Angola

| Portuguese Republic of Angola | |||||

| Republic of Angola | |||||

|

|||||

|

Motto : Virtus Unita Fortior ( Latin " Fortitude united is stronger") |

|||||

| official language | Portuguese , official national languages (língua nacional) alongside Umbundu , Kimbundu , Kikongo , TuChokwe , Ngangela , Oshivambo | ||||

| capital city | Luanda | ||||

| form of government and government | presidential republic | ||||

| Head of state , at the same time head of government |

President Joao Lourenco |

||||

| surface | 1,246,700 km² | ||||

| population | 31.13 million (2020 estimate) | ||||

| population density | 25 inhabitants per km² | ||||

| population development | + 3.2% (estimate for 2019) | ||||

gross domestic product

|

2019 (estimate) | ||||

| Human Development Index | 0.581 ( 148th ) (2019) | ||||

| currency |

Kwanza (AOA) Namibian Dollar (NAD) (only in Santa Clara ) |

||||

| independence | 11 November 1975 (from Portugal ) |

||||

| national anthem | Angola Avant | ||||

| national holiday | November 11 (Independence Day) | ||||

| time zone | UTC+1 (WAT) | ||||

| License Plate | ANG | ||||

| ISO 3166 | AO , AGO, 024 | ||||

| Internet TLD | .ao | ||||

| telephone area code | +244 | ||||

Angola ( German [ aŋˈgoːla ], Portuguese [ ɐŋˈgɔlɐ ]; called "Ngola" in Kimbundu , Umbundu and Kikongo ) is a country in south-western Africa . National Day is November 11, the anniversary of independence in 1975. Angola borders Namibia , Zambia , the Republic of the Congo , the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Atlantic Ocean - the Angolan exclave of Cabinda lies to the north between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo on the Atlantic Ocean .

The name Angola derives from the title Ngola of the kings of Ndongo , a vassal state of the historic Congo Empire located east of Luanda . The region around Luanda was given this name in the 16th century by the first Portuguese sailors who landed on the local coast and erected a padrão , a stone cross as a sign of possession for the Portuguese king. The term was extended to the region around Benguela at the end of the 17th century , and then in the 19th century to the territory, which was not yet defined at that time, and which Portugal planned to occupy colonially .

geography

Geographical location

The Republic of Angola is located between 4° 22′ and 18° 02′ south latitude and 11° 41′ and 24° 05′ east longitude. The country is roughly divided into a narrow lowland along the Atlantic coast that rises towards the east, inland, towards the Bié highlands : it makes up most of Angola, is flat in the south and mountainous in the middle of the country. The highest mountain is Môco , located in this highland, at 2619 m above sea level. The Zambezi flows through eastern Angola .

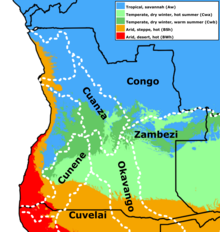

climate

Angola is divided into three climate zones:

It is tropical on the coast and in the north of the country, which means that there are high daytime temperatures between 25 and 30 °C all year round, and it is only slightly cooler at night. From November to April is the rainy season. The climate is heavily influenced by the cool Benguela Current (17–26 °C), so fog is common. The average rainfall is 500 mm, in the south hardly 100 mm annually.

The highlands in the center and south of the country are temperate-tropical, with significant temperature differences between day and night, especially in winter. In Huambo , for example, the temperatures in July are between 25 °C during the day and 7-8 °C at night, and there is also an extreme drought. Similar to the coast, the rainy season is from October to April. On average, around 1000 mm of rain falls per year.

In the southeast of the country it is mostly hot and dry with cool nights in winter and heat and occasional rain in summer. Annual precipitation varies around 250 mm.

hydrology

The " water tower " of the country is formed by the Bié highlands. From there, Angola is divided into 5 main catchment areas. The two largest are those of the Congo and the Zambezi. Together they drain over 40% of the country's surface. The areas that flow over the Okavango are around 12%. This means that a good half of the country drains out of the country via very large catchment areas. In addition, there is the Cuanza , also with about 12%, and the Cunene with almost 8%. Also worth mentioning is the Cuvelai-Etosha catchment area, which drains to the south. The remaining almost 20% of the country are coastal rivers . The water resources in southern Angola are of great importance for the neighboring countries Botswana and Namibia. Hence, together, in 1994, they formed the Permanent Okavango River Basin Water Commission .

Flora and fauna

Depending on the climate, the vegetation ranges from tropical rainforest in the north and in Cabinda to tree savannas in the center to dry grass savannas interspersed with euphorbia (spurge family), acacia and baobab trees . Starting from Namibia, a strip of desert stretches along the south-west coast. The fauna of Angola is rich in wild animals, there are elephants , hippos , cheetahs , wildebeests , crocodiles , ostriches , rhinos and zebras . The expansion of agriculture, but also the destruction caused by civil wars and the ivory trade are endangering the survival of many species.

In Angola there are 13 protected areas (national parks and nature reserves) with a total area of 162,642 km², representing 12.6% of the national territory.

story

The first inhabitants of present-day Angola were Khoisan , who were largely displaced by Bantu ethnic groups from the 13th century onwards. In 1483 Portuguese trading posts began to be established on the coast, especially in Luanda and its hinterland, and a century later also in Benguela . The systematic conquest and occupation of today's territory did not begin until the beginning of the 19th century and was not completed until the mid-1920s.

From the mid-1920s to the early 1960s, Angola was subject to a "classical" colonial system. The colonial power Portugal was ruled by a military dictatorship from 1926 until the Carnation Revolution in 1974 ( Carmona until 1932 , Salazar until 1968 , Caetano until 1974 ).

Until the end of the colonial period, Angola's most important economic basis was agriculture and animal husbandry, which took place both on the large farms of European settlers and on the family farms of Africans. Diamond mining was central to the colonial state. Another important component was trade. Modest industrialization and development of the service sector only occurred in the late colonial phase, i.e. in the 1960s and 1970s. Oil deposits were found on the mainland in the 1950s and in the sea off Cabinda in the 1960s, but production on a larger scale only began at the very end of the colonial period.

In the 1950s, nationalist resistance began to form, which culminated in an armed struggle for liberation in 1961 (1960 – the “ Africa Year ” – 18 colonies in Africa (14 French , two British , one Belgian and one Italian ) had independence from their own acquired by colonial powers ; see also Decolonization of Africa ).

From 1962, Portugal therefore carried out drastic reforms and initiated a late colonial phase that created a new situation in Angola, but did not bring the war of independence to a standstill. The War of Independence came to an abrupt end when on April 25, 1974 a military coup in Portugal triggered the Carnation Revolution , brought down the dictatorship there and the new democratic regime immediately began decolonization.

The coup in Portugal triggered armed clashes in Angola between the liberation movements FNLA , MPLA and UNITA , whose ethnic roots varied in the country. The USA, Zaire (“ Democratic Republic of the Congo ” since 1997 ) and South Africa (still under the apartheid regime) intervened in these disputes on the side of the FNLA and UNITA, the Soviet Union and Cuba on the side of the MPLA. The latter prevailed and proclaimed independence in Luanda in 1975, at the same time as FNLA and UNITA in Huambo .

The “counter-government” of FNLA and UNITA quickly disintegrated, but immediately after the declaration of independence a civil war broke out between the three movements, from which the FNLA quickly withdrew while UNITA led it until the death of its leader Jonas Savimbi in continued in 2002. At the same time, the MPLA established a political-economic regime modeled after that of the then socialist countries. Cuba's civil development assistance during this period was notable.

This regime was abandoned in 1990/91 during a hiatus in the civil war in favor of a multi-party system. Elections were held in September 1992 , in which UNITA also took part. The MPLA received 53.74 percent of the vote and 129 of the 220 seats in Parliament. The MPLA's presidential candidate, José Eduardo dos Santos , received 49.56 percent of the vote; according to the constitution, a run-off election (against Jonas Savimbi) would have been necessary.

This resulted in a bizarre situation that lasted until 2002. On the one hand, representatives of UNITA and FNLA took part in parliament and even the government, on the other hand, UNITA's military arm continued to fight after the election. The political system developed into an authoritarian presidential democracy, while in the country destruction z. T. of considerable magnitude.

