

- North African Romansh

- Moselle Romance language (Romance language island in the Moselle valley )

Creole languages based on Romansh

Some linguists also count the Romance-based pidgins and Creole languages as Romance languages. These "neo-Romanic languages" (Romania nova) can be divided into:

- Lingua franca (pidgin)

- french-based creole languages

- Spanish-Portuguese-based creole languages

Language comparison

The following example sentences show grammatical and word similarities within the Romance languages or between them and Latin:

Classical Latin (Ea) semper antequam cenat fenestram claudit. Classical Latin claudit semper fenestram antequam cenat. Vulgar Latin (Illa) semper fenestram claudit ante quam cenet. Latin in "Romanic sentence structure" (Illa) claudit semper fenestram ante quam cenet (or: ante cenam = before the meal). Andalusian (Eya) ziempre zierra la bentana antê de zenâh. Aragonese (Ella) zarra siempre a finestra antes de cenar. Aromatic (Ea / Nâsa) încljidi / nkidi totna firida ninti di tsinâ. Asturian (Ella) pieslla siempres la ventana enantes de cenar. Ayisyen Li toujou ap fèmen nan dat fennèt la devan manje. Bergamasco (Eastern Lombard ) (Lé) la sèra sèmper sö la finèstra prima de senà. Bolognese (dialect of Emilian ) (Lî) la sèra sänper la fnèstra prémma ed dsnèr. Bourbonnais (dialect) All the farm terjou la croisée devant de souper. Bourgogne - Morvandiaux All farms tôjor lai fenétre aivan de dîgnai. Emilian (Lē) la sèra sèmpar sù la fnèstra prima ad snàr. Extremadurian (Ella) afecha siempri la ventana antis de cenal. Frainc-Comtou Lèe çhioûe toûedge lai f'nétre d'vaïnt loù dénaie. Franco-Provencal (Le) sarre tojors la fenètra devant de goutar / dinar / sopar. Valais Franco-Provencal (Ye) hlou totin a fenetre deant que de cena. French Elle ferme toujours la fenêtre avant de dîner / souper. Furlanic (Jê) e siere simpri il barcon prin di cenâ. Galician (Ela) pecha / fecha semper a fiestra / xanela antes de cear. Gallo Ol barre terjou la couésée avant qhe de hamer. Idiom neutral Ila semper klos fenestr ante ke ila dine. Italian (Ella / Lei) chiude semper la finestra prima di cenare. Interlingua Illa claude semper le fenestra ante (de) soupar. Jews Spanish Eya serra syempre la ventana antes de senar. Catalan (Ella) semper tanca la finestra abans de sopar. Corsican (Ella / Edda) chjode semper u purtellu nanzu di cenà. Ladin (Ëra) stlüj dagnora la finestra impröma de cenè. (badiot) (Ëila) stluj for l viere dan maië da cëina (gherdëina) Latino sine flexione Illa claude semper fenestra antequam illa cena. Leonese (Eilla) pecha siempre la ventana primeiru de cenare. Ligurian (Le) a saera semper u barcun primma de cenà. Lingua Franca Nova El semper clui la fenetra ante cuando el come. Lombard (West) (Lee) la sara sù semper la finestra primma de disnà / scenà. Magoua dialect ( Quebec ) (Elle) à fàrm toujour là fnèt àvan k'à manj. Milanese dialect (dialect of Lombard ) (Le) la sara semper sü la finestra prima de disnà. Morisyen Li touzur pou ferm lafnet avan (li) manze. Mirandesian (Eilha) cerra siempre la bentana / jinela atrás de jantar. Mozarabic Ella cloudet semper la fainestra abante da cenare. (reconstructed) Neapolitan Essa nzerra sempe 'a fenesta primma' e magnà. Norman Ol barre tréjous la crouésie devaunt de daîner. Occidental Ella semper clude li fenestre ante supar. Occitan (Ela) barra semper / totjorn la fenèstra abans de sopar. Picard language Ale frunme tojours l 'creusèe édvint éd souper. Piedmontese Chila a sara sèmper la fnestra dnans ëd fé sin-a / dnans ëd siné. Portuguese Ela fecha semper a janela antes de jantar / cear. Roman (city dialect of Rome ) (Quella) chiude semper 'a finestra prima de magnà. Romanian (Ea) închide întotdeauna fereastra înainte de a lua cina. Romansh Ella clauda / serra adina la fanestra avant ch'ella tschainia. Sardinian Issa sèrrat sémper / sémpri sa bentàna innantis de chenàre / cenài. Sassarean Edda sarra sempri lu balchoni primma di zinà. Sicilian Idda chiui sempri la finestra prima di pistiari / manciari. Spanish (Ella) siempre cierra la ventana antes de cenar. Umbrian Essa chjude semper la finestra prima de cena '. Venetian Eła ła sara / sera semper ła fenestra vanti de xenàr / disnar. Walloon Ele sere todi li finiesse divant di soper. translation She always closes the window before she has dinner. Translation with changed syntax

