Wildebeest

| Wildebeest | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Blue wildebeest |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Connochaetes | ||||||||||||

| Lichtenstein , 1812 |

The wildebeest ( Connochaetes , the single animal the wildebeest, either bull or cow) are a genus of African antelopes that live in large herds and belong to the hartebeest group . Originally, only the white-tailed wildebeest and the blue wildebeest were distinguished as species within this genus . In the meantime, the Eastern white-bearded wildebeest, white-banded wildebeest and Serengeti-white-bearded wildebeest, previously classified as a subspecies of the blue wildebeest, have also been granted a species status.

At the beginning of the 21st century the population was around 1.5 million wildebeest. This makes wildebeest a key species . The most common species is the Serengeti white-bearded wildebeest with 1.3 million individuals, the main distribution of the genus is accordingly in the east of Africa. The rarest species is the eastern white-bearded wildebeest, which has between 6,000 and 8,000 animals.

features

The head and horns of the wildebeest have bovine-like characteristics. The horns are short, strong and present in both sexes. The head body length is about 2 m. Adult bulls of the blue wildebeest can reach a shoulder height of up to 156 cm, whereas the shoulder height of the adult male Serengeti wildebeest is between 110 and 134 cm. The smallest species is the white-tailed wildebeest, whose bulls reach a shoulder height of 110 to 120 centimeters. The cows have, on average, a slightly lower shoulder height than the bulls.

Bulls of the larger wildebeest species can reach a body weight of up to 250 kilograms, bulls of the white-tailed wildebeest as the smallest gnuart can reach a body weight of 180 kilograms. The body weight of the female of the blue wildebeest is between 190 and 215 kg, of the Serengeti white-bearded wildebeest, on the other hand, 140 to 180 kg and of the white-tailed wildebeest an average of 155 kg.

The color of the fur is different depending on the species. Blue wildebeest have a dark slate-gray fur with conspicuous horizontal stripes; the lightest species, on the other hand, is the Serengeti white-bearded wildebeest with a reddish-brown fur.

The sexual dimorphism in wildebeest is only slightly pronounced. This characteristic is observed in a number of African antelope species that live in a herd and often undertake long migrations. It is assumed that the small gender difference allows male animals to live in the herd without this leading to increased aggressiveness with other male animals in the herd. It enables male animals in particular to live under the protection of the herd.

Distribution area

| Wildebeest | |

|---|---|

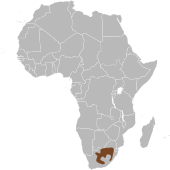

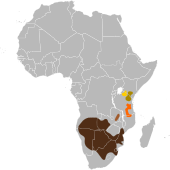

The distribution area of the wildebeest extends over the southeast and south of Africa. The northernmost distribution area is located just south of the equator in central Kenya and extends, apart from the Democratic Republic of the Congo , over all states of the subcontinent. The orange and the transition from the tree savannah to the moderate climate of the Highveld represent the southern limit of distribution. The white-tailed wildebeest living on the treeless plain of the Highveld is the wildebeest species with the southernmost distribution area. Despite this very large distribution area, the main occurrence is in the Serengeti . Around 85 percent of the world's wildebeest population now lives there, after the numbers in the other regions of the distribution area have declined sharply since the beginning of the 20th century.

The loss of habitat since the colonization of the African continent has led to the fact that in large parts of the range, instead of larger migrating herds, predominantly small, more sedentary populations are typical that live in protected areas. Loss of habitat is primarily due to the agricultural use of past pastures and the construction of extensive fences to prevent the transmission of animal diseases. In Etosha National Park , for example, up to 30,000 blue wildebeest lived in certain times of the year until the 1960s. Around 10,000 of the animals could be found in the region of the national park all year round. 20,000 wildebeest migrated from Ovamboland to the national park during the rainy season . After a fence interrupted this migration route, the wildebeest population in Etosha National Park declined to 2,000 to 3,000 individuals and has remained at this level since then. In Botswana, on government instigation, a protective fence was erected along the northern border of the Ghanzi District in the late 1980s , which was intended to improve the opportunities for domestic cattle farming in this region. It cut off large-scale access to watering holes for wild animals from the central area of the Kalahari and in 1988 led to the death of 50,000 wildebeest within four months.