On February 22, 2002, the army discovered Jonas Savimbi in the east of the country and shot him dead. After that, UNITA stopped the fight immediately. It dissolved its military arm, part of which was incorporated into the Angolan Army. Under a new leader, Isaias Samakuva, it assumed the role of a normal opposition party. In the September 2008 general election, the MPLA received 81.64% of the vote (UNITA 10.39%, FNLA 1.11%).

In 2002 the reconstruction of the destroyed towns, villages and infrastructure began. Thanks to oil production and the temporarily high oil price , there was enough foreign currency for this . The governing group around the president also used this to greatly enrich themselves, an example of the ruling kleptocracy .

A new constitution passed in January 2010 has strengthened the position of the MPLA and especially the state president. The type of government doctrine is an authoritarian presidential system. João Lourenço has been president since 2017 and seems to be partially cleaning up the corruption of his predecessor, although he is still the leader of the ruling party and Lourenço is his deputy. In December 2019, the assets of Isabel dos Santos , the old president's daughter, were frozen and confiscated, estimated at $2.2 billion .

population

| year | resident |

|---|---|

| 1940 | 3,738,010 |

| 1950 | 4,145,266 |

| 1960 | 4,840,719 |

| 1970 | 5,620,001 |

| 2014 | 25.789.024 |

In Angola there have only been two censuses in 1970 and 2014. In 2020 the national statistical office published a projection. Accordingly, the population was 31.13 million. Angola's population is one of the fastest growing in the world. In 2019, the population growth was 3.2% and the fertility per woman was 5.4 children. In the 1970s, the figure was even around 7.5 children per woman. The median age of the population in 2020 was an estimated 16.7 years. 46.6% of the population is younger than 15 years. For the year 2050, according to the UN's average population forecast, a population of over 77 million is expected.

An acute demographic problem, with unforeseeable economic, social and political consequences, has arisen in Angola from the state of war that has lasted for four decades. Around 2000, a significant part of the rural population had fled to the cities, to impassable areas (mountains, forests, marshlands) or to neighboring countries (Namibia, Botswana, Zambia, DR Congo, Republic of Congo). Contrary to all expectations, there was no massive backflow after the peace agreement. A part of the population has returned to their places of origin, but – as the surveys of the last few years show – on balance the inland population has even continued to decrease. This is not least due to the fact that the economy – with the exception of agriculture and diamond mining – is predominantly concentrated on the coastal strip. However, the 2014 census revealed that despite generally poor living conditions, the decline in the rural population was less drastic than feared: it accounts for just over 60% of the total population.

ethnic groups

Most Angolans are Bantu and belong to three ethnic groups: more than a third are Ovimbundu , based in the Central Highlands, the adjacent coastal strip and now also having a strong presence in all major cities outside this area as well; a scant quarter are Ambundu (language: Kimbundu ), which predominate in a wide stretch of land from Luanda to Malanje; Finally, 10 to 15% belong to the Bakongo , a people settled in western Congo-Brazzaville and the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in north-western Angola, which now also represents a strong minority in Luanda.

Numerically smaller ethnic groups are the Ganguela , actually a conglomeration of smaller groups from eastern Angola, then the Nyaneka-Nkhumbi in the southwest who are mostly pastoral farmers, the Ovambo (Ambo) and Herero of southern Angola (with relatives in Namibia), and the Tshokwe (including the Lunda ) . northeastern Angola (and southern DRC and northwestern Zambia), which have migrated southward in small groups over the last century. Some small groups in the far southwest are referred to as Xindonga . Finally, there are residual Khoisan ( San ) groups scattered throughout southern Angola that do not belong to the Bantu.

About 2% of the population are mestiços , i.e. mixed races of Africans and Europeans. With 320,000 to 350,000 people at the end of the colonial period, the Portuguese were the largest ethnic group of European origin in the country. More than half of them were born in the country, often in the second or third generation, and felt closer to Angola than to Portugal. The others had immigrated in the late colonial period or been posted there as employees/officials of state institutions (including the military). Most Portuguese fled to Portugal, Brazil or South Africa shortly before or after Angola's declaration of independence in late 1975, but their numbers have now increased to around 170,000, with a possible 100,000 other Europeans, Latinos and North Americans. The Europeans are now joined by a large group of Chinese, estimated at around 300,000 people, who came and are coming to Africa as part of a wave of immigration. In 2017, 2.1% of the population was foreign-born.

Up until 1974/75, around 130 German families ( Angola-Germans ) lived in the country as farmers or entrepreneurs, especially in the regions around Huambo and Benguela ; at that time there was even a German school in the city of Benguela. Almost all have since left the country.

In contrast to other (African and non-African) countries, the ethnic differences in Angola have only caused social dynamism to a certain extent. When Bakongo, who had fled to Congo-Kinshasa in the 1970s, settled in Luanda in large numbers upon their return, this led to mutual "alienation" between them and the local Ambundu, but not to massive or even violent ones conflicts. When Ambundu and Ovimbundu faced each other in the civil war, the conflict also took on ethnic overtones at its peak; since peace has prevailed, these have subsided significantly. In conflicts of all kinds, however, such demarcations can come into play again. Furthermore, the problem of racial relations between blacks, mixed races and whites is far from settled, since it is politically manipulated and, in turn, causes politics.

languages

Almost all of the languages spoken in Angola belong to the Bantu language family . Portuguese is the official language in Angola. It is spoken at home by 85% of the urban population and 49% of the rural population. All things considered, of all African countries, Angola has probably adopted the language of the former colonial power the most. Among Angola's African languages, the most widespread are Umbundu , spoken by 23% of the population, particularly of the Ovimbundu ethnic group , Kikongo (8.24%) of the Bakongo , and Kimbundu (7.82%) of the Ambundu and the Chokwe (6.54%) of the Chokwe . Other languages include Ngangela , Oshivambo ( Kwanyama , Ndonga ), Mwila , Nkhumbi , Otjiherero , and Lingala , introduced by migrants from Zaire in the 20th century . A total of around 40 different languages/dialects are spoken in Angola (depending on classification criteria).

religions

There are almost 1,000 religious communities in Angola. According to the 2014 census, 38.1% of the population belong to the Protestant churches , which were often founded during the colonial period , while 41.1% of the population are followers of the Roman Catholic Church . 12.3% of the inhabitants do not belong to any religious community.

Methodists are particularly present in the area from Luanda to Malanje, Baptists in the north-west and Luanda. In central Angola and the adjacent coastal towns, the Igreja Evangélica Congregacional em Angola (Evangelical Congregational Church in Angola) is primarily represented. Various smaller communities also come from the colonial period, such as Lutherans (e.g. in southern Angola) and Reformed (especially in Luanda). In addition, there are Adventists , New Apostolic Christians and (not least due to influences from Brazil) a variety of Pentecostal-Charismatic free churches and Jehovah's Witnesses since independence . The new communities, such as the Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus (IURD, United Church of the Kingdom of God) organized as a business enterprise, which originated in Brazil and from there spread to the other Portuguese-speaking countries, are particularly prominent in the larger ones represented in cities and in some cases have a considerable influx.

Due to influences from South Africa and Namibia, a small offshoot of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa formed in the 2000s . Finally, there are two Christian syncretist communities, the Kimbangists , rooted in DR Congo, and the Tokoists , which arose in colonial Angola .

Only a vanishingly small part of the population adheres exclusively to traditional religions , but among Christians it is not uncommon to find fragments of ideas that come from these religions.

According to the 2014 census, the proportion of Muslims (almost all Sunni ) is only 0.4 percent. It is made up of immigrants from different, mostly African, countries who, because of their diversity, do not form a community. Saudi Arabia tried to spread Islam in Angola. In 2010, for example, it announced that it would finance the establishment of an Islamic university in Luanda. In November 2013, however, Islam and numerous other organizations were denied recognition as a religious community because they were not compatible with Christianity. In addition, buildings erected without planning permission were slated for demolition. More than 60 mosques in the country have been closed.

The Catholic Church, the traditional Protestant churches and some free churches maintain social institutions designed to compensate for deficiencies in social or state provision. The Catholic Church and the traditional Protestant Churches occasionally speak out on political issues, and they are heard differently.

social

health care

From a European perspective, the food and health situation of the Angolan population is largely catastrophic. Only around 30% of the population have access to basic medical care and only 40% have access to sufficiently pure drinking water . Every year, thousands of people die from diarrheal diseases or respiratory infections. In addition, malaria , meningitis , tuberculosis and diseases caused by worms are common. According to UNAIDS estimates, the HIV infection rate is 2%, which is very low for the region. The reason for this is the isolation of the country during the civil war.