(wrong in German)Always before she has dinner, she closes the window.

The following overview also shows similarities, but also differences in vocabulary, using a few sample words.

| Latin (noun in nominative and accusative) | French | Italian | Spanish | Occitan | Catalan | Portuguese | Romanian | Sardinian | Corsican | Franco-Provencal | Galician | Romansh | Ladin | Furlanic | German translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| clavis / clavem | clé , more rarely: clef | chiave | llave | clau | clau | chave | cheie | crae | chjave / chjavi | clâ | clave | clever | key | ||

| nox / noctem | nuit | notte | noche | nuèch (nuèit) | nit | noite | noapte | notte | notte / notti | nuet | noite | not | night | ||

| cantare | chanter | cantare | cantar | cantar (chantar) | cantar | cantar | cânta (re) | cantare | cantà | chantar | cantar | chanter | to sing | ||

| capra / capram | chèvre | capra | cabra | cabra (chabra, craba) | cabra | cabra | capră | cabra | capra | cabra / chiévra | cabra | chevra | cioura | goat | |

| lingua / linguam | langue | lingua | lengua | lenga | llengua | língua | limbă | limba | lingua | lenga | lingua | lingua | language | ||

| platea / plateam | place | piazza | plaza | plaça | plaça | praça | piață | pratza , pratha | piazza | place | place | plazza | space | ||

| pons / pontem | pont | ponte | puente | pont (pònt) | pont | ponte | punte (only wooden bridge) | ponte | ponte / ponti | pont | ponte | punt | punt | bridge | |

| ecclesia / ecclesiam | église | chiesa | iglesia | glèisa (glèia) | església | igreja | biserică (Latin basilica) | creia , cresia | ghjesgia | églésé | igrexa | baselgia | church | ||

| hospitale / hospitalis | hôpital | ospedals | hospital | espital (espitau) | hospital | hospital | hospital | ispidale | spedale / uspidali | hèpetâl | hospital | ospidel | hospital | ||

|

caseus / caseum Vulgar Latin formaticum |

fromage | formaggio (rarely cacio ) | queso | formatge (hormatge) | formatge | queijo | caș (cheese) / brânză (salty cheese) | casu | casgiu | tôma / fromâjo | queixo | hash oil | cheese |

Planned languages partly based on Romansh

Most of the planned languages are a reformed Romance language or a synthesis of several Romance languages. The so-called naturalistic direction is just such planned languages. The best-known and most important example is the Latino sine flexione from 1903 or the later Interlingua from 1951. But the so-called autonomous Esperanto also has its vocabulary for more than three quarters from the Latin and Romance languages, especially French.

See also

- Romanesque palatalization

- Pan-romance

- Quantity collapse

- Romania (linguistics)

- Société de Linguistique Romane

literature

Comprehensive scientific works

- Georg Bossong : The Romance Languages. A comparative introduction. Buske, Hamburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-87548-518-9 (+ 1 CD)

- Martin Harris, Nigel Vincent (Eds.): The Romance Languages. Routledge, London 2000, ISBN 0-415-16417-6 (EA London 1988).

- Harri Meier : The emergence of the Romance languages and nations (The West; Vol. 4). Pro Quest, Ann Arbor, Me. 1984 (unchanged reprint of the Frankfurt / M. 1941 edition)

- Günter Holtus , Michael Metzeltin , Christian Schmitt (Hrsg.): Lexicon of Romance Linguistics . 12 volumes. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1988-2005, ISBN 3-484-50250-9 .