Wildebeest were also introduced to regions outside of their historical range. Today they can also be found in the eastern highlands of Zimbabwe and in private game reserves in regions near the coast of Namibia.

habitat

Blue wildebeest, eastern white-bearded wildebeest, white-banded wildebeest and Serengeti-white-bearded wildebeest colonize the savannah regions with rainfall between 400 mm and 800 mm and occur accordingly in the thorn bush and dry savannah . They are types of plains and grazers with a preference for areas with short-growing vegetation and are most likely to be found in regions that are loosely covered with acacias . During the rainy season they can also be found in arid regions of their range, while during the dry season they gather in regions where high rainfall means that water points are permanently available. Wildebeest are rare above 1800 to 2100 meters, but during their seasonal migration they also cross grasslands in mountainous or hilly regions.

As the southernmost species, the white-tailed wildebeest originally colonized parts of South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho and was exterminated in Swaziland and Lesotho as early as the 19th century through heavy hunting. Originally it stayed in the grasslands of the climatically moderate highveld during the dry season and migrated to the arid Karoo in the rainy season . These migrations no longer take place today - it only occurs as a sedentary species in protected areas, but has now been resettled in Lesotho and Swaziland and successfully introduced into Namibia.

Way of life

hikes

Wildebeest are best known for their migration. However, not all herds migrate, as in many regions of the distribution area the urban sprawl and extensive fence systems that are supposed to protect domestic cattle herds prevent migration.

Not all herds of the Serengeti wildebeest living in the Serengeti migrate either; there are sedentary herds in the western corridor of the Serengeti National Park, in the Masai Mara and in the Ngorongoro Crater. The migration of the Serengeti white-bearded wildebeest, numerically the most numerous species within the genus, remains one of the most noticeable animal migrations in the world. During the rainy season , herds of this species of wildebeest can be found in the mineral-rich plains of the southeastern Serengeti in Tanzania . The rainy season ends in late May or early June and the grasses wither. The wildebeest then move north in a column across the Mara River into the Masai Mara plain in southern Kenya . There you will find isolated regions with strong grass growth due to showers. However, the grass here is severely deficient in phosphorus , so the wildebeest return to the Serengeti with the start of the rainy season towards the end of the year. During the necessary crossing of the Mara River, the wildebeest are expected by crocodiles , which prey hundreds of them.

Herd association

While herds of wildebeest of all ages and genders can be composed in arid habitats , males and females usually form separate herds. This is most pronounced during the time when the calves are born and numerous subgroups develop within the herd. Pregnant cows usually stay near other pregnant cows during this time and, once they have calved, join other cows that are leading lactating young. Non-pregnant females, on the other hand, are often found in herds of non-territorial males.

As with many other antelope species, dormant wildebeest lie in a star-shaped arrangement during the day, as they usually lie back to back when they lie down. As a result, the animals see in different directions and thus discover predators more quickly. At night they seek out the areas with the least trees and bushes and lay down there in linear formations that are no wider than about a dozen animals and the distance between the individual wildebeest is so great that other wildebeest can cross the formation. According to Richard D. Este, this is also an anti-predator strategy. In the event of an attack by, for example, spotted hyenas , every gnu can immediately flee without being hindered by another animal.

Reproduction

The gestation period of the wildebeest is about nine months. Then a single cub is born and suckled for a further nine months. The gender ratio is balanced at the time of birth: about as many male and female calves are born. From the point in time at which the calves separate from their mother animals, the gender ratio gradually shifts in favor of the females. In sedentary populations of the Serengeti white-bearded wildebeest, there is occasionally only one bull for every two females. Richard D. Estes attributes this to the fact that male animals in sedentary populations are exposed to higher stress, as they constantly fight for territory and bachelor groups tend to stay in the fringes of the herd, which offer poorer living conditions. The lifespan of the wildebeest is up to twenty years, but most of them are torn by predators long beforehand.

At around nine months of age, the calves leave their mother animals and form yearling groups regardless of gender. However, some of the female yearlings and a small number of male yearlings remain in the cow herds and still follow their respective mothers. In their second year of life, these young animals form increasingly separate groups according to the sexes. From the beginning of the third year of life, females can hardly be distinguished externally from non-pregnant older cows. With the Serengeti white-bearded wildebeest, around 80 percent of these female young are mated during the next rut, when they are around 28 months old.

cops

Young bulls join separate bachelor associations from the age of two. These are mixed in terms of age, but the young bulls can still be externally distinguished from the older ones in their third year of life, as their horns are less powerful and their physique is slimmer. Young bulls complete their physical development at the age of four or five. Compared to the bachelor associations of closely related antelope species such as the North African hartebeest , the lyre antelope and the Grant's gazelle , in which the bulls often fight each other, the members of such a wildebeest bachelor association are comparatively less aggressive towards one another. Richard D. Estes attributes this, among other things, to the fact that the distance between territorial bulls is smaller than that of these species and that male wildebeest are therefore generally more tolerant towards other members of their sexes.