In 1987, a first major cholera outbreak was reported in Angola, involving 16,222 cases and 1,460 deaths. It started on April 8, 1987 in the province of Zaire and spread to many other areas including the province of Luanda. After falling between July and October, the number of cases increased from November and was considered endemic , with outbreaks continuing in 1988 in many provinces. In 1988, two-thirds of cholera cases in Africa were reported from Angola (15,500 cases versus 23,223 for all of Africa). No more cholera cases were reported between 1997 and 2005.

Outbreak of cholera 2006/2007:

Between February 13, 2006 and May 9, 2007, Angola experienced one of its worst cholera outbreaks in history, reporting 82,204 cases with 3,092 associated deaths and a total case fatality rate (FVA) of 3.75%. The peak of the outbreak was reached in late April 2006 with a daily incidence of 950 cases.

The outbreak started in Luanda and quickly spread to 16 of the 18 provinces. The development suggests that the disease could have spread both by sea and by land. Angola's cholera outbreaks are reportedly mainly due to poor access to basic services such as clean water and sanitation. While acknowledging the success of all relief efforts in containing the cholera outbreak, the lack of a long-term and sustainable supply of clean water and sanitation, as well as improved health care, still leaves many people vulnerable to cholera and other related diseases such as Marburg , Polio etc. Although Luanda reported the most cases (around 50%), other provinces such as Bié, Huambo, Cuanza Sul and Lunda Norte had the highest FVA value. This can be explained by the difficult access to health facilities, with the provinces far from Luanda being particularly underserved.

In 2007 Angola reported 18,422 cases including 513 deaths (FVA 2.78%). Luanda recorded 37% of all cases and Benguela 22.5%. Cuanza Sul reported the highest case fatality rate at 12%.

About a third of the population is partially or totally dependent on foreign food aid . In 2015, 14.0% of the population was malnourished. In 2000, it was still 50.0% of the population.

The under-five mortality rate is the second highest in the world, statistically one child dies every three minutes in Angola. Due to the lack of medical care, the number of women who die during childbirth is also extremely high. The average life expectancy at birth is given as 61.2 years. Leprosy in Angola remains a major concern for public health officials in the country. In 2010, a total of 1048 cases of this chronic infectious disease were identified.

| Period | life expectancy in years |

Period | life expectancy in years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950-1955 | 35.9 | 1985-1990 | 45.3 |

| 1955-1960 | 1990-1995 | ||

| 1960-1965 | 1995-2000 | 45.7 | |

| 1965-1970 | 40.0 | 2000-2005 | 48.1 |

| 1970-1975 | 2005-2010 | 52.7 | |

| 1975-1980 | 2010-2015 | 57.7 | |

| 1980-1985 | 2015-2020 | 60.5 |

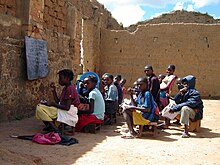

education

During the colonial period, education was neglected until the last decade and was always an instrument of colonial politics. After independence, a systematic new beginning began, in which cooperation with Cuba played an important role. The civil war hampered these efforts and led to a blatant shortage of teachers, especially in rural areas. Overall, however, the development of a new educational system continued, especially in the cities, where gradually half the population was concentrated. Since the peace of 2002, great efforts have been and are being made to improve the situation and eliminate the enormous deficits. At the same time, school reform began in Angola with the intention of making school content more relevant to children and achieving better outcomes.

In Angola, less than two-thirds of school-age children attend school. In primary schools , 54% of children repeat one or more classes. By the time children reach fifth grade, only 6% of children in their age group are still in school. This also has to do with the fact that a valid identity card has to be presented for promotion to higher classes, which many do not have. This high dropout rate corresponds to the lack of fifth and sixth grade schools. The literacy rate of the adult population was 71.1% in 2015 (women: 60.2%, men: 82.0%)

Of the population >18 years, 47.9% have no school leaving certificate, 19.9% have a primary school leaving certificate, 17.1% have an intermediate school leaving certificate (I ciclo do ensino secundário), 13.2% have a secondary school leaving certificate (II ciclo do ensino secundário) and 2.0% have a university degree. For 18-24 year olds, the rates are 25% (no school leaving certificate), 34% (primary school leaving certificate), 29% (intermediate school leaving certificate), 13% (secondary school leaving certificate) and 0% (university degree). The percentage of the population >24 with a university degree varies greatly from province to province. Luanda (5.4%) and Cabinda (3.8%) have the highest proportions, Cunene (0.6%) and Bié (0.5%) the lowest.

In cooperation with the Angolan Ministry of Education, the aid organization Ajuda de desenvolvimento de Povo para Povo em Angola runs seven teacher training centers in Huambo , Caxito , Cabinda , Benguela , Luanda , Zaire and Bié , the so-called Escolas dos Professores do Futuro , where by the end of 2006 more when 1000 teachers were trained to work in rural areas. By 2015, eight more of these teacher training centers are to be set up and 8,000 teachers trained.

Until the late 1990s, higher education consisted of the state-run Universidade Agostinho Neto , whose 40 or so faculties were spread across the country and were in poor condition overall. In addition, there was only the Universidade Católica de Angola (UCAN) in Luanda.

There is now a growing number of private universities, especially in Luanda. These include the Universidade Lusíada de Angola, the Universidade Lusófona de Angola, and the Universidade Jean Piaget de Angola, all of which are closely linked to the universities of the same name in Portugal. The Angola Business School was also created with the support of a Lisbon university.

Purely Angolan initiatives are the Universidade Privada de Angola, the Universidade Metodista de Angola, the Universidade Metropolitana de Angola, the Universidade Independente de Angola, the Universidade Técnica de Angola, the Universidade Gregório Semedo, the Universidade Óscar Ribas, the Universidade de Belas, and the Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Relações Internacionais.

All of these universities are based in Luanda, although some also have branches in other cities, known as pólos, such as the Universidade Privada de Angola in Lubango , the Universidade Lusófona de Angola in Huambo and the Universidade Jean Piaget in Benguela . In terms of decentralization of higher education, however, it was crucial that in 2008/2009 six regional universities, each with its own name, were spun off from the Universidade Agostinho Neto, which took over the existing faculties and usually founded others, and which within their respective areas of responsibility in other cities "pólos set up. In Benguela the Universidade Katyavala Bwila was created, in Cabinda the Universidade 11 de Novembro, in Huambo the Universidade José Eduardo dos Santos with "pólo" in Bié , in Lubango the Universidade Mandume ya Ndemufayo (see also Mandume yaNdemufayo ) with "pólo" in Ondjiva , in Malanje with Saurimo and Luena the Universidade Lueij A'Nkonde and in Uíge the Universidade Kimpa Vita.

In most cases, the namesakes were African leaders from the pre-colonial period or from the period of primary resistance to colonial conquest. All universities are struggling with set-up difficulties. The jurisdiction of the Universidade Agostinho Neto was limited to the provinces of Luanda and Bengo. However, this development has so far only partially overcome the qualitative inadequacies of higher education. In Luanda, due to the diversity of universities, some of them are struggling with declining demand.

See also: List of universities in Angola

politics

| Index name | index value | World Rank | interpretation aid | year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fragile States Index | 87.3 out of 120 | 34 of 178 | Country stability: major warning 0 = very sustainable / 120 = very alarming |

2020 |

| democracy index | 3.66 out of 10 | 117 of 167 | Authoritarian regime 0 = authoritarian regime / 10 = full democracy |

2020 |

| Freedom in the World | 31 out of 100 | --- | Freedom status: not free 0 = not free / 100 = free |

2020 |

| Press Freedom Index | 34.06 out of 100 | 103 of 180 | Recognizable problems for press freedom 0 = good situation / 100 = very serious situation |

2021 |

| Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) | 27 out of 100 | 142 of 180 | 0 = very corrupt / 100 = very clean | 2020 |

Political system

Currently, political power is concentrated in the presidency. Until 2017, the executive consisted of the long-serving president, José Eduardo dos Santos , who was also commander-in-chief of the armed forces and head of government, and the Council of Ministers. The Council of Ministers, consisting of all government ministers and deputy ministers, meets regularly to discuss political issues. The governors of the 18 provinces are appointed by the president and act according to his ideas. The 1992 Constitutional Law establishes the essential features of the structure of government and sets out the rights and duties of citizens. The legal system, based on Portuguese law and common law, is weak and fragmented. Courts operate in only twelve out of more than 140 municipalities. The Supreme Court serves as the court of appeal. A constitutional court - capable of impartial assessment - was not appointed as of 2010, although the law provides for it. João Lourenço has been president since 2017 and seems to be partially cleaning up the corruption of his predecessor, although he is still the leader of the ruling party and Lourenço is his deputy. In December 2019, the assets of Isabel dos Santos , the old President's daughter, were frozen, estimated at $2.2 billion .