- Rebecca Posner: The Romance Languages. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1996, ISBN 0-521-23654-1 (EA New York 1966)

- Lorenzo Renzi: Nuova introduzione alla Filologia romanza (Studi linguistici e semio logici; Vol. 6). Il Mulino, Bologna 2002, ISBN 88-15-04340-3 (EA Bologna 1994).

- German: Introduction to Romance Linguistics. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-094516-4 (EA Tübingen 1981).

-

Carlo Tagliavini : Le origini delle lingue neolatine. Introduzione alla filologia romanza . Editorial Patron, Bologna 1982, ISBN 88-555-0465-7 .

- German: Introduction to Romance Philology. Francke, Bern 1998, ISBN 3-8252-8137-X (EA Bern 1972).

Short introductions

- Alwin Kuhn: The Romance Philology, Vol. 1: The Romance Languages. Francke, Bern 1951.

- Petrea Lindenbauer, Michael Metzeltin , Margit Thir: The Romance languages. An introductory overview. Egert, Wilhelmsfeld 1995, ISBN 3-926972-47-5 .

- Michael Metzeltin: Las lenguas románicas estándar. Historia de su formación y de su uso. Academia de la Llingua Asturiana, Uviéu 2004, ISBN 84-8168-356-6 ( Google books ).

- Michael Metzeltin: Explanatory grammar of the Romance languages, sentence construction and sentence interpretation (Praesens study books ; Vol. 17). Praesens, Vienna 2010, ISBN 978-3-7069-0548-0 .

- Rainer Schlösser: The Romance Languages (Beck'sche series; Vol. 2167). Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-44767-8 (EA Munich 2001).

- Carl Vossen: Mother Latin and her daughters. Europe's language and its future . Stern-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1999, ISBN 3-87784-036-1 (EA Frankfurt / M. 1968).

Web links

- Michael Metzeltin: Las lenguas románicas estándar. Historia de su formación y de su uso . Oviedo, 2004

- Elisabeth Burr: Classification of Romance Languages. University of Leipzig

- Jacques François: The separation of the Romance-speaking area. Université de Caen & LATTICE (UMR 8094, Paris 3 - ENS), lecture at the Institute for Romance Studies at the University of Stuttgart, June 10, 2015

Individual evidence

- ↑ Reinhard Kiesler: Introduction to the problem of vulgar Latin. Volume 48 of Romanistic workbooks, Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 2006, ISBN 3-484-54048-6 , p. 2.

- ^ Saint Ignatius High School, Cleveland, USA ( Memento of September 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive ): comparative compilation of various sources on the spread of world languages (English) .

- ↑ Harald Haarmann : World history of languages. From the early days of man to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-69461-5 , pp. 134-135.

- ^ Andrés de Poza: De la antigua lengua, poblaciones, y comarcas de las Españas. 1587.

- ↑ Gerhard Jäger : How bioinformatics helps to reconstruct the history of language. In: Alfred Nordheim , Klaus Antoni (Ed.): Crossing the Genz. Man in the field of tension between biology, culture and technology. transcript, Bielefeld 2013, ISBN 978-3-8376-2260-7 , p. 140

- ↑ Wolfgang Dahmen: The Romance Languages in Europe. In: Uwe Hinrichs (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Eurolinguistik (= Slavic study books vol. 20). Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 3-447-05928-1 , p. 209 f.

- ↑ Martin Haase: The Spanish from a typological and historical-comparative point of view. Bamberg, pp. 1-16 .

- ↑ Ethnologue Information on the Romanian language.

- ↑ See Joachim Grzega : Romania Gallica Cisalpina: Etymological-geolinguistic studies on the Northern Italian-Rhaeto-Romanic Celticisms . (= Supplements to the journal for Romance philology. 311). Niemeyer, Tübingen 2001.

- ^ Glottolog 3.2 - Dalmatian Romance. Accessed July 8, 2018 .

- ↑ See Amos Cardia: S'italianu in Sardìnnia candu, cumenti e poita d'ant impostu: 1720–1848. Poderi e lìngua in Sardìnnia in edadi Spanniola. Iskra, Ghilarza 2006, ISBN 88-901367-5-8 .