Bulls try to establish a territory because only such a territory gives them a chance to reproduce. This territory is defended against other males; Such encounters result in ritualized threatening gestures and fights with the horns. If a herd of females enters such an area of their own, the male takes control of them, defends them and mates with them until they leave the territory again. In regions with a low population of white tailed wildebeest, the bulls are about a kilometer apart. In contrast, the minimum distance between the territories in regions with a high population of white-tailed wildebeest is around 180 meters. The areas of the Serengeti white-bearded wildebeest are much smaller: in the Ngorongoro crater, between 57 and 85 territorial bulls were counted per square kilometer.

Relationship with other animal species

The predators of the wildebeest include lions, leopards, hyenas and the African wild dog as well as crocodiles. Healthy, fully grown wildebeest have considerable physical strength and can therefore cause serious injuries to attackers. As a rule, it is young animals and sick wildebeest that are hit by predators. However, flight is the typical behavior of attacking predators. Fleeing wildebeests can reach speeds of up to 80 km / h.

Migrating herds are accompanied by vultures, for which the carcasses of wildebeest are an essential source of food. About 70 percent of the wildebeest carcasses are eaten by vultures. The decline in the number of migrating wildebeest also had a negative effect on the vulture population.

In the open savannah, herds of zebras and wildebeest mix and are also socialized during the migrations. Often it is herds of zebra that precede the herds of wildebeest. There is a certain ecological dependency, since zebras eat the high, nutrient-poor grass stands, while the wildebeest eat the middle and nutrient-rich ones. This socialization also reduces the risk that predators can sneak up on them. Wildebeest also respond to alarm calls from other animal species. For example, wildebeests react to alarm calls from baboons and are able to distinguish them very precisely from other, similar-sounding calls.

Systematics

|

Internal systematics of the Alcelaphini according to Steiner et al. 2014

|

The wildebeest form a genus from the family of horned bearers (Bovidae). Within the horn-bearers they are placed in the subfamily of the Antilopinae and the tribe of the hartebeest (Alcelaphini). The closest relatives of the wildebeest are the red hartebeest ( Alcelaphus ), the lyre antelopes ( Damaliscus ) and the hunter antelope ( Beatragus ). In general, red hartebeests are characterized by their large body with a characteristically high position of the shoulder and sloping back, the transversely ribbed horns and the deep glandular pits in the face. Further features can be found in the long skull and the large cavities in the forehead that extend into the beginnings of the horns. According to molecular genetic studies, the wildebeest form the sister group to all other hartebeest, they separated from the other lines as early as the Upper Miocene .

Originally, only the white-tailed wildebeest and the blue wildebeest were distinguished as species within this genus . During a revision of the horned bearers presented by Colin Peter Groves and Peter Grubb in 2011, some forms that were originally considered to be subspecies of the blue wildebeest were raised to species status. The following species are recognized today:

- White-bearded wildebeest or Eastern white-bearded wildebeest ( Connochaetes albojubatus Thomas , 1892)

- White-tailed wildebeest ( Connochaetes gnou ( Zimmermann , 1780))

- White -banded Gnu or Nyassa Gnu ( Connochaetes johnstoni Sclater , 1896)

- Serengeti white-bearded wildebeest or western white -bearded wildebeest ( Connochaetes mearnsi ( Heller , 1913))

- Streifengnu ( connochaetes taurinus ( Burchell , 1824))

The first scientific description of the genus Connochaetes was made by Martin Lichtenstein in 1812. In his publication, Lichtenstein tried to structure the antelopes and presented Connochaetes as a long-tailed form with mane and bags under the eyes, with both sexes wearing horns.

Humans and wildebeest

Wildebeest have always been hunted for their meat and skin; Fly whiskers were customarily made from the tails. With the arrival of white settlers, the animals were shot down en masse, so that the herds became continuously smaller. In particular, the stocks of the white-tailed wildebeest declined so early that the way of life and especially the migratory movements of this wildebeest species were never studied in the wild. It survived thanks to the initiative of some farmers who protected the animals on their land.

In the Serengeti National Park, the Serengeti white-bearded wildebeest there have multiplied again thanks to massive conservation efforts. From 500,000 animals in 1970, the population rose again to around 1.3 million. However, not all of Africa is doing so well for the wildebeest. Stocks continue to decline in many countries, including southern Africa, where the blue wildebeest stock dropped from 300,000 in 1970 to 130,000. The population of the white-banded gnu could be around 70,000 to 80,000, while the white-bearded gnu may only comprise around 8,000 individuals.