The constitution adopted by parliament in 2010 further intensified the authoritarian traits of the political system. It should be noted that presidential elections have been abolished and that in future the leader and vice-president of the party that receives the most votes in parliamentary elections will automatically become president and vice-president respectively. The President uses various mechanisms to control all state organs, including the constitutional court that has now been created; consequently one cannot speak of a separation of powers. So it is no longer a presidential system, as there is in the USA or France, but a system that constitutionally falls into the same category as Napoleon Bonaparte 's Caesarist monarchy , the corporate system of António de Oliveira Salazar according to the Portuguese constitution of 1933, the Brazilian military government under the 1967/1969 constitution and various authoritarian regimes in contemporary Africa.

The 27-year civil war in Angola has severely damaged the country's political and social institutions. The UN estimates that there were 1.8 million refugees in Angola. Several million people were directly affected by acts of war. Every day, living conditions across the country, especially in Luanda ( the capital has grown to over five million inhabitants as a result of immense rural exodus), reflected the collapse of administrative infrastructure and many social institutions. Hospitals often had no medicines or basic supplies, schools had no books, and government employees had no equipment to go about their daily work. Since the end of the civil war in 2002, massive efforts have been made to rebuild, but traces of it can be found all over the country. The diverse problems and possibilities of reconstruction are described in great detail by Angola-Portuguese José Manuel Zenha Rela.

The two most influential unions are:

- UNTA (União Nacional dos Trabalhadores Angolanos); National Union of Angolan Workers

- CGSILA (Confederação Geral dos Sindicatos Independentes e Livres de Angola); General Confederation of Free and Independent Trade Unions of Angola

houses of Parliament

On September 5 and 6, 2008, Angolans elected a new national assembly for the first time since the end of the civil war . According to SADC and African Union (AU) election observers, the election was “generally free and fair”. EU observers pointed to the very good technical and logistical preparation of the elections, the high turnout and the peaceful voting process. However, the chaotic holding of the elections, especially in the capital Luanda, was criticized. According to international observers, there were no free conditions for fair elections that were equal for all parties in the period leading up to the elections. Almost all observers unanimously emphasized that the state media institutions were massively abused in favor of the MPLA, and that the opposition parties outside of Luanda did not have free access to the electronic media. Angolan civil society speaks of state-financed election gifts from the MPLA and intimidation by its sympathizers.

The MPLA won the election with just under 82% of the votes cast, while UNITA garnered just over 10% of the votes. The main opposition party initially lodged a complaint against the election, but after it was rejected it conceded defeat.

The following parties had seats in parliament after this election:

- Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola (FNLA) – (“National Front for the Liberation of Angola”, former liberation movement, opposition) 3 seats

- Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA) – (“People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola”, former liberation movement, in power since independence) 191 seats

- Partido de Renovação Social (PRS) – (“Party of Social Renewal”, electorate concentrated in the Lunda and Chokwe ethnic groups , opposition), 8 seats

- União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (UNITA) – (“National Union for the Total Independence of Angola”, former liberation movement, opposition) 16 seats

- Nova Democracia – União Eleitoral (ND) (“New Democracy Electoral Alliance”, opposition) 2 seats

In 2011-2012 the regime confirmed its intention to hold parliamentary elections again in 2012, respecting for the first time the constitutional requirement that elections be held every four years. In addition to the parties represented in Parliament, 67 other parties were eligible to stand in these elections. José Eduardo dos Santos has repeatedly announced his intention not to stand again in these elections, raising the question of who would be his successor as President.

The elections then took place on August 31, 2012. Contrary to his previous declarations, José Eduardo dos Santos was once again the MPLA's lead candidate, which received just over 70% of the votes - less than in 2008, but still a very comfortable majority that guaranteed dos Santos' retention in office. UNITA received around 18% and the newly founded CASA (Convergência Ampla de Salvação de Angola) around 6%. Other parties did not enter Parliament, as none received even 2% of the vote. It is worth noting the strong differences between the regions, especially with regard to the results of the opposition: it received around 40% in the provinces of Luanda and Cabinda, where the level of politicization is particularly high.

Elections were held again on August 23, 2017. President dos Santos did not stand again. The MPLA received around 65% of the votes and thus continued to provide the president. UNITA came to around 27%.

human rights

According to Amnesty International, in 2008 there were repeated arbitrary arrests of people who had exercised their right to freedom of expression, assembly and association. There is no state social security system. Single women face additional difficulties, especially in rural areas. In some communities, women have traditionally been forbidden from owning and cultivating their own land.

After the 2017 National Assembly elections, freedom of expression, freedom of the press and assembly improved under the new President João Lourenço . State-run media reported more freely and independently, senior officials from the ruling MPLA party were replaced, and contracts with media outlets owned by members of the former president's family who acted as the party's mouthpiece were terminated. Even during the election campaign, the media reported on the opposition's election appearances and all parties were given airtime on state television. Freedom of assembly was also largely guaranteed. Since the new President took office, there have been no reports of convictions or arrests of journalists critical of the government.

Up until the 21st century, homosexuality in Angola was punishable by imprisonment or labor camps as an “offending against public morals” under Articles 71 and 72 of the penal code. Not only were these provisions abolished in 2018, but discrimination based on sexual orientation was banned. Employers who refuse to hire people because of their sexual orientation can be sentenced to up to two years in prison. Same-sex relationships have long been taboo in parts of society.

In an open letter, several human rights groups and figures in the country called on US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to address the state of democracy in Angola during her 2009 trip to Africa. “There is a global notion that Angola is making great democratic strides. In reality, people with different ideas (than those of the government) are persecuted and arrested. The right to rally does not exist,” lamented David Mendes of the organization Associação Mãos Livres (Association of Free Hands). China is gaining more and more influence in Angola. "And everyone knows that China doesn't respect human rights," Mendes said. As early as 2007, Amnesty International called in an open letter to the EU to address the difficult human rights situation in Angola and put it on its agenda.

Observers in the country assess the general living conditions in Angola as potentially violent. The historical course from the violent actions of the former Portuguese state power in the colonial war to state independence in 1975, a subsequent 30-year civil war and extremely insecure social conditions with armed local conflicts up to the present has large parts of the Angolan population in the arbitrary use of violence from all sides accustomed to in everyday life. In the course of the country's recent history, respect for individual human life has been impaired and it now corresponds to the everyday experience of many citizens that only the ends would justify the means.

Statements in the media supporting executions show that the “physical extinction” of suspected or actual criminals is welcomed by the population. There is only a weak orientation towards rule of law standards, such as the right to life. Populist formations of opinion, also spread by and in the authorities, use the population's perceived fear of crime to keep Angolan citizens away from the rule of law, to distance themselves from human rights or not to demand their civil rights in everyday life. Parallel to this development are regionally occurring incidents in which there are raids and murders among the civilian population, which are not followed by any investigation and no criminal consequences for the perpetrators. These everyday experiences stand in contradiction to the political proclamations of the Angolan government in favor of supposedly guaranteed rule of law norms in the country.

political protest

Apparently under the influence of popular uprisings in Arab countries, there were attempts on March 7, 2011 and again at a later date to organize a large-scale demonstration in Luanda against the political regime in Angola. These were attempts to articulate protest independently of the opposition parties. The MPLA staged a “preventive counter-demonstration” in Luanda on March 5, with what it said was a million supporters. During the months that followed, protests took place online and at rap venues. On September 3, 2011, permission was again granted for a demonstration critical of the regime, primarily directed against the President of the Republic, which was then violently broken up using batons and firearms when it began to exceed the area allowed for it. About 50 people were arrested and awaiting summary conviction.

foreign policy

Angola has been a member of the United Nations since 1976 , a member of the WTO since 1996 and a member of OPEC since 2007 .

On October 15, 2013, Angola terminated its strategic partnership with Portugal . President dos Santos said relations between the two countries are not good. The reason for this was the fact that the Portuguese judiciary had charged some politically important Angolans, who belong to the immediate circle of the President, with crimes committed in Portugal (above all massive money laundering).

See also: List of Angolan ambassadors to the Holy See , List of Angolan ambassadors to Brazil , List of Angolan ambassadors to France , List of Angolan ambassadors to São Tomé and Príncipe

administrative division

territorial division

Angola is divided into 18 provinces (Portuguese: províncias , singular – província ):

| No. | province | capital city | population

2020 |

No. | province | capital city | population

2020 |

map | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | bengo | Caxito | 465,000 | 10 | Huíla | Lubango | 3,000,000 |

|

|

| 2 | Benguela | Benguela | 2,610,000 | 11 | Luanda | Luanda | 8,525,000 | ||

| 3 | Bee | Kuito | 1,765,000 | 12 | Lunda Norte | Lucapa | 1,030,000 | ||

| 4 | Cabinda | Cabinda | 850,000 | 13 | Lunda Sul | Saurimo | 650,000 | ||

| 5 | Cuando Cubango | menongue | 640,000 | 14 | malanje | malanje | 1,175,000 | ||

| 6 | Cuanza Norte | N'dalatando | 525,000 | 15 | Mexico | luena | 910,000 | ||

| 7 | Cuanza Sul | sum | 2,253,000 | 16 | Namibia | Moçâmedes | 610,000 | ||

| 8th | Cunene | Ondjiva | 1,195,000 | 17 | Uíge | Uíge | 1,760,000 | ||

| 9 | Huambo | Huambo | 2,470,000 | 18 | Zaire | M'banza Congo | 720,000 |

These 18 provinces are further subdivided into 162 municípios , 559 communes and 27,641 localities (localidades).

cities

There are no reliable figures for the population of the cities for the post-colonial period up to the 21st century. Qualitative progress was expected from the publication of the 2008 survey by the Instituto Nacional de Estatística , which became available after 2011. According to the 2020 projection, only the population figures of the Municípios, but not of the individual municipalities, were published in the official statistics. In addition to the largest city in the district, a municipality also includes a number of smaller towns in the area. Accordingly, the following picture emerges for the Municípios:

- Luanda as the capital has grown explosively. According to the 2014 census, the city has a population of 2.17 million, and 2.66 million according to the 2020 projection.

- The strongest percentage growth since the last census of 1970 has been in Cabinda (740,000 inhabitants) in the oil-rich province of the same name, as well as in the provincial capital Uíge (615,000 inhabitants).

- Of all the larger cities, Lubango has had the relatively least post-colonial shocks, but it has grown to around 930,000 inhabitants due to the influx not only from the immediate and wider surrounding area, but above all from the central highlands

- A very strong growth can be observed in the coastal cities of Benguela (660,000 inhabitants), Lobito (460,000 inhabitants) and Moçâmedes (360,000 inhabitants).

- After independence, Huambo initially became the second largest city in Angola, but was then largely destroyed and depopulated. Since 2002, its population has grown again to 875,000.

- Kuito was even more badly damaged than Huambo and had 545,000 inhabitants again in 2020.

military

The Armed Forces of Angola maintain an approximately 107,000-strong military , the Forças Armadas Angolanas (FAA). In 2020, Angola spent almost 1.7 percent of its economic output or USD 1.04 billion on its armed forces. Defense spending is among the highest in Africa. There are three branches of the armed forces: Army , Navy and Air Force and Air Defense Forces , of which the Army is the largest in terms of numbers. Military equipment comes mainly from the former Soviet Union . Small contingents are stationed in the Republic of the Congo and the Democratic Republic of the Congo . Chief of the General Staff is General Egídio de Sousa Santos .

business

General

With a gross domestic product of 95.8 billion US dollars (2016), Angola is the third largest economy in sub-Saharan Africa after South Africa and Nigeria. At the same time, a large part of the population lives in poverty.

Gross domestic product per capita in the same year was US$3,502 (US$6,844 adjusted for purchasing power). This put Angola in 120th place worldwide (out of a total of around 200 countries)

Angola's economy is suffering from the consequences of decades of civil war . However, thanks to its natural resources – primarily oil deposits and diamond mining – the country has experienced a major economic boom in recent years. Angola's economic growth in 2019 is the highest in Africa. However, the income from the raw material deposits does not reach the majority of the population, but rather corrupt beneficiaries within the political and economic rulers of the country and a slowly forming middle class. In 2015, only 4.4 million of the then 26 million inhabitants belonged to the middle class. A large proportion of citizens are unemployed and about half live below the poverty line, with drastic differences between urban and rural areas. A survey by the Instituto Nacional de Estatística in 2008 came to the conclusion that around 58% in the countryside were to be regarded as poor, but only 19% in the cities, a total of 37%.

In the cities, where more than 50% of the Angolans are now concentrated, the majority of the families depend on survival strategies. It is also there that social inequality is most tangible, especially in Luanda. Angola consistently ranks among the bottom of the UN Human Development Index .

National unemployment is 24.2%, with little difference between men and women. However, there are large differences between the provinces. While unemployment is highest in Lunda Sul (43%), Lunda Norte (39%), Luanda (33%) and Cabinda (31%), it is highest in Namibe and Huíla (17%), Malanje (16%), Cuanza Sul and Benguela (13%) lowest.

The main trading partners for the export of goods and raw materials are the USA, China , France , Belgium and Spain . Import partners are mainly Portugal , South Africa , USA, France and Brazil . In 2009, Angola became Portugal's largest export market outside of Europe, and around 24,000 Portuguese have moved to Angola in recent years, looking for employment or founding companies there. Much more important, however, is China's presence in the form of a whole range of large companies. After the end of the civil war in 2002, Angola asked China for a US$60 billion loan for infrastructure projects such as railways, roads, housing and hospitals. He is to be repaid with oil deliveries. However, the projects carried out by the Chinese companies - including Chinese workers - are of very poor quality. Newly built roads and railway lines have to be repaired every two years, the apartments show cracks and water infiltration after a few years, the city hospital Hospital Geral de Luanda , completed by the Chinese in 2006, had to be demolished six years after its inauguration and reopened in 2015.

The shadow economy, which developed during the "socialist" phase and grew exponentially during the phase of liberalization, is of fundamental importance for the population of Angola and which the government is currently trying to push back.

For a long time, Angola was dependent on its oil exports. Almost everything is imported, even bottled water, although the country has countless water sources. The fall in the price of oil put severe pressure on the national budget of the south-west African country. For several years it has been trying to diversify its economy - away from oil alone. This requires the expansion of the infrastructure, the modernization of the energy supply and better conditions for private investors.

In the Global Competitiveness Index , which measures a country's competitiveness, Angola ranks 137th out of 140 countries (as of 2018). Outside of oil production, domestic industry performance is very weak. The state exerts a great deal of influence on economic events. At the same time, corruption in the state sector is very pronounced. In the index for economic freedom , the country therefore only ranked 164th out of 180 countries in 2018.

fish factory

Elizabete Dias Dos Santos invested $25 million in her Solmar fish factory . The processing plant opened in autumn 2016. This type of assembly line production is unique in the sector in Angola. 120 people work in the factory. The suppliers also benefit, because more than 50,000 people live from traditional fishing in Angola. 40% of purchases are made from small fishermen. In order to attract private investors, the Angolan government had improved the conditions for domestic and foreign companies by, among other things, tax breaks, help with financing and simplified procedures for company formation.

steel mill

At Aceria de Angola , north of the capital Luanda , a steelworks with a capacity of 500,000 tons per year went into operation in 2015. 350 million dollars were invested. The plant has more than 500 jobs and offers many people an apprenticeship. The plant primarily recycles scrap and uses it to produce structural steel for concrete structures. The aim of the Lebanese-Senegalese operator Georges Fayez Choucair is to export. Therefore, the capacity of the plant is twice as high as the Angolan demand.