The name Gnu is taken from the Khoikhoi language .

Video

- Africa - The Serengeti IMAX ( DVD ) (The film focuses on the wildebeest migration)

- Serengeti . Documentary by Reinhard Radke . Germany 2011.

literature

- Richard D. Estes: Genus Connochaetes Wildebeest. In: Jonathan Kingdon, David Happold, Michael Hoffmann, Thomas Butynski, Meredith Happold and Jan Kalina (eds.): Mammals of Africa Volume VI. Pigs, Hippopotamuses, Chevrotain, Giraffes, Deer and Bovids. Bloomsbury, London, 2013, pp. 527-546

- Richard D. Estes: The Gnu's World: Serengeti Wildebeest Ecology and Life History. University of California Press, Berkeley 2014, ISBN 978-0-520-27319-1 .

- Colin P. Groves and David M. Leslie Jr .: Family Bovidae (Hollwow-horned Ruminants). In: Don E. Wilson, Russell A. Mittermeier (eds.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 2: Hooved Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2011, ISBN 978-84-96553-77-4 , pp. 444-779 (pp. 707-709)

- Ronald M. Nowak: Walker's Mammals of the World . 6th edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1999, ISBN 0-8018-5789-9 (English).

- Robyn Stewart: Serengeti Wonder World. Moewig, 2004, ISBN 3-8118-1902-X

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Colin P. Groves and David M. Leslie Jr .: Family Bovidae (Hollwow-horned Ruminants). In: Don E. Wilson, Russell A. Mittermeier (eds.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 2: Hooved Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2011, ISBN 978-84-96553-77-4 , pp. 444–779 (pp. 458–460 and pp. 707–709)

- ^ A b Colin Groves and Peter Grubb: Ungulate Taxonomy. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011, pp. 1-317 (pp. 208-218)

- ↑ Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 101.

- ↑ a b Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 85.

- ↑ Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 86.

- ↑ Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 87.

- ↑ Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 40.

- ↑ a b c d e Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 59.

- ↑ a b c Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 78.

- ↑ Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 99.

- ↑ Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 91.

- ↑ Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 102.

- ↑ a b c Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 148.

- ↑ a b c d Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 145.

- ↑ a b Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 161.

- ↑ Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 146.

- ↑ Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 163.

- ↑ Estes: The Gnu's World . P. 168.

- ↑ PBS: Animal Guide: Blue Wildebeest. In: Nature. Retrieved January 8, 2013 .

- ↑ Christopher McGowan: A Practical Guide to Vertebrate Mechanics . Cambridge University Press, February 28, 1999, ISBN 9780521576734 , p. 162.

- ↑ Munir Z. Virani: Major Declines in the Abundance of Vultures scavenging and Other Raptors in and around the Masai Mara ecosystem, Kenya. In: Biological Conservation 144 (2), 2011, pp. 746-752. doi : 10.1016 / j.biocon.2010.10.024 .

- ↑ J. Tyler Faith, Jonah N. Choiniere, Christian A. Tryon, Daniel J. Peppe and David L. Fox: Taxonomic status and paleoecology of Rusingoryx atopocranion (Mammalia, Artiodactyla), an extinct Pleistocene bovid from Rusinga Island, Kenya. In: Quaternary Research 75, 2011, pp. 697-707

- ↑ Dawn M. Kitchen: Comparing Responses of Four Ungulate Species to Playbacks of Baboon Alarm Calls. In: Animal Cognition 13 (6), 2010, pp. 861-870. doi : 10.1007 / s10071-010-0334-9 . PMID 20607576 .

- ↑ a b Cynthia C. Steiner, Suellen J. Charter, Marlys L. Houck and Oliver A. Ryder: Molecular Phylogeny and Chromosomal Evolution of Alcelaphini (Antilopinae). In: Journal of Heredity 105 (3), 2014, pp. 324–333 doi: 10.1093 / jhered / esu004

- ↑ Martin Lichtenstein: The genus antelope. Magazine for the latest discoveries in the entire natural history 6, 1812, pp. 147–160 ( [1] )

- ↑ Richard D. Estes: Genus Connochaetes Wildebeest. In: Jonathan Kingdon, David Happold, Michael Hoffmann, Thomas Butynski, Meredith Happold and Jan Kalina (eds.): Mammals of Africa Volume VI. Pigs, Hippopotamuses, Chevrotain, Giraffes, Deer and Bovids. Bloomsbury, London, 2013, pp. 527-546