The plant also electrified the region and opened up the water supply. A high-voltage line had to be specially laid here. Unemployment in the region fell from around seventy to around twenty percent. Fayez Choucair is convinced: “You can't invest in a new country, in a completely new population and arrive and settle down like 'I'm rich' – no! Today you have to win over the population, this is not a project of an individual, but a community project!”

privatization program

At the end of 2018, the privatization authority IGAPE (Institito de Gestão de Activos e Participação do Estado) was founded with Presidential Decree Nº141/18, with which the government wants to completely or partially privatize 195 state-owned companies in order to strengthen the private sector and thus the growth of the country support financially. The program covers the main economic sectors such as the energy sector ( Sonangol ), telecommunications and IT, the financial sector (banking ( BAI ), insurance ( ENSA ), private equity funds), the transport sector ( TAAG ), tourism and the manufacturing sector including food processing and food processing Agriculture. Most of the companies are to be sold in 2020.

electricity supply

In 2011, Angola ranked 119th in the world in terms of annual generation with 5.512 billion kWh and 114th in terms of installed capacity with 1,657 MW. In 2014, the installed capacity was 1,848 MW, of which 888 MW in thermal power plants and 960 MW in hydroelectric power plants .

By 2014, only 30-40% of the population was connected to the electricity grid. Therefore, the government began planning significant investments ($23.4 billion by 2017) in the field of electricity supply. This includes the construction of new power plants, investments in transmission grids and rural electrification. A number of hydroelectric power stations are to be built on the Cuanza and Kunene to exploit the hydroelectric potential (estimated at 18,000 MW). The hydropower potential of the Kunene was already in the past a basis for projects and partial investments of extensive and never fully realized plans that arose within the framework of the former Cunene project between South Africa and Angola or Portugal. The Laúca dam with a planned capacity of 2,070 MW is currently being built. It is expected to go into operation in July 2017.

Currently (as of April 2015) there is no national grid in Angola , but there are three independent regional grids for the north, the center and the south of the country as well as other isolated island solutions. As a result, the surpluses from the northern grid cannot be fed into the other grids. By far the most important network is the northern one, which also includes the capital Luanda . After completion of the Laúca dam, the three power grids are also to be connected.

The electricity supply is unreliable across the country and is associated with regular blackouts that have to be compensated for by running expensive generators. The price per kWh is 3 AOA (approx. 2.5 € cents), but it is heavily subsidized and does not cover costs.

regional disparities

A structural problem of the Angolan economy is the extreme disparity between the various regions, which is partly due to the long-lasting civil war. Around a third of economic activity is concentrated in Luanda and the neighboring province of Bengo, which is increasingly becoming the capital's expansion area. On the other hand, there is stagnation or even regression in various inland regions. At least as serious as the social inequality are the clear economic differences between the regions. In 2007, Luanda concentrated 75.1% of all business transactions and 64.3% of jobs in (public or private) business enterprises. In 2010, 77% of all companies were located in Luanda, Benguela, Cabinda, Kwanza Sul Province and Namibe. In 2007, per capita GDP in Luanda and the neighboring province of Bengo had grown to around 8,000 US dollars, while in western central Angola it was just under 2,000 US dollars thanks to Benguela and Lobito, but in the rest of the country it was well under 1,000 US dollars. The trend towards economic concentration in the coastal strip, particularly in the "waterhead" Luanda/Bengo, has not diminished since the end of the civil war, but has continued and is causing a large part of the interior to be "emptied". So global growth figures hide the fact that Angola's economy is suffering from extreme imbalances.

corruption

One of the most prominent features of modern-day Angola is pervasive corruption . In Transparency International surveys , the country regularly ranks among the world's most corrupt, in a category with Somalia and Equatorial Guinea in Africa . In the first five years of the 21st century, it was estimated that corruption lost $4 billion in oil revenues, or 10% of GDP at the time.

The fight against corruption has been part of the government's program for years, but it is very seldom that this declaration of intent is actually implemented. A sensational exception at the end of 2010 was the dismissal of ten department heads and almost 100 officers from the immigration and border police SME (Serviço de Migrações e Estrangeiros), which is not only responsible for border control but also for issuing entry, residence and exit permits is.

The new President João Lourenço appears to be taking decisive action against corruption and nepotism. In his first year in office, he replaced several provincial governors, ministers, high officials and administrators of state-owned companies, such as the head of the state-owned oil company Sonangol , Isabel dos Santos , daughter of the previous president, or the chairman of the board of the state-owned oil fund with a value of 5 Billions US dollars, José Filomeno dos Santos , son of predecessor. José dos Santos was arrested in September 2018 and is suspected of illegally transferring US$500 million from the sovereign wealth fund abroad. He was released from custody in March 2019 and has since been at home awaiting his trial, which began in Luanda on December 9, 2019.

economic sectors

- Mining: Angola has rich offshore oil and diamond mines in the northeast of the country, as well as other mineral deposits in the country. The mineral resources make Angola one of the richest countries in Africa. Angola sells rough diamonds worth around one billion euros every year. From 2019, the gemstones will also be processed in the country itself in order to increase sales revenue. However, the bulk of the Angolan economy lives from oil and its products. In 2016, the country was Africa's second largest oil producer and exporter, after Nigeria, with production of 87.9 million tonnes (see Oil/Tables and Graphs ). According to OPEC, oil production accounts for around 95% of Angola's exports and 45% of its gross domestic product. The most important buyer of oil is the People's Republic of China , which has replaced the United States as the main trading partner. Angola was accepted as the 12th member of OPEC on January 1, 2007, but has only participated in the quota regime since March 2007. In 1975 additional uranium deposits were discovered on the border with Namibia . In April 2019, deposits of around 23 billion tons of mineral raw materials with economically interesting contents of rare earth metals were discovered in the province of Huambo , which are to be mined from 2020.

- Agriculture: About 85% of the working population is engaged in agriculture. The most important agricultural product for export is coffee , followed by sugar cane. Other important exports are corn and coconut oil. The production of potatoes, rice and cocoa is also worth mentioning. The breeding of cattle and goats is relatively widespread. Overall, agriculture is still suffering severely from the consequences of the civil war. Because of the danger from leftover landmines , many farmers refuse to cultivate their fields. Agricultural production is not sufficient to meet its own needs and the country is dependent on importing food. Agriculture is experiencing a slight upswing.

- Industry: The country's industry is poorly developed and suffered from the civil war. The main industry of Angola is the processing of agricultural products, primarily grain, meat, cotton, tobacco and sugar; along with the refining of petroleum. Important products continue to be fertilizers, cellulose, adhesives, glass and steel.

economic figures

The gross domestic product and Angola's foreign trade have grown massively in recent years due to rising income from oil exports. With the drop in the price of oil from 2014, there was a slump.

The important economic indicators gross domestic product, inflation, budget balance and foreign trade developed as follows:

| Change in gross domestic product (GDP), real | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in % compared to the previous year | ||||||||||||

| year | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| % change yoy | 18.3 | 20.7 | 22.6 | 13.8 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 5.2 | 6.8 | 4.8 | 3.0 | 0.0 |

| Source: World Bank | ||||||||||||

| Development of GDP (nominal) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| absolute (in billion US$) | per inhabitant (in thousand US$) | ||||||

| year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| GDP in billion US$ | 126.8 | 103.0 | 89.6 | GDP per capita (US$ thousand) | 4.7 | 3.6 | 3.1 |

| Source: World Bank | |||||||

| Development of the inflation rate | Development of the budget balance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in % compared to the previous year | in % of GDP ("minus" means deficit in the national budget) |

||||||||

| year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | year | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

| inflation rate | 8.8 | 7.3 | 10.3 | 34.7 | budget balance | −7.2 | −1.0 | ≈ 6.6 | ≈ 4.3 |

| Source: bfai | ≈ = estimated | ||||||||

| development of foreign trade | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in billion US$ and its change compared to the previous year in % | ||||||

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | ||||

| billion US$ | % yoy | billion US$ | % yoy | billion US$ | % yoy | |

| import | 26.8 | −6.8 | 28.8 | 7.5 | 16.8 | −41.7 |

| export | 67.7 | −4.4 | 58.7 | −13.4 | 33.0 | −43.7 |

| balance | 41.0 | 29.9 | 16.3 | |||

| Source: GTAI | ||||||

state budget

In 2016, the state budget included expenditure equivalent to US $33.50 billion , compared with income equivalent to US$27.27 billion. This results in a budget deficit of 6.5% of GDP .

Angola's debts totaled $31.4 billion as of December 2011. Almost half of that, around 17.8 billion, was foreign debt, according to Finance Minister Carlos Alberto Lopes. The main creditors of the Angolan government were China with 5.6 billion, Brazil with 1.8 billion, Portugal with 1.4 billion and Spain with 1.2 billion. The domestic debt of $13.6 billion results primarily from bonds and Treasury bills in support of ongoing government investment programs.

In 2006, government spending (as a percentage of GDP) accounted for the following areas:

In October 2019, a value -added tax (IVA) of 14% was introduced to make the national budget less dependent on oil exports. Previously there was only a consumption tax (IC) of 10%, which has been abolished. The calculated additional revenue for 2020 from the IVA is 432.4 billion Kwanzas, the calculated government revenue for 2020 excluding the petroleum sector is 712.3 billion Kwanzas.

The state budget for 2020 is 15.9 trillion kwanzas (27 billion euros). The government assumes an average crude oil price of 55 US dollars/barrel, an inflation rate of 24% and real economic growth of 1.8%. Social spending accounts for 40.7% of total spending. This also includes environmental protection, the expenditure for which has increased by 180% compared to the previous year.

foreign investments

Since the end of the civil war, private investments by Angolans abroad have increased steadily. This has to do with the fact that accumulation in the country is concentrated in a small social group, who are keen to diversify their possessions for reasons of security and maximizing profits. Preferred investment destination is Portugal, where Angolan investors (including the President's family) are present in banks and energy companies, in telecommunications and in the press, but also e.g. B. buy wineries and tourism objects.

traffic

rail transport

Rail transport in Angola is port-oriented. It operates on three networks that are not connected. Another route not connected to the three networks has since been discontinued. Both freight and passenger traffic take place. The total length of the route is 2,764 kilometers, of which 2,641 kilometers are in the Cape gauge customary in southern Africa and 123 kilometers in 600 millimeter gauge (as of 2010). Sole operator is the state company Caminhos de Ferro de Angola (CFA).

- long-distance bus transport

There are long-distance buses operated by Macon and Grupo SGO companies that connect Luanda with the country's main cities. Macon offers international connections to Windhoek and Kinshasa .

- air traffic

In Angola, 10 airlines are licensed for domestic flights: Aerojet, Air Guicango, Air Jet, Air 26, Bestfly, Heliang, Heli Malongo, SJL, Sonair and TAAG. With six aircraft, Sonair has the largest fleet for the domestic market. The airports with the most passengers in 2016 were: Luanda, Cabinda, Soyo, Catumbela and Lubango. TAAG is the international airline of Angola.

- maritime transport

There are passenger catamaran services from central Luanda to the suburbs of Benfica, Samba, Corimba, Cacuaco and Panguila, and a fast ferry service for passenger, vehicle and freight transport from Luanda to Cabinda, operated by the state-run Instituto Marítimo e Portuário de Angola . Further ship connections are planned to Lobito, Namibe and Porto Amboim.

telecommunications

There are 14 million mobile phone users in Angola, which is 46% of the population. The market is divided between the two companies Unitel (82%) and Movicel (18%). 20% of the inhabitants have access to the Internet, here too the two market leaders are Unitel (87%) and Movicel (12%). The fixed telephone network is only used by 0.6% of the population. This market is led by Angola Telecom (58%), followed by MsTelecom (21%), TV Cabo (19%) and Startel (2%). Only 7% of the population watch television, the market leader in this segment is the company ZAP (69%), followed by DStv (28%) and TV Cabo (3%).

On December 26, 2017, AngoSat-1 , the first Angolan communications satellite , was launched into geostationary orbit from Russia 's Baikonur rocket launch site . However, the planned orbital position could not be reached and it was abandoned a few months later.

On September 26, 2018, the South Atlantic Cable System , a 6165 km submarine cable connecting Angola to Brazil in 63 milliseconds, began operations. It also enables the Luanda – Miami connection (via Fortaleza ) in 128 milliseconds.

Culture

literature

Some well-known Angolan writers are Mário Pinto de Andrade , Luandino Vieira , Arlindo Barbeitos , Alda Lara , Agostinho Neto , Pepetela , Ondjaki and José Eduardo Agualusa .

Under the Arquivos dos Dembos / Ndembu Archives entry , 1160 manuscripts from Angola from the 17th to the early 20th centuries have been included in the UNESCO list of Memory of the World .

music

In music, Angola has a rich variety of regional styles. The music has had a great influence on Afro-American music, especially Brazilian music, through the slaves deported from there. But contemporary Angolan pop music is also heard in the other Portuguese-speaking countries. Kizomba and Kuduro are styles of music and dance that spread around the world from Angola. Conversely, an increasing influence from the US and Brazilian music markets can be felt in Luanda's modern musical life and youth culture.

The best-known pop musicians include Waldemar Bastos , Paulo Flores , Bonga , Vum Vum Kamusasadi , Maria de Lourdes Pereira dos Santos Van-Dúnem , Ana Maria Mascarenhas , Mario Gama , Pérola , Yola Semedo , Anselmo Ralph and Ariovalda Eulália Gabriel .

media

Angola was ranked 125th out of 180 countries in the 2017 Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders . Reporters Without Borders rated the press freedom situation in the country as "difficult".

TV

Televisão Pública de Angola (Angolan, state), TV Zimbo (Angolan, private), AngoTV (Angolan, private), Rádio Televisão Portuguesa (Portuguese, public), Rádio Televisão Portuguesa Internacional (Portuguese, public), Televisão Comercial de Angola (Angolan, state), ZON Multimédia (private), TV Record (Brazilian, private) TV Globo (Brazilian, private), Televisão de Moçambique (TVM) (Mozambican, state)

radio

RNA (Rádio Nacional de Angola) (state), Rádio LAC (Luanda Antena Comercial), Rádio Ecclesia (Catholic radio), Rádio Cinco (sports radio), Rádio Despertar (affiliated with UNITA), Rádio Mais (private), TSF (Portuguese radio ), Rádio Holanda (in Portuguese)

Internet

In 2016, 23.0% of the population used the internet.

newspapers

Jornal de Angola (state)

Weekly newspapers (all private): Semanário Angolense, O País , A Capital, Folha 8, Agora, Angolense, Actual, Independente, Cara, Novo Jornal, O Apostolado (ecclesiastical), Gazeta de Luanda

Economic weekly newspapers: Jornal de Economia & Finanças (state), Semanário Económico (private), Expansão (private)

magazines

Rumo (business magazine, private)

news agencies

Agência Angola Press (ANGOP; State)

Sports

- Soccer

On October 8, 2005, the Angolan national football team unexpectedly managed to qualify for the 2006 World Cup in Germany. A narrow 1-0 at group bottoms in Rwanda was enough to secure the ticket and eject Nigeria , who have featured at every World Cup since 1994, from the competition. It was the Angolan team's first appearance at a World Cup finals, where they were eliminated as third in their group after a 1-0 draw with Portugal, a 0-0 draw with Mexico and a 1-1 draw with Iran. Furthermore, the team took part in the African Championships (Africa Cup) in 1996 , 1998 , 2006 , 2008 , 2010 (as host), 2012 , 2013 and 2019 .

- basketball

The Angolan men's national basketball team has won eleven of the last thirteen editions of the Africa Cup of Nations, making it the most successful team in the history of the competition. Therefore, she regularly takes part in the World Cup and the Olympic Games . At the 1992 Games , Angola was the United States Dream Team 's first opponent . The greatest sporting successes so far have been surviving the preliminary rounds at the World Championships in 2002 , 2006 and 2010 .

- handball

The women's national handball team has already won the African championship eleven times and is also the first African team to reach the final round of a World Cup.

- roller hockey

This sport has been practiced in Angola since Portuguese colonial times. In March 2019, the first African Roller Hockey Championship was held in Luanda . Angola won the title after beating Mozambique .

- surfing

Surfing is becoming increasingly popular in Angola. Since 2013, the Social Surf Weekend has been held in Cabo Ledo every year in October with participants from home and abroad with the support of the Ministry of Tourism. In 2018, it became Angola's largest summer festival with over 4,000 participants. In September 2016, the country's first national surfing championship was also held in Cabo Ledo. It was organized by the Angolan Water Sports Federation. In July 2018 Angola became a member state of the International Surfing Association (ISA).

literature

- Patrick Alley: Angola's wealth is its undoing. In: Working Group Church Development Service (ed.): The overview. Volume 2, 1999. Leinfelden-Echterdingen, pp. 37–40.

- Association of Episcopal Conferences of the Central African Region ACERAC: The Church and Poverty in Central Africa: The Case of Oil. Malabo 2002.

- Anton Bösl: The parliamentary elections in Angola 2008. A country on the way to one-party democracy . KAS International Information 10/2008.

- Tom Burgis: The Curse of Wealth - Warlords, Corporations, Smugglers and the Plundering of Africa , Westend, Frankfurt 2016, ISBN 978-3-86489-148-9 .

- Jakkie Cilliers, Christian Dietrich (eds.): Angola's war economy. Pretoria 2000.

- Eugénio da Costa Almeida, Angola: Patência regional em emergência , Lisbon 2011.

- Michael Cromerford, The Peaceful Face of Angola: Biography of a Peace Process (1991 to 2002). Luanda 2005.

- Bettina blanket: A terra é nossa - Colonial society and liberation movement in Angola. Bonn 1981.

- Manuel Ennes Ferreira: A industry in the tempo of war: Angola 1975-1991. Lisbon 1999.

- Fernando Florêncio: No Reino da Toupeira. In the same (ed.): Vozes do Universo Rural: Reescrevendo o Estado em África. Lisbon.

- Global Witness: A Crude Awakening: The Role of the Oil and Banking Industries in Angola's Civil War and the Plunder of State Assets. London 1999.

- Global Witness: A rough trade: The Role of Companies and Governments in the Angolan Conflict. London 1998.

- Global Witness: Conflict Diamonds: Possibilities for the Identification, Certification and Control of Diamonds. London 2000.

- Global Witness: Os Homens dos Presidentes . London 2002.

- Jonuel Gonçalves: A economy ao longo da história de Angola. Luanda 2011.

- Rainer Grajek: Religion in Angola , In: Markus Porsche-Ludwig and Jürgen Bellers (eds.): Handbook of the Religions of the World , Bautz Verlag 2012

- Rainer Grajek: Angola , In: Markus Porsche-Ludwig, Wolfgang Gieler , Jürgen Bellers (eds.): Handbuch Sozialpolitiken der Welt , LIT Verlag 2013, pp. 82–87.

- Fernando Andresen Guimaraes: The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict. Houndsmills, New York 1998.

- Franz-Wilhelm Heimer : The decolonization conflict in Angola. Munich 1980.

- Franz Wilhelm Heimer : Social Change in Angola. Munich 1973.

- Tony Hodges: Angola from Afro-Stalinism to Petro-Diamond Capitalism. Bloomington, Indianapolis 2001.

- Tony Hodges, The Anatomy of an Oil State. Bloomington, Indianapolis 2004.

- Human Rights Watch: The Oil Diagnostic in Angola: An Update Complete Report. NYC 2001.

- International Monetary Fund: IMF Staff Country Report No. 99/25: Angola: Statistical Annex. Washington, D.C. 1999.

- International Monetary Fund: Mission Concluding Statements: Angola-2002 Article IV Consultation, Preliminary Conclusions of the IMF mission. Washington, D.C. 2002.

- Manfred Kuder, Wilhelm Möhlig (ed.): Angola. Munich 1994.

- Manfred Kuder: Crude Oil and Diamonds: Angola's Contested Export Goods. In: Geographical Review. Year 55, issue 7/8. Braunschweig 2003. pp. 36–38.

- Brank Lazitch: Angola 1974–1988: A Defeat of Communism. Meyers Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart 1989.

- Yves Loiseau, Pierre Guillaume Roux: Jonas Savimbi. Cologne 1989.

- Lukonde Luansi: Angola - The failure of the transition process. In: Wolf-Christian Paes, Heiko Krause (eds.): Between awakening and collapse - democratization in southern Africa. Bonn 2001. pp. 153–179.

- Jean-Michel Mabeko-Tali: Barbares et citoyens: L'identité national à l'épreuve des transitions africaines: Congo-Brazzaville, Angola. L'Harmattan, Paris 2005.

- Assis Malaquias: Rebels and Robbers: Violence in Post-Colonial Angola. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet , Uppsala 2007.

- Daniel Matcalfe: Blue Dahlia, Black Gold. A journey through Angola , Ostfildern, DuMont Reiseverlag, 2015, ISBN 978-3-7701-8274-9 .

- Médecins sans frontières: Angola uma população sacrificada. Brussels 2002.

- Christine Messiant: L'Angola post-colonial: Guerre et paix sans democratisation. Karthala, Paris 2008.

- Christine Messiant: L'Angola post-colonial: Sociologie politique d'une oleocratie. Karthala Paris 2009.

- Michel Offermann: Angola between the fronts. Centaurus, Pfaffenweiler 1988.

- Ricardo Soares de Oliveira: Magnificant and Beggar Land: Angola since the Civil War , Hurst, 2015.

- Wolf-Christian Paes: Rich Country, Poor Country: Oil Production and the War in Angola. In: Disloyal – Journal of Antimilitarism. No. 12. Berlin 2000. P. 8.

- Alfredo Pinto Escoval: Angola. In: Wolfgang Gieler (ed.): Handbook of foreign trade policies. Bonn 2004.

- Alfredo Pinto Escoval: State failure in southern Africa: The example of Angola. Berlin 2004.

- Hermann Pössinger: Agricultural development in Angola and Mozambique. Weltforum Verlag, Munich 1968.

- Manuel Alves da Rocha: Economy and Society in Angola. 2nd edition. Nzila, Luanda 2009, ISBN 972-33-0759-6 .

- Martin Schümer: Angola conflict. In: Dieter Nohlen (ed.): International relations, Piper's dictionary on politics. Volume 5. Munich 1984. pp. 44–46.

- Keith Somerville: Angola: Politics, Economics and Society. London 1986.

- Rui de Azevedo Teixeira, A Guerra de Angola 1961–1974 , Matosinhos: QuidNovi, 2010, ISBN 978-989-628-189-2 .

- Inge Tvedten: La scene angolaise. Limits and potential of the ONG. In: Lusotopie 2002/1. Paris 2002, pp. 171–188.

- Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on violations of Security Council sanctions against Unita. In: UN Security Council document S/2000/203. NYC 2000.

- UNITA-Renovada holds party congress. In: UN: The Angolan Mission Observer. February 1999. New York 1999.

- UNDP: A Descentralização de Angola. Luanda 2002.

- UNHCHR (ed.): Report on the question of the use of mercenaries as a means of violating human rights and impending the exercise of the right of peoples to self-determination, submitted by Mr. Enrique Ballesteros (Peru), Special Rapporteur pursuant to Commission resolution 1998/6 . Geneva 1995.

- UNICEF (ed.): Angola - Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 1996 . Luanda 1998.

- François Xavier Verschave: Dark Men, Black and White . In: The Overview . Volume 31 issue 2/95. Leinfelden-Echterdingen 1995, pp. 74–77.

- Nuno Vidal, Justino Pinto de Andrade (eds.): O processo de transição para o multipartidarismo em Angola , 3rd edition, Luanda 2008, ISBN 972-99270-4-9 .

- Nuno Vidal, Justino Pinto de Andrade (eds.): Sociedade civil e politica em Angola: Enquadramento regional e internacional , Luanda 2008, ISBN 978-972-99270-7-2 .

- Alex Vines: Planned Desolation of Angola . In: The Overview . Volume 30 issue 4/94. Leinfelden-Echterdingen 1994, pp. 99–101.

- Wilhelm Wess: Ten years ago the Cubans left Angola . In: German society for the African states of Portuguese language (ed.): DASP booklet Angola. DASP Series No. 96. Bonn 2001, p. 6.

- Elmar Windeler: Angola's bloody path to modernity: Portuguese ultra-colonialism and the Angolan decolonization process. trafo Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-89626-761-0 .

- Robert Zischg: The Soviet Union's policy towards Angola and Mozambique , Baden-Baden: Nomos, 1990, ISBN 978-3-7890-2019-3 .

web links

- CIA World Factbook: Angola

- Embassy of the Republic of Angola in Germany

- Country overview of Angola on the website of the Federal Foreign Office

- Database of literature on the social, political and economic situation in Angola

- Angola country profile on BBC News

- NationMaster – Angola (English)

- BTI 2018: Angola Country Report. In: bti-project.org (English).

- Markus Weimer, The Peace Dividend: Analysis of a Decade of Angolan Indicators, 2002-12. (PDF; 523 KB) In: chathamhouse.org . March 2012 (English).

Remarks

- ↑ In Angola itself, like most African languages, Portuguese pronunciation is [ aŋˈgɔːla ]

- ↑ Anti-colonial war 1961-1974, decolonization conflict 1974/75, civil war 1975-2002.

- ↑ See the article by Fernando Pacheco, a very good expert on the matter, in the Angolan newspaper Novo Jornal of May 15, 2015.